THIRSTY

100 Great Wines and Stories

Tom Gilbey, aka the Wine Guy

Square Peg, an imprint of Vintage, is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies

Vintage, Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW penguin.co.uk/vintage global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published by Square Peg in 2025

Copyright © Tom Gilbey 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Illustrations © Hugo Guinness

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset in 12.5/15.2pt Garamond Premier Pro by Six Red Marbles UK, Thetford, Norfolk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781529951479

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

To

Caroline Gilbey, my dear mum

Welcome: Greetings from the Wine Guy

Thank you for picking up this book. A book about me, I’m afraid . . . and quite a lot of wine. But this isn’t a ‘wine book’, at least not in the traditional sense. There are very many such books out there, reference guides far better than I could ever write, many of which I own and cherish.

Thirsty is a bit different. It’s a book of stories, revealing the ups and downs of my life in wine – plus a curated list of 100 bottles – and, as you’ll find out if you read a bit further, it’s also an exploration of why wine is at the very centre of my being, and how it can enrich our lives. Some say wine is a drink for crusty old dads. For me, it’s an elixir made and sold by passionate eccentrics who’ve taught me to adventure as far into the glass as I dare – no inhibitions, no right, no wrong, no price too low or too high . . . and it’s been a blast.

And, crucially, it’s been a jolly good time getting to know you all and making this Wine Wanker (as my son and business partner Fred has christened me) book for you, reader. Without your support and curiosity for the endless jollies I somehow wind up on, none of this would be possible. So, cheers, and please, charge your glass, ideally with a cool white, pink or orange, or a mellow red, or perhaps something bubbly, and join me, reminiscing on a life filled with wine . . .

Introduction

Wine has been in my veins, not literally of course, from the moment I popped into this world, over half a century ago. A family affair, my mum and dad made their living from it, running a wine bar and restaurant on Eton High Street, across the bridge from Windsor Castle in Berkshire. (We lived in a little village thirty minutes’ drive away, Waltham Saint Lawrence, right in the centre, handily enough next door to the village pub.) But the Gilbeys’ love of wine started long before then. Our ancestors have been in the booze trade since the nineteenth century, and in the 1940s, my family was responsible for the sale of a third of all bottles of wine in the UK . Called, imaginatively, Gilbeys and most famous for their gin, the old family firm also came up with one of the most successful Anglo- French wine collaborations of all time, Le Piat d’Or, a label launched in 1978 which, by 1983, was the most popular bottle of red on the UK ’s shelves.

It all started in 1857 with my great-great-great-grandfather, Alfred Gilbey, and his older brother Walter, who had returned the previous year from the Crimean War without a brass farthing to rub together, nor any particular skills. Either unwilling, or incapable of getting proper jobs, on the advice of their elder brother Henry, himself a partner in a wholesale wine merchants, the young duo started importing

good, cheap plonk from the Cape, South Africa, which they flogged from a six- foot trestle table on Oxford Street in London’s West End. Victorian bargain-booze-basement, I think you’d best describe it, but their South African wines proved so popular that after three years W. and A. Gilbey boasted over 20,000 happy customers. Ten years on, things were going so swimmingly that they’d progressed from their humble trestle table to owning their own office headquarters at one of the swankiest addresses on Oxford Street, the grand old Pantheon Theatre and Concert Hall – now home to Marks & Spencer.

By 1867 they’d also set up a gin distillery in Camden Town and begun to import wine from France . . . because it was cheaper. Oh yes, those two were quite the Robin Hoods of the wine world – making good grog available to all . . . and pocketing more than a few bob along the way, of course. Indeed, my Gilbey ancestors, for many years, were nailing it in the booze trade and, to top it all, in 1875, they were one of the first English families to buy a French vineyard, the seventeenth- century Château Loudenne, a large Bordeaux estate on the banks of the Gironde, in the Médoc. Well, it’s not exactly the magnifique Château Lafite Rothschild and definitely not a wine on which I’d stake my own reputation; nevertheless, those redoubtable and most enterprising Victorian brothers had their very own château. Visiting there now, you will find a museum displaying all the old vineyard tools, and sepia photographs of my ancestors with their handlebar moustaches, drinking tea in the garden and smoking pipes in thick tweed suits . . . in June. They were on the map.

Château Loudenne’s vineyards roll onto beautifully

manicured gardens which, in turn, roll straight down to the Gironde, the whopping estuary that leads to the Atlantic – and to Britain. The Gilbey brothers shipped thousands of barrels of the château wine home to London, and to their warehouses and bottling plant, sited alongside what is now the Camden Roundhouse arts venue. The Roundhouse itself was the turning depot for the trains which then left the warehouses, packed with Gilbeys booze to distribute throughout the country. Business was booming and before long Gilbeys were distilling their own spirits, Gilbeys Gin and Scotch Whisky.

The Gilbey passion for booze, but wine in particular, passed down through the generations, and such was this heritage that I’m not so sure some didn’t end up in my bottle as a toddler. No wonder then that I too followed in the family tradition. I’ve spent my whole working life in the wine trade, and it has taken me to places in the world I’d never otherwise have seen. And I’m still thirsty. Thirsty for more wine, more celebrations, flavours, travels and experiences. Thirsty for life, in fact, and for me, wine is always at the very heart of it. It’s the rich fuel for my enduring curiosity, enquiry and endeavours. I love that I will never know everything about wine; I love that it keeps evolving and diversifying; and that it keeps on delivering me new adventures and friendships. And that is the vital heartbeat of this book.

As my clapped- out, health- and- safety- defying bookshelves can attest, hundreds of terrific books have been written about wine. Their authors have taught me how to taste it, where it’s grown, how to buy it, but in Thirsty my aim is to cover something a bit different. For starters, here you will find no lists of dos and don’ts. In my book, there’s no right or

wrong way to drink or taste wine. If the most expensive red wine from Bordeaux is your bag, slurped from a coffee mug, then that’s absolutely fine – well actually, I’m no purist, but at least make sure the coffee cup’s clean. That said, I can’t tell you how many hours I’ve spent sitting through ‘proper’ wine tastings where people discuss malolactic fermentation and soil composition, and, yes, that’s all fascinating stuff. But, for me, the real joy of tasting wine is much less complicated than that. It’s about discovery. About finding something new in something as old as wine. Every bottle is a potential adventure, every glass a chance to taste something I’ve never tasted before. Yes, sometimes that quest serves me a corked wine or one that tastes like it’s been filtered through an old man’s sock. That’s all part of the fun, though. Because when I find a good one – a really good one – it’s pure joy in a glass. And I’m certainly not going to spit it out.

I want to show you how and why to love a wine – regardless of how expensive it is, what country it comes from, what colour it is, and even whether you think it’s any good or not. Believe me, just like you, I’ve tasted some ropey stuff in my time. Sometimes it’s while a ‘wine expert’ is extolling the virtues of said filth, too, preaching to me that it is ‘a quite magnificent vintage’, and that it’s this, that and everything else. Well, it’s for me to decide whether it’s magnificent or not, as it is for you as you thumb through this book, glass in hand, I hope.

I’ve never been one for being over-pedantic or getting too serious about the whole shebang. Wine transcends generations and is a drink best shared, over a meal with friends old and new, family and laughter. When the bottle begins to be the focus of the meal or the conversation, that’s when, I think,

it begins to lose its magic. When I pour a glass for anybody, the most I want to hear is, ‘Holy sh*t, Tom, what’s that? It’s the nuts.’ Then we can crack on with the fun stuff. And it’s fine, too, to offer no reaction at all – just simple contentment as the wine oils the wheels of happiness.

For me, the fun in my life has been in growing to really love and appreciate wine and everything that goes with it, before it and around it – I love the food, the places, the people, the history and the culture. I also love the fact that wine is not just to be enjoyed by some elite few – it’s accessible for all of us. Hell, the Romans chugged it down like water, and I’ve seen many a French wine grower dispensing their wine to their friends via petrol pumps, straight from the barrels; and now, even here in the UK , the humblest village or corner shop will probably stock something drinkable, maybe even good. Yet somehow it also inspires poets and politicians – lyrical wine enthusiasts may be too many to single out, but Churchill is reputed to have drunk a bottle of Pol Roger Champagne every day of his (adult, I hope) life.

I’ve peppered this book with stories from my past – those that I can remember – and a bit of history, too. I talk about a few characters who’ve had a big influence on my life, and many more I’ve crossed paths with. Wine brings people together. As I type, I recall pouring a glass of Sancerre for Stirling Moss, the British motor racing legend, one Saturday morning in 1991, aged nineteen, at my family’s restaurant, the Eton Wine Bar. It was just him sitting on one side of the bar, me behind, and no one else in the restaurant. As Mr Moss chomped his way through a smoked mackerel pâté and sipped from his glass, we got chatting about wine (safer territory to me than Formula One racing) and he insisted I join him for

a glass of Sancerre so I too, he told me, could smell the fresh hedgerow, cut grass and gooseberries.

Thirsty is about how I got into wine, how I learned about it. It’s about how sometimes I’ve ballsed things up with wine and how I’ve gained confidence with every new adventure. It’s the journey from my Francophile beginnings to my realisation that there is life beyond Beaujolais. It takes me from revelations in Australia to wines discovered in Bulgaria and beyond, and at the end of each chapter I’ve added a few takeaways that have been the building blocks of my learning, and a list of ten wines that have made me gaze at the ceiling in wonder – not necessarily the most expensive wines I’ve ever tried, but the ones that have really stood out for me.

At the start of each chapter I’ve put my ‘hero bottle’. Each of these bottles has been the inspiration for its chapter – not necessarily a masterpiece but a marker in time for me. One that will always bring a smile to my face.

Making mistakes has been integral to my growing to love wine. Disappointments in restaurants, wild choices in wine shops, and leaving bottles to age too long – the litany continues. Crucial, too, has been tasting, both taking part in organised tastings with the wine growers and the trade, and sharing bottles and glasses with friends, rejoicing in the successes and remembering those occasional disappointments.

I suppose my point is that I didn’t learn to love wine by buying the same bottle of Merlot from the supermarket week in week out. Rather, the odd dud is all part of the experience.

So, if this book gives you the confidence to ‘have a go’ then I will have achieved all I could have hoped for. If you try some of the wines I mention, you’ll get a feel for the style of wines that float my boat. They’re gutsy, spunky wines with a

lot of character: wines that tell stories, that make me happy and help create new memories. I hope what follows makes you smile, and that the wines you discover will help carry you through life’s dreadful lows and beautiful highs, and all the stuff in between.

First Glass

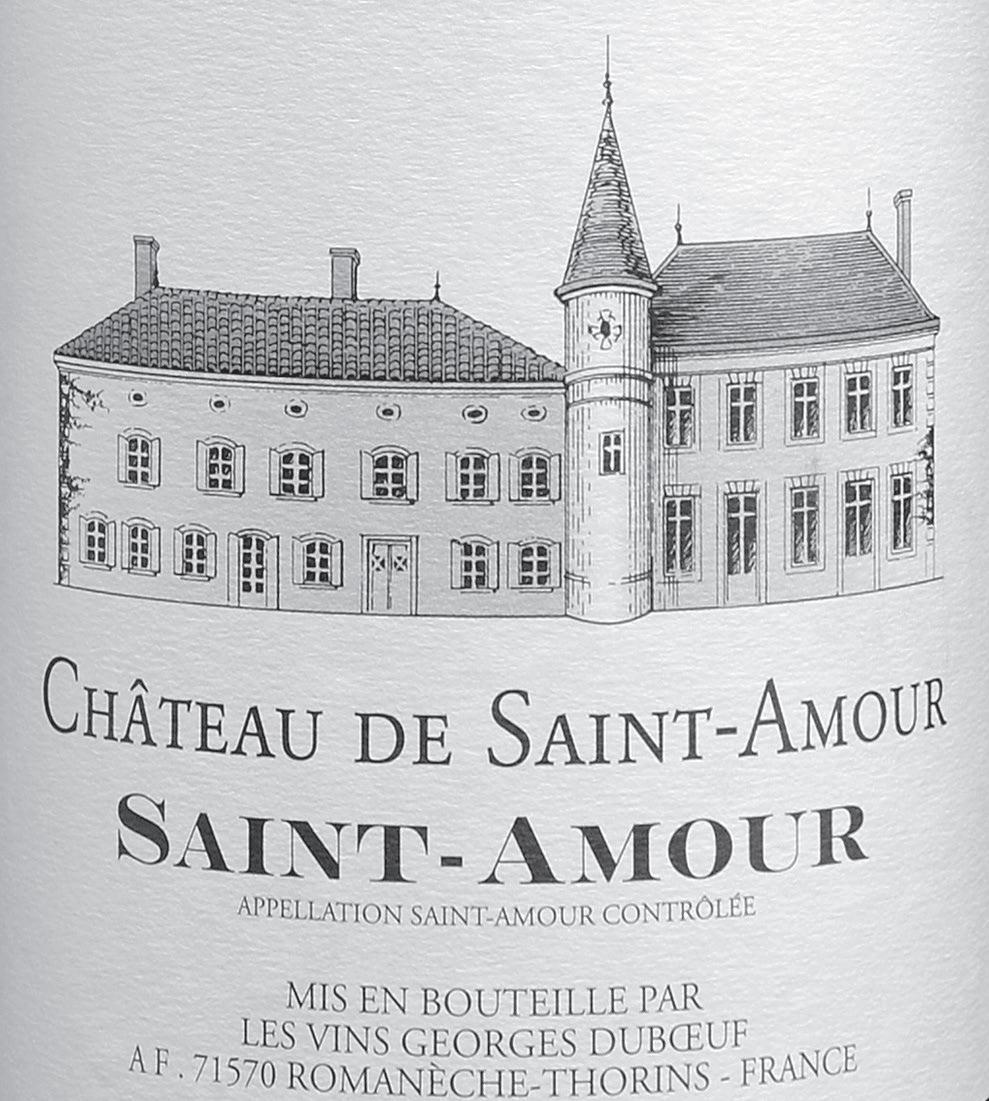

Hero bottle: Saint-Amour, Château de Saint-Amour, Beaujolais, France

The November sun streamed through the windows of the Eton Wine Bar, catching the specks of dust that swirled above the old reclaimed church pews we used as benches. Two hours earlier, my dad Bill and my uncle Mick had roared up in their mud-spattered Saab Turbo, triumphantly unloading cases of the precious red wine they’d just raced back home with from France. Etched on their faces was a blend of exhaustion and elation, their clothes still creased from the overnight dash. Le Beaujolais Nouveau est arrivé!

Now they’d lined the tall glistening- green bottles up on the bar, labels still damp from the cellars, and the lunchtime queue outside on Eton High Street buzzed with anticipation – office workers who’d escaped early, local wine merchants eager to compare notes, and regular customers who’d been coming to this annual event for years.

Then, at last, it was time to open the doors, and the throng filled the bar. Their French berets askew, Dad and Uncle Mick drew the first corks with theatrical flourish and that distinctive aroma of young wine filled the air – all crushed raspberries and youthful exuberance. Mum and Aunty Lin buzzed around with laden charcuterie boards: rough country pâtés, fat-marbled saucisson and wedges of pungent cheese.

With his first pour, Dad’s eyes twinkled, while Uncle Mick, ever the showman, regaled everyone with tales of their mad race through Beaujolais backroads.

As the wines flowed, the tales grew taller, Uncle Mick and Dad got squiffier by the glass, their rich laughter like music bouncing off the walls punctuated now and then by the gentle clinking of bottles and the kissing of glasses. This wasn’t just another mid-week lunch – it was Christmas come a whole month early – a celebration of tradition, adventure, and the simple pleasure of being among the first to taste the new wine of that year.

The third Thursday of November each year, Beaujolais Nouveau day, is one of my favourite dates on the calendar. It brings with it a very special type of joy. On that day, there’s a carnival atmosphere in the province of Beaujolais because come midnight, wine growers across the region can release France’s very first wine produced from that same year’s récoltes (harvests). A vin de primeur, or early wine, this cheeky, light, violet-like red is fermented and bottled mere months after the grapes were still hanging on the vines. As such, ‘serious’ winelovers dismiss Beaujolais Nouveau as an uncouth upstart of a wine – basic and unprofound, brash and over-hyped – but, to my mind, they’re missing the point entirely. To understand Beaujolais is to understand that simplicity, when done well, can also be profound.

There’s something undeniably charming about the exuberant grape-juice freshness of a Beaujolais Nouveau. Light in body, bursting with fruity scents – crushed strawberry, raspberry, cherry and redcurrant – it is a red wine that is often served at a slight chill (around 12– 14°C) to bring out its vitality. Uncle Mick once described it as ‘tasting like someone

had run a raspberry through a photocopier’; but Dad put it best, I think: ‘It’s the only wine that tastes better after your fourth glass than your first.’ It’s summer pudding in a glass, the last taste of sun as the autumn leaves fall and the air chills for the first time. A glass of a cheeky, fruity young Beaujolais refreshes both body and soul; low in tannin and gloriously gluggable, it reminds me that wine, at its heart, is made to bring pleasure.

These are wines for friendships and long lunches, for spring afternoons and autumn evenings. They pair as happily with a slice of peppery saucisson sec as they do with a carefully prepared coq au vin. Above all, they remind us that wine should bring joy to the table, make us want to reach for another glass, and make us slow down and take time to savour not just the food and drink on the table, but the moment itself. Beaujolais, like the green rolling hills it hails from, has a gentle quality to it that makes you want to linger over a glass or two just that little bit longer, so stay with me here. There’s something deeply comforting about this wine, in fact: like pulling on a well- worn cashmere sweater on the first cold day of autumn. And so, Beaujolais has held a special place in our family’s heart as long as I’ve been alive. In fact, for us it was never just about the wine, it was a culture.

When they started the business, Dad and Mick were both youngsters. Mick, in his late twenties, was the younger of the two brothers by eight years, but they were so alike they could have been identical twins. A pair of 5'10", athletically built bon vivants, their symmetrical Mediterranean complexions and easy smiles made them indistinguishable to firsttime customers. They moved through the wine bar with

synchronised swagger, both blessed with that natural charm that made everyone feel like an old friend. Dark- eyed and mischievous, they’d finish each other’s sentences and share knowing looks across the room, their laughter as infectious as it was genuine.

Dad had been working for the old family firm, Gilbeys, which had joined others to form Independent Distillers and Vintners ( IDV ), which then became Grand Metropolitan. Sadly, as with many old family firms, Gilbeys didn’t have a particularly strong HR department. Employ the eldest son, no matter how stupid he is, and give him way more responsibility than he can manage . . . seemed to be the policy. By the time my dad (not the eldest) went to work in what was now a huge conglomerate it was, what sounded to me, like a viper’s nest and a pretty unhappy one at that. And so, when one day Dad received a letter from the firm, in which they addressed him as a number, he stuck two fingers up at their job, bought a set of chef whites and, together with his brother Mick, set up the Eton Wine Bar. Mick was wine guy and businessman and, as the chef whites allude to, Dad did the cheffing. My mum and Aunty Lin kept the wheels turning, making sure the staff and customers were happy, and the wine bar always welcoming.

The Gilbey brothers’ duplicated charm but it was Mum who was the soul of the place. While Dad commanded the kitchen in his chef whites, it was Mum’s cooking that we all craved; her intuitive understanding of flavour was born from pure love rather than any classical training. She knew every regular’s story, held their secrets, shared their joys. She could often be found in quiet corners of the bar, consoling a disconsolate staff member, celebrating a new

baby, or simply listening with that gentle smile that made everyone feel safe. Her warmth could melt the frost of a December morning.

They were an ideal partnership, though, my parents: Dad’s exuberant energy balanced by Mum’s nurturing presence. The wine bar was their stage, but their real magic was in creating a space where everyone felt like family. Even now, if I close my eyes, I can see them there: Dad in the kitchen in his whites, a spoon in the filling for his chicken and tarragon pie, and Mum downstairs making sure every glass was filled and every heart full.

For the four of them at the wine bar, Beaujolais was at the beating heart of it all. Their wine list read like a love letter to the region and lots of it ended up in Dad’s dishes. His food was honest and rustic with a big dollop of generosity and joy, and he had an innate understanding of what flavours and ingredients worked with Beaujolais. His coq au vin, for example, had a sauce so rich it could only have been made using more vin than coq. And as for his beef cheek recipe, it guzzled more Morgon than was ever sent out to the dining room, and that’s one of the more expensive wines from the region. I dread to think what the profit and loss sheet looked like!

It was therefore only fitting that Beaujolais played host to my first glass of wine. No longer a sip of Mum’s on a Sunday lunch. It was a glass poured just for me, for health reasons of course – my parents were firm advocates of the health benefits of red wine in moderation. I was going to grow big and strong.

It was July 1988. I was a gangly sixteen-year- old showing too much interest in alcohol and cigarettes and, by Uncle

Mick and Dad’s reckoning, I’d come of age and needed some fine tuning. So too did Mick’s son, my cousin Henry, who was a year younger than me and, quite probably, Iron Maiden’s number one fan. We were on a similar trajectory. The two of us, both eldest sons, were to join our dads on their annual ‘buying’ trip.

Dawn arrived with a firm nudge from Mum at 4 a.m., Henry and I sprawled in our respective beds – as an overnight guest, Henry’s makeshift futon was hardly worthy of such a name – watching her gathering our clothes through bleary teenage eyes. Henry clutching his prized Walkman and heavy metal cassettes, we stumbled down to the kitchen to the sound of the spitting coffee machine and the smell of the fresh brew. Dad and Uncle Mick had had a few glasses the night before in excitement at their forthcoming trip and yet, even slightly hungover at 4 a.m., they still looked very much ready for the challenge ahead. Dad with his customary lumberjack look – unshaven in a thick checked shirt and threadbare brown cords – his standard uniform when not in his chef whites, whilst Mick, always a bit smarter, had donned his light-beige chinos and crisp blue shirt.

Then, as Dad and Mick continued to plot our route, Mum shepherded us all into the old battle- scarred Citroën CX , our family-car-cum-wine-delivery-vehicle, whose boot could comfortably fit ten cases of wine along with a French cashand-carry haul filling every available void. I can remember the smell of that car still today; of the wine bar, of Dad’s lasagne, and of the odd accidental spillage of red wine leftovers. It was even home to some handy emergency cooking ingredients – its very own (slightly pongy) mushroom colony growing in

the passenger footwell. ‘It adds character,’ Dad insisted. We were heading to Beaujolais, first class.

In 1988, Beaujolais Nouveau was still the region’s calling card. We, however, were bound for greater things: the home of JeanMichel Roux, a pioneer of mobile bottling, big wig of Beaujolais, and a great pal of Uncle Mick’s. (All will become clear, but for quality wine this bottling method was, and still is, a big thing in France. If you see the words ‘Mis en Bouteille au Domaine / Château/Propriété ’ printed either on the cork or the wine label, it’s generally a sign of excellence. It means that the wine grower hasn’t sent it away to the big local co-op for the final touches and bottling; instead it’s all been done on- site under their watchful eye. So, Jean-Michel, genius as he was, and still is, put the bottling line on the back of a truck and drove it to the different vineyards to provide this ‘mis en bouteille ’ service to all those who couldn’t afford to buy their own bottling line. And he got a lot of trucks in the end. Very clever!)

The small historical province of Beaujolais nestles in that sweet spot between Burgundy and the Rhône Valley. Just thirty-five miles north of Lyon, it stretches like a tipsy grin across eastern France, and for me, it is perhaps France’s most disarmingly authentic region – where gnarly old vines cling to granite slopes and village bistros pay homage to the late Anthony Bourdain. On misty mornings, when the sunlight begins to stream through the café windows, carafes of local wine sit naturally alongside a plate of jambon persillé de Bourgogne – rustic chunks of salty ham jellied in aspic and garnished with freshly- chopped parsley – or a simple pâté de campagne with cornichons. The Beaujolais wine has an effortless way of making even the most modest meal feel like a celebration.

In the villages that dot this landscape, weathered stone houses overlook vineyards that have seen millennia pass by. The main grape variety you’ll find here is the Gamay, which grows pretty much exclusively in Beaujolais. Other regions and countries try it but only here on these granite and schist slopes does the Gamay reach heights of magically unctuous, teeth-staining charm. And through its wines it tells stories of these mineral-rich soils it grows in.

Of course, there has always been a lot more to Beaujolais than simply the aforementioned Nouveaux. In fact, for years, Nouveaux has tainted the reputation of this wine region whose red wines are often beautifully made, food friendly and sometimes really quite fine. There are actually three quality levels in Beaujolais that are governed by the French wine laws known officially as the ‘Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée ’ (AOC ). (For a French wine to be granted a prized AOC certification, the producer must follow strict rules in order to ensure consistency and tradition – precisely how and where the grapes are grown, and how the wine is made.)

I like to think of the gamut of the region’s wines (mostly red) as like the attendees of a French family party. First, you have the young party kids – the AC Beaujolais, which includes the youngest of the lot, Beaujolais Nouveaux; as described earlier, these are the least complex wines, with Nouveau being the baby, the first wine that France gives us every year.

Then, on the next rung on the ladder we have the groovy older cousins – the AC Beaujolais-Villages. Admittedly, a very confusing name because this appellation encompasses no specific village. Rather, it covers the good but not great vineyards where Gamay gives us more character and depth than in its simple, often boisterous siblings. So, basically, these Beaujolais-Villages wines are a bit like a Nouveau if it went to finishing school – it has learned to tie its shoe laces but still has bags of youthful exuberance.

So, that’s two of the quality levels. The step up from that are the Crus (the classified growths) of Beaujolais. These are the villages and areas officially recognised for producing wines of exceptional quality and in Beaujolais there are ten of them. That’s ten top- ranked wine- producing villages, each with their own AC , each producing their own unique slant to Beaujolais red wine made from the Gamay grape, and each allowed to put their village name on the label – Fleurie, for example – and they’re the more serious party guests, the slightly snooty aunts and uncles, who insist on everyone using their full names. These wines hail from vineyards growing along a 24- kilometre strip of granite hills in the north of the region with each Cru offering an utterly charming, superior red wine, all made from the Gamay grape, each with an underlying typicity