EX LIBRIS

VINTAGE CLASSICS

JULIO CORTÁZAR

Julio Cortázar lived in Buenos Aires for the first thirty years of his life, and, after that, in Paris. His stories, written under the dual influence of the English masters of the uncanny and of French surrealism, are extraordinary inventions, just this side of nightmare. In later life, Cortázar became a passionate advocate for human rights and a persistent critic of the military dictatorships in Latin America. He died in 1984.

GREGORY RABASSA

Gregory Rabassa translated many classic works of modern Spanish and Portuguese literature, including One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez. His translation of Hopscotch received the National Book Award for Translation.

also by julio cortázar

A Certain Lucas

A Change of Light and Other Stories

All Fires the Fire

Bestiary

Around the Day in Eighty Worlds

Autonauts of the Cosmoroute

Blow-Up and Other Stories

Cronopios and Famas

Diary of Andrés Fava

Divertimento

Fantomas Versus the Multinational Vampires

Final Exam

From the Observatory

Hopscotch

Literature Class, Berkeley 1980

Nicaraguan Sketches

Save Twilight

62: A Model Kit

Someone Walking Around

The Winners

Unreasonable Hours

We Love Glenda So Much and Other Tales

julio cortázar

A MANUAL FOR MANUEL

tra N slat ED F ro M t HE s P a N is H by

Gregory Rabassa

Vintage Classics is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies

Vintage, Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London s W11 7 b W

penguin.co.uk/vintage-classics global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright © Julio Cortázar, 1973, and Heirs of Julio Cortázar English translation copyright © Random House, Inc., 1978

The moral right of the author has been asserted

First published with the title Libro de Manuel by Editorial Sudamericana Sociedad Anónima in 1973

First published in the United States of America by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 1978

This paperback first published in Vintage Classics in 2025

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isb N 9781529956795

Typeset in 11/13pt Bembo Book MT Pro by Six Red Marbles UK, Thetford, Norfolk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 y H68

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

For obvious reasons I am probably the first one to discover that this book not only doesn’t seem to be what it wants to be, but that frequently it also seems to be what it doesn’t want to be, and so proponents of reality in literature are going to find it rather fantastical while those under the influence of fiction will doubtless deplore its deliberate cohabitation with the history of our own times. There is no doubt that the things taking place here cannot possibly take place in such a strange way, while elements of the purely imaginary are seen to be eliminated by a frequent slipping into what is everyday and concrete. Personally, I have no regrets concerning this heterogeneity which, fortunately, no longer seems to be such to me after so long a process of convergence; if, over the years, I have written things that are concerned with Latin American problems along with novels and tales where these problems were missing or only tangential in their appearance, at this time and in this place these streams have merged, but their conciliation has not been easy in the least, as can be shown, perhaps, in the confused and tormented path of some character or other. This man is dreaming something I had dreamed in a like manner during the days when I was just beginning to write and, as happens so many times in my incomprehensible writer’s trade, only much later did I realize that the dream was also part of the book and that it contained the key to that merging of activities which until then had been unlike. Because of things like that, no one should be surprised by the frequent inclusion of news stories that were being read as the book was taking shape: stimulating coincidences and analogies caused me from the very start to accept a most simple rule of the game, having the characters take part in those daily readings of Latin American and French newspapers. I was innocent enough to

hope that such participation would influence their behavior more openly; only later on did I begin to see that the story as such would not always fully accept those fortuitous intrusions, which really deserve a more felicitous experimentation than mine. In any case, I did not choose the external materials, rather, the Monday and Thursday news that became of momentary interest to the characters was incorporated into the course of my work on Monday and Thursday; some few items were deliberately set aside for the last part, an exception that made the rule more tolerable.

Books should take care of their own defense, and this one does so like a cat on his back with his belly up every chance it gets; I only wish to add that its general tone, which goes against a certain concept of how these themes should be treated, is as far removed from frivolity as it is from gratuitous humor. I believe more than ever that the struggle for socialism in Latin America should confront the daily horror with the only attitude that can bring it victory one day: a precious, careful watch over the capacity to live life as we want it to be for that future, with everything it presupposes of love, play, and joy. The widely circulated picture of the American girl offering a rose to soldiers with fixed bayonets is still evidence of the distance that lies between us and the enemy; but let no one understand or pretend to understand that that rose is a Platonic sign of nonviolence, of innocent hope; there are armored roses, as the poet saw them, there are copper roses, as Roberto Arlt invented them. What counts and what I have tried to recount is the affirmative sign that stands face to face with the rising steps of disdain and fear, and that affirmation must be the most solar, the most vital part of man: his playful and erotic thirst, his freedom from taboos, his demand for a dignity shared by everybody in a land free at last of that daily horizon of fangs and dollars.

Otherwise, it was as if the one I told you had intended to recount some things, for he had gathered together a considerable amount of notes and clippings, waiting, it would seem, for them to end up all falling into place without too much loss. He waited longer than was prudent, evidently, and now it was Andrés’s turn to find out about it and be sorry, but, apart from that mistake, what seemed to have held the one I told you back the most was the heterogeneity of the backgrounds where all those things had taken place, not to mention a rather absurd desire, one not at all functional in any case, not to get too involved in them. That neutrality had led him from the beginning to hold himself as if in profile, an operation that is always risky in narrative matters – and let us not call it historical, which is the same thing, especially since the one I told you was neither foolish nor modest – but something hard to explain seemed to have demanded that he assume a position he was never disposed to give details about. On the contrary, even though it wasn’t easy, he preferred from the start to dole out diverse facts that would permit him entry from different angles into the brief but tumultuous history of the Screwery and people like Marcos, Patricio, Ludmilla, or me (whom the one I told you called Andrés without straying from the truth), hoping, perhaps, that that fragmentary information would someday shed light on the inner kitchen of the Screwery. All this, of course, so that all those notes and scraps of paper would end up falling into an intelligible order, something that didn’t really happen completely for reasons that could be deduced to some degree from the documents themselves. One proof of his intention to get into the material at once (and perhaps to point up the difficulty of doing it) was provided, inter alia, by the fact that the one I told you had been

listening when Ludmilla, after clasping and unclasping her hands in what looked like a rather esoteric gymnastic exercise, looked at me slowly with the help of her deep green ocular equipment and said Andrés, I get a feeling down near my stomach that everything that happens or happens to us is quite confusing.

‘Confusion is a relative term, Polonette,’ I pointed out to her. ‘We understand or we don’t understand, but what you call confusion isn’t responsible for either one of the two. It seems to me that understanding depends on us alone, and that’s why you can’t measure reality in terms of confusion or order. Other forces are missing, other options, as they say nowadays, other mediations as they archsay nowadays. When they talk about confusion, what they almost always mean is confused people; sometimes all that’s needed is a love, a decision, an hour outside the clock so that all of a sudden fate and will can immobilize the crystals in the kaleidoscope. Etc.’

‘Bloop,’ said Ludmilla, who would use that syllable when she wanted mentally to cross over to the opposite sidewalk – and try to catch her.

Naturally, the one I told you observes, in spite of such subjective obstructionism, the underlying theme is quite simple: (1) Reality exists or it doesn’t exist, in any case it’s incomprehensible in its essence, just as essences are incomprehensible in reality, and comprehension is another mirror for larks, and the lark is a birdy, and a birdy is a diminutive of bird, and the word bird has one syllable and four letters, and that’s how reality can be seen to exist (because larks and syllables) but it’s incomprehensible, because, furthermore, what do we mean by mean, or, among other things, by saying that reality exists. (2) Reality may be incomprehensible, but it does exist, or at least it’s something that happens to us or that each of us makes happen, so that a joy, an elemental necessity, makes us forget everything said (in 1), and on to (3). We’ve just accepted reality (in 2), whatsoever or howsoever, and consequently we accept our being installed in it, but right there we know that, absurd or false or trumped up, reality is a failure for man even though it may not be for the birdy, who flies without asking any questions and dies without knowing it. Therefore, inexorably, if we end up accepting what was said in (3), we have to pass on to (4). This reality, on the level of (3), is a fraud and we have to change it. Here we have a divergence, (5a) and (5b):

‘Oof,’ says Marcos.

(5a) To change reality for me alone – the one I told you goes on – is something old and feasible: Meister Eckhart, Meister Zen, Meister Vedanta. To discover that the I is an illusion,

to cultivate one’s garden, be a saint, overtake the sacred prey, etc. No.

‘You’re getting there,’ says Marcos.

(5b) To change reality for everyone – the one I told you goes on – is to accept the fact that everyone is (ought to be) what I am, and, in some way, to meld the real with mankind. That means admitting history, that is, the human race on a false course, a reality accepted until now as real, and away we go. Consequence: there’s only one duty and that’s to find the true course. Method: revolution. Yes.

‘Wow,’ Marcos says, ‘you’re the best there is for simplistics and tautology.’

‘It’s my little red morning book,’ the one I told you says, ‘and you’ve got to admit that if everybody believed in simplistics like that it woldn’t be so easy for Shell Mex to put a tiger in your tank.’

‘That’s Esso,’ says Ludmilla, who owns a two-horsepower Citroën where the horses seem to become paralyzed with fear of the tiger, because they stop on every corner and the one I told you or I or somebody has to push it along.

The one I told you likes Ludmilla because of her crazy way of seeing anything at all, and probably for that reason, from the outset Ludmilla seems to have a kind of right to violate all chronology; if it’s true that she’s been able to talk to me (‘Andrés, I’ve got an impression at stomach level . . .’), on the other hand, the one I told you mixes up their roles, deliberately perhaps, when he makes Ludmilla talk in the presence of Marcos, because Marcos and Lonstein are still on the Métro that’s bringing them, it’s true, to my apartment, while Ludmilla is playing her part in the third act of a dramatic comedy at the Théâtre du VieuxColombier. This doesn’t matter in the least to the one I told you, for two hours later the persons mentioned will have come together at my place; I even think that he decides it on purpose so that no one – including us and most especially the eventual recipients of his praiseworthy efforts – will have any illusions about his way of dealing with time and space; the one I told you would like to dispense with simultaneity, show how Patricio and Susana are bathing their child at the same moment that Gómez the Panamanian, with visible satisfaction, is filling in a set of Belgian stamps, and a certain Oscar in Buenos Aires is phoning his friend Gladis to tell her about some very grave matter. As for Marcos and Lonstein, they’ve just come into bloom on the surface of the fifteenth arrondissement in Paris and they light their cigarettes with the same match, Susana has wrapped her son up in a blue towel, Patricio is preparing a drink of mate , people are reading the evening papers, and so on.

Ludmilla

Gómez

Monique

Lucien Verneuil

Heredia

Marcos

Andrés

The one I told you [Francine]

Oscar Manuel

Gladis

Lonstein

Roland Fernando

So as to shorten the introductions, the one I told you thinks of something like this, suppose that everyone is sitting more or less in the same file of theater seats facing something which could be, if you wish, a brick wall; it’s not difficult to imagine that the show is a long way from being anything colorful. Anyone who buys a ticket has the right to a stage where things happen and a brick wall, except for the more or less fortuitous passage of a cockroach or the shadow of someone coming down the center aisle looking for his seat, doesn’t go very far. Let us admit, then – all this in the care of the one I told you, Patricio, Ludmilla, or myself, not to mention the others who, little by little, are coming along to sit in the seats farther to the rear, the way the characters in a novel take their places one after the other in the pages that lie ahead – although how can you tell in a novel which pages are the ones that lie ahead and which the pages to the rear since the act of reading is to proceed ahead in the book, while the act of appearing is to go back in relation to those who will appear later on, details of form that are of no importance – let us admit, then, to a complete absurdity and yet those people are still there, each in his seat facing the brick wall, for different reasons since it’s a question of individuals but something which in some way goes against the grain of the absurd, as illogical as it may seem to the inhabitants of the neighborhood who at that same moment in the movie down the block are watching with fascination the sensational Made in USSR production of War and Peace in Technicolor and two parts and wide screen, supposing that those attending might suppose that the one I told you, et al., are sitting in their seats facing a brick wall,

and being against the grain of the absurd means precisely that Susana, Patricio, Ludmilla, et al., are where they are, because that kind of metaphor into which they have all got themselves knowingly and each in his own way means, among other things, not seeing War and Peace (continuing with the metaphor, because at least two of them have already seen it), knowing very well where they are, knowing even better that it is absurd, and knowing on top of everything that they cannot be violated by the absurd to the degree that they not only face it (sitting down in front of the brick wall, metaphor) but that the absurdity of heading in the direction of the absurd is exactly what brings down the walls of Jericho, who cares if they were made of brick or pressed tungsten, if it fits the case. Or if they go against the grain of the absurd because they know it’s vulnerable, conquerable, and that underneath it all it’s enough to shout in its face (of bricks, continuing the metaphor), which is nothing but the prehistory of man, his amorphous projection (here innumerable possibilities for theological, phenomenological, ontological, sociological, dialectic-materialist, pop, hippie descriptions) and it’s over, this time it’s over, no one really knows how, but at this point in the century something is over, brother, and then let’s see what happens, and for that reason precisely tonight, in what’s done or what’s said, in what will be said or done by so many who are still coming in and sitting down facing the brick wall, waiting, as if the brick wall were a painted curtain that will go up as soon as the lights go out, and the lights do go out of course, and the curtain doesn’t go up arch-of-course, because-brick-walls-don’t-go-up. Absurd, but not for them because they know that it’s man’s prehistory, they’re looking at the wall because they suspect what might be on

the other side; poets like Lonstein will talk about the millenary kingdom, Patricio will laugh in its face, Susana will think vaguely about a happiness that doesn’t have to be bought with injustice and tears, Ludmilla will remember, without knowing why, a little white dog that she would have liked to have had when she was ten and which they never gave her.

As for Marcos, he’ll take out a cigarette (it’s not permitted) and will smoke it slowly, and I will put all those things together in order to imagine a way out through the bricks for mankind, and naturally I will never get to imagine it because extrapolations from science fiction bore me in detail. Finally we will all go and drink beer and mate at Patricio and Susana’s, something will really start to happen at last, something yellow cool green liquid hot in mugs gourds placed in a circle and sucking tubes and seeming to fly over the imposing mountain of sandwiches that Susana and Ludmilla and Monique will have prepared, those mad maenads, always starving when they come out of the movies.

‘Translate,’ Patricio commanded. ‘Can’t you see that Fernando’s fresh off the boat and that Chileans for the most part haven’t got the gift of Gallic gab.’

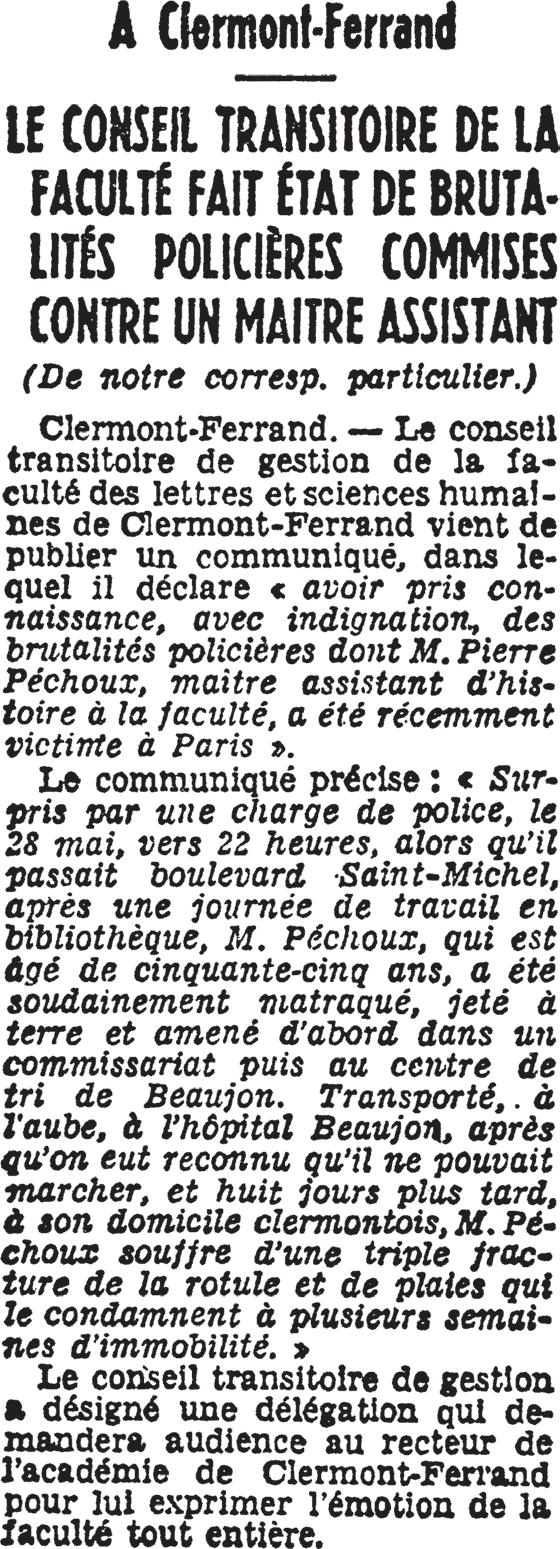

‘You’ve got me confused with Saint Jerome,’ Susana said. ‘All right. Clermont-Ferrand.

Provisional Faculty Council protests act of police brutality against adjunct professor. By our special correspondent.’

‘A summary will be fine for me,’ Fernando said.

‘Shh. Clermont-Ferrand. The Provisional Administrative Council of the Faculty of Letters and Human Sciences of Clermont-Ferrand has just released a statement in which it declares, quote, that it has learned with indignation of the act of police brutality of which Mr Pierre Péchoux, Adjunct Professor of History on the Faculty, was victim in Paris. Unquote. The statement follows, quote, caught up in a

police charge on May 28 at about 10 P.M. while walking along the Boulevard Saint-Michel after a session of work in the library, Mr Péchoux, 55, was suddenly attacked with clubs, knocked to the ground, and taken to a police station, from where he was transferred to investigation headquarters in Beaujon. At dawn he was removed to the Beaujon Hospital when it was noted that he was unable to walk, and a week later he was returned to his home in Clermont-Ferrand. Mr Péchoux suffered a triple fracture of the kneecap and other injuries that will require him to be completely immobilized for several weeks. Unquote. The Provisional Administrative Council has named a delegation to seek a hearing with the president of the University of Clermont-Ferrand to express the faculty’s indignation.’

‘So they’ve got the hospital right next to investigation headqvarters,’ Fernando said. ‘Vell-organized, these Frenchmen. In Santiago things are alvays tventy blocks avay from each other.’

‘Now you can see why it was useful to have the item translated,’ Patricio said.

‘It’s obvious,’ Susana conceded. ‘Now you can finally see what’s waiting for you in the land of the Marseillaise, especially along the Boulevard Saint-Michel.’

‘And that’s just vhere my hotel is,’ Fernando said. ‘Vone thing, though, I’m not an adjunct professor. So they beat up on profs here. It’s still something positive, leaving out the barbarism. Poor old Pechú.’

The phone rang, it was I, telling Patricio that Lonstein and Marcos had just come by, could we run over with Ludmilla and them to talk, we’ve got to fraternize from time to time, don’t you think?

‘This is no time to call, damn it,’ Patricio said. ‘I’m in a very important meeting. No, dummy, you should have been able to tell by my voice, a person’s voice always pants a little in cases like this.’

‘I bet he’s telling you a dirty story,’ Susana said.

‘You’ve got it, baby. What? No, I was talking to Susana here and a Chilean who got in a week ago, we’re giving him an

indoctrination course in the environment, if you follow me, the guy’s still pretty much of a hick.’

‘You can go to hell along vith the vone you’re talking to,’ Fernando decreed.

‘That’s the way,’ Susana said. ‘While those two are exploiting Alexander Graham Bell, you and I will fix some mate with the yerba Monique stole from Fauchon.’

‘Sure, come on over,’ Patricio gave in. ‘My remarks were of a disciplinary nature, don’t forget that I’ve got fifteen years in this country and it leaves its mark, chum. They’re Argentines,’ he explained to Fernando who had already figured that out for himself. ‘We have to amene them as we say in France, because Marcos probably has some fresh news from Grenoble and Marseilles, where there was a donnybrook between the gauchists and the cops last night.’

‘Gavchists?’ asked Fernando, who had palate problems. ‘Are there gavchos in Marseilles?’

‘You have to understand that translating gauchiste by leftist wouldn’t give you the precise idea, because in your country and in mine it means something quite different.’

‘You’re going to get him all confused,’ Susana said. ‘I don’t see that much difference, the trouble is that with you the word leftist is like a weak mate because of your younger days with the People’s Cause and things like that, and while we’re on the subject, take this one, I just brewed it.’

‘You’re right,’ Patricio said, meditating with the sipper in his mouth as Martín Fierro would have done under similar circumstances. ‘Leftist or Peronist or whatever comes next hasn’t had any very clear meaning for years now, but while we’re at it, translate that other item on the same page for the fellow.’

‘Another translation? Didn’t you hear Manuel wake up and demand his hygienic care? Wait till Andrés and Ludmilla get here, they can learn a little contemporary history along the way while they translate.’

‘All right, go take care of your son; the trouble with the kid is

hunger, girl, bring him here and bring the bottle of grappa on the way, it’s good for the mate.’

Fernando was doing his best to decipher the headlines in the paper and Patricio watched him with bored sympathy, wondering whether or not he shouldn’t find some pretext to get rid of him before Marcos and the others got there, lately the vise had been tightening on the Screwery and he didn’t know too much about the Chilean. ‘But Andrés is coming and Ludmilla of course,’ he thought. ‘We’ll talk about everything else under the sun except the Screwery.’ He handed him another mate without ideological content, waiting for the doorbell to ring.

Yes, of course there’s a mechanism, but how do you explain it and, after all, why explain it, who’s asking for an explanation, questions that the one I told you brings up every time people like Gómez or Lucien Verneuil look at him with raised eyebrows, and one night I was able to tell him that impatience is the mother of all who get up and go out slamming a door or a page, then the one I told you sips his wine, sits looking at us for a while, and then condescends to state or only to think that the mechanism is in some way the lamp that is lighted in the garden before people come to dine in the cool air amidst the smell of jasmines, the perfume that the one I told you had come to know in a town in Buenos Aires province a long time back when his grandmother would get out the white tablecloth and set the table under the arbor near the jasmines and someone lighted the lamp and there was a sound of silverware and plates on trays, talking in the kitchen, the aunt who would go to the alley with the white gate to call the children who were playing with their friends in the garden next door or on the sidewalk, and there was the heat of a January evening, grandmother had watered the garden before it grew dark and you could get the smell of the wet earth, the thirsty privets, the honeysuckle covered with translucent drops that multiplied the lamp for a child with eyes born to see things like that. All of that has little to do with today after so many years of a good life or bad, but it’s good to let yourself fall into an association that will tie in the description of the mechanism to the lamp in the summer garden of childhood, because in that way it will come to pass that the one I told you will receive a particular pleasure in talking about the lamp and the mechanism without feeling too theoretical, simply recalling a past that becomes more present every day due to sclerosis or reversible time,

and at the same time he’ll be able to show how what’s starting to happen now for someone who’s probably getting impatient is a lamp being lighted in a summer garden on a table in the midst of plants. Twenty seconds will pass, forty, a minute, perhaps, the one I told you remembers the mosquitoes, the praying mantises, the inchworms, the beetles; it’s easy to figure out the simile, first the lamp, a naked single light, and then the other elements begin to come, the scattered pieces, the shreds, Ludmilla’s green shoes, a turquoise penguin, the beetles, the mantises, Marcos’s curly hair, Francine’s panties, so white, a certain Oscar who brought some royal armadillos, not to mention the penguin, Patricio and Susana, the ants, taking shape and the dance and ellipses and crosses and bumping and rapid pecking on the butter plate or the platter of manioc flour, with shouts from mother who asks why they didn’t put a napkin over it, she can’t believe they don’t know that nights like this are full of bugs, and Andrés called Francine bug once, but maybe the mechanism is being understood now and there’s no reason to let yourself be carried off by the entomological whirlwind ahead of time; it’s just that it’s nice, nicely sad not to leave that point without looking back for a second at the table and the lamp, looking at grandmother’s gray hair as she serves dinner, the dog as she barks because the moon has come up and everything quivers among the jasmines and the privets while the one I told you turns his back and the forefinger of his right hand rests on the key that will print a hesitant, almost tired period at the end of what is beginning, or what had to be said.

For his part and in his way, Andrés, too, was looking for explanations of something that he was missing as he listened to Prozession ; the one I told you ended up being amused by that obscure reverence for science, the Hellenic heritage, the insolent why of everything, a kind of return to Socratic ways, a horror of mystery, of things happening and being accepted just because; he suspected the influence of a powerful technology rising up with a more legitimate view of the world, aided by the philosophies of left and right, and then he would defend himself with freshly watered jasmines and privets, weakening on one side the requirement that the clockwork of things be shown, but offering an explanation that few would find plausible. In my case the matter was less rigorous, my problem that night before Marcos and Lonstein arrived to break my back, goddamned Cordovans (the Argentine city, not the Spanish one, of course), was to understand why I couldn’t listen to the recording of Prozession without alternately being distracted and concentrating on it, and a fair amount of time had passed before I realized that it was being done on the piano. So that’s how it is, I only have to replay a part of the record to corroborate it; in the midst of the electronic sounds or traditional sounds modified by Stockhausen’s use of filters and microphones, from time to time, with great clarity, you can hear the piano with its own sound. So simple, really: old man and new man in this same man placed strategically to close the triangle of stereophony, the breaking of a supposed unity that a German musician had stripped naked in a Paris apartment at midnight. That’s how it is, in spite of so many years of electronic or contingent music, of free jazz (good-by, good-by to melody, and good-by to old defined rhythm too, to closed forms, good-by to sonatas, good-by

to chamber music, good-by to wigs, to the atmosphere of tone poems, good-by to the foreseeable, good-by to the dearest part of custom), all the same, the old man is still alive and remembers, in the headiest of adventures we have the easy chair, as always, and the archduke’s trio, and suddenly it’s so easy to understand: the piano had coagulated sounds that had merely survived before, so in the midst of a complex of sounds where everything is discovery, the color and tone of the piano appear like old photographs, and even though the piano can give birth to the least pianistic of notes or chords, the instrument is recognizable here, the piano of the other music, an older mankind, an Atlantis of sound in a full, young, new world. And yet it’s easier now to understand how history, the temporal and cultural conditioning, becomes fulfilled, for every passage where the piano dominates sounds to me like a recognition that brings my attention into concentration, awakens me more sharply to something that is still tied to me by that instrument which acts as a bridge between past and future. The not very friendly confrontation between the old man and the new: music, literature, politics, the cosmovision that takes them all in. For contemporaries of the harpsichord, the first appearance of the sound of the piano must have slowly awakened the mutant that today has become traditional vis-à-vis the filters manipulated by that German so that he can fill my ears with sibilants and other chunks of sound never heard before anywhere under the moon. Corollary and moral: everything should be a leveling off of attention, then, a neutralizing of the extorsion of those outbreaks from the past in the new human way of enjoying music. Yes, a new way of being that tries to include everything, the sugar crop in Cuba, love between bodies, painting and family and decolonization and dress. It’s natural for me to wonder again about the problem of building bridges, how to seek new contacts, the legitimate ones, beyond the loving understanding of different generations and cosmovisions, of a piano and electronic controls, of dialogues among Catholics, Buddhists, and Protestants, of the thaw between two political blocs, of peaceful coexistence; because it’s not a question

of coexistence, the old man can’t survive just as he is in the new one even though man continues to be his own spiral, the new spin in the interminable ballet; it’s no longer possible to talk about tolerance, everything is speeding up to a sickening degree, the distance between generations grows in geometric proportion, nothing to do with the twenties, the forties, pretty soon the eighties. The first time a pianist stopped his playing to run his fingers over the strings as if it were a harp or beat on the case to mark a rhythm or a pause, shoes flew onto the stage; now young people are surprised if the sonorous uses of a piano are limited to its keyboard. What about books, those shabby fossils in need of an implacable gerontology, and those ideologues of the left who doggedly insist on an only slightly less than monastic ideal of private and public life, and those on the right unmoved in their disdain for the millions of dispossessed and alienated? A new man, yes: how far away you are, Karlheinz Stockhausen, most modern musicmaker mingling a nostalgic piano with full electronic iridescence; it’s not a reproach, I’m telling it to you from my own self, from the easy chair of a fellow traveler. You’ve got the bridge problem too, you have to find the way of speaking intelligibly when, perhaps, your technique and your most deeply installed reality are demanding that you burn the piano and replace it with some other electronic filter (a working hypothesis, because it’s not a question of destroying for destruction’s sake, more than likely the piano serves Stockhausen as well or better than electronic means, but I think we understand each other). The bridge, then, of course. How is the bridge to be built and to what degree is building it going to serve any purpose? The intellectual (sic) praxis of stagnant socialisms demands a total bridge; I write and the reader reads, that is, it’s taken for granted that I write and build the bridge over to a legible level. But what if I’m not legible, old man, what if there’s no reader and therefore no bridge? Because a bridge, even if you have the desire to build one and if all works are bridges to and from something, is not really a bridge until people cross it. A bridge is a man crossing a bridge, by God.

One of the solutions: put a piano on that bridge and then there’ll be a crossing. The other one: build the bridge by all means and leave it there; out of that baby girl suckling in her mother’s arms a woman will come someday who will walk by herself and will cross the bridge, carrying in her arms a baby girl suckling at her breast. And a piano will no longer be needed, there’ll be a bridge all the same, there’ll be people crossing it. But try telling that to all the satisfied engineer builders of bridges and roads and five-year plans.

‘Who called?’ Fernando asked.

‘Oh, that guy, the less said about him the better,’•Patricio opined with perceptible warmth. ‘You’ll see him in the space of ten minutes, it’s Andrés, one of the many Argentines who don’t know what they’re doing in Paris, although he’s got his theory about chosen places and, in any case, he’s won his right to floor space, Susana met him before I did and she can tell you about him, she might even confess to you that she went to bed with him.’

‘On the floor, since you say he’s won the right,’ Susana said. ‘Don’t pay any attention to him, Fernando, he’s a natural-born Turk, every Latin American whose path crossed mine before I met this monster automatically gets on the retrospective jealousy list. It’s good he’s convinced Manuel is his child, because if he wasn’t, the poor kid would be covered with Proustian scar tissue.’

‘Vhat does Andrés do?’ Fernando wanted to know, a little nosey when it came to personal matters.

‘He listens to a wild amount of aleatory music and reads even more, he’s always involved with women, and he’s probably waiting for the moment.’

‘The moment for vhat?’

‘Oh, that . . .’

‘You’re right,’ Susana said. ‘Andrés is like waiting for some moment, but who can say, it’s not ours, in any case.’

‘Vhat’s yours, the revolution and all that?’

‘What a way of asking, this guy must belong to the SIDE (that’s our Argentine intelligence outfit),’ Patricio declared, passing him a mate. ‘Hey, girl, let me have your son, since you’ve just stated that

he’s not retrospective, and translate the news about Nadine for the fellow, this Chilean has got to pick up the local political culture, that way he’ll get a precise idea of why one of these days he’s going to get his ass broken when he begins to take a close look at what’s going on, and there’s a lot going on.’

‘Who’s coming with Andrés?’

‘If you can hold off for a while, Chile boy, you’ll see for yourself, and that’s that, because when they pop by it’s always for more than a spell. What I mean is that Marcos and Lonstein are coming, Argentines too, but from scholarly old Córdoba, if you know about all that, and Ludmilla will probably show up if she survives the Russian tortures they put on at the Vieux-Colombier, three acts of nothing but samovar and knout, not to mention that somewhere along the line the doorbell will ring for the fifth time and the one I told you will drop by, which is fine, because he usually has a bottle of cognac close at hand or at least some chocolate for Manuel, look how the little devil’s eyes are glowing, come to papa, you’re going to be my justification in the eyes of history, m’lad.’

‘Something else I didn’t catch too vell vas vhat you said about the yerba, that somebody stole it somevhere.’

‘Mother of mercy,’ Patricio said, overwhelmed.

‘It’s obvious you’ve never read the adventures of Robin Hood,’ Susana said. ‘Look, Monique is writing a thesis, on the Inca Garcilaso, no less, and she’s covered with freckles. Then she went off with a bunch of Maoists to storm Fauchon, which has gotten to be the Christian Dior for fatbellies, a symbolic act against the bourgeoisie who pay ten francs for a mangy avocado flown in by air. The idea wasn’t new because there’s no such thing as a new idea, in your country they’ve probably pulled off something similar – it was a question of loading the victuals into two or three cars and distributing them among the people in the shantytowns on the north side of Paris. Monique saw a package of yerba and stuck it someplace or other to bring to me, something not foreseen in the operation and somewhat irregular, but,

bearing in mind what happened that night, we must admit it was sublime.’

‘It’s a good introduction to the news item we’re going to translate for your edification,’ Patricio said. ‘You know, something went wrong and the people on the street were ready to lynch the kids, just imagine, they were just people passing by who certainly never went into Fauchon because all they had to do was look in the windows to figure out that it took three months’ wages to buy a dozen apricots and a slice of roast beef, but that’s the way things turn out, Chile boy, the notion of law and order and private property has meaning even for people without a cent to their name. Monique got away in time in one of the cars, but the police caught another girl and even though they obviously couldn’t charge her with robbery since the group had handed out flyers explaining their intentions, the judge sentenced her to thirteen months in the can, mark that, and without – without, what was it?’

‘Without appeal or something like that,’ Susana said. ‘ “I want you to know, young lady, that you are going to spend a year and a month in jail as an example to others who might be thinking about new attacks on things that belong to other people, no matter what reasons are given.” And here’s the piece in the newspaper, because it’s about another girl Monique knows.’

‘Vhat a lot of girls,’ Fernando said, enchanted.

‘Listen: Attack on Meulan town hall. Miss Nadine Ringart paroled. Those are the headlines. Miss Nadine Ringart,

held since March 17 for having taken part in the attack on the employment office of the town hall of Meulan (Yvelines) has just been paroled by Mr Angevin, examining judge of the State Security Court. The young woman, a student of sociology at the Sorbonne, is still accused of violence against the police, voluntary violence with premeditation, violation of residence, and the defacing of a public monument. Period.’

‘Vhat a lot of v’s,’ Fernando said with satisfaction. ‘If you believe that news story, the kid beats Calamity Jane and Agatha Christie, no, I mean that Agata Galiffi you people have in Argentina. Vhile you vere reading, the whole story sounded like a joke; can you imagine seeing it in a newspaper five years ago? And they say it just like that, voluntary violence, violation of residence by a sociology student from the Sorbonne. It’s like a put-on, really.’

‘Nobel Prize winner in theology chops up wife,’ Patricio said. ‘We’d take it just as calmly, like now that they land on the moon twice a week, and what do I care.’

‘Don’t you two start carrying on like my aunt,’ Susana said, rocking Manuel vigorously as he became more and more awake and glowing. ‘There are things I’ll never get used to and that’s why I take the trouble to translate these news items for you, to get the feeling of how much they show and of all the work that’s left for us to do.’

‘All right, that’s exactly what we’ll be talking about with our transandean comrade here, but that’s no reason to get him all worked up at the start, damn it.’

‘Vhat a lot of mystery,’ Fernando said.

‘And vhat a lot of broken asses,’ said Patricio.

It’s probably as a defense, Andrés thought, that Lonstein talks that way, making use of a kind of language that everyone finally ends up understanding, a thing that doesn’t seem to please him too much sometimes. There was a time (we were sharing a cheap room on the Rue de la Tombe-Issoire, it was in the winter of sixty or sixty-one) when he was more explicit, sometimes condescending to say look, any reality that’s worth its salt reaches you through words, leave the rest to apes and geraniums. He would become cynical and reactionary, he said that if this or that weren’t in writing it wouldn’t exist, this newspaper is the world and there isn’t any other, by God, this war exists because the dispatches are here, you write to your old lady because that way you bring her a little life. We didn’t see each other very much afterward, I met Ludmilla, I took some trips and I got tripped up, Francine appeared, in Geneva once I got a postcard from Lonstein and I learned about his work at the medico-legal institute, it was underlined and followed by a swarm of !’s and ?’s, and at the end of one of his sentences: Don’t emplope me too much, haddy; plot me a response, sconce. I sent him a card in return with a view of the squirt on the shores of Lake Leman and made up a message for him with the help of all the signs on an IBM electric; which he must not have liked because four years passed, but that doesn’t matter, what I have to recognize is that this business of words Made in Lonstein was never a game, even though no one could ever tell where it was leading, a defense or an attack, I thought it held Lonstein’s truth in some way, what Lonstein was, small and rather dirty and a Cordovan to the core and self-confessedly a great masturbator and adept of parascientific experiments, fervently Jewish and Latin American, fatally near-sighted, as if anyone could be like Lonstein without

being nearsighted and small, here he is again now, he mooned into my apartment twenty minutes ago without warning, like all South Americans, arriving, of course, with Marcos, who will do anything to avoid saying he’s coming by, fuck their mothers.

These guys have come at a bad time, they’ve caught me right in the middle of a weaning mess, because ever since ten o’clock at night and it’s twelve o’clock now (a very natural time so that Lonstein and Marcos, of course) I’ve been kicking at everything around me, trying to decide once and for all whether it’s the right moment to put the record with Prozession back on or whether I should write a couple of lines answering the Venezuelan poet who sent me a book where everything seems to be underlined or to have been read before, polished words, just like an office master key, patented metaphors and metonymies, such good intentions, such obvious results, bad poetry, purportedly revolutionary, but if only that were all there was to it, Stockhausen or the Venezuelan, the bad part is that matter of bridges, which has my time all tied down, all that trouble with Francine and Ludmilla, but most of all this confusion for which the bridges are to blame that comes along to bother me at a time in the order of things when other people would send it straight to hell, that urge not to give in an inch (why the commonplace of an inch when we are metric decimal system? Traps, traps on every line, the little rabbi is right, reality comes to you through words, so my reality is falser than that of an Asturian priest; plot me a response, sconce), not to give in a single centimeter, which doesn’t fix things up much even though we’re being faithful to the metric system, and at the same time to know that I am commingling, contributing, compensating, commiserating, but in no way consenting, and that’s where the confusion starts and, why not say so, fear, this has never happened to me, things would come to me and I would manipulate them and turn them around and boomerang them without coming out of my shell until one of those times precisely when I could feel myself more enshelled than ever, it’s not only confusion that fills your ashtray with bitter butts, it’s everything, loves, dreams, the taste of coffee,

the subway, paintings, and political meetings start to twist, to mingle, they become all tangled up among themselves, Ludmilla’s little ass is the speech by Pierre Gonnard at the Mutualité, unless the speech is that little ass that I don’t wish to recall now, and, to top it off, Lonstein and Marcos at this moment, fuck it all.

It’s something like this, the poor beasty comes out into the ring and stands very still, snorting. He just doesn’t understand, here he’d been in the dark, given his feed, everything was going along fine with the aid of trucks, shaking, and habit, everything had started to be a smell, a distant sound, a total absence of the past, and all of a sudden through an alley with shouts and poles, a huge circle filled with colors and paso dobles, a sinking sun in his eyes, and then boff the hoof writing the cipher of confusion in the sand. ¿Qué coño? thinks the beasty, who is Spanish naturally, since the Japanese haven’t gone into the bullfight business yet the way they’ve done with French oysters, what the hell is this all about? I’d like to ask Lonstein or Marcos about it, for example, now that they’ve come by (not to mention Ludmilla, who will pop by as soon as she finishes her role at the Vieux-Colombier), but what am I going to ask them and why, since the confusion is more than can be put in a question because it’s already obvious that the business about Stockhausen and Ludmilla’s little ass and the Venezuelan bard are only small pieces, just a few tessellas in the mosaic, and there it is, what right do I have to use the word tessella, which probably won’t say a thing to a lot of people, and why in hell not use it since it tells me all that’s necessary and, besides, the context helps and now everybody knows what a tessella is, but the problem isn’t that, but, rather, the awareness that it is a problem, an awareness I’d never had before and which is slowly shoving me into life and into language like Lonstein and Marcos into my place, late and without warning, half on the bias, it’s obvious that I’m emploped too deep, haddy. Because, to top it off, Lonstein and Marcos have started talking now and that’s precisely the other tip of the problem, a kind of wager against the impossible, but they just go on, and try stopping them. Just in case, I’m going to call Patricio, if they get

to be a drag I’ll slowly set them adrift and listen to Prozession again, it would seem that the choice has been made and the Venezuelan poet has lost, poor lad.

The topic is the morgue, in plain talk the medico-legal institute, drowned people, Lonstein has let himself go tonight, Lonstein, who never talks about his work, but Marcos, behind his cigarette, is slowly going back and forth in Ludmilla’s rocker, he runs his hand through his curly locks from time to time, throws back his curls and releases the smoke slowly through his nose. Andrés hasn’t asked Marcos a thing, as if slipping into his apartment in the middle of the night was the most natural thing in the world, and Marcos almost enjoys that somewhat aloof procedure Andrés is taking, waits a while longer, and Lonstein going on about suicides and schedules, completely off the track in spite of the instructions received along the route of eight Métro stations and two grappas in a café. Even Andrés seems to sense that something’s out of gear, he listens to Lonstein but he’s looking at Marcos as if asking him what the hell and for how long, damn it.

‘Turn off your hose, rabbi junior grade,’ orders Marcos, who is rather amused inside. ‘Save your Edgar Allan Poe for the people when we’re at Patricio’s, the women will listen to you with their souls dangling on a string, you know what necrophiliacs they are. The idea, my good man, was to use our visit to talk about things that are a bit more alive, plugging you and your little Polack girl into a cram course in Latin American informatics, something you seem a little far-removed from. This talmudic beast was told to break the ice, but you got ahead of us as soon as the gong sounded and all these fancy-dress preliminaries annoy me.’

‘Out with it, then,’ I said in resignation.

‘Well, this is what it’s all about, more or less.’

I finally came to understand that one of the most important reasons behind Marcos’s visit was to use my telephone, because he didn’t trust his own those days. I should have asked him why, but if I didn’t ask him, Marcos would avoid having to tell a lie and, besides, I didn’t feel too keen about getting involved in Marcos’s thing, at least when I wasn’t at Patricio’s, where politics and direct and indirect action were practically the only reason people opened their mouths. Marcos knew me, he wasn’t bothered by my nonparticipation; with Lonstein and me he enjoyed a relationship like that of old schoolmates (we weren’t) and no other contact was needed. He let himself go with Ludmilla, talking about everything going on at the moment, all the binds he and Patricio were mixed up in; sometimes he’d look at me from behind the smoke of his cigarette as if wanting to know where I stood, why I wasn’t taking that little step forward or running off a little to the side in order to go into orbit. And so, while he was phoning an endless series of male and female characters, in French and Spanish and sometimes in a mysterious ginzoid gibberish (the one on the other end was named Pascale and was answering from Genoa, my phone bill for that three-month period was going to be hairy, mustn’t let him leave without settling up), Lonstein and I were chatting, drinking white wine and reminiscing about the good, cheap semillón wine in waterfront bars. Poor Lonstein had got a raise that week and he was mournful, thinking that everything has its counterweight and that they were going to break his back with work; his misfortune had made him strangely talkative, Marcos had to keep hushing him up so he could hear somebody who must have been in a phone booth somewhere in Budapest or Uganda, then the little rabbi would lower his voice a bit and on with the drownings,

the night schedule at the morgue, asphyxiated people, the ones who jump out windows, the ones burned, girls raped with previous (or simultaneous) strangulation, boys idem, suicides by poison, a bullet in the head, illuminating gas, barbiturates, razors, accident victims (cars, trains, military maneuvers, fireworks, construction scaffolds) and last but yes least, the beggars dead of cold or vinous intoxication as they try to defend themselves against the first with the help of the second on top of some subway grating always warmer than the sidewalk where the busy and honest petit bourgeois and working-class population of the capital walks by without pausing. But Lonstein doesn’t give those statistics with such enumerative precision, for as far as his work is concerned, his versions are mainly exercises in language, making it difficult to know what belongs to Caesar and what belongs to the morgue, tonight Lonstein is outdoing himself in elocution and in his Cordovan accent he talks about such things as apwals and shell-balls, which, from their early contexts, I deduce are the occupants of forensic tables, and he whimpers on from there that he has a hell of a lot of work when he gets to the icebox between eight and nine o’clock and half a dozen apwals are already waiting for him to undior them, unchanel them, peep off their things little by little, getting them slowly used to the marble, to the horizontal position where ankles, gluteals, shoulder blades, and neck will receive, to a more or less equal degree, the influence of the law of gravity for lack of any better one, what can you do.

‘Pascale, puoi dire a quello là che è un fesa,’ Marcos is saying. ‘Have him send me the melons directly to Little Red Riding Hood’s.’

The key to those things, Andrés thinks, the melons must be pamphlets or pistols, Little Red Riding Hood must be Gómez, who shaves every two hours.

‘Then the laving reannoys me,’ Lonstein is explaining, ‘if you’re lucky put the case that start the passing in review, a femme between fourteen and fifteen, all talcum powder and the face of a Luna Park Saturday night except that at respiration level there’s a black-andblue ruff and on the skirt a wild double ketchup concentrated

map, then I have to go about removing her dreamcovers, cutting elastics and lowering sticky tergals until I can see every foliole, every ficciore, the operation, life’s impairments. Sometimes gimpy Tergov helps me, but if it’s a cutey I send him to work at the other table, I prefer washing her by myself, alone, an apwal like in her mama’s time, you understand, a little sponge here, a little sponge there, I leave them for you better than on the day they received their first, Tergov only slops a bucket of water over them and kind of from a distance rearranges their hair and lays their arms and underpinning straight, I, on the other hand, will turn them over, if they’re worth anything, not just to look at them, I don’t want you to think, but, naturally, what do you think Leonardo did and look how they respect him, sometimes it’s hard to believe they’ve got no more urge for a little humping, going around with their whole life in their assholes, it’s like you were giving them a little help, even though, of course, you end up sad, hell, they don’t cooperate. The one last night at eleven o’clock, for exemplum, they brought her in while I was off to Marthe’s to have me a rum, I come back and, what can I say, another job on table six, I don’t know why they always put the cutest ones on table six, I lower the pink, I cut the black, and I lift the rayon, it was even hard for me to take, Tergov had the card from the fuzz, gas, you could tell that already by her nosey and her nails, but what do you know, still warm, I swear, although it could have been from the meat wagon now that they’ve bought some that look like Swiss chalets, there I was; she couldn’t have been more than eighteen, her cute little hair bicolored and her knees softer than I’d ever seen; there was a lot to do for her because gas, I don’t know whether you’re aware or not, but I’ll tell you about that later; well, half an hour with strong detergency, a general ablution, the phase of glove on wardsback, the froth, I hope you won’t think that I’ll end up as a necrophile.’

‘Let’s just say you like what you like,’ says Marcos, who is listening as if from a distance as he dials another number and that makes seven.

‘When they’re boizy or flonde, when they still look like sundials, then they do awaken the florence-galen-night in me, after all it is a good way of getting up Death’s ass, not let them be strapstepped up against the ropes, and that’s why you have to be careful, my boy, denoose them and froth them, and that way, when you’ve hundled them well, they’re the same again, just like the ones prepaired at home or at the Mayo clinic with the help of the blessed woman and the galenizers, because in the end there’s no reason why my apwals, young as they are at times, should run handicapped by the grelle, you understand, I mean bad luck, if I can terminologize discepoliarily.’

‘Oh, brother!’ Marcos says, annoyed, hard to tell whether because of Lonstein or because the line is busy.

‘Let him go on,’ I tell him, ‘it’s been years since he’s turned himself loose like this, when a monster takes off you have to gallop alongside, let’s be Christian about it.’

‘You’re a mother,’ Lonstein says, visibly content. ‘People are like those classic torturers who ended up as neurotics because all they had was their no-less-classic daughter to whom they could recount every detail of torturocomy and leadsqueals; don’t you realize that in Marthe’s bistro I didn’t go around declining my gig as my co-pains say, and that condemns me to silence, apart from the fact that since I’m a celibate, chaste like Onan and master of my bait, there’s no exutory left for me but soliloquy, except for the privybook where from time to time I defescrape a turdscript or two. The worst part, as I was explaining to you, is that now that they’ve doubled my work these days under the pretext of paying me four times as much, I agreed, as an incurable outpopper and, besides the inst I’ve got the hosp. All Hindus, there’d been a wave of Czechs, but now they’re all Hindus, Made in Madras, word of honor.’

‘Hindus, shit,’ Marcos says.

‘Kidnapped right off the funeral pyre,’ Lonstein insists, ‘and hermeneutically canned in numbered containers with an indescription of age and sex, who the hell knows how they’ve set the

racket up, but one of these days the people in Benares who sell wood for cremation are going to raise such hell that it will put to shame the blackass Calcutta hole we studied about in the Bolívar National School, Province of Buenos Aires, Jesus, the things dumb old Cancio taught us, he was a wild prof we had, oh nostalmia, oh exuborium!’

‘You mean they import Hindu corpses for dissection?’ asks Marcos, who’s starting to be hooked. ‘Get out of here with your damned stories, take your drivel somewhere else.’

‘I sacre to you by what’s most sworn,’ Lonstein says. ‘Gimpy Tergov and I have the job of opening the containers and preparing the merchandise for the night of the long knives, which is on Thursdays and Mondays. Look, at this point you get a negascientific element of the many that the gimp and I garbage away because the profs don’t want to find the raw material in anything but a state of integral ballnakedness.’

From his pocket he takes a paper flower with a wire stem and flips it to Marcos, who leaps from his chair and cuts him with a son-of-a-bitch. I start thinking about herding them slowly toward the door, because it’s not right to keep Patricio and Susana waiting until one o’clock in the morning and it’s five after one already.