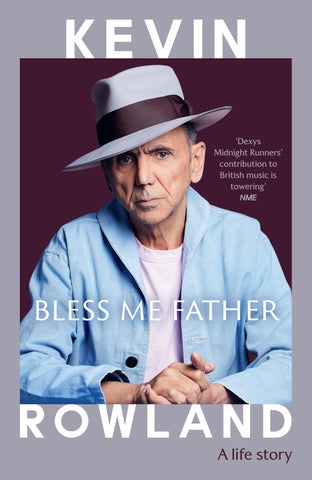

KEVIN

‘Dexys Midnight Runners’ contribution to British music is towering’ NME

bless me father

‘Dexys Midnight Runners’ contribution to British music is towering’ NME

bless me father

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Ebury Spotlight is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW penguin.co.uk global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published by Ebury Spotlight in 2025 1

Copyright © Kevin Rowland 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

The publisher and author have made every effort to credit the copyright owners of any material that appears within, and will correct any omissions in subsequent editions if notified.

This book is a work of non-fiction based on the life, experiences and recollections of the author. In some cases, names of people have been changed solely to protect the privacy of others.

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset by seagulls.net

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781529958720

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

I’ve changed a few names, other than that, this is it – warts and all, mainly my own.

What was different about me? 2

I’ve stolen from the sweet shop 4

The church was sacrosanct 5

A singing priest 18

‘He’ll always be a thief’ 24

I learned Cockney very quickly 30

Usually guilty of something or other 53

Money for fags 61

No sex education 67

My school life was a mess anyway 76

All stick, and no carrot 96

Rolo of ’Arra 103

Trying a few different jobs 112 ‘Virginia Plain’ 122

‘You lads shouldn’t be here’ 133

A favourite means of mind alteration 141 I was in turmoil 151

Infidelity and trust 158

I wanted to be part of a scene 166

An average punk band 179

Us against the world 188

We wanted to be our own thing 201

At someone else’s party 213

The stars were aligned 226

‘Why didn’t you just do it?’ 233 ‘I’m coming with you!’ 242 ‘You’re treading new ground’ 251 We were happening! 256 I’m successful – I should be happy 267 Any figures sounded like abstract fortunes 277

‘Endearing Young Charms’ 286 All I had left was the music 295 Swimming against the tide 303

What the fuck happened? 312 I much preferred ecstasy 318 ‘You’re a McDonnell’ 326 I was living only for cocaine 334

Big man with the cufflinks 348 In touch with my femininity 355 Unable to live in the world 358

‘The worst mess I’ve ever seen’ 361 ‘Pat, Pat, Pat’ 365 I could sense the suffering 367 I didn’t like their vibe 372 Once a man, twice a child 374 I’m going somewhere better 380 State of grace 385

Acknowledgements 389

Image credits 390

Song credits 391

I stood in wonder across the road from the cinema and watched the teenagers queue up to see the new Elvis film. The boys wore tight trousers, pointed shoes and leather jackets. Their hair was greased into quiffs, or James Dean-style.

The girls wore fantastic colourful, sometimes polka-dot dresses, over thick hoop petticoats. They had beehive, heavily lacquered hairstyles and sexy, dark eye make-up.

In those days, to me, Wolverhampton was a place of magic. This was 1961. I was born in ’53.

Elvis sang: You’ve gotta follow that dream wherever that dream may lead.

I bet they’re having a great time in there, smoking cigarettes, looking good, kissing their beautiful girlfriends, eating sweets, watching Elvis singing, kissing, dancing, and fighting. Everybody cheered when Elvis fought. And these teenagers looked great – rebellious, relaxed and cool.

Elvis sang about the man who can sing, regardless of what he has or hasn’t got, being king of the world. That sentiment, and the way Elvis sang it, made perfect sense to me.

But there was a different reality for me at home.

One evening, when I was eight, we sat in the living room after dinner (tea, as we called it). Dad was sitting in his armchair when my older sister, Sarah, started a conversation.

‘What do you think I’ll be when I grow up, Dad?’

‘You’ll be a teacher,’ Dad said to Sarah.

She looked happy.

‘What about me, Dad?’ asked my oldest brother, Pat.

‘You’ll be a businessman,’ he said.

Pat seemed content with that answer.

I don’t remember what was said to Grainne (my younger sister) or Joe (my older brother), or if they even asked the question. But I know that I did.

‘What do you think I’ll be, Dad?’

He paused for a few moments, became suddenly very serious, and said, ‘You’ll be married with a kid when you’re 17.’

I didn’t say anything. I pretended not to know what he meant – but I did know (my brother Pat had already told me how babies are made). In those days, the early sixties, when a girl got pregnant, the boy married her. Plus, Dad had a younger brother, Paddy, who had got married at 16 under those circumstances.

Was I bad, weak? What was different about me compared to the others? There must be something wrong with me. I felt he could see right into me.

Dad’s outlook was the one that dominated our household. He was very strict and he perceived stuff like Elvis lyrics to be over-sentimental. To be clear, Dad did think music and singing were things to be enjoyed, but only in their place – like on birthdays, or later when we had a car and would go on a holiday. Music was not to be confused with work. That was serious. From the youngest age, my dad told me that my interests in music and clothes were wrong.

This book isn’t some rock’n’roll story of how a kid with a disapproving father rebels, eventually finds his own tribe and becomes a pop singer. This is a story of someone who took what his dad said very seriously, believed it and internalised it, so that it became his reality.

Now I’m ten years old. I’m standing in Sister Pauline’s office. She’s the head nun at my junior school, and I’m crying, begging her not to tell my mother that I’ve been caught stealing for the second time in a few weeks. The first occasion was from other kids’ coat pockets in the cloakroom, and now I’ve stolen from the sweet shop nearest the school. I had popped in before school and a boy in another class had seen me steal a penny chew.

As we stood in line in the freezing-cold playground, waiting to go into our classrooms, Rubuski quickly put his hand up and proudly shouted, ‘Please, sir. Kevin Rowland stole a penny chew from the shop!’

My heart sank as he said it. Blood rushed to my head.

‘Oh no!’ My world came crashing down on me.

Now I’m in trouble.

‘Rowland? We’ll deal with you later,’ said the form teacher.

The teacher informed the head nun, and I was summoned to see her. I’d previously promised her that I wouldn’t steal any more, but I couldn’t seem to not do it.

And now they’re going to tell my mum. It will break her heart. She thinks I’m good. I’m supposed to be going to boarding college to be a priest next year.

I begged her. ‘Please, Sister, don’t tell my mum!’

An hour earlier, the head nun had told me that I would be let off with a caning. But now she’s called me back again to tell me that she’s changed her mind – she’s going to tell my mum, after all.

‘Please, please, Sister. Please, Sister, don’t tell my mum.’

The church was sacrosanct

I had started stealing at the age of seven.

I pleaded with my mum, on that lovely warm summer evening, to let me go out with ‘the boys’ – my older brothers Pat, aged 13, and Joe, 11, plus all of their mates – Pat’s gang. Mum stood on the front doorstep, while Pat and the boys were congregating outside the front gate. More boys seemed to arrive every minute, until there were about ten of them, mostly aged between 11 and 13.

Mum had curly black hair, soft tanned skin and kind, blue eyes. I had been pestering and begging her, but to no avail. Pat was joining in. ‘Come on, Mum. Let him come with us.’ She kept saying, ‘No, he’s too young!’

I went back inside the house and looked in the mirror. I saw that I looked scruffy. I washed my face, brushed my hair, came back out and tried again: ‘Mum, please let me go!’ This time, she smiled and said, ‘OK.’

I don’t know if Mum was touched because she’d noticed I had smartened myself up, or if she just had a change of heart, but I was allowed to go.

As we walked down the hill of the old terraced houses on Park Street South, I felt a wave of freedom come over me. I was out with ‘the boys’!

All the local kids respected and looked up to my brothers. They brought excitement wherever they went. And Pat Rowland was the leader. He was like Elvis – good-looking, charming, bright-eyed, with the warmest smile. I didn’t just look up to him. I worshipped him!

We passed through what everyone called ‘the old buildings’ – derelict houses due for demolition. Joe, older brother number two, ran into a house that was already half falling down. A minute later, he emerged

barefoot, wearing a battered straw hat, a check shirt and scruffy trousers rolled up to his calves. He had a tobacco pipe in his mouth. I watched in awe as one of the boys lit it for him.

‘Call me Huck!’ Joe shouted to everyone (after Huckleberry Finn). Pat, and some of the other boys, were now lighting up cigarettes. Wow! This was exciting!

We were walking with purpose now, and Pat was giving instructions on which shops should be targeted and the strategy we should employ. Before long, we stopped outside a small corner shop on the Dudley Road.

‘Mahoney and Mac, you two keep ’em talking,’ Pat said. ‘The rest of ya, grab anything. It don’t matter what it is, just fucking grab it! OK?’

‘OK, Pat,’ we all said.

We piled in. The boys split up, moving into different alcoves and corners of the shop. I noticed a big display of Pal, a popular dog food at the time, so I grabbed a small tin and just about managed to squeeze it into the front pocket of my summer shorts, though the shape of the tin was visible behind the fabric. Almost immediately, I heard a voice from behind the counter.

‘Cum ’ere, yow!’

I walked towards her. She was a fat middle-aged lady. Her thin husband stood dutifully beside her.

‘Empty out yur pockits!’

I took out the tin.

‘Pur’ it on tha countah!’ I did.

‘Where do yow live?’

‘127 Park Street South.’ My mother had just taught me to memorise my address, in case I got lost.

‘Roight, I’ll be round to see yower mutha tonoight.’

We trailed out. Pat’s mates all started chastising me.

‘You stoopid bastard! Watcha give her the right address for?’

It hadn’t even occurred to me to give a false one.

‘And watcha nick dog meat for?’ Pat said. ‘We haven’t even got a fuckin’ dog!’

‘You said, grab anything!’

Mercifully, the shopkeeper didn’t visit our house.

Empty-handed, we made for the boys’ den. It was way into the derelict buildings, and very difficult for any outsiders to find. It was packed with the proceeds of previous endeavours. The boys didn’t just have packets of crisps; they had cardboard boxes full of crisps. They didn’t just have bottles of sweet fizzy pop; they had crates of it!

I soon came to understand that Joe was by far the most fearless of the gang. As the rest of us gorged ourselves on crisps and pop, he stood up, looked around at us all, and with an air of authority said, ‘This is kids’ stuff. When I grow up, I’m gonna rob banks!’

Wow. That sounded great! Robbing banks, just like the cowboys in the films.

•

Joe was the type of boy who would do anything. And I mean anything. At the end of the school day, he would often take me home. One night, as we walked through Snow Hill, a busy street in the centre of Wolverhampton, he decided he needed a piss. He saw no need to find anywhere quiet to relieve himself, or to return to the school, which was only a hundred yards away. He didn’t even see the need to stop walking. He just took out his cock and pointed it upwards so that the urine shot high up into the air like a fountain, and pissed as he walked.

A middle-aged lady sneered as she walked past us. ‘You dirty dog!’

‘Ah fuck off, you old cow!’ Joe shouted at her.

On another occasion, he insisted we both stood outside a newsagent’s for what seemed to me like eternity. I didn’t understand what was going on. Then I realised Joe was waiting for the owner to go into the living area at the rear. As soon as she had, he got down on his knees and reached his hand up to the door handle. Ever so quietly and slowly, he opened the door without fully engaging the noisy bell that was attached

to the top of the door. He then crawled across the shop floor over to the counter, reached up and calmly took down a John Wayne cowboy annual he’d been coveting since a previous recce. Just as silently, he crawled back across the floor and out of the shop.

The book would have cost seven shillings and sixpence, a lot of money to us in those days. Joe loved John Wayne and he happily studied the pictures as we walked home.

Older brother number one, Pat, was a kind boy. My dad worked long hours and Mum had lots to do with running a house for five kids, so in the school holidays and weekends, Pat was like a guardian to us.

He loved musical films and took Joe and me to see Carousel , Oklahoma! and Calamity Jane, among others. Pat’s passion for 1940s and 50s musicals was unusual for a boy of his age at that time. Some of his mates would tease him, attempting the dance moves as they mocked, saying, ‘One minute they’re talking to each other, the next minute they’re singing and dancing!’

‘Fuck off!’ Pat said. He liked what he liked and wasn’t easily swayed by others.

He took me to a funfair one time. Mum had given him two shillings, enough for four or five rides between us. He kept paying for me to go on rides but didn’t go on any himself. After a while, I spoke up. ‘Pat, why don’t you go on any?’

With a big smile on his face, he said, ‘I’m just really enjoying watching you going on them.’ He was like that.

Pat and one or two of his mates would occasionally take me into the town centre and send me up to women. I’d tell them, through fake tears, that I’d lost my bus fare home and that I lived in Bridgnorth, a good few miles from Wolverhampton. Pat and his mates kept the money. I didn’t mind. I enjoyed being with them. •

‘Not when I went to school,’ he said. I thought that was hilarious.

• • •

There was a wealthy area close to where we lived called Goldthorn Hill. The houses were big and the streets were wide, tree-lined and well cared for. Joe suggested he and I go up there and ‘get a bike’.

It was a lovely summer’s day as we walked up the hill, past the beautifully manicured gardens, until we spotted two kids’ bikes strewn across the drive of a big expensive-looking house.

‘OK, Kev, let’s go.’ Joe picked up the bigger of the two bikes. ‘Quick! Get on the crossbar!’

As we rode off, Joe said he thought someone from inside the house might have seen us. We sped down the hill like crazy, singing at the top of our voices.

I wah, wah, wah, wah, wonder, why, she ran away, my little runaway

A speeding car overtook us and pulled up directly in our path. We had to stop. Two boys jumped out, then the father. He was a bald posh guy.

‘Right, let’s have the bicycle,’ he said.

We got off it and the man put it into the back of his estate car.

The older of the two boys started angrily shouting at Joe. ‘If you want a bike, you should jolly well ask your father to buy you one!’

Joe shouted back. ‘We’re poor. We’re not like you. Our dad can’t afford bikes like your dad can!’

‘Come on,’ the man said to his boys quietly, ushering them into the car.

I loved Joe’s passionate honesty and sense of justice, but I had never thought of us as poor. I thought poor meant starving. But Joe saw the stealing in Robin Hood terms – taking from the rich.

Dad was putting a lot pressure on Joe to pass his 11-plus, the grammar school entrance exam. It seemed to be the constant theme in the house. Education was Dad’s number-one obsession.

At my age, seven, the word ‘exam’ just sounded funny: ‘egg-zam’. I thought of it in terms of a giant egg that Joe had to get past.

Dad had been shouting at Joe about the importance of passing. Afterwards, Joe left the room. I followed him to the front of the house, where he was standing alone. As I walked through the door, I said jokingly, ‘Joe, haven’t you walked past that giant egg yet?’

But Joe wasn’t laughing – he was upset. His hand was up to his mouth. He was breathing very quickly and frowning. I hadn’t seen anything like that before and I felt bad for having made the joke. Joe didn’t pass the 11-plus.

Our family were strict Catholics and I’d started serving on the altar, assisting the priests in performing Mass, from the unusually young age of seven. I’d begged Mum and the priests to let me get involved. Soon I was with Joe and the other altar boys for a weekly training session, and within a few weeks, I was wearing all the gear – a black, full-length cassock, a dress-like garment with buttons from top to bottom, and a white cotta, a cotton and lace raglan-sleeved overshirt – and serving regularly on the altar. With the pleasant smells of incense and burning candle wax, coupled with the genuine feeling of spirituality I sometimes experienced, I liked it. But the thing I loved most was the fact that my mum was sitting in the congregation, watching and feeling proud of me. I believed wholeheartedly in God, and I felt sorry for non-Catholics, which was how I had been taught in school.

When the news came that I would soon be making my First Holy Communion, I was excited; God was to enter my soul. But first, it needed to be cleansed. The priest stressed that the process of confession was sacred – whatever was said between a priest and penitent in confession must remain secret and could not be repeated by the priest under any circumstances, even if the penitent had confessed to a murder. I loved the seriousness and importance of it. And I was so happy that I would be absolved of all my sins.

My first confession was with Father Burke. He was a close friend of the family, in that he was my Uncle Anthony’s pal through their priest college years and beyond; Uncle Anthony was my mum’s brother and also a priest. Father Burke was young and friendly, and I quite liked him, but I was disturbed by the way he shouted at Joe during altar practice.

I told Father Burke all the sins I could think of. The one I remember most is, ‘I stole biscuits from the tin at home.’ I left feeling cleansed and pure.

In those days it was commonplace for the local priest to call around to the parishioners’ homes unannounced. It was considered a privilege. Father Burke called round one evening and he sat in the living room, chatting with my parents and siblings after I went up to bed.

The next morning when I came down for breakfast, Mum said to me in a jokey tone, ‘We had a good laugh last night. Father Burke was telling us how you confessed to stealing the biscuits out of the tin.’

‘What? He told you what I said in confession? I thought it was supposed to be secret?’

‘Ah, it was only a few biscuits,’ Mum said.

Obviously, the biscuits weren’t the point! I was confused. I had thought this stuff was deadly serious. But I was far too young, at seven, to have a debate with anyone, or even a discussion about the rights and wrongs of the Catholic Church. It was a closed door, and holding on to any doubts about Father Burke or the church, or thinking that they were at fault in some way, was a non-starter in our house. The church was sacrosanct and beyond any kind of criticism or even questioning.

I ignored my experience and pushed it to the back of my mind. Ignoring my truths would be something I’d have a lot of practice at.

Punishment-wise, Dad would hit the boy children, but not the girls. It was called ‘the belt’.

My first experience of it came shortly after my eighth birthday. I had accidentally broken a banister on the stairs while we were playing.

‘You’re gonna get the belt tonight,’ one of my siblings said. And I did. My brother Joe was aggrieved that I’d been hit so soon after my birthday. ‘He shouldn’ta hit you two days after your birthday, Kev!’ Joe said in his Irish accent. Personally, I was mostly upset because the belting on my legs had damaged the paper trousers of my birthday present: a Davy Crockett outfit.

That night, Joe said we should run away. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to, or if Joe was serious, but I agreed. Very early the next morning, Joe woke me. We quietly got dressed – Joe in his grey shirt, multi-coloured V-neck slipover and grey shorts, with his big mop of blond curly hair; me with my blue sweatshirt, blue shorts and brown sandals. We gently sneaked out of the house and made our way to the centre of Wolverhampton. It was early morning, maybe 5am. The streets were deserted as we hit the usually busy Snow Hill. Through the early-morning mist, Joe saw a policeman walking towards us.

‘Come on, Kev – run!’

‘Hang on, Joe, I just wanna see if he’s got a ’tache,’ I said, for some unknown reason.

‘What? Come on, Kev. Run!’

‘Hang on, Joe. Just let me see if he’s got a ’tache.’

I guess, deep down, I must have been too scared to run away.

The policeman came up and asked us what we were doing out so early. Joe told him we were on a ‘cross-country run’. Naturally, the copper didn’t believe it; we were marched down to a police box at the bottom of the street, where he called for transport. A squad car appeared a few minutes later, and we were driven home by two policemen.

‘I found these two wandering around town,’ one of them said to our mum.

‘We went for a run, Mum,’ Joe said.

Now as I recall this, I wish I hadn’t stopped to see if the copper had a ’tache. I wish I’d gone with Joe. I don’t think we would have got very far, but I think if Mum and Dad had known that we’d actually ran away, they would have been shocked and it might have induced some reflection on

their part about how strict Dad was, which may have meant a softening that could have been beneficial to Joe and me.

• • •

Sam Cooke was singing about Cupid drawing back his bow. He was singing about another world. One that clearly existed, somewhere far, far away. It sounded romantic, exciting and beautiful.

Pat had a little transistor radio. I would lie under the blankets after my dad had turned out the light on a Sunday night, holding the radio close to my ear, listening to Radio Luxembourg, eagerly awaiting the week’s new releases. I’d try to memorise the melodies and lyrics. Then all I had to do was keep awake till Pat came in from the youth club, so I could sing them to him.

As well as music, Pat loved boxing.

‘You’re gonna be the heavyweight boxing champion of the world,’ he told me. He would buy The Ring magazine, and we would look at pictures of Floyd Patterson and Sonny Liston. Mum and Dad bought me a punchball for Christmas, and we trained hard. Pat would arrange informal fights for me with the local kids. He put a chart on my wall, ticking off whenever I beat a new opponent. The chart was all ticks. I had beaten all the other eight-year-olds in the street, as well as a nine-year-old.

Then one Saturday morning, as we walked home from weekly confession, we passed through the old buildings and saw an Indian kid coming towards us. The Indians and Afro-Caribbeans had recently arrived in the area and there were some tensions. We decided this Indian boy would be my next opponent. He was bigger and clearly older. That didn’t bother me; bolstered by Pat’s encouragement, I felt invincible.

‘’Ow old am ya, mate?’ I said.

‘Eleven,’ he replied.

Great, I thought. I’m going to do an 11-year-old.

‘Wanna foight?’

‘Yeah, all right.’

I wasn’t invincible. The boy gave me a proper pasting, and I went home with a bloody nose.

• • •

I loved the run-down terraced houses of Wolverhampton, the dark, decrepit, derelict buildings, the cheap posters on the walls advertising bands, the old cinema on the Dudley Road that had closed but still had the remains of a Zorro poster on its wall. I wondered what the film was like and if I’d ever see it.

I liked to watch the teenage boys sporting their quiffs and tight trousers, fags hanging out of their mouths. And I loved their neatly combed hair.

Dad had what I believe was a neurotic obsession with steering us away or protecting us – particularly me – from these things. He told me that I combed my hair too often.

As well as my own hair, I was also interested in other people’s. I would stand behind Dad’s armchair and comb his hair, which I think he just about tolerated. I got the impression that Dad thought my interests were sissy-ish. That caused confusion and later turmoil in me.

In 2010, during a relaxed conversation, I asked Dad why he told me that my interest in music and clothes was wrong. He said those were the things factory boys were interested in, and he was concerned I would become one. My intuition also told me that he had a concern about my sexuality. But I can’t be sure.

• • •

Mum rarely dressed up – but when she did, boy!

She was a hard worker, taking care of five kids without such conveniences as washing machines or dishwashers, and she was houseproud and would hardly ever stop and rest. In those days she smoked cigarettes and would often have an un-tipped Senior Service hanging from her mouth as she ironed our clothes. I loved the smell of those fags.

Although she owned nice clothes, she would only wear her very oldest stuff for ‘around the house’, as she called it, and of course she always seemed to be ‘around the house’.

The same philosophy was applied to her crockery, or ‘Delft’, as she called it. She had three sets: one that we would use every day, then a better set that would be brought out when visitors came, and also a third set (the very best) that was given pride of place in the cabinet but never used.

On the rare occasions she did go out, she would wear lovely tailored tweed skirt suits, with a white lace blouse that would highlight all her natural colouring. One of my mates said, ‘Your mum is so pretty!’ He was right – she had the kindest, brightest eyes. If we were in town and my face got dirty, she would pull out a clean hanky, wet it with her tongue and clean my face. I loved that.

My sisters and I went into my mum’s wardrobe one day and put on some of Mum’s clothes. We all came down to show her. I was wearing one of Mum’s dresses, which was of course way too big for me, as well as one of her hats. Mum didn’t object to my sisters wearing her clothes, but she clearly wasn’t happy that I was wearing them too. I don’t remember her exact words but I got the strong impression from Mum that she disapproved.

I couldn’t seem to second-guess my parents over what would be allowed and what wouldn’t. Nor was I skilled in asking for their permission at the right time and in the right way, like some of my siblings were. I seemed to always pick the wrong moment.

A friend and I bunked in to see a film, The Quiet Man. I’d told Mum I was going to the park. When we came out of the cinema, it was dark. My parents quizzed me on my return.

‘Where have you been?’

‘To the park.’

‘No, you haven’t. It’s been dark for an hour. Where have you been?’

‘To the park!’

‘Come on. The truth.’

After much toing and froing, finally I said, ‘OK, I went to the pictures.’

‘What to see?’

‘The Quiet Man.’

‘Well, why didn’t you tell us? We’d have let you go and see that film!’ I couldn’t work them out. The Quiet Man was a film that was set in the west of Ireland close to where my parents were from and held sentimental value for them.

Now it’s my last year of junior school, and some big changes are happening. Over a very short period of time, maybe three months, my brother Joe loses pretty much all of his confidence. He goes from being the most daring and wild boy in the school, to being the most shy, stuttering and withdrawn. He begins to walk with his head down and no longer speaks to anybody unless they first speak to him. It isn’t that he doesn’t want to speak to people, he just thinks they won’t want to speak to him. As to why that happened, I don’t know.

The other thing that happened was that it became my turn to get the pressure from Dad about the impending 11-plus exam. The pressure seemed even more intense than what Joe had gone through a few years earlier. It was an unceasing bombardment.

Dad would go on and on at me, raising his voice and ranting about how I must pass this exam. He was accusing me of being lazy, but I was doing all the work the teachers set. I didn’t know what I could do differently. I was good at English and OK at other subjects. There didn’t seem any way of getting Dad off my back. This exam was presented as a matter of life-or-death importance. If I didn’t get into the grammar school, it was the end of the world as far as Dad was concerned. From my point of view, the secondary modern school where most of my mates would be going, and where Pat and Joe went, looked attractive and relaxed.

There was no encouragement in Dad’s approach. It was all pressure. And it was far too much for me. In desperation one day, I said, ‘OK, I’ll pass it!’

Of course, I had no idea if I could.

Dad didn’t believe me, and sneered, ‘You’re not going to pass it!’ I felt that I just couldn’t win.

I don’t doubt that it’s possible I had a problem with concentration before Dad started applying this pressure, but I know for sure it got way worse after that. Schoolwork didn’t feel like it was even remotely for me; it was all about what Dad wanted. Any joy I had felt from learning disappeared. I had no interest whatsoever in passing the 11-plus, except to get Dad off my back.

I couldn’t seem to make my writing neat or keep my page clean, like a lot of the other kids could. It would start off neat, but I didn’t seem to be able to keep it that way. Another reason for my scruffy handwriting was that I had started off writing with my left hand, but was discouraged from doing so by the teacher, and ended up writing uncomfortably with my right hand, which has continued to this day.

When the teacher started talking about long division, I had absolutely no idea what she was talking about. I pretended that I did. From the age of ten onwards, I didn’t progress at maths at all. I would just sit in the classes, hoping not to be singled out. To this day, I have no idea how to do long division, long multiplication or most other mathematic equations.

Dad bought a car, and on summer Sunday afternoons, we would all go to Cannock Chase, an area of natural beauty on the outskirts of Wolverhampton. There were lots of families and couples there, and most would have their transistor radios tuned to the BBC Light Programme, the forerunner of Radio 1. We’d listen to Pick of the Pops, the weekly chart show hosted by Alan Freeman. I loved to hear all the hits and watch the young couples lying down and snogging.

‘Diamonds’ by Jet Harris and Tony Meehan would ring out of every transistor radio, sounding full of mystery and romance.

There was a Welsh kid in my class at school, called Nathan. He was only there for about three months, but I loved every moment with him. He was almost a year older than me, and he was music mad and knew the words to all the hit songs. He had a lovely voice. At every opportunity, Nathan and I and maybe another kid would sit together and sing songs in

the corner of the playground or in an alleyway. Then, if the teacher called for a performance during class, no problem – I’d comb my hair, walk up to the front of the class and happily sing any current chart hits or songs from musicals I’d seen with Pat and Joe. Singing was effortless and a joy to me. I couldn’t understand why some people found it difficult.

My plan at that time was to be like Pat and Joe – a teenager – and do all the exciting things they did. Then later I would be a pop singer or a guitarist. That plan seemed perfectly achievable.

I would look fondly at the musical instruments in the shop across the road. That Christmas, when I was ten, Mum finally bought me a guitar. I was delighted. I’d been pestering her for ages. It was an acoustic, with four strings.

She sent me for lessons to a man about a mile away from where we lived. His name was Honer Johnson. I’d walk there on Sunday afternoons, where there would be about half a dozen teenage boys, all playing away. The Beatles were just becoming massively popular and there was a big upsurge in people wanting to learn guitar and join bands. Every now and then, Honer would give one of us a scale or a chord sequence to learn. We would go into a corner of the room and practise it, making sure we understood the part before leaving. I was by far the youngest there and loved the feeling of being around the cool-looking teenage boys.

The lessons were very informal. Each of us might be there for as long as two hours, and then just before we left, we would give Honer our six shillings, which was a lot of money.

Honer said my four-stringed guitar wasn’t really suitable, and suggested I got a new one. He taught me to play the melody of ‘An English Country Garden’. And I just about learned a couple of scales, but I didn’t pick up any more. By this time, the guitar had become like maths – a mountain to climb – and I found I couldn’t focus long enough to learn. If the condition had been understood in those days, I know that I would have been diagnosed with attention-deficit disorder.

The church was a big part of our lives and it wasn’t unusual for me to serve two Masses on a Sunday, often at different churches. Joe and I would finish serving at St Teresa’s in Parkfields (our parish church) and then walk or get a bus a couple of miles into the centre of Wolverhampton to serve a Mass at St Mary and St John’s. We would also quite often serve a couple of Masses during the week before school.

At one Sunday Mass, they passed around leaflets that talked about a ‘vocation’. It was referred to as ‘the calling’. Every boy was directed to ask himself if he had ‘the calling’ from God to be a priest.

I asked Mum what happens if you want to be a priest.

‘Well, at 11, you go off to Cotton College. It’s a boarding school,’ she said.

That sounded exciting! My Uncle Anthony and Father Burke had gone there. I knelt in prayer and convinced myself that I was being ‘called’. I told my parents that I had the calling. Mum arranged for me to go and see the parish priest. He started to give me Latin lessons every Saturday morning at his house, in preparation for my years at Cotton College. Mum and I were also summoned to Birmingham to meet the bishop and to sit my entrance exam. It seemed to have gone well.

Of course, I’d already long decided I wanted to be a musician. And though I truly did enjoy the feeling of spirituality that I got sometimes from serving on the altar, or praying in church, I was aware that priests were celibate, and I knew even at that pre-pubescent age that I liked the warmth of girls and didn’t want to cut myself off from them. Also, a male schoolfriend and I would sometimes kiss in the playground, much to the amusement of the other kids.

But at ten years old, the thought that I’d have to be a priest at the end of the college years seemed like an eternity away, and the boarding school itself seemed like fun, whereas our house felt like a pressure cooker.

There was a record in the charts at the time called ‘Dominique’, by the Singing Nun. I asked my mum if I could be a singing priest.

I was genuinely torn. But the fact that Mum was proud of her ‘religious’ son was a massive factor in my decision, too. I wanted to make

her happy. Sometimes when I would hear her coming up the stairs in the morning, I’d quickly kneel so that when she walked in, she would see me praying.

But I was leading a double life. At home, I was a trainee priest and a good, prayerful altar boy. Elsewhere, I was compulsively thieving, lying, fighting, flirting with the girls and causing trouble. I was using the ‘fuck’ and ‘cunt’ words all the time with my mates. I was aware of my swearing and had tried to stop it, but was unable to. I was getting in a lot of trouble at school, and had a reputation as the naughtiest kid in the class, or at least in the top three.

Anybody who misbehaved would have to report to Mr Potts’ room after school for a caning. I seemed to end up there every single evening. I talked incessantly during lessons, played tricks, told jokes, talked about music, distracted other kids, passed love letters, or hummed, much to the annoyance of the teachers.

There was a tune in the charts called ‘Just like Eddie’, by Heinz. It was a great song and had a catchy hummed hook line: ‘Mm mm mm mm mm mm mm mm mmmmm.’

A couple of us would sit at the back of the class, and every time the teacher turned her head to face the blackboard, we’d start humming the tune, very softly, just loud enough that she could only vaguely hear it. At first, she would wonder if she was imagining it, turning her ear to listen.

To me, this situation was hilarious, and I couldn’t control my laughter. She soon realised who the culprits were, and we were in line for another caning.

Mr Potts (the cane king) was a big man and had an air of military-style, superior contentment about him. Prior to dishing out his punishment, he’d pace up and down the room, John Wayne-like, holding the cane horizontally across his chest, and bending it into an upside-down U shape to gain more flexibility. Simultaneously, he would be speaking to us about our wrongdoings in loud, slow and pronounced statements. ‘Rowland, Rossi, O’Brien, Atkins’ – the usual culprits – ‘you are in trouble, again!’ He seemed to relish the build-up as much as the caning itself.

My sister Grainne, 20 months my junior, was in a different class at the same junior school and it was my responsibility to take her home each day. As she was younger, her class was let out slightly earlier than mine, so she would come to my classroom and wait outside for me. One day, with no intention of humour or irony, she said to me, ‘Instead of coming to your classroom at the end of the day, I should go to Mr Potts’ room, because that’s where you always seem to be.’

‘He’ll always be a thief’

But now my two worlds are colliding and I have to tell Mum that the head nun wants her to go up to the school. The next 48 hours are a blur, but I remember the feeling of dread and horror. I also recall it was a Friday when Mum was summoned up to the school to be told by the head nun about my stealing. Instead of telling Mum the truth about why the nun wanted to see her, I just said:

‘Sister Pauline wants to see you.’

‘What for?’

‘I don’t know.’

I was trying to buy time.

My form teacher, another nun, Sister Mary Austin, had sobbed inconsolably, while looking at me with a mixture of scorn and terrible disappointment.

I was bad, and I was going to Hell.

When I got home that night, Mum too was very tearful and upset. She relayed to me that the head nun had told her, ‘He’ll never be any good – he’ll always be a thief.’

I suspect because I was going to a Cubs’ event the next day, Saturday, in my short trousers, I didn’t get dealt with by Dad that evening.

The Saturday-night family meal was sausages and mash. Normally, I would have enjoyed that dinner, but not that evening. I knew I was for it. I’d been pretending to myself that everything was OK and even tried to keep the jovial vibe going throughout the dinner. As we finished the food, the talk turned to my theft. Dad got angry.

‘You’re no more of a priest than my arse,’ he said.

He was right.

‘The rest of you, go out of the room. You wait here, Kevin.’ I got it.

It was decided between the school and my parents that I would

go back into the shop I had stolen the penny chew from, and tell them what I’d done – own up and give them the penny back.

That Monday morning, I walked into the shop, almost sick with fear. I planned to go up to the woman and tell her that I’d stolen the chew and was here to pay for it. But somehow, I couldn’t do it.

I secretly dropped a penny in the tray where the chews were kept and walked out of the shop.

When I was asked about it afterwards by my parents and the head nun, I told them I had apologised and given the shopkeeper the penny. They asked what she said. I told them she said, OK. I don’t know if they checked up, but I wasn’t challenged about it.

I think it would have been good for me to have spoken honestly to the shopkeeper. Mainly because there was way too much secrecy and lies going on in this ten-year-old boy’s head.

After having a serious talk with Mum, I resolved that I would be good, so that I wouldn’t end up in Hell like some of my mates.

When I would see them doing things that would likely land them in trouble, I started to walk away, just like my mum had told me. It was hard, because my old friends (the ‘bad boys’) were critical of my new stance, and although I was trying to not do what they were doing, we were still half hanging around together. I didn’t have any new friends. I was in no-man’s land.

They didn’t seem to trust me. I wanted to be mates with them and do all the exciting stuff, but the fear of breaking my mother’s heart and going to Hell was the dominant force. It was a lot of stress.

Myself and three of the other ‘bad boys’ found our way into the school storeroom one lunchtime. We came across a big box of ink powder (in those days ink was delivered in powder, for the caretakers to mix with water). Giuseppe Rossi started splashing the powder around. I could see immediately that this was going to lead to big trouble and I bolted in a panic.

An hour later, one of the girls reported to Mr Potts that she had been walking through the corridor, when a gust of ink powder descended on

her, soiling her nice summer dress. The ink had been thrown at her from above.

That afternoon, Mr Potts strode into our classroom and bellowed sarcastically, ‘Some boys have stolen ink powder from the storeroom and have ruined Madelaine Fielding’s dress!’

Then, with a weary air of resignation, he half sighed and half shouted, ‘Rowland … Rossi … O’Brien … Atkins, step this way, gentlemen!’

The other three got up and walked towards him. I stayed where I was.

‘Rowland!’ he said again loudly, looking away expectantly and confidently.

‘No, sir,’ I said.

‘No, sir, what?’ he shouted sarcastically.

‘I wasn’t there, sir.’

I felt a vague sense of pride.

A few days later, during lunch hour, the same guys (Rossi, O’Brien, Atkins and myself) wandered into the big church next door to the school. We weren’t supposed to leave the playground. A brand-new public-address system had just been installed to amplify the priest’s sermons. It was the first time the church had used electronic equipment, and a big deal. We went up into the pulpit. I was fascinated by the microphone. This was the closest I’d been to one. Rossi hit the switch. The red ‘On’ light lit up, and a big boom sounded out, letting us know that the system was ready for use. Immediately, Giuseppe started singing:

Close your eyes and I’ll kiss you, tomorrow I’ll miss you

Total panic came over me, with an intensity that I hadn’t ever before experienced. This was sacrilege! A pop song sung down the priest’s microphone, in church! That would surely mean Hell. And I knew that my mother and the nuns would be absolutely horrified. I ran out of the church as fast as I could.

After that the lads, particularly Rossi and O’Brien, started blanking me and taking the piss out of me. I either mentioned it to my mum,

though I don’t remember it, or perhaps my sister told her, because shortly after, as the other kids and I were walking down from the school to the bus stop, I was surprised to see Mum walking towards us. She went straight up to O’ Brien, Rossi and the others.

‘I’m disappointed in you all,’ she said. ‘The rats desert a sinking ship!’ They tried to walk away, so as not to hear her. But she kept walking fast too.

I cringed with embarrassment at the time, but I’m touched by it now.

Shortly after, I had a disagreement with Rossi in the classroom, and it was decided that we would have a fight after school.

I had previously been pretty sure I could beat him – whenever we’d had mock fights, I always came out on top, overpowering him in some way, or punching harder, as I did with the vast majority of the kids in my class. Up to that point, I had probably been the best fighter in the gang. But now I was nervous.

As my little sister Grainne stood watching the fight, I lost, badly.

The strange thing is, six months earlier, I know I would have beaten him. But now, as I look back, I think the stress was making me physically as well as mentally weaker.

I started to not want to go to school. I was no longer popular and felt quite alone. I started to fake illness. My acting succeeded once or twice, but eventually my mum got wise. I remember walking out of the house one morning, getting as far as the bus stop, then thinking, Fuck it. I can’t go to school today.

I turned back home. My mum wasn’t happy when I walked back into the kitchen and pronounced myself ill. She knew I was swinging the lead and sent me back out to the bus stop.

The way I found out that I hadn’t been accepted to the priest college was odd and unpleasant.

I served Mass on the Saturday morning as usual, with my friend Graham. He had also applied to go to the college. Graham was late for Mass that day and joined Father Burke and me at the altar after the service had started. After the Mass, as we took off our cassocks and cottas, Graham happily told Father Burke that he had received his acceptance letter that morning.

Father Burke smiled and said, ‘I know you have. Well done.’

‘Have you heard anything about me getting in, Father?’ I asked excitedly.

‘No, I haven’t. Why don’t you go home? Maybe the letter is waiting there for you.’

I ran home. Mum was in the kitchen (the scullery, as she called it).

‘Mum, did you get the letter from Cotton College about me getting in?’

‘No, we haven’t had a letter.’

‘Ah, damn. Graham Southall got his, and he’s got in!’

‘Well, maybe it’ll be here on Monday,’ she said.

A few days later, Mum took me aside and told me I hadn’t got in. I was down about it, and confused. My exam results weren’t terrible at this point – only just below Graham’s. And I was pretty good at spelling, better than most of the kids in the class. Also, I knew that there was a desperate shortage of priests.

I didn’t put it together at the time that it must have been the stealing at school that was the deciding factor. The authorities at Cotton College would surely have written to Sister Pauline for a reference. She had told my mother that I would never be any good. Why would she tell the college anything different?

I spoke to my mum about this in the early 2000s and she said that she too was surprised that I didn’t get in. But both Mum and Dad also told me that they hadn’t taken my priest vocation too seriously, quite correctly, of course.

I can also now recall Father Bullen (the parish priest) getting exasperated at me for not grasping the Latin that he was trying to teach

‘he’ll

me in the Saturday-morning lessons. Graham was much better at it. So maybe I failed the exam. I was finding it harder and harder to concentrate and take in new information.

Graham went on to study at Cotton College, where he got a good education until he was 16. To my knowledge, though, he never became a priest. I ended up failing the 11-plus.

There was already talk of our family moving to London. My dad was so highly thought of at his work that in 1964 the company said they wanted to move him and the rest of us to London, to a much bigger contract, and to promote him to a site agent. It sounded exciting, but I was doubtful that it would happen. I couldn’t imagine it. I’d heard Cockneys speaking on TV – they sounded funny, but good. Sister Mary Austin, my form teacher, had told us it was an awful place, that the children there never saw a blade of grass. What’s so special about seeing blades of grass? I wondered.

That summer, 1964, we went on a family holiday to County Mayo in Ireland, where Mum and Dad were from. It was the first time we had been back to Ireland since we came over when I was four. We rented a cottage in Enniscrone, on the Sligo/Mayo border.

On the way over, we stopped off in Dublin. For some reason, just myself and my mother went to the post office in O’Connell Street, on a lovely sunny day. Mum looked pretty and brown on that day, as she always did in the summer. She showed me the bullet holes in the wall where the 1916 rebels had boarded themselves in, proclaiming an Irish Republic and an end to British rule. I was touched by it, and I could see Mum was proud of our history.

It was my first real knowledge of Ireland’s past, apart from a night at a church ‘social’ in Wolverhampton, where my Uncle Mick and other relatives had come over from the other side of town. I remember looking around the smoke-filled, beer-bottle-strewn hall, at the many dark, sad Irish faces. There was something different about them.

The song ‘Kevin Barry’ came on and everyone sang along. Mum hugged me and told me, ‘ We’re not allowed this song in England.’

‘Why, Mum?’

‘Because it’s about what the English did to the Irish.’

I was shocked that a song could be banned. And I was excited that we were all locked away in this smoky church hall, secretly singing a rebel song.

It was a scorching-hot day in late August 1964 when all seven of us squeezed into dad’s MG Magnette for the journey to north-west London. As we approached Watford, ‘Things We Said Today’ by the Beatles came on the radio.

Someday when we’re dreaming, deep in love, not a lot to say

Then we will remember, things we said today.

It was barely audible through the interference, but the minor-sounding melody and deadpan vocal delivery seemed to perfectly fit the lateafternoon mood.

‘Are we in London yet?’ (I’d never been before.)

‘Yeah,’ Pat said, ‘on the outskirts.’

I didn’t believe him. It didn’t look any different to Wolverhampton. I thought London would be all big buildings, but these were normal houses, with front gardens, and grass! Plenty of it!

And besides, I’d just seen a kid walking down the street wearing an orange Wolves shirt. I was convinced we were still in Wolverhampton. I found out later that we were in Watford and, at that time, Watford FC’s shirt was almost identical to the Wolves top.

In five days I was due to start secondary school. I had just turned 11.

St Gregory’s was a big step up from St Mary and St John’s, my Wolverhampton junior school. The standard of education was higher. There were hardly any scruffy kids, and the few that were got hell from the others. Fortunately, Mum made sure we were always immaculately turned out, but I soon started to cop it, for other reasons.

It started in a drama class (I’d never even heard of drama previously), a few days after I’d arrived. A general election was about to