‘I

was caught up from the first page’

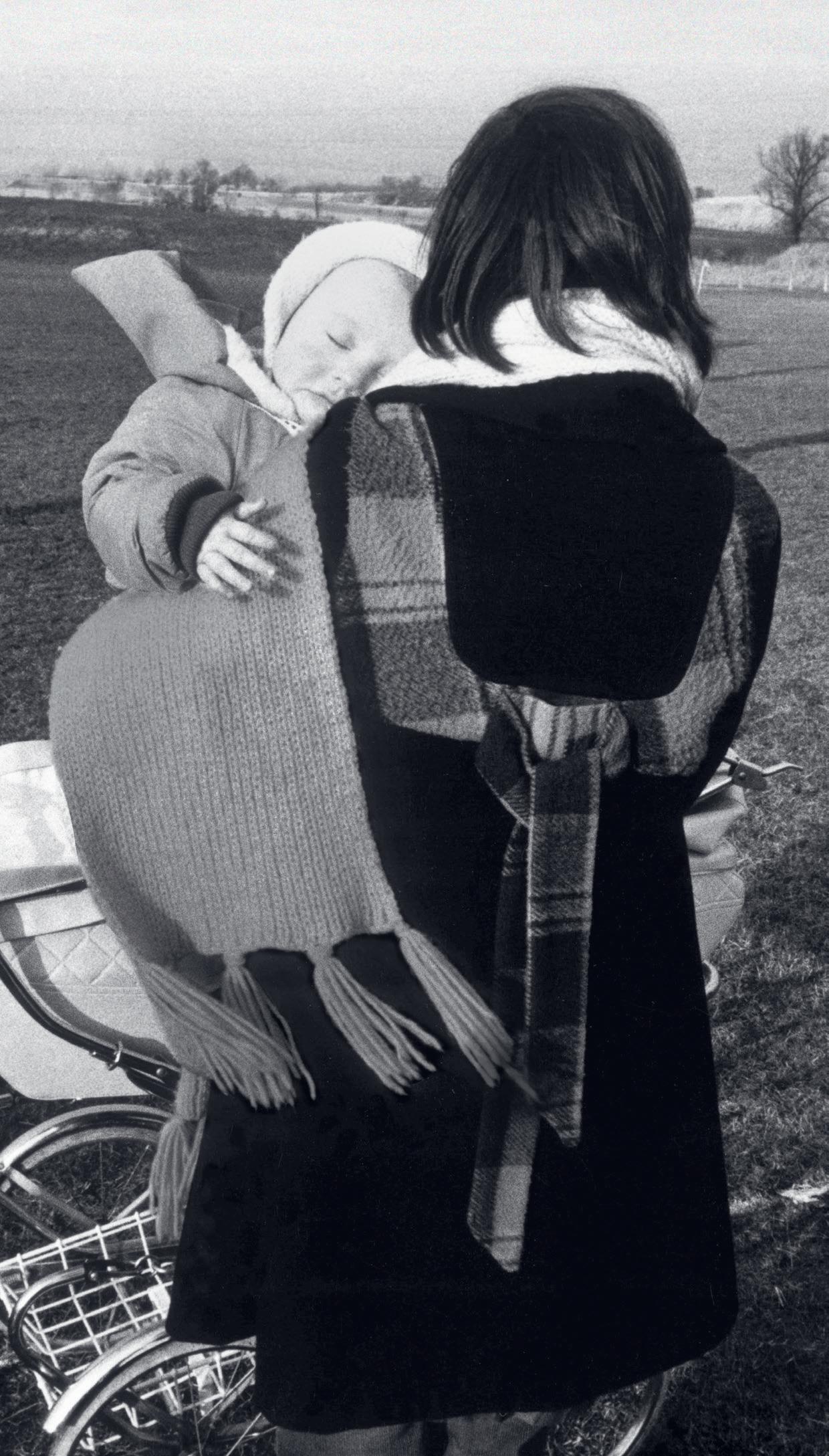

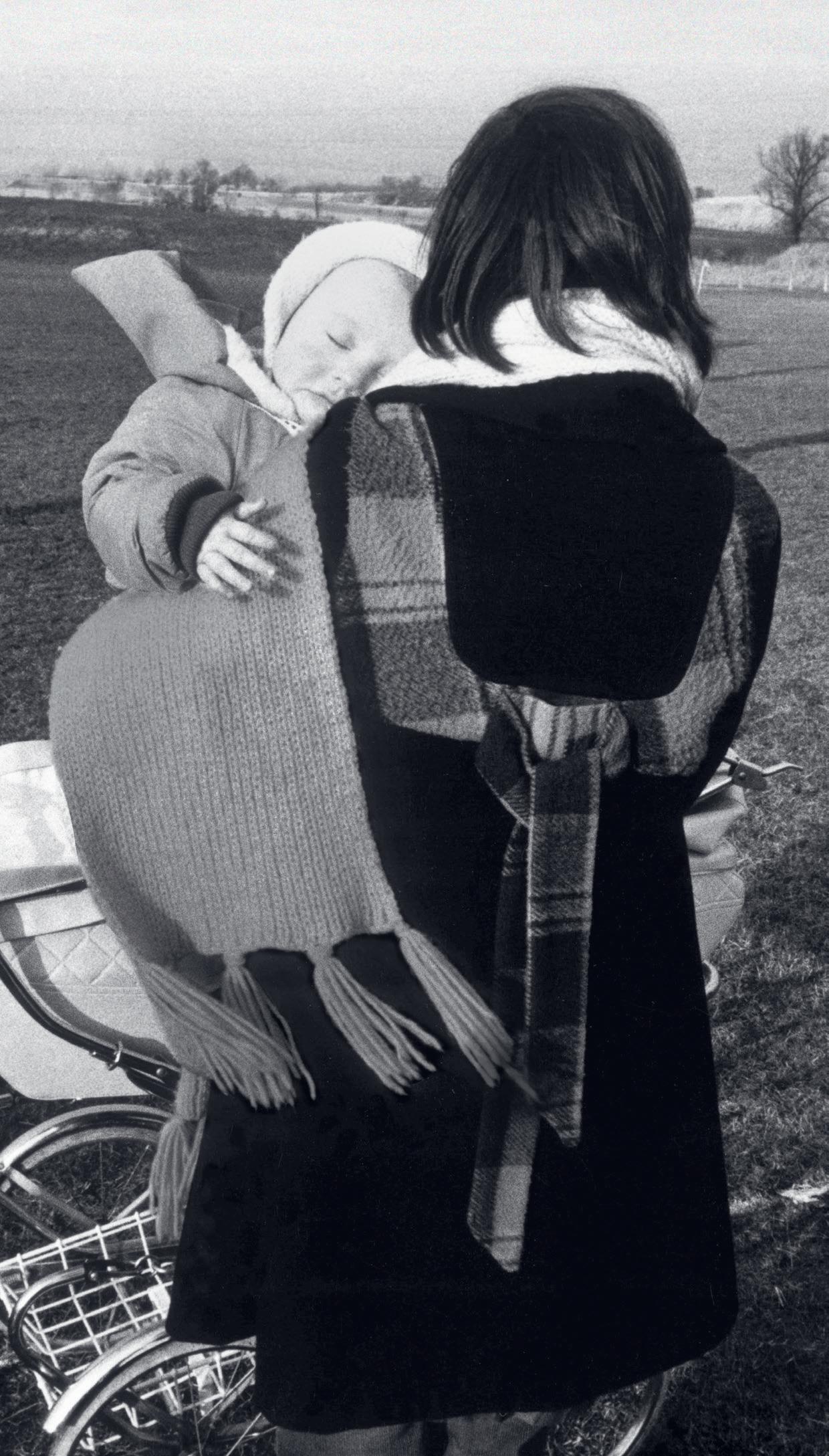

‘Beautiful and tender . . . parental love, prejudice and the things we carry’

‘A

‘I

was caught up from the first page’

‘Beautiful and tender . . . parental love, prejudice and the things we carry’

‘A

‘Every

page sings out with empathy and love, pain and honesty’

wonderful novel . . . absolutely gripping’

l O n DO n

Chatto & Windus, an imprint of Vintage, is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published by Chatto & Windus in 2025

Copyright © Claire Lynch 2025

Claire Lynch has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

‘Peanut Butter’ originally from Not Me by Eileen Myles.

Copyright © 1991 by Eileen Myles. Courtesy of Semiotext(e) Publishers; I Must Be Living Twice/new & selected poems by Eileen Myles.

Copyright © 2015 by Eileen Myles. Courtesy of HarperCollins Publishers

‘What Kind of Times Are These’ © 1995, 2002 by Adrienne Rich, from The Fact of a Doorframe: Selected Poems 1950-2001 by Adrienne Rich, published by W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Used by permission of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

penguin.co.uk/vintage

Typeset in 11.6/15.8pt Calluna by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 yh 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

h B i SB n 9781784745837

t PB i SB n 9781784745844

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

why shouldn’t something I have always known be the very best there is. I love you from my childhood, starting back there when one day was just like the rest, random growth and breezes, constant love, a sandwich in the middle of day

From ‘Peanut Butter’, Eileen Myles, 1991

I’ve walked there picking mushrooms at the edge of dread, but don’t be fooled this isn’t a Russian poem, this is not somewhere else but here, our country moving closer to its own truth and dread, its own ways of making people disappear.

From ‘What Kind of Times Are These’, Adrienne Rich, 1995

To all those who try their best. That is all you can ever do.

Five and a half hours after he found out he was dying, Heron drove to his favourite supermarket. In the absence of an alternative, and because it was a Thursday, he decided to stick to his routine.

It is no secret that Heron likes to do his weekly food shop on a Thursday. In the evening if at all possible, late afternoon at the earliest. His family tease him about it, his strange inflexibilities.

‘Live a little,’ his daughter had said last week, ‘go shopping on a Monday morning, I dare you.’

But Thursdays are quiet and that suits him. Thursdays are sensible. Heron likes to start the weekend with a full fridge, although his weekends are, in truth, much like any other day of the week now.

At the top of the escalator he finds a small trolley, a perfect compromise, he has always thought, since a big trolley is really too much, a basket not quite enough. Heron is an organised shopper, placing each item into the reusable bag he has labelled for its corresponding kitchen cupboard. He keeps the cleaning products separate from the bread. He doesn’t rush, or forget the milk, or squash the salad. Heron isn’t one of those people who minds when they change the layout of the supermarket from time to time. If anything

he sort of enjoys it, the hint of scavenger hunt it gives to tracking down the thin-cut marmalade. He could not say, if asked, why he shops in this particular way, the system speaks for itself.

Heron pushes his small trolley to the furthest, coldest corner of the supermarket. For obvious reasons, frozen foods are always selected last. Today, in a significant break from routine, he slides open the glass lid of a waist-high chest freezer, flattens out the bags of potato smiley faces, and climbs inside.

It is the smell rather than the cold he notices first. Even with the lid slightly open, the air inside the freezer is stale and starchy. He is as surprised as anyone to find it is actually quite comfortable inside a chest freezer, even with the frost starting to soak through at the backs of his knees. Heron adjusts his shoulder blades, stretches out his legs, and the frozen potato faces settle beneath him. He lies still in the muffled peace of the chest freezer, and he lives.

/

Heron had felt sorry for the doctor in a way, a youngish woman, fiddling with her pen despite her best intentions. It can’t be easy to have to say it out loud to someone.

‘There are leaflets. And websites,’ the doctor had said, and then she’d moved, just slightly, reaching out to touch her desk to show him that this part, at least, was over. Heron had stood up too fast, tangling his jacket on the back of the chair, saying, absurdly, ‘It’s showerproof.’

/

And still, it wasn’t as cold as you would think, in the freezer, or maybe it was so cold he couldn’t tell any more, that was a thought.

Heron looks up through the fog on the glass lid. He looks beyond, to the fluorescent lights and steel joists of the supermarket ceiling.

There are things he will have to do now. Things he will have to say. Admit.

He looks at the ice dripping and shining on the inside walls of the freezer beside his head. The manic smiles and hollow eyes of the potato faces. He looks at these things and he is fine. Heron is so fine that he might have simply stayed in the freezer for ever, had a woman not slid open his lid in search of frozen petit pois and screamed.

It takes three members of staff to get him out. He is, as it turns out, quite cold indeed. The back of his head wet, his knees sore and stiffened. The manager is very good about it, cheerful even when he says, ‘Let’s get you out of there, sir, shall we?’ and, ‘Is there someone we can call?’

It is only when he gets home that Heron understands the tone of the manager’s voice. Calm, tolerant, as if a man reclining in a freezer was just something one expects in a varied retail career. Heron understands then what the manager saw. A confused old man. Not quite all there. Not quite all here.

Before bed, Heron calls his daughter on the landline. He doesn’t like to use his mobile in the house.

‘Just me,’ he says, as he always does. Then he pauses, waits for her to say, ‘Hello stranger,’ or ‘Long time no hear,’ as she does, without fail, every night.

When Maggie asks Heron about his day he has plenty to say. He tells her about the young couple across the street, laying a new lawn, as if they haven’t even noticed the hosepipe ban. He tells her, in quite some detail, about an interesting radio documentary on wind farms. Had she caught it?

She hadn’t.

Heron talks and Maggie makes the sounds of listening.

Uh hmm. Yup. ‘Interesting,’ she says, or, ‘Lovely.’

Heron talks, but some things don’t come up. The hospital, for example. The supermarket. Some things are best papered over, Heron thinks. For now. All of that would come out the wrong way, if he tried to explain it. Instead, he sticks to safer topics: the new seed catalogue, which arrived yesterday. The free coffee waiting for him on his loyalty card. Maggie listens, and she waits, for a gap, the chance to escape the conversation with, ‘Well, I’d better let you go. Sleep well.’

Heron lets her take it, a way out for both of them.

‘You too.’

‘Night then. Goodnight.’ /

‘Let’s hear it,’ Conor says. ‘What’s the latest press release from the neighbour’s loft conversion?’

‘Nothing to report,’ Maggie tells her husband. ‘It’s a slow news day.’

She pours two glasses of wine, fridge cold and slightly too full for a Thursday evening. As she hands one to Conor she can see he’s a bit disappointed. Heron’s nightly phone calls are usually a rich seam. She’d heard Conor at a party once, joking with their friends that he knew more about his father- in- law’s greenfly problem than he did about politics in the Middle East. She knew she was supposed to laugh along, see the funny side of Heron’s strangeness. But Maggie hadn’t found it funny. She didn’t mind that her dad told her everything; it had always been like that. All the little details of his day, his current thoughts and theories. Conor couldn’t understand it, or wouldn’t. Instead of laughing, Maggie had said, in front of everyone, ‘Maybe you should try reading the newspapers a bit more carefully, darling,’ and they had driven home from the party in silence.

Glasses empty they lock up the house, feed the cat. Conor gathers up his laptop and charger for work in the morning, saving time. Maggie checks the schedule on the fridge, all the things the children will need tomorrow. Tom’s hockey stick, the packed lunches, a form Olivia needs

Maggie to sign for the school camping trip. There are different things for the next day and the day after that. It is her job to remember the things, even though the children aren’t babies any more, even though Conor is a grown man quite capable of managing harder tasks than reading the carpool rota for himself. Still, she will do it, keep them all moving forward. Keep them all on track.

On the front steps of the church hall, two teenage girls shake a plastic bucket of change, making the coins jump and ring.

‘Twenty pence to come in. Ten for children,’ they shout on sing-song repeat.

Dawn checks her purse. It’s early in the month, so she’s fine, but she needs to make it last. A new salon has opened on the high street and the apprentices will give you a cut and blow-dry for free if you come in after hours. If she does that, she can put her haircut money towards the denim jacket she’s seen in the catalogue.

She can see that the proceeds from the jumble sale are going towards something or other. The church roof? The lepers? She can’t read the label Sellotaped onto the bucket, the carefully felt-tipped bubble writing. ‘It’s for us!’ the Girl Guides say when they see her squinting to read it. ‘We need a new camping stove.’

Dawn recognises one of the girls, she went to school with her big sister, a lifetime ago, five minutes ago. She drops her coins into the bucket and the girls smile their matching metal smiles back at her. /