ATWOOD MARGARET

Book of Lives A Memoir of Sorts

book of lives

non- fiction

Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature Days of the Rebels: 1815–1840

Second Words: Selected Critical Prose, 1960–1982

Strange Things: The Malevolent North in Canadian Literature

Negotiating with the Dead: A Writer on Writing (republished as On Writers and Writing)

Moving Targets: Writing with Intent, 1982–2004

Curious Pursuits: Occasional Writing, 1970–2005

Writing with Intent: Essays, Reviews, Personal Prose, 1983–2005

Payback: Debt and the Shadow Side of Wealth

In Other Worlds: SF and the Human Imagination

Burning Questions: Essays and Occasional Pieces, 2004–2021

novels

The Edible Woman Surfacing Lady Oracle Life Before Man Bodily Harm

The Handmaid’s Tale Cat’s Eye

The Robber Bride Alias Grace

The Blind Assassin

Oryx and Crake The Penelopiad

The Year of the Flood MaddAddam

The Heart Goes Last Hag-Seed

The Testaments

shorter fiction

Dancing Girls

Murder in the Dark

Bluebeard’s Egg

Wilderness Tips

Good Bones and Simple Murders

The Tent

Moral Disorder

Stone Mattress

Old Babes in the Wood

poetry

Double Persephone

The Circle Game

The Animals in That Country

The Journals of Susanna Moodie Procedures for Underground

Power Politics

You Are Happy Selected Poems: 1965–1975

Two-Headed Poems

True Stories

Interlunar

Selected Poems II: Poems Selected and New, 1976–1986

Morning in the Burned House

Eating Fire: Selected Poetry, 1965–1995

The Door

Dearly

Paper Boat: New and Selected Poems, 1961–2023

graphic novels

Angel Catbird War Bears

for children

Up in the Tree

Anna’s Pet (with Joyce Barkhouse)

For the Birds

Princess Prunella and the Purple Peanut

Rude Ramsay and the Roaring Radishes

Bashful Bob and Doleful Dorinda

Wandering Wenda and Widow Wallop’s Wunderground Washery

BOOK OF LIVES

A MEMOIR OF SORTS

MARGARET ATWOOD

Chatto & Windus

london

Chatto & Windus, an imprint of Vintage, is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies

Vintage, Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW

penguin.co.uk/vintage global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published in Great Britain by Chatto & Windus in 2025 First published in Canada by McClelland & Stewart in 2025 First published in the United States of America by Doubleday in 2025

Copyright © O. W. Toad Ltd 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781784744496

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

For my family, friends, and readers

And for Graeme, as always

You were such a sensitive child!

— my mother

But I’m quite inty now.

— me

Yes. You are.

— my daughter

One of these days that smart mouth of yours is going to get you in trouble.

— my father, when i was a teenager

She would have made such a ne Victorianist.

— jerry buckley, my thesis adviser

If she’d never met me, your mother would still have been a successful writer, but she wouldn’t have had as much fun.

— graeme gibson, my partner, to our daughter

Don’t piss her o , or you will live forever.

— julian porter, my friend

CONTENTS

Introduction d xiii

CHAPTER 1 d Farewell to Nova Scotia d 3

CHAPTER 2 d Bush Baby d 15

CHAPTER 3 d Gemini Rising d 20

CHAPTER 4 d Mischie and d 38

CHAPTER 5 d Cat’s Eye, e Prequel d 59

CHAPTER 6 d Hallowe’en Baby d 76

CHAPTER 7 d Synthesia d 84

CHAPTER 8 d First Snow d 105

CHAPTER 9 d e Tragedy of Moonblossom Smith d 117

CHAPTER 10 d Snake Woman d 124

CHAPTER 11 d e Bohemian Embassy d 137

CHAPTER 12 d Double Persephone d 155

CHAPTER 13 d e Handmaid’s Tale, e Prequel d 165

CHAPTER 14 d Up in the Air So Blue d 181

CHAPTER 15 d e Circle Game, e Prequel d 194

CHAPTER 16 d e Edible Woman d 205

CHAPTER 17 d Alias Grace, e Prequel d 222

CHAPTER 18 d e Animals in at Country d 232

CHAPTER 19 d Graeme, e Prequel: Part One d 248

CHAPTER 20 d Surfacing d 262

CHAPTER 21 d Graeme, e Prequel: Part Two d 286

CHAPTER 22 d e Edibles d 296

CHAPTER 23 d Graeme, e Prequel: Part ree d 311

CHAPTER 24 d Survival d 318

CHAPTER 25 d Monopoly d 336

CHAPTER 26 d Lady Oracle d 352

CHAPTER 27 d Days of the Rebels d 371

CHAPTER 28 d Life Before Man d 392

CHAPTER 29 d Bodily Harm d 409

CHAPTER 30 d e Handmaid’s Tale d 429

CHAPTER 31 d Cat’s Eye d 446

CHAPTER 32 d e Robber Bride d 457

CHAPTER 33 d Alias Grace d 467

CHAPTER 34 d e Blind Assassin d 478

CHAPTER 35 d e MaddAddam Trilogy d 487

CHAPTER 36 d e Testaments d 514

CHAPTER 37 d Dearly d 536

CHAPTER 38 d Old Babes in the Wood d 544

CHAPTER 39 d Paper Boat d 551

Becoming an Entomologist (by Carl E. Atwood) d 555

Acknowledgements d 563

Credits d 571

Chronological List of Books d 573

Index d 575

I almost expected to see my doppelgänger sprinting across town pursued by a mob, but I guess things didn’t work that way.

— ransom riggs, miss peregrine’s home for peculiar children

Some years ago, I was asked to make a stunt appearance on a comedy show. e host, Rick Mercer, was doing a series in which people well known for one kind of accomplishment, such as writing, astonished viewers by doing something di erent and entirely unrelated, such as rolling a joint.

“I want you to be a hockey goalie,” Rick said.

“Oh, I don’t think so,” I said. “Couldn’t I just maybe bake a pie or something?”

“No. You gotta be a goalie.”

“Why?”

“Because it’ll be funny. Trust me.”

So I was a goalie, in a full set of pads, with gloves and a stick. ere I am on YouTube, still goalie-ing it up; and yes, it is kind of funny.

I wore my own little white gure skates with black socks over them to make them look like hockey skates. But you can’t slide and stack the pads in gure skates, so those feats were performed by a body double—an accomplished women’s hockey player. With her face mask on, you can’t tell that it isn’t me. It’s the job of the body double

to take the risks you yourself are too sedate or chicken or unaccomplished to take.

I wish I could have a body double in my real life, I thought. It would come in so handy.

Of course, I do have one. Every writer does. e body double appears as soon as you start writing. How can it be otherwise? ere’s the daily you, and then there’s the other person who does the actual writing. ey aren’t the same.

But in my case, there are more than two. ere are lots.

Some months a er my sixth novel, e Handmaid’s Tale, had been published, I was doing a book event to promote it. During audience question time—with open mics, which many folks present used to deliver sermons—a man gave his opinion.

“So, e Handmaid’s Tale is autobiography,” he said. It wasn’t a question.

“No, it’s not,” I said.

“Yes, it is.”

“No, it’s not. It’s set in the future,” I said.

“ at’s no excuse,” he said.

He was wrong, needless to say. Within my own lived experience, I had not donned a red out t and a white bonnet and been coerced into procreating for the top brass of a theological hierarchy. But in a very broad sense, he was right. Everything that gets into your writing has gone through your mind in some form. You may mix and match and create new chimeras, but the primary materials have to have travelled through your head. Is “autobiography” only a series of events that have happened to you in the physical world, or is it also a record of an inner journey? Is it like Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (here’s how I made my hut), or is it more like Newman’s Apologia Pro Vita Sua (here’s why I changed my faith)?

When the idea of writing a “literary memoir” rst sprang up (from whom? Memory shrugs, but it was someone in publishing), I replied to her, or him, or them: “ at would be tedious. You’ve heard the bad joke about the old East Coast sherman counting sh? ‘One sh, two sh, another sh, another sh, another sh . . .’ So, my ‘literary

memoir’ would go, ‘I wrote a book, I wrote a second book, I wrote another book, I wrote another book . . .’ Dead boring. Who wants to read about someone sitting at a desk messing up blank sheets of paper?”

“Oh, that’s not what we meant!” they said. “We meant a memoir in, you know, a literary style!” is was even more ba ing. What would that be like? Eighteenthcentury mock-heroic couplets?

Lo, when Dawn’s rosy ngers do the curtains part, Down sit I at my desk to labour at mine Art.

Or something more in the Gothic amboyant style of, for instance, Poe?

A thousand brightly hued images whirled within my dizzied brain, and menacing phantoms thronged the shadowy corners of my tapestried chamber. In a frenzy I seized my enchanted quill, and ignoring the large blot of ink now taking demonic shape on the dazzling sheet of snowy parchment before me, I . . .

No, it would not do.

One of the rst interviews I ever did with a newspaper reporter was in 1967. I had—much to my surprise, as well as everyone else’s— just won the only major literary prize in Canada at that time, the Governor General’s Award, for my rst collection of poetry, e Circle Game. I was living in Cambridge, Massachusetts, studying for my Ph.D. at Harvard. A Canadian newspaper decided it had better acknowledge my prize-winning, and had directed a war reporter on his way back from Vietnam to do an interview with me. I expect his friends made relentless fun of him. Interviewed any more girl poets lately?

I had on a red minidress and shnet stockings. e reporter wasn’t wearing a ak jacket, but he might as well have been. We sat in a café. He looked at me. I looked at him. We were both at a loss.

Finally, he said, “Say something interesting. Say you write all your poetry on drugs.”

Is this the kind of thing that would be expected of me in a literary memoir? Alcoholism, debauched parties, drug-taking, agrant sexual transgressions, with the writing itself treated as a by-product that had oozed or sprouted from the compost heap of my outrageous behaviour? But that wasn’t how I’d spent my time, or most of it.

“I think maybe not,” I said to those who’d made the literary memoir suggestion. Or did I say it to myself? In any case, the important word was not.

Time passed, however, and the idea of a memoir acquired a lurid phosphorescent glow. Wasn’t there something appealing in the idea? my sinister alter ego whispered. I could depict myself in a attering light, casting a gauzy haze over my stupider or wickeder actions while blaming them on others. At the same time, I could thank my benefactors, reward my friends, trash my enemies, and pay o scores long forgotten by everyone but me. I could spill some beans, I could dish some tea.

A er he’d published Fi h Business in 1970, when he was almost sixty, the novelist Robertson Davies was asked why he’d waited so long to resume novel-writing a er his early comic successes. His answer was two words: “People . . . died.”

It’s true. People die, and a er they do, things may be said about them that might have been held back before. But—I told myself— I wouldn’t have to con ne myself to this kind of squalid moral bookkeeping. I could embark on a journey in search of my own authentic inner self, supposing there is such a thing. At the very least, I could examine the many images of myself that have materialized and then vanished over the years, a few concocted by me, but many—less positive and sometimes downright frightening—projected onto me by others. I have been asked some very strange questions. “Why is your mouth so small?” one letter-writer queried. “Why are there so many bottles in your work?” I was asked at a reading, “Is your hair really like that, or do you get it done?” One of my favourite questions, posed in a gymnasium a er a reading in a small town in the Ottawa Valley, where no living writer had ever been before.

In some variants of myself, I terrify interviewers; in others, I cause

pathetic whining in politicians. One glance from my baleful eyes and strong men weep, clutching their groins, lest I freeze their gonads to stone with my Medusa eyes.

My Medusa eyes go with my Medusa hair, which used to be referenced in book reviews, back when invective was more uninhibited and body-shaming was the norm, especially when men were reviewing women. A scary thing, curly and/or frizzy and/or Pre-Raphaelite hair; and if you wore it down, how unruly and indeed demented you must be—a descendant of all those nineteenth-century female literary creations who wandered the countryside or jumped o castle roofs, or earlier ones like Ophelia who oated down rivers, crazy as bedbugs, tresses rippling. No wonder female writers of earlier generations went in for tight buns and—later—carefully varnished cold waves.

Witches, of course, unbound their hair in order to cast spells, unleash tornados, and seduce men: perhaps some of these beliefs lingered among male cultural commentators of the mid-twentieth century, and contributed to my witchy reputation. Or the connection may be le over from the 1950s and early 1960s, a time when a female person who wrote anything but the ladies’ pages was considered not only unnaturally powerful but a borderline lunatic. Or maybe it comes from the early 1970s, in which energetic language from females was equated with bra-burning, man-knackering, and other unfeminine pursuits. e novelist Margaret Laurence—from an earlier generation—used to complain that because she had children, she wasn’t treated as a serious writer but as an ino ensive cookie-baking mum: “just a housewife.” I, on the other hand, found myself making the opposite protest: when I wasn’t ying through the air in the shape of a bat, I would declare that I could turn out a decent Christmas cake and knit a few sweaters while I was at it. is is a very old dichotomy: on the one hand, a woman doing woman stu ; on the other hand, a serious writer with a knife up her sleeve.

“She writes like a man,” a fellow poet said of me in the early 1970s, intending a compliment.

“You forgot the punctuation,” I told him. “What you meant was, ‘She writes. Like a man.’ ” Ripostes of this kind came in handy at the time.

If I embarked on this memoir venture, I mused, I could scrutinize these various images, plus a few others not usually considered. Am I at heart the ringleted, tap-dancing moppet of 1945? e crinolined, saddle-shoed rock ’n’ roller of 1955? e studious budding poet and short-story writer of 1965? e alarming female published novelist and part-time farm-runner of 1975? Or the version possibly most well known: the bad typist beginning e Handmaid’s Tale in Berlin, nishing it in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and then publishing it, to mixed reviews, in 1985?

Other renditions of me have followed. As the years pass, I have waxed and waned in the public view, though growing inevitably older. I have dimmed and ickered, I have blazed and shot out sparks, I have acquired saintly haloes and infernal horns. Who would not wish to explore these funhouse mirrors?

Perhaps I am a liminal being, partaker of two natures, guardian of thresholds, shapeshi ing almost at will; a sort of Baba Yaga, sometimes benevolent, sometimes punitive, dwelling in a woodland hut that runs around on chicken legs, propelling my way in a mortar with a pestle for an oar, humming a cheerful though somehow menacing tune.

In my case the tune is most likely the dwarfs-marching-to-work song from the Disney lm Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, which traumatized me as a child. It’s sacred to short workaholics, of which I am one, but the trauma came from elsewhere: I was petri ed at the age of six by the transformation scene, in which the good-looking queen drinks a magic potion, turns green, and morphs into a warty old hag. How horrifying, yet how essential! e pretty, tuneful Snow White is acted upon, but she doesn’t act; it’s the wicked queen who has the best scenes. Every writer knows this is the truth. And every writer also knows that without the wicked queen, or her avatars— the alien invasion, the hurricane, the marriage-breaker, the sinister assassin, the snakes on a plane, the killer in the country house—there is no plot.

Every writer is at least two beings: the one who lives, and the one who writes. Every question-and-answer session at a book event is

an illusion; it’s the one doing the living, not the one doing the writing, who is present on such occasions. How could the writer be there, since no writing is being done at that moment? Like Jekyll and Hyde, the two share a memory and even a wardrobe. ough everything written must have passed through their minds, or mind, they are not the same.

e one doing the writing has access to everything in the memory bank. e one doing the living might have some idea of what the writing self has been up to, but less than you’d think. While you’re writing, you aren’t observing yourself doing it, because if you start studying your so-called process while in full ight, you’ll freeze.

Is writing a trance state, as Coleridge’s story about his writing of “Kubla Khan” might suggest? Not quite: you can break o , go for a co ee, answer the phone, show every sign of normality. Or I can. Yet the sensation of something else taking over can’t be ignored; too many writers have testi ed to it. Flow state, inspiration, characters seizing the initiative from their authors, dream visions, out-ofbody experiences—these kinds of testimonies are too numerous to be dismissed.

On top of that, perhaps there are (at least) two models of writer: devotees of the lyre-strumming Apollo, highly conscious of structure and harmony, with his bevy of Muses; and those who call instead upon Hermes, god of tricks and jokes and messages, concealer and revealer of secrets, patron of travellers and thieves, conductor of souls to the Underworld. If you’re doing a revision of a dra , you need Apollo; if you’re stuck mid-plot, you might invoke Hermes, opener of doors, though there is no guarantee about what might lie behind that door. at the two gods are joined at the hip is evident in their mythic origin stories: it was Hermes who made Apollo’s lyre in the rst place. Most cultures have a version of this duality, since both form and energy are needed for any work of art.

To this we might add Bacchus, god of wine, proponent of divine intoxication, dissolver of inhibitions. Quite a few writers have written while under the in uence of something or other. In my case it was ca eine.

Some writers are fond of talking about their “material.” Marian Engel, author of the novel Bear, was telling me about her damaging experiences as a young child, when she and her twin were put up for adoption: they’d been separated because her twin was violently attacking her. en she said, “Copyright.” Meaning: that was her material, not mine. She was writing about these early experiences of hers when she died.

But where does all the assorted “material” come from? It comes from what is loosely known as your life and times. ings happen to you, or you hear about them. Big things and small things. Some of them impact you, or stick to you. You can’t avoid the time-space you’re living in. Nobody can. Your writing will always be done in it and will be connected to it, even if your book is set on another planet or in another century. It cannot be otherwise.

So, inescapably, I’ll have to describe the features of my own timespaces if I wish to cast any light on this writing thing. Be prepared for descriptions of outmoded technologies, such as ice houses and milk cupboards, and for explanations of archaic social rituals, such as sock hops and going steady. Also for thumbnail sketches of fashions of the time, such as pantsuits, miniskirts, A-line dresses, and the Ethnic Look.

I move through time, and, when I write, time moves through me. It’s the same for everyone. You can’t stop time, nor can you seize it; it slips away, like the Li ey River in Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. Memories can be vivid though unreliable; diaries can distort. Nevertheless, each life has its own particular avours and textures, and I will attempt to evoke those of mine.

Because memoirs need to have photos, I’ve been going through the horde: my mother’s and father’s early twentieth-century albums, with the black-and-white snapshots stuck in it with the little corners— grandparents, great-aunts, vintage automobiles that were brand new then, horses, covered bridges. en the 1930s and 1940s: I appear, I roll around on the oor, I stand up, I grow hair, I sprout teeth. At age eight I receive a Kodak Brownie and take pictures of my cat wearing a bonnet, my brother wielding snowballs and making faces, anomalous trees, unidenti able children. Other albums provide shots of

high-school formals, graduations, amateur theatricals. My rst poetry readings.

en book-cover photos. More of those. Now things are getting literary. Next come the newspaper and magazine shots, some grainy, others glossy; in the latter I’m frequently not wearing my own clothes, since wardrobe stylists had now been invented. I treasure the memory of one photo shoot in which I was asked to take o all my black clothing and put on other black clothing in which I looked exactly the same. en there was the time I went to Finland and found myself sitting in the makeup room of a television station. Quick as a wink, my hair was being set in hot rollers in an attempt to atten it out: the Finns were not used to my kind of hair. ey must have been trying to keep me from embarrassing myself in public. ( ey weren’t the rst or last to make this attempt. Few have succeeded.) In more personal layers of pictures, there’s my own family, at many ages and stages.

It’s overwhelming, sorting out the blizzard of images. Whatever are we to do with it, this accumulation? I’ve managed to weed out the shots I inadvertently took of the oor, my feet, the inside of my purse, but the others . . . ey hover in the air, fading but still visible, small ickers of what was once lived. How cold was it that day, what did we have for lunch, were we happy?

As I revisit my writing past, I’ve been having strange dreams. I’ve been conversing with the dead: the benevolent dead, mostly. I’ve been unearthing my early and luckily unpublished writings, and mortifying myself by reading them. I’ve been trying to recapture my state of mind at the time. Wrong turnings, crinolines, abandoned plots, nylons with seams, canoes, lost loves. It’s all material. What will I make of it?

BOOK OF LIVES

FAREWELL TO NOVA SCOTIA

a thing my mother said:

my mother : Because our father’s name was Dr. Killam, kids at school used to tease us. ey’d say, “Killam, Skin’em, and Eat’em.”

me : Did they hurt your feelings? my mother : Pooh. I wouldn’t give them the satisfaction.

a thing my father said:

“How long would it take two fruit ies, reproducing unchecked, to cover the entire Earth to a depth of two miles?” (I don’t remember the answer to this, but it was a remarkably short time.)

Both my parents were from Nova Scotia. My father was born in 1906, my mother in 1909. Counting forward, you can see they would have been entering the job market just as the Great Depression of the 1930s was at its height. Coupled with that was the general decline of the Canadian Maritimes: Halifax had been a prosperous seaport in the nineteenth century, but then came the building of the railroads and the shi of the nancial gravitational centre, rst to Montreal, then Toronto. e city had a brief uptick during the First World War; later, a er my parents had le Nova Scotia, it was the staging area

for the Atlantic convoys due to its sheltered harbour. Some in Nova Scotia bene ted from American Prohibition in the 1920s and early 1930s. A brisk smuggling business had shing boats picking up booze from Saint-Pierre and Miquelon—French territory—and running it into the deep coves and estuaries of Maine. If Uncle Bill suddenly got a new roof on his barn, you didn’t ask him how he’d paid for it. But to pro t from that trade you had to have a boat. ose who didn’t have boats were out of luck.

A joke from that time: “What’s the chief export of Nova Scotia?” “Brains.”

During those years, many Nova Scotians moved west in search of jobs. My parents were part of that exodus.

All the Nova Scotians I’ve known have been universally homesick. I’m not sure why, but so it has been. Both of my parents always referred to Nova Scotia as “home,” causing some confusion for me as a child: If Nova Scotia was “home,” where was I living? In some sort of not-home?

Ours is a family shrub, not a family tree. If you have roots in the Maritimes and meet someone else with similar roots, you nd yourself picking your way through the shrubbery. Who was your father, who was your mother, grandfather, grandmother, from where, and so on, until you establish the fact that you are related. Or not. is can go on for some time.

So here’s the deep dive.

Nova Scotia, far from being uniformly Scottish in origin as the name might imply, was remarkably diverse. e Mi’kmaq lived there and still do, and are related to other Indigenous groups in New Brunswick and Maine. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Nova Scotia was one of the rst parts of what is now Canada to receive an in ux of Europeans. French explorers; and French settlers and farmers who called themselves Acadian in honour of the comparatively idyllic place they found themselves in; then New Englanders who’d been enticed by cheap land. Later came a number of people who had been on the losing side of the American Revolution. ese included the Free Blacks, who’d fought on the side of the British. Collectively,

these immigrants from the States were known as United Empire Loyalists. Some of these were entangled in our family shrubbery.

Just before the Loyalists came German and French Protestants who’d been welcomed by the British during the French and Indian War with New France. Catholic New France—including Vermont and New Brunswick and what is now Quebec—was raiding the Protestant New England colonies with the help of its Indigenous allies, and vice versa. New England had the help of the British Army, while the French colonies were not so well supplied. Finally, in 1759, General Wolfe took Quebec City and New France fell to Britain. e New England colonists had no more need of the British Army, and did not see why they should be so heavily taxed. Result: e American Revolution, no taxation without representation, over-investment on the American side by the French monarchy, French debt, then the French Revolution.

While the wars were going on, the British had wanted to stu as many Protestants as possible into Nova Scotia. One of these French Protestants joined our ancestral line. So did some Scots from the Highland Clearances in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, a period during which many small tenant farmers got turfed out of their age-old communities by their own clan chiefs. is was not only fallout from the defeat of the Scots in the 1746 Jacobite rising but was also a result of the spread of pro table sheep farming. I used to joke that I was descended from a long line of folks—going back to the Puritans, but not limited to them—who’d been kicked out of other countries for being contentious, or heretical, or indigent, or otherwise disagreeable.

Here are some of the names from the family shrubbery: Atwoods, Killams, Websters, McGowans, Lewises (from Wales), Nickersons, Moreaus, Robinsons, Chases. ose are just a few of the branches. If you go into the shrubbery, don’t get lost. It’s tangled.

e rst of my father’s family to reach Nova Scotia’s South Shore came from Cape Cod. Cape Cod is still crawling with Atwoods, descended from those who arrived in the early seventeenth century, either on the May ower or shortly a er it. ey clustered around Welleet, Massachusetts, and then Chatham. Several museums, including the Atwood Museum in Chatham, are well worth a visit—don’t miss

the cat door under the stairs through which a cat was stu ed every night to catch mice under the oor. (What did the house smell like? I wonder.) ere’s also a portrait of a later dentist Atwood, who got himself painted in formal dress with three sets of dentures set out in front of him of which he was evidently proud.

It was the younger brother of the museum’s original Atwood owner who went to Nova Scotia in 1758, landing in Shelburne, a small port on the south coast. From Shelburne, the Atwoods spread out, giving rise to several privateers operating out of Liverpool, to a number of sailors, and to some loggers and farmers.

By the time my father was born, his family was living at Upper Clyde, quite a distance from the coast up the Clyde River. My grandfather ran a little sawmill that made white pine shingles, cedar being almost non-existent in Nova Scotia. Stacking these shingles at age six was the rst of many jobs my father would hold. He enjoyed this immensely, according to him—children then being expected to contribute to the collective family economy as soon as they could.

e family would not have described itself as poor—they had a house, they had a cow, they had a parlour organ. My grandfather belonged to the Masons, which meant he must have been at least marginally respectable. But the family didn’t use money for as many things as people use it for today. If what was needed was something you could make—from wood, such as tables and chairs, or cloth or yarn, such as dresses, quilts, or mittens—you made it yourself. People got married, almost without exception. ere weren’t many jobs for spinsters, and everyone knew that a man would have a very hard time running a small farm single-handed: a wife was necessary.

My grandmother, who was my grandfather’s second wife, kept chickens and ran a vegetable garden. She had the Rolls-Royce of wood-burning kitchen ranges, with an oven, a warming oven, a hotwater heater, and chrome trim. She smoked her own sh, and made butter in a churn; as a child I helped her make some.

Seeing this way of life, unchanged since the nineteenth century, was very helpful to me when I was writing Alias Grace. My grandmother’s stove was much fancier than anything available to Grace

Marks, but the rhythm of the work and the shape of the days was much the same. My father, Carl, was the eldest of ve, unless you count Uncle Freddy, son of the rst wife. He was already grown up— a mysterious gure, lurking around the barn not saying much, and said to be not quite right in the head. e story we were told was that he’d been gassed in the First World War, but another informant said he’d already been like that. As with so many family stories, you don’t think to investigate them until there’s nobody le to ask.

Carl learned to read and write in a one-room schoolhouse. ere was no nearby high school, so he took his high-school classes by correspondence course, encouraged by my grandmother, who’d been a schoolteacher. His studies would have been in addition to his farm chores and his work as a teenager in the winter logging camps, something my grandfather had also done. It was in the logging camps that he picked up an extensive vocabulary of swear words, said my mother. She heard him use them only once, when he hit his thumb with a sledgehammer while sinking the sand point for a hand pump. “ e air turned blue,” she said with appreciation: here was a talent she hadn’t known he had.

Carl was very musical. I don’t know how he learned to play the ddle, but he did. His younger brother, Uncle Elmer, played the banjo, and the two of them would provide the music for the local Saturday-night square dances, which could get rough—liquor consumed, st ghts outside. As the musicians, the two of them could avoid all that. Carl could sing at that time too: he was said to have had a beautiful baritone voice. But a er he heard his rst professional concerts as a young adult, once he was well and truly on his way to being a scientist, he never sang or played the ddle again. My guess is that he tagged himself as an amateur. e furthest he would go was whistling: he was partial to Beethoven.

As a barefoot child walking from school, my father became fascinated by a giant green caterpillar he’d found, and it was this creature— the larval form of the cecropia moth—that drew his attention to the world of insects. He took the caterpillar home, made a little cage for it, fed it, and watched it transform, rst into a pupa and then into a huge and colourful moth. is was the initial step in the process that led eventually to his career as an entomologist. Had he not followed

this path he would never have met my mother and I would not have been born. So I owe my existence to a large green caterpillar.

One of Carl’s steps along the way was a stint at the normal school in Truro, where you were taught to be a schoolteacher. (I used to think it was where you learned to be normal, but this was not the case.) His intention was to teach school until he’d saved up enough money to get himself to university, but he was able to take a shortcut via summer jobs in entomology and a scholarship to Acadia University in Wolfville. From there he jumped via another scholarship to Macdonald College, the agricultural wing of Montreal’s McGill University, where he cleaned out rabbit hutches, lived in a tent and cooked for himself during the warmer months, and saved enough to send some money “home” so his three sisters could continue in school.

It was at the Truro normal school that my father rst saw my mother, who was sliding down the main banister. He vowed then and there that she was the woman he would marry. It took him two tries—she turned him down the rst time because she “was having too much fun”—but he managed it. He’d overcome so many barriers by then that he didn’t take an initial no as de nitive.

“He surprised me. I thought he was just a friend,” said my mother of his rst proposal. She had an abundance of swains and beaux swarming around, but my father was the only one who wasn’t pronounced “a jackass” by her father. He himself had pulled himself up by his bootstraps to become a doctor. Possibly he recognized in Carl—an extreme bootstrap-puller—something of himself.

My mother, Margaret Killam, was a tomboy and intensely athletic; hence the banister-sliding. Her background was quite di erent from my father’s: it was genteel-rural rather than backwoods-rural, from a tiny village called Woodville in Kings County. Kings was in the Annapolis Valley, much given to apple-growing.

My grandfather, Dr. Harold Killam, was the revered country doctor for the area. He helped found the Berwick hospital (since closed); he helped build the local Methodist church (since converted to a home). He was a First World War army doctor, and had been called to Halifax at the time of the Great Halifax Explosion in 1917 (almost

two thousand killed, nine thousand wounded). Our Great-Uncle Fred had been shot out the window and had landed, unhurt, on the sidewalk, still in his bed. Great-Aunt Rose, not so lucky, had fallen through the shattered oor into the cellar, and as a result had had a miscarriage.

My head was populated early by such tales—tales of people I didn’t know. ey had the status of semi-imaginary creations with largerthan-life stories attached to them, like Beowulf. More news of such beings would arrive every week: my mother and her two sisters wrote one another faithfully all their lives, and my mother would read the letters out loud to my father. She was the eldest of ve. e others were her “twin” sister, Kathleen or Kae, born less than a year later, her sister Joyce—four years younger than she was—and two younger brothers, Fred and Harold. Many of her stories revolved around this group. You never knew what the demigods in Nova Scotia would get up to next.

ere were lots of stories about my grandfather Dr. Killam: o in the middle of the night, driving his sleigh through the snow to deliver babies on kitchen tables, operating in his surgery—which was at the front of their house—on some poor man who’d chopped himself with an axe. “Don’t get sick,” my mother used to say. She’d seen and heard too much of what happened to sick people in the days before multiple vaccines and penicillin and advanced diagnostic tools.

Dr. Killam was a man of considerable local standing. As a respectable person, you couldn’t drink, smoke, or swear, not that my grandfather was inclined to do any of these things. He referred to cigarettes as “co n nails” long before research had proven him right.

As the daughter of the doctor, Margaret was expected to be up to snu both socially and intellectually, but she was somewhat rebellious. She and her father were frequently at odds; both were intent on getting their own way, and both had tempers. “We were too much alike,” she said. She was a speed skater as a teen. She was also horsemad, and cantered around on the backcountry roads on one or another of the two horses she was allowed to keep in the barn, one being a rescue horse she’d brought back from “skin and bones” to glowing health.

Margaret longed to ditch her luxuriant though bothersome hair,

but was refused permission by her autocratic father. (“He was stern, but he was Respected,” she would say.) She nally managed to get a 1920s bob by waiting until her father was in the dentist’s chair, writhing in pain—no anaesthetics then—before requesting permission once again. He said, in essence, “Anything, anything, just leave me alone!” And the deed was quickly done. Her “twin” sister, Kae, was studious, and my grandfather sent her to the University of Toronto, where she was the rst woman to get an M.A. in History. But my mother was viewed as a ibbertigibbet; her brain, said my grandfather, was just a little button holding her spine on. No university for her: it would be a waste of money, in his opinion.

Margaret took this as a challenge. O she went to normal school in Truro, attracting my father along the way. She taught in a oneroom schoolhouse for two years, riding her horse to and fro, saved up the money, and got herself to the Mount Allison Ladies’ College, in Sackville, New Brunswick. “Why did you go to Mount A., rather than to Acadia in Nova Scotia?” I asked her once. “It was farther away,” she said. I asked her—a er a spate of nostalgic anecdotes about “home”—why she had never moved back there. “Everyone knows your business,” she said. She had a point. At Mount A. she took Home Economics, not because she liked it but because it was the most plausible path to a job for a woman. In the background was a maiden aunt who helped her out. Margaret won a scholarship at Mount A. Take that, Respected Father! She’d demonstrated “gumption,” a desirable quality, and had practised self-su ciency, also desirable, and had shown that she wasn’t just a u -brain. (She was also climbing in and out of her dorm windows a er hours, but evidently she didn’t get caught.)

e Great Crash happened in 1929, when Margaret was twenty, and the Depression set in. Jobs were scarce. At some point my mother taught cooking in a girls’ reform school (“ ey used to drink the vanilla extract”), then became a dietician at the Toronto General Hospital, where she put on weight (“We used to eat the le over ice cream”). My father was studying at the University of Toronto; he pro-

posed again, and this time was accepted. ere was an interlude during which my mother had to go “home” to help out, as her father had su ered “a coronary.” Another mysterious term of my childhood: What was it, exactly? e cure was rest, not that rest was much of a cure. ere were no stents or heart transplants then. As visiting children, we did a lot of tiptoeing.

In 1935, my parents nally got married, in a double wedding. My Aunt Kae married a local doctor, having rejected a plan to be sent to Oxford, as she didn’t want to end up, like their legendary Aunt Win, a spinster—the inevitable fate of any woman who chose such a brainy career. My parents spent their honeymoon going by canoe down the Saint John River in New Brunswick, which was not yet a icted with dams. Carl taught Margaret to paddle—she’d never done it before—and to sleep in tents. Sleeping in a tent hadn’t been part of her childhood—too potentially disreputable, as it might cause talk— so she’d slept in one before the wedding, accompanied by a sister, in order to practise. She took to the outdoor life like a duck to water.

She told my younger sister, much later, that the rst year of her marriage was “like a holiday” a er the strenuous work life she’d been leading. Married women didn’t keep their jobs during the Depression. Having two incomes in a family was considered sel sh, so when you got married you automatically quit or were “let go” unless you were on the very top or the very bottom of the pay ladder. During this initial married period, Margaret taught herself to type so she could type Carl’s Ph.D. thesis. She did it on the same portable Remington—white letters on black keys with white circles around them—on which I was later to type my rst poems. e housekeeping was minor since they didn’t have a house, so she had time to indulge her athletic proclivities by skating on any available ice and marching around in parks.

country mice and city mice: a digression

Both of my parents were country mice at heart, though they could put on city mouse camou age when required. e metaphor dates back to one of Aesop’s fables that later spread all over Europe. It

became the subject of an illustrated kids’ book by Beatrix Potter, and is still being retold.

Neither the country mouse nor the city mouse appreciates the lifestyle of the other. e country mouse eats simple food, the town mouse luxuries. ey visit each other, but the country mouse is frightened by the erce cats and dogs that abound in the city, and says she prefers the peace and quiet of the country. e peace and quiet of the country is of course a fable itself. e country—if you are, for instance, a farmer—can be a very dangerous place, and was even more dangerous in the early part of the twentieth century. Cows might kick you, horses might bolt and scrape you o against the top beam of the barn door, a pig might eat you if you carelessly fell into its pen. House res caused by wood stoves, kerosene lamps, or candles were always a possibility. A tractor might ip over and crush you like a grape. e farmyard and outbuildings bristled with sharp and potentially lethal implements: saws, axes, picks, sledgehammers, and guns of various kinds. If you wanted a murder weapon, you wouldn’t have far to seek. In the woods, you could get squashed by a falling tree, torn apart by bears or trampled by a bull moose in rut, or trapped in a forest re. You could freeze to death in a blizzard, drown in a lake, or be struck by lightning—a primary fear of my childhood. Never go swimming when a thunderstorm is brewing. I’m telling you this for your own good.

How could the city compete when it came to danger? But it could: with car accidents that could smash you to bits; with lurking scoundrels and drunks who might leap out of the bushes upon you; with the horrors of dressing for fancy occasions—what to wear?—and going to parties—what to say? In the country, hell was likely to appear as an animal or a snowstorm. In the city, hell was other people. ough hell could be other people in the country too, according to my mother’s stories: mean folks could exist anywhere. ere were two distinct mindsets then: urban and rural. In the city, you were expected to be outgoing, glad-handing, easily sociable. You’d be interested in novelties, such as new lms or fashions or gadgets or technologies. But you’d be more likely to be scornful of other people’s quirks, and to belong to a social hierarchy that sneered upon those below it. You’d be less likely to know your neighbours, and less

interested in doing so. Money mattered; it mattered a lot. Country people might be regarded by you as rubes and hicks, superstitious and unscienti c, backward in their thinking.

In the country, you were reserved when meeting people you didn’t know and skeptical of boasts and displays of wealth. Being thought of as an honest, solid, competent, and handy person was more important than being thought of as a rich or smarty-pants one. If you acted above other people, you were brought down to size, usually with mockery. Self-su ciency was important: If your toilet was clogged— supposing you had one, rather than an outhouse—you couldn’t just call a plumber, because there wasn’t one. You’d get out your wrench. Naturally you had a wrench, and many other x-it tools. You’d help your neighbours when they had physical problems such as an illness or a house burning down, and they in turn would help you. You’d think it bad manners to show o , to snivel and complain, or to express emotions to excess, or even at all. Having some fun was acceptable, but having too much of it was frivolous. You’d know how to split wood and make furniture and fell trees, or—if female—scald and pluck a chicken, keep a ock of egg-laying hens, churn butter, manage the kitchen garden, make jam, knit mittens, hook rugs, sew quilts, and use up any le overs. You had a secret scorn for city folk who hadn’t learned these skills: they didn’t know their ass from their elbow and stepped in cowpats because they didn’t watch where they were going. You accepted eccentrics as long as they were known to you and as long as they were harmless. If you had to gut things such as sh, you just rolled up your sleeves and got on with it.

In the country you passed the time of day with anyone you met. It was a way of nding things out. Our father retained this habit, and it used to drive us kids a bit crazy. Into a gas station he would go to pay the bill while we waited in the car, and waited, and waited. He’d engage in conversation with all sorts of people while jingling the change in his pocket. If he didn’t believe what they were telling him, he would say, “Is that so?” or “You don’t say!” It wouldn’t have been country manners to contradict. I remember watching him while a man tried to convince him that beavers sucked the air out of logs and that was why the logs sank. “Is that so?” “You don’t say!” ( Jingle, jingle.)

Both my parents knew the country mouse patterns because they’d grown up with them. Inside the dinner jackets and fancy party dresses they could assume at will, they held the reserve and skepticism of the country mice; yet they had the curiosity of the city mice too. ey could switch back and forth between country and city with hardly any e ort, or so it appeared from the outside. My elder brother and I were similar hybrids.

BUSH BABY

In the fall of 1936, my parents were living in Montreal, where Carl had an entry-level teaching position at Macdonald College. ey were expecting a baby in February. ey were far from rich: they “didn’t have a bean,” as my mother put it. She used to divide my father’s paycheque into four envelopes: rent, utilities, groceries, and, if any was le over, entertainment. Entertainment might be a movie, or it might be a small box of Laura Secord chocolates. ey would cut each chocolate in two so they could both share all the avours.

Unbeknownst to themselves, their apartment was in the red-light district of Montreal. (No doubt it was cheap.) My pregnant mother must have been a curiosity to the local professionals as she hiked briskly along the streets—she was always a great walker, pregnant or not—but, according to her, nobody ever “bothered” her. (If they had, she would have given them “what for.” “What for” was vague, but you wouldn’t have wanted to be on the receiving end of it.)

My brother, Harold, was born in the Montreal General Hospital the day a er Valentine’s Day, thus perfect for future birthday-cake decorating. is was before subsidized health care, so they wouldn’t let you out of the hospital until the bill had been paid. My father pawned his fountain pen to bail my mother out. at fountain pen itself is a mystery: it must have been expensive enough to merit pawning; it was probably a gi , as he wouldn’t have had enough beans to buy such a thing himself.

Tending to a baby in a small apartment must have been interesting. ere were no disposable diapers then; our mother soaked the

diapers in the toilet. ere was at least one plumbing emergency caused by premature ushing, and the diamond came out of Margaret’s engagement ring and was swept away. How did she do the rest of the wash? Possibly in a wringer washer. And she would have had an icebox and an electric iron. I know they had a toaster and a wa e iron—wedding gi s—because both were still in operation during my childhood.

en our father suddenly took a job with the federal government’s Department of Agriculture as an entomological eld researcher. is would involve seven months in a remote part of the northwestern Quebec forest. With a baby no more than a few months old, was Margaret up for such a thing? Yes! It was the prospect of exactly such adventures that had sealed the deal with my father in the rst place.

Di erent eras have di erent ideal marriage models for women.

e High Victorian model was the Angel in the House; the Second World War model was Keep the Home Fires Burning crossed with Rosie the Riveter; and the 1950s model was Little Wifey in a Shirtwaist Dress and Four Kids crossed with Station-Wagon Supermarket Grocery Shopper and Home Appliance E ciency. e 1930s model was what I call the Amelia Earhart: athletic ability and risk-taking weren’t considered unfeminine, resourcefulness was good, it was ne to wear slacks, lying on a sofa in a negligée eating chocolates was passé, and palship was valued. (Nancy Drew, the young woman detective with a car of her own, rst appeared in 1930.)

Our parents viewed their marriage as a partnership; Margaret was half of every major decision. Before their move to the bush, our parents made a pact: in the o en chilly woods, he would get up rst and cook the breakfasts; in the city, she would cook the breakfasts. In the early years this worked in her favour because they were up in the woods for at least two-thirds of every year.

For the new Department of Agriculture job, they moved to Ottawa with their tiny baby. Ottawa, the capital of Canada, was at that time a small provincial city. However, it did have one museum in which my brother—several years later—saw his rst dinosaur exhibits. Much impressed, Harold went home and made a plasticine dinosaur. It had an udder—a source of delight to my mother, who shared the news with her sisters via her weekly letter. Ottawa hadn’t been chosen as

the capital for its climate—it’s the second-coldest capital city in the world, the rst being Ulan Bator—but for its location on the Ottawa River, which marks the division between Ontario (largely Englishspeaking) and Quebec (where French predominates). For Canada, as a confederation with two o cial languages, this location made sense. e eld station where our father would do his research was also in border country, but on the Quebec side and over three hundred miles to the north. People there could communicate in “franglais,” a mixture of French and English. My father learned to speak franglais, of considerable use to him during his scienti c travels in northern Quebec. Anything you didn’t know the name for was la machine: helpful if ghting a forest re, which all adult males in the re’s vicinity were expected to do. You don’t worry too much about grammar when there’s a aming tree about to fall on you.

into the woods

For their rst stint in the northern forest—which began in May 1937—our parents and their three-month-old baby reached their location by narrow-gauge railway, since there wasn’t yet any road.

e site chosen for Carl’s lab was at some distance from a tiny assemblage of dwellings clustered around the railway stop. at rst summer, the little family lived in tents while my father and his crony from the village, Adrien Denis, began to construct the lab building. It was made mostly out of logs, and had a screened porch.

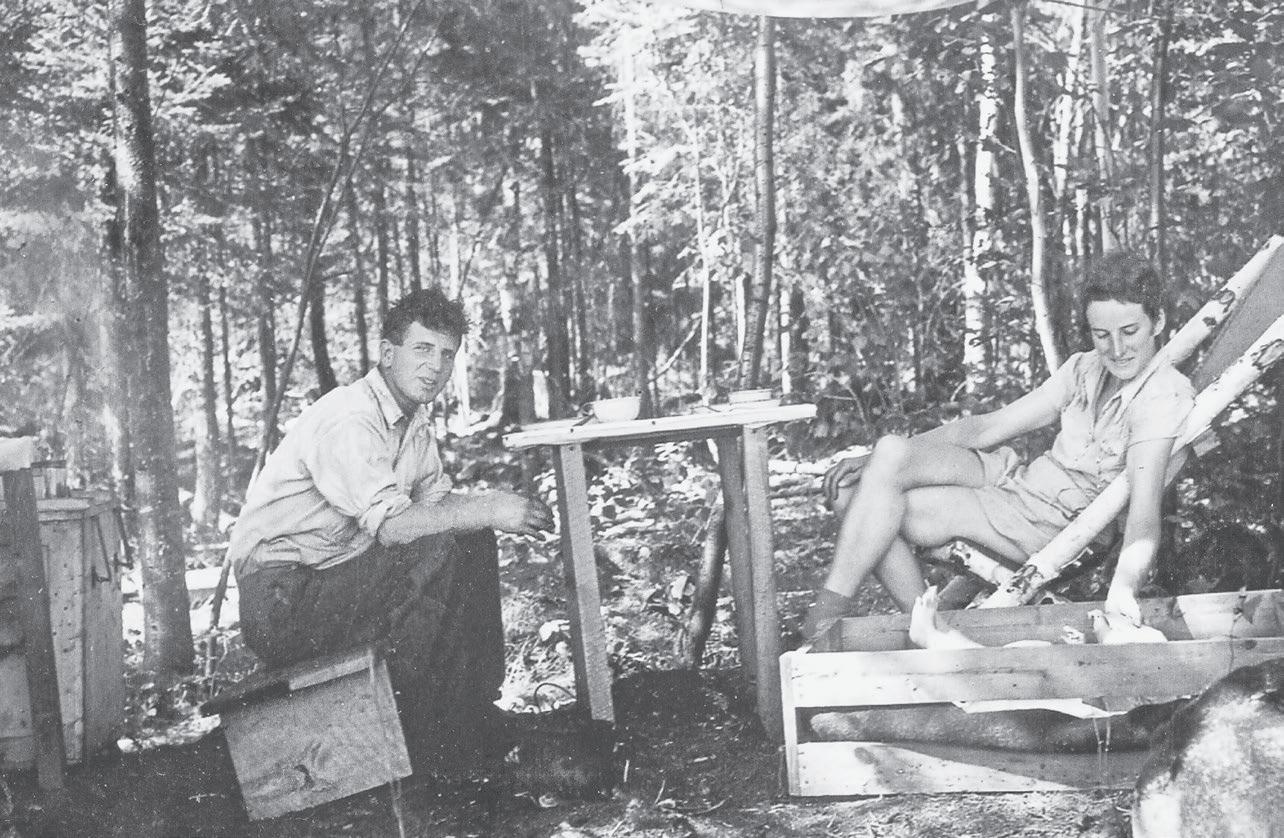

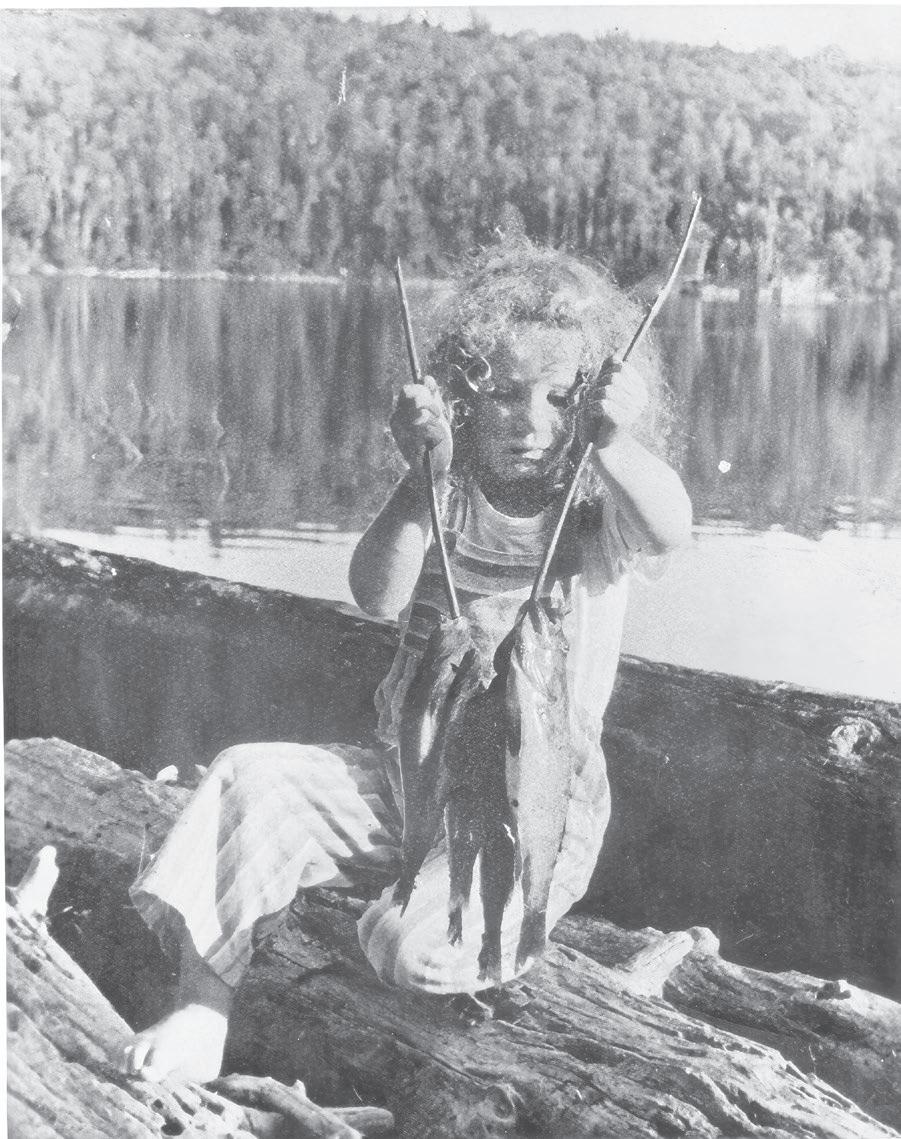

ere’s a picture of the three of them—Carl, Margaret, and Harold—in their woodland setting, looking pleased. Or at least the two grown-ups are. e baby’s expression can’t be seen: only his hands and feet are sticking up out of what looks like a packing crate. Our parents used to cover it with cheesecloth to keep out the mosquitoes and black ies.

Margaret is sitting in a deck chair made of birch poles—a Carl creation—with Carl himself on a stool constructed from another packing crate with a board nailed across it. Overhead is an awning or y, to protect this dining area if it rained, which it did o en, since the region was a northern rainforest. Rain or shine, you never ate inside tents. You didn’t want any animals or insects invading in search of crumbs, nor did you want any soup on the bedding.

ere’s also a photo of Carl rolling up an in atable rubber mattress. ey could have slept on one of those or on a spruce-bough mattress, but most certainly in sleeping bags, which, in those days before synthetics, would have been heavy and lled with kapok. Flannelette sheets inside the sleeping bags. Red-and-black-striped Hudson’s Bay wool blankets on top.

e little creature in the packing crate was thoroughly at home in the bush. He was a bush baby, you might say. Before he could even crawl, he was discovered during an insect infestation clutching a stful of forest tent caterpillars and about to eat them. When he grew up, he became a biologist. How could that possibly have been avoided? When it got cold and the insects were dead or hibernating, the family went back to Ottawa. How did this semi-nomadic plan work in practice? Did our parents put their furniture into storage for half

the year and take short-term apartment leases for the other half? ey couldn’t have a orded an apartment that they lived in for only half a year. Or did they sublet? In the spring, summer, and fall of 1938, they were back in the Quebec bush. e insect lab was completed and a small cabin built farther down the lake. Our parents moved into this cabin while Carl planned a larger house and constructed an outhouse, a woodshed, and an ice house. e land would have been secured through an inexpensive ninety-nine-year lease—the Quebec government was not making any outright sales then.

In the summer of 1939, a big outbreak of spruce budworm occupied much of my father’s attention. at was also the summer they almost lost Harold. He fell o the dock at age two and a half, having escaped from the chicken-wire play yard that enclosed a sandbox: our mother was a big believer in letting children play by themselves. Luckily, she had glanced out the window and seen that Harold was gone. She ran down to the dock, heard a bubbling sound, looked into the water, saw him sinking, and hauled him up by the hair. Narrow escape! (Our mother’s stories had a number of narrow escapes in them. We hung by a thread.)

Meanwhile, as the summer wore on, the international situation was getting tenser by the week. Just over the horizon—actually, just over the Atlantic—war clouds were gathering. e coming storm was about to break, changing everyone and everything in its path.

And I was about to be born.

(Ominous music. You may apply this either to the Second World War or to my birth, whichever you nd more tting.)

GEMINI RISING

IIappeared in the Ottawa General Hospital on the 18th of November 1939. On the face of it, you wouldn’t think this would be a propitious birthdate. It was two and a half months a er the onset of the Second World War, so my mother was probably full of anxiety chemicals before my birth. It was also the gloomiest month of the year: dead leaves but no snow, the daylight shrinking but no Christmas yet. It’s the month of death, sex, and regeneration, say the astrologers. ey must have thrown in the last two to sweeten the pill. November’s festivals are the Day of the Dead and Remembrance Day, which is another kind of Day of the Dead. Gloom all round. Given these negative auspices, why did I turn out to be such a cheerful infant? Because I was. ere are witnesses. Or there were.

appeared in the Ottawa General Hospital on the 18th of November 1939. On the face of it, you wouldn’t think this would be a propitious birthdate. It was two and a half months a er the onset of the Second World War, so my mother was probably full of anxiety chemicals before my birth. It was also the gloomiest month of the year: dead leaves but no snow, the daylight shrinking but no Christmas yet. It’s the month of death, sex, and regeneration, say the astrologers. ey must have thrown in the last two to sweeten the pill. November’s festivals are the Day of the Dead and Remembrance Day, which is another kind of Day of the Dead. Gloom all round. Given these negative auspices, why did I turn out to be such a cheerful infant? Because I was. ere are witnesses. Or there were.

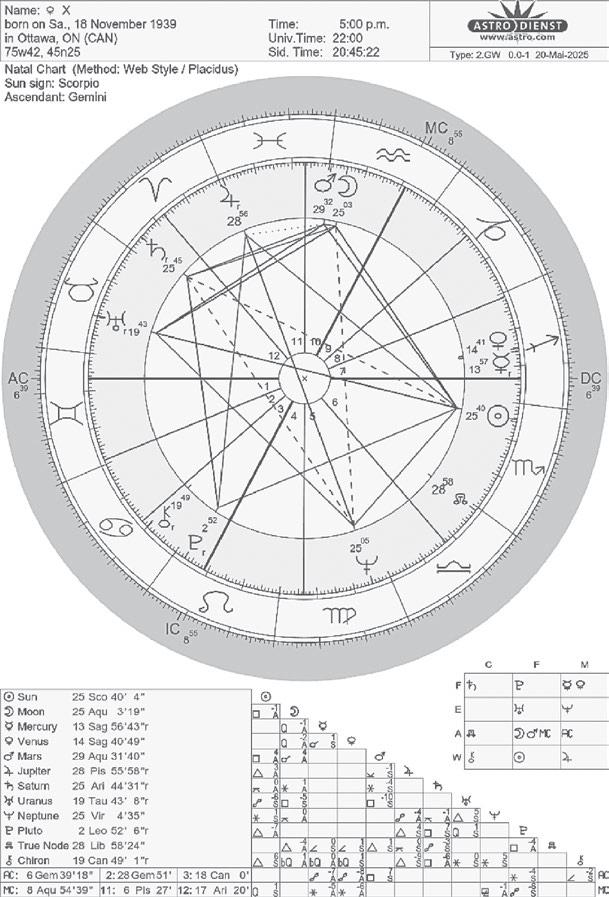

Take one look at my natal chart and you can see my character and destiny spread out before you, as plain as day. (If you don’t like horoscopes, skip this part. And the chart on the next page.)

Take one look at my natal chart and you can see my character and destiny spread out before you, as plain as day. (If you don’t like horoscopes, skip this part. And the chart on the next page.)

Look at that! A Grand Trine (that’s the triangle in the middle), with the Sun, Jupiter (big luck), and Pluto (the Underworld) at the points. Jupiter is at the top of the chart, but in Pisces, so I should have made an e ort to limit the escapism, the daydreaming, and the esoteric interests. (I did not limit them.) Mars and the Moon in the tenth house—that’ll be the poetry publishing as well as some of the artistic ghts. Yes, the Sun is in Scorpio, which could bode ill for others: once thoroughly annoyed, we Scorpios make implacable enemies. e rulers of Scorpio are Ares (Mars), god of war, and Hades (Pluto), god of the dead and the Underworld. Military history, sewer

Look at that! A Grand Trine (that’s the triangle in the middle), with the Sun, Jupiter (big luck), and Pluto (the Underworld) at the points. Jupiter is at the top of the chart, but in Pisces, so I should have made an e ort to limit the escapism, the daydreaming, and the esoteric interests. (I did not limit them.) Mars and the Moon in the tenth house—that’ll be the poetry publishing as well as some of the artistic ghts. Yes, the Sun is in Scorpio, which could bode ill for others: once thoroughly annoyed, we Scorpios make implacable enemies. e rulers of Scorpio are Ares (Mars), god of war, and Hades (Pluto), god of the dead and the Underworld. Military history, sewer

systems, burials, murder mysteries, lingerie, hidden treasure, dirty secrets—all these intrigue Scorpios. We are said to make good detectives, spies, and criminal masterminds. And undertakers.

But breathe easier because Gemini is rising. It’s the sign of the twins: thus, perfect for a writer. e good twin and the bad twin, or the outer twin and the inner twin. e smiling Jekyll twin, going about his/her benevolent and respectable public business, and the Hyde twin, the twin of the shadows, steeped in crime and/or writing books.

e planetary ruler of Gemini is Hermes (Mercury), messenger of the gods, inventor of jokes, guardian and revealer of secrets—hence the word hermetic—patron saint of travellers and thieves, ruler of communications, and conductor of souls to the Underworld. How feathery and airy! How secretive! How prone to mischief! How impervious to horrifying things! How at home in Hades! How duplicitous!

(Being a Scorpio, I’m skeptical about everything, including horoscopes, so take all this with a large handful of salt.)

However, is Gemini really my rising sign? e catch is that my mother couldn’t remember exactly when I was born. In those days, they knocked you out with ether at the crucial moment, so

she was unconscious during my rst breath. My best clue is that the doctors—all men at that time, women curers and doctors having been e ectively dealt with over centuries by being burned at the stake as witches and, later, denied entry to medical schools—thanked my mother for having waited until a er the Grey Cup football seminal. So I calculate that my birth must have taken place shortly a er 5 p.m. My brother had been named a er his two grandfathers, Harold and Leslie. My mother had made a pact with her best friend, Eleanor, to name their rst girl children a er each other. However, my father was a romantic, and—since he adored my mother—wanted me to be named a er her; and so I was, though I was given Eleanor as a middle name.

is meant, however, that there were two Margarets in the family. To avoid confusion, I was given a nickname—Peggy—which is a Scottish diminutive for Margaret. When I was very small, I was sometimes called “Little Carl” because I looked so much like him. I was never called “Margaret,” and didn’t think of it as my name. However, it came in handy later: I had a hidden alter ego, waiting in the shadows for the call to writership. “Peggy” was the Allegro Gemini, but “Margaret” was the Penseroso Scorpio, an altogether more dubious character. into the woods, again

Six months a er being born, I was taken by car along the two-lane highway that runs beside the broad, fast- owing Ottawa River, still used then for driving logs downriver, as it had been since the time of the Napoleonic Wars. (Where did most of the masts for the British Navy ships used in the blockade of France come from? e oncemajestic white pines of the Ottawa Valley.)

We made this journey every spring until I was four and a half. e route went from Ottawa through old towns from the high days of logging: Arnprior, Renfrew, Pembroke, Petawawa—an army base—to Deep River, not yet a centre for atomic research; then to Mattawa, and nally across a bridge and dam that marked the Ontario–Quebec border to the lumber town of Témiscaming. Upriver was the wide

and cold Lake Temiskaming, downriver the o en-hazardous Ottawa River, used for millennia by the Algonquins as a main transport route. is is Canadian Shield country: everything grows on a base of glacier-scoured Precambrian rock. e forest is mixed coniferous/ deciduous, so in the autumn it’s a spectacular blend of red, yellow, and orange, punctuated by dark spruce and pine. Témiscaming was already quite old in 1939, or it seemed so to me later. Some eccentric francophile had donated a French fountain to it, an odd rococo touch in the boreal forest.

Passing through the town, we’d skirt a small lumber mill with a pile of sawdust that was a source of fascination to me. (I wanted to slide down it, but when I nally got the chance, the sawdust was not at all like wooden snow. Instead, it was sticky and itchy.) We’d drive under a huge wooden water pipe dripping with enormous icicles in the colder months. A er that, there were thirty or forty miles along a newly built unpaved road that was narrow, hilly and twisty, carsick-making, and punctuated by blind turns. e road signs were some of the rst French words I ever learned: Petite Vitesse for Low Gear—that was for the steep hills; and Gardez le Droit for Keep to the Right—for the blind turns. You were supposed to honk before turning so that whoever might be coming the other way would know you were there.

Our father was a skilled driver. He didn’t particularly like driving, though he had to do a lot of it in connection with his work. However, driving long distances was easier then: during the war years the roads were quite empty. Gasoline was rationed, and cars weren’t owned by every family—far from it. ose who did have cars had to deal with frequent blowouts: tires were of poor quality, as the good tire material was going to the war e ort. One of my early images of my father was the bottom half of him sticking out from under a jacked-up car.

He had a gas-rationing exemption because forest-based industries were considered crucial to the war e ort. (People have sometimes asked me why he didn’t enlist. He tried to—he wanted to be in the air force—but was told not only that he was in a “critical industry” but also that he was too oldish, and had a heart condition, likely caused by having had rheumatic fever as a child. is heart aw was not immediately threatening, but it eventually caught up with him.)

His specialties as a researcher were the three insects that caused large boreal-forest infestations—spruce budworm, eastern tent caterpillar, and saw y—which could swi ly devastate large swaths of valuable forest. It was a matter of importance to spot infestations, so he travelled all over northern Ontario and northwestern Quebec by car and sometimes by bush plane, collecting insects, observing, and asking questions. Some of his informants were local First Nations people who lived and worked in the forests: they’d be the rst to know if a lot of trees were suddenly dying.

So, being used to backcountry driving, he took the blind turns— as he took the rest of that road, and most roads—at speeds that were possibly not advisable. Our mother su ered from car sickness, but his thinking probably was that if she was going to be sick anyway, why not make it there faster? He was always in a hurry to get places.

At last we’d reach the destination: the northern end of a large, cold, and convoluted lake, scraped out by glaciers over thousands of years. We’d drive through a covered bridge that was built above a dam meant to keep the water level high; the water pressure was used for shooting logs down to the Témiscaming sawmill. Near the bridge were a tiny white church and a few houses. Who lived there? People who serviced the dam and the small-gauge railroad; a couple of backwoods farmers taking advantage of a few patches of arable land among the rocks; perhaps some of the men who worked at logging sites during the winter. Logging then was done with axes, and also with horses, which would drag the felled trees to the lake ice. In the spring, when the ice melted, the trees would be corralled inside circles of logs chained together, called booms, so they could be towed down the lake with little tugboats.

Near the government dock used by the tugboats, Carl would park the car. On my rst trip, my father carried me in a packsack along a trail through the snowy woods. In later years we might be driven over the ice in a sleigh, unless the ice was too rotten.

For the next six months we lived in the small cabin, though the larger house was already under construction. My father was o en away on one of his insect expeditions, and my mother would be alone, with a

toddler and a baby. However, there were visitors from time to time: fellow scientists and friends from Ottawa, and young Uncle Harold, Margaret’s younger brother, who once got lost on the lake, though he was rescued the next day by Carl. It was easy to get lost on that lake.

Was my mother ever lonely or frightened? Yes, a few times, according to family stories. Once was at night, when she heard a loud noise from inside. It turned out to be a porcupine that had got in and upset one of the shelves. Two other occasions alarmed her enough to become stories: a screech owl—these birds sound like ghost babies— and a moment when she and my father were in a canoe, got turned around in a thick fog at dusk, and almost went over the rapids underneath the covered bridge. ey were saved by the barking of a village dog, which let them know where they were.

As a rule, however, Margaret wasn’t afraid of much. Her city friends thought she was mad to pass half of each year in the bush with no electricity, no running water, and no telephone. She said she preferred the woods because there was less housework. You just swept the dirt out the door, and no one expected furniture polish. Or hats and gloves.

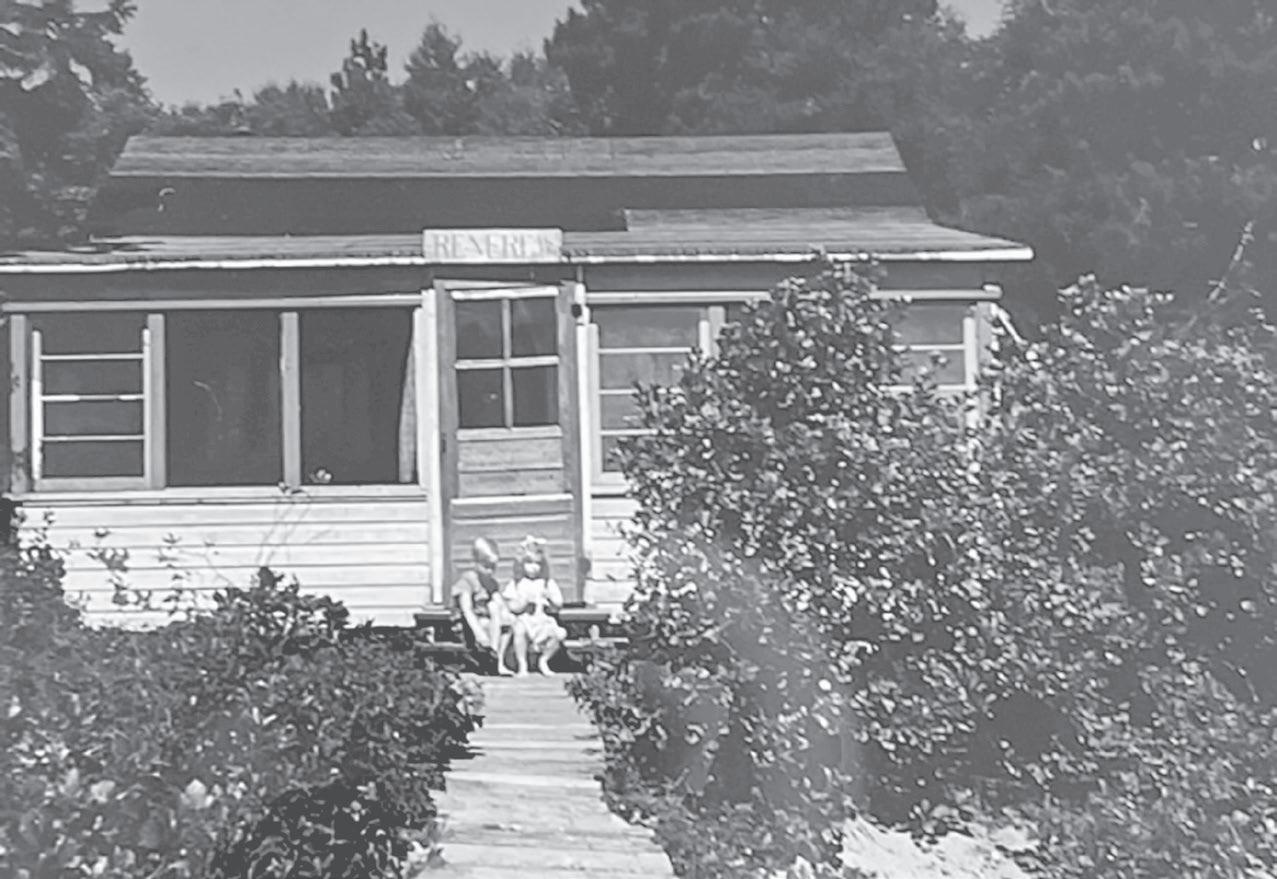

roughout that summer, the larger house was taking shape. Our father built it using only hand tools and some help from Adrien Denis. It was a board-and-batten structure that was quick to put up. It wasn’t insulated, though some of the inside walls were lined with knotty pine boards. e following year, he added a screened porch, essential for life in the woods, because of the mosquitoes and black ies.

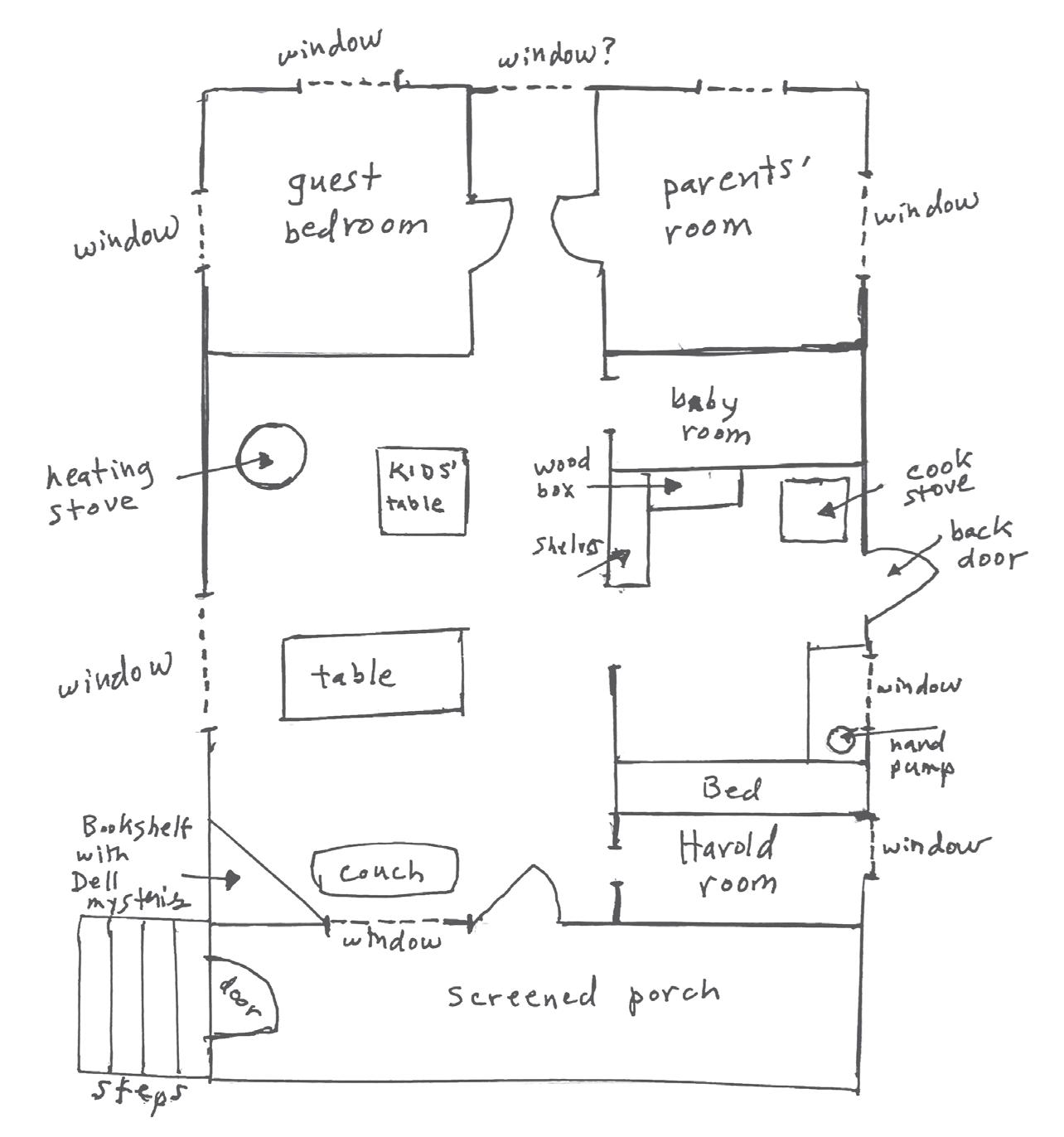

is house disappeared in 1970, having been replaced by a swanky summer home with a road leading to it. But though it has vanished, the house lives on in the Platonic world of forms. I drew this oor plan from memory, and from the clearer memories of my older brother, Harold.

I have only a dim memory of the Ottawa apartment of my rst years—long and dark, smelling of oor wax—but I remember the Red Pine Point house quite clearly. e furniture in it—with the exception of the couch, the mattresses, and the canvas-backed deck chairs—was all made by our father. It wasn’t ne cabinet-making, but it had the supreme advantage of being cheap.

I have my mother’s meticulous account book from that period,

with every expenditure recorded, including boards and nails. Our parents didn’t spend much actual money. Our father, having grown up with even less actual money and a deep education in self-reliance, was of the opinion that you didn’t have to be rich to live a satisfying and comfortable life—satisfying meaning that you were pleased with your work and did it well, comfortable meaning that you were warm enough and dry enough, that you had enough to eat (plus tea), and that you weren’t being devoured by bears. Or black ies and mosquitoes. Or anything else.

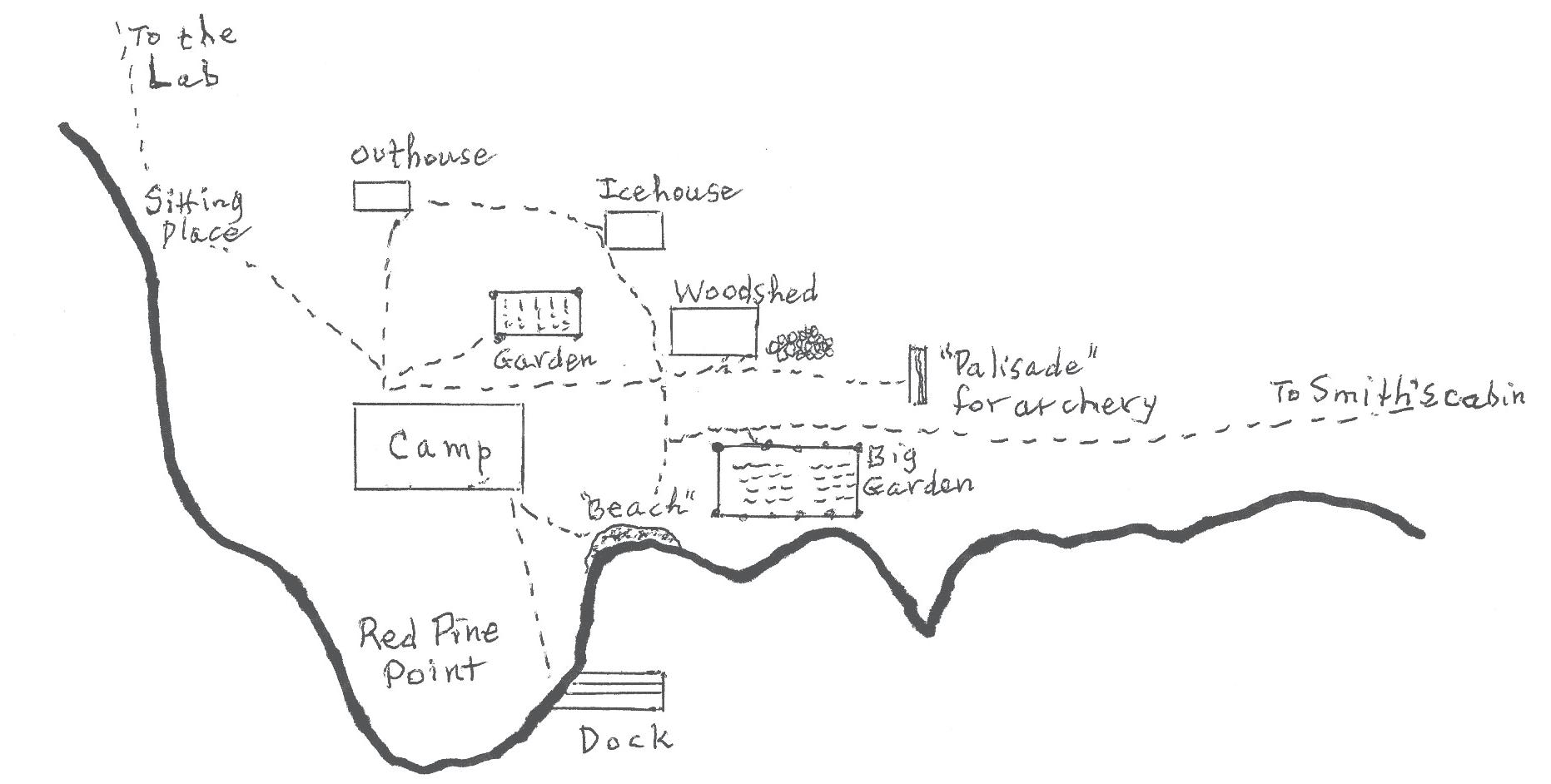

Light was provided by ashlights, candles, and kerosene lamps. Heat was from wood stoves. Water came from the lake, or from a hand pump in the kitchen. ere were two stoves in the house, a cookstove in the kitchen for boiling and baking—it had an oven—and a heating stove in the living area. In the morning both stoves would be lit if it was cold, and while our father cooked the breakfast, we kids could wrap ourselves in scratchy wool blankets and huddle near the livingarea stove, waiting for the house to heat up enough so we could get dressed. It was cold a lot of the time—July and August were the only warm months, and even they could be chilly at night—so that is an early memory of mine: being cold. is is a map of the house and outbuildings, drawn by Harold.

“Camp” is the house. A shadowy, mossy pathway led to the outhouse, a thing of mystery by ashlight. ere was also a woodshed, where the wood for the stoves was stacked, once the trees for it had been cut, sawn into lengths, split with an axe, and rested for a year. You had to let the rewood season: green wood was bad for burning. (Our father did all this woodwork in his spare time; similarly, his house-building and furniture construction, and his boat-building. Our rowboat was made by him.)

We had a little ice house, built from the boards of the small cabin— once it had been demolished by “a wrecking bar,” says my brother— where ice cut during the winter was stored in sawdust to keep it from melting, so food could be kept cold during the summer. Once, in the discarded sawdust behind the ice house, I saw two remarkable alienlooking mushrooms—stinkhorns, and they did indeed stink—which I have never seen since. I didn’t make them up: my brother remembers them too.

e structure labelled “Palisade” was a log backstop for archery practice. Arrows, both target and hunting, were made by hand. Our father and mother were excellent shots, and my brother—having skewered a ru ed grouse when he was merely ten—became a teenage virtuoso. (When I came to archery myself, I wasn’t good at it. Why did the arrows always land to the side of where I thought I was aiming them? e culprit was an undiagnosed astigmatism, linked with near-sightedness. Similarly with the .22 ri e. I understood the theory of both weapons, but was de cient in practice. is was discouraging.)

O to the side of the house my father hung a swing. One of my delights was being pushed on it while he whistled. What was he whistling? “ e Shepherd’s Hymn” from Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony, though naturally I didn’t know that. But the rst time I heard it later, I recognized it immediately.

On or near the dock were the canoes, in which we kids had to sit very still even if the rain was pouring down our backs; also the motorboat with a low-horsepower motor in which our father ran back and forth between the house and his lab, and the rowboat in which our mother used to take us on explorations—once, memorably, to a small island where there was a decaying deer, giving o a

metallic smell. A graphic illustration of what dead meant. We had our picnic elsewhere.

Periodically our mother rowed us to the tiny village about half a mile away to get the mail from the log structure by the government dock. A woman named Madame Delorme had a little shop in the front of her house from which she sold eggs and a few staples. She had a missing hand, a source of fascination to me, and when she wrapped up the packages, she would break the string by winding it around the stump of her arm. (What had happened to the hand? I never knew.) She would insist on giving us kids some butterscotch candies. is annoyed my mother—bad for our teeth—but politeness meant she couldn’t refuse them.

To the north of our encampment, the trail that led to the lab and the village began. In the late a ernoon our mother would take us to a large at boulder beside an enigmatic object stuck into the ground. It had red paint and numbers on it. (It was a lot line marker, but who knew what those were?) We would sit on the boulder and wait for the sound of our father’s motorboat.

Yes, here he came—how exciting! Our father never met a young child he wasn’t prepared to indulge, by playing a game, answering questions about the natural world, or teaching a practical skill, such as re-lighting or the proper use of an edged tool. He’d had four younger siblings, so he came by his child-whispering talents through practice. Later, in Toronto, a young neighbour curious about a worm or a beetle would be sent by her mother to “ask Dr. Atwood, because he knows all about that.” Eventually the child said, “Is Dr. Atwood God?”

ottawa winters and a hurtling chunk of ice

Every fall, once it got seriously cold and freeze-up began, we would go back to Ottawa to spend the winters. In Ottawa it snowed a lot. A lot! Wonderful for snow forts and snowball ghts. We had a sled. Did we have a toboggan? Somebody did. I learned to skate on doublerunner skates on the Rideau Canal, which froze very hard in those days.

Early in 1941, I was standing in the doorway of our apartment building on Patterson Avenue with my mother and brother. rough the air came hurtling a chunk of ice. It hit me in the le eye. “You screamed for three days,” my mother would say with either pride (what lung power!) or resentment (what a racket!). e little boy who’d thrown the ice chunk was sent by his mother to apologize. “I’m sorry I hit Peggy in the eye,” he said. “I meant to hit Harold.” It’s useful to know that you’re sometimes receiving rage and anger intended for a di erent target. Ever since, I’ve had bad relationships with white objects ying toward me through the air. Snowballs or baseballs or tennis balls—I have an aversion to all of them. When any unpleasant thing comes ying at me unexpectedly—a bad review, a false rumour, a sudden death—I think, Ah. Another chunk of ice. And also: is hurts, but you can survive it.

Ottawa: the smell of fresh-cut boards from a lumber yard. And the smell of the mud I would scoop up with a spoon. Smells were very important to me, and I had to be discouraged from saying, as we were ushered into homes we were visiting, “What’s that funny smell?” Quite o en it was oor wax. I’m told that my brother and I once made some mud balls, took them to our second- oor apartment, and threw them out the window at an old man. How did we carry out this plan without being observed? e old man complained to the authorities, namely our mother, and we got a spanking. Spankings were rare events, “but I had to do something,” said our mother when recounting this episode.

My brother started school in Ottawa. During the wartime years, boys of his age collected the cardboard tops from milk bottles—there were many di erent dairies, and milk came in glass bottles delivered by milkmen in horse-drawn wagons. e boys would stand their milk bottle tops up against a wall and other boys would roll theirs at the target. If you hit it, it was yours.

We were sometimes taken by our mother to throw empty tin cans at a big cut-out picture of Hitler. It was a way of collecting tin cans needed for the war e ort. Other items collected included rubber, cooking fat, and silver foil. I still have to think twice before discarding silver paper.

In April, up we would go to the woods again. Here we are in a 1943 photograph on a horse-drawn sledge piled with boxes and driven on top of the ice by a couple of “the boys from the village”—my father’s phrase. (In Nova Scotia, “boys” was a compliment.) e ice would have been very thick: climate change was not yet visible, or even considered.