EX LIBRIS

VINTAGE CLASSICS

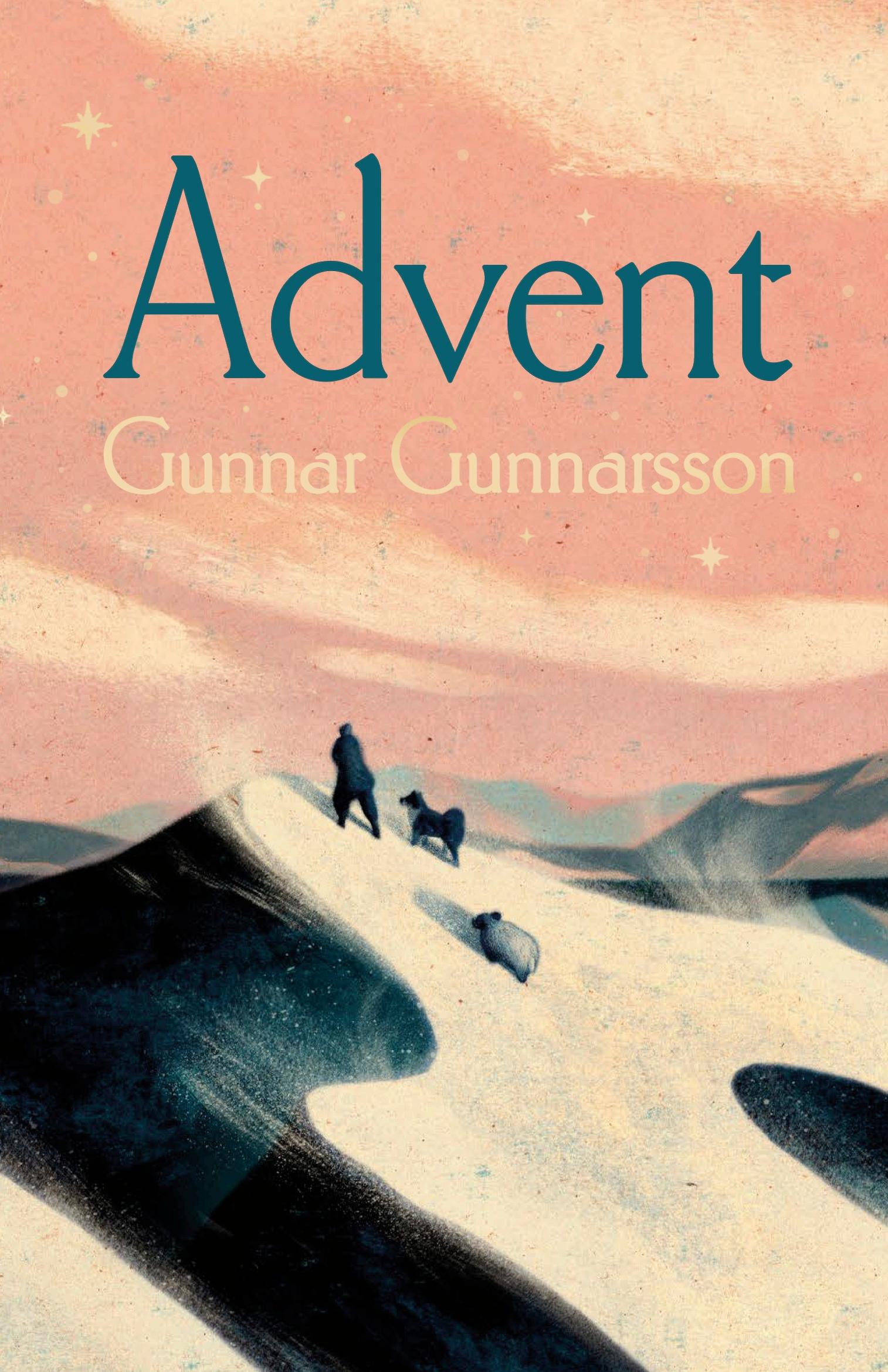

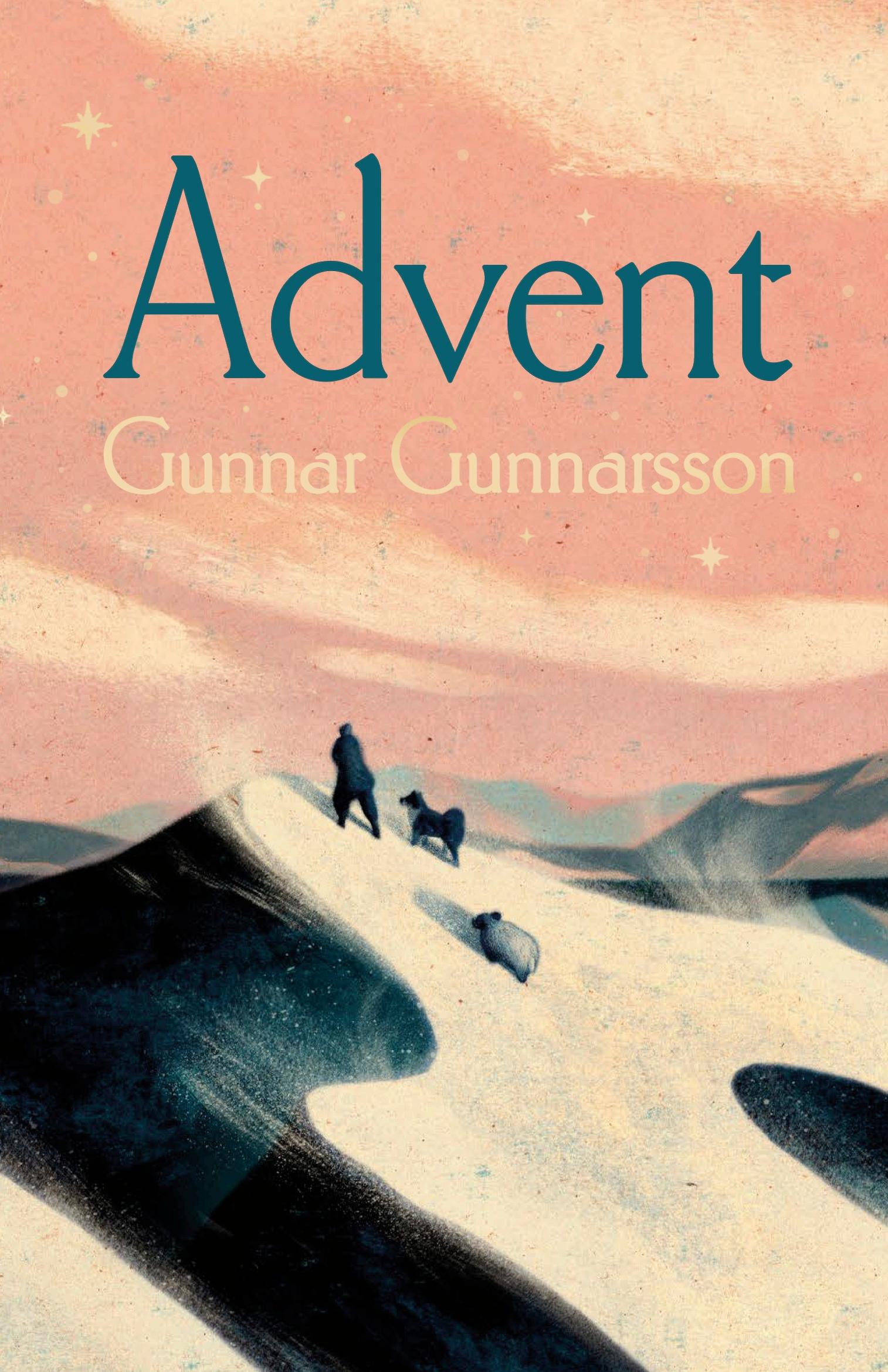

gunnar gunnarsson

ADVENT

translated from the danish by Philip Roughton

with an afterword by Jón

Kalman Stefánsson

Vintage Classics is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies

Vintage, Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London sw 11 7 bw

penguin.co.uk/vintage-classics global.penguinrandomhouse.com

This edition published in Vintage Classics in 2025

First published in Denmark by Gyldendalske Boghandel Nordisk Forlag in 1936

Copyright © Gunnar Gunnarsson 1936

Translation copyright © Philip Roughton 2025

Afterword copyright © Jón Kalman Stefánsson 2006

Afterword translation copyright © Philip Roughton 2025

The moral right of the copyright holders has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset in 14.2/17pt Bembo Book MT Pro by Six Red Marbles UK, Thetford, Norfolk Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d0 2 yh 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 9781529963076

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

As a feast day draws near, everyone prepares for it in their own way. Many different approaches are taken, and Benedikt had his own too. It consisted of his leaving home at the start of Yule, preferably on Advent Sunday itself, weather permitting, amply equipped with provisions – a few changes of socks and several pairs of newly stitched leather shoes in his rucksack, along with a Primus stove, a can of paraffin and a small bottle of methylated spirits – and heading into the mountains, where at this time of the year only winter’s hardy raptors, foxes and a few stray sheep roamed. It was precisely those wandering sheep that he was after, sheep that had been overlooked during the three regular roundups of the autumn. They certainly couldn’t be allowed to freeze or starve to death in those high places simply because no one bothered or dared to seek them out and bring them home. They too were living creatures. And he bore a certain responsibility for them. His goal was quite

simple: to find them and bring them home safe and sound before the great feast day sanctified the earth and brought peace and contentment to the hearts of those who have done all that they are able to do.

On this Advent expedition of his, Benedikt was always alone. Truly alone? He had no human companions, in any case. He was, however, accompanied by his dog, and most often, his leader sheep. His dog at the time of this story was named Leó – a veritable pope, Benedikt called him. Due to his toughness, the leader sheep, a wether, was called Eitill.*

For a number of years, these three had been inseparable when it came to such treks and had gradually got to know each other, inside and out, with the in-depth familiarity that is perhaps only obtainable between completely unrelated species of animals, such that no shadow of one’s own self, one’s own blood, own wishes or desires confuses or obscures things. There was, incidentally, usually a fourth member of the group, the good horse Faxi, who unfortunately was

* The Icelandic word eitill means ‘knot’ (as in a knot in wood) or ‘node’. Something that is eitilharður is extremely hard in texture.

too slender- legged and heavy- bodied to trudge through early winter’s deep drifts of soft snow, and what’s more, was hardly fit to withstand so many strenuous days on the meagre rations with which the others made do. It was with sadness and regret that Benedikt and Leó parted from him, even if it was only for a week. Eitill took this twist like everything else: more stoically.

There that threesome went now, this winter day: in front was Leó, with the tip of his tongue sticking contentedly out of the right corner of his mouth despite the cold. Behind him was Eitill, even- tempered as always, and finally Benedikt, lugging his skis. Down here in the farmland, the snow was still too light and loose to carry a skier; he had no choice but to trudge through it, and of course ended up stubbing his toes on tussocks and rocks – oof. It was a fairly heavy slog, but it could have been worse. Leó had lots to look into, as dogs usually do, and was in high spirits. At times he couldn’t contain himself and simply had to let it out, bounding away and kicking up a cloud of snow behind him towards Benedikt, barking at him, jumping up at him and clamouring for praise and petting.

Yes, you’re a veritable pope, Benedikt would remark. That was his term of endearment for his comrade; higher praise couldn’t come from his mouth.

For the moment, they were making their way through the settlement towards Botn, the farm lying nearest the mountains. They had the whole day ahead of them and took it easy, following the path from farm to farm, stopping and greeting people and dogs, but a cup of coffee, no thank you, not today – we’d like to get there in good time. Instead, they had some milk – all three. Time and again, Benedikt was questioned about his outlook on the weather. People didn’t mean to be nosy or come across as doomsayers, they simply asked – as was their right, of course. And someone might add afterwards: Yes, what I wanted to say was, Leó must be the kind of dog who’s good at finding the way, even in darkness and snow? It was said almost jokingly, eyes fixed on the ground to avoid alluding to the sky’s somewhat-threatening clouds, even if only with a glance. And someone else might interject spiritedly: Find the way? That he can certainly do, the mongrel.

All three of us can, Benedikt replied uncon-

cernedly, before finishing his bowl of milk. Thanks for the drink.

Nothing against you and Eitill, but I would rely mainly on Leó, said the farmer, before popping out of the door and fetching a treat for Leó to munch on.

Benedikt made no comment about Leó being a veritable pope, but let the dog know with a nod that he was free to take his time eating the food offered; he could wait that long. Meanwhile, Eitill got a capful of fragrant hay from the farmer’s homefield. Then the three of them set off again.

Benedikt hadn’t gone to church that day. No, that he hadn’t done; there wasn’t time for it. In order to reach Botn at a decent hour and get some rest before the following day’s early departure and long march, he’d had to make the best use of the day, starting early that morning. It was mainly out of consideration for Eitill that he set a gentle pace this first day. Not that Eitill couldn’t cope with going faster or didn’t live up to his name. But Benedikt had to be careful not to overexert the wether from the start. That’s why he couldn’t very well make a detour to the church. Every Advent Sunday, it was this amble of his through the settlement towards the mountains that was his

churchgoing. What’s more, before he left home, he’d sat on his bed in the family room and read the day’s scripture passage, Matthew 21, concerning Jesus’s entry into Jerusalem. But the ringing of the bells, the singing of hymns in the small turfcovered church and the old priest’s wise and sedate exposition of the Gospel, he’d had to imagine. And he had no trouble doing so.

Here he was now, walking in snow, white on all sides as far as the eye could see, a greyish-white winter sky, even the ice on the lake was frosted or lightly covered with snow, only the rims of the low craters sticking up here and there drew larger and smaller black rings like a portentous pattern in that snowy waste. But a portent of what? Could it be discovered? Perhaps these crater mouths said: Let everything freeze, stone and water solidify, let the air freeze and sprinkle down as white flakes and lie like a bridal veil, like a shroud over the ground, let the breath freeze in your mouth and the hope in your heart and the blood to death in your veins – deep down, the fire still lives. Perhaps that is what they said. And what, then, did that mean? Perhaps they said something else, too. In any case, apart from those black rings, everything was white,