Lara Prescott was named after the heroine of Doctor Zhivago and first discovered the true story behind the novel after the CIA declassified ninety-nine documents pertaining to its role in the book’s publication and covert dissemination. She travelled the world – from Moscow and Washington, to London and Paris – in the course of her research, becoming particularly interested in political repression in both the Soviet Union and United States and how, during the Cold War, both countries used literature as a weapon. Lara earned her MFA from the Michener Center for Writers. She lives in Austin, Texas with her husband.

Praise for The Secrets We Kept

‘Prescott uses multiple narrators and viewpoints in her impressive debut … A 20th-century tale of Cold War confrontation … Prescott has written an unusual, stimulating variant on the standard spy thriller.’

Sunday Times

‘Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago sits at the centre of this debut novel about passion, heroism and the power of endurance … Irresistibly charged and vividly imagined, it’s told with a breezy confidence that sets the pages flying.’

Mail on Sunday

‘A gorgeous and romantic feast of a novel anchored by a cast of indelible secretaries.’

New York Times

‘Mixing Mad Men, Carol, The Best of Everything and John le Carré, this addictive debut uses the true story behind the publication of Dr Zhivago to spin a tale of spies, love and betrayal.’ i paper

‘The fascinating tale of how the CIA plotted to smuggle Doctor Zhivago back into Russia drives an enjoyable debut … impressive … has all the ingredients for a spy thriller … A great cast of characters … It is the female characters who carry this adventure, from the pragmatic, loyal, indestructible Olga to the marvellous typists. With their Virginia Slims and Thermoses of turkey noodle soup, they make up a kind of smart, gossipy Greek chorus whose commentary begins and ends the novel … the portrayal of the love between Olga and Pasternak is poignant and convincing … set to be a publishing phenomenon … a thoroughly enjoyable read.’

Guardian

‘Stylish, thrilling, smart, vivid.’

Elizabeth McCracken, author of Bowlaway

‘[A] masterpiece.’

Irish Examiner

‘An astonishing real-life story … The pen portrait of the US capital during that period is seductive … A fascinating story … spy Sally Forrester … is a particularly affecting character … Woven into the narrative intrigue are a number of touching love stories.’

Irish Independent

‘Simply sensational. Lara Prescott is a star in the making. From the gulags of the USSR to the cherry blossom trees of Washington DC, this story grips and refuses to let go.’

Kate Quinn, author of The Alice Network

‘A fascinating true-life tale has been embroidered into a thrilling story that has it all – turbulent historical events, romantic love and very cool spycraft … This captivating novel is so assured that it’s hard to believe it’s a debut – and very easy to see why there’s a huge buzz around it.’

Sunday Mirror

‘If you’ve never read Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago, you’ll want to after reading this stylish debut novel. It’s a fascinating fictionalisation of how the celebrated Russian author’s book came to be published … Prescott delivers a multi-layered tale of the drama behind the story.’

Woman & Home

‘A gripping read … inspired by the incredible true story of how the manuscript of Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago, banned in the Soviet Union, had to be smuggled back into the country by the CIA.’

‘Set at the height of the Cold War … This is a panoramic novel about one important skirmish in the battle between the Soviet Union and the free world that defined the second half of the 20th century. Two very different love stories are woven into the action and plenty of impossible moral choices have to be made by its appealing characters.’

Literary Review

‘Full of mystery and intrigue.’

Stellar Magazine

‘Epic in scope, deliciously meaty, and utterly convincing.’

Ben Fountain, author of Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk

‘Prescott delivers a fascinating fictionalisation of how Boris Pasternak’s celebrated book came to publication … In this stylish and confident debut, we delve into the story behind the story, which is just as enthralling.’

Woman’s Weekly

‘Lara Prescott adds a feminist twist to the real-life story of the CIA plot to use Dr Zhivago, banned in the Soviet Union, as anti-communist propaganda at the height of the Cold War.’

Metro

‘Enthralling … This is the rare page-turner with prose that’s as wily as its plot.’

‘Prescott crafts a cloak-and-dagger story of passion, espionage, and propaganda.’

Wall Street Journal

‘No mere spy thriller, the novel draws the reader into the emotional lives of the characters and their ever-changing roles and personas, and questions not only what is banned in the East, but also in the West.’

Scotsman

‘A fascinating fictionalisation of how Doctor Zhivago was published … Part spy thriller and part fiction, Prescott intricately weaves a multi-layered tale out of the novel’s origins.’

Woman

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Windmill Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW

penguin.co.uk

First published in the US by Knopf 2019

First published in the UK by Hutchinson 2019

First published in paperback by Windmill Books 2020 001

Copyright © Lara Prescott, 2019

The moral right of the author has been asserted

This is a work of fiction. Names and characters are the product of the author’s imagination and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Set in 11.03/14.54pt Sabon LT Std Typeset by Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd, Pondicherry

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978–1–786–09074–4

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

“I want to be with those who know secret things or else alone.”

— Rainer Maria Rilke

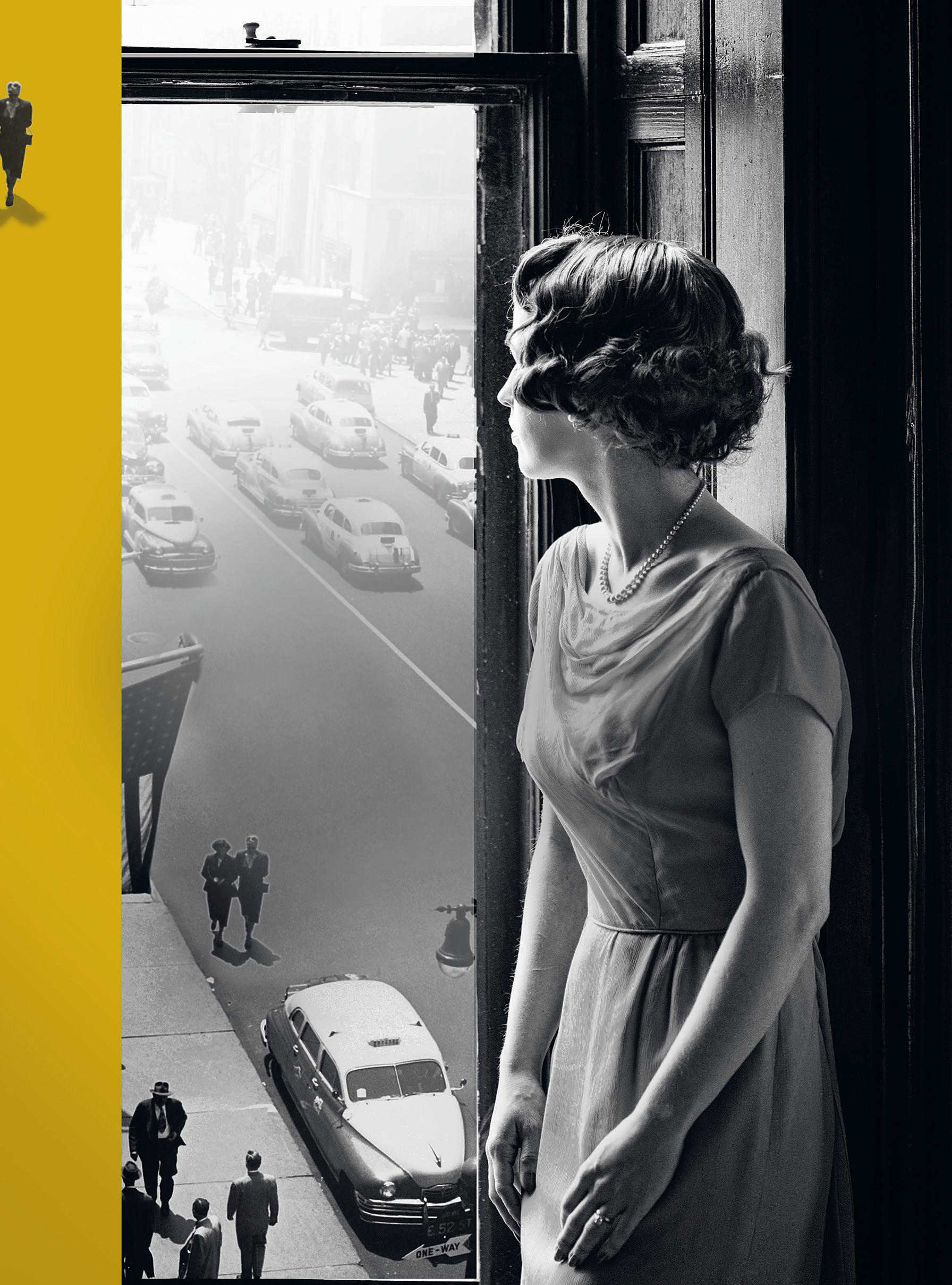

We typed a hundred words per minute and never missed a syllable. Our identical desks were each equipped with a mint- shelled Royal Quiet Deluxe typewriter, a black Western Electric rotary phone, and a stack of yellow steno pads. Our fingers flew across the keys. Our clacking was constant. We’d pause only to answer the phone or to take a drag of a cigarette; some of us managed to master both without missing a beat.

The men would arrive around ten. One by one, they’d pull us into their offices. We’d sit in small chairs pushed into the corners while they’d sit behind their large mahogany desks or pace the carpet while speaking to the ceiling. We’d listen. We’d record. We were their audience of one for their memos, reports, write-ups, lunch orders. Sometimes they’d forget we were there

lara prescott

lara prescott

and we’d learn much more: who was trying to box out whom, who was making a power play, who was having an affair, who was in and who was out.

Sometimes they’d refer to us not by name but by hair color or body type: Blondie, Red, Tits. We had our secret names for them, too: Grabber, Coffee Breath, Teeth. They would call us girls, but we were not.

We came to the Agency by way of Radcliffe, Vassar, Smith. We were the first daughters of our families to earn degrees. Some of us spoke Mandarin. Some could fly planes. Some of us could handle a Colt 1873 better than John Wayne. But all we were asked when interviewed was “Can you type?”

It’s been said that the typewriter was built for women—that to truly make the keys sing requires the feminine touch, that our narrow fingers are suited for the device, that while men lay claim to cars and bombs and rockets, the typewriter is a machine of our own.

Well, we don’t know about all that. But what we will say is that as we typed, our fingers became extensions of our brains, with no delay between the words coming out of their mouths—words they told us not to remember—and our keys slapping ink onto paper. And when you think about it like that, about the mechanics of it all, it’s almost poetic. Almost.

But did we aspire to tension headaches and sore wrists and bad posture? Is it what we dreamed of in high school, when studying twice as hard as the boys? Was clerical work what we had in mind when opening

xiv xvi

the secrets we kept

the fat manila envelopes containing our college acceptance letters? Or where we thought we’d be headed as we sat in those white wooden chairs on the fifty-yard line, capped and gowned, receiving the rolled parchments that promised we were qualified to do so much more?

Most of us viewed the job in the typing pool as temporary. We wouldn’t admit it aloud—not even to each other—but many of us believed it would be a first rung toward achieving what the men got right out of college: positions as officers; our own offices with lamps that gave off a flattering light, plush rugs, wooden desks; our own typists taking down our dictation. We thought of it as a beginning, not an end, despite what we’d been told all our lives.

Other women came to the Agency not to start their careers but to round them out. Leftovers from the OSS, where they’d been legends during the war, they’d become relics relegated to the typing pool or the records department or some desk in some corner with nothing to do. There was Betty. During the war, she ran black ops, striking blows at opposition morale by planting newspaper articles and dropping propaganda flyers from airplanes. We’d heard she once provided dynamite to a man who blew up a resource train as it passed over a bridge somewhere in Burma. We could never be sure what was true and what wasn’t; those old OSS records had a way of disappearing. But what we did know was that at the Agency, Betty sat at a desk along with the

the secrets we kept xv xvii

lara prescott

lara prescott

rest of us, the Ivy League men who were her peers during the war having become her bosses.

We think of Virginia, sitting at a similar desk—her thick yellow cardigan wrapped around her shoulders no matter the season, a pencil stuck in the bun atop her head. We think of her one fuzzy blue slipper underneath her desk—no need for the other, her left leg amputated after a childhood hunting accident. She’d named her prosthetic leg Cuthbert, and if she had too many drinks, she’d take it off and hand it to you. Virginia rarely spoke of her time in the OSS, and if you hadn’t heard the secondhand stories about her spy days you’d think she was just another aging government gal. But we’d heard the stories. Like the time she disguised herself as a milkmaid and led a herd of cows and two French Resistance fighters to the border. How the Gestapo had called her one of the most dangerous of the allied spies—Cuthbert and all. Sometimes Virginia would pass us in the hall, or we’d share an elevator with her, or we’d see her waiting for the number sixteen bus at the corner of E and Twenty-First. We’d want to stop and ask her about her days fighting the Nazis—about whether she still thought of those days while sitting at that desk waiting for the next war, or for someone to tell her to go home.

They’d tried to push the OSS gals out for years—they had no use for them in their new cold war. Those same fingers that once pulled triggers had become better suited for the typewriter, it seemed.

xvi xviii

the secrets we kept

the secrets we kept

But who were we to complain? It was a good job, and we were lucky to have it. And it was certainly more exciting than most government gigs. Department of Agriculture? Interior? Could you imagine?

The Soviet Russia Division, or SR, became our home away from home. And just as the Agency was known as a boys’ club, we formed our own group. We began thinking of ourselves as the Pool, and we were stronger for it.

Plus, the commute wasn’t bad. We’d take buses or streetcars in bad weather and walk on nice days. Most of us lived in the neighborhoods bordering downtown: Georgetown, Dupont, Cleveland Park, Cathedral Heights. We lived alone in walk-up studios so small one could practically lie down and touch one wall with her head and the other with her toes. We lived in the last remaining boarding houses on Mass. Avenue, with lines of bunk beds and ten-thirty curfews. We often had roommates—other government gals with names like Agnes or Peg who were always leaving their pink foam curlers in the sink or peanut butter stuck to the back of the butter knife or used sanitary napkins improperly wrapped in the small wastebasket next to the sink.

Only Linda Murphy was married back then, and only just married. The marrieds never stayed long. Some stuck it out until they got pregnant, but usually as soon as an engagement ring was slipped on, they’d plan their departure. We’d eat Safeway sheet cake in the break room to see them off. The men would come in for a slice and

lara prescott

lara prescott

say they were awfully sad to see them go; but we’d catch that glimmer in their eye as they thought about whichever newer, younger girl might take their place. We’d promise to keep in touch, but after the wedding and the baby, they’d settle down in the farthest corners of the District—places one would have to take a taxi or two buses to reach, like Bethesda or Fairfax or Alexandria. Maybe we’d make the journey out there for the baby’s first birthday, but anything after that was unlikely.

Most of us were single, putting our career first, a choice we’d repeatedly have to tell our parents was not a political statement. Sure, they were proud when we graduated from college, but with each passing year spent making careers instead of babies, they grew increasingly confused about our state of husbandlessness and our rather odd decision to live in a city built on a swamp. And sure, in summer, Washington’s humidity was thick as a wet blanket, the mosquitoes tiger-striped and fierce. In the morning, our curls, done up the night before, would deflate as soon as we’d step outside. And the streetcars and buses felt like saunas but smelled like rotten sponges. Apart from a cold shower, there was never a moment when one felt less than sweaty and disheveled. Winter didn’t offer much reprieve. We’d bundle up and rush from our bus stop with our head down to avoid the winds that blew off the icy Potomac.

But in the fall, the city came alive. The trees along Connecticut Avenue looked like falling orange and red fireworks. And the temperature was lovely, no need to

the secrets we kept

the secrets we kept

worry about our blouses being soaked through at the armpits. The hot dog vendors would serve fire-roasted chestnuts in small paper bags—the perfect amount for an evening walk home.

And each spring brought cherry blossoms and busloads of tourists who would walk the monuments and, not heeding the many signs, pluck the pink-and-white flowers and tuck them behind an ear or into a suit pocket.

Fall and spring in the District were times to linger, and in those moments we’d stop and sit on a bench or take a detour around the Reflecting Pool. Sure, inside the Agency’s E Street complex the fluorescent lights cast everything in a harsh glow, exaggerating the shine on our forehead and the pores on our nose. But when we’d leave for the day and the cool air would hit our bare arms, when we’d choose to take the long walk home through the Mall, it was in those moments that the city on a swamp became a postcard.

But we also remember the sore fingers and the aching wrists and the endless memos and reports and dictations. We typed so much, some of us even dreamed of typing. Even years later, men we shared our beds with would remark that our fingers would sometimes twitch in our sleep. We remember looking at the clock every five minutes on Friday afternoons. We remember the paper cuts, the scratchy toilet paper, the way the lobby’s hardwood floors smelled of Murphy Oil Soap on Monday mornings and how our heels would skid across them for days after they were waxed.

xix xxi

lara prescott

lara prescott

We remember the one strip of windows lining the far end of SR—how they were too high to see out of, how all we could see anyway was the gray State Department building across the street, which looked exactly like our gray building. We’d speculate about their typing pool. What did they look like? What were their lives like? Did they ever look out their windows at our gray building and wonder about us?

At the time, those days felt so long and specific; but thinking back, they all blend. We can’t tell you whether the Christmas party when Walter Anderson spilled red wine all over the front of his shirt and passed out at reception with a note pinned to his lapel that read do not resuscitate happened in ’51 or ’55. Nor do we remember if Holly Falcon was fired because she let a visiting officer take nude photos of her in the second-floor conference room, or if she was promoted because of those very photos and fired shortly after for some other reason.

But there are other things we do remember.

If you were to come to Headquarters and see a woman in a smart green tweed suit following a man into his office or a woman wearing red heels and a matching angora sweater at reception, you might’ve assumed these women were typists or secretaries; and you would’ve been right. But you would have also been wrong. Secretary: a person entrusted with a secret. From the Latin secretus, secretum. We all typed, but some of us did more. We spoke no word of the work we did after we covered our typewriters each day. Unlike some of the men, we could keep our secrets.

1949–1950

1949–1950

When the men in black suits came, my daughter offered them tea. The men accepted, polite as invited guests. But when they began emptying my desk drawers onto the floor, pulling books off the shelf by the armful, flipping mattresses, riffling through closets, Ira took the whistling kettle off the stove and put the teacups and saucers back in the cupboard.

When one man carrying a large crate ordered the other men to box up anything useful, my youngest, Mitya, went onto the balcony, where he kept his hedgehog. He swaddled her inside his sweater, as if the men would box up his pet too. One of the men—the one who would later let his hand slide down my backside while putting me into their black car—put his hand atop Mitya’s head and called him a good boy. Mitya, gentle Mitya, pushed the man’s hand off in one violent

lara prescott

movement and retreated into the bedroom he shared with his sister.

My mother, who’d been in the bath when the men arrived, emerged wearing just a robe—her hair still wet, her face flushed. “I told you this would happen. I told you they would come.” The men ransacked my letters from Boris, my notes, food lists, newspaper clippings, magazines, books. “I told you he would bring us nothing but pain, Olga.”

Before I could respond, one of the men took hold of my arm—more like a lover than someone sent to arrest me—and, with his breath hot against my neck, said it was time to go. I froze. It took the howls of my children to snap me back into the moment. The door shut behind us, but their howls grew louder still.

The car made two left turns, then a right. Then another right. I didn’t have to look out the window to know where the men in black suits were taking me. I felt sick, and told the man next to me, who smelled like fried onions and cabbage. He opened the window—a small kindness. But the nausea persisted, and when the big yellow brick building came into view, I gagged.

As a child, I was taught to hold my breath and clear my thoughts when walking past Lubyanka—it was said the Ministry for State Security could tell if you harbored anti-Soviet thoughts. At the time, I had no idea what anti-Soviet thoughts were.

The car went through a roundabout and then the gate into Lubyanka’s inner courtyard. My mouth filled

the secrets we kept

with bile, which I quickly swallowed. The men seated next to me moved away as far as they could.

The car stopped. “What’s the tallest building in Moscow?” the man who smelled like onions and cabbage asked, opening the door. I felt another wave of nausea and bent forward, emptying my breakfast of fried eggs onto the cobblestones, just missing the man’s dull black shoes. “Lubyanka, of course. They say you can see all the way to Siberia from the basement.”

The second man laughed and put out his cigarette on the bottom of his shoe.

I spat twice and wiped my mouth with the back of my hand.

Once inside their big yellow brick building, the men in black suits handed me off to two female guards, but not before giving me a look that said I should be grateful they weren’t the ones taking me all the way to my cell. The larger woman, with a faint mustache, sat in a blue plastic chair in the corner while the smaller woman asked me, in a voice so soft it was as if coaxing a toddler onto the toilet, to remove my clothing. I removed my jacket, dress, and shoes and stood in my flesh-colored underwear while the smaller woman took off my wristwatch and rings. She dropped them into a metal container with a clank that echoed against the concrete walls and motioned for me to undo my brassiere. I balked, crossing my arms.

lara prescott

“We need it,” the woman in the blue chair said—her first words to me. “You might hang yourself.” I unclasped my bra and removed it, the cold air hitting my chest. I felt their eyes scan my body. Even in such circumstances, women appraise each other.

“Are you pregnant?” the larger woman asked.

“Yes,” I answered. It was the first time I’d acknowledged this aloud.

The last time Boris and I had made love was a week after he’d broken things off with me for the third time. “It’s over,” he’d told me. “It has to end.” I was destroying his family. I was the cause of his pain. He’d told me all this as we walked down an alley off the Arbat, and I fell into a bakery’s doorway. He went to pick me up, and I screamed for him to leave me be. People stopped and stared.

The next week, he was at my front door. He’d brought a gift: a luxurious Japanese dressing gown his sisters had procured for him in London. “Try it on for me,” he implored. I ducked behind my dressing screen and slipped it on. The fabric was stiff and unflattering, billowing out at my stomach. It was too big—maybe he’d told his sisters the gift was for his wife. I hated it and told him so. He laughed. “Take it off, then,” he pleaded. And I did.

A month later, my skin began tingling, as if submerging into a hot bath after coming in from the cold. I’d felt that tingle before, with Ira and Mitya, and knew I was carrying his child.

“A doctor will visit you soon, then,” the smaller guard said.

the secrets we kept

They searched me, took everything, gave me a big gray smock and slippers two sizes too big, and escorted me to a cement box containing only a mat and a bucket.

I was kept in the cement box for three days and given kasha and sour milk twice daily. A doctor came to check on me, though only to confirm what I already knew. I owed the baby growing inside me for preventing the more terrible things I’d heard happened to women in that box.

After the three days, they moved me to a large room, also cement, with fourteen other female prisoners. I was given a bed with a metal frame screwed into the floor. As soon as the guards closed the door, I lay down.

“You can’t sleep now,” said a young woman sitting on the adjacent bed. She had thin arms with sores on her elbows. “They’ll come and wake you.” She pointed to the fluorescent lights glaring above. “Sleeping is not allowed during the day.”

“And you’ll be lucky if you get an hour of sleep at night,” a second woman said. She slightly resembled the first woman but looked old enough to be her mother. I wondered if they were related—or if after being in this place, under those bright lights, wearing the same clothes, everyone eventually resembled each other. “That’s when they come get you for their little talks.”

The younger woman gave the older woman a look.

“What do we do instead of sleep?” I asked. “We wait.”

lara prescott

“And play chess.”

“Chess?”

“Yes,” said a third woman, who was sitting at a table across the room. She held up a knight fashioned from a thimble. “Do you play?” I didn’t, but I would learn over the next month of waiting.

The guards did come. Each night, they’d pull one woman out at a time and return her to Cell No. 7 hours later, red-eyed and silent. I steeled myself each night to be taken but was still surprised when they finally did come.

I was awoken with the tap of a wooden truncheon against my bare shoulder. “Initials!” spat the guard hovering over my bed. The men who came at night always demanded our initials before taking us away. I mumbled a reply. The guard told me to get dressed, and he didn’t look away while I did.

We walked the length of a dark hallway and down several flights of stairs. I wondered if the rumors were true: that Lubyanka went twenty floors below ground and connected to the Kremlin by tunnels, and that one tunnel went to a bunker equipped with every luxury, built for Stalin during the war.

I was led to the end of another hall, to a door marked 271. The guard opened it a crack, peeked in, then flung it open with a laugh. It wasn’t a cell, but a storage room stocked with towers of canned meats and neatly stacked boxes of tea and sacks of rye flour. The guard grunted and pointed across the room to another door, this one

with no number. I opened it. Inside, my eyes had trouble adjusting to the light. It was an office with posh furnishings that wouldn’t be out of place in a hotel lobby. A wall of bookshelves packed with leather-bound books lined one wall; three guards lined another. A man wearing a military tunic was sitting at the large desk at the center of the room. On his desk were stacks of books and letters: my books, my letters.

“Have a seat, Olga Vsevolodovna,” he said. The man had the rounded shoulders of someone who’d spent a lifetime behind a desk or bent over in hard labor; by his perfectly manicured hands wrapped around his teacup, I guessed the former. I sat in the small chair in front of him.

“Sorry to keep you waiting,” he said. I started in with the speech I’d had weeks to prepare: “I have done nothing wrong. You must release me. I have a family. There is no—”

He held up a finger. “Nothing wrong? We will determine that . . . in time.” He sighed and picked at his teeth with the tip of his thick, yellowed thumbnail. “And it will take time.”

I’d thought they’d let me out any day, that all would be resolved, that I would spend New Year’s Eve sitting next to a warm stove toasting with a nice glass of Georgian wine with Boris.

“So what have you done?” He shuffled through some papers and held up what appeared to be a warrant. “Expressing anti-Soviet opinions of a terroristic nature,”

he read, as if reading a list of ingredients in a honey cake recipe.

One might think terror runs cold—that it numbs the body, a preparation for incoming harm. For me, it was a hotness that burned like fire traveling from one end to the other. “Please,” I said, “I need to speak to my family.”

“Allow me to introduce myself.” He smiled and leaned back in his chair, the leather creaking. “I am your humble interrogator. Can I offer you some tea?”

“Yes.”

He made no move to fetch me tea. “My name is Anatoli Sergeyevich Semionov.”

“Anatoli Sergeyevich—”

“You may address me as Anatoli. We’ll be getting to know each other quite well, Olga.”

“You may address me as Olga Vsevolodovna.”

“That is fine.”

“And I’d like you to be direct with me, Anatoli Sergeyevich.”

“And I’d like you to be honest with me, Olga Vsevolodovna.” He pulled out a stained handkerchief from his pocket and blew his nose. “Tell me about this novel he’s been writing. I’ve heard things.”

“Such as?”

“Tell me,” he said. “What is this Doctor Zhivago about?”

“I don’t know.”

“You don’t know?”

“He’s still writing it.”

“Suppose I left you here alone for a while, with a little piece of paper and a pen—maybe you could think about what you do or don’t know about the book and write it all down. Is that a good plan?”

I didn’t respond.

He stood and handed me a stack of blank paper. He pulled a gold-plated pen from his pocket. “Here, use my pen.”

He left me with his pen and his paper and his three guards.

Dear Anatoli Sergeyevich Semionov, Do I even address this as a letter? How does one properly address a confession?

I do have something to confess, but it is not what you want to hear. And with such a confession, where does one even begin? Perhaps at the beginning?

I put the pen down.

The first time I saw Boris, he was at a reading. He stood behind a simple wooden lectern, a spotlight glinting off his silver hair, a shine on his high forehead. As he read his poetry, his eyes were wide, his expressions big and childlike, radiating out across the audience like waves, even up to my seat in the balcony. His hands had moved rapidly, as if directing an orchestra. And in a way, he had been. Sometimes the audience couldn’t hold back and yelled out his lines before he could finish. Once, Boris had paused and looked up into the lights, the secrets we kept

lara prescott

and I swore he could see me watching from the balcony—that my gaze cut through the white lights to meet his. When he finished, I stood—my hands clasped together, forgetting to clap. I watched as people rushed the staged and engulfed him, and I remained standing as my row, then the balcony, then the entire auditorium emptied.

I picked up the pen.

Or should I begin with how it began?

Less than a week after that poetry reading, Boris stood on the thick red carpet in Novy Mir’s lobby, chatting with the literary magazine’s new editor, Konstantin Mikhailovich Simonov, a man with a closet full of prewar suits and two ruby signet rings that clinked against each other when he smoked his pipe. It was not uncommon for writers to visit the office. In fact, I was often charged with giving the tour, offering them tea, taking them to lunch—the normal courtesies. But Boris Leonidovich Pasternak was Russia’s most famous living poet, so Konstantin had played the host, walking him down the long row of desks, introducing him to the copywriters, designers, translators, and other important staff. Close up, Boris was even more attractive than he had been on stage. He was fifty-six but could’ve passed for forty. His eyes darted between people as he exchanged pleasantries, his high cheekbones exaggerated by his broad smile.

As they neared my desk, I grabbed the translation I’d been working on earlier that morning and began marking up the poetry manuscript at random. Under my desk, I wiggled my stockinged feet into my heels.

“I’d like to introduce you to one of your most ardent admirers,” Konstantin said to Boris. “Olga Vsevolodovna Ivinskaya.”

I extended my hand.

Boris turned my wrist over to kiss the back of my hand. “Pleasure to meet you.”

“I’ve loved your poems since I was a girl,” I’d said, stupidly, as he pulled away.

He smiled, exposing the gap between his teeth. “I’m actually working on a novel now.”

“What is it about?” I asked, cursing myself for asking a writer to explain his project before he was finished.

“It’s about the old Moscow. One you’re much too young to remember.”

“How very exciting,” Konstantin said. “Speaking of which, we should chat in my office.”

“I’ll hope to see you again then, Olga Vsevolodovna,” Boris said. “How nice I still have admirers.”

It went from there.

The first time I agreed to meet him, I was late and he was early. He said he didn’t mind, that he’d gotten to Pushkinskaya Square an hour early and had enjoyed watching one pigeon after the next take their place atop Pushkin’s bronze statue, like breathing, feathered hats. When I sat next to him on the bench, he took my hand

lara prescott

and said he hadn’t thought of anything else since meeting me—that he couldn’t stop thinking about how it would feel to see me approach and sit down next to him, how it would feel to take my hand.

Every morning after, he’d wait outside my apartment. Before work, we’d walk the wide boulevards, through squares and parks, back and forth across every bridge that crossed the Moskva, never with any destination in mind. The lime trees had been in full bloom that summer, and the entire city smelled honey sweet and slightly rotten.

I’d told him everything: of my first husband, whom I’d found hanging in our apartment; of my second, who’d died in my arms; of the men I’d been with before them, and the men I’d been with after. I spoke of my shames, my humiliations. I spoke of my hidden joys: being the first person off a train, arranging my face creams and perfumes so their labels faced forward, the taste of sour cherry pie for breakfast. Those first few months, I talked and talked and Boris listened.

By summer’s end, I began calling him Borya and he began calling me Olya. And people had begun to talk about us—my mother the most. “It’s simply unacceptable,” she’d said so many times I lost count. “He’s a married man, Olga.”

But I knew Anatoli Sergeyevich did not care to hear that confession. I knew what confession he wanted me to write. I remembered his words: “Pasternak’s fate will

secrets we kept

depend on how truthful you are.” I picked up the pen and began again.

Dear Anatoli Sergeyevich Semionov, Doctor Zhivago is about a doctor.

It’s an account of the years between the two wars.

It’s about Yuri and Lara.

It’s about the old Moscow.

It’s about the old Russia.

It’s about love.

It’s about us.

Doctor Zhivago is not anti-Soviet.

When Semionov returned an hour later, I handed him my letter. He scanned it, turning it over. “You can try again tomorrow night.” He crushed the paper into a ball, dropped it, and waved at the guards to take me away. —

Night after night, a guard would come for me, and Semionov and I would have our little chats. And night after night, my humble interrogator would ask the same questions: What is the novel about? Why is he writing it? Why are you protecting him?

I didn’t tell him what he wanted to hear: that the novel was critical of the revolution. That Boris had rejected socialist realism in favor of writing characters the secrets we kept

lara prescott

who lived and loved by their hearts’ intent, independent of the State’s influence.

I didn’t tell him that Borya had begun the novel before we met. That Lara was already in his mind—and that in the early pages, his heroine resembled his wife, Zinaida. I didn’t tell him that as time went on, Lara eventually became me. Or maybe I became her.

I didn’t tell him how Borya had called me his muse, how that first year together he said he made more progress on the novel than he had in the previous three years combined. How I’d first been attracted to him because of his name—the name everyone knew—but fell in love with him despite it. How to me, he was more than the famous poet up on the stage, the photograph in the newspaper, the person in the spotlight. How I delighted in his imperfections: the gap in his teeth; the twenty-year-old comb he refused to replace; the way he scratched his cheek with a pen when thinking, leaving a streak of black ink across his face; the way he pushed himself to write his great work no matter the cost.

And he did push himself. By day he’d write at a furious pace, letting the filled pages fall into a wicker basket under his desk. And at night, he’d read me what he had written.

Sometimes he would read to small gatherings in apartments across Moscow. Friends would sit in chairs arranged in a semicircle around a small table, where Borya sat. I’d sit next to him, feeling proud to play the

the secrets we kept

the secrets we kept

hostess, the woman at his side, the almost wife. He’d read in his excited way, words toppling over each other, and stare just above the heads of those seated before him.

I would attend those readings in the city, but not when he’d read in Peredelkino, a short train ride from Moscow. The dacha in the writers’ colony was his wife’s territory. The reddish-brown wooden house with large bay windows sat atop a sloping hill. Behind it were rows of birch and fir trees, to the side a dirt path leading to a large garden. When he first brought me there, Borya took his time explaining which vegetables had thrived over the years, which had failed, and why.

The dacha, larger than most citizens’ regular homes, was provided to him by the government. In fact, the entire colony of Peredelkino was a gift from Stalin himself, to help the Motherland’s handpicked writers flourish. “The production of souls is more important than the production of tanks,” he’d said.

As Borya said, it was also a fine way to keep track of them. The author Konstantin Aleksandrovich Fedin lived next door. Korney Ivanovich Chukovsky lived nearby, using his house to work on his children’s books. The house where Isaac Emmanuilovich Babel lived and was arrested, and to which he never returned, was down the hill.

And I didn’t say a word to Semionov about how Borya had confessed to me that what he was writing could be the death of him, how he feared Stalin would

lara prescott

put an end to him as he’d done to so many of his friends during the Purges.

The vague answers I did offer never satisfied my interrogator. He’d give me fresh paper and his pen and tell me to try again.

Semionov tried everything to elicit a confession. Sometimes he was kind, bringing me tea, asking my thoughts on poetry, saying he had always been a fan of Borya’s early work. He arranged for a doctor to see me once a week and instructed the guards to give me an additional woolen blanket.

Other times, he attempted to bait me, saying Borya had tried to turn himself in, in exchange for me. Once, a metal cart rolled down the hallway, knocking into a wall with a bang, and he joked that it was Boris, pounding on the walls of Lubyanka trying to get in.

Or he’d say Boris was spotted at an event, looking fine with his wife on his arm. “Unencumbered” was the word he used. Sometimes it was not his wife, but a pretty young woman. “French, I think.” I’d force myself to smile and say I was glad to hear he was happy and healthy.

Semionov never once laid a hand on me, nor even threatened to. But the violence was always there, his gentle demeanor always calculated. I had known men like him all my life and knew what they were capable of.

the secrets we kept

At night, my cellmates and I tied strips of musty linen around our eyes—a futile attempt to block out the lights that never shut off. Guards came and went. Sleep came and went.

On nights when sleep didn’t come at all, I’d breathe in and out, trying to settle my mind long enough to open a window to the baby growing inside me. I held my hand on my stomach, trying to feel something. Once, I thought I felt something small—as small as a bubble breaking. I held on to that feeling as long as I could.

As my belly grew, I was allowed to lie down an hour longer than the other women. I was also given one extra portion of kasha and the occasional serving of steamed cabbage. My cellmates gave me portions of their food as well.

Eventually, they gave me a bigger smock. My cellmates asked to touch my belly and feel the baby kick. His kicks felt like a promise of a life outside Cell No. 7. Our littlest prisoner, they’d coo.

The night began like the others. I was roused from bed by the poke of a truncheon and escorted to the interrogation room. I sat across from Semionov and was given a fresh sheet of paper.

Then there was a knock at the door. A man with hair so white it almost looked blue entered the room and told Semionov the meeting had been arranged. The man

lara prescott

turned toward me. “You have asked for one, and now you have it.”

“I have?” I asked. “With whom?”

“Pasternak,” Semionov answered, his voice louder and harsher in the other man’s presence. “He’s waiting for you.”

I didn’t believe it. But when they loaded me into the back of a van with no windows, I let myself believe. Or rather, I couldn’t suppress the tiny hope. The thought of seeing him, even under those circumstances, was the most joy I’d felt since our baby’s first kick.

We arrived at another government building and I was led though a series of corridors and down several flights of stairs. By the time we reached a dark room in the basement, I was exhausted and sweaty and couldn’t help but think of Borya seeing me in such an ugly state.

I turned around, taking in the bare room. There were no chairs; there was no table. A lightbulb dangled from the ceiling. The floor sloped toward a rusted drain at its center.

“Where is he?” I asked, immediately realizing how stupid I’d been.

Instead of an answer, my escort suddenly pushed me through a metal door, which locked behind me. The smell assaulted me. It was sweet and unmistakable. Tables holding long forms under canvas came into focus. My knees buckled and I fell to the cold, wet

secrets we kept

secrets we kept

floor. Was Boris under there? Is that why they’d brought me here?

The door opened again, after what could’ve been minutes or hours, and two arms lifted me to my feet. I was dragged back up the stairs, down more seemingly endless corridors.

We boarded a freight elevator at the end of one hall. The guard closed the cage and pulled the lever. Motors came to life and the elevator shook violently but did not move. The guard pulled the lever again and swung the cage open. “I keep forgetting,” he said with a smirk, pushing me out of the elevator. “It’s been out of service for ages.”

He turned to the first door on the left and opened it. Semionov was inside. “We’ve been waiting,” he said.

“Who is we?”

He knocked twice on the wall. The door opened again, and an old man shuffled inside. It took me a moment to realize it was Sergei Nikolayevich Nikiforov, Ira’s former English teacher—or a shadow of him. The normally fastidious teacher’s beard was wiry, his trousers falling off his slight frame, his shoes missing their laces. He reeked of urine.

“Sergei,” I mouthed. But he refused to look at me.

“Shall we begin?” Semionov asked. “Good,” he said without waiting for an answer. “Let’s go over this again. Sergei Nikolayevich Nikiforov, do you confirm the evidence you gave to us yesterday: that you were present during anti-Soviet conversations between Pasternak and Ivinskaya?”

I screamed but was quickly silenced by a slap from the guard standing next to the door. I was knocked against the tiled wall, but I felt nothing.

“Yes,” Nikiforov replied, his head still bowed.

“And that Ivinskaya informed you of her plan to escape abroad with Pasternak?”

“Yes,” Nikiforov said.

“It’s not true!” I cried. The guard lunged toward me.

“And that you listened to anti-Soviet radio broadcasts at the home of Ivinskaya?”

“That’s not . . . actually, no . . . I think—”

“So you lied to us, then?”

“No.” The old man raised his shaky hands to cover his face, letting out an unearthly whine.

I told myself to look away, but didn’t.

After Nikiforov’s confession, they took him away, and me back to Cell No. 7. I’m not sure when the pain began—I had been numb for hours—but at some point, my cellmates alerted the guard that my bedroll was soaked with blood.

I was taken to the Lubyanka hospital and as the doctor told me what I already knew, all I could think of was how my clothes still smelled like the morgue, like death.

“The witnesses’ statements have enabled us to uncover your actions: You have continued to denigrate our lara prescott

the secrets we kept

regime and the Soviet Union. You have listened to Voice of America. You have slandered Soviet writers with patriotic views and have praised to the skies the work of Pasternak, a writer with antiestablishment opinions.”

I listened to the judge’s verdict. I heard his words, and the number he gave. But I didn’t put the two together until I was taken back to my cell. Someone asked, and I answered: “Five years.” And it was only then that it hit me: five years in a reeducation camp in Potma. Five years, six hundred kilometers from Moscow. My daughter and son would be teenagers. My mother would be nearly seventy. Would she still be alive? Boris would have moved on—maybe having found a new muse, a new Lara. Maybe he already had.

The day after my sentencing, they gave me a moth-eaten winter coat and loaded me into the back of a canvastopped truck filled with other women. We watched Moscow stream by through an opening in the back.

At one point, a group of schoolchildren crossed behind the truck, two by two. Their teacher called out for them to keep their eyes straight ahead, but a little boy turned and we made eye contact. For a moment, I imagined he was my own son, my Mitya, or maybe the baby I’d never know.

When the truck stopped, the guards yelled for us to get out and move quickly to the train that would take

lara prescott

us to the Gulag. I thought of the early pages of Borya’s novel, of Yuri Zhivago boarding a train with his young family, seeking safety in the Ural Mountains. The guards sat us on benches in a car without windows, and as the train rolled out, I closed my eyes. Moscow radiates out in circles, like a pebble dropped into still water. The city expands from its red center to its boulevards and monuments to apartment buildings— each one taller and wider than the next. Then come the trees, then the countryside, then snow, then snow.