‘Essential reading’ RUTGER BREGMAN

‘I love Hannah Ritchie’ JOHN GREEN

‘Essential reading’ RUTGER BREGMAN

‘I love Hannah Ritchie’ JOHN GREEN

‘Read

Also by Hannah Ritchie

Chatto & Windus

london

Chatto & Windus, an imprint of Vintage, is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies

Vintage, Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW

penguin.co.uk/vintage global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published by Chatto & Windus in 2025

Copyright © Hannah Ritchie 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset in 11/13.75pt Dante MT Std by Six Red Marbles UK, Thetford, Norfolk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

HB ISBN 9781784745745

TPB ISBN 9781784745813

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

Try to navigate climate change from the media, and you’ll get a daily dose of whiplash. Fossil fuels are going to destroy society as we know it, but the ‘green’ alternatives are just as bad: exploitative, expensive and a threat to the wildlife that we’re trying to protect. You’ll find headlines along the lines of ‘Clean Energy’s Dirty Little Secret’ in almost every news outlet, from the Guardian, Wired and The Economist to the Wall Street Journal and Fox News.

We’re apparently damned if we do switch to clean energy, and certainly damned if we don’t. It’s no wonder people are left feeling confused and doomed about how to move forward.

Faced with a seemingly unwinnable set of options, most of us seem to react in one of three ways. Some people do make the switch towards more climate-friendly alternatives but feel chronically guilty about it. They constantly question their decisions and never feel like they’re doing enough. This is no way to live (as I know from experience). Others become paralysed: they want to make a change but feel lost in the noise of conflicting information. They’re overwhelmed, indecisive, and end up sticking with the status quo (which is usually the least climate-friendly option). And finally, there are the backlashers: those who feel conned and lied to about the risks of climate change, or the solutions we’d need to fix it.

I meet and hear from these groups every week: in my inbox, on social media, from journalists, and audiences at talks and book events. They’re very engaged, but they are also very uncertain – and, frankly, often deeply defeated – about our chances of getting out of this mess. What’s most heartbreaking is that their vision of the future is so

at odds with the opportunity that’s in front of us. We could have a world run on clean energy, stopping climate change and giving us more breathable cities. We could build cities out of green cement and low-carbon steel, have comfortable homes (not too hot, or too cold) and no one living in energy poverty. We could feed 10 billion people on a fraction of the land we use today, and without killing tens of billions of animals every year. The future is there, waiting for us to take it. Or, rather, build it.

Climate change – and the energy, materials and food systems that drive it – is a massive but solvable problem. We already have many of the solutions we need. Others are still in the pipeline, but thanks to brilliant, tireless innovators, they are getting closer and closer to take-off. You wouldn’t guess it from public discussions, though. Newspapers, documentaries, podcasts and commentaries are filled with misconceptions and, in some cases, outright myths that plant deep seeds of doubt about our ability to make progress. They claim solar and wind plants aren’t that ‘clean’ when you consider all the fossil fuels that are needed to build them. That we won’t have enough minerals to build solar panels and batteries. That, rather than making our cities healthier, electric cars increase air pollution. The list goes on and on.

This book is my attempt to investigate and answer the most important and frequent questions raised by these contradictory and confusing claims. It’s a guide to help you navigate the minefield of information, and to help you sort fact from fiction when it comes to the solutions we urgently need. For those who are trying their best but feel they might be doing the ‘wrong’ thing, or not doing enough, I hope it brings focus to the biggest actions you can take. For the confused and paralysed, I hope it brings clarity and inspiration about where we go from here. And while I don’t expect to reach all the backlashers – those who have already turned cynical – there are always a few who are curious and open enough to listen. Ever the optimist, I’m happy to try.

The structure is very simple: 50 burning questions, and 50 straightforward answers. The answers are long enough to give a fuller picture and avoid the pitfalls of a clickbait headline, but only as long as they need to be to get the essential information across (some questions

have an extra ‘Things to bear in mind’ section at the end, which is for those who want to dig a bit deeper).

At the heart of every answer is data. That’s the only way to understand these solutions: their effectiveness, how big the trade-offs are, and how they compare to the alternatives. Admittedly, as a data scientist who has been studying these trends for years, I might be slightly biased about data’s power. But without it, people can hype up solutions that don’t work or exaggerate the downsides of those that do. In this book, I’ll try to cut through the noise with the best data, used in the right context.

There’s a lot of ground to cover: everything from public attitudes and polarisation to fossil fuels, renewables, nuclear power, transport, mining, food, and controversial topics like carbon removal and solar geoengineering. What emerges from the 50 answers is that there are no deal-breakers. That’s why it’s a ‘hopeful’ guide. We are not only capable of solving climate change but also poised to create a better future for ourselves in the process. To do that, we first need to understand that it’s possible, then get serious about building the future we want – a future that the media and public discourse would have you believe is impossible.

When it comes to climate change, speed is crucial. If we’re to have a chance of meeting our targets, we need to move quickly. Unfortunately, we’re getting stuck on questions already answered by scientists, engineers and economists many times over. We need to stop going round in circles and start building the solutions we need. This book is my attempt to cut through the noise, so we can quit chatting and get to work.

Before we dig into the details, here are three overarching things to keep in mind: 1.

Pushback doesn’t only come from fossil fuel companies

It’s tempting to pin all the blame for misinformation on fossil fuel companies and lobbying groups. Now, I don’t doubt for a second that fossil fuel companies have downplayed the urgency of tackling

climate change and have falsely criticised clean energy to make us sceptical that a move away from coal, oil and gas is possible. The health and profits of these companies rely on us doubting that we can move to sustainable energy. I believe they have been a huge obstacle to us making this transition to cleaner energy sources. But the reason we’re so confused is not all on them.

A staggering volume of misconceptions is published in both rightand left-wing media. Yes, much more of it comes from the political right, but even the most climate-conscious outlets like the Guardian have printed headlines that would make anyone sceptical that our solutions will make things better. In 2023, Rowan Atkinson, the ‘Mr Bean’ actor, caused an uproar among energy analysts when he wrote an article titled ‘I love electric vehicles – and was an early adopter. But increasingly I feel duped.’1 In it, he rhymed off countless points against the environmental credentials of electric cars, and encouraged people to stick with their combustion engines unless they had an ancient diesel car. Some of his points were just flat-out wrong. Other arguments were based on old talking points that had already been thoroughly debunked. Sure, you can argue that this was just one harmless article (and everyone’s entitled to air their opinion), but it was widely read and widely shared, even making it into discussions in the House of Lords. Many readers would have found his arguments convincing and assumed that they should wait until we have better alternatives to electric vehicles. That’s terrible advice: when it comes to climate change, we don’t have time to waste. And you can see why readers would feel information whiplash: in the morning they read about imminent ice-sheet collapse, and in the afternoon, they’re being told to slow down and wait before buying that electric car.

The Guardian did publish a response from an expert who does know the data.2 But as ‘Brandolini’s Law’ states: ‘The amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude larger than to produce it.’ More people read Atkinson’s piece than the rebuttal, and the damage was already done – an imbalance that is often true of misinformation. That’s the issue we’re facing: the cost of publishing poor information is incredibly cheap, which means it’s almost

impossible to keep up with the sheer volume that’s published every day. Experts – who usually have full-time jobs so can only try to clean up the mess in their spare time – don’t stand a chance.

I don’t mean to pick on Mr Bean or the Guardian. There are countless other examples that I could have chosen. It’s precisely because the Guardian takes climate change so seriously that this example makes my point clearly: politicians, investors and the public are being fed conflicting information from all angles. It’s everywhere.

You can even find examples of pushback from groups who have dedicated their lives to environmental protection. Nuclear power has faced constant opposition, which in some countries has led to the continued burning of fossil fuels (with terrible impacts for climate change and deaths from air pollution). Even some solar and wind power projects have faced protests from environmental NGO s and Green political parties.3, 4

This comes from a growing tension between traditional environmentalism and what needs to be done to solve climate change. Until recently, environmentalism has been about ‘stopping stuff’: new coal plants, oil pipelines, gas drilling, highways, mines and infrastructure that encroach on nature. But to tackle climate change, we need to do the opposite: we need to build stuff. A lot of it, and we need to do it quickly. This is the dilemma that environmentalists (myself included) are wrestling with: conservationism has been about blocking and delaying; climate action is about building and accelerating. That’s why we sometimes see headlines about green groups opposing clean energy projects. They want to protect some of the landscapes that might be impacted by power pylons and solar farms, but this can come at the cost of more climate change. As will be seen later in the book, I think we can responsibly build clean energy, using less land than most people expect.

To be clear, I’m not saying that this is the reason we’re in this mess. Environmental activists have played a crucial role in bringing many of the positive changes and progress that we’ve seen over the last few decades. We’ve got a lot to thank them for. But when the public sees the strongest and most vocal environmental groups blocking renewable energy projects and other climate solutions, it’s not

surprising that people start having doubts: ‘If the greens are opposing it, then maybe solar farms do need too much land.’

So many people still get the basics wrong: more than half of Americans think electric cars are worse for the climate than gasoline, most Brits don’t know that nuclear energy is low-carbon, and almost everywhere, people underestimate how many others in their country support more climate action (especially among conservatives).5–7 Faced with so much conflicting information, it’s easy to see why.

Another reason why I think many people struggle to get clear answers is because the answers aren’t always clear. At least, they’re not intuitive. Confusion about climate solutions is not a case of people being dumb or gullible. It’s not obvious that heat pumps running on gas need less gas than a boiler; or a world of vegans would need less cropland, not more. It’s not even obvious that a low-carbon world might need less mining. Some of the questions in this book I didn’t know the answer to until I crunched the numbers. Many of the doubts that people have stem from some nugget of truth. They’re half-truths. That’s why they’re so convincing. It does take more energy to manufacture an electric car than a petrol one. Wind turbines do kill birds. And poorer countries will need to use some more fossil fuels over the next few decades. What’s missing is the context we need to understand whether these are problems we can overcome or deal-breakers that mean our path forward is doomed.

2.

Another problem is that we seem to be stuck in something I call ‘perfect solutionism’. People seem to expect solutions to climate change that have no downsides, or they’ve been falsely promised them and then feel short- changed when that false promise is exposed. Unfortunately, perfect climate solutions don’t exist. We have good – even great – ones, but many have some environmental or social cost that we need to wrestle with. When I say ‘clean energy’ throughout this book, I really mean ‘cleaner energy’ because no energy source is completely pollution- or impact- free.

We need to be honest about these effects and trade- offs. We also need to recognise where a search for perfection will leave us: in a much hotter world, still hooked on fossil fuels, with millions still dying from air pollution. If we want to move forward, we need to let go of this search for silver bullets.

This perspective matters for how we assess the merits of different solutions. Comparing the waste, mining or biodiversity impacts of renewable energy to a world without energy is pointless. Yet that’s the comparison that many commentators and critics seem to make. What’s more useful is to see how solar or wind power compares to the electricity system we have today: one that mostly runs on coal and gas. No, the impacts of solar and wind are not zero. But they are much, much better than fossil fuels.

The notion that one day all our problems will be solved is attractive, but it’s an illusion. This is not just true of climate but of social, economic and environmental problems more broadly. Each generation solves problems and creates new ones for those who come after them. Antibiotics have saved hundreds of millions of lives (at least), but there are now concerns about antibiotic resistance. Would I want to go back in time and undo the miraculous discovery of penicillin and other antibiotics? Of course not. Yes, we have a new problem to contend with, but it’s much smaller than the previous one. This is how progress happens – incrementally, from one generation to the next. But it’s a journey with no finish line; humanity will never be problem-free. As the physicist David Deutsch explains in his Three Laws of the Human Condition:

1. Problems are inevitable.

2. Problems are solvable.

3. Solutions create new problems, which must be solved in their turn.

So, yes, in solving climate change, we will hand down some new problems that our children or grandchildren will have to deal with. They might need to figure out a new form of mineral recycling. Or they’ll have to manage small amounts of nuclear waste that we’ve

buried. Do you think they’d rather we handed them the challenge of figuring out how to recycle copper cables, or unchecked climate change leading to a 4°C warmer world with struggling crops and unbearable heatwaves? The point is not to deny Deutsch’s point 3 – that climate solutions will inevitably create new problems – but to see them for what they are: smaller, solvable problems rather than massive barriers that block us from moving forward. Instead of throwing our hands up in the air in despair, we need to roll our sleeves up and figure out how to tackle them.

There are things we can do to reduce the impacts of renewable energy, electric cars, meat substitutes, and the other things needed to tackle climate change. But we’ll have to learn to walk and chew gum at the same time. We need to deploy these technologies, invest money and form policies while we work on making them better. We simply don’t have time to do one after the other.

What you do matters: the false dichotomy of systemic and individual change

We will never achieve perfection, but we can always strive to make things better. That’s why I’ve included a section in every question called ‘What we need to do’. This provides a list of the actions we can take to overcome barriers that are currently getting in the way, and things we can do to make this transition as socially and environmentally responsible as we can. These lists include a mix of actions that individuals can take and those that need to be taken by governments, companies, media or broader society.

When I speak to people who are deeply concerned about climate change and want to make a difference, the feeling that comes through most is helplessness. There’s a sense that what they do is pointless. But to say that you or I can do nothing to change things around us is a lie. No, neither of us is going to transform the world or fix climate change on our own – let’s not be delusional – but how we think and talk about these problems matters.

Solving climate change is often framed as either a systemic problem

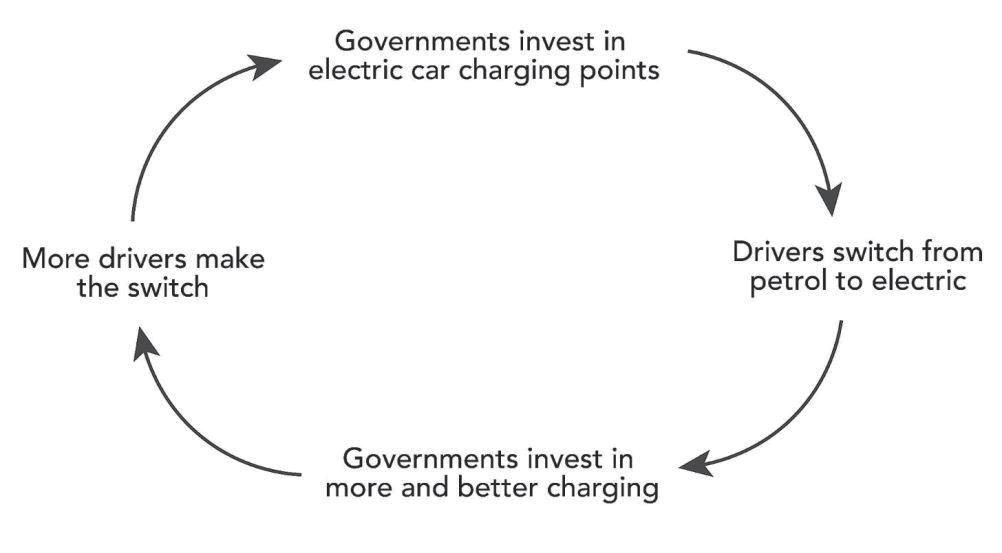

that governments, big business and the financial system need to solve, or one that will be solved through individual behaviour change (if everyone ‘just did their bit’ we could fix this). But both matter, because they feed into one another. You are part of the system, not separate from it.

Let’s take a simple example of shifting the world from petrol cars to electric ones or public transport. You could argue that this is a systemic problem: it’s on governments to make sure that there are enough public charging points, bus routes and train lines; it’s on manufacturers to build great electric vehicles; and some combination of the two to make both options cheaper than driving a petrol car. Those points are all true. But governments and companies are never going to step up unless they know that the public is also on board. There’s no point in setting up an electric charging network if individuals refuse to give up their petrol cars. No point investing in public transport if no one wants to take the bus. In 2024, the Scottish government ran a trial where it cut the prices of rail journeys during peak hours to incentivise more commuters to take the train. The problem? Not enough people made the switch, and it wasn’t financially viable. Positive systemic change can’t happen in a vacuum; it needs a positive response from individuals, too.

Systemic change is reinforced by individual changes: it’s not one or the other

This means that what you do on a personal level – whether it’s eating less meat, taking public transport, getting rid of your petrol car, or ditching the gas boiler – matters. But so does your support for the large system-level changes that we’ll need. Systemic change is driven by culture and public sentiment, and how we all think and talk about climate solutions shapes that culture. So no, you and I won’t be able to fix human rights abuses in mineral supply chains or ensure that nuclear waste is stored and buried safely, but knowing what can and needs to be done at a societal level is crucially important for us as individuals. So yes, in the ‘What we need to do’ sections of each question, focus on the changes that you can make in your own life, but don’t dismiss the systemic changes we need as things that ‘someone else needs to think about’. You and I need to understand them, so we can push for the right things too.

We’re going to start by tackling a bunch of questions that suggest even trying to fix climate change is a total non-starter. If we can’t overcome them, then discussions about specific climate solutions – whether we have enough minerals, or whether wind turbines are bad for birds – are irrelevant. These doubts are framed around the idea that it’s too late to do anything, that change is impossible, or that the efforts of individual countries are pointless. They’re often successful in making us feel like the future is bleak and we’re powerless to do anything. I’ve felt that way before. But thankfully these doubts can be overcome.

Isn’t it too late? Aren’t we heading for a 5 or 6°C warmer world?

Answer: Every tenth of a degree matters. There’s no point at which it’s too late to limit warming and reduce damage from climate change.

I read Mark Lynas’s book Six Degrees: Our Future on a Hotter Planet when I was 14 years old, and it scared the life out of me. Lynas takes the reader on a journey of what to expect from a world that’s 1 degree warmer, 2 degrees, 3 degrees, all the way up to 6 degrees. By the middle of the book, your blood pressure is high; by the end you’re on the floor.

It is a well-researched book that offers us a window into many possible futures. Fortunately, the scientific consensus has moved away from the most extreme scenarios since its publication. Unfortunately, a lot of the public messaging has not. Many people believe a pathway to 5°C or 6°C is already locked in, and the only thing we can do now is prepare for the worst.

Let’s look at what the latest science says about where we might end up by 2100.1–6

➤ Current policies. This is where we would end up based on the climate and energy policies that governments have already put in place. If no countries stepped up their efforts and we continued with current enacted policies, we’d end up at 2.5°C to 3°C higher than pre-industrial temperatures by the end of the century.

➤ 2030 commitments If countries met the targets they set for 2030, but enacted no policies afterwards, we’d end up at 2.4°C.

➤ Net-zero pledges. Many countries have set ambitious targets to reach ‘net-zero’ emissions – most by the middle of this century. If they achieved this, we’d be in a 1.8°C warmer world.

This is both good news and bad news.

The good news is that we’re no longer heading for the worst-case scenarios that scared me as a teenager. The plunging costs of solar, wind, batteries and electric vehicles, a step up in national policies, and a better understanding of what our energy future might look like have taken us off that terrifying path. And, importantly, countries have put commitments on the table that would keep us ‘well below 2°C’. Now, we’d be naive to assume that they’ll all deliver. But it does give us concrete pledges that we can hold governments to account on.

The bad news is that one of our global targets of keeping temperatures below 1.5°C of warming is now out of reach. And a 2.5°C warmer world – which we’re on course for – is still a scary and unacceptable one. It could spell the end of many coral reefs. It could cause significant damage to food production, especially in some of the poorest countries. Large parts of the world will experience gruelling heatwaves. Arctic sea ice will be gone in the summer. Ice sheets are at a much higher risk of becoming unstable. We really want to avoid ending up there. And we can: 2.5°C or 3°C is not ‘locked in’. There is still time to put ourselves on a better trajectory.

First, we can talk and think about our climate trajectory and targets in a more helpful way:

➤ Be honest about where we’re heading. The 1.5°C target is dead. If our carbon emissions dropped to zero tomorrow, we could achieve it. But the reality is that our emissions aren’t going to fall quickly enough (I’m optimistic but

I’m not delusional). We need to be honest about this for a couple of reasons. One, countries need to adapt to the post-1.5°C world we’ll soon be living in; pretending this is not going to happen robs them of the time they need to prepare. Two, the public – who are repeatedly told that 1.5°C is still within reach – will start to lose trust when we pass that target.

➤ Don’t throw in the towel. That’s the most important message here: there is no point of no return that makes it pointless to act. Our 1.5°C and 2°C targets are not cliffs or thresholds. Every tenth of a degree is worth fighting for as it reduces the impacts of climate change and limits the damage that’s to come. 1.7°C is better than 1.9°C, which is better than 2.1°C. Stop obsessing over arbitrary targets and focus on how you can help to reduce our carbon emissions as quickly as possible (see below).

➤ Watch out for headlines based on worst- case scenarios . We’re not on the same trajectory to 4°C or 5°C that we thought we were a decade ago. Unfortunately, a lot of reporting and studies are still based on these worst- case scenarios. It’s sometimes hard for non- experts to know what scenario is being assumed without reading jargon- filled academic papers. My one quick piece of advice is to look out for any mention of ‘ RCP 8.5’: this is the acronym of the worst- case (but now implausible) scenario that has often been used in climate modelling. 7 , 8 Of course, knowing the impacts of these extreme cases is useful for scientists, but not for policymakers or the public, who assume that this is the most likely outcome. It does make for a great apocalyptic headline, though.

Second, here are the most effective things you can do to reduce your personal carbon footprint (many of these – and the questions you might have about them – are covered later in the book):

➤ If you drive, then cycle, walk or take public transport more. If you need a car, then an electric one is much better than petrol or diesel.

➤ If you fly, this will be a big chunk of your footprint. I won’t tell anyone to stop flying completely (because for most people, it’s not going to happen) but reducing the amount you fly would make a massive difference.

➤ At home, heating and air conditioning will be your biggest energy-guzzler. Getting your home insulated, and switching a gas boiler for an electric heat pump will slash your home’s footprint (and your bills).

➤ Installing solar panels at home will also reduce your carbon footprint while cutting your energy bills. Some can’t afford the upfront costs – or rent a flat where they don’t have the option of putting up solar panels – but it’s a worthwhile investment for those who can.

➤ Switch to a renewable energy provider. This also sends a signal that more and more people care about climate change and want low-carbon energy.

➤ Eat less meat and dairy and move to a more plant-based diet. This doesn’t mean you have to go fully vegan; for many, the all-or-nothing approach is daunting. But you can still have an impact by cutting back, especially on beef and lamb.

➤ Stress less about the small stuff – recycling, plastic bags and food wrappers, food miles, turning the lights off, leaving devices on standby – especially if it comes at the expense of the big things that are listed above. This is a concept called ‘moral licensing’ where people feel like they’ve contributed with the small stuff, and therefore ignore their carbon- intensive behaviours. People will often feel proud about bringing their plastic bag to a supermarket (which has a tiny carbon footprint) and then fill it with meat and dairy (which has a much bigger impact).

These individual actions on their own are not going to get us there, of course. At a societal level, we need to go bigger and faster and:

➤ Deploy low-carbon electricity sources like solar, wind, nuclear and geothermal as quickly as possible. To do that, we’ll need massive reforms around infrastructure projects so they can be completed quicker.

➤ Accelerate advancements in batteries: these technologies hold the key to the energy transition.

➤ Electrify as many sectors as we can: road transport, heating, steel manufacturing, short-haul aviation. This is the most efficient way to decarbonise.

➤ Reduce global meat and dairy consumption; innovate on high-quality protein alternatives.

➤ Invest in forest and ecosystem restoration to suck up lots of carbon.

➤ Continue innovating in sectors that are not yet ready for large-scale deployment: cement and steel manufacturing, long-haul aviation, and ways to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

One of the most common questions I get asked is: won’t we reach a point where it’s game over and our planet’s systems collapse, a point where we trigger runaway warming?

Tipping points – a threshold where a system moves into an irreversible state – matter, but they don’t change what we need to do now to reduce emissions. There are a few key misconceptions about tipping points that are worth looking at here.9

First, people often think that the planet has one single tipping point. Or they assume that the 1.5°C or 2°C targets themselves are a global tipping point: that once we pass them, we’re thrown into

oblivion. That’s not true. There’s nothing special about 1.5°C. Things are not fine at 1.49°C but disastrous at 1.51°C.

Rather than there being a single global tipping point, there are a range of local or regional systems with different ones. Tropical coral reefs are one. The Amazon rainforest is another. The Greenland ice sheet. The Antarctic ice sheet. They won’t all ‘tip’ irreversibly at once. While scientists don’t know exactly what temperature would trigger these individual points, there is a real risk of doing so, especially as warming gets towards 2°C. We shouldn’t hide from the devastating impacts this would have on regional ecosystems. But it’s not the case that they will set off runaway global warming, taking us to 5°C. Some tipping points will increase global temperatures a bit, but not by whole degrees. For example, if we were to have sea-ice-free summers in the Arctic (which seems likely)10 this would increase global temperatures by around 0.15°C.11 A tipping point in the Amazon might have a similar effect. Hitting several of them could increase temperatures by 0.3°C or 0.4°C. That’s a lot. But it’s not the same as an abrupt change to a ‘Hothouse Earth’.

Another misconception is that these tipping points happen quickly: that if the Greenland ice sheet collapsed, sea levels would rise by 10 metres within years. Most of these large tipping points – like ice sheets – play out over centuries or even millennia. It might be 2500 or later before the ice sheet is mostly gone. Now, that would still be terrible – we don’t want to hand that problem to future gener ations. But it’s a very different problem from our coastlines shrinking within a decade, which is what people assume when they think about ice sheets ‘collapsing’.

We can still stop this by reducing our emissions and keeping temperatures as low as we can. And almost all scientists agree that it’s never ‘too late’ to prevent more damage.

Is there enough public support to tackle climate change?

Answer: Not everyone cares about climate change, but the majority in every country does.

More people care about climate change than you think. A survey of 59,000 people across 63 countries found that 86% thought that humans were causing climate change and that it was a serious threat to humanity.12 Nearly three-quarters supported climate policies including carbon taxes on fossil fuels, expanding public transport, more renewable energy, more electric car chargers, taxes on airlines, and protecting forests.

In the chart, you can see the results of another survey across 130,000 people in 125 countries. Eighty-nine per cent wanted to see more political action and 86% thought people in their country ‘should try to fight global warming’.

This is even true in ‘climate-sceptical’ America. In that same survey, 74% of Americans thought that the US should be involved in international action to tackle climate change. To make sure that this wasn’t just a single fluke study, I looked at more surveys; the results were similar. Sixty-seven per cent of Americans thought that developing alternative energy sources was more important than expanding fossil fuels.13 Seventy-one per cent said that climate change is already causing harm to people in the US today.

Support is higher in Europe. A survey in the European Union found that 93% of people believe that climate change is a serious problem.14 More than two-thirds think that their government is not doing enough.