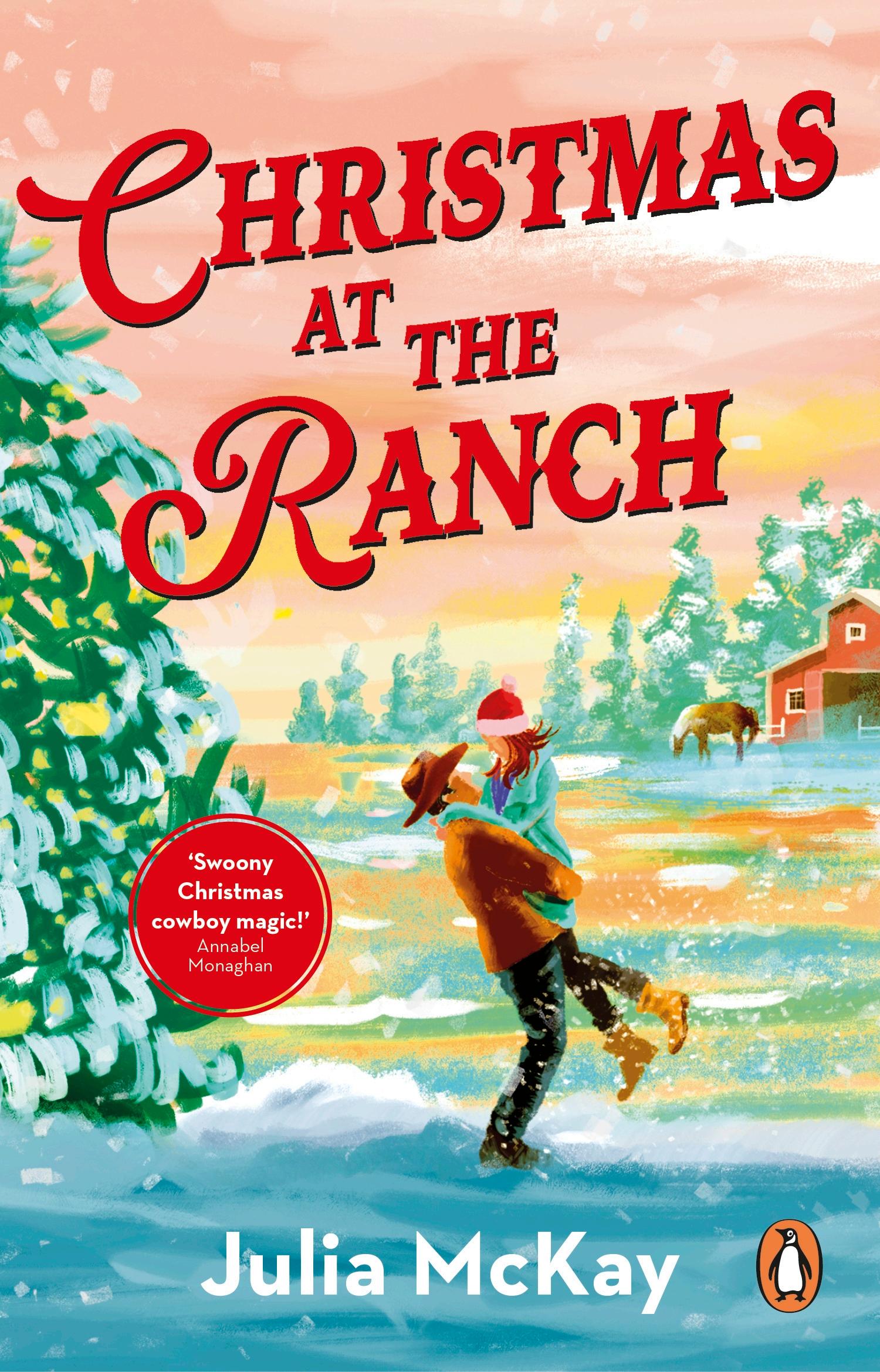

Julia McKay

TRANSWORLD PUBLISHERS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW

penguin.co.uk

Originally published in the US by G.P. Putnams’s Sons

This edition published by arrangement with G.P. Putnam’s Sons, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, division of Penguin Random House LLC

First published in Great Britain in 2025 by Penguin Books an imprint of Transworld Publishers

001

Copyright © Marissa Stapley 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

This book is a work of fiction and, except in the case of historical fact, any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Book design by Shannon Nicole Plunkett

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9781804998694

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

For Maia, because this one was her idea

D ear Diary, I met a guy.

I kissed a guy. Twice, actually. Three times. Four? Possibly forty.

I kissed him so many times I lost count. His name is Tate Wilder. He has amber- brown eyes and a voice like hot maple syrup poured on snow. I know you had to wait eighteen years for the story of my first real kiss, but trust me, dear Diary, it was worth the wait . . .

It all started last night. Another one of my parents’ parties with the crowd of friends and family they invited to this huge “cottage” we’ve rented for the holidays. Screeches of laughter drifted up through the floorboards, waking me at, according to the clock in my cavern of a bedroom, just past one in the morning. It’s not really a cottage we’re staying in, it’s a mansion— but at least the monstrosity is perched at the edge of a frozen lake in the Algonquin Highlands, surrounded by snow- topped pines and ice- glazed granite cliffs. So pretty. So serene. So obvious no one in my family got the memo about peace and quiet.

As I tried to go back to sleep the music started again: Cousin Reuben, playing his New Wave Xmas: Just Can’t Get Enough record for the tenth time. He and my dad had some kind of falling-out in their thirties and didn’t

speak for over a decade. But apparently, that’s all water under the bridge now because they’re starting some new business venture together.

Earlier in the night I was down in the kitchen, pouring glasses of water and gently suggesting my family members eat some real food instead of nibbling on or ignoring the canapés my mother served before she and Aunt Bitsy got into the martinis. As I reheated the platters of beef tenderloin and potatoes dauphinoise the hired chef had prepared and no one had touched, I overheard Aunt Bitsy and my mother talking about me.

“She’s so responsible, Cass,” Bitsy said. Then, in a sotto voice that wasn’t sotto at all, she leaned toward my mother and added, “And a bit boring, honestly.” At this, my mother laughed lightly and looked over at me, her smile apologetic. But then Bitsy raised her voice and said, “Shouldn’t you be out somewhere, causing trouble with the local boys, Emory? That’s what I would have been doing at eighteen. And why didn’t you invite any friends here? Aren’t you bored?”

My parents had suggested I invite a friend or two, and I had to pretend they were all busy over the holidays. When the truth, as you know, is that I don’t fit in at Blackford Academy, the private school I go to. Just as I don’t fit in with my family. I even did a science fair project on DNA, asked my parents to provide samples, secretly hoping the findings would reveal I had been switched at birth. Maybe my real family lived in a cozy house in the suburbs . . . Maybe I had brothers or sisters or both . . .

But no. I’m one hundred percent the only daughter of

Cassandra and Stephen Oakes. My great-great-grandfather opened a distillery in Gananoque during Prohibition and turned it into a booze empire. My father then added a financial arm of the company, and hoped I would work there with him one day, allowing his ne’er- do- well cousins and other relatives to run the distillery portion of things. He didn’t take it well this summer when I finally worked up the nerve to tell him I was planning to study journalism instead of business in college. We’ve been distant with each other ever since. I guess he thought I was someone else entirely— and, for my part, I’m hurt that when I tried to let him in on my true dreams, he acted like they were nothing.

My mother, meanwhile, used to be a charity fundraising executive but she stopped working outside of the house after I was born and is now known for throwing great parties and overseeing at least one home décor refresh per year. She still fundraises for charities, but sometimes I wonder if she thinks about why she’s doing it— or if it’s turned into a social thing for her, rather than any sort of philanthropy.

I somehow turned out quiet, studious, introverted— and, up until tonight, someone who had never even had a proper first kiss.

I’m getting to that part.

“Our Emory is eighteen going on forty,” my mother said to Aunt Bitsy— and she may have meant it as a compliment, but I abandoned the platters of food to go back upstairs, feeling stung by her words, laden with even more disappointment than before.

Back in Toronto last month, when my parents told me

we were renting a lake house for the December holiday break, I imagined quiet nights in, just the three of us. Reading by the fire, playing board games. Exactly the kind of holiday an overly mature eighteen- year- old would want. Finally, I thought. For my last Christmas officially at home before university next year, they’ve decided to do something they know I’ll love. My dad has forgiven me for disappointing him. For wanting to chase my own dream instead of his.

Instead, my parents planned an elaborate three- week party beginning the moment school break started. And they ignored me when I suggested that sharing a house with the relatives they spend the rest of the year— and portions of their lives— avoiding was probably a bad idea. Now my dad and Reuben are in business together, and I can’t put my finger on why that feels like trouble, but it does.

Anyway. This is not about them.

Because— the guy . I’m getting there, I promise. I just need to make sure I have all the details straight, so I never forget any of this. I’m like a reporter, and this is my own life— and I finally have an exciting dispatch!

Annoyed by the noise coming up through the floor, I got out of bed to open my window for some fresh air, but was greeted instead by cigar smoke and the loud voice of another one of my father’s cousins— Richard? Hank?— telling my father what a genius idea all this was. Who wouldn’t want to stay in a luxury “cottage” on my parents’ dime, eating and drinking for free? I thought, as the densely bitter- smelling cigar smoke billowed through the window.

I felt so lonely.

But just before I closed the window, I heard a sound. Like a ghost, wailing from the direction of the lake. I think my father and his cousin heard it, too, because they stopped talking abruptly. Then, the howl started up again. It was mysterious, otherworldly, the strangest noise.

My first thought was that maybe someone was hurt, and I had to get outside and help. I pulled a sweatshirt over my flannel pajamas, found a parka and winter boots by the back stairs, and crept outside. No one noticed me leave. My father and his cousin had gone back inside through the patio doors. I stood still, listening, until I heard it once more: the groaning sound bubbling up from underneath the still- thin ice of the lake. I headed for the shore to check it out.

“Hello?” I called. “Is anyone out there? Are you hurt?”

The light of the full moon was fading the stars, but still, I’d never seen so many of them. I stopped walking when I reached the edge of the lake. I looked up and took the cosmos in. I wonder now if I made a wish on all those stars, perhaps for a cure for my loneliness.

I heard the crackling of sparks and embers. I looked to my left and saw a bonfire down the snowy beach, someone sitting in a Muskoka chair, staring into the flames. He was wearing a plaid jacket and a Stetson hat.

“What’s that noise coming from the lake?” I asked. He waved me over. As I got closer, I realized he was about my age. He had a strong jaw and full lips— the bottom one fuller than the top. Eyes that flashed like sparks from his fire. The words “Wilder Ranch” were stitched in white across the pocket of his flannel jacket.

“It’s the sound the lake makes when it freezes every year,” he explained when I was close, and the way he spoke to me made me feel like we were continuing a conversation we had already started— like I hadn’t just appeared in front of him out of nowhere.

I’ll admit, I forget most of what he said next. Something about how it was sunny today, so the ice melted a little, and now it was dark, and the ice was refreezing. Expanding and contracting, science, et cetera. As he spoke, all I could think about was how his smile flashed at me like a shooting star I wanted to chase, to coax out again and again, to keep for my own. He stood up from his chair and I realized he was very tall. I’m tall, too, so it’s nice when I’m not looking down at a person. Especially a guy. He was slim, kind of gangly, but his shoulders were broad under his flannel. And his hair, peeking out from beneath that Stetson, was sandy brown with sun- kissed ends, as if he hadn’t had it cut since summer.

He continued with his explanation about why the water made that noise under the ice, but all I could think was how unexpected it was to be standing on the shore of a lake in winter, talking to a handsome guy in front of a bonfire— when moments before I had been stuck in my bedroom, staring down three weeks of misery.

Was I dreaming?

I must have shivered then, and he mistook it for my being cold. He invited me to come sit by his fire and pulled over another Muskoka chair. I explained who I was and apologized for all the noise my family was making, disturbing the peaceful setting. He just shrugged and

said it was fine, he hadn’t heard anything, really. Then he looked over at me and smiled again. I was mesmerized.

“I mean, hey, who doesn’t love hearing ‘Last Christmas’ by Wham! on repeat something like . . . eleven times?” he said.

In that moment, I knew I liked him. Already. And I decided I wanted him to like me back so badly. I needed to try to be someone else. Not the shy awkward girl I’m known as at school. The one who had worn bottle- thick glasses until she recently got contacts and would rather stay home with a book than go out on weekends.

“I’m Emory,” I said, hoping the smile on my face was as casual and appealing as his. I nodded at his beer bottle. “You don’t happen to have a drink for me, do you?”

There it was, that smile again— now wider. He was looking at me with the interest I had been seeking, the same delighted surprise I felt the second I saw him. I tossed my hair over my shoulder, glad I’d allowed my mother’s stylist to have her way, pre– family reunion. My normally flat chestnut- brown hair was layered into a long bob that flipped up at the ends.

“So, a city girl just walks onto my beach, asking for a drink?” he said, his eyes dancing in the firelight. “What do you think this is, a bar? Maybe I should be asking for ID.”

I tilted my head, doing my absolute best at insouciance. I pretended I did this sort of thing all the time. “What makes you think I’m a city girl?”

At this, he laughed— and if his voice was maple syrup on snow, his laugh was butterscotch in a double boiler. “The haircut, the outfit . . .” he began.

I looked down at myself. “I’m wearing flannel pants with snowflakes on them.”

“Hmm, that’s true. And yet there’s just something city- ish about you.”

Now it was my turn to smile. “You’re right. I’m from Toronto.”

“I’ll try to overlook that,” he said as he pulled a halfempty six- pack from under his Muskoka chair. “Here you go, City Girl.”

Crooked smile. (Him.) Heart palpitations. (Me.)

“Help yourself,” he said.

I don’t usually drink beer, or anything at all, but I pretended I did, taking a bottle and twisting off the cap like I had done it tons of times before, then casually sipping while trying not to grimace. He saw it anyway and raised an eyebrow.

“I guess Labatt 50 isn’t exactly your flavor,” he said, and my heart fluttered again because, dear Diary, we were flirting. I’ve never flirted with anyone— unless you count Maxwell Corbett at school, who told his friends last year I’d be “pretty without glasses” and “maybe if she weren’t so tall.” Then, the next time I saw him, I said “hi,” started to blush furiously, and ran away. But you know all that already.

“It’s my favorite,” I replied, taking a longer sip— and then, embarrassingly, gagging and nearly spitting it out. Beer is gross.

“I can get you something else,” he offered.

“Maybe this really is a local bar?” I countered.

“Yeah, it’s a real dive,” he said with a laugh. “But actually, there are some nice parts.”

He gestured behind him and I realized that just beyond us, down a snowy hill, were fenced paddocks and stables. The wooden boards of the buildings were hung with red and white Christmas lights. I peered into the moonlit darkness at the magical setting spread out before me, feeling as if I had wished it into existence.

“Wilder Ranch,” he said, and I could hear the pride in his voice. “It’s mine. Well, mine and my dad’s.”

“I love horses,” I breathed, because this is true. It was a relief to drop the pretenses. “Why is it called Wilder?”

“That’s my last name. I’m Tate. Tate Wilder.”

“Nice to meet you, Tate.” I tried one more sip of the beer and sighed. After just five minutes of pretending to be a cool girl from the city, I was tired of it. “I don’t actually drink,” I said, handing him back his beer bottle. “But I would love to see your horses.”

He tilted his head then. “You ride?” he said.

I told him about the stables I used to take lessons at, just outside the city limits. “I joined the show team and practically lived there until I was sixteen. But then I stopped,” I told him.

“Let me guess, because you got a boyfriend?”

I could have said yes, kept up the charade— but I shook my head. I didn’t want to lie to him. I liked him too much, already.

“Actually, I discovered the honor roll. And my desire to get into a good university.”

He looked away from me then, seemed thoughtful. “Well, sure,” he finally said. “I’ll take you on a tour of the ranch if you want. Just let me finish this.” He shook the beer bottle I had just returned to him and tipped it back.

“Meantime, do you know how to skip rocks? They make a cool sound at this stage in the lake’s freezing process.”

Since I wasn’t pretending to be someone else anymore, I was able to tell him I was the kind of person who avoided throwing or catching things at all. This got me a rumble of a laugh that made me feel like the bonfire had transferred itself to my chest.

“I’ll teach you,” he said, moving down the shore, gathering stones as he went. When he returned, he set a pile of them at my feet.

“It’s all in the flick of the wrist,” he said— or something to that effect. I was distracted by how close he was to me then. And how good he smelled. Like leather soap and hay, pine needles and woodsmoke, and something else I suspected was just him . I watched as he demonstrated, keeping the stone in his hand instead of releasing it. When he finally let the stone fly, the deep pinging sound it made as it ricocheted across frozen water reminded me of a video game or a spaceship’s controls.

“That can’t be real.” Much like the otherworldly groaning from beneath the lake ice I had listened to earlier, the noise the stone made as it skipped didn’t sound like it should be coming from a lake at all.

“Lakes in winter are full of surprises.”

Honestly? I was feeling the same way about him.

“Now you try,” he said, handing me a smooth, flat stone. My first attempt was a fail: I threw too hard and the stone landed several feet out with a single resonant clunk. He stepped even closer and said, “May I?” His hand hovered just above my wrist.

I wonder if that was the moment everything changed—

or if everything had changed already by then. As I was standing on that shore with him, under the starriest winter sky I had ever seen, Tate Wilder touched me and a shower of sparks flooded my system. My stomach swooped, my knees weakened, I truly understood the meaning of the word “swoon.” This could not possibly be what it’s always like when one person puts their hand on another person’s wrist. Could it? Is this what I’ve been missing?

With the utmost effort, I dragged my thoughts away from how his touch made me feel and back to what he was trying to show me. I perfected the snapping motion and my stone did exactly what it was supposed to: ricocheted across the ice four times, then five, pinged and ponged while I cheered and laughed. So did he.

“Okay, so, that ranch tour,” he said. “Still interested?” He thought for a moment. “There’s also a party in town I was invited to, if that’s more your speed.”

“I want to see your ranch.”

I helped him put handfuls of snow on the fire to extinguish it. Then he led me down the snowy embankment into the valley.

Soon, we were standing at the edge of a paddock, watching a herd of about a dozen horses gallop in the moonlight. He whistled. One of them, her gray- white coat shining palely, trotted over. When she reached the fence, she nuzzled Tate’s shoulder while he laughed and patted her, then reached into the pocket of his plaid flannel jacket to pull out a bag of mints, those round white ones.

“I have to keep these on me at all times,” he said with

a sweet laugh I was almost getting used to. He popped a mint in his mouth, offered me one, then held a mint out to the horse while she stamped her hooves, appearing to protest the order in which the mints had been distributed. But then she picked the mint delicately from his palm.

“She’s beautiful,” I said.

“Isn’t she? Her name is Mistletoe. Because of the marking on her face, see?” He ran his finger along the pure white blaze running from between her eyes to just above her soft muzzle. Indeed, there was an unusual shape at the top, just like a little sprig of festive leaves.

I was wishing he would touch me that softly. I was wishing a lot of things.

“She was born on Christmas Eve, five years ago. Mistletoe was the perfect name for her.”

“She really seems to like you.” The horse was nuzzling him again, rubbing her face against his broad shoulders— and I have to admit, I was still envious.

“It’s the mints,” he said with another laugh, stroking her muscular neck while she nickered in his ear. “But yeah, she’s pretty much mine. I helped train her. We get along well.” Now his voice became even softer and the horse pricked her ears forward. “You’re a good girl, aren’t you?” he murmured.

Diary, I cannot stress this enough: Listening to Tate Wilder croon sweet nothings into a horse’s ear was probably the most charming thing I have ever experienced. I had the sudden urge to say something stupid like, “Well, since we’re standing near Mistletoe, maybe we should . . .”

But that’s not how the kissing happened.

He told me Mistletoe was expecting a foal in the new year and that he and his dad were so excited about this. He then pointed out the other horses in the small herd that were his favorites: a compact chestnut Thoroughbred gelding named Jax, a beautiful bay Dutch warmblood mare named Dolly, a sturdy quarter horse named Walt.

“But Mistletoe is the prettiest,” I found myself saying, earning a nod of approval and agreement from him.

He showed me the stables next. Inside, they were cozy, dimly lit. The air smelled of the bodies and warm breath of the horses in their stalls. Of sweet grain and hay, leather soap and dust. He explained that they boarded some of the horses, owned some of them, currently operated a small breeding facility— but that he wanted to start a riding school someday so they could keep all their horses, rather than have to sell any of them.

He asked me questions about the show team I had been on, and my time on the Trillium circuit. He asked if I missed it, and I told him that until tonight, I hadn’t realized just how much. Not the competition element, but being around horses.

“Maybe I shouldn’t have given it up so easily,” I said.

“It’s never too late to start again,” he replied.

The last stall at the end of the final row contained a donkey named Kevin. “He’s a rescue,” said Tate.

A rescue donkey , dear Diary. He’s a stout little character with a spiky gray mane who, apparently, prefers carrots to mints— so we gave him a few of those from a bucket near his stall while Kevin hee- hawed happily.

Eventually, we climbed up into the hayloft to sit side

by side on a tall stack of bales, talking some more as the moonlight flowed in through a hole in the roof covered in waterproof clear plastic, which Tate said was on his and his dad’s endless list of things to fix at the ranch.

We passed one of his beers back and forth and I got used to the taste. He asked me about my school, where I lived in Toronto, how I had ended up at the huge rental house next to his property for the holidays, how long I was staying. I asked him more questions about life at the ranch, who else besides his dad was around to help with that long to- do list. He said it was just the two of them; he didn’t have any siblings. And his mom was gone, she had died. In the silence after he said that, the words “I’m so sorry” faded on my lips. I wasn’t sure what to say at all. But then, he turned and stared into my eyes so intently I couldn’t speak or move. He took a deep breath, then held it— as if weighing whether to speak again or not.

“It was one year ago tonight, actually,” he finally said. “That my mom died. I never talk about her, but . . .” He let that sentence wander off, unfinished, then began again. “I was feeling pretty bad tonight, just wanted to be on my own, to light a fire and look at the stars, hoping that might”— he paused again, swallowed, looked away from me for a moment—“make me feel better, I guess. And then . . .” Our gazes connected once more. Those eyes, like the embers from his bonfire. I couldn’t get enough of his gaze. His smile was slow, transforming his face from sad to sweet to everything I had ever dreamed of in a person. His voice was husky when he said, “And then, City Girl, you walked onto my beach, and I forgot my problems altogether.”

Kissing him was, all at once, the only thing I could think about. I had to take this chance or I’d regret it forever. I leaned toward him, tilted my head, and his lips met mine.

So, what exactly was my first kiss like? Maybe the first few seconds were awkward, sort of like riding a bike until you figure it out. Scary, a little wobbly— and then, all at once, you’re balanced, you’re rolling, you feel like you’re flying, wind in your hair, beautiful confidence filling you up. That’s how it felt to kiss Tate Wilder. Like I could fly away, go anywhere, be anyone. Like being too smart or too tall or too weird didn’t matter anymore.

His hands were in my hair, and then he was pulling back and stroking my cheek, telling me softly that he thought I was so beautiful, so unexpected. “Where did you come from?” he said. “Did I dream you?”

“I’ve been wondering the same,” I replied.

His hair and skin smelled like woodsmoke combined with the clean, cool tang of winter air. I remember my hand on the back of his neck, the warmth of his skin under my fingers, the softness of his hair with its leftover sun- kisses at the ends. His Stetson had fallen onto one of the hay bales.

He tasted a little bit like beer, and those scotch mints he kept in his pocket for his horse, and something else spicy, like cloves or cinnamon. He tasted like the best parts of Christmas.

I will remember my first kiss until the end of time, I swear.

Hours must have passed, because when we finally stopped kissing, I pulled away from him and opened my

eyes to see the first streaks of dawn in the slip of sky visible through the barn roof.

“I’d better get you back to that big old house before anyone in your family notices you’re gone,” he said.

I didn’t want to go, but I suppose all kisses must end— even absolutely epic ones that last for hours. I felt sad about it being over, but then he looked at me like I was a treasure he’d just found and didn’t want to lose. It made the fact that we weren’t kissing anymore a little easier to bear.

We held hands as we picked our way along the snowy shore. When we got to the back door of the rental house, he said, “Can I see you again?” Which was precisely what I’d been wishing on the very last star flickering out in the sky that he’d say.

Before I could even think about it, the words “I’m yours for the next three weeks” flew out of my mouth. Instead of making him appalled at my forwardness, they caused him to pull me close and kiss me again.

“Don’t tease me, City Girl,” he murmured. Then, “Come by the ranch later today, mid-afternoon? I’ll be done with all my chores by then, and we can go for a trail ride if you want. Get you back on a horse, since you said you miss it so much.”

I told him that sounded perfect, because it did. Then, I opened the back door and stepped inside, already filled with longing for him. I watched him through the little window at the top of the door as he made his way down the snowy forest path, back toward the magical place where he lived.

When he looked back, I didn’t duck away in embar-

rassment: I waved, and he waved back— and then, dear Diary, I melted. I drizzled down the door, landed on the welcome mat, and lay there, an Emory-shaped puddle, daydreaming about him until who knows how long later, when I heard my mother in the kitchen and had to reassemble my atoms and sneak upstairs to bed.

It was the most perfect night of my life— one that feels like it could be the beginning of everything.