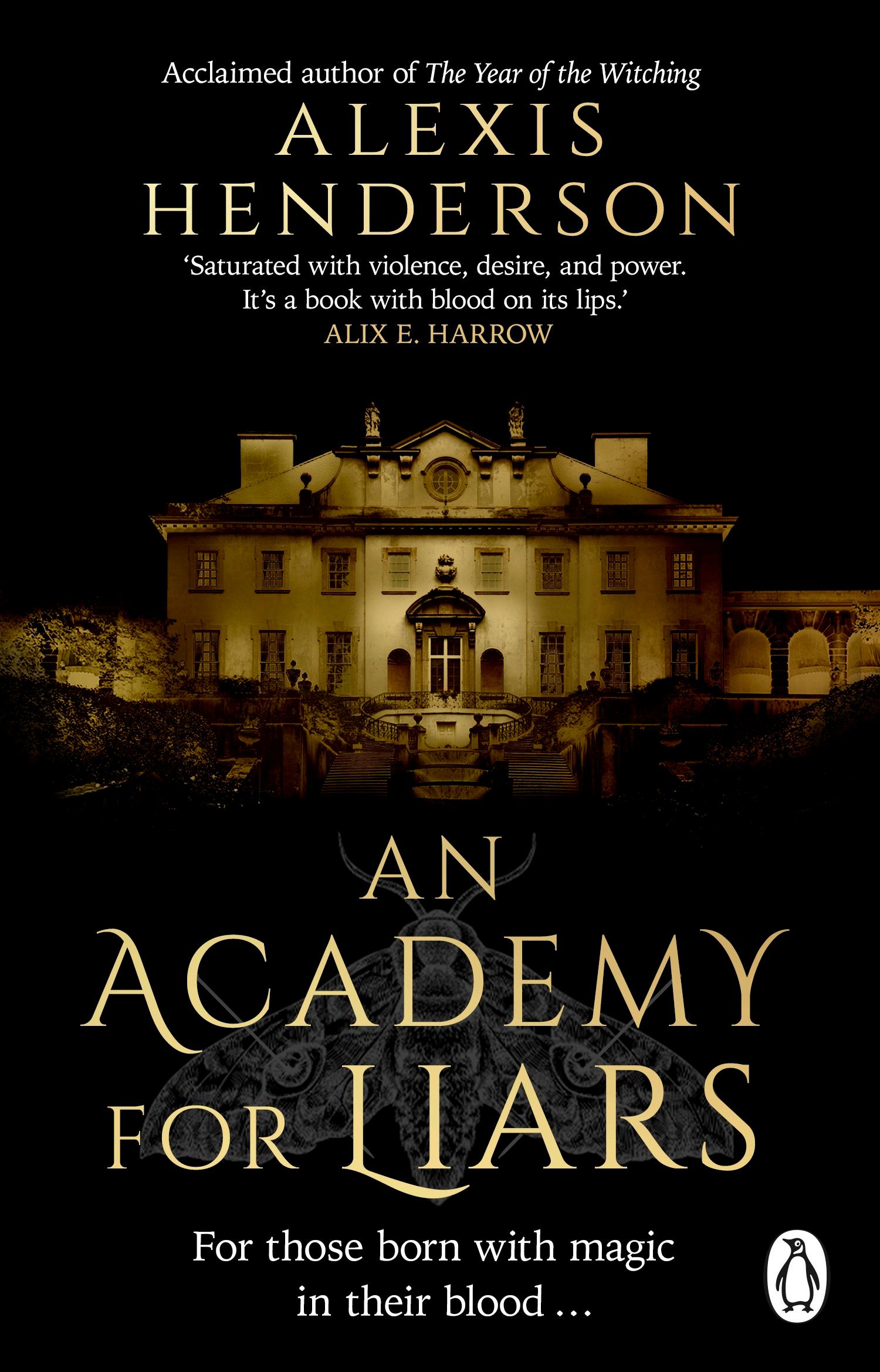

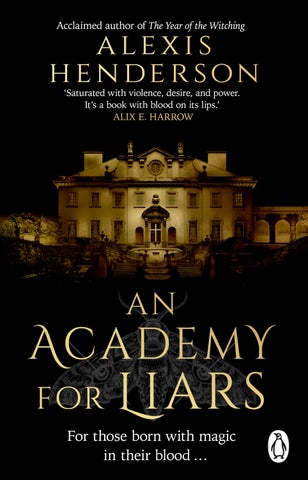

ALEXIS

HENDERSON

PENGUIN BOOK S

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London sw11 7bw penguin.co.uk

First published in Great Britain in 2024 by Bantam an imprint of Transworld Publishers Penguin paperback edition published 2025

Copyright © Alexis Henderson 2024

The moral right of the author has been asserted

This book is a work of fiction and, except in the case of historical fact, any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental. Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Book design by Daniel Brount

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d02 yh68.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn: 9781804993651

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

This one is for Alice

TTHERE WAS SOMETHING in the bathroom mirrors. Lennon fi rst noticed when she was standing between them, preparing for her own engagement party. One of the mirrors hung above the sink behind her; the other hung above the sink in front of her. Standing between the two, she gazed with glassy eyes at the reflections of herself reflecting one another, on and on, shrinking into the dark and distant ether.

Every one of them looked miserable, which was to be expected. Lennon had realized some time ago that her misery was less a problem with the wedding than with her. She had been in a bad way for months unmoored, discordant, occupying her own body with a sense of unease, the way one might in an airport terminal or the lobby of a rent-by-the-hour motel. Her own flesh and bone a kind of liminal space.

HERE WAS SOMETHING in the bathroom mirrors. Lennon fi rst noticed when she was standing between them, preparing for her own engagement party. One of the mirrors hung above the sink behind her; the other hung above the sink in front of her. Standing between the two, she gazed with glassy eyes at the reflections of herself reflecting one another, on and on, shrinking into the dark and distant ether.

Every one of them looked miserable, which was to be expected. Lennon had realized some time ago that her misery was less a problem with the wedding than with her. She had been in a bad way for months unmoored, discordant, occupying her own body with a sense of unease, the way one might in an airport terminal or the lobby of a rent-by-the-hour motel. Her own flesh and bone a kind of liminal space.

She’d hoped things would change with the engagement. So she’d attended the cake tastings and the dress fittings, and she’d made a deposit on the venue and secured a fi lm photographer, who would be

She’d hoped things would change with the engagement. So she’d attended the cake tastings and the dress fittings, and she’d made a deposit on the venue and secured a fi lm photographer, who would be 1

HENDERSON

flying in from out of state for the occasion. She’d sent wax-sealed invites across the country to her family members and a few seat-fi ller friends. And now here she was, alone in her bathroom regretting everything and so desperate to be somewhere, anywhere, else that she would’ve almost rather died than face the engagement party outside her bedroom door. It was something of a miracle, then, that she finished her makeup. Her body seemed to perform the act without her, and when it was done, she stared at all of her faces in the mirror and saw someone, many someones, that she didn’t know.

flying in from out of state for the occasion. She’d sent wax-sealed invites across the country to her family members and a few seat-fi ller friends. And now here she was, alone in her bathroom regretting everything and so desperate to be somewhere, anywhere, else that she would’ve almost rather died than face the engagement party outside her bedroom door. It was something of a miracle, then, that she finished her makeup. Her body seemed to perform the act without her, and when it was done, she stared at all of her faces in the mirror and saw someone, many someones, that she didn’t know.

And then she slapped herself.

And then she slapped herself.

One hand raised all of the other Lennons in the mirror raising their hands with her and a sharp pop across her freshly blushed cheek. The slap carried down through the legion of her reflections and then stopped.

One hand raised all of the other Lennons in the mirror raising their hands with her and a sharp pop across her freshly blushed cheek. The slap carried down through the legion of her reflections and then stopped.

One of the Lennons in the mirror didn’t strike its cheek. It didn’t move at all really, except to smile, its lips pulling up at the edges, as if the corners of its mouth were attached to strings that had been sharply tugged. Then it sidestepped out of line, edging up through the ranks, walking toward her. It was like her in almost every way bony bronzed arms sparsely tattooed, thin high nose spattered with freckles, long braids unfurling halfway down her back but there was one glaring difference between Lennon and the defecting reflection in the mirror: she had eyes, but this . . . thing did not. It strode toward her, smiling all the while.

One of the Lennons in the mirror didn’t strike its cheek. It didn’t move at all really, except to smile, its lips pulling up at the edges, as if the corners of its mouth were attached to strings that had been sharply tugged. Then it sidestepped out of line, edging up through the ranks, walking toward her. It was like her in almost every way bony bronzed arms sparsely tattooed, thin high nose spattered with freckles, long braids unfurling halfway down her back but there was one glaring difference between Lennon and the defecting reflection in the mirror: she had eyes, but this . . . thing did not. It strode toward her, smiling all the while.

Lennon wheeled to face the mirror behind her, saw nothing except the same girl moving toward her, through the shift ing ranks of the line. Panicked, she glanced around the bathroom but saw that she was alone.

Lennon wheeled to face the mirror behind her, saw nothing except the same girl moving toward her, through the shift ing ranks of the line. Panicked, she glanced around the bathroom but saw that she was alone.

The defector was edging closer now, stepping gingerly around its peers, sometimes weaving between them, letting its fingers trail along

The defector was edging closer now, stepping gingerly around its peers, sometimes weaving between them, letting its fingers trail along

2

their bare shoulders as it passed them by. It stopped only when it’d reached the reflection nearest Lennon and stepped up onto its tiptoes so that it was an inch or two taller. The aberration in the mirror slid its hands around Lennon’s waist from behind, the way that a lover might. It opened its mouth and pressed a kiss into the soft juncture where neck curves into shoulder.

their bare shoulders as it passed them by. It stopped only when it’d reached the reflection nearest Lennon and stepped up onto its tiptoes so that it was an inch or two taller. The aberration in the mirror slid its hands around Lennon’s waist from behind, the way that a lover might. It opened its mouth and pressed a kiss into the soft juncture where neck curves into shoulder.

Lennon stumbled, backing into the sink, arms wheeling, swiping a jar of cotton balls off the counter on her way to the floor. It shattered on impact beside her.

Lennon stumbled, backing into the sink, arms wheeling, swiping a jar of cotton balls off the counter on her way to the floor. It shattered on impact beside her.

There was a beat of silence, followed by a knock at the door. She knew it was her fiancé, Wyatt, checking in on her. She was now more than an hour late to her own engagement party, and she could tell from the strained tenor of his voice that he was running out of patience. “Are you okay?”

There was a beat of silence, followed by a knock at the door. She knew it was her fiancé, Wyatt, checking in on her. She was now more than an hour late to her own engagement party, and she could tell from the strained tenor of his voice that he was running out of patience. “Are you okay?”

“Yes, fine! I’ll be out in a second.” Gingerly, Lennon scooped up the glass shards and placed them in the trash, risking glances at the mirror all the while. The thing was gone, but she swore she could still feel the wet crescent of its kiss at the curve of her shoulder.

“Yes, fine! I’ll be out in a second.” Gingerly, Lennon scooped up the glass shards and placed them in the trash, risking glances at the mirror all the while. The thing was gone, but she swore she could still feel the wet crescent of its kiss at the curve of her shoulder.

She scrambled to her feet and fled the bathroom.

She scrambled to her feet and fled the bathroom.

The house was full of Wyatt’s faculty friends from the university where he worked. One of them, a WASPy woman in a tasteful tweed blazer, abruptly stopped whispering when Lennon emerged from the bedroom. She bore the decided stink of significance, which to Lennon smelled a lot like Chanel No. 5. The woman looked at Lennon, slightly startled, as if she were an intruder instead of someone who lived there.

The house was full of Wyatt’s faculty friends from the university where he worked. One of them, a WASPy woman in a tasteful tweed blazer, abruptly stopped whispering when Lennon emerged from the bedroom. She bore the decided stink of significance, which to Lennon smelled a lot like Chanel No. 5. The woman looked at Lennon, slightly startled, as if she were an intruder instead of someone who lived there.

This was the uncomfortable reality of her life in Denver. The obligatory check-ins from vague acquaintances upon the event of a police murder, or the subsequent protests that followed it. The off handed inquiries about the details of her DNA makeup, her nationality, her place of birth, the texture of her hair, and if it was really

This was the uncomfortable reality of her life in Denver. The obligatory check-ins from vague acquaintances upon the event of a police murder, or the subsequent protests that followed it. The off handed inquiries about the details of her DNA makeup, her nationality, her place of birth, the texture of her hair, and if it was really

hers. Then there were the acquaintances at Wyatt’s dinner parties who inquired about the color of her eyes and how she’d come by them and what or who she’d been crossed with. Then came the questions about her parentage, and her parents’ parentage, because those same acquaintances now wondered if the parents of her parents had eyes the same muddy hazel as hers. It was a gentle othering, or perhaps more aptly, a distancing, that made Lennon feel it was impossible to connect with others in the close and complicated ways she wanted to. She’d since stopped trying.

hers. Then there were the acquaintances at Wyatt’s dinner parties who inquired about the color of her eyes and how she’d come by them and what or who she’d been crossed with. Then came the questions about her parentage, and her parents’ parentage, because those same acquaintances now wondered if the parents of her parents had eyes the same muddy hazel as hers. It was a gentle othering, or perhaps more aptly, a distancing, that made Lennon feel it was impossible to connect with others in the close and complicated ways she wanted to. She’d since stopped trying.

Lennon, still badly shaken by her encounter in the bathroom, forced a smile and shouldered her way through the house, a midcenturystyle ranch with an interior courtyard, complete with a cactus garden and a large koi pond stocked to capacity. Every year Wyatt forgot to remove the fish before the fi rst freeze of winter. She remembered one of the fi rst nights they’d spent in the house. There was a blizzard raging outside and they’d lost power and were forced to sleep on the floor of the living room, in front of the fi replace for warmth. Come dawn, Wyatt woke with a start and a muttered “Fuck.”

Lennon, still badly shaken by her encounter in the bathroom, forced a smile and shouldered her way through the house, a midcenturystyle ranch with an interior courtyard, complete with a cactus garden and a large koi pond stocked to capacity. Every year Wyatt forgot to remove the fish before the fi rst freeze of winter. She remembered one of the fi rst nights they’d spent in the house. There was a blizzard raging outside and they’d lost power and were forced to sleep on the floor of the living room, in front of the fi replace for warmth. Come dawn, Wyatt woke with a start and a muttered “Fuck.”

He snatched a bucket from the supply closet, shuffled into the kitchen to fi ll it with warm water from the sink, and took a meat tenderizer from the drawer before staggering outside, trudging through calf-high snowdrift s to the very edge of the koi pond, where he dropped to his knees and began to hammer the thick crust of ice. He removed several heavy plates of ice from the surface of the pond before proceeding to extract each of the eight koi by hand, placing them in the bucket of warm water to thaw. He then hauled them all into the house and put them straight into the bathtub, which he fi lled with warm water.

He snatched a bucket from the supply closet, shuffled into the kitchen to fi ll it with warm water from the sink, and took a meat tenderizer from the drawer before staggering outside, trudging through calf-high snowdrift s to the very edge of the koi pond, where he dropped to his knees and began to hammer the thick crust of ice. He removed several heavy plates of ice from the surface of the pond before proceeding to extract each of the eight koi by hand, placing them in the bucket of warm water to thaw. He then hauled them all into the house and put them straight into the bathtub, which he fi lled with warm water.

Lennon had sat on the bathroom floor, arms folded on the edge of the tub, chin atop them, watching the koi stir back to life. She even

Lennon had sat on the bathroom floor, arms folded on the edge of the tub, chin atop them, watching the koi stir back to life. She even

touched a few of them, let her fingers skim along their slick spines as they emerged from their slumber. But one of the koi did not rouse to her touch. It floated motionless at the bottom of the tub. Panicked, Lennon plucked it from the water and hastily swaddled it in a hand towel. Cradling the fish to her chest, she carried it to the kitchen, where Wyatt stood, stress-smoking a joint. He took the half-frozen koi corpse from her bare-handed, leaving the damp towel behind, and studied it by the pale morning light that washed in through the windows.

touched a few of them, let her fingers skim along their slick spines as they emerged from their slumber. But one of the koi did not rouse to her touch. It floated motionless at the bottom of the tub. Panicked, Lennon plucked it from the water and hastily swaddled it in a hand towel. Cradling the fish to her chest, she carried it to the kitchen, where Wyatt stood, stress-smoking a joint. He took the half-frozen koi corpse from her bare-handed, leaving the damp towel behind, and studied it by the pale morning light that washed in through the windows.

“You know, it’s not the cold that kills them,” he said, as if to absolve himself. The dead fish dribbled water onto the freshly cleaned kitchen floor. Wyatt didn’t seem to notice. Or if he did, he didn’t care. “They suffocate. They can’t breathe under the ice.”

“You know, it’s not the cold that kills them,” he said, as if to absolve himself. The dead fish dribbled water onto the freshly cleaned kitchen floor. Wyatt didn’t seem to notice. Or if he did, he didn’t care. “They suffocate. They can’t breathe under the ice.”

“Can’t they breathe the water?”

“Can’t they breathe the water?”

“They breathe the oxygen in it,” he said, rather matter-of-factly, and turned to throw the koi corpse into the trash. It struck the bottom of the bin with an ugly thump. “But under the ice there isn’t enough.”

“They breathe the oxygen in it,” he said, rather matter-of-factly, and turned to throw the koi corpse into the trash. It struck the bottom of the bin with an ugly thump. “But under the ice there isn’t enough.”

Lennon began to love him then, foolish as it was. She had been so young then, and it had seemed to her that Wyatt knew everything about everything. She thought him the smartest person she’d ever met and thought herself all the more alluring for being the recipient of his sparing love . . . or if not that, then the object of it. Had he bent to one knee and asked her to marry him then, she was confident she would have said yes, being the bright-eyed little idiot that she was.

Lennon began to love him then, foolish as it was. She had been so young then, and it had seemed to her that Wyatt knew everything about everything. She thought him the smartest person she’d ever met and thought herself all the more alluring for being the recipient of his sparing love . . . or if not that, then the object of it. Had he bent to one knee and asked her to marry him then, she was confident she would have said yes, being the bright-eyed little idiot that she was.

As it turned out, she would wait another year before Wyatt proposed (if one could even call it a proposal). He had broached the subject in the front yard, not on one knee but standing beside the empty koi pond. All of the fish were dead and gone, lost to another winter,

As it turned out, she would wait another year before Wyatt proposed (if one could even call it a proposal). He had broached the subject in the front yard, not on one knee but standing beside the empty koi pond. All of the fish were dead and gone, lost to another winter,

soon to be replaced by new and expensive imports, long-finned butterfly koi flown in from Kyoto.

soon to be replaced by new and expensive imports, long-finned butterfly koi flown in from Kyoto.

Wyatt had no ring at the time, or question to ask. He knew what the answer would be already. He’d simply said that he liked the idea of marrying in the fall.

Wyatt had no ring at the time, or question to ask. He knew what the answer would be already. He’d simply said that he liked the idea of marrying in the fall.

Tonight, the koi appeared comfortable, swimming beneath the cover of their lily pads, their faint fins moving like fabric in the wind. A few guests academics and admin whose names she didn’t know stood smoking and sipping cocktails around the water’s edge. They waved at her, with some awkwardness, and Lennon waved back as she cut quickly across the courtyard.

Tonight, the koi appeared comfortable, swimming beneath the cover of their lily pads, their faint fins moving like fabric in the wind. A few guests academics and admin whose names she didn’t know stood smoking and sipping cocktails around the water’s edge. They waved at her, with some awkwardness, and Lennon waved back as she cut quickly across the courtyard.

She found Wyatt in the kitchen, slicing paper-thin slivers of lime alongside two of his colleagues. He was good-looking, with his shirtsleeves rolled up to his elbows, his forearms shapely and covered in a soft down of curly brown hair. He had wide-set blue eyes, and he was tall and gangly with pale skin faintly freckled; a large, distinctly aristocratic nose; and a boyish, canted smile, which he flashed at her, forcibly, as she stepped alongside him.

She found Wyatt in the kitchen, slicing paper-thin slivers of lime alongside two of his colleagues. He was good-looking, with his shirtsleeves rolled up to his elbows, his forearms shapely and covered in a soft down of curly brown hair. He had wide-set blue eyes, and he was tall and gangly with pale skin faintly freckled; a large, distinctly aristocratic nose; and a boyish, canted smile, which he flashed at her, forcibly, as she stepped alongside him.

“I’m sorry,” she said as he pulled her into a hug. “I don’t know if it’s those new meds or what, but I think I saw something in the bathroom ”

“I’m sorry,” she said as he pulled her into a hug. “I don’t know if it’s those new meds or what, but I think I saw something in the bathroom ”

“We’ll talk later,” he said through gritted teeth, smiling all the while.

“We’ll talk later,” he said through gritted teeth, smiling all the while.

Wyatt’s closest friend and fellow professor, the blond and wiry George Hughes, stood beside him aggressively shaking the contents of a cocktail strainer. As he worked, he relayed the intricacies of his latest research trip to Russia. A PhD in architecture, he had gone to study some significant brutalist structure there. “It’s the most amazing building. The spirit of communist antiquity quite literally made concrete. I had to travel almost sixty miles north by snowmobile to

Wyatt’s closest friend and fellow professor, the blond and wiry George Hughes, stood beside him aggressively shaking the contents of a cocktail strainer. As he worked, he relayed the intricacies of his latest research trip to Russia. A PhD in architecture, he had gone to study some significant brutalist structure there. “It’s the most amazing building. The spirit of communist antiquity quite literally made concrete. I had to travel almost sixty miles north by snowmobile to

6

reach it, and I hiked the last half of the journey on foot, limping along with a pair of broken snowshoes that barely clung to my boots, and they still wouldn’t let me in to see it.”

reach it, and I hiked the last half of the journey on foot, limping along with a pair of broken snowshoes that barely clung to my boots, and they still wouldn’t let me in to see it.”

Beside George stood their friend Sophia, measuring small scoops of ice into their respective copper mule mugs. On that night, she wore her hair which was the pale beige of a peanut shell combed carefully over one shoulder. Her sweater was a tasteful gray, half-tucked into the waistband of her slacks. She puckered her lips and kissed the air in Lennon’s general direction by way of greeting. “If it isn’t the blushing bride.”

Beside George stood their friend Sophia, measuring small scoops of ice into their respective copper mule mugs. On that night, she wore her hair which was the pale beige of a peanut shell combed carefully over one shoulder. Her sweater was a tasteful gray, half-tucked into the waistband of her slacks. She puckered her lips and kissed the air in Lennon’s general direction by way of greeting. “If it isn’t the blushing bride.”

Lennon made herself smile.

Lennon made herself smile.

Sophia was good at performing kindness (or maybe she was kind, and Lennon too bitter to admit it). The two of them had been friends once. Or something close to friends anyway. Sophia had transferred into the University of Colorado just aft er Wyatt joined the faculty. Sophia was married, but her husband oft en traveled for work and wasn’t around much, so in their early days in Denver, Sophia was a constant presence. Lennon hadn’t minded this, as she found that she liked Wyatt better when Sophia was there. He smiled more when she was around, and they quarreled less.

Sophia was good at performing kindness (or maybe she was kind, and Lennon too bitter to admit it). The two of them had been friends once. Or something close to friends anyway. Sophia had transferred into the University of Colorado just aft er Wyatt joined the faculty. Sophia was married, but her husband oft en traveled for work and wasn’t around much, so in their early days in Denver, Sophia was a constant presence. Lennon hadn’t minded this, as she found that she liked Wyatt better when Sophia was there. He smiled more when she was around, and they quarreled less.

But things had changed over time. While Lennon cycled through therapists and endured brief stints at various hospitals and rehab facilities around the city, Sophia (a psychologist) went on to secure research grants, publish papers in well-respected journals, defend her dissertation, and secure a coveted internship at the University of Colorado Hospital, where she worked now.

But things had changed over time. While Lennon cycled through therapists and endured brief stints at various hospitals and rehab facilities around the city, Sophia (a psychologist) went on to secure research grants, publish papers in well-respected journals, defend her dissertation, and secure a coveted internship at the University of Colorado Hospital, where she worked now.

The two fell out of touch. Wyatt was the only bridge between them at this point, but he seemed increasingly content to observe the separate spheres of his life with Lennon and his life at the university. So Sophia had become less their friend, and more Wyatt’s, specifically.

The two fell out of touch. Wyatt was the only bridge between them at this point, but he seemed increasingly content to observe the separate spheres of his life with Lennon and his life at the university. So Sophia had become less their friend, and more Wyatt’s, specifically.

ALEXIS HENDERSON

The two confided in each other as colleagues, shared in the varying triumphs and miseries of their respective fields Wyatt divulging the difficulties of his research, its lack of funding, the grants he’d wanted and failed to acquire, and Sophia sharing the rigors of her life as a clinician, struggling through the last half of her internship, pinning her hopes on the faculty positions that she hoped would open in neighboring colleges. Lennon was largely left alone.

The two confided in each other as colleagues, shared in the varying triumphs and miseries of their respective fields Wyatt divulging the difficulties of his research, its lack of funding, the grants he’d wanted and failed to acquire, and Sophia sharing the rigors of her life as a clinician, struggling through the last half of her internship, pinning her hopes on the faculty positions that she hoped would open in neighboring colleges. Lennon was largely left alone.

The party settled for dinner on the back patio. Lennon and Wyatt sat at either end of a long banquet table. Over dinner, Lennon watched her fiancé through the faint tendrils of pot smoke that traced through the air between them. He had the kind of startling charisma she had always coveted, a certain thrall that drew people like moths to light and made everyone want to be known and loved by him. She could see it now, as he chatted among his peers, single-handedly commanding the table so that even those on the opposite end of it craned out of their seats and strained forward to catch his every word. They were the kind of people who mistook greatness for its shadow. As long as they were in the presence of brilliance, they too were brilliant by proxy. Lennon knew this about them because she was once the same struck dumb with awe and utterly convinced that Wyatt’s presence alone was enough to elevate her above the murk of her own mediocrity.

The party settled for dinner on the back patio. Lennon and Wyatt sat at either end of a long banquet table. Over dinner, Lennon watched her fiancé through the faint tendrils of pot smoke that traced through the air between them. He had the kind of startling charisma she had always coveted, a certain thrall that drew people like moths to light and made everyone want to be known and loved by him. She could see it now, as he chatted among his peers, single-handedly commanding the table so that even those on the opposite end of it craned out of their seats and strained forward to catch his every word. They were the kind of people who mistook greatness for its shadow. As long as they were in the presence of brilliance, they too were brilliant by proxy. Lennon knew this about them because she was once the same struck dumb with awe and utterly convinced that Wyatt’s presence alone was enough to elevate her above the murk of her own mediocrity.

Lennon had been a college freshman then dewy- eyed and jejune studying English literature at New York University. Wyatt had been a poet in residence at one of the neighboring colleges. She had attended one of his readings, and he’d taken an interest in her because, apparently, she looked like an actress from a French art house fi lm he’d loved as a teenager. Lennon, for her part, had never watched it (and never bothered to either).

Lennon had been a college freshman then dewy- eyed and jejune studying English literature at New York University. Wyatt had been a poet in residence at one of the neighboring colleges. She had attended one of his readings, and he’d taken an interest in her because, apparently, she looked like an actress from a French art house fi lm he’d loved as a teenager. Lennon, for her part, had never watched it (and never bothered to either).

Nevertheless, they fell in love the way most people do which is to say they felt as though they were experiencing love for the fi rst

Nevertheless, they fell in love the way most people do which is to say they felt as though they were experiencing love for the fi rst

8

8

time. It was all so fast and intense, and Lennon had the suspicion that this was the root cause of her unraveling. She had learned, at a young age, that change was her trigger. It could be change for better or for worse it didn’t matter; her body interpreted the stimuli in the same way. So when the panic attacks fi rst began, she wasn’t entirely surprised. What did surprise her, though, was their violence. The tears and the vomiting and the vertigo. She stopped counting how many classes she’d missed, lying naked on the bathroom floor, waiting for the waves of terror to subside.

time. It was all so fast and intense, and Lennon had the suspicion that this was the root cause of her unraveling. She had learned, at a young age, that change was her trigger. It could be change for better or for worse it didn’t matter; her body interpreted the stimuli in the same way. So when the panic attacks fi rst began, she wasn’t entirely surprised. What did surprise her, though, was their violence. The tears and the vomiting and the vertigo. She stopped counting how many classes she’d missed, lying naked on the bathroom floor, waiting for the waves of terror to subside.

By the end of that semester, the fi rst of her sophomore year, she found herself in a psychiatric ward, where she would remain for eight weeks. Lennon dropped out of college shortly aft er she was discharged, on the recommendation of her psychiatrist and the urging of her family members and Wyatt, who by this time had become almost as close as family to her. Perhaps they all knew what Lennon only allowed herself to accept months later: she wasn’t fit to continue on at college. She was not brilliant in the ways that Wyatt, George, and Sophia were. She was neither an artist nor a scholar nor even a particularly promising college student. She was simply very, very sick. Her parents urged her to move back home to their house in a Florida retirement community, which sounded like hell to Lennon. So, when Wyatt invited her to move to Denver, Colorado, where he had taken a job as a professor in the University of Colorado’s MFA program, Lennon decided to go with him. She moved into his house carefully slotting herself into the empty spaces of his life and became, officially, his live-in girlfriend. Or, unofficially, his housewife. She was twenty.

By the end of that semester, the fi rst of her sophomore year, she found herself in a psychiatric ward, where she would remain for eight weeks. Lennon dropped out of college shortly aft er she was discharged, on the recommendation of her psychiatrist and the urging of her family members and Wyatt, who by this time had become almost as close as family to her. Perhaps they all knew what Lennon only allowed herself to accept months later: she wasn’t fit to continue on at college. She was not brilliant in the ways that Wyatt, George, and Sophia were. She was neither an artist nor a scholar nor even a particularly promising college student. She was simply very, very sick. Her parents urged her to move back home to their house in a Florida retirement community, which sounded like hell to Lennon. So, when Wyatt invited her to move to Denver, Colorado, where he had taken a job as a professor in the University of Colorado’s MFA program, Lennon decided to go with him. She moved into his house carefully slotting herself into the empty spaces of his life and became, officially, his live-in girlfriend. Or, unofficially, his housewife. She was twenty.

Lennon plucked a smoking joint from the cinders of a nearby ashtray and toked. Bored, she shifted her attention down the table and noticed that Wyatt and Sophia were nowhere to be seen. This didn’t

Lennon plucked a smoking joint from the cinders of a nearby ashtray and toked. Bored, she shifted her attention down the table and noticed that Wyatt and Sophia were nowhere to be seen. This didn’t

arouse her suspicion at fi rst. It was a casual event; half of those in attendance had already finished their meals and dispersed to different corners of the house. A few professors puzzled over the contents of Wyatt’s bookshelves. Grad students stood around the koi pond smoking weed, watching the fish circle. A group of poets huddled together in the kitchen, gossiping over the rims of their cocktail glasses.

Twenty minutes passed. Sophia and Wyatt remained missing.

Lennon dragged on her joint once more and got up to look for them, a part of her knowing already what she would fi nd when she did. She wasn’t sure what it was about this night that made her want to confi rm her darkest suspicions. But it imbued her with a kind of bravery she had not known before. In the end, it didn’t matter what led her to fi nd them together in the primary bathroom Wyatt hunched over Sophia, his bare belly pressed hard to the small of her back only that she did.

arouse her suspicion at fi rst. It was a casual event; half of those in attendance had already finished their meals and dispersed to different corners of the house. A few professors puzzled over the contents of Wyatt’s bookshelves. Grad students stood around the koi pond smoking weed, watching the fish circle. A group of poets huddled together in the kitchen, gossiping over the rims of their cocktail glasses. Twenty minutes passed. Sophia and Wyatt remained missing. Lennon dragged on her joint once more and got up to look for them, a part of her knowing already what she would fi nd when she did. She wasn’t sure what it was about this night that made her want to confi rm her darkest suspicions. But it imbued her with a kind of bravery she had not known before. In the end, it didn’t matter what led her to fi nd them together in the primary bathroom Wyatt hunched over Sophia, his bare belly pressed hard to the small of her back only that she did.

Sophia’s trousers were pooled about her ankles, her lace panties pulled taut between her straining thighs. She was smiling and saying the nice things that men like to hear when they’re inside you. The sorts of things Lennon could never bring herself to say about Wyatt, not because they weren’t true (though maybe they weren’t) but because she didn’t know how to say them in a way that made them seem true. But Sophia did, and Wyatt responded in turn. They moved together as one, and as Sophia pressed forward the edge of the countertop cut deep into her stomach and her breath fogged the mirror.

Sophia’s trousers were pooled about her ankles, her lace panties pulled taut between her straining thighs. She was smiling and saying the nice things that men like to hear when they’re inside you. The sorts of things Lennon could never bring herself to say about Wyatt, not because they weren’t true (though maybe they weren’t) but because she didn’t know how to say them in a way that made them seem true. But Sophia did, and Wyatt responded in turn. They moved together as one, and as Sophia pressed forward the edge of the countertop cut deep into her stomach and her breath fogged the mirror.

It was dark in the bathroom, so neither Wyatt nor Sophia noticed Lennon in the doorway, or the fact that her reflection disobeyed her once again, breaking the tether that bound likeness to master. It was the same eyeless aberration that had appeared earlier that evening, and when it met Lennon’s gaze, it grinned.

It was dark in the bathroom, so neither Wyatt nor Sophia noticed Lennon in the doorway, or the fact that her reflection disobeyed her once again, breaking the tether that bound likeness to master. It was the same eyeless aberration that had appeared earlier that evening, and when it met Lennon’s gaze, it grinned.

LLENNON LEFT THE party. She edged past the koi pond and the grad students who encircled it, down the long driveway, and stepped out into the street, where Wyatt’s car was parked parallel to the sidewalk a few houses down.

It was a silver Porsche 911, a hand-me-down gift from Wyatt’s father to commemorate his successful dissertation defense. Wyatt had never allowed Lennon to drive it. He didn’t trust her behind the wheel or with much of anything, really. To him, everything she did (unplugging the iron before they left to run errands) or said (“I love you, the way you deserve to be loved”) was cast in a hard shadow of uncertainty.

ENNON LEFT THE party. She edged past the koi pond and the grad students who encircled it, down the long driveway, and stepped out into the street, where Wyatt’s car was parked parallel to the sidewalk a few houses down.

It was a silver Porsche 911, a hand-me-down gift from Wyatt’s father to commemorate his successful dissertation defense. Wyatt had never allowed Lennon to drive it. He didn’t trust her behind the wheel or with much of anything, really. To him, everything she did (unplugging the iron before they left to run errands) or said (“I love you, the way you deserve to be loved”) was cast in a hard shadow of uncertainty.

Lennon unlocked the doors of Wyatt’s car and climbed inside. The leather of the seat was cold against her bare thighs. She didn’t check the mirrors before slipping the key into the ignition. But her gaze flickered back to the house. Though she didn’t know it then, this was the last she’d see of it for some time.

Lennon unlocked the doors of Wyatt’s car and climbed inside. The leather of the seat was cold against her bare thighs. She didn’t check the mirrors before slipping the key into the ignition. But her gaze flickered back to the house. Though she didn’t know it then, this was the last she’d see of it for some time. She began to drive. Aimlessly at fi rst letting the car drift from 2

She began to drive. Aimlessly at fi rst letting the car drift from

ALEXIS HENDERSON

empty lane to empty lane and then with purpose, pressing down on the gas pedal, picking up speed, the suburbs the trim little lawns and tasteful houses, the organic grocery stores and Citizens Banks, the Mattress Firms and storage facilities smearing past the windows in a blur. She thought a bit about the aberration she’d seen in the mirror of the bathroom. The girl with no eyes who was her but . . . not. And Lennon wondered what she wanted, or if she was some harbinger of bad fortune, or if not that, then the cause of it.

empty lane to empty lane and then with purpose, pressing down on the gas pedal, picking up speed, the suburbs the trim little lawns and tasteful houses, the organic grocery stores and Citizens Banks, the Mattress Firms and storage facilities smearing past the windows in a blur. She thought a bit about the aberration she’d seen in the mirror of the bathroom. The girl with no eyes who was her but . . . not. And Lennon wondered what she wanted, or if she was some harbinger of bad fortune, or if not that, then the cause of it.

Her thoughts returned to Wyatt.

Her thoughts returned to Wyatt.

What she realized then as she sat in his car was that she had been so obsessed with trying to bridge the gap between them to prove herself precocious and smart and worthy enough to be the recipient of his love that she’d made the grave error of mistaking the want of closeness for closeness itself. But one was not a sufficient substitute for the other. Her love or her yearning for it was not, and would never be, enough, which is why Wyatt was with Sophia tonight, and not her.

What she realized then as she sat in his car was that she had been so obsessed with trying to bridge the gap between them to prove herself precocious and smart and worthy enough to be the recipient of his love that she’d made the grave error of mistaking the want of closeness for closeness itself. But one was not a sufficient substitute for the other. Her love or her yearning for it was not, and would never be, enough, which is why Wyatt was with Sophia tonight, and not her.

By the time Lennon reached the abandoned mall on the cusp of the suburbs, she knew what she was preparing to do. There were blood thinners in the glove compartment, prescription strength. Wyatt kept them there after suffering a pulmonary embolism years ago, before he met Lennon that very nearly killed him. He’d warned her once to make sure that she never mixed them up with her antidepressants the pills looked similar because the blood thinners had no antidote. If you overdosed on them, there was nothing any doctor or hospital could do for you, apart from watch you slowly bleed out from the inside.

By the time Lennon reached the abandoned mall on the cusp of the suburbs, she knew what she was preparing to do. There were blood thinners in the glove compartment, prescription strength. Wyatt kept them there after suffering a pulmonary embolism years ago, before he met Lennon that very nearly killed him. He’d warned her once to make sure that she never mixed them up with her antidepressants the pills looked similar because the blood thinners had no antidote. If you overdosed on them, there was nothing any doctor or hospital could do for you, apart from watch you slowly bleed out from the inside.

Surely, Lennon thought, downing a bottle would do the trick.

She decided she would find some bathroom stall or stockroom at the heart of the place where there would be no one to disturb her. No one to intervene, which should’ve been a good thing . . . but as Lennon

Surely, Lennon thought, downing a bottle would do the trick. She decided she would find some bathroom stall or stockroom at the heart of the place where there would be no one to disturb her. No one to intervene, which should’ve been a good thing . . . but as Lennon

stepped out into the deserted parking lot, intervention was exactly what she wanted. A sign, a symbol, the grasping hand of some meddling but benevolent god who would reach down through a break in the clouds and shake her senseless, until she was forced to believe really and truly that her life had meaning and that she was destined for something more than mediocrity. She wanted salvation and she found it in the form of a phone booth half-devoured by crawling ivy, standing in the fl ickering halo of one of the last streetlights in the parking lot that was still shining.

stepped out into the deserted parking lot, intervention was exactly what she wanted. A sign, a symbol, the grasping hand of some meddling but benevolent god who would reach down through a break in the clouds and shake her senseless, until she was forced to believe really and truly that her life had meaning and that she was destined for something more than mediocrity. She wanted salvation and she found it in the form of a phone booth half-devoured by crawling ivy, standing in the fl ickering halo of one of the last streetlights in the parking lot that was still shining.

The booth was oak and old-fashioned with yellow stained-glass windows so thoroughly fogged that even if there had been a person within, Lennon likely wouldn’t have been able to see them. The leaves of the ivy plant that bound the booth stirred and bristled, though there was no wind that night. As Lennon stood staring, the phone began to ring, a shrill and tinny sound like silver spoons striking the sides of so many small bells.

The booth was oak and old-fashioned with yellow stained-glass windows so thoroughly fogged that even if there had been a person within, Lennon likely wouldn’t have been able to see them. The leaves of the ivy plant that bound the booth stirred and bristled, though there was no wind that night. As Lennon stood staring, the phone began to ring, a shrill and tinny sound like silver spoons striking the sides of so many small bells.

Lennon decided, at fi rst, to ignore this and started toward the mall with the pill bottle in hand, but the phone kept ringing, louder and louder, as if with increasing urgency. She stopped, turned to the booth, then walked toward it, reluctantly at fi rst, half hoping the ringing would stop before she reached it. But it persisted.

Lennon decided, at fi rst, to ignore this and started toward the mall with the pill bottle in hand, but the phone kept ringing, louder and louder, as if with increasing urgency. She stopped, turned to the booth, then walked toward it, reluctantly at fi rst, half hoping the ringing would stop before she reached it. But it persisted.

Lennon drew open the collapsible doors of the phone booth, stepped inside, and closed them behind her. Its interior was oddly warm and humid, and there was a sulfurous scent thick in the air. The phone was an old black rotary. Its receiver quivered in its cradle with the force of the ringing. Lennon raised it to her ear. There was a sound like static on the line that Lennon recognized as the distant roar of waves breaking. Then a voice: “Do you still have your name?” it asked, as if a name were a thing that could be misplaced, like a wallet or a pair of keys.

Lennon drew open the collapsible doors of the phone booth, stepped inside, and closed them behind her. Its interior was oddly warm and humid, and there was a sulfurous scent thick in the air. The phone was an old black rotary. Its receiver quivered in its cradle with the force of the ringing. Lennon raised it to her ear. There was a sound like static on the line that Lennon recognized as the distant roar of waves breaking. Then a voice: “Do you still have your name?” it asked, as if a name were a thing that could be misplaced, like a wallet or a pair of keys.

She faltered, wondering if this was some sort of prank call or trick question. “It’s . . . Lennon?”

She faltered, wondering if this was some sort of prank call or trick question. “It’s . . . Lennon?”

“Lennon what?”

“Lennon what?”

She grasped for the rest of it, but it didn’t come. She was really high. “Who is this?”

She grasped for the rest of it, but it didn’t come. She was really high. “Who is this?”

“This is a representative from Drayton College.” The voice on the line was a combination of every voice of everyone that Lennon had ever known speaking together at once. A horrid and familiar chorus her mother, her sister and fi rst therapist, her high school boyfriend, her dead grandmother. “We’re calling to congratulate you on your acceptance to the interview stage of your admission process. You should be very proud. Few make it this far. Your interview will take place tomorrow, at your earliest convenience.”

“This is a representative from Drayton College.” The voice on the line was a combination of every voice of everyone that Lennon had ever known speaking together at once. A horrid and familiar chorus her mother, her sister and fi rst therapist, her high school boyfriend, her dead grandmother. “We’re calling to congratulate you on your acceptance to the interview stage of your admission process. You should be very proud. Few make it this far. Your interview will take place tomorrow, at your earliest convenience.”

“I don’t understand. I never applied for anything. I’ve never even heard of Drayton before ”

“I don’t understand. I never applied for anything. I’ve never even heard of Drayton before ”

The question was asked again, with something of an edge this time. “Can you make it, Lennon?” The address, someplace in Ogden, Utah, was then given.

The question was asked again, with something of an edge this time. “Can you make it, Lennon?” The address, someplace in Ogden, Utah, was then given.

At a loss for words, Lennon fumbled for her cell phone, quickly typed the address into her GPS app, and discovered that the location was an eight-hour drive away. It was already nearly midnight: if she were to make it to the interview in time (which was a ridiculous idea in itself), she’d have to drive all night. What kind of program called prospective students the day before their interview? Was this all some sort of twisted prank? Her confusion festered into bitter frustration. “I’m not going anywhere, for an interview or for anything else, until I get some answers about what the fuck is going on.”

At a loss for words, Lennon fumbled for her cell phone, quickly typed the address into her GPS app, and discovered that the location was an eight-hour drive away. It was already nearly midnight: if she were to make it to the interview in time (which was a ridiculous idea in itself), she’d have to drive all night. What kind of program called prospective students the day before their interview? Was this all some sort of twisted prank? Her confusion festered into bitter frustration. “I’m not going anywhere, for an interview or for anything else, until I get some answers about what the fuck is going on.”

A lengthy pause, and then, in a broken, tear-choked whisper that was unmistakably her own: “He will never love you the way you want

A lengthy pause, and then, in a broken, tear-choked whisper that was unmistakably her own: “He will never love you the way you want

to be loved. And if you stay, he will love you even less, until one day you mean nothing to him.”

to be loved. And if you stay, he will love you even less, until one day you mean nothing to him.”

Lennon froze, her hand tightening to a vise grip around the receiver. Her throat began to swell and tighten. “It’s you. From the mirror. Isn’t it? Answer me!”

Lennon froze, her hand tightening to a vise grip around the receiver. Her throat began to swell and tighten. “It’s you. From the mirror. Isn’t it? Answer me!”

“We wish you the best of luck with the next step of your admission process.” There was a soft click. The line went dead.

“We wish you the best of luck with the next step of your admission process.” There was a soft click. The line went dead.

3

LLENNON DROVE THROUGH the night, stopping only to get gas, change her clothes (she kept a gym bag in the back seat of the car), and pee at a run-down rest stop in the red deserts of Wyoming. Through the course of her journey, she made a point to avoid using the rearview mirrors (for fear of what she’d see if she did), only briefly glancing at them when she was forced to. It helped that the highway was mostly empty, with only a few semis sharing the road with her. It was nearing dawn by the time she crossed into Utah. After driving for hours, she arrived in Ogden, stiff from sitting for so long. Strangely, she wasn’t tired.

ENNON DROVE THROUGH the night, stopping only to get gas, change her clothes (she kept a gym bag in the back seat of the car), and pee at a run-down rest stop in the red deserts of Wyoming. Through the course of her journey, she made a point to avoid using the rearview mirrors (for fear of what she’d see if she did), only briefly glancing at them when she was forced to. It helped that the highway was mostly empty, with only a few semis sharing the road with her. It was nearing dawn by the time she crossed into Utah. After driving for hours, she arrived in Ogden, stiff from sitting for so long. Strangely, she wasn’t tired.

As she approached Ogden, she kept replaying the congratulatory phone call from Drayton in her head and she realized that at fi rst, the voice on the line hadn’t been gendered. It had sounded almost automated in its neutrality, and she couldn’t place it as male or female or anything in between . . . until it had become hers. Which begged the question, how had it become hers? And how had it (she?) known about Wyatt’s infidelity? How had it known that she was there to re-

As she approached Ogden, she kept replaying the congratulatory phone call from Drayton in her head and she realized that at fi rst, the voice on the line hadn’t been gendered. It had sounded almost automated in its neutrality, and she couldn’t place it as male or female or anything in between . . . until it had become hers. Which begged the question, how had it become hers? And how had it (she?) known about Wyatt’s infidelity? How had it known that she was there to re-

ceive the call at all? She felt like she was living the loose logic of dreams and wondered for a moment if this was a dream the thing that appeared in the bathroom mirror, Wyatt’s affair with Sophia, the phone call, her own voice warbling over the line. Or if it wasn’t a dream, then perhaps it was a delusion as vivid and convincing as it was tragic . . . and pathetically grandiose. She wondered if perhaps this was some sort of manic episode like the ones she’d suffered in the past. But those episodes had always been characterized by an unwavering sense of conviction in herself and the forces that fueled her delusions, be they genius or the mechanisms of fate. But as her hands tightened, white-knuckled, around the steering wheel, she felt only small and helpless, adrift on a dark tide that carried her to what, she didn’t know.

ceive the call at all? She felt like she was living the loose logic of dreams and wondered for a moment if this was a dream the thing that appeared in the bathroom mirror, Wyatt’s affair with Sophia, the phone call, her own voice warbling over the line. Or if it wasn’t a dream, then perhaps it was a delusion as vivid and convincing as it was tragic . . . and pathetically grandiose. She wondered if perhaps this was some sort of manic episode like the ones she’d suffered in the past. But those episodes had always been characterized by an unwavering sense of conviction in herself and the forces that fueled her delusions, be they genius or the mechanisms of fate. But as her hands tightened, white-knuckled, around the steering wheel, she felt only small and helpless, adrift on a dark tide that carried her to what, she didn’t know.

Lennon kept driving, following the directions on her GPS. She entered a small historic district in the shadow of a mountain, used for skiing in the wintertime. There, the streets were narrow, canopied by the lush branches of the trees that grew on either side. She found her destination at the curve of a large cul-de-sac: an imposing redbrick mansion set far off the street, half-shrouded by a copse of overgrown hawthorns. Its roof was low- slung over the second- story windows, and it made the house look like an old man frowning at her approach.

Lennon kept driving, following the directions on her GPS. She entered a small historic district in the shadow of a mountain, used for skiing in the wintertime. There, the streets were narrow, canopied by the lush branches of the trees that grew on either side. She found her destination at the curve of a large cul-de-sac: an imposing redbrick mansion set far off the street, half-shrouded by a copse of overgrown hawthorns. Its roof was low- slung over the second- story windows, and it made the house look like an old man frowning at her approach.

She parked in the empty driveway and checked her phone. Seven missed calls (three from Wyatt and four from her mother) and twelve text messages (one from Wyatt, five from her mother, six from her older sister, Carly). Lennon left everything unanswered the text messages, the voicemails, and the countless questions she’d asked herself through the duration of her drive got out of the car to rifle through the contents of the trunk, until she found the greaseblackened crowbar resting below the spare tire. She weighed it in both

She parked in the empty driveway and checked her phone. Seven missed calls (three from Wyatt and four from her mother) and twelve text messages (one from Wyatt, five from her mother, six from her older sister, Carly). Lennon left everything unanswered the text messages, the voicemails, and the countless questions she’d asked herself through the duration of her drive got out of the car to rifle through the contents of the trunk, until she found the greaseblackened crowbar resting below the spare tire. She weighed it in both

ALEXIS HENDERSON

hands, nodded to herself as if to summon what little courage she had to muster, and then slammed the trunk shut.

hands, nodded to herself as if to summon what little courage she had to muster, and then slammed the trunk shut.

The yard was large and covered in a dense carpet of grass. The hedges that lined the house were round and well shaped. Lennon tramped through the plush lawn, crowbar in hand, and stepped up onto the porch. The front door was set with a small window of stained glass that distorted the glimpse of the foyer behind it. Hanging on the wall beside the door was a large plaque that detailed the extensive history of the house (apparently it had been owned by some oil baron millionaire from the 1800s).

The yard was large and covered in a dense carpet of grass. The hedges that lined the house were round and well shaped. Lennon tramped through the plush lawn, crowbar in hand, and stepped up onto the porch. The front door was set with a small window of stained glass that distorted the glimpse of the foyer behind it. Hanging on the wall beside the door was a large plaque that detailed the extensive history of the house (apparently it had been owned by some oil baron millionaire from the 1800s).

Lennon knocked three times, hard and in quick succession. A brief pause then footsteps. The door creaked open. A man stood in the threshold, barefoot in a loose linen shirt and pants to match. He was only a little taller than Lennon, maybe six feet even, with lively blue eyes that wrinkled at the edges when he smiled, with all the warmth and fondness you’d expect from a friend who hadn’t seen you for some time. He looked to be in his late forties, and Lennon found him to be almost excessively good-looking.

Lennon knocked three times, hard and in quick succession. A brief pause then footsteps. The door creaked open. A man stood in the threshold, barefoot in a loose linen shirt and pants to match. He was only a little taller than Lennon, maybe six feet even, with lively blue eyes that wrinkled at the edges when he smiled, with all the warmth and fondness you’d expect from a friend who hadn’t seen you for some time. He looked to be in his late forties, and Lennon found him to be almost excessively good-looking.

“Well,” he said, still smiling at her, his teeth so straight and white they looked like a set of dentures, “you must be Lennon.” He glanced down at her crowbar. “Can I take that off your hands?”

“Well,” he said, still smiling at her, his teeth so straight and white they looked like a set of dentures, “you must be Lennon.” He glanced down at her crowbar. “Can I take that off your hands?”

Lennon handed over the crowbar with some reluctance. In retrospect, she wasn’t sure why she did it. She didn’t know or trust this man. She wasn’t sure if he was the only one in the house. But when he’d asked that question, and made to reach for the crowbar, her resolve had abruptly soft ened . . . and a calm had washed over her, as though she’d taken a Valium.

Lennon handed over the crowbar with some reluctance. In retrospect, she wasn’t sure why she did it. She didn’t know or trust this man. She wasn’t sure if he was the only one in the house. But when he’d asked that question, and made to reach for the crowbar, her resolve had abruptly soft ened . . . and a calm had washed over her, as though she’d taken a Valium.

He stooped slightly, leaning her crowbar against the wall. “I’m Benedict. Just like the breakfast dish,” he said, straightening, and ush-

He stooped slightly, leaning her crowbar against the wall. “I’m Benedict. Just like the breakfast dish,” he said, straightening, and ush-

ered her inside with a flourish of his hand. He closed the door behind her but didn’t lock it.

ered her inside with a flourish of his hand. He closed the door behind her but didn’t lock it.

The walls of the foyer were paneled in the same dark mahogany as the floors, and the house smelled of polish and potpourri. There was an ornate birdcage elevator to the left of the door, just beside the stairs. Benedict led Lennon past the elevator and down a narrow hall. As they walked, the floors groaned beneath their feet, in what seemed like a begrudging welcome.

The walls of the foyer were paneled in the same dark mahogany as the floors, and the house smelled of polish and potpourri. There was an ornate birdcage elevator to the left of the door, just beside the stairs. Benedict led Lennon past the elevator and down a narrow hall. As they walked, the floors groaned beneath their feet, in what seemed like a begrudging welcome.

Benedict led her past the kitchen and through the parlor to a little study off the back of the house, with a wall of windows and French doors opening out onto a small, sun-washed solarium. The study was covered in a grid of shadows cast from the window stiles and bars.

Benedict gestured to a large oak desk. There were two chairs drawn up on either side. Benedict sat in one and Lennon sat in the other.

Benedict led her past the kitchen and through the parlor to a little study off the back of the house, with a wall of windows and French doors opening out onto a small, sun-washed solarium. The study was covered in a grid of shadows cast from the window stiles and bars. Benedict gestured to a large oak desk. There were two chairs drawn up on either side. Benedict sat in one and Lennon sat in the other.

“I suppose I should tell you about Drayton,” said Benedict, and his eyes took on the faraway look of someone moved by memory. “I graduated years ago. You might’ve been just a fluttering in your mother’s womb back then. Maybe less than that, even. Little more than an egg and an idea.”

“I suppose I should tell you about Drayton,” said Benedict, and his eyes took on the faraway look of someone moved by memory. “I graduated years ago. You might’ve been just a fluttering in your mother’s womb back then. Maybe less than that, even. Little more than an egg and an idea.”

Benedict’s eyes came back into focus, and he blinked quickly, like he was only just remembering that Lennon was sitting there. “Tell me, what do you know of Drayton?”

Benedict’s eyes came back into focus, and he blinked quickly, like he was only just remembering that Lennon was sitting there. “Tell me, what do you know of Drayton?”

“Nothing. I’ve never heard of it. I didn’t even apply.”

“Nothing. I’ve never heard of it. I didn’t even apply.”

“Of course you did. Everyone’s applied, whether they know it or not.”

“Of course you did. Everyone’s applied, whether they know it or not.”

“But how is that possible? Don’t I need to present a portfolio or take some sort of exam?”

“But how is that possible? Don’t I need to present a portfolio or take some sort of exam?”

“You’re already taking it. The fi rst phase of testing begins at birth.”

“You’re already taking it. The fi rst phase of testing begins at birth.”

“And the second?” Lennon asked, pressing for more.

“And the second?” Lennon asked, pressing for more.

“This interview.”

“This interview.”

“And the third?”

“And the third?”

“The entry exam, but you shouldn’t worry about that,” said Benedict, looking mildly irritated. “Candidates always have so many questions when they come here, but most don’t make it past the interview. Besides, there’s little I can say to ease your curiosity. Drayton is to be experienced not explained. All I can tell you is that Drayton is an institution devoted to the study of the human condition. At least, that’s what they put on the pamphlets they passed out at my orientation. Perhaps its ethos has changed since then. It’s been many years.” Benedict stood up, one of his knees popping loudly. “Before we begin, let me make you something to eat.”

“The entry exam, but you shouldn’t worry about that,” said Benedict, looking mildly irritated. “Candidates always have so many questions when they come here, but most don’t make it past the interview. Besides, there’s little I can say to ease your curiosity. Drayton is to be experienced not explained. All I can tell you is that Drayton is an institution devoted to the study of the human condition. At least, that’s what they put on the pamphlets they passed out at my orientation. Perhaps its ethos has changed since then. It’s been many years.” Benedict stood up, one of his knees popping loudly. “Before we begin, let me make you something to eat.”

“I’m not hungry.”

“I’m not hungry.”

“And yet you must eat,” he said, waving her off. “You can’t interview on an empty stomach. Besides, you’ll need it for the pain.”

“And yet you must eat,” he said, waving her off. “You can’t interview on an empty stomach. Besides, you’ll need it for the pain.”

“I’m not in any pain.”

“I’m not in any pain.”

“It’ll come,” said Benedict, and a sharp chill slit down her spine like the blade of a razor. Lennon wondered, shift ing uncomfortably in her chair, if she was entirely safe in this strange house with this strange man who was supposed to be from Drayton. What if this was all some elaborate sex-trafficking scheme wherein the targets were “gift ed and talented” kids who’d never received their magic school acceptance letters and grew up to become depressed, praise-starved, thoroughly gullible adults.

“It’ll come,” said Benedict, and a sharp chill slit down her spine like the blade of a razor. Lennon wondered, shift ing uncomfortably in her chair, if she was entirely safe in this strange house with this strange man who was supposed to be from Drayton. What if this was all some elaborate sex-trafficking scheme wherein the targets were “gift ed and talented” kids who’d never received their magic school acceptance letters and grew up to become depressed, praise-starved, thoroughly gullible adults.

Benedict disappeared down the hall and into the kitchen. There was the clattering of pots and pans, water running and later boiling. Unsure of what to do, Lennon turned her attention to the strange portrait hanging over Benedict’s desk. The lower half of the painting was rendered in hyperrealistic detail, depicting a man dressed in a

Benedict disappeared down the hall and into the kitchen. There was the clattering of pots and pans, water running and later boiling. Unsure of what to do, Lennon turned her attention to the strange portrait hanging over Benedict’s desk. The lower half of the painting was rendered in hyperrealistic detail, depicting a man dressed in a

flesh-colored tweed blazer, and a crisp white shirt buttoned up to the throat. But the upper half of the image was distorted, as if the artist had in a moment of great frustration taken up a wet washcloth and viciously smeared the thick layers of oil paint, as if to wipe the canvas clean. There were stretched and gaping eye sockets, a ruined mouth, the twisted contour of what might have been a nose, but it was hard for Lennon to say.

flesh-colored tweed blazer, and a crisp white shirt buttoned up to the throat. But the upper half of the image was distorted, as if the artist had in a moment of great frustration taken up a wet washcloth and viciously smeared the thick layers of oil paint, as if to wipe the canvas clean. There were stretched and gaping eye sockets, a ruined mouth, the twisted contour of what might have been a nose, but it was hard for Lennon to say.

“A former student painted it for me,” said Benedict. He stood in the doorway, holding a breakfast tray. On it: a delicately folded cloth napkin, a bowl of pasta, a glass of wine, and a small dish stacked with pale cookies.

“A former student painted it for me,” said Benedict. He stood in the doorway, holding a breakfast tray. On it: a delicately folded cloth napkin, a bowl of pasta, a glass of wine, and a small dish stacked with pale cookies.

Glancing at the spread he’d prepared, Lennon realized she must’ve been gazing at that painting longer than she’d realized. “It’s . . . compelling.”

Glancing at the spread he’d prepared, Lennon realized she must’ve been gazing at that painting longer than she’d realized. “It’s . . . compelling.”

“Quite,” said Benedict, and he set the tray down in front of her, taking a seat in the chair beneath the portrait. He nodded to the food. “Go on, then.”

“Quite,” said Benedict, and he set the tray down in front of her, taking a seat in the chair beneath the portrait. He nodded to the food. “Go on, then.”

Lennon ate. The pasta was herbaceous and a little too lemony.

Lennon ate. The pasta was herbaceous and a little too lemony.

“How do you like it?” Benedict inquired.

“How do you like it?” Benedict inquired.

“It’s very good,” said Lennon, chewing mechanically. She hated eating in front of people, and strangers especially, but she didn’t want to appear rude.

“It’s very good,” said Lennon, chewing mechanically. She hated eating in front of people, and strangers especially, but she didn’t want to appear rude.

“You grew up in Brunswick, Georgia,” said Benedict, watching her eat. His eyes were wide and grave. “Yours was the only Black family within your neighborhood, a half-built subdivision that went under in the last recession. The movers you hired warned your parents as a kindness that families like yours didn’t move into neighborhoods like that. Your father was a high school history teacher. He and your mother were both avid bird-watchers. Do you hold these facts to be true?”

“You grew up in Brunswick, Georgia,” said Benedict, watching her eat. His eyes were wide and grave. “Yours was the only Black family within your neighborhood, a half-built subdivision that went under in the last recession. The movers you hired warned your parents as a kindness that families like yours didn’t move into neighborhoods like that. Your father was a high school history teacher. He and your mother were both avid bird-watchers. Do you hold these facts to be true?”

Lennon faltered with the fork raised halfway to her mouth. “How did you know all of this? I don’t understand.”

Lennon faltered with the fork raised halfway to her mouth. “How did you know all of this? I don’t understand.”

“You don’t understand the mechanics of how a person on one side of the world can take a call from someone on the other. But you trust your own ears and you know that it’s true. This is no different. You don’t understand the mechanics of how you came to be here, but it is real, and it is happening, so all you need to do is trust that someone, or something, more informed than you must have made this happen.”

“You don’t understand the mechanics of how a person on one side of the world can take a call from someone on the other. But you trust your own ears and you know that it’s true. This is no different. You don’t understand the mechanics of how you came to be here, but it is real, and it is happening, so all you need to do is trust that someone, or something, more informed than you must have made this happen.”

“So you’re saying this is all some type of magic?”

“So you’re saying this is all some type of magic?”

“May I remind you that I’m the interviewer,” said Benedict, not unkindly, though his tone was rather fi rm. “I ask the questions for now.”

“May I remind you that I’m the interviewer,” said Benedict, not unkindly, though his tone was rather fi rm. “I ask the questions for now.”

Lennon fell silent.

Lennon fell silent.

“When you were young, you would often wake in the morning to see your father standing on the back porch of the house, peering into a pair of binoculars, bird-watching. One day, he spotted a nest of starlings in the branches of an oak tree. What did your father teach you to do to the starlings?”

“When you were young, you would often wake in the morning to see your father standing on the back porch of the house, peering into a pair of binoculars, bird-watching. One day, he spotted a nest of starlings in the branches of an oak tree. What did your father teach you to do to the starlings?”

“I don’t see how these questions relate to my admission.”

“I don’t see how these questions relate to my admission.”

“You’re not meant to. Just answer them as best you can. What did he teach you to do to the starlings, Lennon?”

“You’re not meant to. Just answer them as best you can. What did he teach you to do to the starlings, Lennon?”

“Crush their eggs,” she whispered tonelessly, her cheeks flushed from the shame of it.

“Crush their eggs,” she whispered tonelessly, her cheeks flushed from the shame of it.

“And what about the starlings that had already hatched the little ones huddled in their nests among a graveyard of cracked eggs? What did he teach you to do to them?”

“And what about the starlings that had already hatched the little ones huddled in their nests among a graveyard of cracked eggs? What did he teach you to do to them?”

“He told me to take their heads between thumb and pointer finger, and twist them, fast and hard, the way you’d turn a bottle cap.”

“He told me to take their heads between thumb and pointer finger, and twist them, fast and hard, the way you’d turn a bottle cap.”

“And why did your father tell you to do this?”

“And why did your father tell you to do this?”

“Because . . . because the starlings were a menace to other birds.

“Because . . . because the starlings were a menace to other birds.

They drove them away, stole their nests, and spread disease. He called them vermin and told me that it was imperative to sacrifice a few to save many.”

They drove them away, stole their nests, and spread disease. He called them vermin and told me that it was imperative to sacrifice a few to save many.”

Benedict smiled, and it was an entirely different expression than the one he had welcomed her with at the door. So different, in fact, that Lennon considered the idea that this was the first moment he had been truly genuine. “You walk down a narrow lane. Someone walks toward you from the opposite direction. The path isn’t wide enough to accommodate both of you, standing shoulder to shoulder. Are you the one that steps aside?”

Benedict smiled, and it was an entirely different expression than the one he had welcomed her with at the door. So different, in fact, that Lennon considered the idea that this was the first moment he had been truly genuine. “You walk down a narrow lane. Someone walks toward you from the opposite direction. The path isn’t wide enough to accommodate both of you, standing shoulder to shoulder. Are you the one that steps aside?”

“I I’m not sure.”

“I I’m not sure.”

“This is a yes-or-no question. Are you the one that steps aside, Lennon?”

“This is a yes-or-no question. Are you the one that steps aside, Lennon?”

“Yes.”

“Yes.”

Benedict appeared appeased. He nodded to her engagement ring, an heirloom that had belonged to the dead great-aunt of someone significant on Wyatt’s father’s side of the family. The center stone was nearly two carats, and the band was encrusted with other smaller stones that glittered brilliantly when the sunlight struck them. The fi rst time she’d slipped it on her hand, it felt heavy. “You’re married?”

Benedict appeared appeased. He nodded to her engagement ring, an heirloom that had belonged to the dead great-aunt of someone significant on Wyatt’s father’s side of the family. The center stone was nearly two carats, and the band was encrusted with other smaller stones that glittered brilliantly when the sunlight struck them. The fi rst time she’d slipped it on her hand, it felt heavy. “You’re married?”

“Not yet,” or likely ever on account of the fact that her fiancé was fucking one of her supposed friends but she didn’t say that last bit out loud. “I got engaged over the winter.”

“Not yet,” or likely ever on account of the fact that her fiancé was fucking one of her supposed friends but she didn’t say that last bit out loud. “I got engaged over the winter.”

“To Wyatt Banks?”

“To Wyatt Banks?”

“Yes.”

“Yes.”

“Tell me more.”

“Tell me more.”

“About Wyatt?”

“About Wyatt?”

Benedict appeared, for a moment, disgusted. He waved her off with a flap of his hands. “We don’t need to waste any more time on that man. I know enough of the sob story pretty little girl leaves her

Benedict appeared, for a moment, disgusted. He waved her off with a flap of his hands. “We don’t need to waste any more time on that man. I know enough of the sob story pretty little girl leaves her

dreams and aspirations to become a bauble, an accessory to the life of a man she, wrongly, believes is more significant than she is. Does that about sum it up?”