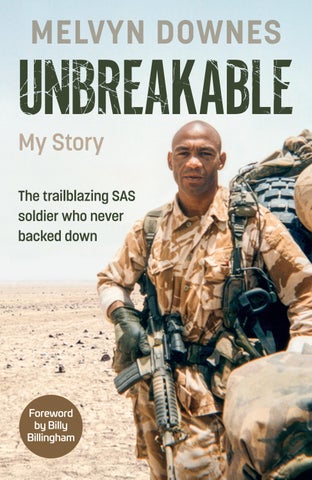

The trailblazing SAS soldier who never backed down

Foreword by Billy Billingham

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Ebury Spotlight is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW

penguin.co.uk global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published by Ebury Spotlight in 2025 1

Copyright © Melvyn Downes 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with

Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset by seagull.net

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Hardback ISBN 9781529961096

Trade Paperback ISBN 9781529969375

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

To my wife, Zoe, and kids, Amy and Sam

Foreword

by Billy Billingham ix

Prologue: Nothing Else Matters 1

Chapter One: Never Back Down 13

Chapter Two: Do the Dog 35

Chapter Three: Why Are You Here, Soldier Boy? 53

Chapter Four: We’ll See Who’s Boss 83

Chapter Five: Desert Rats 111

Chapter Six: The Mighty Seven 133

Chapter Seven: Life Is Not a Rehearsal 157

Chapter Eight: Salad Cream 181

Chapter Nine: Beat the Clock 199

Chapter Ten: What Have We Done? 225

Chapter Eleven: The Most Dangerous Place in the World 245

Chapter Twelve: They’ll Really Sort You Out 265

Epilogue: This Is All We’ve Got 295

Acknowledgements 307

You think you know a bloke.

You fight alongside each other for years. You sit across from each other in the mess. You have nights out drinking. You appear on the same bloody television show. Then you read their book and realise that in lots of ways you didn’t really know them at all. It’s funny that one of the biggest talkers I know, a man who loves to chat, would be silent about so much that has shaped his life. He never really told us about the racist abuse he suffered when he was a kid at school, or the way that he’s taken constant inspiration from the example set by his parents. We were there for him when he was going through his darkest emotional struggles, but I don’t think he ever really let on how far he almost fell. Still, I’ve been lucky enough to watch him at work and play for over 30 years, so there’s a lot in the book that didn’t come as a surprise.

Like a lot of the blokes in the regiment, Mel’s had to graft for anything good that’s come in his life. He’s also had as many dances with death as anyone else I know. I reckon what’s got him through it is his mindset. Mel’s relentlessly positive and totally

resilient. He’s able to make the best of any situation because he’s learned that whether you’re a special forces operator or an accountant, at some point life’s going to throw a whole load of nonsense in your face. And then, just when you think you’re safe, it’ll do it all over again.

You can’t stop that happening. What you are in control of is how you react. If you’re like Mel, you’ll take a moment, flash the world a smile, then roll your sleeves up and get to work.

The other thing that I think shines through in this book is Mel’s unshakeable integrity. That’s one of the reasons he thrived from the first moment he stepped through the doors at Hereford. He’s a stand-up bloke, always the first to offer to take responsibility, the first to put his hand up when he knows he’s messed up, the first to put himself forward when one of his mates needs help.

The nature of our work means that only a very tiny number of people will ever hear the truth about what the SAS have done and continue to do in the service of our country. We knew about that secrecy when we signed up, so none of us could, or would ever want to, complain about the discretion we all have to show. So there’s a lot Mel has had to keep under his hat. He’ll take a lot of those things to his grave.

Still, Mel’s book is as good as anything out there at taking you right to the heart of battle. His long career before joining the SAS and the years he spent protecting journalists in some of the world’s most dangerous places mean there’s no shortage of action to choose from. (I can’t believe the lunatic volunteered to go to Baghdad with little more to protect him than a pistol

and body armour that barely covered his T-shirt! Even harder to believe: he lived to tell the tale.) Reading it transported me to my own experiences in combat. It’s there in his recall of tiny details. The noise bullets make as they ping off the outside of an APC. The smell that rises from men struggling to conquer their fear. The sheer weirdness of fighting in the unnatural green glow shone by our night-vision goggles. The sickening feeling that comes when one of your mates is hit.

He’s honest about the ways in which these things have impacted him. Like so many who’ve spent so much time in uniform, he’s still fighting a lot of ghosts from his past. I really respect his willingness to open up and talk with brutal honesty about the challenges these have presented to his mental health. I’m sure this will help others, from every walk of life, to do the same. Knowing Mel, he’d be delighted with that. It probably sounds like a bit of a cliché but I don’t really care. Mel is one of the good guys. A modest bloke with a hell of a lot to boast about. He’s written an amazing book that I hope he’s proud of. He should be.

All I want to do is get out. I hate doing this. I don’t like being so high up, I don’t like being burdened by so much gear.

I’m in the hold of a shuddering, rumbling transport plane, thousands of feet above solid ground. The journey is conducted in semi-darkness. Even on night missions the lights are kept low, to ensure that we’re not shocked by the transition into the dark skies outside.

With everyone and all their weapons and kit in, what had seemed like a gaping space begins to feel claustrophobic. Some of us are even sitting on our packs. Others are on the floor, their knees up by their chins.

All around us is the reek of engine fuel. But as we get closer to our destination, I can smell something else: adrenaline rising from other men’s bodies; steadily increasing nervous energy. There is barely an inch to move in. When I feel too cramped, I try to stretch, lifting my legs up into the empty air above us –there is nowhere else for them to go. More than anything, I am desperate for fresh air.

The hours before a mission are always strange. Occasionally we will get updates through our radios. Otherwise, we are left to our own devices. Some of us put headphones on – when I need to get myself in the right frame of mind, I’ll blast out ‘Paint It Black’ by the Rolling Stones or ‘Live Forever’ by Oasis. We often talk about football, or other subjects that have no connection to what we are about to do. We know there is nothing we can do except wait, so we just chat about life, take the piss out of each other. It’s not until the last few minutes, when we know we will soon get the signal to move, that this changes.

But today none of this is possible. It’s so loud inside that we must shout to make ourselves heard, even when talking to the man sitting directly beside us. So we all retreat inside our own heads.

I look around and see blokes with their faces daubed in camouflage paint. We’re all swaddled in layers of clothing as a protection from the cold that increases as we climb higher and higher into the air. But to begin with, we’re all uncomfortably hot: sweat is already pooling beneath my fatigues and the body armour that encases me front and back.

For a few moments my mind drifts away from what we’re about to do. I have been a soldier all my adult life. First with the Staffordshire Regiment, then with the SAS. There are times when I think about all of the things I have done and seen, all the places I have been to, all the times I have been in combat, and feel a kind of vertigo: did all of this really happen?

Those experiences can blur into one. But at other moments, like now, fragments from these events return to me with almost painful clarity. The way the face of a man who I had just killed

in close combat changed instantly. His skin had been pink from heat and exertion, then all the colour simply disappeared. He was ghost-pale. Though everything had happened incredibly quickly, it did not feel that way to me. Time slowed down to a sludgy crawl. My senses became almost ferally acute. I felt assailed by the stench of blood, sweat, gun oil and fear.

The time when, once, behind enemy lines, we had been caught in the open. A shell erupted into the ground nearby – the spotting round. While the rest of our patrol sped off, my own vehicle refused to start. We sat there, our Land Rover’s engine coughing weakly, almost like a kitten, knowing all the time that someone was watching us. As I and everyone else in our vehicle looked round to see where the shell had come from, that man was quietly feeding instructions to the soldier charged with aiming and firing the weapon. Next time, I knew, they wouldn’t miss.

A jolt, probably turbulence, snaps me back into the present. As I woozily try to recover my focus, we’re given the sign that I’ve been dreading since I clambered onto the plane: we’ve reached an altitude where we need to clamp our oxygen masks onto our faces. It’s not as bad as breathing under water but my claustrophobia intensifies. There’s something unnerving, almost inhuman, about hearing your breath coming in loud rasps. It reminds me of going to the dentist when I was a kid.

We have all switched on now. I can feel something beginning to sweep through my body. It is not fear, exactly. I have never entered a terrified, fight-or-flight state. If I did, then I’d be really worried, because it would mean that I was panicking. What I experience instead is a state of heightened focus.

Everyone is in their own headspace now. It’s good, this nervous energy. You need it. I have always thought that this time must be similar to what footballers experience as they wait in the tunnel for a match to start. Hearing the roar of the crowd. Clearing their minds of everything except what they need for the next hour and a half. Everything for them, as it is for us, is about right here and right now. Nothing else matters.

A dim red light comes on above the plane’s rear door. Two minutes to go. We stand and the loadmaster ushers us towards the rear of the plane. I look around at my mates’ faces. None of us like this. We know we’re not going to be jumping into clear skies. Tonight is a dusk jump. We’re all anxious about the murk outside. Night jumps are the worst. There’s so much kit, you’re going so fast, that the risks of disaster increase exponentially. Everyone here is aware of the stories of the lads who didn’t land safely. There have been deaths and injuries in the past. There will be deaths and injuries in the future. It’s another of those uncomfortable ideas we’ve all had to get used to.

The danger of a collision is exacerbated at night, when the only way of spotting one of your comrades is the red glow stick on the front of one of their ankles, and the green one on the rear. It’s like watching fireflies, or tracer. There are times jumping at night when there are so many darting streaks of colour in the sky that I struggle to believe that we are not drifting above a firing range.

The doors open. There is a powerful rush of fresh air. We waddle up towards the lip of the doorframe, struggling with the

cumbersome weight of the ammunition, radios, food, water and all the other operational equipment we’re carrying.

As I approach the door, I’m suddenly enveloped by the shocking cold of the atmosphere outside. The green light comes on. This is it. Away we go.

Except, there is nothing dramatic about our exit from the plane. The idea is that you don’t leap, you ease yourself out, as if you’re sitting down in an armchair. Somebody who jumps like a kid splashing into a swimming pool will be spun round by the wind. But if you get it right, it’s like whooshing down a big slide.

As soon as I let go, I feel the slipstream grabbing hold of my body. The sheer force of it pushes me sideways before I begin my descent. My canopy won’t unfurl in its entirety for another couple of hundred feet. For the moment I’m still dropping, dropping, dropping, dropping. I shout, ‘One thousand. ’ My guts have leaped into the roof of my mouth. None of my organs seem to be able to adjust to the pace at which I am travelling. ‘Two thousand.’ My heart, my liver, my lungs; they all appear to be in a different place from the rest of my body. ‘Three thousand.’

I ready myself for the colossal thump of the canopy once it’s filled with air, then the jolt forward as my entire momentum is altered. For a second, I will be lifted upwards, like a puppet being jerked on a string, then the drift down can begin.

I’m always relieved once that moment has been negotiated safely. From that point on, I should be able to control my descent. When you get it right, even though you are still

hurtling through the sky at an unbelievable pace, it seems as if you’re floating slowly and elegantly down.

When you’re so high, surrounded by the frigid ozone, your comrades below descending in elegant S-shapes, you feel like a spaceman. You have the astronaut’s sense of giddy wonder at the perspective you have been granted on the world beneath you. It’s only when other men shoot past you, or the wind turns and you look at your GPS, that you can comprehend the lethal speed at which you’re travelling.

You think to yourself: This is special.

At least, that’s what should happen. Because this evening something has gone wrong. My exit from the plane wasn’t clean. Instead of easing myself gracefully into clear air, I realise I must have wobbled into the sky. Now I can see the cords of my parachute are tangled. The wind and the weight of my gear send me tumbling round and round.

The constant, nauseous twisting dislodges my goggles. Suddenly my eyes feel assaulted by a fierce, unrelenting rush of wind. Worse, I can feel my oxygen mask slipping until it is half off. Fuck, this is not good. There is nothing good about this. As the flow into my lungs slackens I start to feel dizzy. I cannot afford to pass out, and at this height I won’t have long before my body and mind begin to shut down. My cold fingers scrabble around the edge of my mask, trying and eventually managing to make it cover my mouth.

But I am still plummeting through the atmosphere, if I can’t properly open the chute soon it’ll be too late. Adrenaline is sluicing through my body. My mind is frantic.

I need to work out what I can do to save myself. I don’t do these jumps that often, I don’t have the stored-up reserves of experiences that mean I can contemplate what is happening to me calmly. But I know I cannot spiral into a blind panic. You’ve got to try to find that still point, otherwise it’s so easy to make things worse.

Should I try to get myself out of this twist, or would it be better to just release my main chute and open the reserve? Even if I manage to resolve the tangle it might not be enough to save the situation, because there are always new problems you’ve not anticipated. But if I discard my first parachute and pull the reserve handle, that means another freefall, and no guarantee I’ll have any more luck. OK, I think, taking deep draughts of oxygen to try to steady my racing heart. I can fix this.

I start kicking to loosen the twisted cords. Each attempt sends me spinning back in the opposite direction, which in turn threatens to tangle me further. Eventually I manage to work myself free and instantly the canopy opens and my descent loses the jerky, uncertain quality that had been so alarming. I take a moment to compose myself, then attempt to locate the other lads in my stick.

I begin to start fiddling with my GPS, but it is twenty degrees below zero and without mittens my fingers feel numb, swollen and clumsy; it’s almost impossible to make the device function. It’s at just this moment that I pass through a large cloud. Instantly my world shrinks to the dense fog that envelops me. My eyes, unprotected by goggles, are scratched at by sleet and hail. To top it all my radio ear-piece has tumbled out.

Everything that could have gone wrong so far, has gone wrong. I catch myself wondering: What the fuck is going to happen next?

When I emerge into clear sky I feel a moment’s relief. This is followed by more anxiety. With only a couple of thousand feet to go, I’ve still no idea where the rest of the stick is. All I do know is that I’m miles away from the drop zone. I’d expected to see it – a tidy green space suitable for landing – somewhere beneath; instead, there is a small village. The loadmasters must have dropped us off at the wrong location.

A little distance away is a small field. It’s not where I’m supposed to be landing, but it looks safe and free from obstacles. I turn my parachute towards it. As I drift closer, I notice that it’s bisected by a muddy brown track. This in itself is not a problem. What is a threat is the row of telegraph poles that stand either side of the path. Shit, I think, if I hit them, then that’s it for me.

I tug hard on the cords, hooking my parachute around so that I’m facing in the opposite direction. But though I’ve managed to avoid crashing into the telegraph poles, the wind is now behind me. You’re not supposed to land like that, because you want to be slowing down as you approach the ground. The gust at my back is forcing me to accelerate over the last few feet. The ground seems to be hurtling up towards me. I crash into it and my world becomes a jumbled mess. I turn over and over and see the grey of sky, then the green of the grass. The grey of sky, then the green of the grass. The grey of sky, then the green of the grass.

Eventually my momentum slows and I come to a crumpled stop. Breathless, my body a symphony of pain, I lie there for

a few seconds, gingerly moving each of my limbs to see if any bones have been crushed in the fall. My head is spinning, everything pulses with agony, but it seems I am OK.

I need to find my mates, because we have work to do. Right, I tell myself, a mixture of excitement and relief – almost elation – singing in my blood, let’s get started. ¤

Here’s the thing about the people that end up in the SAS. Most of them are like me: normal, jeans-and-T-shirt-wearing kinds of blokes from council estates. We’re not supermen, we’re not James Bonds or ninjas, we don’t have magic powers. We’re not special, there’s no mystery about us and there’s no room for bullshitters, or people with airs and graces: we’re just resilient, dedicated soldiers.

But I have led a life that has exposed me to an extraordinary range of experiences and I’m excited to tell you my story. I’m proud of the journey that has taken me from being a terrified boy chased home from school by racist bullies to a soldier in first the army, and then the SAS, where I was one of the first British-born Black men to join the regiment. I’ve served everywhere from Northern Ireland to the Middle East, as well as a whole host of places I can’t tell you about, protecting the country I love so much. In the years since I retired from the forces, I’ve travelled to some of the world’s most dangerous places to help protect charity workers and journalists as they do their incredible work in the aftermath of natural disasters, or in brutal conflict zones.

There have been mad times, bad times, sad times and crazy times. I’ve had emotional, physical and psychological trauma; financial struggles and health problems; I’ve been through grief and divorce; I’ve lost close mates and close family members; and I’ve experienced bullying and racial harassment. It’s been a lot, though maybe not much more than most people encounter. What I believe, however, is that you can get through it all if you’ve got the right willpower, the right mindset.

I wasn’t born fearless, or strong, or confident. Those things are the result of hard work and a willingness to learn from my mistakes, as well as a constant desire to push myself out of my comfort zone. The SAS’s founder, David Stirling, laid down five principles that he wanted new recruits to his unit to live by: humility, integrity, humour, a classlessness and the unrelenting pursuit of excellence. I didn’t set out deliberately to embody them, but I realise now that they have informed everything I’ve ever done. There is no witchcraft in any of this. You don’t need to be an elite soldier to follow Stirling’s ideas. They might involve graft and dedication (nothing good ever comes easy), but they are simple and clear, and I believe can help you get the best out of yourselves, to live without limits, and to build the resilience you need to keep going when life throws one of its curveballs (which it will).

This book won’t shy away from the darkness and challenges we all encounter. At the same time, I also want it to carry a positive message, because that’s the sort of person I am. No matter how tough things get, I’m always convinced that I will get out

the other side. Some things will hit you harder than others. You might need to take one step back to take two steps forward. But as long as you’re still breathing, you’re still in the game. More than that, I believe that we’re on this planet to live life and enjoy it. I don’t take things for granted, and never have done. And so I thrive on everything.

I hope I can help you do the same.

Everyone loved Sam Downes. Especially women. Sammy, as people outside our family knew him, took such pride in the way he presented himself to the world. His manners were perfect. He’d always be suited and booted, even if he was just out for a couple of pints. Shoes polished, tie and white shirt immaculate. The smell of Old Spice. He wasn’t bothered that the other men in the pubs he went to had black around their eyes from the pits, or hadn’t shaved. At Christmas he’d put on a dinner jacket, the only one at his working men’s club who did. He just wanted to show that he cared.

Sam, my dad, was part of the Windrush generation. He was 18 when he left Clarendon in Jamaica. Like so many of the people that made that journey, he was a patriot – the sort that would have a picture of the Queen on their wall – who thought he was coming to the motherland. He expected to be welcomed with open arms. But, of course, it wasn’t like that. He arrived in a country where people were still putting up ‘No blacks, no Irish, no dogs’ signs. Later, he’d tell me about seeing them as he wandered, with Irish friends, trying to find a boarding house that would give them a room.

There was a part of him that was always on guard. Whenever he was in a pub, even one he’d been going to for years, he’d

stand with his back to the wall. I think sometimes: What must he have been through before I was born that taught him to be so wary? How many mistakes did he make before he learned?

And yet he also believed that you should be free to go wherever you wanted. He’d walk into anywhere. Talk to anyone. That’s the sort of person he was. Nothing was out of bounds for him. And the thing about Sammy was, he seemed to change other people. He didn’t argue with them or try to make them feel bad about stuff they said or thought. He just showed them that he was someone who deserved respect.

Some of that was because of the way he carried himself and treated others. And some of it was because he stood up for himself. He wasn’t a bully and he never went out looking for a fight, but he had a reputation for always standing his ground. If he saw another person having a tough time he’d want to help. He couldn’t bear the idea of being somebody who just walked by. I remember the first time I witnessed this side of him. I was outside a pub near our home, nursing a bottle of pop and a packet of crisps while Dad drank inside. A man started on a woman; I didn’t know why. Then, suddenly, my dad had emerged from the pub and was right by them, shouting, ‘Hey, pack it in!’ in his broad West Indian accent.

In response, the man started abusing him. The same vicious, racist stuff Dad must have heard so many times before. But he wasn’t prepared for how this small, balding but dapper figure tore into him. One punch after another, then a headbutt, going at the man like a little hurricane. I was terrified; there’s nothing that can prepare a kid for a sight like that. And then, a few

seconds later, Dad was back outside the pub, talking to me, as if he’d just gone to get a pack of fags from the shop. The only signs of anything unusual were the deep-red blood stains on his shirt.

We never talked about why he was like that. But, looking back, it’s obvious: he needed to be. If he hadn’t, he wouldn’t have survived for a minute.

I don’t know how he ended up in a small place like Stoke. There wasn’t any sort of West Indian community to speak of in this poor, white working-class town in the North Midlands. But there was work. Dad was a manual labourer. Pits, then building sites, then the pottery factories we called potbanks: graft that left his body scarred but strong. He wasn’t a big man, but he was hard as nails, with hands as tough as a rhino’s hide. Right through his life he’d walk for miles to work, whatever the weather, in his overalls. Even later, when he was at a factory, people would see him running up and down flights of stairs on his breaks.

My mum, June, was 16 when she met Sammy, in 1957. When she was 17, her own mum kicked her out. Dad had the wrong colour skin – my grandmother was one of the few human beings whose mind he couldn’t change.

The young couple didn’t have much money, so they started their lives together in bedsits, living alongside other recent immigrants in parts of Stoke called Shelton and Cobridge. My brother Stephen was born first, in 1959. Then, five years later, I came along.

I spent the first three and a half years of my life surrounded by people who had come to Britain from all over the world.

I remember men in turbans, women in brightly coloured dresses, and the smells that came from different cuisines being prepared at the same time. It always surprises people how much I can recall from those times. It surprises me, to be honest. It comes to me a bit like a dream. There was Jean, a big plump woman in a green velvet dress who used to look after me. Jean was the landlady of the big house we lived in. I have this memory of her holding me on a balcony. Another image is me standing up in my pushchair, looking over the railings onto the canal below, accompanied by two young Indian men who used to take me for walks.

When I was almost four we moved from our bedsit to a flat of our own in a council estate called Bentilee, which when it was built ten years before had been the largest bit of social housing in Europe. It was only four miles away, and yet it was like landing on another planet. The first place we lived was a two-bedroom flat on Kendal Grove, which somehow managed to feel roomy after the bedsit.

The people of Bentilee were overwhelmingly white. Most of them had jobs in the mines or local factories. Back then, Stoke wasn’t just a potbank renowned for its pottery, it also had several pits. Everybody in the city seemed to work with their hands. And everyone seemed to work hard.

The streets were full of smog, from the factories that belched fumes day and night. There was no relief indoors, either, because everyone constantly smoked cigarettes: in offices, houses, working men’s clubs and buses. There were nights when the fog in my dad’s club was so thick that I couldn’t find him. That’s what

we smelled right through my childhood: fags, smoke from the factories and oatcakes, the local speciality.

Although it was the sixties, there were parts of Stoke that might as well have been Victorian. You’d still see rag-and-bone men, blokes in heavy leather jackets and flat caps delivering coal from a cart, and housewives in headscarves. But what I almost never saw was people like me. There were 4,500 homes on the estate. Only one of them was occupied by another Black family.

Overnight we were confronted by something that was new to my brother and me, but probably painfully familiar to my parents. Some of our new neighbours didn’t want us living near them. They appeared to hate us and didn’t care if we knew.

Men and women spat at us, and called us niggers. They hurled abuse from the tops of buses, or as they cycled past us, or as they crossed our paths on the pavement. We never responded. We’d just keep walking in the same direction. The only sign my mum or dad would give that something unusual was happening would be the way they squeezed my hand more tightly. Sometimes I’d ask questions: ‘Why are they saying that, Dad?’ or ‘Why don’t you do anything?’ Dad would just say, ‘Ignore them, ignore them.’ He got more abuse than any of us, but I think my mum – who had filth like ‘nigger lover’ screamed at her – suffered most. It left me angry, hurt and perplexed. It wasn’t clear to me why we were being singled out in this way.

On my first day at school, I turned up wearing a beautiful cardigan my mum had knitted. It was yellow with two brown bunnies. I’ll never forget it, nor how proud I was when I put it