Angela Carter was born in 1940. She lived in Japan, the United States and Australia. Her first novel, Shadow Dance, was published in 1965. Her next book, The Magic Toyshop, won the John Llewllyn Rhys Prize and the next, Several Perceptions, the Somerset Maugham Award. She died in February 1992.

ANGELA CARTER

Fireworks

Black Venus

American Ghosts and Old World Wonders

Burning Your Boats: Collected Short Stories

The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories

The Virago Book of Fairy Tales (editor)

The Second Virago Book of Fairy Tales (editor)

Wayward Girls and Wicked Women (editor)

Shadow Dance

The Magic Toyshop

Several Perceptions

Heroes and Villains

Love

The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman

The Passion of New Eve

Wise Children

The Sadeian Woman: An Exercise in Cultural History

Nothing Sacred: Selected Writings

Expletives Deleted

Shaking a Leg: Collected Writings

Come Unto These Yellow Sands: Four Radio Plays

The Curious Room: Collected Dramatic Works

w ITH AN INTROD u CTION BY Sarah Waters

Vintage Classics is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies

Vintage, Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London Sw11 7Bw

penguin.co.uk/vintage-classics global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright © Angela Carter 1984

Introduction copyright © Sarah Waters 2006

The moral right of the author has been asserted

This edition published in Vintage Classics in 2025 First published in Great Britain by Chatto & Windus in 1984

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781529955606

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

My first encounter with the lush, extravagant universe of Angela Carter’s fiction came in 1984, when I was just eighteen. This was the year that Carter collaborated with Neil Jordan to produce the film The Company Wolves. Quite by chance, I caught a radio programme promoting the film, and discussing Carter’s collection of rewritten fairy tales, The Bloody Chamber, on which it was based. I’d had a taste for the Gothic since childhood. The idea of a book which seemed to mix Perrault and Grimm with Hammer Horror impressed me enormously. Carter’s name stuck in my mind and, on a trip to Cardiff soon after, I went into a bookshop and sought The Bloody Chamber out.

I was a bookish teenager and relatively well-read, but Carter’s writing was unlike anything I’d ever come across before: vivid, theatrical, full of dazzlingly rococo narrative swoops and a startling sexual bluntness. A few years later, studying The Bloody Chamber for a literature MA, I would appreciate more than ever the sophistications of Carter’s project, her engagement with the founding myths of Western culture, and with Freud and Lacan. But in the meantime, I simply read every bit of her writing I could lay my hands on. The Passion of New Eve and Heroes and Villains I discovered to be baroque apocalyptic fables, stories of sex-change, sorcery, the epic struggle between civilisation and chaos. The Magic Toyshop I read as a Gothic story of adolescent awakening, of pleasure and fear. The Sadeian Woman,a piece of cultural criticism, daringly recast the Marquis de Sade as a clear-sighted anal yst of sexual relati ons, the feminist’s ‘unconscious ally’.

Nights at the Circus was published in the autumn of 1984, as I was starting life as an English student, too poor to afford a hardback. I bought the novel when it came out in paperback the following year and begged the university bookshop to give me the poster that had been sent out as part of the publicity campaign; and I stuck it to my college bedroom wall, as I might have pinned up other iconic ’80s images – the film poster for Betty Blue, or stickers saying ‘Coal Not Dole.’

I had to wait until 1991 for Carter’s next novel, the rambunctious Wise Children; this time, a girlfriend bought me the hardback as a birthday present. I had no idea that this would be Carter’s last work. I did not know that she was already becoming ill. This was years before I ever thought of writing myself, and the literary world was a closed and very distant one. I was familiar with a much-reproduced image of her, which showed an appealing-looking, handsome woman with strikingly high cheekbones and white hair, but I had never seen her speak or read from her work. Then, on a Sunday evening in the February of 1992, a friend rang me up to say that he had just heard on the radio that Angela Carter had died of lung cancer. We were both floored by the news –both, absurdly, as upset as if we’d known Carter personally; and both, with the sorrow of passionate readers, devastated at the loss of such a glorious literary talent.

Our reaction was, I suspect, far from unique. Carter’s literary reputation had been relatively slow to build; there had been a surge of popular interest in her work, at exactly the time I’d first heard of her, as a result of the release of Jordan’s film; but her audience, after that, remained a fiercely devoted one. And her writing had a particular resonance, I think, for women readers. Her theatrical, fabular style has much in common with that of the other great magic realists, Salman Rushdie and Gabriel Garcia Marquez; but she wrote, always, with a distinctly feminist agenda, determined to debunk cultural fantasies around sexuality, gender and class. She helped stimulate an excitement about feminist writing and feminist publishing (she was hugely supportive, for vi

viii

Nights at the Circus is her masterpiece; it’s also the most engaging and accessible of her fictions. Her earliest novels tend towards the stylised; Nights, by contrast, is a sprawling, garrulous book, a picaresque story of Rabelaisian proportions, with a suitably larger-than-life heroine: Fevvers, the winged Victorian ‘Cockney Venus’, six feet two in her stockings, with a voice like clanging dustbin lids and a face as ‘broad and oval as a meat dish’. Fevvers’s extraordinary lifestory – given in the form of an interview to a sceptical American journalist, Jack Walser, backstage at the Alhambra Music Hall – makes up the novel’s substantial Part One. After that, still in pursuit of his story, Walser signs up alongside Fevvers as a clown, and Parts Two and Three transport us, unexpectedly, to Imperi al Russia; first to the barely controlled mayhem of the St Petersburg Circus and then to the dizzying white wastes of Siberia. As the landscape grows more extreme, so Carter pushes at the limits of the novel form itself. The cosy realist start expands, via fantasy and allegory, to open up a space for radical change. By the end of the book, personalities will have been reformed, social and gender dynamics rewritten, by – a wonderful phrase, which beautifully sums up Carter’s style and literary ethos – ‘the radiant shadow of the implausible’.

For Carter was, among many things, a fabulous storyteller, a professional liar, always revelling in narrative and its rude, primal pull. Nights at the Circus is full of stories, its basic structure regularly opening out to offer us the potted biographies of minor characters. There are Ma Nelson’s vii

ix example, of the founding of the women’s publishing house Virago Press, in 1979), and many of her literary preoccupations – the challenging of the canon, the rewriting of fairy tale and myth, the imagining of female utopias and dystopias – lie at the heart of much feminist writing and thought from the 1970s and ’80s. But few other writers, female or male, had her imagination, her literary audacity, her confidence with language and idea. Few had her power to unsettle as well as to inspire and console.

The novel treads a similarly agile path between realism and fantasy. Its historical setting, for example, is a very specific and meaningful one – the action takes place at the ‘fag-end’ of the 1890s, and Fevvers is utterly a woman of her time, a woman who’s been painted by Lautrec, had supper with Willy and Colette, troubled the psychoanalysts of Vienna, and been courted by the Prince of Wales. The outrageous name-dropping becomes more sly and more exuberant as the novel proceeds. Carter’s pen trips with wonderful breeziness through the Western literary canon, offering us echoes of Goethe, Shakespeare, Poe, Swift, Baudelaire, Mozart and Blake; but giving nods, too, to Yeats, Laurel and Hardy, Foucault, and –‘They’re a girl’s best friend,’ twinkles Fevvers at one point, displaying her diamond earrings – Anita Loos. As these flagrant anachronisms hint – and as Carter makes explicit once we reach the ‘Sleeping Beauty of a city’ that is fin de siècle St Petersburg, soon to be awakened by the ‘bloody kiss’ of revolution – Nights at the Circus does not belong to ‘authentic history’. It offers, instead, a kind of fantasy history, weaving its stories in and across the gaps, silences and pregnant shadows of recorded fact.

It’s a tr ib ute to Carter’s skill as a novelist th at her characters can inhabit this gloriously artificial universe and viii

x prostitutes, for example, who first discover Fevvers, newly hatched and abandoned, in a basket on the doorstep of their Whitechapel brothel. There are the inhabitants of the Museum of Women Monsters – Fanny Four-Eyes, the Wiltshire Wonder, and others – with whom Fevvers briefly throws in her fortunes once the brothel is disbanded. There are the artistes of the Imperial Circus: Mignon, theApe-Man’s abused missus; the tiger-taming Abyssinian Princess; and Buffo the Clown, who loses his wits mid-performance and is carted off to an asylum – much to the delight of the unsuspecting crowd, for whom it’s all part of the craziness of th e ring. These characters’ stories erupt like fantastic bl ossoms out of the already gaudy fo liage of Carter’s narrative, pushing it in wild, surprising directions but never throwing it off balance or weighing it down.

yet remain so emotionally compelling and physically convincing. Even Fevvers’s feathers convince us. Carter clearly gave them an awful lot of thought – ‘Really,’ she once said, in interview, ‘how very, very inconvenient it would be for a person to have real wings, just how really difficult’ – and I’ve always been tickled by the attention she gives to Fevvers’s aerodynamics, the detail into which Fevvers goes when explaining to Walser her awesome but inconvenient physique:

My legs don’t tally with the upper part of my body from the point of view of pure aesthetics, d’you see. Were I to be the true copy of Venus, one built on my scale ought to hav e legs like tree- trunk s, si r; these fl imsy little underpinnings of mine have more than once buckled up under the top-heavy distribution of weight upon my torso, have let me down with a bump and left me sprawling. I’m not tip-top where walking is concerned, sir, more tip-up.

Fevvers is a wonderfully fleshly creation, a creature of sweats and appetites, of belches and farts. Her predicament – like that of many charismatic women (like Wedekind’s Lulu, for example, about whom Carter would write a stage play in 1987) – is that she is continually preyed upon by people seeking to turn her into a commodity or a symbol. She narrowly escapes being ritually sacrificed by the sinister Mr Rosencreutz, who sees her as ‘Flora; Azrael; Venus Pandemos!’. She is almost turned into a literal ‘bird in a gilded cage’ by a Russian Grand Duke. Just as Walser, ‘unfinished’ at the novel’s start, must be remade, reformed, via amnesia and cultural displacement, so Fevvers has to learn how to tell her own story, on her own terms: to become ‘No Venus, or Helen, or Angel of the Apocalypse, not Izrael or Isfahel’, but the agent of her own imagination and her own desire. For only then will she become a symbol really worth celebrating – a symbol of the new century which, significantly, is just

xi

breaking at the novel’s close, a century in which (with a bit of luck) ‘all the women will have wings’.

Carter was committed to telling tales of transformation throughout her career; in The Bloody Chamber, women are transformed into beasts, beasts are changed into men, in allegories of power and desire. Like all her fictions, Nights at the Circus has its share of villians and victims, female and male, but the narrative ultimately celebrates liberation, the casting off of myth and mind forg’d manacles, the discovery of voice, empathy, conscience, the making of a ‘new kind of music’. The novel ends with Fevvers’s laughter, with an affirmation of life. And Carter’s very prose is something to smile at, teeming as it does with memorable images, metaphors and similes. A drawing-room, for example, is ‘snug as a groin’. A woman ‘crackle[s] quietly with her own static’. A sky is ‘tinted the lavender of half-mourning’, a violet is ‘the colour of tired eyelids’, a tiger moves ‘like orange quicksilver, or a rarer liquid metal, a quickgold’. Carter’s writing, not just in this novel but throughout her work, is a celebration of words – a celebration of language and all the marvellous things that language can be made to do.

It’s this combination of lushness and tremendous optimism, I think, which made Nights at the Circus so memorable for so many readers in Margaret Thatcher’s Britain in the 1980s; and it’s something which renders the novel inspiring today, in a different political climate but at a time when much British fiction seems to affect an affectless style, and to be interested in themes of failure, decay, and disappointment. Like all thoughtful novelists, Carter engaged very explicitly with the issues of her day. Her account of the Imperial Circus was written in a period when St Petersburg had been reborn twice, as Petrograd and Leningrad, but before its original name had been restored to it; and in a world in which Nike – the Winged Victory whom Fevvers impersonates a t the Wh itecha pel brothel – wa s still a relatively innocent motif. One can’t help but wonder what Carter would have made of post-Communist politics, x

xii

globalisation, New Labour, the invasion of Iraq, and –because one of her strengths, I think, was her promiscuous plundering of popular culture as well as the canon – it’s impossible not to regret the rich and irreverent fictions she might have woven out of reality TV, the cult of celebrity, cosmetic surgery, and ASBOs. She was one of the great late twentieth-century British writers, producing novels, short stories, journalism and plays that spoke to a shared cultural climate, but in a style that was entirely her own. She was also enormously influential. Rereading Nights at the Circus for this reissue, in fact, I could see, in a rich, original form, many of the themes and preoccupations that have surfaced in my own work. I could never have written the novels that I have without having read the fictions of Angela Carter first. I’m still sorry that I shall never get to meet her, and thank her.

Sarah Waters,

2006

‘Lor’ love you, sir!’ Fevvers sang out in a voice that clanged like dustbin lids. ‘As to my place of birth, why, I first saw light of day right here in smoky old London, didn’t I! Not billed the “Cockney Venus”, for nothing, sir, though they could just as well ’ave called me “Helen of the High Wire”, due to the unusual circumstances in which I come ashore – for I never docked via what you might call the normal channels, sir, oh, dear me, no; but, just like Helen of Troy, was hatched. ‘Hatched out of a bloody great egg while Bow Bells rang, as ever is!’

The blonde guffawed uproariously, slapped the marbly thigh on which her wrap fell open and flashed a pair of vast, blue, indecorous eyes at the young reporter with his open notebook and his poised pencil, as if to dare him: ‘Believe it or not!’ Then she spun round on her swivelling dressing-stool – it was a plush-topped, backless piano stool, lifted from the rehearsal room – and confronted herself with a grin in the mirror as she ripped six inches of false lash from her left eyelid with an incisive gesture and a small, explosive, rasping sound.

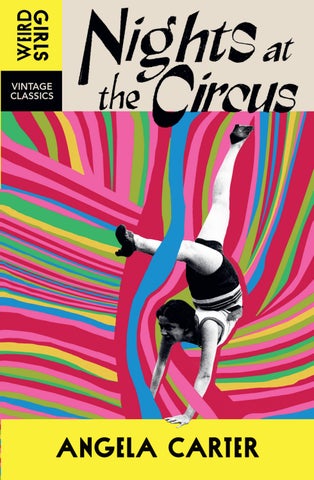

Fevvers, the most famous aerialiste of the day; her slogan, ‘Is she fact or is she fiction?’ And she didn’t let you forget it for a minute; this query, in the French language, in foot-high letters, blazed forth from a wall-size poster, souvenir of her Parisian triumphs, dominating her London dressing-room. Something hectic, something fittingly impetuous and dashing about that poster, the preposterous depiction of a young woman shooting up like a rocket, whee! in a burst of agitated sawdust towards an unseen trapeze somewhere above in the 3

wooden heavens of the Cirque d’Hiver. The artist had chosen to depict her ascent from behind – bums aloft, you might say; up she goes, in a steatopygous perspective, shaking out about her those tremendous red and purple pinions, pinions large enough, powerful enough to bear up such a big girl as she. And she was a big girl.

Evidently this Helen took after her putative father, the swan, around the shoulder parts.

But these notorious and much-debated wings, the source of her fame, were stowed away for the night under the soiled quilting of her baby-blue satin dressing-gown, where they made an uncomfortable-looking pair of bulges, shuddering the surface of the taut fabric from time to time as if desirous of breaking loose. (‘How does she do that?’ pondered the reporter.)

‘In Paris, they called me l’Ange Anglaise, the English Angel, “not English but an angel”, as the old saint said,’ she’d told him, jerking her head at that favourite poster which, she’d remarked off-handedly, had been scrawled on the stone by ‘some Frog dwarf who asked me to piddle on his thingy before he’d get his crayons so much as out sparing your blushes’. Then – ‘a touch of sham?’ – she’d popped the cork of a chilled magnum of champagne between her teeth. A hissing flute of bubbly stood beside her own elbow on the dressing-table, the still-crepitating bottle lodged negligently in the toilet jug, packed in ice that must have come from a fishmonger’s for a shiny scale or two stayed trapped within the chunks. And this twice-used ice must surely be the source of the marine aroma – something fishy about the Cockney Venus – that underlay the hot, solid composite of perfume, sweat, greasepaint and raw, leaking gas that made you feel you breathed the air in Fevvers’ dressing-room in lumps.

One lash off, one lash on, Fevvers leaned back a little to scan the asymmetric splendour reflected in her mirror with impersonal gratification.

‘And now,’ she said, ‘after my conquests on the continent’ (which she pronounced, ‘congtinong’) ‘here’s the prodigal

daughter home again to London, my lovely London that I love so much. London – as dear old Dan Leno calls it, “a little village on the Thames of which the principal industries are the music hall and the confidence trick”.’

She tipped the young reporter a huge wink in the ambiguity of the mirror and briskly stripped the other set of false eyelashes.

Her native city welcomed her home with such delirium that the Illustrated London News dubbed the phenomenon, ‘Fevvermania’. Everywhere you saw her picture; the shops were crammed with ‘Fevvers’ garters, stockings, fans, cigars, shaving soap . . . She even lent it to a brand of baking powder; if you added a spoonful of the stuff, up in the air went your sponge cake, just as she did. Heroine of the hour, object of learned discussion and profane surmise, this Helen launched a thousand quips, mostly on the lewd side. (‘Have you heard the one about how Fevvers got it up for the travelling salesman . . .’) Her name was on the lips of all, from duchess to costermonger: ‘Have you seen Fevvers?’ And then: ‘How does she do it?’ And then: ‘Do you think she’s real?’

The young reporter wanted to keep his wits about him so he juggled with glass, notebook and pencil, surreptitiously looking for a place to stow the glass where she could not keep filling it – perhaps on that black iron mantelpiece whose brutal corner, jutting out over his perch on the horsehair sofa, promised to brain him if he made a sudden movement. His quarry had him effectively trapped. His attempts to get rid of the damn’ glass only succeeded in dislodging a noisy torrent of concealed billets doux, bringing with them from the mantelpiece a writhing snakes’ nest of silk stockings, green, yellow, pink, scarlet, black, that introduced a powerful note of stale feet, final ingredient in the highly personal aroma, ‘essence of Fevvers’, that clogged the room. When she got round to it, she might well bottle the smell, and sell it. She never missed a chance. Fevvers ignored his discomfiture. Perhaps the stockings had descended in order to make common cause with the other elaborately intimate garments,

wormy with ribbons, carious with lace, redolent of use, that she hurled round the room apparently at random during the course of the many dressings and undressings which her profession demanded. A large pair of frilly drawers, evidently fallen where they had light-heartedly been tossed, draped some object, clock or marble bust or funerary urn, anything was possible since it was obscured completely. A redoubtable corset of the kind called an Iron Maiden poked out of the empty coalscuttle like the pink husk of a giant prawn emerging from its den, trailing long laces like several sets of legs. The room, in all, was a mistresspiece of exquisitely feminine squalor, sufficient, in its homely way, to intimidate a young man who had led a less sheltered life than this one. His name was Jack Walser. Himself, he hailed from California, from the other side of a world all of whose four corners he had knocked about for most of his five-and-twenty summers – a picaresque career which rubbed off his own rough edges; now he boasts the smoothest of manners and you would see in his appearance nothing of the scapegrace urchin who, long ago, stowed away on a steamer bound from ’Frisco to Shanghai. In the course of his adventuring, he discovered in himself a talent with words, and an even greater aptitude for finding himself in the right place at the right time. So he stumbled upon his profession, and, at this time in his life, he filed copy to a New York newspaper for a living, so he could travel wherever he pleased whilst retaining the privileged irresponsibility of the journalist, the professional necessity to see all and believe nothing which cheerfully combined, in Walser’s personality, with a characteristically American generosity towards the brazen lie. His avocation suited him right down to the ground on which he took good care to keep his feet. Call him Ishmael; but Ishmael with an expense account, and, besides, a thatch of unruly flaxen hair, a ruddy, pleasant, square-jawed face and eyes the cool grey of scepticism.

Yet there remained something a little unfinished about him, still. He was like a handsome house that has been let,

furnished. There were scarcely any of those little, what you might call personal touches to his personality, as if his habit of suspending belief extended even unto his own being. I say he had a propensity for ‘finding himself in the right place at the right time’; yet it was almost as if he himself were an objet trouvé, for, subjectively, himself he never found, since it was not his self which he sought.

He would have called himself a ‘man of action’. He subjected his life to a series of cataclysmic shocks because he loved to hear his bones rattle. That was how he knew he was alive.

So Walser survived the plague in Setzuan, the assegai in Africa, a sharp dose of buggery in a bedouin tent beside the Damascus road and much more, yet none of this had altered to any great degree the invisible child inside the man, who indeed remained the same dauntless lad who used to haunt Fisherman’s Wharf hungrily eyeing the tangled sails upon the water until at last he, too, went off with the tide towards an endless promise. Walser had not experienced his experience as experience; sandpaper his outsides as experience might, his inwardness had been left untouched. In all his young life, he had not felt so much as one single quiver of introspection. If he was afraid of nothing, it was not because he was brave; like the boy in the fairy story who does not know how to shiver, Walser did not know how to be afraid. So his habitual disengagement was involuntary; it was not the result of judgment, since judgment involves the positives and negatives of belief.

He was a kaleidoscope equipped with consciousness. That was why he was a good reporter. And yet the kaleidoscope was growing a little weary with all the spinning; war and disaster had not quite succeeded in fulfilling that promise which the future once seemed to hold, and, for the moment, still shaky from a recent tussle with yellow fever, he was taking it a little easy, concentrating on those ‘human interest’ angles that, hitherto, had eluded him.

Since he was a good reporter, he was necessarily a connoisseur of the tall tale. So now he was in London he went

to talk to Fevvers, for a series of interviews tentatively entitled: ‘Great Humbugs of the World’.

Free and easy as his American manners were, they met their match in those of the aerialiste, who now shifted from one buttock to the other and – ‘better out than in, sir’ – let a ripping fart ring round the room. She peered across her shoulder, again, to see how he took that. Under the screen of her bonhomerie – bonnefemmerie? – he noted she was wary. He cracked her a white grin. He relished this commission!

On that European tour of hers, Parisians shot themselves in droves for her sake; not just Lautrec but all the postimpressionists vied to paint her; Willy gave her supper and she gave Colette some good advice. Alfred Jarry proposed marriage. When she arrived at the railway station in Cologne, a cheering bevy of students unhitched her horses and pulled her carriage to the hotel themselves. In Berlin, her photograph was displayed everywhere in the newsagents’ windows next to that of the Kaiser. In Vienna, she deformed the dreams of that entire generation who would immediately commit themselves wholeheartedly to psychoanalysis. Everywhere she went, rivers parted for her, wars were threatened, suns eclipsed, showers of frogs and footwear were reported in the press and the King of Portugal gave her a skipping rope of egg-shaped pearls, which she banked.

Now all London lies beneath her flying feet; and, the very morning of this self-same October’s day, in this very dressingroom, here, in the Alhambra Music Hall, among her dirty underwear, has she not signed a six-figure contract for a Grand Imperial Tour, to Russia and then Japan, during which she will astonish a brace of emperors? And, from Yokohama, she will then ship to Seattle, for the start of a Grand Democratic Tour of the United States of America.

All across the Union, audiences clamour for her arrival, which will coincide with that of the new century.

For we are at the fag-end, the smouldering cigar-butt, of a nineteenth century which is just about to be ground out in the ashtray of history. It is the final, waning, season of the year of

Our Lord, eighteen hundred and ninety-nine. And Fevvers has all the éclat of a new era about to take off.

Walser is here, ostensibly, to ‘puff’ her; and, if it is humanly possible, to explode her, either as well as, or instead of. Though do not think the revelation she is a hoax will finish her on the halls; far from it. If she isn’t suspect, where’s the controversy? What’s the news?

‘Ready for another snifter?’ She pulled the dripping bottle from the scaly ice.

At close quarters, it must be said that she looked more like a dray mare than an angel. At six feet two in her stockings, she would have to give Walser a couple of inches in order to match him and, though they said she was ‘divinely tall’, there was, off-stage, not much of the divine about her unless there were gin palaces in heaven where she might preside behind the bar. Her face, broad and oval as a meat dish, had been thrown on a common wheel out of coarse clay; nothing subtle about her appeal, which was just as well if she were to function as the democratically elected divinity of the imminent century of the Common Man.

She invitingly shook the bottle until it ejaculated afresh. ‘Put hairs on your chest!’ Walser, smiling, covered his glass up with his hand. ‘I’ve hairs on my chest already, ma’am.’

She chuckled with appreciation and topped herself up with such a lavish hand that foam spilled into her pot of dry rouge, there to hiss and splutter in a bloody froth. It was impossible to imagine any gesture of hers that did not have that kind of grand, vulgar, careless generosity about it; there was enough of her to go round, and some to spare. You did not think of calculation when you saw her, so finely judged was her performance. You’d never think she dreamed, at nights, of bank accounts, or that, to her, the music of the spheres was the jingling of cash registers. Even Walser did not guess that.

‘About your name . . .’ Walser hinted, pencil at the ready. She fortified herself with a gulp of champagne.

‘When I was a baby, you could have distinguished me in a crowd of foundlings only by just this little bit of down, of

yellow fluff, on my back, on top of both my shoulder blades. Just like the fluff on a chick, it was. And she who found me on the steps at Wapping, me in the laundry basket in which persons unknown left me, a little babe most lovingly packed up in new straw sweetly sleeping among a litter of broken eggshells, she who stumbled over this poor, abandoned creature clasped me at that moment in her arms out of the abundant goodness of her heart and took me in.

‘Where, indoors, unpacking me, unwrapping my shawl, witnessing the sleepy, milky, silky fledgling, all the girls said: “Looks like the little thing’s going to sprout Fevvers!” Ain’t that so, Lizzie,’ she appealed to her dresser.

Hitherto, this woman had taken no part in the interview but stood stiffly beside the mirror holding a glass of wine like a weapon, eyeing Jack Walser as scrupulously as if she were attempting to assess to the last farthing just how much money he had in his wallet. Now Lizzie chimed in, in a dark brown voice and a curious accent, unfamiliar to Walser, that was, had he known it, that of London-born Italians, with its double-barrelled diphthongs and glottal stops.

‘That is so, indeed, sir, for wasn’t I myself the one that found her? “Fevvers”, we named her, and so she will be till the end of the chapter, though when we took her down to Clement Dane’s to have her christened, the vicar said he’d never heard of such a name as Fevvers, so Sophie suffices for her legal handle.

‘Let’s get your make-up off, love.’

Lizzie was a tiny, wizened, gnome-like apparition who might have been any age between thirty and fifty; snapping, black eyes, sallow skin, an incipient moustache on the upper lip and a close-cropped frizzle of tri-coloured hair – bright grey at the roots, stark grey in between, burnt with henna at the tips. The shoulders of her skimpy, decent, black dress were white with dandruff. She had a brisk air of bristle, like a terrier bitch. There was ex-whore written all over her. Excavating a glass jar from the rubble on the dressing-table, she dug out a handful of cold cream with her crooked claw and slapped it, splat! on Fevvers’ face.

‘You ’ave a spot more wine, ducky, while you’re waiting,’ she offered Walser, scouring away at her charge with a wad of cotton wool. ‘It didn’t cost us nothing. Some jook give it you, didn’t ’e. There, darling . . .’ wiping off the cold cream, suddenly, disconcertingly, tenderly caressing the aerialiste with the endearment.

‘It was that French jook,’ said Fevvers, emerging beefsteak red and gleaming. ‘Only the one crate, the mean bastard. Have a drop more, for Gawd’s sake, young feller, we’re leaving you behind! Can’t have the ladies pissed on their lonesome, can we? What kind of a gent are you?’

Extraordinarily raucous and metallic voice; clanging of contralto or even baritone dustbins. She submerged beneath another fistful of cold cream and there was a lengthy pause.

Oddly enough, in spite of the mess, which resembled the aftermath of an explosion in a corsetière’s Fevvers’ dressingroom was notable for its anonymity. Only the huge poster with the scrawled message in charcoal: Toujours, Toulouse, and that was only self-advertisement, a reminder to the visitor of that part of herself which, off-stage, she kept concealed. Apart from that, not even a framed photograph propped amongst the unguents on her dressing-table, just a bunch of Parma violets stuck in a jam-jar, presumably floral overspill from the mantelpiece. No lucky mascots, no black china cats nor pots of white heather. Neither personal luxuries such as armchairs or rugs. Nothing to give her away. A star’s dressing-room, mean as a kitchenmaid’s attic. The only bits of herself she’d impressed on her surroundings were those few blonde hairs striating the cake of Pears transparent soap in the cracked saucer on the deal washstand.

The blunt end of an enamelled hip bath full of suds of earlier ablutions stuck out from behind a canvas screen, over which was thrown a dangling set of pink fleshings so that at first glance you might have thought Fevvers had just flayed herself. If her towering headdress of dyed ostrich plumes were unceremoniously shoved into the grate, Lizzie had treated the other garment in which her mistress made her first

appearance before her audience with more respect, had shaken out the robe of red and purple feathers, put it on a wooden hanger and hung it from a nail at the back of the dressing-room door, where its ciliate fringes shivered continually in the draught from the ill-fitting windows.

On the stage of the Alhambra, when the curtain went up, there she was, prone in a feathery heap under this garment, behind tinsel bars, while the band in the pit sawed and brayed away at ‘Only a bird in a gilded cage’. How kitsch, how apt the melody; it pointed up the element of the meretricious in the spectacle, reminded you the girl was rumoured to have started her career in freak shows. (Check, noted Walser.) While the band played on, slowly, slowly, she got to her knees, then to her feet, still muffled up in her voluminous cape, that crested helmet of red and purple plumes on her head; she began to twist the shiny strings of her frail cage in a perfunctory way, mewing faintly to be let out.

A breath of stale night air rippled the pile on the red plush banquettes of the Alhambra, stroked the cheeks of the plaster cherubs that upheld the monumental swags above the stage.

From aloft, they lowered her trapezes.

As if a glimpse of the things inspired her to a fresh access of energy, she seized hold of the bars in a firm grip and, to the accompaniment of a drum-roll, parted them. She stepped through the gap with elaborate and uncharacteristic daintiness. The gilded cage whisked up into the flies, tangling for a moment with the trapeze.

She flung off her mantle and cast it aside. There she was.

In her pink fleshings, her breastbone stuck out like the prow of a ship; the Iron Maiden cantilevered herbosom whilst paring down her waist to almost nothing, so she looked as if she might snap in two at any careless movement. The leotard was adorned with a spangle of sequins on her crotch and nipples, nothing else. Her hair was hidden away under the dyed plumes that added a good eighteen inches to her already immense height. On her back she bore an airy burden of furled plumage as gaudy as that 12

of a Brazilian cockatoo. On her red mouth there was an artificial smile.

Look at me! With a grand, proud, ironic grace, she exhibited herself before the eyes of the audience as if she were a marvellous present too good to be played with. Look, not touch.

She was twice as large as life and as succinctly finite as any object that is intended to be seen, not handled. Look! Hands off!

Look at me!

She rose up on tiptoe and slowly twirled round, giving the spectators a comprehensive view of her back: seeing is believing. Then she spread out her superb, heavy arms in a backwards gesture of benediction and, as she did so, her wings spread, too, a polychromatic unfolding fully six feet across, spread of an eagle, a condor, an albatross fed to excess on the same diet that makes flamingoes pink.

Oooooooh! The gasps of the beholders sent a wind of wonder rippling through the theatre.

But Walser whimsically reasoned with himself, thus: now, the wings of the birds are nothing more than the forelegs, or, as we should say, the arms, and the skeleton of a wing does indeed show elbows, wrists and fingers, all complete. So, if this lovely lady is indeed, as her publicity alleges, a fabulous bird-woman, then she, by all the laws of evolution and human reason, ought to possess no arms at all, for it’s her arms that ought to be her wings!

Put it another way: would you believe a lady with four arms, all perfect, like a Hindu goddess, hinged on either side of those shoulders of a voluptuous stevedore? Because, truly, that is the real nature of the physiological anomaly in which Miss Fevvers is asking us to suspend disbelief.

Now, wings without arms is one impossible thing; but wings with arms is the impossible made doubly unlikely – the impossible squared. Yes, sir!

In his red-plush press box, watching her through his operaglasses, he thought of dancers he had seen in Bangkok,

presenting with their plumed, gilded, mirrored surfaces and angular, hieratic movements, infinitely more persuasive illusions of the airy creation than this over-literal winged barmaid before him. ‘She tries too damn’ hard,’ he scribbled on his pad.

He thought of the Indian rope trick, the child shinning up the rope in the Calcutta market and then vanishing clean away; only his forlorn cry floated down from the cloudless sky. How the white-robed crowd roared when the magician’s basket started to rock and sway on the ground until the child jumped out of it, all smiles! ‘Mass hysteria and the delusion of crowds . . . a little primitive technology and a big dose of the will to believe.’ In Kathmandu, he saw the fakir on a bed of nails, all complete, soar up until he was level with the painted demons on the eaves of the wooden houses; what, said the old man, heavily bribed, would be the point of the illusion if it looked like an illusion? For, opined the old charlatan to Walser with po-faced solemnity, is not this whole world an illusion? And yet it fools everybody.

Now the pit band ground to a halt and rustled its scores. After a moment’s disharmony comparable to the clearing of a throat, it began to saw away as best it could at – what else – ‘The Ride of the Valkyries’. Oh, the scratch unhandiness of the musicians! the tuneless insensitivity of their playing! Walser sat back with a pleased smile on his lips; the greasy, inescapable whiff of stage magic which pervaded Fevvers’ act manifested itself abundantly in her choice of music.

She gathered herself together, rose up on tiptoe and gave a mighty shrug, in order to raise her shoulders. Then she brought down her elbows, so that the tips of the pin feathers of each wing met in the air above her headdress. At the first crescendo, she jumped.

Yes, jumped. Jumped up to catch the dangling trapeze, jumped up some thirty feet in a single, heavy bound, transfixed the while upon the arching white sword of the limelight. The invisible wire that must have hauled her up remained invisible. She caught hold of the trapeze with one hand. Her wings 14

throbbed, pulsed, then whirred, buzzed and at last began to beat steadily on the air they disturbed so much that the pages of Walser’s notebook ruffled over and he temporarily lost his place, had to scramble to find it again, almost displaced his composure but managed to grab tight hold of his scepticism just as it was about to blow over the ledge of the press box.

First impression: physical ungainliness. Such a lump it seems! But soon, quite soon, an acquired grace asserts itself, probably the result of strenuous exercise. (Check if she trained as a dancer.)

My, how her bodice strains! You’d think her tits were going to pop right out. What a sensation that would cause; wonder she hasn’t thought of incorporating it in her act. Physical ungainliness in flight caused, perhaps, by absence of tail, the rudder of the flying bird – I wonder why she doesn’t tack a tail on the back of her cache-sexe; it would add verisimilitude and, perhaps, improve the performance. What made her remarkable as an aerialiste, however, was the speed – or, rather the lack of it – with which she performed even the climactic triple somersault. When the hack aerialiste, the everyday, wingless variety, performs the triple somersault, he or she travels through the air at a cool sixty miles an hour; Fevvers, however, contrived a contemplative and leisurely twenty-five, so that the packed theatre could enjoy the spectacle, as in slow motion, of every tense muscle straining in her Rubenesque form. The music went much faster than she did; she dawdled. Indeed, she did defy the laws of projectiles, because a projectile cannot mooch along its trajectory; if it slackens its speed in mid-air, down it falls. But Fevvers, apparently, pottered along the invisible gangway between her trapezes with the portly dignity of a Trafalgar Square pigeon flapping from one proffered handful of corn to another, and then she turned head over heels three times, lazily enough to show off the crack in her bum.

(But surely, pondered Walser, a real bird would have too much sense to think of performing a triple somersault in the first place.)

Yet, apart from this disconcerting pact with gravity, which surely she made in the same way the Nepali fakir had made his, Walser observed that the girl went no further than any other trapeze artiste. She neither attempted nor achieved anything a wingless biped could not have performed, although she did it in a different way, and, as the Valkyries at last approached Valhalla, he was astonished to discover that it was the limitations of her act in themselves that made him briefly contemplate the unimaginable – that is, the absolute suspension of disbelief.

For, in order to earn a living, might not a genuine birdwoman – in the implausible event that such a thing existed –have to pretend she was an artificial one?

He smiled to himself at the paradox: in a secular age, an authentic miracle must purport to be a hoax, in order to gain credit in the world. But – and Walser smiled to himself again, as he remembered his flutter of conviction that seeing was believing – what about her belly button? Hasn’t she just this minute told me she was hatched from an egg, not gestated in utero? The oviparous species are not, by definition, nourished by the placenta; therefore they feel no need of the umbilical cord . . . and, therefore, don’t bear the scar of its loss! Why isn’t the whole of London asking: does Fevvers have a belly button?

It was impossible to make out whether or not she had a navel during her act; Walser could recall, of her belly, only a pink, featureless expanse of stockinette fleshing. Whatever her wings were, her nakedness was certainly a stage illusion.

After she’d pulled off the triple somersault, the band performed the coup de grâce on Wagner, and stopped. Fevvers hung by one hand, waving and blowing kisses with the other, those famous wings of hers now drawn up behind her. Then she jumped right down to the ground, just dropped, just plummeted down, hitting the stage squarely on her enormous feet with an all too human thump only partially muffled by the roar of applause and cheers.

Bouquets pelt the stage. Since there is no second-hand market for flowers, she takes no notice of them. Her face,

thickly coated with rouge and powder so that you can see how beautiful she is from the back row of the gallery, is wreathed in triumphant smiles; her white teeth are big and carnivorous as those of Red Riding Hood’s grandmother.

She kisses her free hand to all. She folds up her quivering wings with a number of shivers, moues and grimaces as if she were putting away a naughty book. Some chorus boy or other trips on and hands her into her feather cloak that is as frail and vivid as those the natives of Florida used to make. Fevvers curtsies to the conductor with gigantic aplomb and goes on kissing her hand to the tumultuous applause as the curtain falls and the band strikes up ‘God save the Queen’. God save the mother of the obese and bearded princeling who has taken his place in the royal box twice nightly since Fevvers’ first night at the Alhambra, stroking his beard and meditating upon the erotic possibilities of her ability to hover and the problematic of his paunch vis-à-vis the missionary position.

The greasepaint floated off Fevvers’ face as Lizzie wiped away cold cream with cotton wool, scattering the soiled balls carelessly on the floor. Fevvers reappeared, flushed, to peer at herself eagerly in the mirror as if pleased and surprised to find herself again so robustly rosy-cheeked and shiny-eyed. Walser was surprised at her wholesome look: like an Iowa cornfield.

Lizzie dipped a velour puff in a box of bright peachcoloured powder and shook it over the girl’s face, to take off the shine. She picked up a hairbrush of yellow metal.

‘Can’t tell you who give ’er this,’ she announced conspiratorially waving the brush so that the small stones with which it was encrusted (in the design of the Prince of Wales’ feathers) scattered prisms of light. ‘Palace protocol. Dark secret. Comb and mirror to go with it. Solid, it is. What a shock I got when I got it valued. Fool and his money is soon parted. Goes straight into the bank tomorrow morning. She’s no fool. All the same, she can’t resist using it tonight.’

There was a hint of censure in Lizzie’s voice, as if there was nothing that she herself would find irresistible, but Fevvers

eyed her hairbrush with a complacent and proprietorial air. For just one moment, she looked less generous.

‘Course,’ said Fevvers, ‘he never got nowhere.’

Her inaccessability was also legendary, even if, as Walser had already noted on his pad, she was prepared to make certain exceptions for exigent French dwarves. The maid untied the blue ribbon that kept in check the simmering wake of the young woman’s hair, which she laid over her left arm as if displaying a length of carpet and started to belabour vigorously. It was a sufficiently startling head of hair, yellow and inexhaustible as sand, thick as cream, sizzling and whispering under the brush. Fevvers’ head went back, her eyes half closed, she sighed with pleasure. Lizzie might have been grooming a palomino; yet Fevvers was a hump-backed horse.

That grubby dressing-gown, horribly caked with greasepaint round the neck . . . when Lizzie lifted up the armful of hair, you could see, under the splitting, rancid silk, her humps, her lumps, big as if she bore a bosom fore and aft, her conspicuous deformity, the twin hills of the growth she had put away for those hours she must spend in daylight or lamplight, out of the spotlight. So, on the street, at the soirée, at lunch in expensive restaurants with dukes, princes, captains of industry and punters of like kidney, she was always the cripple, even if she always drew the eye and people stood on chairs to see.

‘Who makes your frocks?’ the reporter in Walser asked percipiently. Lizzie stopped in mid-stroke; her mistress’s eyes burst open – whoosh! like blue umbrellas.

‘Nobody. I meself,’ said Fevvers sharply. ‘Liz helps.’

‘But ’er ’ats we purchase from the best modistes,’ asserted Lizzie suavely. ‘We got some lovely ’ats in Paris, didn’t we, darling? That leghorn, with the moss roses . . .’

‘I see his glass is empty.’

Walser allowed himself to be refilled before Lizzie stuffed her mouth with tortoiseshell pins and gave both hands to the task of erecting Fevvers’ chignon. The sound of the music hall

at closing time clanked and echoed round them, gurgle of water in a pipe, chorus girls calling their goodnights as they scampered downstairs to the waiting hansoms of the stagedoor Johnnies, somewhere the rattle of an out-of-tune piano. The lightbulbs round Fevvers’ mirror threw a naked and unkind light upon her face but could flush out no flaw in the classic cast of her features, unless their very size was a fault in itself, the flaw that made her vulgar.

It took a long time to pile up those two yards of golden hair. By the time the last pin went in, silence of night had fallen on the entire building.

Fevvers patted her bun with a satisfied air. Lizzie shook the champagne bottle, found it was empty, tossed it into a corner, took another from a crate stored behind the screen, popped it, refilled all glasses. Fevvers sipped and shuddered.

‘Warm.’

Lizzie peered in the toilet jug and tipped the melted contents into the bathwater.

‘No more ice,’ she said to Walser accusingly, as if it were his fault.

Perhaps, perhaps . . . my brain is turning to bubbles already, thought Walser, but I could almost swear I saw a fish, a little one, a herring, a sprat, a minnow, but wriggling, alive-oh, go into the bath when she tipped the jug. But he had no time to think about how his eyes were deceiving him because Fevvers now solemnly took up the interview shortly before the point where she’d left off.

‘Hatched,’ she said.

‘Hatched; by whom, I do not know. Who laid me is as much a mystery to me, sir, as the nature of my conception, my father and my mother both utterly unknown to me, and, some would say, unknown to nature, what’s more. But hatch out I did, and put in that basket of broken shells and straw in Whitechapel at the door of a certain house, know what I mean?’

As she reached for her glass, the dirty satin sleeve fell away from an arm as finely turned as the leg of the sofa on which Walser sat. Her hand shook slightly, as if with suppressed emotion.

‘And, as I told you, who was it but my Lizzie over there who stumbled over the mewing scrap of life that then I was whilst she’s assisting some customer off the premises and she brings me indoors and there I was reared by these kind women as if I was the common daughter of half-a-dozen mothers. And that is the whole truth and nothing but, sir.

‘And never have I told it to a living man before.’

As Walser scribbled away, Fevvers squinted at his notebook in the mirror, as if attempting to interpret his shorthand by some magic means. Her composure seemed a little ruffled by his silence.

‘Come on, sir, now, will they let you print that in your newspapers? For these were women of the worst class and defiled.’

‘Manners in the New World are considerably more elastic than they are in the old, as you’ll be pleased to find, ma’am,’ said Walser evenly. ‘And I myself have known some pretty decent whores, some damn’ fine women, indeed, whom any man might have been proud to marry.’ 20

‘Marriage? Pah!’ snapped Lizzie in a pet. ‘Out of the frying pan into the fire! What is marriage but prostitution to one man instead of many? No different! D’you think a decent whore’d be proud to marry you, young man? Eh?’

‘Never mind, Lizzie, ’e means well. Here, is the boy still on? I’m starved to death, I’d pawn me gold hairbrush for some eel pies and a saveloy.’ She turned to Walser with gigantic coquetry. ‘Could you fancy an eel pie and a bit of mash, sir?’

The call-boy was rung for, proved to be still on duty and instantly despatched to the pie shop in the Strand by a Lizzie still stiff with affront. But she was soon mollified by the spread that arrived in a covered basket ten minutes later – hot meat pies with a glutinous ladleful of eel gravy on each; a Fujiyama of mashed potatoes; a swamp of dried peas cooked up again and served swimming in greenish liquor. Fevvers paid off the call-boy, waited for her change and tipped him with a kiss on his peachy, beardless cheek that left it blushing and a little greasy. The women fell to with a clatter of rented cutlery but Walser himself opted for another glass of tepid champagne.

‘English food . . . waaall, I find it’s an acquired taste; I account your native cuisine to be the eighth wonder of the world, ma’am.’

She gave him a queer look, as if she suspected he were teasing and, sooner or later, she would remember to pay him back for it, but her mouth was too full for a ripost as she tucked into this earthiest, coarsest cabbies’ fare with gargantuan enthusiasm. She gorged, she stuffed herself, she spilled gravy on herself, she sucked up peas from the knife; she had a gullet to match her size and table manners of the Elizabethan variety. Impressed, Walser waited with the stubborn docility of his profession until at last her enormous appetite was satisfied; she wiped her lips on her sleeve and belched. She gave him another queer look, as if she half hoped the spectacle of her gluttony would drive him away, but, since he remained, notebook on knee, pencil in hand, sitting on her sofa, she sighed, belched again, and continued:

‘In a brothel bred, sir, and proud of it, if it comes to the point, for never a bad word nor an unkindness did I have from my mothers but I was given the best of everything and always tucked up in my little bed in the attic by eight o’clock of the evening before the big spenders who broke the glasses arrived.

‘So there I was –’

‘– there she was, the little innocent, with her yellow pigtails that I used to tie up with blue ribbons, to match her big blue eyes –’

‘– there I was and so I grew, and the little downy buds on my shoulders grew with me, until, one day, when I was seven years old, Nelson –’

‘Nelson?’ queried Walser.

Fevvers and Lizzie raised their eyes reverently in unison to the ceiling.

‘Nelson, rest her soul, yes. Wasn’t she the madame! And always called Nelson, on account of her one eye, a sailor having put the other out with a broken bottle the year of the Great Exhibition, poor thing. Now Nelson ran a seemly, decent house and never thought of putting me to the trade while I was still in short petticoats, as others might have. But, one evening, when she and my Lizzie were giving me my bath in front of the fire, as she was soaping my little feathery buds very tenderly, she cries out: “Cupid! Why, here’s our very own Cupid in the living flesh!” And that was how I first earned my crust, for my Lizzie made me a little wreath of pink cotton roses and put it on my head and gave me a toy bow and arrow –’

‘– that I gilded up for her,’ said Lizzie. ‘Real gold leaf, it was. You put the leaf on the palm of your hand. Then you blow it ever so lightly onto the surface of whatever it is you want gilded. Gently does it. Blow it. Gawd, it was a bother.’

‘So, with my wreath of roses, my baby bow of smouldering gilt and my arrows of unfledged desire, it was my job to sit in the alcove of the drawing-room in which the ladies introduced themselves to the gentlemen. Cupid, I was.’