‘A book that everyone should read’ THE TIMES

‘A book that everyone should read’ THE TIMES

takashi nagai

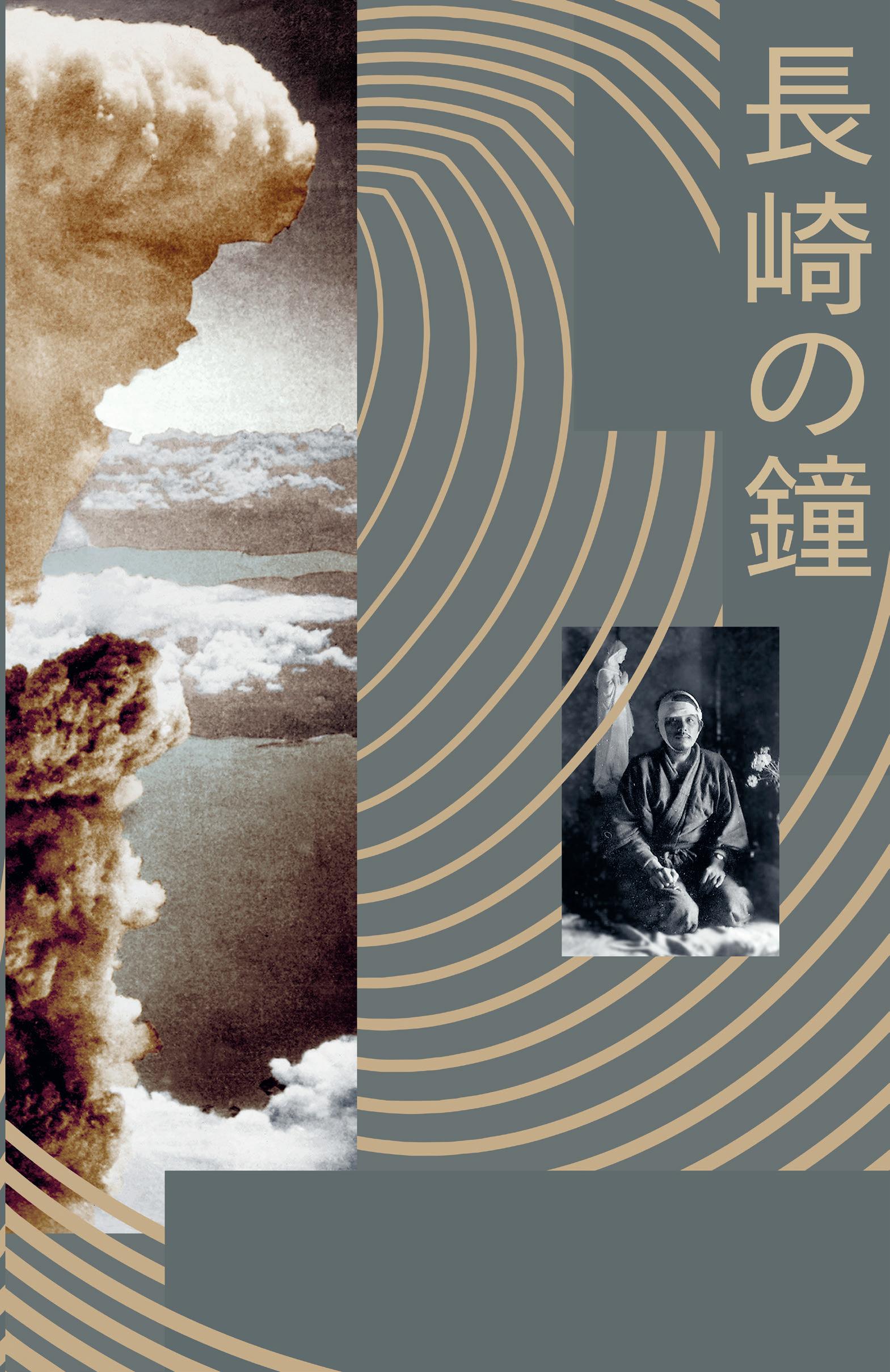

Takashi Nagai was a Catholic physician, author and survivor of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki. Born in 1908 in the Japanese city of Matsue, Nagai travelled to Nagasaki to study medicine and later became the dean of the radiology department at Nagasaki Medical University Hospital. He died from leukaemia in 1951.

William Johnston was born in 1925 in Belfast, Northern Ireland. He joined the Jesuit Order in 1943 and after completing his studies at the University of Dublin, travelled to Japan in 1951. There, he taught English literature while earning a PhD in Theology, and later wrote a number of books on religion and mysticism. He died in 2010 at the age of 85.

trans L ated fr OM the J apanese by William Johnston

W ith an intr O ducti O n by Richard Lloyd Parry

Vintage Classics is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies

Vintage, Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW

penguin.co.uk/vintage-classics global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Translation copyright © Society of Jesuit Japan Province, 1985 Introduction copyright © Richard Lloyd Parry, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

This edition published in Vintage Classics in 2025

First published as Nagasaki no Kane by Hibiya Publisher in 1949

Text files provided by the Nagasaki Nyoko Association

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 9781529952605

Typeset in 12/14.75pt Bembo Book MT Pro by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d02 yh68

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

The Bells of Nagasaki is famous as an eyewitness account of the world’s second and last atomic bombing, but its climax is an example of that venerable literary form, the sermon. In life, it was delivered by Takashi Nagai, doctor and church leader, three months after the dropping of the A-bomb in August 1945 that killed an estimated 75,000 of Nagasaki’s people, including some 8,000 of its Roman Catholics. A congregation of survivors, many of them injured and sick, gathered in the ruins of the city’s cathedral in November, to hold a collective funeral service for the dead, plenty of whose remains would never be recovered or identified. In his book, though, Nagai chooses not to describe this great and emotional public event, but an earlier private meeting with an old friend and fellow Catholic, Ichitaro Yamada.

Demobilised from the army, Yamada has returned to find his home city destroyed and his wife and five children killed by the bomb. He is stricken not only by grief, but by horror at the spiritual implications of their deaths. ‘The atomic bomb was a punishment from heaven,’ he tells Nagai. ‘Those who survived received a special grace from God. But then . . . does that mean that my wife and children were evil people?’

Nagai too has lost his wife, their home and the university

hospital where he worked. He is slowly dying of leukaemia; his two children, who survived the bomb, will soon be orphans. The two friends meet in the tiny, draughty shack where Nagai lies, immobilised by illness, in a landscape of ashes. In the ten chapters preceding, we have followed his heroic efforts as survivor, doctor and father; and it is in this intimate, domestic setting, in the meeting between two seemingly broken men, that the famous eulogy appears, as Nagai presents a draft of it to Yamada.

The reader, like the congregation in the ruined cathedral, may think that they know what to expect – expressions of consolation and reassurance about God’s love and Christ’s redemptive suffering and sacrifice. But Nagai goes further in a way that is both dramatic and shocking. Over the previous one hundred and forty pages, he has described unsparingly the death and suffering inflicted by the bomb, and the agony of its survivors. Now, in the closing moments of the book, he sets out a radical reimagining of the end of the Second World War on an epic spiritual scale.

He begins by pointing out a series of curious facts. The American planes that destroyed Nagasaki had originally been bound for another target, the city of Kokura, which was obscured by cloud. Having diverted at the last minute to Nagasaki, they missed the city centre and destroyed instead the northern suburb of Urakami, home to the largest population of Christians in Japan. Six days later on 15 August, Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s surrender on what

happened to be the Feast of the Assumption of Mary. On this shallow foundation of coincidence, Nagai erects a theology of the atomic bombing that turns his friend’s despair on its head. The attack, he explains, was not the work of the American air force, but ‘the providence of God’. The terrible sin of war demanded ‘the offering of a great sacrifice’. Previous cities, including Hiroshima, had faced destruction by conventional, as well as nuclear bombing, but ‘only when Nagasaki was destroyed did God accept the sacrifice.’ In other words, He chose Nagasaki – because of, not despite, its Christian population – ‘as a victim, a pure lamb, to be slaughtered and burned on the altar of sacrifice to expiate the sins committed by humanity in the Second World War’. Even Hirohito, descendant of the Shinto gods, was a toy in the hands of the Christian deity who ‘inspired the emperor to issue the sacred decree by which the war was brought to an end’.

How noble, how splendid was that holocaust of August 9, when flames soared up from the cathedral, dispelling the darkness of war and bringing the light of peace! In the very depth of our grief we reverently saw here something beautiful, something pure, something sublime. Eight thousand people, together with their priests, burning with pure smoke, entered into eternal life.

It is a vision like a scene from Paradise Lost, or one of those vast baroque paintings of the last judgement, but cluttered with

generals, B-29s and mushroom clouds, rather than angels, saints and golden chariots. ‘Let us give thanks that Urakami was chosen for this sacrifice,’ Nagai concludes, ‘Let us give thanks that through this sacrifice peace was given to the world.’ When he delivered these words there were jeers and heckles of indignation, as well as sobs of relief, in the ruins of the cathedral. The sermon, and the book in which it appeared, were turning points for Japan, Nagasaki and Nagai himself. The Bells of Nagasaki was a bestseller, among people with little knowledge of, or interest in, Christianity. It was turned into a successful film, whose theme song was also a popular hit. Its author, who published a dozen other books, became a celebrity. Famous people travelled across the world to meet him in his hut during the remaining few years of his life; others denounced him as the useful idiot of war criminals and their apologists. Eighty years later, it is as thrilling and jolting as ever to read a book that manages at once to be an unflinching account of nuclear horror, a desperate plea for peace and that impossibly perverse thing: a hymn of praise for the atomic bomb.

Nagai was born in 1908 in Shimane prefecture, close to Izumo Taisha, the second-ranking of the great Shinto shrines of Japan. He grew up in a tense, fertile period of Japanese intellectual history when notions of individual liberty, fuelled by translations of Western writing, were flourishing in parallel with an increasingly bigoted and militaristic nationalism. Similar

tensions – between rationalism and intuition, native tradition and foreign ideas – marked his intellectual development. He studied medicine at Nagasaki University, but read deeply in Japanese classical poetry, as well as Pascal and the Zen monk Dogen, who alerted him to the insights to be achieved through faith and intuition, as well as reason. The sudden death of his mother left him with intimations of the survival of the soul, but he was also conscious of the trap of wishful thinking, of believing in something not because it was true, but because it numbed the pain of loss.

Unlike Hiroshima, a stolidly dull military and industrial centre, Nagasaki had for centuries been one of the most beautiful, interesting and cosmopolitan cities in Japan. It was to its famous harbour that Dutch and Portuguese ships brought European learning and technology in the sixteenth century, along with Christian missionaries. After the new faith was suppressed in a series of brutal persecutions and martyrdoms, ‘hidden Christians’ continued to worship in secret, handing down garbled liturgies until the country opened up again in the late nineteenth century. As a medical student, Nagai enjoyed the profane side of the port city – the author of his English-language biography, Father Paul Glynn, records that ‘he was not unknown in the bars down by the docks – bars equipped with women of easy virtue – where he sometimes drank large quantities of sake.’ But he lodged with a family of devout Roman Catholics, whose ancestors had been tortured and imprisoned under the shogunate.

Urakami, where they lived, was the most concentratedly Christian place in Japan; its cathedral was said to be the biggest church in Asia. Nagai became fascinated by the idea of martyrdom, exemplified by the twenty-six Japanese and foreign Catholics who were crucified in the city in 1597 after the suppression of Christianity by the shogunate. He graduated at the top of his year and joined the university’s department of radiology to become a specialist in the science of X-rays. In 1933, he was called up into the army and spent a year fighting Chinese resistance to Japan’s colonisation of Manchuria. He wrote conventionally patriotic letters cheering on the imperial cause, but was troubled by the spectacle of butchered civilians and maimed comrades. ‘He wanted to believe there was some meaning to the universe, and to the deaths of young soldiers . . . and to the deaths of his mother and the Chinese mothers and children and soldiers,’ writes Glynn. ‘But if he plunged blindly into faith and prayer, would it not be the cowardice of surrender?’

He was also falling in love with Midori, the daughter of his landlord, and on his return from the front, he began going with her to mass at Urakami Cathedral. He was baptised as a Roman Catholic, in defiance of both his father and the growing spirit of Shinto nationalism, taking the name Paul, after the leader of the Twenty-Six Martyrs. After marrying Midori, he was shipped out for two and a half more years at the Manchurian front, but he was back in Nagasaki in December 1941 when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor and

declared war on the United States and the British Empire. His attitude towards the Pacific War was one common among Japanese intellectuals of the time. Privately, he was contemptuous of the army generals and their hopeless faith that ‘fighting spirit’ alone could overcome American technological and economic superiority; publicly, he cooperated enthusiastically in the duties assigned to him.

As well as treating the victims of conventional air raids, he set up a mass screening programme for tuberculosis. Deprived of assistants by the call-up, he insisted on performing the X-rays himself, in excess of well-established safe limits for radiation exposure. He began to suffer from shaking, night sweats and exhaustion; he was diagnosed with leukaemia and given three years to live. By the time the atomic bomb fell on Nagasaki on 9 August 1945, he was already dying of radiation sickness, a martyr not to faith or war, but to science.

There are many survivor accounts of the atomic bombings but the early pages of The Bells of Nagasaki rank among the best. The point of comparison for many readers in English will be John Hersey’s Hiroshima, a tightly disciplined and solemn masterpiece of narrative journalism. Nagai’s is an altogether odder and more eccentric work, meandering and digressive, with shifting points of view and startling flashes of humour. As a vision of the strange hells of destruction and suffering in the immediate aftermath of the bomb, it has not been bettered. Nagai has a gift for precise but unexpected

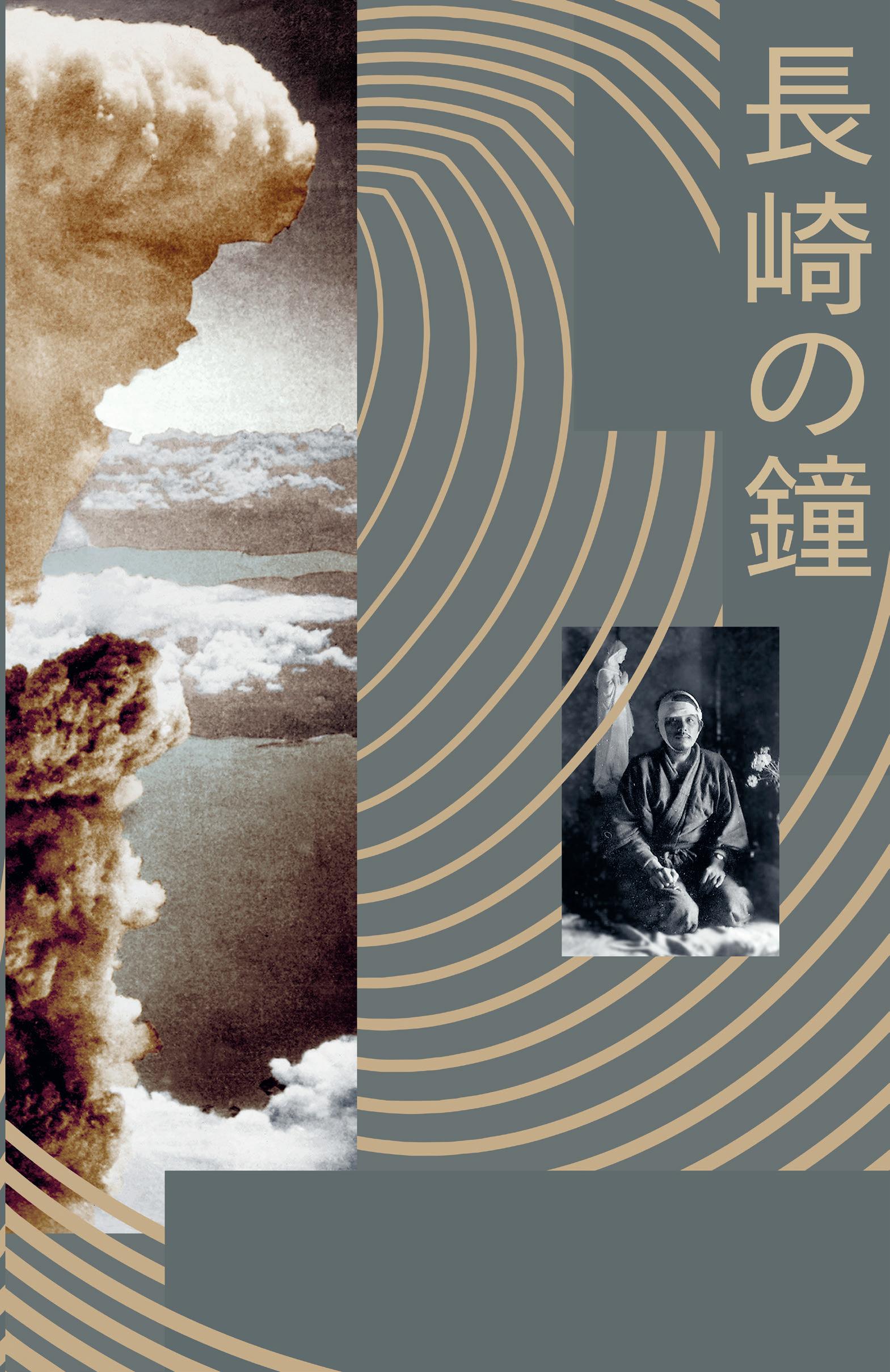

description and a knack for slowing down time. Caught inside a university building, 600 yards from the centre of the explosion, he watches ‘pieces of broken glass . . . like leaves blown off a tree in a whirlwind’. Floored by the blast, he is ‘flattened like a rice cracker lying in a toaster’. The famous mushroom cloud is ‘like a huge lantern wrapped in cotton . . . inside a red fire seemed to be blazing and something like beautiful electric lights flashed incessantly.’

The unflinching, almost icy, objectivity of the doctor adds to the horror of the scenes he recounts:

A young woman ran clutching a headless child. An aged couple, hand in hand, slowly climbed the mountain. As she ran, a girl’s clothes burst into flames and she fell writhing in a ball of fire. On top of a roof that was enveloped in flames, I saw a man dancing and singing wildly: he was out of his mind.

Such level-eyed calm makes it possible to miss how close Nagai himself was to death, even as he treated the bomb’s burned and dying victims, with one had pressed against his temple. ‘Whenever I removed this hand in order to attend to a patient’s wound, the blood would spurt out like red ink from a water pistol, splattering the wall and the shoulder of the chief nurse,’ he writes. ‘But since it was a small artery, I thought my body would hold out for about three hours.’

For all the accumulated detail, the first part of the book

is also striking for what it omits: above all, any mention of Nagai’s family, or his faith. In contemplating the destruction around him, he never once appeals to, berates or even mentions God. We know from his other accounts that it was two days before Nagai went to the site of his home. There he found his wife’s charred bones (their children had been safely evacuated to the countryside); he gathered the remains in a bucket, and retrieved the lump of molten glass and metal that had been her rosary. But here he omits this wrenching scene completely, to provide instead an account of the selfless first aid efforts of the university’s surviving doctors and nurses, and an almost unbearable description of the range of injuries caused by the bomb. For, apart from being a powerful work of personal witness and religious consolation, The Bells of Nagasaki is also a strange and compelling book about scientists.

Other Roman Catholics, and other doctors, have described the bombings. What makes Nagai unique as a writer is that he was a scientist specialising in radiation present at the dawn of the nuclear age. As a victim, the bombing is a personal human catastrophe; as a Christian, it is a challenge to his religious faith. But he also regards it with the admiring and competitive scrutiny of a scientist who would love to have seen his own side pull off such a feat.

One of the most remarkable passages is a conversation, technical in character, about the working of the atomic bomb, the day after it fell, by its direct victims. ‘Did we

know all this in Japan?’ asks one speaker, after a long and expertly informed discussion about the state of research into nuclear fission and the international personalities –Einstein, Compton, Chadwick, Meitner – distinguished in the field.

‘Yes, we did. Even I knew this much.’

‘Then why didn’t we do it?’

‘. . . They said the army couldn’t be allowed to spend so much money on research that was little more than a dream . . .’

‘What a pity!’

‘No use regretting what’s past. It is really unfortunate when wise people have ignorant leaders . . .’

‘. . . Well, we can’t deny that it is a tremendous scientific achievement, this atomic bomb!’

The jolting, almost grotesque, effect on a modern reader is part of the value of The Bells of Nagasaki. As well as plenty of other things, it is a primary source that preserves in raw form ironies and complexities that have been forgotten in the decades since 1945. The atomic bombs have become so laden with politics and symbolism, the debate about their morality so polarised, that it is difficult now to imagine a world in which a man who had lost his wife and close friends to the bomb could also, without any sense of dissonance, regard it as a scientific marvel.