Also by The Coun T ess of C A rn A rvon

Lady Almina and the Real Downton Abbey

Lady Catherine and the Real Downton Abbey

At Home at Highclere

Christmas at Highclere

Seasons at Highclere

The Earl and the Pharaoh

Also by The Coun T ess of C A rn A rvon

Lady Almina and the Real Downton Abbey

Lady Catherine and the Real Downton Abbey

At Home at Highclere

Christmas at Highclere

Seasons at Highclere

The Earl and the Pharaoh

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Century is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London s W 11 7b W

penguin.co.uk

First published 2025 001

Copyright © Lady Carnarvon, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Extract from Four Quartets by T. S. Eliot © Set Copyrights Limited, 2019. Reprinted by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd

Extract from I Went to a Marvellous Party copyright © NC Aventales AG 1938 by permission of Alan Brodie Representation Ltd www.alanbrodie.com

First plate section, pp. 4–5: Downton Abbey photography © Carnival Film & Television Limited. All Rights Reserved

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Set in 13.4/16pt Garamond MT Pro Typeset by Six Red Marbles UK, Thetford, Norfolk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 yh 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library I sbn : 978–1–529–96393–9

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

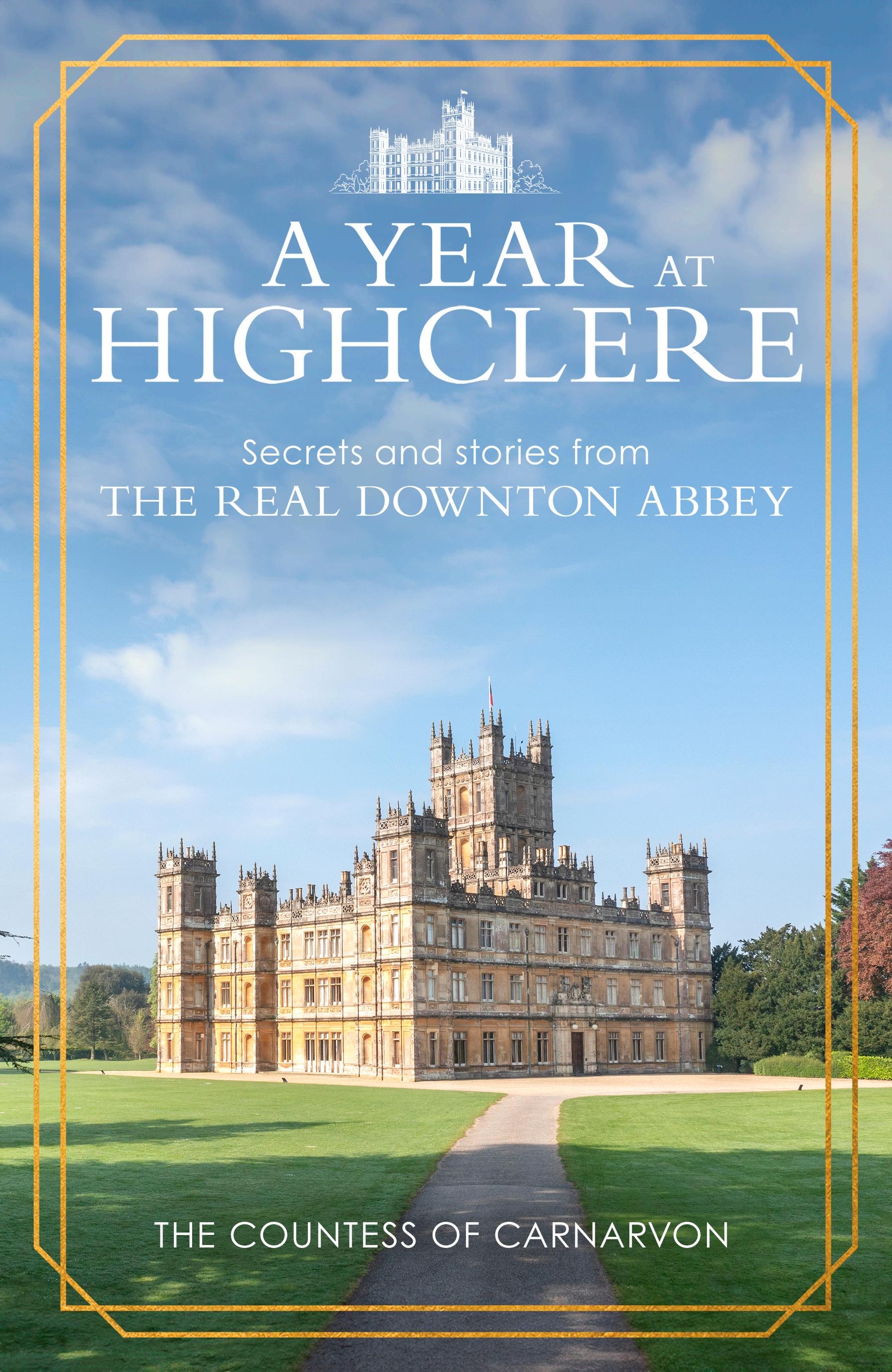

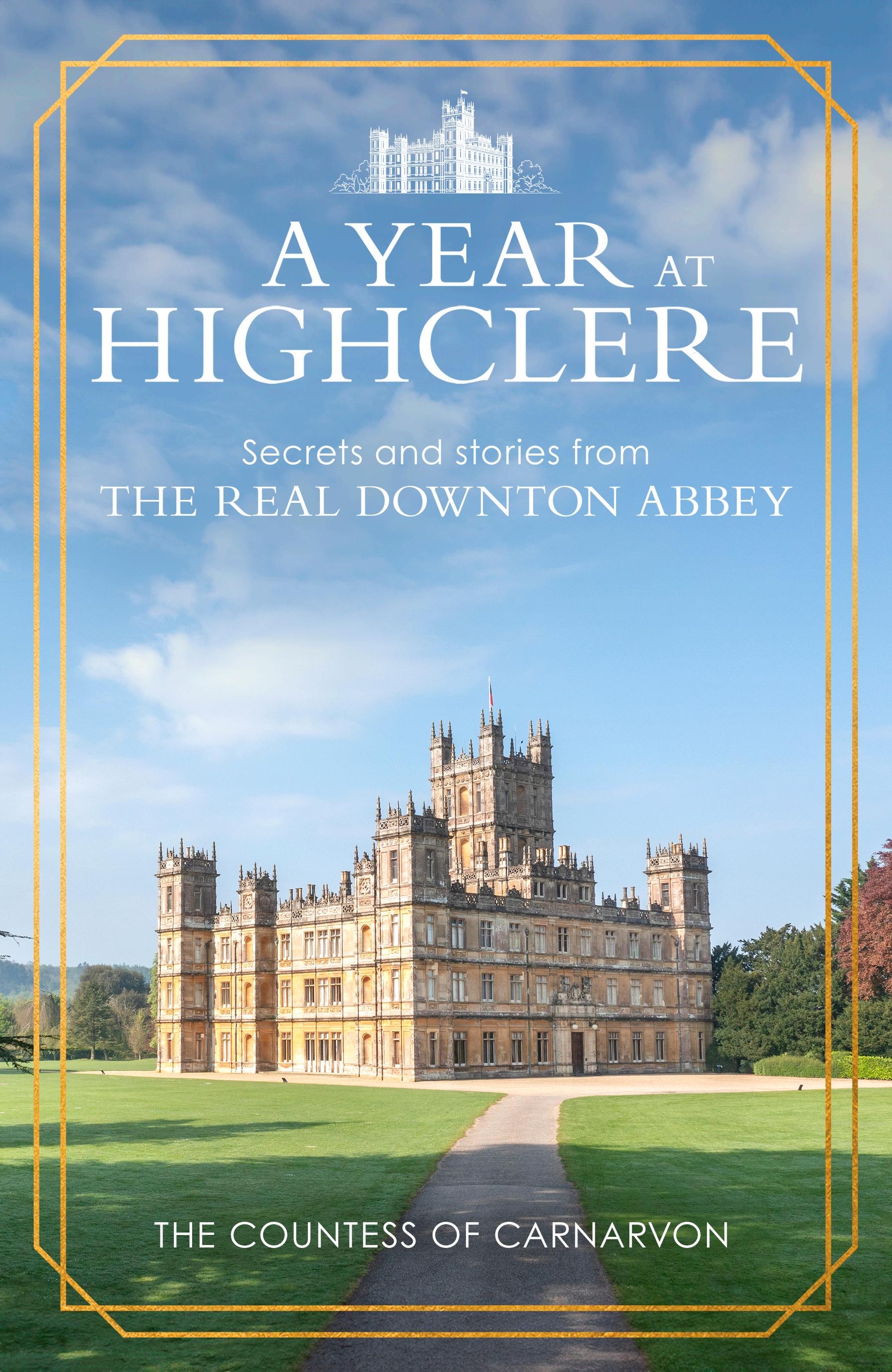

This is a book about what it is like to live and work in a castle today. Built as a home in another time, and for a very different world, Highclere has become one of the most famous castles in the world courtesy of its alter ego Downton Abbey.

Whilst there is obvious visual appeal in the architectural harmony of the Castle and the beauty of its natural surroundings, the real heartbeat of any home comes from the people who live and work there as well as those who have contributed so much to it in the past.

Highclere is about storytelling – the history of the house, the timelines of the ancient trees, the farmland, wildlife, and how they all fit together. The desire to tread lightly on this time- steeped corner of England is intrinsic to this place. From stories about living with a film crew, to the four-legged friends we share our lives with, marvellous parties and ghosts we meet en route, there is never a dull moment.

Life at Highclere, and this book, proceeds in step with the calendar, and as in many communities in England the primary topic of conversation is the weather. There is usually something wrong: it is too cold and wet, too grey, too snowy, which affects horses, gardens, farm and visitors, or else too hot and dry, which affects horses, gardens, farm and visitors; it may be too windy or too still – which could presage hot or cold weather – and there is constant perusal of forecasts and reciting of traditional adages. As the Dowager Lady

Grantham remarked when asked, ‘What do you think makes the English the way we are?’: ‘I don’t know. Opinions differ. Some say our history. But I blame the weather.’

It seems hugely appropriate therefore to draw on the structure of the year to introduce some of the stories about those who live and work here. Highclere is a way of life and, just like the famous TV series and films about Downton Abbey, this book celebrates the eccentric, kind, hard-working people, full of good humour, who enable it to continue.

‘For last year’s words belong to last year’s language And next year’s words await another voice’ – ‘Little Gidding’, Four Quartets, T. S. Eliot

Each January, for six fabulous years, the New Year at Highclere began with a series of recces as the film team returned to plan scenes and once more familiarise themselves with the real Downton Abbey. The TV series was filmed over the first six months of the year and the whole ensemble of cast, crew, white lorries and vans would soon be winding up the front drive. The much-lauded TV series was followed by two feature films with a third awaiting release in 2025. The first film, released in 2019, carried on the Grantham family saga from the point where the TV series ended.

The years 2020 and 2021 were indeed a different era. The second film, emerging in 2022 with fresh trials for the Grantham family, was echoed in real life by an even more challenging new era that affected the entire planet; one of tragedy, swift change and the need to adapt to survive.

Highclere Castle, its estate and landscape, has however travelled through many new eras over several thousand years, and the efforts of the families living here to adapt and change

A

are written in the terrain, on ancient rolls of parchment, in centuries- old letters, modern diaries, and now in digital records as well. In some ways, Downton Abbey itself was a new era for the Castle in that it threw an international spotlight on an estate that had attracted little public notice since the 5th Earl of Carnarvon’s discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun a hundred years before.

The oldest stories, however, begin outside, under the skies, in contact with the land, nature and wildlife.

Standing on the flanks of Beacon Hill at sunset, the current Castle lies a mile away, rooted in the woodlands to the northwest of this chalk hill and just touched by the last long streaks of light as the sun sinks down to rest. Here on the hillside, the spun-gold tendrils of winter sunlight briefly illuminate a mosaic of windswept grasses which, in that moment, seem fitting embellishments to a perfect Arcadian landscape.

The summit of Beacon Hill is defined by the ruined stone walls and foundations of the half-buried, grass-covered Iron Age homes, remnants from a time when people were more connected to and dependent on the natural world. This ancient fortified community marks just one of the many new eras witnessed by the ancient landscape surrounding Highclere.

Iron Age man farmed and lived around Beacon Hill, or Weald Setl as it was called then, for perhaps 800 years, shaping a landscape of pasture and arable land together with managed woodland. They worked their fields and reared their animals: pigs, cattle and sheep, essential for food and survival. Settlements were enclosed for safety and land ownership was important. Weald Setl – which translates as ‘settlement of the chieftain’ – was a communal gathering place, perhaps even a stronghold. Iron Age architecture is characterised by hillforts,

designed to make an impact; they were impressive undertakings, built and achieved through teamwork.

Not much is known of the structure of Iron Age communities. They marked the seasons of the year under the auspices of their religious leaders, druids, beginning with Imbolc, a celebration of light and renewal which took place in February after the darkest days had ended. Beltane on 1 May heralded moving the cattle to summer grazing; Lughnasadh in August was a time to pray for and celebrate the ripening crops, whilst the three days of Samhain marked the return of the dark time of year when the barriers between this world and the spiritual world temporarily opened.

The passing of the days of the year was marked in a different fashion from today. For convenience, mankind now divides up the year into months and weeks, aligning time across the world and across the past on a uniform scale. In reality, of course, the precise beginning and end of any timespan are difficult to distinguish, but the systems of nomenclature and mathematics that we now observe enable these distinctions to be made in ways that would have been surprising to our ancestors.

To Iron Age man, the natural world was fundamental. Then as now, Highclere had good trees – oaks in particular. The word ‘druid’ means ‘oak knower’, and such epithets connected the ancient sages to the earth and nature. Their wisdom was seen as sacred and god-given.

From the vantage point of the tall steep hill on which they lived, the Iron Age farmers would themselves have looked down onto the ancient tumuli of their ancestors, who had settled here several thousand years before. The Neolithic or later Bronze Age burials in the tumuli would still have been respected as sacred places and ancestors would have been left

undisturbed long after the tumuli were built, used or even understood. Still visible on the estate today, they suggest that then, as now, our ancestors found solace in congregation and ritual.

In turn, these Bronze and Iron Age communities would have followed in the steps of even earlier eras, which saw the arrival of the Mesolithic settlers who discovered these newer, warmer lands as the last Ice Age retreated around 10,000 b C , but no traces of these peoples have been found here.

The land around Highclere was first settled and farmed around 4,000 b C . The round Bronze Age barrows date from circa 3,000–2,000 b C and are thought to have been built near groves of oak. It is therefore possible that druids lived here too, and a later Anglo-Saxon document which references the ‘bounds’ of Highclere details a track leading ‘ wiðig grafas ’, towards graves or groves, which suggests a joint inherited linguistic reference.

Prehistoric cultures existed in various parts of the world for over two and a half million years, meaning that 99 per cent of our human experience was gained in the Palaeolithic era (or Stone Age) alone. The Bronze Age tumuli and Weald Setl ( Beacon Hill) of the Highclere Estate represent a history and architecture that is just 5,000 years old. Nevertheless, in terms of being able to touch the past, this hill marks a unique inheritance for us and offers a valuable yardstick to earlier lives in this place.

The golden age of these Iron Age forts, with their ramparts, timber palisades and elaborate fortified entrances, was about 600 b C , and the dismantlement of these communities was the result of the Roman invasion of Britain that began in AD 43– 7 under Emperor Claudius. The Roman General Aulus Plautius arrived in England on the south coast

with four Roman legions, numbering towards 20,000 soldiers, as well as cavalry and auxiliary troops. Well trained and well armed, the Romans steadily advanced northwards, easily overcoming small and fragmentary settlements such as Weald Setl.

Part of our understanding of life in such settlements is due to a Greek traveller and explorer, Pytheas. He sailed around the British Isles in 325 b C and excerpts from his diaries remain, quoted and paraphrased by later Roman authors. He called Iron Age Britons the ‘Pretanoi ’, Greek for painted ones, a linguistic link to ‘Britanni ’. He described Britons as renowned wheat farmers, but a simple people who live in thatched huts, stored their grain in subterranean caches and baked bread. The TV series The Great British Bake Off clearly has ancient antecedents.

Apart from bread wheat and spelt, they also grew ‘eincorn ’, ‘ emmer ’, uncultivated oats and naked and hulled barley, with the latter being the predominant grain. Today, the landscape around Beacon Hill still clearly shows the British ‘square field’ system from this time. Whilst our ancestors found patterns in the sky and the seasons of the year, so we find sustaining patterns in our historic landscapes.

Weald Setl and the modern-day Highclere lie on the border between the Belgae tribes to the south and the Atrebates to the north, and an Atrebates coin found at the foot of Beacon Hill suggests at least some inter-tribe trade or influence.

The Atrebates tribe threw in their lot with the Romans, who gradually developed the town of Calleva Atrebatum, or Silchester, just to the east of Highclere in the centre of their territory. There are also traces of a Roman villa settlement at the foot of Beacon Hill, sheltered from the prevailing southwesterly winds and weather, which may have recycled and reused existing building materials in the area.

For the next 450 years, the land around Highclere was a division of the Roman administration of this new province of Britannia, forming part of its Western Empire until its collapse in AD 500. The Romans built towns and forts linked together by a network of roads, many of which are still in use today, if tarmacked and full of cars rather than soldiers and chariots. The rather prosaically named A34, which passes right by the Highclere Estate, is part of the original Roman route from modern-day Winchester to today’s Manchester.

The same fields were also continuously cultivated. There may have been vines as evidenced in the Roman period at Silchester, but by using the new Roman ploughs, the larger cultivated strips to the east of Highclere could produce better yields and a granary was certainly built there. The Romans introduced domestic fowl, including pheasants, and changed the traditional farm layout of buildings. Previously, animals and humans would have either shared a space or, at best, there would have been one room for animals and one for people. Romanised farms, on the other hand, show a devolution of agricultural functions into outbuildings, which were placed around one, two, or even three yards.

Prosperous estates owned by an urban aristocracy were based on wealth from agriculture, and literary evidence indicates that Britain regularly exported grain to the Continent. This is borne out by the grain-drying furnaces widely found in villa excavations, but perhaps they were also connected to the increased need to dry wet-cut crops as the climate began to cool after around AD 400. Roman agriculture also understood the agricultural principles of reseeding meadows as part of a crop rotation, the three-crop rule, and the value of oats, legumes and roots.

For 200 years, in this country at least, the Roman Empire

enjoyed a stable government with an established judiciary, military security and a vast improvement in communications which opened it to new markets. Yet already by the second half of the third century, the towns were finding an insufficient basis for their economic activities in the rural life of the provinces, and by the fourth century many villas were in decline.

By the sixth century, the chalk and limestone uplands of much of southern England had been drained of their Romano-British peasantry. There is no single reason why this happened, but in part it must have been due to the changing climate and agricultural practices. Higher rainfall and lower temperatures in the latter part of the Roman occupation would have made these upland soils unworkable in autumn, leading to crop failures. There is evidence of a transition to stock-farming and an increased production of wheat in the lower lands, which is better fitted to moist conditions than barley. Combined with state pressure to produce wheat and wool, increasing maladministration, inflation, over-taxation, political insecurity and social disturbance in consequence, economic disintegration was inevitable.

Today, rough stones from the ramparts of the Iron Age fort tumble down the steep northern slope of Beacon Hill, to be hidden in the undergrowth and woodland. Only faint traces of the buildings within the fort, whether domestic or administrative, remain. Grain- storage pits have reverted to earth and the contours of the walls following the line of the terrain are just a muted reminder of the enormous team effort of construction. The signs of Roman occupation are even fainter.

The Anglo-Saxon historian Bede gave a precise date, AD 449, for the beginning of the next new era at Highclere,

which was the arrival of the Anglo- Saxons. They came from three tribes, the Angles, the Saxons and the Jutes, who originated in different parts of Germany and Denmark, so the name Anglo-Saxons was really the simplification of a complex series of migrations into a single term.

Over the first half of the fifth century, the political collapse of the Roman Empire led to the gradual withdrawal of Roman military and civil authority from Britain. In AD 449, there is a record of an appeal from the Britons to Rome for help following the arrival of ever-more armed migrants from the north. However, from as early as the fourth century there are records of Anglo- Saxons being employed and paid by Romans to guard towns and roads in England, so not all were unwelcome.

According to Bede, the West Saxons were originally known as the Gewisse and were based in the Upper Thames Valley, which in turn was part of Wessex. Highclere lies within this region.

Cerdic was the head of a partly British noble family, with blood ties to existing Saxon settlers, who had been entrusted with the defence of Wessex in the last days of British subRoman military power, relying on a mixed population of assimilated settlers and British natives.

Various records confirm the presence of British landowners in Wessex over a hundred years after the beginning of the Saxon conquest, suggesting a steady pattern of assimilation in the area.

This period of history is often referred to as the Dark Ages because of the lack of records to chronicle it. It was also a dark period because of the so-called Justinian plague which, by AD 543, had spread to every corner of the Roman Empire. This was the same bacterium that some 800 years later would be responsible for the Black Death, and research has shown that it too originated in Tian Shan, Central Asia.

As the old way of life collapsed, archaeological records reveal a drastic reduction both in the population and in the standard of living of the British in south-eastern and central England, including obviously Highclere.

Needing a fresh start away from plague-ridden burials and tired land, the centre of life at Highclere moved north, a mile away from the old Roman villas and homes around Beacon Hill. The new site was slightly higher, with good views, and old maps suggest it formed a convenient crossroads.

Wells were made to draw up fresh chalk water, new ovens and farmyards built, and the settlement came to be called High- Clere. By AD 749, the buildings and lands were sufficiently established to be described in an Anglo-Saxon charter. King Cuthred of Wessex, seeking favour from Bishop Hunfrith of Winchester, granted Highclere, the buildings, land and woodland, including what is now called Old Burghclere, to the bishopric, keeping only Kingsclere for himself. The agricultural land at Burghclere was now the focus of farming endeavour and the settlement still had a Roman granary, with a church and village built next to it.

The charter defines the estate at Highclere in just eight lines. The southern boundary was formed from the ‘ hunig weg ’ ( honey way), which then turned down to find the watery ‘wash’ and the ( River) Enbourne, before it described the eastern extent as passing the ‘coferan ’ (tree), and then ‘withig grafa ’ (towards graves), these words implying both the ancient graves and the oak tree groves of their all-knowing forebears. Amazingly, it is still possible to physically ‘walk the bounds’ of this original estate and find much the same heritage bar the northern part, and to observe the archaeological remains from this period.

Over the next 200 years, the population was gradually

A Ye A r At

re-established and a church was built at Highclere next to the farm buildings, with a cemetery to the north. Before long, a walled garden and orchard were built by the bishopric and streams dammed to create five fishponds two miles to the north of the bailiwick or district. By 1208, and the first real administrative records, the bishop had already established a residence at Highclere and a centre for collecting and measuring agricultural harvests.

The first Bishop of Winchester to construct fishponds was Henry de Blois, who was well known for being in the vanguard in terms of estate management and producing high-status food:

In 1315–16 a new fishpond was made . . . and a wooden channel and sluice were constructed . . . in 1350– 1 two channels were dug between the ponds . . . In 1352–3 a weir was built beside the great fishpond . . . A new fishpond was constructed at great expense in 1372–4 . . . a new fishpond was made and enclosed in 1381–2 . . . These ponds were within their own enclosures. [Sourced from the Bishops’ Rolls of Winchester]

Carp was the mainstay of fish farming and records testify that four acres of ponds would return 1,000 carp per year if bred to fourteen or fifteen inches long (about two to two-anda- half pounds in weight). Other fish that would have been farmed were tench, bream, perch, rudd, roach and pike. Presumably one pond would have been a stew pond, not manured or cycled as the other ponds were. This would be used to store live fish and feed them oatmeal in order to improve the taste so that they were ready for eating.

The monks, lay brothers and agricultural workers populating Highclere would have been experts at maintaining the

fish-farm cycle, ensuring there was sufficient water-flow and filtration. In turn, each pond would have been drained and the next one filled, with the surviving fish transferred there. In the meantime, cattle would have puddled and muddled the second pond, which helped to foster the growth of weed on which pond life could flourish. The carp would then eat the pond life.

In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the catch from the Highclere fishponds was reserved exclusively for the use of the bishops and their royal and aristocratic associates, and it was almost always eaten fresh. However, fish could be preserved and Bishop William of Wykeham’s household account roll, which survives from April to September 1393, shows that during this period the episcopal household mainly had to make do with smoked and salted fish.

The Winchester Pipe Rolls dating from 1209–1711 detail income and expenditure across the bishop’s estates and thus provide insight into daily life at Highclere during this period. What is clear is that Highclere was gradually transformed from one of many manors within the bishopric into a significant medieval palace under first Bishop Edington and then Bishop William of Wykeham (1324–1404).

William Edington, Bishop of Winchester (1346– 66), Treasurer of the Realm (1346–56) and Chancellor of England (1356– 63), began the substantial rebuilding works of the administrative buildings at Highclere, as well as improving the agricultural buildings. It was a significant commitment to invest in an area that had previously been devastated by the plague.

However, Highclere really stepped into the hall of fame when it was transformed into a palace by William of Wykeham in about 1360.

Highclere Palace and the surrounding buildings reflected the traditional status and hierarchy of a princely home, and different chambers or rooms in the palace were allocated to the different ranks in the household. For example, the esquires would be allowed to gather together in the Lords’ Chamber in the evening to talk of the chronicles of kings, to play the harp or sing in order to occupy strangers until their departure.

Wykeham’s works at Highclere began with fairly modest repairs and refurbishments using a few thousand tiles in 1367–8 and 1368–9, rising to a crescendo of further expenditure over the following four years.

The hierarchy of the medieval world was based first upon birth and secondly upon service. William of Wykeham was unusual because he achieved the highest rank of royal adviser, architect and Chancellor of England, through service to King Edward III rather than being born of any rank at all. In fact, he was the son of a poor yeoman farmer in Hampshire, near Winchester.

King Edward III was a handsome man possessed with both natural ability and good fortune. Thomas Walsingham described him as ‘a shapely man, of stature neither tall nor short, his countenance was kindly’. The king enjoyed outstanding victories on the battlefield at Crécy and Poitiers in the war with France, was blessed with many children and was also interested in technological advances. For example, he installed a clock on the bell tower at Westminster and initiated the shift from liturgical to mechanical time. William of Wykeham was closely associated with him, granted the rare privilege of private access to the king’s chambers and inner rooms or cabinet.

Most of the entries in the rolls for Highclere are for repairs – of roofs, locks, sills and beams. There are references

to various rooms including a hall and a chapel. Although the estate supplied oak to other building projects, given it was used by the bishop and had a deer park, Highclere itself would probably have been built of stone. The hall would have been on the ground floor but the chapel may have been at first- floor level and have had an apsidal end. By 1240, further buildings were added so that the bishop’s retinue could also be housed at Highclere. There was the chamber for the knights and the squires, for example, along with a wine cellar, dovecote, gatehouse and larder. Over the next decade, a long chamber, a stewards’ chamber, a kitchen and a series of stables were built, along with the inevitable slew of necessary repairs. Some things never change. One courtyard became two courtyards, the outer one for the working areas and an inner one for more refined activities.

These centuries form an important part of Highclere’s history in that they mark over 800 years of uninterrupted ownership. The stability afforded by the bishopric allowed for a period of relative prosperity and the continual development of the estate. In the wider world, it was an era which encompassed great change marked by increasing literacy, beautifully illustrated books, international cooperation in trade and ambitious building projects, both ecclesiastical and secular. With its heroes and saints together with painters such as Leonardo da Vinci, philosophers such as Galileo, explorers such as Columbus, and literature celebrating chivalry and courtesy, this era marked the beginning of the end of the Dark Ages. It is perhaps ironic that the current Highclere Castle celebrates the Middle Ages in its Gothic inspiration and homage to Wessex, from the wyverns carved into stonework of the Castle to the names of the bedrooms.

During the fifteenth and sixteenth century the bishopric’s

interest in Highclere faded and the estate was sequestered by King Edward VI in 1551. It was briefly owned by the Lucy and Kingsmill families before it was acquired in 1677–8 by the current Lord Carnarvon’s direct ancestor, Sir Robert Sawyer. How much of the medieval buildings survived beyond the end of the bishops’ tenure in 1550 is uncertain. The manor house, or Highclere Place House as it was then called, was completely rebuilt in an Elizabethan style in 1616, with a double front constructed of brick and freestone quoins. In 1676, records testify it had a large gatehouse opening into a courtyard, a great stable and a smaller stable, a woodyard and another yard, a long turf-house, barns and a dovecote. At this time, it also had a well-stocked garden of at least an acre in extent and two kitchen gardens, a four-acre orchard and a smaller orchard. The parish church was close by to the west of the house, set in a wholly agricultural landscape of arable fields and meadows, with the village of High Clere nearby. Over the next three centuries the house was much altered. The parish church was rebuilt, mile- long avenues of trees planted, temple and grottos erected and extensive new gardens created for the pleasure of family and guests. Robert Herbert inherited the house from his grandfather in 1706 and improved and extended it in the early eighteenth century, giving new fronts to the south and the east. The next major phase of change took place between 1774 and 1777, when his nephew Henry Herbert, later the 1st Earl of Carnarvon, moved the main entrance of the house from the west to the north. He then built a new nine-bay front with a central pillared entrance. This period was dominated by the influence of ancient Greek and Roman classical design, and so, in the 1820s, Henry’s son employed Thomas Hopper to make further alterations, which saw the house re-faced in stone.

Perhaps the greatest change, however, was in terms of the landscape. Led by a very innovative man of great vision, Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, it was an extraordinarily exciting new era in ‘place making’, which blurred the boundaries between art and nature in a completely contrary fashion to the formal and structured gardens of the previous centuries. It was no surprise therefore that, ever keen to keep up with prevailing trends, in 1770 Henry Herbert duly commissioned Capability Brown to draw up a plan for Highclere Park. His proposals are shown on a document now hanging in the Castle. Whilst many of Brown’s suggestions were implemented, the work was actually carried out by Henry Herbert’s own labourers in order to save some money. He himself wore out his horses riding to and fro whilst the work was being done, so invested was he in the scheme.

Field boundaries were swept away, arable land put down to grass, lakes created and trees and woodlands planted. It is worth noting that Capability Brown had spent some time researching Highclere, seeking to understand the land and its history. He was looking beyond the formal gardens and deliberately working within the bounds of the old medieval deer park.

Later on, the diarist William Cobbett praised the landscape in preference to many other comparable houses: ‘I like this place better than Fonthill, Blenheim, Stowe, or any other gentleman’s grounds that I have seen . . . The oaks are still covered, the beeches in their best dress, the elms yet pretty green, and the beautiful ashes only beginning to turn off. This is, according to my Fancy, the prettiest park that I have ever seen. A great variety of hill and dell. A good deal of water . . .’

The television opening credits for Downton Abbey begin with the parkland and, at the premiere of the first Downton

Abbey film in New York, the spires of the golden sunlit Castle rising above an autumnal glowing parkland was a breathtaking sight, which had the audience cheering and clapping. It gave us all the chance to glimpse the rural idyll that once shaped our relationship with the countryside, the remnants of which still exist if we look carefully.

The version of Highclere that is so known and loved today is the work of the pre-eminent Victorian architect Sir Charles Barry and his client the 3rd Earl of Carnarvon. Both were much travelled in the classical world, particularly Italy, and both brought back a vision inspired by the harmonious principles of Italianate architecture, from the interior’s arches within the central saloon to the external pinnacles and spires reaching for the skies, as well as the Great Tower. The central saloon involved cutting- edge engineering work and its overhead leaded lights ensure natural illumination filters through to those living below. Despite the dramatic changes to the look of the house, it was however essentially a remodelling rather than a rebuilding, removing the Georgian stone facings and extending the footprint and the height.

Sadly, both Barry and the 3rd Earl died before the works were finalised and it was the 4th Earl who completed the interiors of the Castle, including perhaps one of the most glorious rooms, the library. The proportions of the room, its detailing and the collection of 6,500 books, is an enduring legacy, especially when so many great libraries have been dispersed.

At Highclere, the classical is mixed with a grand, essentially British medieval style. In addition, many of the bedrooms were named for the old Anglo- Saxon kingdoms – Wessex, Mercia, Northumberland and Kent. Apart from its influence on Victorian architecture, the ideals of medieval chivalry also inspired the literature of Alfred, Lord Tennyson and Sir

Walter Scott, spinning stories around a golden age of civilisation which projected a romantic morality and fascination with the tales of King Arthur. The 4th Earl of Carnarvon was himself very much a historian and antiquarian, giving lectures on Anglo-Saxon times, and could well be described as a Christian medievalist.

For all the historical associations, its place within a wider community and its longevity within the landscape, fundamentally modern-day Highclere Castle was built as a home – not only for a family but also for the many staff and agricultural workers who lived both within its walls and in the nearby cottages and surrounding villages. It may have been built with all modern aids available to ease life in 1842 yet in today’s terms it is anachronistic – a family home with 250 to 300 rooms and extensive areas for a staff who no longer exist.

Thanks to increasing industrialisation, life in Highclere changed dramatically between 1842 and 1914 as it did everywhere in England. No one date marks the beginning of this new era, but steam ships speeded up global trade, railways began to stretch across countries and continents (as well as counties) and travel became possible for wider swathes of the population. By the beginning of the twentieth century, motor cars were in their infancy, telephones allowed speech through space, photographs miraculously captured images, machines heavier than air could fly and electricity was replacing gas lamps and candles.

If there is one reason why Highclere made it through the swift upheavals of the last century, it was the good fortune of the 5th Earl in choosing a wife with a fortune and the vision to match it. Almina Carnarvon was the beloved daughter of Alfred de Rothschild and he stepped in to provide a dowry of £500,000, some £60 million in today’s terms. He supported

his son-in-law and daughter in various endeavours as well as leaving them another legacy on his death.

Thanks to his generosity, both of them were able to embrace and enjoy the new technologies. Lord Carnarvon was one of the earliest enthusiasts of the motor car as well as a keen photographer. Almina replumbed the Castle and, in 1895, introduced electricity. Entrepreneurs and inventors such as Charles Rolls and the earliest aviators, from Charles Voisin to John Moore-Brabazon, stayed at the Castle, whilst Geoffrey de Havilland made his first flight from a flat field on the southern boundary of the estate in September 1910. Meanwhile, Lord Carnarvon had found his true passion: Egyptology. From 1906 until his death in 1923, both the Pharaohs of an antique land and the modern world of Egypt were to become an integral part of his life as he travelled to Egypt by rail and steamship for several months every year.

Highclere Castle was designed to accommodate family, guests and staff on a grand scale, which it did with tremendous flair and style during this period. Sixty indoors staff looked after the family and its guests, with gatherings ranging from weekend house parties for the grandest in the land to celebrations for 500 local children or staff parties. Always busy, all the rooms were in use, with most of the requisite food supplied by the estate. The vegetable gardens, orchards and greenhouses provided supplies for the Castle kitchens, whilst the tenants on the farm grew grains and kept cows for milking, cattle, sheep, chickens and pigs. Some 250 families lived around the Castle and were part of its various enterprises. This rural community supported and surrounded Highclere, from the foresters to keepers and farmers. Equally, they were supported by Lord and Lady Carnarvon. Even during the years of the First World War, Lord Carnarvon continued to pay salaries to the

longstanding estate families whose sons and husbands had gone to fight. He also bought tea and cheese in huge quantities to help sustain the dependants.

As the casualties mounted and the British Army grew in size, the numbers working at Highclere correspondingly declined. At the same time, more women left to work in a number of different industries to replace the menfolk. With financial support from her father, Almina transformed Highclere into a hospital during the war years. Patients were welcomed into the best bedrooms with good food, beer and kind nurses whose byword was cleanliness, but who were also there to talk with them, help them write letters or venture outside to sit under a tree. Ever practical, Almina had installed an operating theatre in Arundel bedroom and the surgeons arrived by train each Monday, whilst Saturday was visiting day. Several hundred letters record the grateful thanks sent by the patients after they were transferred elsewhere to convalesce following their hospital treatment, usually to houses by the sea where the clean air was believed to be beneficial to healing. The handwriting gave clues about each man’s state of mind, wibbly-wobbly if their hand was injured, sometimes in pencil, sometimes written on headed paper from their next port of call, full of courage and of hope but also sometimes of fear. Fear for the repercussions of their injuries but also the realisation that once they had passed their medical boards they would have to return to the trenches and the theatre of war once again.

The word ‘war’ had been scribbled shakily across the Highclere visitors book in August 1914 when the country still hoped it would be over by Christmas. Instead, for five long years, Lady Carnarvon never ceased welcoming casualties to her home. If the scale of the wartime suffering was beyond

understanding, on an individual level nevertheless Highclere offered compassion and healing.

Eventually, it was over and the Armistice was signed at 11 a.m. on the eleventh day of the eleventh month in 1918. Quite literally, the guns fell silent. Everyone hoped it was a new era of peace.

The year 1918 radically reshaped the map of Central and Eastern Europe. New nationalistic forces took the place of the previous three powerful empires – Germany, Russia and Austria- Hungary – and the early interwar years began with economic uncertainty, taxation and inflation. Lord Carnarvon sold off the Bretby Estate in the Midlands and struggled to practise economy to balance the books. Into this world came the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922, a golden glimpse into a distant realm. The ancient Egyptian civilisation far outpaced its European equivalents in terms of sophistication and knowledge. Whilst Highclere’s Bronze Age inhabitants scraped a living in mud huts, the Egyptians built the pyramids and created incredible works of art.

The 5th Earl died too young aged just fifty-six and once more Almina came to the rescue. Her father’s collections went on sale at Christie’s in 1925, considered one of the great sales of the century. A number of paintings from Highclere were also included and the finest Egyptian antiquities were sold to the Metropolitan Museum of New York in order to defray death duties.

If Highclere Castle entered the 1920s and 1930s with optimism, the lack of a crystal ball to predict the next few decades can only have been a positive. The 6th Earl (my husband Geordie’s grandfather) did survive two World Wars and continued to live in the Castle throughout his life. However, he often said to Geordie, ‘I am the last of the

Mohicans, darling boy.’ It was an amusing remark, but at heart reflected the prevailing mood in the quietly decaying great houses of England. They cost too much to staff and maintain, and perhaps as many as 1,200 of them vanished in the period after the Second World War to the mid-1970s.

The 6th Earl (1898–1987) may have believed economy was the rule of the day at Highclere but this was not financial constraint as we might understand it. His staff in the early years after he inherited consisted of a butler, a valet, a first footman, a second footman, a hall-room boy, an usher, a head chauffeur, a second chauffeur, a chef, a first kitchen maid, a second kitchen maid, a scullery maid, a still -room maid, a housekeeper, five housemaids, an electrician, a night watchman, a head groom and two under grooms.

Writing in 1972, the 6th Earl’s butler Robert Taylor commented:

I’ve served Lord Carnarvon for over 35 years and during that time I have seen so many changes but since World War II we are struggling to continue. I am one of the last of the old guard and none of us are getting any younger. Highclere remains as it has done for hundreds of years but now it’s an island and the waters are lapping at the doorway. At 60 I feel young and strong and at 75 his Lordship is robust but our individual faults must become more obvious as each day passes though no doubt, we both make our concessions the one to the other.

As with the Great War of 1914– 18, the Second World War fundamentally changed English society. In the 1940s, Churchill himself noted that it was only in hindsight that he recognised the underlying currents of socialism sweeping through