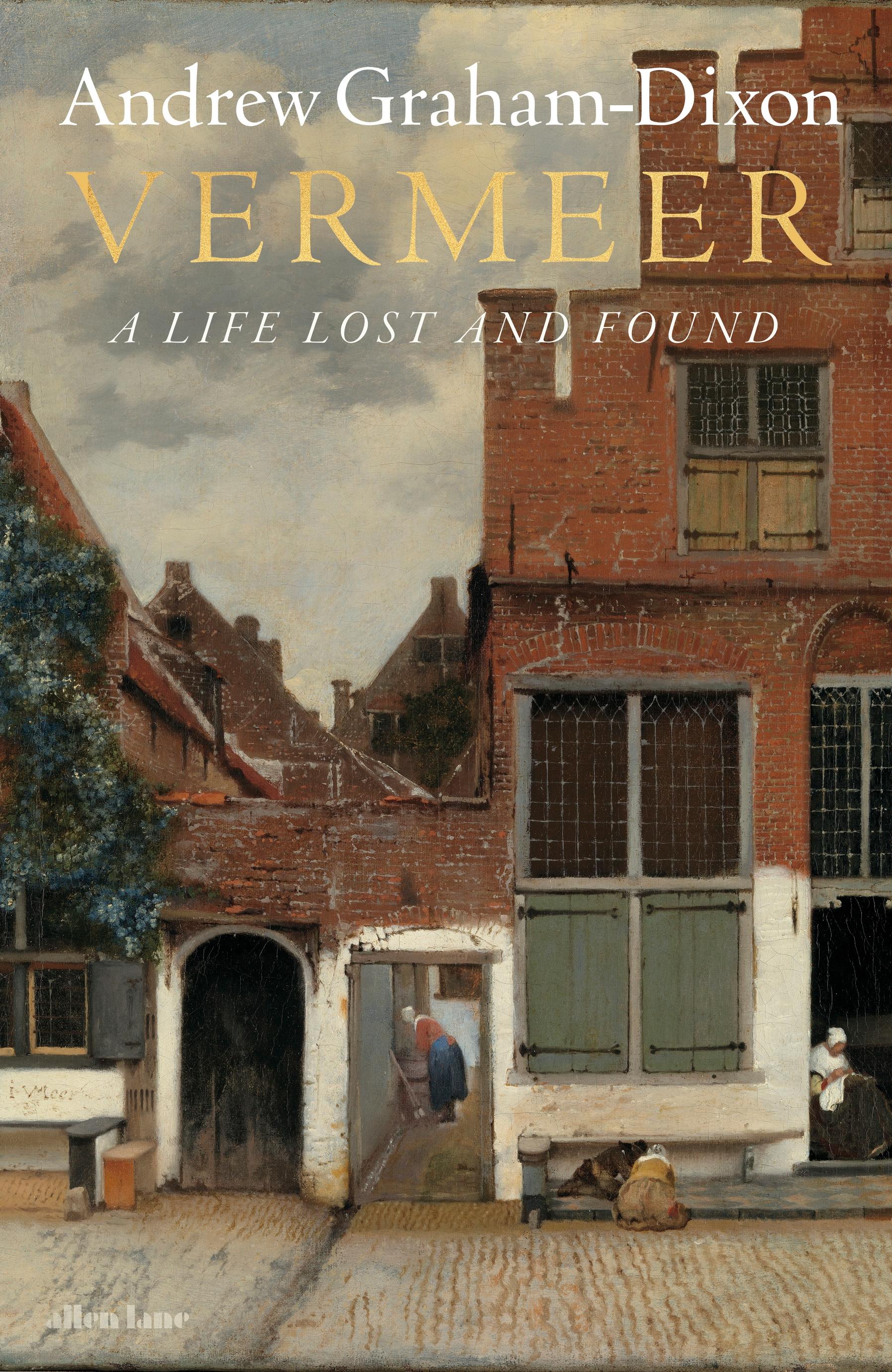

Vermeer

Andrew Graham- Dixon Vermeer

A Life Lost and Found

ALLEN LANE an imprint of

ALLEN LANE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Allen Lane is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published 2025 001

Copyright © Andrew Graham-Dixon, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Set in 10.5/14pt Sabon LT Std Typeset by Six Red Marbles UK , Thetford, Norfolk Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978–1–846–14710–4

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

To my kind and brave father, Anthony. You once said I was an advocate, like you. I hope this book proves you right.

Hatred is increased by being reciprocated, and can on the other hand be destroyed by love.

Baruch Spinoza, Ethics

List of Illustrations

Family

Part One: The Inheritance, 1560–1632

Part Two: Childhood, Education, Marriage, 1632–57 79

Part Three: The Invisible Church, 1657–72

Part Four: Disaster, Death, Legacy, 1672–5

List of Illustrations

All paintings are by Johannes Vermeer, unless otherwise stated. Images of the works are reproduced by kind permission of the current owners or custodians, unless otherwise noted in italics.

Endpapers

Front: Abraham Goos, Comitatus Hollandia, 1630. Hand-coloured engraved map of Holland, published by Claes Jansz Visscher. Universitätsbibliothek, Bern.

Rear: Joan Blaeu, Delfi Batavorum vernacule Delft, 1649. Handcoloured engraved plan of the city of Delft. Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Colour Plates

1. Diana and her Companions, c. 1653. Oil on canvas. 98.5 x 105 cm. Mauritshuis, The Hague.

2. The Procuress, 1656. Oil on canvas. 143 x 130 cm. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden. Photo: Bridgeman Images.

3. Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, c. 1654. Oil on canvas. 160 x 142 cm. National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh. Photo: © National Galleries of Scotland / Bridgeman Images

4. Andrea Vaccaro, The Death of St Joseph, c. 1645–50. Oil on canvas. 211.5 cm x 158 cm. Museo di Capodimonte, Naples. Photo: Scala, Florence, courtesy of the Ministero Beni e Att. Culturali e del Turismo.

5. St Praxedis, 1655. Oil on canvas. 101.6 x 82.6 cm. Kufu Company Inc., on long-term loan to the National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo. Photo: Christie’s/Bridgeman Images.

6. Felice Ficherelli, St Praxedis, c. 1645–50. Oil on canvas. 115cm x 90 cm. Private collection. Photo: Piemags/Alamy.

7. Officer with a Laughing Girl, c. 1658. Oil on canvas. 50.5 x 46 cm. The Frick Collection, New York. Henry Clay Frick Bequest. Photo: © The Frick Collection

8. A Maid Asleep, c. 1658. Oil on canvas. 87.6 x 76.5 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Bequest of Benjamin Altman, 1913.

9. Gerard ter Borch, Self-portrait, 1668. Oil on canvas, 62.7 x 43.7 cm. Mauritshuis, The Hague.

10. Gerard ter Borch, Man on Horseback, c. 1634–5. Oil on panel. 54.9 x 41 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Juliana Cheney Edwards Collection. Photo: © 2025 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All rights reserved / Bridgeman Images.

11. Caspar Luyken, The Explosion of the Gunpowder Tower in Delft in 1654, 1698. Etching published by Pieter van der Aa, Leiden. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

12. Egbert van der Poel, A View of Delft after the Explosion, 1654. Oil on wood. 36.2 × 49.5 cm. The National Gallery, London. Bequeathed by John Henderson, 1879. Photo: © The National Gallery, London.

13. Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem, The Massacre of the Innocents, 1590. Central panel of a triptych. Oil on canvas, 268 × 257 cm. Frans Halsmuseum, Haarlem. Photo: © NPL – DeA Picture Library / M. Carrieri / Bridgeman Images.

14. Gerard ter Borch, The Ratification of the Treaty of Münster, 1648. Oil on copper. 45.4 x 58.5 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, on loan from the National Gallery, London. Presented by Sir Richard Wallace, 1871. Photo: Rijksmuseum.

15. Willem Duyster, The Marauders, c. 1635. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Oil on wood. 37 x 50 cm. Photo: RMN-Grand Palais / Adrien Didierjean / Dist. Foto SCALA, Florence.

16. Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, c. 1656–7 (pre-restoration). Oil on canvas. 83 x 64.5 cm. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden. © Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden / Bridgeman Images.

xii

17. Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, c. 1656–7 (postrestoration). Oil on canvas. 83 x 64.5 cm. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden. © Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden / Bridgeman Images.

18. Woman in Blue Reading a Letter, c. 1664. Oil on canvas. 46.5 x 39 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

19. The Glass of Wine, c. 1659–60. Oil on canvas. 65 x 77 cm. Staatliche Museen Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. Photo: Scala, Florence / bpk, Bildagentur für Kunst, Kultur und Geschichte, Berlin.

20. Young Woman with a Wine Glass, c. 1659–60. Oil on canvas. 67 x 78 cm. Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, Brauschweig. Photo: Scala, Florence / bpk, Bildagentur für Kunst, Kultur und Geschichte, Berlin

21. The Music Lesson, c. 1661–2. Oil on canvas. 73.3 x 64.5 cm. The Royal Collection Trust. © His Majesty King Charles III , 2025. Photo: Bridgeman Images

22. The Concert, c. 1661–2. Oil on canvas. 72.5 x 64.7 cm. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, MA . Stolen in 1990. Photo: Photo © Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum / Bridgeman Images.

23. Cornelius Boel, Inconcvssa Fide (Unshakeable Faith). Illustration from Otto van Veen, Amorum Emblemata, Antwerp, 1608, p. 55.

24. Dirck van Baburen, The Procuress, 1622. Oil on canvas. 101.6 x 107.6 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA . M. Theresa B. Hopkins Fund. Photo: © 2025 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All rights reserved/Bridgeman Images.

25. Gerard ter Borch, An Officer Writing a Letter, with a Trumpeter, c. 1658. Oil on canvas. 56.8 × 43.8 cm. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA . The William L. Elkins Collection, 1924.

26. Gerard Houckgeest, Interior of the Oude Kerk in Delft, 1654. Oil on panel. 48.7 x 40.2 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

27. Young Woman with a Water Pitcher, c. 1662. Oil on canvas. 45.7 x 40.6 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Marquand Collection, Gift of Henry G. Marquand, 1889.

28. The Milkmaid, c. 1659. Oil on canvas. 45.5 x 41 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

29. Woman with a Balance, c. 1659. Oil on canvas. 42.5 x 38 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC . Widener Collection.

xiii

list of illustrations

30. A Lady Writing, c. 1665–7. Oil on canvas. 45 x 39.9 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC . Gift of Harry Waldron Havemeyer and Horace Havemeyer, Jr., in memory of their father, Horace Havemeyer.

31. Woman with a Pearl Necklace, c. 1665–7. Oil on canvas. 55 x 45 cm. Staatliche Museen Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. Photo: Scala, Florence / bpk, Bildagentur für Kunst, Kultur und Geschichte, Berlin.

32. Girl with a Pearl Earring, c. 1667–8. Oil on canvas. 46.5 x 40 cm. Mauritshuis, The Hague.

33. Study of a Young Woman, c. 1667–8. Oil on canvas. 44.5 x 40 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of Mr and Mrs Charles Wrightsman, in memory of Theodore Rousseau Jr, 1979.

34. Girl with a Red Hat, c. 1668. Oil on panel. 23.2 x 18.1 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC . Andrew W. Mellon Collection.

35. The Lacemaker, c. 1670–71. Oil on canvas (attached to panel). 24.5 x 21 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Photo: RMN-Grand Palais /Dist. Photo SCALA, Florence

36. The Guitar Player, c. 1670. Oil on canvas. 53 x 46.3 cm. Kenwood House. English Heritage, Trustees of the Iveagh Bequest, London. Photo: © Historic England/Bridgeman Images.

37. A Young Woman Standing at a Virginal, c. 1670. Oil on canvas. 51.7 × 45.2 cm. The National Gallery, London. Photo: © The National Gallery, London.

38. The Love Letter, c. 1672–5. Oil on canvas. 44 x 38.5 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

39. Mistress and Maid, c. 1668. Oil on canvas. 90.2 x 78.7 cm. Frick Collection, New York. Henry Clay Frick Bequest.

40. View of Delft, c. 1665. Oil on canvas. 98.5 x 117.5 cm. Mauritshuis, The Hague.

41. The Little Street, c. 1660. Oil on canvas. 54.3 x 44 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

42. Modern photograph of the site of the house/hidden church, Delft. Photo: Edwin Raap/Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed.

43. Modern photograph of the hidden Remonstrant church, Delft. Photo: © Andrew Graham-Dixon.

xiv

44. The Little Street (detail), c. 1660. As above.

45. Godfried Schalcken, Pieter Teding van Berkhout, 1674. Oil on copper. 13.3 x 11.1 cm. Private collection. Photo: RKD/ Netherlands Institute for Art History

46. Godfried Schalcken, Elisabeth Ruysch, 1675. Oil on copper. 13.3 x 11.1 cm. Private collection. Photo: RKD/Netherlands Institute for Art History

47. Pieter van der Werff, Adrian Paets, 1668. Oil on canvas. 82 x 68 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

48. Anon. (Dutch or German school), Baruch Spinoza, c. 1675–1750. Oil on canvas. 74.0 × 59.8 cm. Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel.

49. The Astronomer, 1668. Oil on canvas. 50 x 45 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Photo: RMN-Grand Palais / Franck Raux/ Dist. Photo SCALA, Florence.

50. The Geographer, 1669. Oil on canvas. 51.6 x 45.4 cm. Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main.

51. Allegory of the Catholic Faith, c. 1670–72. Oil on canvas. 114.3 x 88.9 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931.

52. The Art of Painting, c. 1670–72. Oil on canvas. 120 x 100 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Photo: Bridgeman Images.

53. Lady Writing a Letter with Her Maid, c. 1672–5. Oil on canvas. 72.2 x 59.5 cm. National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin. Presented by Sir Alfred and Lady Beit, 1987. Photo: Bridgeman Images.

54. Woman with a Lute, c. 1662–5. Oil on canvas. 51.4 x 45.7 cm. Metropolitan Museum, New York. Bequest of Collis P. Huntington, 1900 (25.110.24).

55. Young Woman Seated at a Virginal, c. 1675. Oil on canvas. 51.5 × 45.5 cm. The National Gallery, London. Salting Bequest, 1910. © The National Gallery, London

Black and White Illustrations

p. 24. Jan Luyken, The Cruel Massacre of Naarden by the Spanish in 1572, 1679. Etching. Amsterdam Museum, Amsterdam. p. 26. Anon., Executions of Haarlem Residents by the Spanish on the

xv

Grote Markt in front of the Town Hall in Haarlem after the Surrender of the City on 13 July 1573, 1782–4. Etching. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

p. 29. Frans Hogenberg, The ‘Spanish Fury’ in Antwerp: Atrocities of the Spanish Soldiers on 5 November 1576, 1576–8. Etching. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

p. 40. Anon., Jacobus Arminius, 1650–74. Engraving. Museum Catharijneconvent, Utrecht.

p. 50. Anon., The Beheading of Oldenbarnevelt in The Hague on 13 May 1619, 1619. Engraving. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

p. 65. Anon. (Northern Netherlandish school), after François Schillemans, The Opening of the National Synod in Dordrecht on 13 November 1618, 1618–19. Engraving. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

p. 72. Salomon Savery after Casper Casteleyn, Camphuysen Surrounded by Allegorical Personifications of Faith, Hope and Love, 1635–65. Engraving. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

p. 89. Gerrits Lambert, The Guild of St Luke on the Voldersgracht seen from the Oude Manhuissteeg, 1820. Drawing. Delft City Archives.

p. 97. Anon. (Northern Netherlandish school), The Siege of Sas-vanGent by Frederik Hendrik in 1644, 1662–4. Etching. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

p. 103. Jacques Callot, La Pendaison (The Hanging), plate 11 from Les Misères et les Malheurs de la Guerre (The Miseries and Misfortunes of War), 1633. Etching; first or second state of three. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Bequest of Edwin De T. Bechtel, 1957.

p. 111. Romeyn de Hooghe, after Johannes de Vouw, A View of the Statue of Erasmus on the Grotemarkt in Rotterdam, 1694–5. Etching with engraving. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

p. 115. Detail of a register with the names of Johannes Vermeer, Pieter de Hooch and Carel Fabritius, from Twee Meesterboeken van het St Lucasgilde te Delft (The Book of Masters of St Luke’s Guild), 1613–1715. Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Nationale bibliotheek van Nederland, The Hague, KW 75 C 6, part 2, p.3r.

p. 154. Frans van Mieris the Elder, The Charlatan (detail), c. 1653–5. Oil on panel. 45 x 36 cm. Galeria della Uffizi, Florence. Photo:

xvi list of illustrations

Scala, Florence – courtesy of the Ministero Beni e Att. Culturali e del Turismo.

p. 175. Egbert van Heemskerck, L’Assemblée des Couacres (The Quaker Assembly), c. 1680. Engraving. Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Estampes et photographie, Paris (RESERVE QB -201 (76)-FOL ). Photo: BnF.

p. 180. Pierre Tanjé after Louis Fabritius Dubourg, Lord’s Supper in a Collegiant Church in Rijnsburg, c. 1735. Illustration from J. F. Bernard, Ceremonies et Coutumes Religieuses de Tous les Peuples du Monde, Amsterdam, 1736. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

p. 187 Rembrandt (Rembrandt van Rijn), Cornelis Claesz Anslo, 1641. Etching; second of five states. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of Felix M. Warburg and his family, 1941 (41.1.51)

p. 196. Balthasar Bernards, after Louis Fabricius Dubourg, A Baptism at the ‘Grote Huis’, Rijnsburg, 1736. Etching with engraving and drypoint. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

p. 244. Abraham Rademaker, Interior of Remonstrant Church, Delft, c. 1700. Drawing. Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands.

p. 302. Coenraet Decker, View of the Muiderslot and the city of Muiden, 1660–85. Etching. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

p. 305. Anon. (German School) after Romeyn de Hooghe, The Shameful Execution of the de Witt Brothers, 1672–99. Etching with engraving. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

p. 308. Romeyn de Hooghe, illustration of French atrocities against Dutch villagers, from Abraham de Wicquefort, Advis fidelle aux veritables Hollandois, 1673. Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Nationale bibliotheek van Nederland, The Hague.

p. 329. Act of Ownership for 106 Oude Delft, with Pieter Claesz van Ruijven’s signature: Gemeentearchief, Delft, akte 2268, folio 923r1 (waarbrief 0i001). The document is undated.

p. 331. Matthijs Pool, A trekschuit at the Inn and Peacock Garden on the Nieuweramstel, 1700–1725. Etching. Noord-hollands Archief, Haarlem.

xvii

The United Provinces, 1648–72

NORTH SEA

UTRECHT

Rotterdam

ZEELAND

Flushing

Aalst

Antwerp

NORTH BRABANT

GELDERLAND

GRONINGEN

Deventer

Valenciennes

Jemmingen

River Maas

River Scheldt

River Rhine

Marburg

advance of the French army Dutch ‘Ring of Fortresses’ 0 50 100 mi 0 75 150 km

Louis XIV’s invasion of the Dutch Republic, 1672

Sas van Ghent

THE ZUIDERZEE

DUTCH REPUBLIC

River Scheldt

SPANISH NETHERLANDS

River Maas

BISHOPRIC OF LIÈGE

SPANISH NETHERLANDS FRANCE

BISHOPRIC OF MUNSTER

DUCHY OF CLEVES

River Rhine

OTHER GERMAN PRINCIPALITIES

Schenkenschans

Journey undertaken by William Crowne, 1636

The Hague

Delft

Emmerich Arnhem

Wesel

Frankfurt

Mainz

Bacharach

HESSE

Pfalz Castle

Rudeshein

River Rhine

Family Trees

The Family of Johannes Vermeer

Beatrix Gerrits = = 2) Balthasar Gerrits 1) = = (?) Beatrix van Buy Vouck ca. 1585 = ca. 1656 ca. 1573 = ca. 1630 1596?

Tanneken Balthus (?)

Reynier Baltens ca. 1600–1653

1) = = Susanna Heyndrixdr. d. 1634

2) = = Macyken Gijsberts d. after 1654

1615

Digna Baltens ca. 1595–1670

Reynier Jansz. Vos (alias Vermeer) ca. 1591–1652 = = 1670 1647

Abigail van Brussel 2) Anthony Gerritsz. van der Wiel ca. 1620–1693 = = 1) = =

Gertruy Vermeer 1620–1670

1674

Johannes Cramer Maria Vermeer ca. 1654–d. after 1713

Elisabeth Vermeer ca. 1657–before 1713

Cornelia Vermeer (?)

Note: This chart omits the children of Vermeer’s uncles and aunts. Aleydis Vermeer d. 1749 Beatrix Vermeer

Elisabeth = = = =

Johan Christophorus Hopperus Catharina Hopperus

Corstiaen ca. 1515–1566

Annitgen Goverts = =

1597

Jan Reyersz d. 1597 = = 2) = =

Anthony Jansz Vermeer d. bef. 1629

1) Neeltge Goris ca. 1567–1627

Claes Corstiaensz d. 1618

Adriaentge Claes van der Minne ca. 1599–1672

3) = =

Johannes Vermeer 1632–1675

Johannes Vermeer b. ca. 1664-1665

Johannes

Tryntje Isbrantsdr.

Ariaentge Dircksdr. van der Zeijl 1) = =

Jan Thonisz. Back d. 1632 = =

Jan Michielsz. van der Beck d. 1621 1620

Heymen van der Hoeve

Dirck Claesz. van der Beck 1582–1657

Trinjntge Cornelis = =

Maertge Jans ca. 1594–1661

Catharina Bolnes ca. 1631–1688 = = 1653

Maria Anna Frank = = = = =

Gertruyd Vermeer d. aft. 1713

Antonius Vermeer 1689– aft. 1713

Jan Heymensz van der Hoeve ca. 1588–1660

Franciscus Vermeer ca. 1666–aft. 1708

Maria de Wee = =

Gysbrecht van der Hoeve d. 1651 Heymen van der Hoeve

Catharina Vermeer d. aft. 1713

Ignatius Vermeer 1672–d. aft. 1713 a child 1674–1678

The Family of Catharina Bolnes

Geen Symonsz Alidt Gerritsdr = =

Adriaen Huygensz Cool

Maria Geenen ca. 1528–1558 = =

Elisabeth Geenen b. ca. 1520

Jan Willemsz Thin ca. 1502–1570 = =

Erckenraad Duyst van Voorhoudt

Adriaen Adriaensz Cool d. 1604 = =

Aeltgens Thins

Clementia van Schonenburch

1603

Cunera Splinters d. 1644

Jan Greensz Thins ca. 1580–1647 1) = =

Geen (Gheno) Jansz Thins

1645

Susanna van de Bogaert 2) = = = = = = 1) Willem Vrynes = = 2) Johan Vermeul

Clementia Thins Lucia Thins Jacob van Rosendael

Aleydis Magdalena van Rosendael d. aft. 1703 = = 1575

Cornelia Clementia van Rosendael d. 1700

Cornelia Thins ca. 1587–1661

Dirck Cornelisz van Hensbeeck ca. 1502–1569

Aechte Hendricksdr ca. 1508–1559 = =

Neltgen Gysbertsdr Hendrick Dircksz van Hensbeeck ca. 1528–1571 = =

1) = =

Catharina Hendricksdr van Hensbeeck d. 1633

2) = =

Gerrit Gerritsz d. 1627 1605

Willem Jansz Thin ca. 1554–1601 1584 = =

Jan Willemsz Thins ca. 1596–1651

Maria Thins ca. 1593–1680 1622 = =

Reynier Bolnes d. 1674

Elizabeth Thins ca. 1599–1640

Willem

Diewertje Hendricksdr van Hensbeeck d. 1604

Maria Gerrits Camerling b. ca. 1609 1637 = =

Jan Hendricksz van der Wiel ca. 1602–1671

Willem Cle us

Adriana Camerling Catharina Camerling

Lambert Cle us

Neltge Jansdr

Cornelius Pouwelsz Bolnes = =

Pouwels Bolnes b. ca. 1589

Cornelia Neeltge Bolnes

Claes Cornelisz van Hensbeeck

Jan Bolnes

Johannes Vermeer 1632–1675 = =

Catharina Bolnes ca. 1631–1688

Cornelia Bolnes d. 1643

Willem Bolnes d. 1676

The Family of Pieter Claesz van Ruijven

Pieter Jansz van Ruijven

Martgen Dircxsdr van Santen = =

Niclaes Pietersz van Ruijven Maria Graswinckel = =

Cornelis Jansz Graswinckel Sara Mennincx = =

Simon Vincentens de Knuijt

Magdeleentje Willemsdr van der Mersche (1595–1654) = =

Pieter Claesz van Ruijven ca. 1624–1674 Maria Simonsdr de Knuijt (d. 1681) = =

Vincent Maria de Knuijt

Machteld Jans de Leutering = =

Vincent Vermeer’s main patrons

Magdalena Pieters van Ruijven (1655–1682)

Maria (b. 1657)

Simon (b. 1662)

Jacob Dissius = =

Both Magdalena’s siblings were baptized but neither survived infancy.

Maddalena (baptized 17 March 1654)

The Family of Adrian Paets

Claes Paets (1558–1622)

LEIDEN ROTTERDAM

Vincent Claesz Paets (1590–16??)

Cunera Geertgen = =

Willemijnte Harms van der Vult

Aechte van Bakensese

Adrian Paets

Maria de Lange (1635–1675) – 4 children = Elizabeth van Berckel (1638–1682) – 4 children = Françoise de Groot =

LEIDEN

Adrian Claesz Paets (1585–1644)

Lysbeth (Elisabeth) van Stoopenburch Maertensdr = =

Nicolaes Paets (1615–1680)

Elysabeth Paets = =

The Paets van Santhorst cousins, and the Van Berkhouts

Jacob Cornelisz Paedts (Paets van Santhorst) (1560–1622)

LEIDEN

Willem Paets (1596–1669) Mayor of Leiden

Maria Heerman = =

DORDRECHT

Paulus Teding van Berkhout = =

Jacomina Teding van Berkhout-van der Vorst

Nicolaes Coenraezs Ruysch Mayor of Dordrecht = =

Pieter Paulusz Teding van Berkhout (1643–1733) = =

Maria Willemsdr Paets (1621–1670)

Elisabeth Nicholaesdr Ruysch (1646–1669)

Preface and Acknowledgements

The origins of this book lie in two conversations that took place a long time ago, and a decade apart. In early 1990 I had lunch with Lawrence Gowing, who was kind enough during his later years to show an interest in a young art critic with much to learn. On that particular day he was filled with enthusiasm for a new book that he had just read and reviewed: Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History, by the economist and art historian John Michael Montias. He told me that it contained a remarkable trove of newly discovered archival information about the enigmatic Johannes Vermeer, a painter close to his heart. Lawrence described Montias’s book as a kind of Pandora’s box, containing numerous revelations and promising yet more to anyone prepared to follow the lines of enquiry that it had opened up. ‘Vermeer has always been mysterious; one might like him to become a little less so.’ I sensed that his words were meant as a challenge.

Some ten years later I spent a day with John Michael Montias at his home in New Haven, Connecticut. I was making a documentary about Vermeer, for which he had generously agreed to be interviewed. Off camera, he said he was disappointed that so little use had been made of his work by art historians. He had hoped for more to have been discovered about Vermeer’s principal patrons, whose existence he had been the first to reveal. His own days of archival research were over, but, had they not been, that was where he would have focused his attention. I noted what he said but did not act upon it because I was busy with other projects. A few years later, when he passed away, I resolved to look into Vermeer more deeply as soon as I had time.

That did not happen until 2017, when I embarked on a systematic reevaluation of the existing archival evidence on Vermeer and his circle.

preface and acknowledgements

Montias’s Vermeer and His Milieu contains nearly all the important documents, most of which had been discovered by him, alongside a number found by his predecessors. A few other documents have turned up in the years since his death. I was not entirely sure what I was hoping to find in this mass of material, but after four or five years of sifting through it I realized that something startling had emerged from Pandora’s box: previously unseen connections linking much of what is already known about Vermeer. This quickly led to one breakthrough after another. The box seemed to be well and truly open. It was then that I decided I had enough to write this book.

The account of Vermeer that follows is largely and perhaps disconcertingly new. Because I have been fortunate enough to make a number of fresh discoveries about the painter and those close to him, it has been possible to reveal more about his life and work than was previously known. Much of this information may be unfamiliar, even to those well acquainted with the copious existing literature on the artist.

I hope the result is an enriched understanding of Vermeer’s personality, and of the beliefs and emotions that drove him to create his pictures. Seeing him in a new way has also entailed placing him in a fresh perspective. I have written at some length about the wars through which he lived and the fierce religious conflicts in which he may have participated, and for good reason. Once Vermeer’s place in history is properly understood, it becomes clear that he was one of a chosen few who built the values on which a tolerant and liberal civilization, our own even, might be based. This is a side of Vermeer that has been lost from view, although I believe that those who have truly loved his work have often sensed its presence.

Montias’s tip was a good one. Many of the new finds presented here concern Vermeer’s patrons. Information of this kind inevitably changes how we think about an artist’s work to some degree. But in the case of Vermeer its effect is both transformative and surprising. That is because it contains the key to a wide range of meanings long hidden within his paintings, yet clear as day once seen. When I started work on this book, I never anticipated the way in which my research would eventually lead me to challenge most if not all of my own preconceptions about his pictures, including even what kind of pictures they are. But that is what has happened. In almost no case does my account of a given

preface and acknowledgements

picture match up with anything previously written about it. This does not reflect any vigorous striving for originality on my part. It is simply the consequence of having to reconceive Vermeer’s work on the basis of what I have stumbled upon. I hope the effect will be stimulating, at the least.

I have been helped to write this book by a great many people, but foremost I would like to thank my loyal editor and publisher, Stuart Proffitt. Stuart commissioned the book more than twenty years ago, at a time when neither of us had much idea of how it would turn out. His steadfast patience and support for this voyage of discovery, through thick and thin, have meant the world to me.

Eleo Gordon, brought in by Stuart to help edit the book even as it was being written, offered sound and welcome advice, as well as much encouragement when it was sorely needed. Richard Mason copyedited the final text with forbearance, good humour and a beady eye. Picture researcher Cecilia Mackay made many helpful suggestions, especially for the contextual illustrations. Thanks to her the book is more vivid and approachable than it might otherwise have been. Richard Duguid and Sandra Fuller oversaw the production process, more extended than expected, with exceptional care and sensitivity. Vartika Rastogi has coordinated the efforts of the various cooks in the kitchen with enthusiasm, energy and grace. My agent, Georgina Capel, has provided wise guidance throughout, as she has now for decades.

Numerous friends and colleagues in the Netherlands have generously given of their time. Where appropriate they are credited in the footnotes, but several must also be mentioned here. Taco Dibbits, director of the Rijksmuseum, has been talking Vermeer with me for more than thirty years, off camera and on. He and his team, including Elles Kamphuis and Hendrikje Crebolder, allowed me the extraordinary privilege of more or less unlimited access to the extensive exhibition of Vermeer’s work staged by the Rijksmuseum in 2023, just as I was concluding my research for this book. During more than twenty visits to that exhibition, I was able to refine my thinking about many of Vermeer’s most compelling pictures. I am deeply grateful to everyone involved for allowing me this rare opportunity to study the artist’s works at first hand, in depth, over such a protracted period of time. It was an unforgettable experience.

xxxv

preface and acknowledgements

I am also grateful to Gregor Weber, former Head of the Department of Fine Arts at the Rijksmuseum and a lead curator of the Vermeer exhibition. In conversation he kindly shared some of the fruits of his own research into Vermeer, offering valuable insights in particular into the Catholic milieu of Vermeer’s mother-in-law. My own conclusions about the painter’s religious affiliations vary greatly from those of Gregor, but life would be dull indeed without space for difference. The cheerful toleration of opposing views has long been part of the fabric of Dutch intellectual life, and is one of the principal themes of this book.

While lecturing at the Mauritshuis in 2019, I came to know Jane Choy-Thurlow, who was kind enough to take an interest in my work on Vermeer and helped to unearth a number of letters that shed light on the life of his one important patron in Rotterdam. Those letters were a thread I needed when I was in the heart of the labyrinth. I am very glad to have met Jane when I did.

Another important encounter at the Mauritshuis took place many years earlier, in the late 1990s, when I visited the museum with my friend and colleague Roger Parsons. We were making a television documentary about Vermeer and were lucky enough to be granted an interview with the conservator Jørgen Wadum about Girl with a Pearl Earring and the View of Delft. He had just cleaned both pictures and shared innumerable insights about the way in which they had been painted, which greatly deepened my understanding of Vermeer’s methods. I am also grateful to the conservator Ari Wallaerts, who shared the results of his research into the composition of St Praxedis, concerning pigment analysis in particular, confirming that it is indeed an autograph painting by Vermeer.

My long-time researcher Eugénie Aperghis-van Nispen tot Sevenaer investigated the family trees of numerous individuals in Vermeer’s circle of friends and patrons, as well as finding out a great deal about the treatment of the mentally ill in seventeenth-century Delft, among other things. It was Eugénie who called my attention to the presence of Hendrik Doedijns in the household of Vermeer’s last patron, Postmaster Van Swoll: a small but important detail. She also organized two extremely helpful trips, to the Netherlands and Germany, arranging for me to meet numerous people with knowledge of the subjects that interested me. I have been exceptionally lucky to have had Eugénie as an ally for so many years.

xxxvi

preface and acknowledgements

Friso Lammertse and Pieter Roelofs were kind enough to meet me, at the Boymans van Beuningen Museum and Rijksmuseum respectively, and share their own ideas about aspects of Vermeer’s practice. In Dresden, I was given the warmest welcome by curator Uta Neidhardt and conservator Christoph Schölzel, who shared with me their remarkable discovery of the painting-within-a-painting that had lurked for so many years beneath the surface of Vermeer’s Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window. Their find and its implications gave a tremendous impetus to my own work, encouraging me to continue in a direction that would eventually lead to a great many other discoveries.

I have also benefited immeasurably from conversations with a great many experts on Dutch religion. In Amsterdam, Henk Leegte, pastor of the Mennonite Church of Amsterdam, and Piet Visser, religious historian, taught me a great deal about Dutch nonconformist Christianity in general and the Mennonites in particular. In Rotterdam, I had the remarkable good fortune to meet Tjaard Barnard, preacher at the Remonstrant church there. During the course of a few hours and many coffees, Tjaard shed much light on the Remonstrant movement and the place of Jacobus Arminius within it. Shortly afterwards the unfailingly helpful chief administrator of the Remonstrant Church, Kitty Havinga, persuaded a member of her own Rotterdam congregation to help me track down a particular group of documents concerning Vermeer and his friends in the Delft archive. Not only did my new Remonstrant assistant, Titus van Hille, give me many days and hours of his time entirely gratis, but he did so while welcoming a family of refugees into his home in Rotterdam: Remonstrants are clearly as generous now as they were in Vermeer’s time. Titus went on to do tremendous detective work on my behalf, uncovering the previously unknown and extremely significant location of the house in Delft where Vermeer’s main patrons lived: a golden piece of data which confirmed my strong suspicions about the painter’s religious milieu. I cannot thank Titus enough.

Bas van der Wulp, who knows the Delft archives as well as anyone, has patiently fielded my queries about Vermeer off and on for a great many years. He was kind enough to meet me and share his thoughts about his own most recent discovery, namely a burial record describing the painter’s funeral arrangements, which dispelled the myth that

xxxvii

preface and acknowledgements

Vermeer died in poverty. He had also helped me, many years previously, to understand the temperament of Vermeer’s troubled and probably deranged brother-in-law Willem. The distinguished archival researcher Jaap van der Veen was also kind enough to meet me and share his expertise on the vanished world of the seventeenth century. We talked about the wealth of Vermeer’s mother-in-law, Maria Thins, which I had rather underestimated up to that point. We also discussed Pieter Claesz van Ruijven’s closeness to Vermeer, confirmed by Jaap’s discovery of their signatures side by side on a document of 1672, and he helpfully impressed upon me the importance of understanding seventeenth-century Dutch naming traditions.

Albert Vossepoel, an expert on Spinoza, met me at the Spinozahuis in Rijnsburg, where we explored the philosopher’s views on love and his close links to the Collegiants. Adam Boreel’s biographer Francesco Quatrini kindly gave me a tutorial on the Collegiant movement and the role played within it by Adrian Paets.

Bettiena Drukker volunteered to decipher Johannes Taurinus’s Reflections on the Parable of the Samaritan Woman, a text which only survives in its first edition: no easy task given the devilishly difficult Gothic font in which it is set. Having rendered it into readable Dutch, Bettiena also helped to translate a number of key passages, and all at a time when she was extremely busy with her own projects.

Paul Abels, who is immensely knowledgeable about the religious life of Delft (and Gouda) in the seventeenth century, kindly agreed to cast a critical eye over the entire book in manuscript. His comments, observations and objections made for numerous improvements to the original text, and I am deeply grateful to him for his help.

In New York, Peter Carey has been a constant inspiration. More or less as soon as I had completed my previous book, on Caravaggio, Peter insisted that I prioritize Vermeer forthwith, even drafting a mock agreement on the napkin of a New York restaurant and then insisting that I sign it. Obligations incurred under such circumstances have to be honoured.

Closer to home, in Sussex, my sister Elizabeth kindly read a number of passages in manuscript and gave her valuable opinions on matters of theology, in particular. My friends Neil Gonzalez and Christian Birmingham have each in their different ways given me hope and

xxxviii

preface and acknowledgements

encouragement. Nick Gosset has set me straight many times. Carol Reed, as ever, has done what she can.

I must also thank Dr Kees Kaldenbach, with whom I have sporadically corresponded about Vermeer over many years. I also owe a debt of gratitude to Jonathan Janson, whom I have never met, but whose website, ‘Essential Vermeer’, has been a mine of helpful information since its inception more than twenty years ago.

Thanks also to Mrs. F. Cossee-De Wijs, retired senior archivist of the Gemeentearchief Delft, who kindly helped with the translation and interpretation of certain key documents touching on the Van Ruijven family home.

My assistant Kate Adams has been a perfect pillar of strength and has done extraordinary things to make this book possible. I remember in particular a gruelling four-week stint during which she managed not only to elicit its entire narrative structure from me, but also to transcribe it into a five-metre flow chart running much the length of my office, which then became the touchstone for everything I wrote. Had she not gone to such lengths I would surely never have completed my text in time for it to be published when it needed to be. Kate has also obtained numerous hard-to-find books and documents and has helped frequently with translation. She has phoned people who needed to be phoned and found pictures that needed to be found, more times than I can say. Unlike me, she is the epitome of calm under pressure, and I cannot thank her enough.

In conclusion, I must thank my older son, Arthur, who applied his own keen advocate’s mind to the final draft of the manuscript, pointing out numerous errors, inaccuracies and unnecessary ambiguities while providing elegant solutions in almost every case. I must also thank my younger son, Vincent, for putting up with me on the many (very many) occasions on which I, as he put it, ‘Vermeered’ him. The Vermeering is all done for now.

Finally, my deepest debt of all is to my dear wife, the messenger. She saw it, just by looking at the pictures.