‘Utterly compelling’

Also by David Rooney

‘Utterly compelling’

Also by David Rooney

David Rooney

Chatto & Windus

Chatto & Windus, an imprint of Vintage, is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies

Vintage, Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW

penguin.co.uk/vintage global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published in Great Britain by Chatto & Windus in 2025

First published in the United States of America by Norton & Company in 2025

Copyright © David Rooney 2025

David Rooney has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

HB ISBN 9781784745080

TPB ISBN 9781784745097

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

Th is book is dedicated to

FREDERICK “FRED” RAYNHAM

and all the other aviation pioneers— men and women, of all ages, from all walks of life— who risked everything: for freedom, for progress, and for us.

HARRY HAWKER AND MAC GRIEVE HAD BEEN FLYING EAST OVER the Atlantic Ocean for ten hours when the end came.

The fl ight had started in rocky, snow-covered Newfoundland well enough. The men had planned the long fl ight carefully. After a slightly shaky take- off, when they nearly crashed into a ditch, they made good progress.

But soon, things started to go wrong.

They hit fiercer storms than the meteorologists had predicted. Nobody really knew what the weather was like a mile or two above the mid-Atlantic because nobody had been there before. As Hawker called on the aeroplane’s engine for more power so he could skirt around the worst of the storm, he found that it had developed a fault. It wasn’t a fuel shortage, nor a mechanical malfunction; there was a problem with the cooling system. The water in the radiator wasn’t getting around the engine, so it was overheating. The men tried to cure the problem in a series of risky manoeuvres. But it was no good: the coolant was boiling off fast, and when it ran out, the engine would soon seize.

They came down low over the roiling Atlantic waters to look for somewhere to ditch, and for a ship that might pick them up. Two hours of searching, as the radiator’s pressure-relief pipe spewed steam in front of them, proved fruitless.

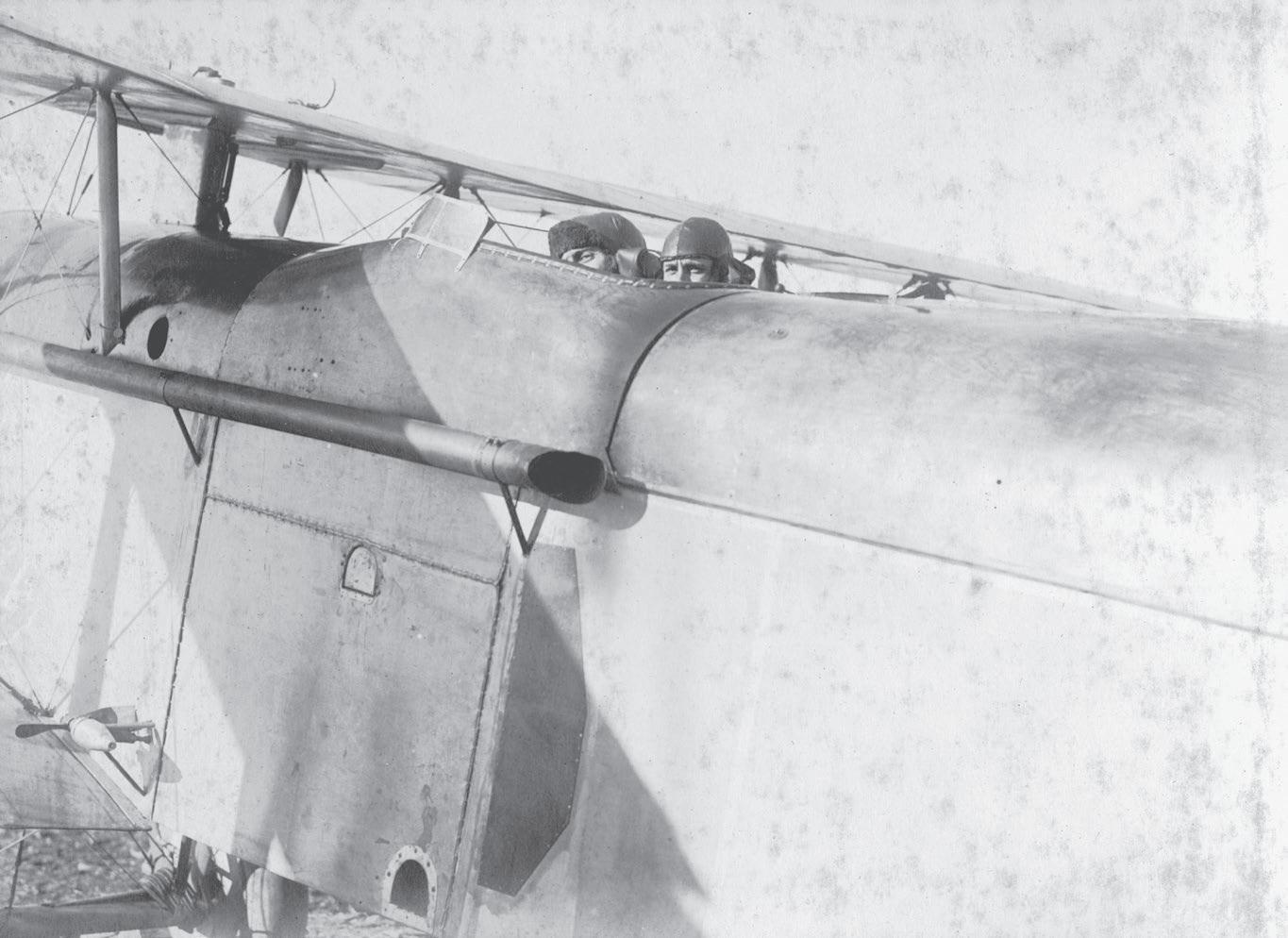

Hawker and Mac Grieve in Newfoundland, ready to attempt the Big Hop.

The thirty-year-old Hawker had years of experience and was considered one of the best pilots in the world, but he was highly strung. When things were going wrong, he could be moody and impatient. He struggled with the controls as the storm tossed the aeroplane around the sky. It was like cresting a rollercoaster repeatedly, and the pit of his stomach heaved each time. Before long, he was vomiting over the open side of the cockpit. Grieve, the navigator, was a navy man, nine years older than his partner and more stolid. He had been trying to work out their position with his sextant, drift indicator, and compass. But the rain squalls and dense clouds had cut him off from the sun and stars, even if he could have held the sextant still enough as the aircraft lurched. In the end, he joined Hawker in scouring the sea for salvation.

They flew back and forth in a zigzag, but the scene—what little of it they could glimpse as they stared into the storm—never changed. The sky was theirs and theirs alone. The ocean, a turbulent grey waste 400 feet beneath their cockpit, was hiding the steamships that ploughed its

frigid waters. The wireless set that might have alerted a ship to their distress hadn’t worked all through the fl ight. The men had flares on board: bright red lights that could be fi red high into the sky from a pistol. But they would be useless in fog like this. The cloud was too thick, and the flares would sputter out in moments anyway.

The two aviators had flown a thousand miles from Newfoundland in their two-seater aircraft with its open-topped cockpit. They’d have to fly another thousand to reach where they planned to go: Ireland.

The wind and spray whipped their faces raw. The harsh growl of the engine assaulted their ears and the heady fumes of gasoline exhaust flowed around their cramped enclosure. They knew that millions of people around the world were willing them along on their flight. But the men had never felt more alone. They were now resigned to the fact that they would not make it across the ocean. There they were, at eight o’clock that morning: a speck of humanity waiting to die in an angry Atlantic storm. Finally, the last drops of precious coolant in their engine boiled away.

IT WAS MAY 1919. HAWKER AND GRIEVE WERE AMONG SEVEN AVIAtors that summer who would take off from Newfoundland, intending to land on the shores of the British Isles without stopping along the way. The contest for the fi rst nonstop transatlantic fl ight was sponsored by Britain’s Daily Mail newspaper. It was known to some, especially in the United States, as “the Big Hop.” Only two of the seven airmen would make it across successfully. The others would fail in their endeavours.

Yet they all achieved something which, at the time, was akin to greatness. Even before they went out to Newfoundland in the spring of 1919, each of the seven airmen possessed a life story that could fi ll a book or a movie screen. They ranged in age from twenty-five to thirty-nine. Th ree of them were to act as pilots, and four would be navigators; all seven had trained to fly at one time or another. Each had experienced more in his short life than most people could comprehend.

As the events of 1919 unfolded, the contestants were feted on both sides of the Atlantic by a public hungry for stories of success. The terms

Mac Grieve, Fred Raynham, Harry Hawker, and Charles Morgan, four of the contestants getting ready in Newfoundland to fly the Atlantic in 1919.

of peace after the Great War had not yet been agreed. The influenza pandemic, its waves still washing around the globe, would take many more lives than the war. The transatlantic fl ight contest offered a welcome distraction. But the public adulation that summer faded fast. The story of the Big Hop was quickly forgotten once the contest was over. Those who took part were modest and did not seek glory. The public, for their part, realized they were weary of seeing the dangerous consequences of aviation. Families had lost enough young aviators in the war to know that fl ight could be a world of pain as well as promise. Perhaps the contest didn’t feel so glorious in the end.

Some of that pain faded a little as the 1920s wore on. Civilian air travel gradually established itself, at least over short distances. Aircraft and their engines improved, and flying became more of a fi xture in the world as its worst dangers receded from view. It was this later world, not the one just emerging from the war, that was truly ready to celebrate transatlantic flying. It was an eighth airman, the American Charles

Lindbergh, who fi rst flew the Big Hop alone. He made his solo transatlantic fl ight in 1927, and the eight years that had passed since 1919 made a lot of difference. His achievement made him a lasting celebrity. Bestselling books and a blockbuster movie kept his accomplishment in front of the public’s eyes for decades. In 1932, Amelia Earhart made the second nonstop solo crossing, and she caused a sensation as well. These later successes only pushed the story of 1919 still farther into the shadows. Many today still think Lindbergh was the fi rst to fly the Atlantic.

The seven airmen of 1919 each learned to fly on fl imsy aeroplanes made of timber struts and varnished fabric; aeroplanes which could carry two people at the most. By the time the last of the seven men died, in November 1970, Boeing 747 airliners had been in service across the Atlantic for almost a year. Each of these jumbo jets at take-off weighed 300 tons. They carried upwards of 400 passengers at 600 miles per hour in luxurious comfort. It wasn’t long before such fl ights became commonplace, then mundane.

Today, a transatlantic fl ight is an unremarkable part of everyday life. It is almost a chore. But somebody had to go fi rst.

They are heroes, modern ones, who can compare with those of Greek, Norse, and Roman fame, and their deeds are making history. Their lives are so various before they have taken up their calling that one cannot account for their choice. It mostly comes suddenly, and with such force that every obstacle is overcome to reach the desired end.

— HILDA HEWLETT, AVIATOR, 1917

ON A QUIET SATURDAY EVENING IN MARCH 1911, IN THE SMALL Australian ranchers’ town of Caramut, an intense twenty-two-year-old garage mechanic found himself in a hotel dining room, telling his friends why he was leaving for England.

Harry Hawker was born in January 1889 in Moorabbin, a township set among orchards and market gardens a few miles outside Melbourne. His father, George, was of Cornish extraction. In another life George Hawker might have become a miner. But the Victorian gold rush had slowed to a crawl before he was old enough to swing a pickaxe and dig for his fortune. Instead, he set up as a blacksmith and wheelwright, building wagons for the Chinese market gardeners transporting their fruit and vegetables along the Nepean Highway to Melbourne every day. He built his own steam engine for the workshop, and his own car, using a lathe driven by foot pedals and a pillar drill powered by hand. When Harry came along, the third of four children, he soon absorbed his father’s obsession with mechanism. He once told a magazine reporter that he was “crawling under machinery from the age of three.”

Harry’s childhood was a regimen of strict discipline and perpetual activity. His father was a prize-winning rifle shot and served as a sergeant in the local militia. He was also a Methodist missionary who preached that idleness was a sin. “Don’t stand around doing nothing,” he would

admonish his children; “do something, even if it is wrong.” Every Sunday morning and evening, Harry and the family would worship at the local Methodist church. The rest of the time they would be working. They kept cows for milk, chickens for eggs and meat, and horses to ride. They grew their own vegetables, made their own butter, and baked their own bread. Such an active home life left Harry with little appetite for academic study. School was a place he tolerated each day until he could escape its confines and return to his tools. He left school in 1901, aged twelve.

Hawker spent his early teens hopping around Melbourne from one motoring job to the next. Fired with the mechanical zeal of his father, he chased any opportunity to work with the latest cars, the fastest motorcycles, and the most powerful engines. He was soon able to extract the fi nest performance from any petrol motor and developed a reputation as one of the best mechanics around. “He thinks in gears, wheels, bores and strokes,” his brother-in-law once observed. People also started to realize he was something of a maniac for speed.

At seventeen, Hawker took up work in the rural township of Caramut, 150 miles from Melbourne. It was a remote pastoral settlement for sheep and cattle ranchers with a population of just two hundred. After a couple of years, he picked up a position working for Ernest de Little, a polo player and former fi rst-class cricketer who had taken up pastoral farming there. He developed a nice little life. There was the spacious workshop, with its modern lathe, its tidy workbenches, and whatever tools Hawker wanted. There was the Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost that he drove for de Little, who collected fi ne motor cars but didn’t want to drive or fi x them himself. There was the generous salary, paid by de Little for a job that was hardly full time for somebody with Hawker’s talents. His lodgings at a comfortable Caramut hotel, run by kind and indulgent owners, were covered. And he could run his own engineering business on the side. But he was growing restless. He wanted more than rural Victoria could offer somebody like him: he wanted to escape.

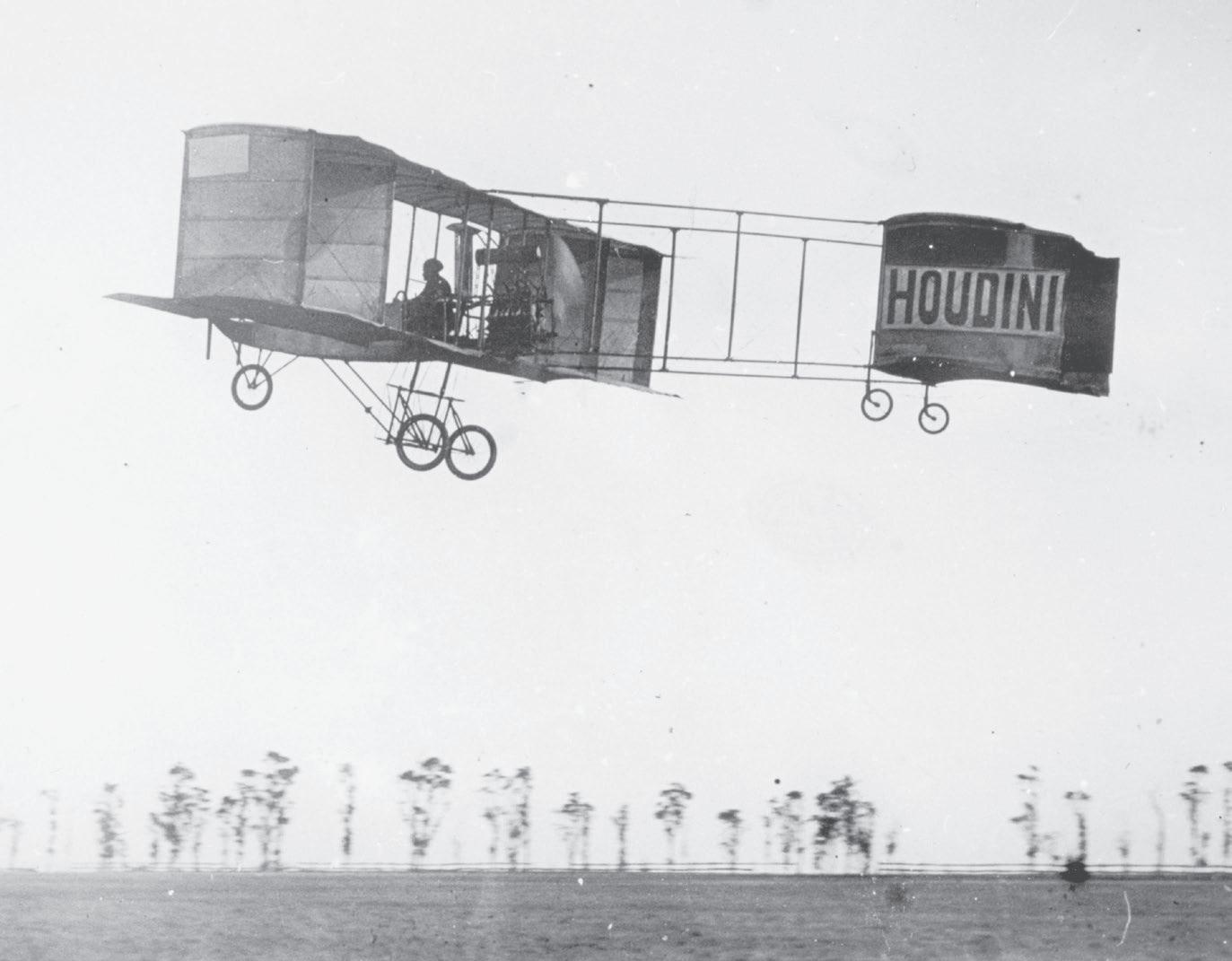

In March 1910, he experienced an epiphany when he witnessed Australia’s first aeroplane fl ights. They were made by the famous escapologist Harry Houdini over dry grassland at Diggers Rest, twenty miles outside

Melbourne. It’s likely that the twenty-one-year-old Hawker helped overhaul Houdini’s engine when it developed a fault. The young Australian certainly discerned in the episode a way out of his small-town existence. After one fl ight, Houdini told a reporter, “As soon as I was up all my muscles relaxed, and I sat back, feeling a sense of ease. Freedom and exhilaration, that’s what it is.” Hawker wanted in. He wasn’t prepared to settle for a life constrained by status and geography. He wasn’t content with the cards he had been dealt. He must have taken the view that if you stood still in the fast-changing modern world, you would take root, stagnate, and die inside.

Harry Hawker was a short young man, considered good-looking by his friends, who dressed in smart double-breasted jackets, high-waisted trousers tapering to the ankles, and shoes with high heels to elongate his diminutive frame. He had a tight, angular body, a mop of curly black

Harry Hawker in 1912, aged twenty-three.

hair, and eyes that seemed to burn with restless energy. One writer said, “In his black Celtic eyes glow fi res of Celtic enthusiasm,” and that “his jaw has the fi rm line which spells ‘grit.’ ” He favoured actions over words, with admirers describing him as “manly and sporting.” Like his father, he took up the rifle and became a crack shot. He was a keen and fast boxer who could, as one friend recalled, “hit like the kick from a mule.”

In conversation he had a tendency to joke around or become argumentative. Long discussions bored him. His friends soon learned to spot the telltale sign of impatience: a quick shake of the head to toss the thick curls off his forehead. It was as if, said an acquaintance, “he wanted more air.” When he did have something to say, Hawker spoke economically, and people tended to listen.

In the dining room of the Western Hotel in Caramut in 1911, he seemed to hold the gathered well-wishers in a spell as he told them why, after five years in the township, he had decided to leave. He was heading for England “to become further acquainted with motor science,” he

reportedly said, “and to study aviation.” He was never short of Aussie optimism. He confidently assumed he would just walk into a job.

But when he reached the old country, the bruising reality of the situation hit him hard. Work was difficult to come by. He was an outsider, brash and confrontational, with no references and little inclination to flatter and plead. It was a humiliation. In letters home, Hawker fumed about the “Pommy bosses” who rejected his applications. But he persevered. His fi rst job, after two months of searching, was with the Commer commercial vehicle company in Luton, twenty-five miles north of London. Its pay was low, so, after six months, he took up a slightly better-paid position at the London agent for Mercedes cars. He only stayed there two months before quitting for the nearby Austro-Daimler company, which offered another small increase in pay. He was relieved to be in work, but weekly visits on his days off to watch the flying at the nearby Brooklands aerodrome and racetrack only cemented his ambition to join the aviators competing for the freedom of the open skies.

In June 1912 Hawker heard that a young man called Tom Sopwith was looking for a mechanic to work at his Brooklands flying school. Sopwith was just a year older than Hawker. Like the Australian, he had grown up with a fascination for mechanism and an aversion to academic study. When he reached his teens, Sopwith planned to join the Royal Navy, but they turned him down. “They didn’t think I was clever enough, and they were probably right,” he later commented. Instead, he attended an engineering college on England’s south coast, where he immersed himself in the practical study of motor vehicles. In 1905, at the age of seventeen, he left. A sizeable inheritance had left him comfortably welloff. With a childhood friend, he started selling motor cars in London, and business went well. He took up yachting and competed in speedboat contests on the side. He also raced motor cars at Brooklands and elsewhere, winning trophies and surprising some trackside spectators who thought the serious-looking driver with the baby face could barely have reached his teens.

At eighteen, Sopwith took up ballooning. He loved the challenge of it, but found it a capricious pastime. He nearly lost his life on one fl ight

when high winds pushed the craft along so quickly that he was almost past England’s west coast and over the Atlantic before he could bring it down to land. Then, just like Hawker, he had an epiphany. In 1910, aged twenty-two, he spent £5 on a short aeroplane joyride at Brooklands. He found the sense of space and freedom in the open skies euphoric. With the funds at his disposal, and with his relentless have-a-go attitude, he bought his own aeroplane, taught himself to fly it, and passed his tests. Then he spent two years travelling the world to compete in flying contests. He won more than he lost and made good money from the prizes on offer. Before long, he realized there could be a business in aviation. In February 1912 he set up his Brooklands flying school, and later that year, he branched out into aeroplane manufacture at the nearby town of Kingston.

When Harry Hawker turned up to enquire about the position for a school mechanic, he was in luck. Years later, the story went that Sopwith told Hawker he only wanted shop boys. Hawker reportedly replied, “All right, I will sweep the shops!” Whatever was said that day, Hawker got the job. He quickly demonstrated his prodigious technical skills. He also started to show his old swagger. A friend recalled that he had “soon made it clear that he was to be more than just another cog in the wheel,” though his assertive attitude could sometimes create friction with his new workmates. Before long, he asked for flying lessons, and Sopwith agreed. Within a month, Hawker passed his tests.

Now that he was a qualified pilot, he wanted to test the extent of his talent. Tom Sopwith’s experience proved that reputations and money could be made in fl ying contests. Hawker decided to follow suit. An endurance competition funded by the Michelin tyre company, which offered an impressive trophy and £500 to the pilot who could fly longest without touching the ground, looked like the perfect opportunity to prove his mettle. It might also be a fi nancial lifesaver. For aviators from modest backgrounds, the money put up in contests was what allowed them to keep fl ying. The Michelin competition closed at the end of October. Hawker decided to take the prize for the Sopwith company.

1910.

THICK FOG COVERED THE BROOKLANDS FLYING VILLAGE ON THE morning of Thursday, October 24, 1912. At least it dampened the stench from the sewage farm, but that was about all it had going for it. Following the rainstorms and high wind earlier in the week, it was looking like another bad day to fly. In weather like this, it was more likely somebody would get themselves killed than break a record.

Along the railway embankment that marked the north-west boundary of Brooklands, steam trains chugged through the gloom. They were carrying affluent Surrey residents, and goods from Southampton and Portsmouth, into London, twenty miles up the line. People with lodgings in nearby Weybridge and Byfleet made their way to the aerodrome by foot or bicycle. Others came longer distances, travelling in the dark early hours on motorbikes. Some could afford neither lodgings nor ground transport. They might sleep in the wooden sheds that constituted aircraft hangars, if they could get away with it. As the flying village started com-

ing to life that morning, the sound of hand tools clattering and scraping began to rise as people got to work. In the engine workshop, the shrill keening of lathes and milling machines started to pierce the autumn air. The smells of lubricating oil and gasoline and sawn timber and fabric lacquer hung heavy and intoxicating over the sheds.

Six years earlier, Brooklands had been a 330-acre tract of woodland, marshy meadows, and poultry farms. The River Wey wandered sluggishly across the site, passing under the railway embankment on its way to join the Thames. Low hills clad in pine trees rose in the east, overrun with rabbits, which the residents of Weybridge would attempt to snare.

The vast site was part of the 4,600-acre estate inheritance of Hugh Locke King, who lived in one of the elegant country houses close to the railway station with his wife, Ethel. The inheritance had given them the means to pursue extravagant pastimes. The Locke Kings became keen Edwardian motorists. But they grew frustrated by the speed limits that stopped motor racing from taking place on Britain’s public roads. In 1906, Alfred Harmsworth, the determined forty-year-old proprietor of the Daily Mail newspaper and himself a motoring devotee, encouraged the Locke Kings to build their own private track where cars could race without limits, and they liked the idea. They decided to turn the marsh and woodland near their home into a purpose-built two-and-threequarter-mile racing circuit.

For eight months, two thousand workers living in corrugated-ironand-timber huts shifted 400,000 tons of earth, chopped down thirty acres of woodland, grubbed up carpets of bluebells, diverted the river, and demolished the two farms that tried to scratch a living on the unpromising land. Then they built vertiginous banking at each end of the site, higher than the houses behind it. They connected the two banked ends on one side by a half-mile-long straight that ran alongside the railway embankment. On the other side was a gentle reverse curve. They bridged the river in two places. Finally, 200,000 tons of concrete, to a thickness of six inches, was poured onto the surface of the 100-foot-wide track. Cars on this vast new circuit could race ten abreast at 120 miles per hour.

When Brooklands opened in June 1907, it attracted plenty of attention.

But attendance at race meetings rarely approached the venue’s thirtythousand-strong capacity. After a while a new group of motor enthusiasts began to come forward, and there was a growing interest among the public to watch them at work. Britain’s pioneer aviators needed somewhere to build and fly their aeroplanes. They needed wide, open, level ground. For taking off, they wanted three-quarters of a mile of turf as smooth as a tennis pitch. For landing, the ground did not need to be perfect, but there needed to be a lot of it, and no trees. And they would require hangars. Small wooden sheds would suffice—they just needed somewhere to keep their tools and their small, fragile aircraft and, for those aviators hard up for funds, somewhere to bed down at night. In 1909, ground at the western end of the racetrack was flattened for the new flying village. Sheds began to go up; the fi rst aviators moved in.

It was eight years since Queen Victoria had died. Her sixty-three-year rule had seen the world transformed. Now, in Edward’s reign, everything seemed to be changing again; society’s established structures seemed to be fracturing. Britain’s Labour Party, formed to give voice to the working class, had been founded in 1900, in Victoria’s fi nal year. Rising demands for women’s suff rage had been catalysed by the formation in 1903 of Emmeline Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union, which embarked on a militant campaign against the establishment. In Russia, the 1905 revolution was still convulsing. Old ways were clinging on, but modernity was washing in relentless waves over societies worldwide. The future no longer belonged only to landowners like the Locke Kings. Opportunities for advancement and fortune were opening to those born without privilege. Brooklands, despite its establishment beginnings, was destined to become one of those extraordinary locations where egalitarian innovation flourishes—a place that attracts those who want change. It could be a thrilling place. One visitor described “the immense flat plain of the flying ground bounded by the motor track which shuts out all other view and forms the horizon, so that one feels as one imagines a fly might feel if he found himself set down on a green silk table-spread with a white border.” The flying displays put on by the pioneer aviators—those who were self-taught or who had been taught overseas—attracted huge

crowds, much bigger than the motor races. Spectators would line the top of the racetrack banking to get a glimpse of this exotic new activity.

Soon, the amateurs and enthusiasts were joined by business-minded aviators who set up flying schools. The first was founded in 1910 by Hilda Hewlett and Gustav Blondeau. Hewlett had been born, as Hilda Herbert, into a stifl ing middle-class family in south-west London. Her claustrophobic upbringing transformed into a marriage to Maurice Hewlett, a poet and historical novelist. But the partnership had eventually run its course and was falling apart. Searching for escape, Hewlett witnessed her fi rst aeroplane fl ight in 1909, at Blackpool, when she was forty-five. She later remembered, “I was rooted to the spot in thick mud and wonder and did not want to move. I wanted to feel that power under my own hand and understand about why and how.” When she told her family about her newfound ambition to fly, she was met only with scorn. Her husband, the poet, insisted that women were unsuited to aviation because they didn’t have the nerve. It was just, he said, “a passing and silly escapade.” But Hewlett prophesied a different future. “The time will come,” she said, “when every woman who can drive her own car will also pilot her own aeroplane. All women can begin on an equality with men in the study of aeronautics as it is a new science, and it is delicate and exacting work for which they are quite fitted.”

The school’s fi rst pupil, thirty-five-year-old Maurice Ducrocq, signed up in August 1910. Two months and twenty-one lessons later, Ducrocq passed his pilot’s certificate. He was full of praise for the way Hewlett and Blondeau taught him. In fact, he was so inspired by the Brooklands experience that he set up his own aviation business there. He occupied a shed next to another newly formed flying school, run by a company known as Avro.

By 1912 the flying village had grown to a settlement of forty wooden hangars, fi lled with activity. There was the buzzing rasp of thirsty and capricious piston engines. The sensation of speed and power pervaded the place. There would be the shadow of an aeroplane lurching overhead and shouts of encouragement from other aviators. Then there would be shouts of frustration as a take-off or a landing would go wrong. Often,

there would be a forced drop into the sewage farm next to the sheds. The owners of Weybridge and Byfleet boarding houses soon got used to laundering fi lthy overalls. It was a world apart from the rest of British society, where everybody knew their place and kept to it. The flying community at Brooklands became a place where the gentry mixed with the proletariat. Women and men worked side by side. Teenagers could chat as equals with their elders. Britons rubbed shoulders with aviators from overseas. They all came together at the airfield’s café-restaurant, the Blue Bird, where they discussed their problems and pored over the latest copies of flying magazines while smoking cigarettes, eating bread and jam, and drinking endless cups of tea.

On the cool autumn morning of October 24, the fog that enveloped Brooklands soon started to burn off, and there was barely the whisper of a breeze that day. Bad weather and bad luck earlier in the week had thwarted Harry Hawker’s bids for the Michelin prize. He had already been up in his Sopwith biplane three times. On his fi rst fl ight, a valve

spring in his hard-working engine broke after he had been three and a half hours in the air. High winds put paid to the second attempt, despite his endeavours to get above the gusts by ascending to 2,000 feet. The aircraft was tossed around like an out-of-control kite, 200 feet up and down each time. He struggled to keep hold of the controls. There was no way he could have hung on for longer. The following day, his third try was ended by a heavy rainstorm. The water got into the magneto, which created the engine’s ignition sparks, and short-circuited it.

Yet, as the sun rose over the airfield that Thursday morning and pushed the fog aside, all these tribulations were behind him. Hawker assumed he would be making the attempt for the prize on his own that day. It would be fourth time lucky, he told himself, as mechanics pulled the wooden shutters from the Sopwith hangars, lit the braziers to fend off the autumn chill, and set to work preparing the aeroplane. Then his friend Fred Raynham had turned up two doors down at the Avro shed.

FREDERICK RAYNHAM, KNOWN TO MOST AS FRED, WAS A TALL nineteen-year- old with dark, straight hair combed into a neat parting, and a long, youthful face that could have made him a movie star. He was a cheerful young man, though people noticed an air of reserve about him. One friend later observed, “His carefree looks hid a careful thoughtful character.” There was an edge of steel to his personality as well. As the son of Suffolk tenant farmers, born in 1893, he had been just two years old when he lost his father to tuberculosis. The thirtytwo-year-old James Raynham had been staying at a treatment hotel in Davos, a town high in the Swiss Alps whose pure, frigid air made it a mecca for those suffering from lung ailments. But an Alpine convalescence failed to save him. His death left his thirty-year-old wife, Minnie, to bring up Fred and his older sister alone.

The tragedy of their bereavement could not have come at a worse time. British farming in the 1890s was on its knees, and Suffolk was the county suffering by far the worst in the agricultural depression. Grain prices had fallen through the floor. The American prairies had been put under mechanized cultivation, and railways and steamships slashed the cost of transporting the harvest overseas. American wheat flooded European shores. Under the policy of free trade, Britain’s cereal farmers could not compete. Agricultural workers from Suffolk and elsewhere had been fleeing in droves to the industrial cities to fi nd work, leaving rural populations hollowed out.

For many of those left behind, prices had fallen so low it just wasn’t worth cultivating the land: it cost more to grow the crop than it fetched at market. Some tried to switch to dairy farming, but their desperate condition meant that investment in new machinery and stock was difficult to secure. Change was hard and slow: too hard and too slow for many. Surviving records suggest that James and Minnie Raynham managed to navigate the worst of the depression and switched to livestock farming before James’s failing health had overtaken him. Those who couldn’t make ends meet simply abandoned their land. A government investiga-

There was grinding, dispiriting poverty all around, and there didn’t seem to be any way out of it for those on society’s bottom rung. Two reformers, writing twenty years after Fred Raynham’s birth, described the hopelessness that still hung over the poorest workers in rural Britain, whose earnings kept them alive and little more. Their poverty trapped them in a hollow existence. “It means,” wrote the reformers, “that people have no right to keep in touch with the great world outside the village by so much as taking in a weekly newspaper. It means that a wise mother, when she is tempted to buy her children a pennyworth of cheap oranges, will devote the penny to flour instead. It means that the temptation to take the shortest railway journey should be strongly resisted. It means that toys and dolls and picture books, even of the cheapest quality, should never be purchased; that birthdays should be practically indistinguishable from Fred Raynham in 1911, aged seventeen or eighteen.

tion in 1895, the year James Raynham died, heard from one expert witness that “Suffolk can be given away to anybody who will take it. . . . The future is about as black as can be.”