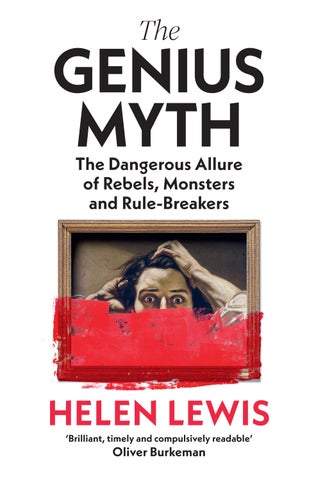

GENIUS MYTH

The Dangerous Allure of Rebels, Monsters and Rule-Breakers

‘Brilliant, timely and compulsively readable’ Oliver Burkeman

Also by Helen l ewis

The Spark

Helen

LO NDO N

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Jonathan Cape, an imprint of Vintage, is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies

Vintage, Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London sw 11 7 bw penguin.co.uk/vintage global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published by Jonathan Cape in 2025

Copyright © Helen Lewis 2025

Helen Lewis has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset in 11.7/ 16pt Calluna by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 y H68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

HB ISBN 9781787333246

TPB ISBN 9781787333253

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

For Rob

‘ “Greatness” may be out of fashion, as is the transcendental, but it is hard to go on living without some hope of encountering the extraordinary.’

Harold Bloom, Genius

The word genius makes me uncomfortable. It carries a secret within it. For a word that is used so frequently and casually, its meaning is hard to pin down. ‘Geniuses are like thunderstorms,’ wrote the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard. ‘They go against the wind, terrify people, cleanse the air.’

That is beautiful prose, but it’s not exactly a definition. Trawl through the works of the great philosophers and you’ll find many observations like that: dazzling but ultimately unhelpful. ‘The man of talent is like a marksman who hits a mark others cannot hit,’ wrote Arthur Schopenhauer in 1818. ‘The man of genius is like a marksman who hits a mark they cannot even see .’ (This is usually rendered on inspirational posters as ‘talent hits the target, genius hits a target others cannot see’.) Immanuel Kant was pithier: genius is ‘talent that gives the rule to art’. What is a genius? A genius is original. A genius is creative. A genius is special. A genius is innately gifted. A genius is different, somehow.

Despite this lack of precision, I bet you that if I asked a thousand people on the street – pretty much anywhere in the

West – to name some geniuses, a few names would recur again and again. * Da Vinci. Einstein. Tolstoy. Shakespeare. Bach. Picasso. (Maybe, these days, Taylor Swift and Elon Musk.) Even without a stable definition, genius exists. And that reveals what is really going on. The people who really matter in this story aren’t the idols and the heroes but the crowd. Us. This book is my attempt to find out why the rest of us need geniuses, and how we bestow the label. You can’t be a genius without followers, fluffers, fans – guardians of the flame.

All of this matters because the secret of genius is the political message smuggled within the word itself. The promotion of a specific person as a genius can be a stealthy argument for what that person represents. A nation’s supremacy, perhaps, or the importance of an idea, or – distastefully – for the notion that men are intellectually superior to women, or Europeans are intellectually superior to Africans. Genius is a right-wing concept, because it champions the individual over the collective. The supportive wives get quietly painted out, the research assistants airbrushed away, the government bailout goes unmentioned, the collaborators downgraded, the university’s role diminished. Because a genius is an individual, we don’t pay enough attention to scenius – a word coined by the musician Brian Eno to describe the ‘ecology of talent’ that nurtures innovation. Think of Florence during the 1500s or Silicon Valley after the Second World War: these were sites of scenius, allowing talented individuals to reach their full potential.

Sometimes, I think of an individual genius like a queen bee, chosen from all the other larvae to be fed royal jelly. But in bees,

* I’ve limited this book to the West – loosely and broadly defined – both because of my own limited ability to read texts from other cultures, and because ‘genius’ has historically been an European (and then American) concept.

there is no genetic difference between a queen and a worker. They are sisters. Every female bee has the potential to become a queen. Do humans do something similar, by deciding whose potential is worth encouraging, whose shortcomings are worth offsetting and whose selfishness is to be indulged? And what are these misshapen figures huddled at the edge of our vision? Here come all the horrors enabled by the concept of genius: the neglected children, the plagiarised assistants, the put-upon wives, the betrayed collaborators, the tantrums and the self-absorption. We feel instinctively that greatness must have a price. (Perhaps we need this idea to explain why we aren’t geniuses.) Sometimes that price is paid by its possessor. More often, the suffering is borne by the people around the genius.

So am I sharpening my axe to destroy the concept altogether? No, of course not. Because we all hunger to experience the transcendent, the extraordinary, the inexplicable. And that is what geniuses offer us. ‘Once you saw phoenixes,’ writes Ralph Waldo Emerson in his 1841 essay Uses of Great Men. 1 ‘They are gone; the world is not therefore disenchanted.’ Instead of animals that burst into flame, we have people who burn a little more brightly than those around them.

The ancient Greeks had a word, deinos, that meant both wonderful and terrible – awesome in its original sense. The conservative philosopher Edmund Burke, writing around the time of the French Revolution, created a division between the ‘sublime’ and the ‘beautiful’. Anyone could appreciate the easy beauty of a waterfall or a watercolour, but he felt that we needed another category for objects or events that were ‘productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling’. Encountering genius can feel like that, I think – that vertiginous falling away as you contemplate an artwork, or an equation, or a new concept . . . and have no idea how it was created by a human brain. Haven’t

you felt it, looking at Van Gogh’s almond blossom, or counting up the words Shakespeare gifted us, or listening to Mozart, or looking down at the earth from an aeroplane window, realising that tonnes of metal and flesh are resting on nothing but air? How did the Wright brothers do it – how did they know to do it?

The science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke once wrote that any ‘sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic’. This is how genius appears to us, too. One day we lived in a world where no one knew about gravity. The next day we did. The air had been cleansed. Genius doesn’t exist. And yet it does.

Now, I’m not such an iconoclast that I’m going to argue that talent doesn’t matter – if you gave me a thousand years and the best teachers in the world I could still never paint like Monet or make a breakthrough in quantum physics. But something else is going on when an individual is anointed as a genius. For a start, that person is now assigned to a special category, somewhere between secular saint and superhero – and the reflected glow burnishes all their other achievements and opinions. (This is particularly troublesome when so many geniuses have also done and said extremely dumb, hurtful or discriminatory things.) As an onlooker, bestowing the word turns a subjective assessment – ‘I like this’ – into something that masquerades as objective fact. A natural phenomenon. An unavoidable, immutable truth.

Oh, and one other thing – since so many talented people are weird, genius becomes a licensing scheme for their eccentricities. Genius transmutes odd into special.

Using ‘genius’ to mean a special sort of person is an evolution of the world’s original meaning. In Greek and Roman times, the word meant a visiting spirit – you weren’t a genius, but one might speak through you. Socrates talked about the daimonion that guided him (a word that is the ancestor of our ‘demon’, but

without the explicit connotation of evil). A poet was, in Plato’s words, a ‘light, winged, holy thing’. For Romans, inspiration might come from furor divinus (divine fury) or furor poeticus (possession by a poetic muse). They gave us the word genius, which means something between ‘creator’, ‘guardian spirit’ and ‘soul’. The same Latin root gives us ‘genital’ and ‘ingenious’. Some authors argued that certain types of people were more likely to possess genius (unsurprisingly, these were men rather than women, and Roman citizens rather than slaves) but the word had not yet acquired its individualistic modern overtones. In the Jewish and then Christian tradition, meanwhile, creation belonged to God – and usurping his power was unwise.

But then in the Renaissance, the idea of ‘great men’ took hold, in the form of artists and sculptors. By the time of the Romantics in the eighteenth century, this new sense had taken over: a genius went from something a person had to something a person was. He (and it usually is a he)* appears to defy the laws of physics, creating something out of nothing. Let there be light, or general relativity, or penicillin, or Guernica. A genius is a performer of magic. A genius suffers. A genius is disbelieved. A genius is cursed and lucky, all at once. Above all, a genius is a protagonist. A genius makes things happen.

The Oxford English Dictionary records the transition: in 1729, Benjamin Franklin could write that ‘Different Men have Genius’s adapted to Variety of different Arts’ but by 1806, the novelist Henry Siddons was describing one of his characters as ‘a gooddispositioned, industrious boy, but no genius’. That switch matters, because it feeds the dark side of the genius myth: the

* Schopenhauer wrote in On Women : ‘Only the male intellect, clouded by sexual impulse, could call the undersized, narrow-shouldered, broad-hipped, and shortlegged sex the fair sex.’

idea of special people, a class above the rest. And it sets us up to be disappointed – how did this thing I love come from this person I deplore?

This book starts off by tracing this shift, through the first biographies of great men, on to the birth of the ‘tortured genius’ in the 1700s, and then into the IQ obsession of the late nineteenth century. If this book had an alternative title, it would be Special People. This is what I find poisonous about the idea of the genius – that people who succeed wildly in one domain stop thinking of themselves as any combination of talented, lucky and hardworking, and instead come to imagine that they are a superior sort of human. If you’ve ever watched a supposed ‘public intellectual’ express a political opinion so basic and uninformed it makes your teeth ache – perhaps one unknowingly formed in the crucible of their own limited personal experience – you will know what I mean.

On which point, a brief and uncharacteristic moment of personal humility by me. The focus in the following pages is undeniably eclectic, led by my own interests and knowledge (or rather, lack of knowledge). There are gaps in my brain, and this is an undoubtedly idiosyncratic book as a result. I’m more comfortable writing about artists and scientists than musicians and athletes, so my examples skew towards the former.

We will spend a lot of time on the development of IQ testing, and its effects and legacy, because this is the perfect distillation of the ‘special people’ thesis. Does someone with an IQ of 140 necessarily have better, more informed opinions on X or Y than someone with an IQ of 139? Clearly not. The precision is spurious and misleading. Can the social worth of human beings be neatly ranked by their ability to rotate shapes or find analogies? No. But something about IQ encourages these faulty ways of thinking. It can’t be a coincidence that the political tendencies that most

champion IQ online are dominated by people with the exact type of abilities that IQ tests reward.

The second section looks at some of the individual genius myths, and how they are sustained – whether by the estates of great artists or the biopic industry. I’ll also take a step back from the portrait of the genius and see what’s just outside the frame: the support staff, if you will. One of the shocks here will be that you don’t even need to achieve great success to benefit from the genius myth – like the avant-garde director Chris Goode, it can be enough simply to fall into one of its pre-made patterns.

And finally, I want to look at the dominant model of genius today – the tech genius, the Prometheus, the innovator, the savant who can’t make small talk but could dream in algorithms. I believe that Elon Musk is the reincarnation of Thomas Edison – not in a spooky way, but in the sense that their fame tells the same story about the culture that created it. Edison was called the Wizard of Menlo Park, and reporters besieged him to seek his views on God and the future of humanity. Musk talks grandly about dying on Mars (between endless posts on his own social media service) and believes that he can run a government better than any bureaucrat. Both have moved (or moved themselves) into that category of ‘special person’.

But first, let’s understand that geniuses do not just happen. No matter how talented a person is, to be accepted as a genius, they need a story to be woven around them. A genius myth. Consider, for example, the greatest English writer of them all: William Shakespeare.

‘He thinks too much. Such men are dangerous.’

Julius Caesar, Act 1, Scene 2

How did Shakespeare become Shakespeare? It’s not a trick question. When William Shakespeare died in 1616, at the age of fifty-two, he was a popular (and populist) playwright. But he was not an icon in the sense we would recognise – known to everyone, pored over by scholars, on the lips of every successor in his field. Today, there are specialised Shakespeare companies all over the world, including one – based at the Globe on London’s South Bank – that tries to recreate the original performances as authentically as possible. The English town of Stratford-upon-Avon has become a shrine to his memory: you can visit two houses where he lived, as well as his wife’s cottage, even though the man himself spent his working life in London.

All this acclaim is deserved, in my opinion. If anyone can be called a genius, it is William Shakespeare. He was a brilliant innovator, a fountain of creativity, a writer with an extraordinary gift for coining new words and phrases. I bet that in the last week you have heard or used a phrase that was gifted to us by Shakespeare. Perhaps you were ‘eaten out of house and home’ (Henry IV , Part 2 ), or fell victim to the ‘green-eyed monster’ (Othello ). Shakespeare gave his characters an inner life that must have been awe- inspiring to audiences raised on passion plays and

other religious pageants. In Hamlet, perhaps his greatest play, he gave us a puzzling protagonist and an ambiguous text that still prompts debate among directors and actors.

Shakespeare deserves his place in history, then. But still – how did he get there? Plenty of talented writers and artists are briefly fashionable without receiving the kind of veneration given to Shakespeare across the centuries. What separates Shakespeare from the rest is that a group of people worked to preserve his memory and celebrate his achievements. Seven years after his death, two of his fellow actors, John Heminges and Henry Condell, put together the ‘first folio’ of his plays. Both men were personal friends of Shakespeare, and he remembered them both in his will. In the Folio, they declared that they wanted to ‘keepe the memory of so worthy a friend and fellow worker alive as was our Shakespeare’.

Their devotion is our great good luck: without the First Folio, eighteen of the plays – including The Tempest and Macbeth – would have been lost. That Shakespeare’s legacy came so close to annihilation is revealing. Today, plays such as King John and Double Falsehood are scoured for any trace of the great man’s input. Back then, it took two personal friends of Shakespeare to preserve his canon. For the first half of the seventeenth century, although Shakespeare was admired, he was not generally seen as the undisputed star among his contemporaries, let alone the greatest writer in the English language.

So what changed? The rise and fall of Puritanism helped. When theatres reopened in England after the Civil War and the reign of the Cromwells, the entrepreneurs who ran them had a problem. They didn’t have enough newly commissioned plays to meet popular demand. So they turned to the old favourites – like Shakespeare – rewritten and restaged to suit the new mood. One of those impresarios was William Davenant, who liked

to encourage speculation that he was Shakespeare’s illegitimate son. Davenant loved spectacle, and he approached the texts with exactly zero reverence. He decided to have the witches in Macbeth ‘whizzing through the air’.1 He restructured the plots. He cut out the unfunny ‘funny’ bits. He renamed Measure for Measure to make it clear that romance was involved – it became The Law Against Lovers – and even rewrote lines that he felt needed punching up. (Macbeth’s ‘screw your courage to the sticking place’ became ‘bring but your courage to the fatal place’.)

Davenant also produced what one modern critic called ‘a memorably ghastly Restoration version of The Tempest ’.2 Caliban got a sister. Ariel zipped around on a wire, and the whole thing was topped off with an orchestra and a ballet company.

Today, this sort of thing prompts strong letters to the newspapers about disrespecting a national icon. But the carefree Restoration attitude to Shakespeare kept his work alive – as did the later changes, such as the infamous seventeenth-century decision to give King Lear a happy ending. Shakespeare’s plays survived precisely because they were not treated like the best china, brought out with kid gloves, to be admired on high days and holidays. They were raw clay, to be moulded into whatever audiences wanted to see.

But there was a problem. Who wrote all this great stuff, anyway? Audiences wanted to know. They weren’t content with appreciating the work. They wanted to idolise the man, too.

In 1709, long after anyone who had known Shakespeare personally was dead, Nicholas Rowe produced a forty-page account of his life. This remained the standard text for a century, but it was sketchy and light on details. In the centuries since, more has been discovered, but nowhere near enough to satisfy demand. The absence of biographical data has driven some Shakespeare enthusiasts mad – they want the plays to have been written

instead by a knowable aristocrat such as the Earl of Oxford, or a woman. The belief that Shakespeare didn’t write Shakespeare’s plays is surprisingly widespread, taking in everyone from the actor Derek Jacobi to the Supreme Court judge Sandra Day O’Connor, via Sigmund Freud and Malcolm X. The deaf lind writer Helen Keller thought Francis Bacon wrote them.

At the other extreme, some Shakespeare fanatics have fallen prey to ‘bardolatry’, the practice of treating every object and place related to Shakespeare with the reverence of a medieval Catholic towards a fragment of the true Cross. If you want to mark the moment that Shakespeare had geniusdom thrust upon him, then look to a single year: 1769. That was when the actor David Garrick staged a Jubilee Festival in Stratford to celebrate the author’s memory. The three-day extravaganza was completely absurd. There were verses addressed to ‘Avonian Willy’. Stratford residents charged visitors to use their loos. And an extraordinary range of merch went on sale, from handkerchiefs to ribbons.3 Relics from the mulberry tree in Shakespeare’s garden were particularly popular; they were made into everything from toothpicks to inkhorns.

The only thing missing from all this was . . . Shakespeare. None of his plays were performed at the jubilee. Instead, attendees were treated to Garrick delivering an ode to the writer, set to music by the same composer who gave us ‘Rule, Britannia’. ‘It is no wonder that he should endeavour to make a god of Shakespear since he has usurped the office of his High-priest; and has already gained money enough by it, to make a golden calf,’ wrote Garrick’s contemporary Charles Macklin.4 That’s one good reason to anoint a genius: you can siphon off some of the money and acclaim for yourself. At the same time, England gained a national poet – Shakespeare was the greatest writer of all time, and naturally, he wrote in English, the greatest language in the world.

And once established in England, bardolatry could be exported elsewhere. Shakespeare’s works travelled to America and to the outposts of the British Empire. During Britain’s imperial phase, the worship of Shakespeare carried an argument smuggled within it: how could a small, damp country in the North Sea claim such importance in the world? Because it was the land of Shakespeare. And Shakespeare himself knew England’s worth: this ‘jewel set in a silver sea’. Shakespeare might have started out writing for the groundlings, but he ended up working for the Warwickshire Tourist Board.

If Shakespeare has bardolatry, then Albert Einstein has ‘priests’ who guard his legacy – and who prevented the existence of his first child being revealed until 1986, nearly thirty years after his death. Pablo Picasso’s heirs are still scrapping over the spoils of his estate. ‘The word “genius”, which experts on Picasso love to use, annoys me and makes me indignant,’ his granddaughter Marina once wrote.5 ‘The Picasso name – the name I bear – has become a trademark. It’s in the windows of perfume and jewellery shops, on ashtrays, ties and T-shirts. You can’t turn on the television without seeing a robot airbrushing the signature Picasso on the side of a car.’ (This is not an exaggeration: in the 1990s, the Picasso estate licensed his name to the French carmaker Citroën.) During his lifetime, Picasso was aware that everything he touched had value. Marina recalls him making paper animals for her as a child, but then refusing to let her take them home: ‘They’re the work of Picasso.’

A genius can be used to sell books, or cars, or toys, or really any kind of crap. When Einstein died in 1955, he left his copyright to Hebrew University in Jerusalem, and in the 1980s, the institution began to license his image rights too; the university has now earned an estimated $250 million from doing so. Einstein was a

genius, but he’s also big business. In the 2000s, Disney licensed the name from the estate for $2.66 million to create ‘Baby Einstein’ toys designed to make your kid smarter. A programme to encourage African intellectuals is called the ‘Next Einstein Forum’. An actor styled as Einstein recently popped up in a Super Bowl commercial to plug the phone company Verizon. In Britain, Einstein’s image is used to sell ‘smart’ electricity meters. Having a shorthand for ‘clever person’ is working out well for companies who want to flatter their customers or embellish their products.

Today, the word genius has been utterly devalued by its use as a branding tool. When my latest Apple purchase mysteriously ceases to work after three years, as it usually does, I take it to the Genius Bar, where an earnest hipster in a roll-neck can diagnose the problem. The web address Genius.com takes me to a lyrics site where I can find out whether Taylor Swift really is singing about being a sexy baby (she is). The Genius Brand is a supplements company, which sells ‘nootropic supplements offer[ing] a safe, natural way to unlock the inner Genius each of us has.*’ (The asterisk leads to a disclaimer noting that the products ‘are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease’.)

So the idea of genius is ambient. But what about the individual cases? What is the process by which a playwright from the Midlands becomes England’s national writer – or a stateless physicist becomes shorthand for ‘smart’? Here’s my argument. Because there is no objective definition of genius – and there never can be – societies anoint exceptional people as geniuses to demonstrate what they value. We call some people ‘special’ to demonstrate what we find special. And in turn, we give those special people latitude that is not extended to ordinary mortals. We have a set of stories about what geniuses are, and how they work, and how singular their achievements are – stories that are often entirely untrue.

This book is called The Genius Myth not to imply that genius doesn’t exist, but to explore those stories as a form of mythmaking. ‘A person’s right to be considered a “genius” by posterity is influenced by quite irrelevant factors,’ wrote the psychologist Hans Eysenck, a troublesome character to whom we will return later, in his book Genius. ‘He is more likely to be called a “genius” if he behaves oddly, dies young or very old, has episodes of madness, is psychopathic in his relations with others, disregards normal restrictions, and generally lives up to the stereotype of genius people have in their minds.’

To put it another way: why is Elon Musk better known than Tim Berners-Lee ? As I am writing this, Elon Musk is unavoidable: he runs a dozen companies, and uses one of them, X, to blast his thoughts out into the world on an hourly basis. He is the subject of a biography by Walter Isaacson, who previously wrote about Leonardo da Vinci, Benjamin Franklin, Albert Einstein and Steve Jobs. (Isaacson convinced Jobs to grant him access by pointing out the company he would be in. You have to assume the same trick worked on Musk.) At every turn, Musk has sought out opportunities to self-mythologise, and he is now one of the leading candidates for our modern idea of a genius. Yet Tim Berners-Lee is the more original thinker, and his breakthrough in creating the World Wide Web has been more important. Every internet-era innovation, from smartphones to Chat GPT , rests on there being an internet at all. (There’s a picture that does the rounds every so often, of Berners-Lee speaking on a news programme, where he is described as ‘web developer’. The joke is that it makes him sound like a hobbyist reskinning WordPress templates, whereas he is literally the man who developed the concept of World Wide Web.) Without Tim Berners-Lee, there would have been no Twitter for Elon Musk to ruin.

Now, Berners- Lee has no shortage of recognition – a

knighthood, numerous advisory board positions, a fellowship at Oxford University – and he is widely celebrated within his own field. But he lives a quiet life, has not tried to make himself upsettingly rich and has never broken through into public consciousness in the way that Elon Musk has.

Here’s one way to understand the difference between the two men, and it’s key to the argument of this whole book. BernersLee describes his work like this:

Most of the technology involved in the web, like the hypertext, like the Internet, multifont text objects, had all been designed already. I just had to put them together. It was a step of generalising, going to a higher level of abstraction, thinking about all the documentation systems out there as being possibly part of a larger imaginary documentation system.6

Did your eye begin to skim that passage? Go on, admit it. They did. Berners-Lee is self-deprecating and technical, whereas Elon Musk does things like change the Twitter press office autoresponse to a poop emoji or insist that he will die on Mars. Elon Musk fires rockets into space, builds fast cars and tells people to leave his company if they are not ‘extremely hardcore’. (More on that later.) He performs the cultural role of genius with apparent enthusiasm: saying odd and provocative things, espousing extreme work habits, maintaining an unusual personal life, drawing attention to himself with salty tweets. Love him or hate him, we can’t stop talking about him.

Let me put it another way. Elon Musk has more than a dozen children, with names like X AE A-Xii and Exa Dark Sideræl. Tim Berners-Lee’s children are called Alice and Ben.

We want great achievements to have been accomplished by unusual people – something about it feels cosmically just. And

we hunger to know the details of their lives: their sleep patterns, their love lives, the moment that inspiration struck. We want to marvel at greatness, but we also want to wallow in gossip. And one man realised that long before everyone else. Let’s meet him next.

‘Jealousy is the tribute mediocrity pays to genius.’

Fulton J. Sheen, attributed

Giorgio Vasari was a good artist. The Medicis employed him as a sculptor and architect. He designed the loggia for the Uffizi in Florence, part of his grand project of establishing the city as an artistic centre.* He designed cupolas and painted Madonnas, built corridors and sculpted saints. Had he lived in another age, he might be remembered as one of its most successful artists. But you have to feel a little bit sorry for Vasari, because he lived through one of the greatest flourishings of art and culture that the world has ever seen. The Renaissance.

As it happens, we have Vasari to thank for the word itself. He became the chronicler of this exceptional period of European history, which he called the rinascita (rebirth) of the classical tradition, after centuries of stagnation. This was the era of Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael, Donatello. † As these artists revived the arts of painting, sculpture and architecture, Vasari revived the Ancient Greek practice of hagiography, or ‘writing about holy ones’. His lasting achievement is a book published in two editions,

* Perhaps you don’t know, as I didn’t, that ‘Uffizi’ translates as ‘offices’.

† And other artists who weren’t also Ninja Turtles, although those are always the ones who spring to mind.

which was called The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. You can trace many well-known stories about artists of the era to Vasari: Brunelleschi and the egg, Michelangelo’s revolting boots, or the tale of how Verrocchio quit painting after being outstripped by his teenage pupil Leonardo da Vinci.

Vasari was born in 1511, in Arezzo, near Florence – and his work often tips into pro-Tuscan propaganda. His Lives promotes Leonardo and Michelangelo, and their work in the region, and deprecates Titian, born at the foot of the Alps and working in Venice. (Vasari did this even though he and Titian were friends.) The narratives created by Vasari, and the hierarchy he championed, persists today. ‘The way you think of art is largely due to Vasari, whether or not you realise it, and whether or not you’ve actually read his book,’ his biographers claim. 1 Until Vasari came along, most biographers recorded the lives of aristocrats. He broke with tradition by focusing on artists, who were ‘manual workers with a spotty education and intensive technical training: by conventional standards, the meanness of their hardscrabble, hardworking lives could hold no interest for aristocratic writers and readers’. * Vasari wanted the project to be democratic: he wrote in the Tuscan dialect – an everyday language – rather than the more elite Latin. He wanted it to be comprehensive: its first word is ‘Adam’ and the last is ‘death’. And he was always fascinated by innovation: we hear about Michelangelo designing his own scaffold to paint the Sistine Chapel, and the breakthrough that allowed sculptors to work in a dense stone called porphyry.

Surprisingly, given the exclusion of female artists from the

* Many of the artists themselves were illiterate. Even Leonardo da Vinci, one of the greatest polymaths of all time, owned only 116 books, according to the Codex he kept.

canon in the subsequent centuries, Vasari featured several women, including the Anguissola sisters and Properzia de’ Rossi. Sofonisba Anguissola was one of the most successful artists of the era, serving as a tutor to the Spanish queen Elisabeth of Valois, and court painter to Philip II , before eventually dying at the age of ninety-three. But she is now largely forgotten.

The one female artist of the Renaissance who is remembered was born too late for Vasari to include: Artemisia Gentileschi, who has recently been the subject of exhibitions, plays and movies. Gentileschi’s reputation has prospered in the twenty-first century because she comes with a readymade feminist legend: she was raped by her father’s apprentice, and testified against him in court – risking her artists’ hands under the thumbscrews to prove she was telling the truth. (Afterwards, she supposedly used her rapist’s face as the model for Holofernes, whose head is cut off by the biblical heroine Judith.) I love Gentileschi’s paintings, which have a sinuous softness to them and an exquisite use of light. Her Judith is also really hacking at Holofernes’ neck – this is no delicate maiden afraid to get her hands bloody, but a steadygripped butcher. But there is no denying that the story of her rape has become central to her mythology: she is now the heroine for every slighted woman. We love a bittersweet genius story, and hers is that she turned a sexual assault into great art. Sofonisba Anguissola’s life and work cannot be reduced to a parable like this, and so she has not been reclaimed and promoted in the same way.

Vasari would have recognised this process, because he was an inveterate myth-maker. In fact, the whole project of acclaiming geniuses is rather like painting a portrait: an entire life and personality is honed down to key details. The idea that artists should be judged on their political appeal seems unfair, but it is an undeniable part of the story of genius. Biographies become

morality tales. And that tendency is due in a large part to Vasari. He pioneered the idea of life-writing as a fable, following in the tradition of Aesop and Ovid, where the particulars of a story are employed to illustrate a theme.

Take the famous story of the Florentine architect Filippo Brunelleschi, which Vasari tells in his Lives. Artists have gathered from across Europe to discuss how to build a dome on the cathedral at the centre of Florence. There are many problems: the weight of the cupola, the lack of support from pillars at the side, the difficulty of building a framework. But Brunelleschi tells the city consuls that he has an answer to all these problems. They laugh at him.

Brunelleschi becomes angry, and rants about all the other problems the wardens haven’t even considered, before being carried out by stewards. He doesn’t even show them his plan. Then he proposes a test to demonstrate who has the ability to build the cupola: whoever can make an egg stand upright on the marble floor should get the job. All the other artists try to balance the egg on its end, and fail.

Then they passed it to Filippo, who lightly took it, broke the end with a blow on the marble and made it stand. All the artists cried out that they could have done as much themselves, but Filippo answered laughing that they would also know how to vault the cupola after they had seen his model and design.2

This is a parable about trust – and about elitism. Brunelleschi was arrogant, unwilling to submit his designs to swine who couldn’t appreciate them. His arrogance was justified, however, because he could hit a target others could not see. The mythological point of the story is that bureaucrats and second-raters shouldn’t

question a genius. Their job is to accept his superior knowledge, and acquiesce.

Vasari’s Lives included serious artistic criticism and authoritative lists of great works. But from the start, what readers loved was the gossip and the personalities. Who wouldn’t want to hear about impassioned rivalries and brave men arguing with the Pope?

His great hero was Michelangelo, whom he describes as being of middle height, thin, with white-flecked black hair – and utterly devoted to art. Vasari’s Michelangelo didn’t care much about food or wine. He sometimes slept in his clothes. He wore his dogleather boots for so long that when he eventually took them off, his skin came off too. And he was a prodigy, once redrawing his tutor Domenico’s outline of a woman: ‘The difference between the two styles is as marvellous as the audacity of the youth whose good judgement led him to correct his master.’ 3 (Remember: special allowances must be made for a genius, even if he is rude or arrogant.)

Vasari turns Michelangelo’s life into a morality tale. He only gets to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling because his rival Bramante knows that the Pope prefers sculptures to paintings. So Bramante recommends Michelangelo, a talented sculptor, for a job that will see him tied up for years holding a paintbrush. (The moral being that squalid motives rebound on you.) The bittersweetness regularly found in genius myths comes from the discomfort that Michelangelo sufferers from painting above his head, tiring his muscles and injuring his eyesight. Vasari then adds, somewhat bathetically, ‘I suffered similarly when doing the vaulting of four large rooms in the palace of Duke Cosimo.’ 4 Nonetheless, the result is extraordinary – and Michelangelo is hailed as il divino – the divine one. The closeness of genius and God is evident to onlookers.

Michelangelo, then, is portrayed by Vasari a single-minded art monk. What about his contemporary Leonardo da Vinci? In Lives, he becomes another archetype of genius: the scatterbrained polymath.

The young Leonardo was beautiful, ‘marvellous and divine,’ writes Vasari, and ‘would have made great profit in learning had he not been so capricious and fickle, for he began to learn many things and then gave them up.’5 Like Michelangelo, Leonardo is a prodigy who quickly outstrips his teacher, Andrea del Verrocchio. Soon after, Leonardo’s father Piero asks him to paint something on wood to give to one of his tenant- farmers, and the young man studies ‘lizards, newts, maggots, snakes, butterflies, locusts, bats and other animals of the kind, out of which he composed a horrible and terrible monster’. When his father asks to see the painting, still not knowing its subject, Leonardo arranges it on an easel and beckons his father into the room. ‘Ser Piero, taken unaware, started back, not thinking of the round piece of wood, or that the face which he saw was painted.’ 6 (The pupil who outdoes the master, and the painter whose talent creates freakishly realistic figures, are two of Vasari’s favourite narratives.)

Recounting Leonardo’s death, the biographer returns to his theme of wasted potential. When the King of France arrives to pay him a visit, Leonardo ‘sat up in bed from respect, and related the circumstances of his sickness, showing how greatly he had offended God and man in not having worked in his art as he ought’.7 He then suffers a ‘paroxysm’ and dies in the king’s arms ‘in the seventy-fifth year of his age’. The entire narrative is unlikely – there is no contemporary record of these events – but the point is to create a bittersweet legend of Leonardo’s quicksilver brain. ‘Thus, by his many surpassing gifts, even though he talked much more about his works than he actually achieved, his name and fame will never be extinguished.’