Michiko Aoyama

Michiko Aoyama

Translated by Takami

Nieda

Also by Michiko Aoyama

What You Are Looking For Is in the Library

Takami Nieda

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London sw11 7bw penguin.co.uk

First published in Great Britain in 2025 by Doubleday an imprint of Transworld Publishers First published in Japan by Kobunsha Co. Ltd.

This English-language edition published by arrangement with Kobunsha Co. Ltd. through The English Agency (Japan) Ltd. and New River Literary Ltd. All rights reserved.

Copyright © Michiko Aoyama 2023 English translation copyright © Takami Nieda 2025 Illustrations by Rohan Eason

The moral right of the author has been asserted

This book is a work of fiction and, except in the case of historical fact, any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset in 11.5/15.5pt Dante MT Std by Six Red Marbles UK, Thetford, Norfolk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9781529949766

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

Iturned the 6 into an 8.

And the 1 into a 9.

In a matter of seconds, my world was transformed. I clicked the cap back on the red felt-tip pen.

The 61 I scored on my English test was now an 89. This rewritten reality seemed much more suited to who I really was. It was all good, I told myself.

After all, there was no way I could be this stupid.

Last year, during the summer of my third year in junior high school, my father announced that he was buying a condominium.

‘In a brand-new building. Isn’t that great, Kanato?’ His voice sounded higher than usual and filled with pride as he shared the news at dinner, beer foam

glistening on his lip. It had always been a dream of my father’s, who had lived for years in employee housing, to own a home of his own.

He told us the name of the nearest train station, about an hour from our current home and closer to Tokyo. My mother added that an electronicsmanufacturing factory would be demolished for a new five-storey condominium building.

My parents decided on a first-floor unit with a yard – a rarity for a condo, which was a plus. Having a garden where my father could get his hands dirty was essential, and they’d been looking at older houses for this reason, when they first discovered this property. It was close to the train station and with a supermarket and plenty of restaurants near by, checking off both my parents’ budget and location requirements. They couldn’t be happier.

Advance Hill. Construction of this ostentatiously named condominium was scheduled for completion in March, so my parents set a date to move after my junior high school graduation.

Until then, I attended a public school in a quiet suburb. Not to sound immodest, but I was a top student.

Life in junior high was lax. Tepid. If I’m being honest, I don’t recall ever studying. If I paid

attention in class, I could flip through the textbook before a test and guess what would be on it. All I had to do was submit my worksheets on time, and I had a row of A’s on my report card.

Watching students passing around notes or sleeping with their mouths open during class, I couldn’t understand why they would be jealous that I was ‘smart’. It was no wonder their grades were horrible.

With the move closer to Tokyo, I decided to apply to a preparatory high school in the city.

Other than me, no one else at my junior high had applied to that school. Seeing my mother’s satisfied smile when my homeroom teacher mentioned I should be able to qualify for recommendationbased admission made me happy, too. I passed the entrance exam without much difficulty, freeing me from that particular worry before the year ended.

I quit the cram school I’d been attending since grade school and spent the year-end holidays reading manga and playing video games. Busy shopping for curtains and furniture, my parents made no comment on how much I was playing.

As graduation approached, the homeroom teacher said something about how I would miss my old friends, but I didn’t particularly feel that way. I had

classmates that I got on with, but I wouldn’t say they were friends that I could open up to, and I never felt like I belonged.

Since I didn’t have anyone to miss, what I felt, if anything, was free.

A new home, a new life. I entered high school with high hopes, fully expecting to find a friend who I could truly connect with.

As soon as the term began, however, I realized I didn’t fit into any cliques.

The popular crowd was too intimidating, the guys who were always arguing a little too loudly were unapproachable, the nerds buried in their study-aid books were hard to talk to. In retrospect, my classmates from junior high school were much easier to talk to.

But more than anything, it was the midterm exams that delivered the biggest blow.

For starters, each test had too many problems, so I couldn’t finish within the allotted time. Not only was it tricky to predict what would appear on the test, but some questions weren’t even covered in class. The teacher said anything considered part of the general education requirements was fair game, or something like that. When the exam period was over, all my tests came back with

low scores. My pride was in tatters. A few days later, we received a slip of paper listing students’ rankings.

Thirty-fifth out of forty-two students.

Since I had never received a ranking lower than third, I was shocked.

Something’s wrong, I thought. I can’t possibly be this stupid.

There was no way I could show the results to my mother. I played innocent for as long as I could until she finally asked, ‘How did you do on the midterms?’ I showed her my exam sheets, making sure to leave out any mention of student rankings.

As she looked at the scores, the crease between her brows grew deeper. To keep myself from falling into that furrow, I hastily said, ‘The average scores were low.’

The crease on her face relaxed slightly.

‘The exams were incredibly hard. Everyone was struggling.’

That was a lie. The only exam that I’d managed to score above average on was in English, my best subject.

‘Eh, sounds about right for your first exams in high school,’ my father intervened. He then

mentioned buying some fertilizer at the hardware store, and thanks to him, my mother handed back the exam sheets and started talking to him.

It wasn’t so much that he had sent me a lifeboat as that he didn’t care. My father never took an interest in me, much less my grades, and despite his ever-present smile, he never praised me for anything. Still, I was grateful to him for changing the subject.

I told myself I’d do better on the final exams, but all my motivation had vanished.

I found myself in an awful predicament. The truth was that I’d sensed the difference in my skill level between my classmates and me during class. The gap was so wide that it felt impossible to catch up.

The pace of the lessons was fast, and I frequently couldn’t answer when the teacher called on me.

Growing impatient with my silence, the teacher called on another student, and when that student answered correctly, I wanted to crawl into a hole and die. It seemed simply paying attention in class, like I had in junior high school, wasn’t cutting it any more.

As I struggled to concentrate, my final exams came and went. Now, two days after finishing them, I had come out of the room completely

overwhelmed. I felt like I had done even worse than before. Everyone else seemed like a genius. They all had breezy looks on their faces.

The few days’ wait for the student rankings to come out was more nerve-racking than the wait for the high school acceptance.

Yesterday, we received the results of the English exam.

A 61. The average was 62. I had failed to exceed the average in my best subject.

More speechless than disappointed, I was numbed.

As soon as I got home, my mother asked when I was getting my tests back, and I panicked.

That was the moment I went back to my room and picked up the red pen.

And turned the 6 into an 8.

And the 1 into a 9.

‘I got my English test back,’ I said now, and showed her the score.

The 89 was displayed prominently on the answer sheet.

‘The average was sixty-two.’ My voice was confident because it wasn’t a lie.

Narrowing her eyes, she replied, ‘Good for you, Kanato! You must have tried very hard.’

‘Uh, yeah,’ I answered.

The inside of my mouth tingled like I’d swallowed

some bitter medicine. Inwardly, I was screaming. Why? How?

How did I get so dumb?

The next day, when I arrived at my train stop after school, I couldn’t bring myself to go straight home, so I decided to take a detour.

I turned off the main road on to a backstreet and into a residential neighbourhood. Amid the rows of houses stood a well-worn building with a store occupying the first floor. The words ‘Sunrise Cleaning’ were outlined against the red overhang. There was a soda vending machine out front; fluorescent lights shone through the glass storefront.

I carried on walking until I reached a cluster of run-down beige-looking apartment complexes. It was late evening, but there were still several futons hanging over balcony railings to dry.

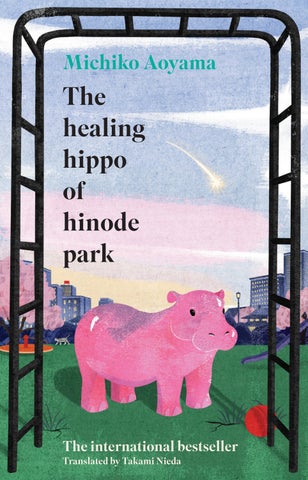

I walked along the narrow promenade until I got to a small playground nestled among the apartments. At the entrance stood a stone slab with the words ‘Hinode Park’ engraved into it.

It was a small, gravelled playground, fitted out with the usual items you might expect to find in a park: a set of swings, a slide, a sandbox and benches.

No one else was around except for me. As I

stepped into the playground to rest on a bench, an animal-shaped figure in the corner caught my eye.

A hippopotamus.

It was one of those stationary animal rides you just sat on. The orange paint, browning in places, was starting to peel off. The exposed concrete underneath created a mottled appearance, all quite normal for a hippo. Its oval-shaped eyes were turned slightly upward, the black of its pupils also peeling in spots, giving it a teary-eyed look like something out of a manga. A smile spread across its face and curled up at the corners. The upturned nostrils perched atop two mounds lent the hippo a ridiculously carefree expression.

I approached it to get a closer look. With a marker, someone had scribbled ‘STUPID’ on the back of its head. Calling a hippo stupid for being slow-moving – what a cheap shot! Seeing such a violent scrawl broke my heart.

And yet, the hippo was smiling. Maybe it couldn’t see the graffiti because it was written on the back of its head. Maybe the hippo didn’t know it was being slandered.

With a deep sigh, I tried to rub out the word with my fingers. The letters, likely written in permanent marker, weren’t about to come out so easily.

I took out a pencil case from my knapsack and

tried rubbing the marker out with an eraser. It was no use. My efforts produced only eraser crumbs as the word stubbornly remained emblazoned on the hippo.

This filled me with an urge to get rid of the graffiti by any means necessary. I couldn’t help but see myself as the hippo, helpless to do anything about the ‘stupid’ label he was stuck with.

I came up with the idea of painting over it in a similar colour.

I should have some orange lacquer paint that I’d used to colour a plastic model when I was in junior high back home.

‘I’ll bring it tomorrow, okay?’ I said out loud to the hippo.

The stumpy hippo looked up at me, teary-eyed and smiling.

The following day, as soon as school ended, I rushed straight for the park, a bottle of lacquer paint stuck in my knapsack.

I stepped inside the park to find a girl in a school uniform pumping her legs on a swing. Noting the blue ribbon waving in front of her white blouse, I realized she was from my school.

She was smiling and gazing into the distance, her cheeks flushed. Her face felt familiar.

That was it. She was a classmate – Shizukuda-san, I think it was. I’d never spoken to her before and couldn’t remember her first name. But her naturally curly hair and her loud, husky voice had stuck in my mind.

As I turned back towards the gate, Shizukuda-san looked over and caught my eye. For some reason, she smiled at me as if we’d known each other for ages.

My heart skipped a beat. I dipped my head in greeting.

She brought the swing to a stop. ‘You’re Kanato Miyahara!’

My heart skipped again. She knew my full name! ‘What are you doing here? Do you live in the neighbourhood?’

‘Uh, yeah,’ I said. ‘The condominiums called Advance Hill.’

‘I know that place! The new building on the hill. Oh, wow.’

She hopped off the swing and came towards me. I unthinkingly moved towards her too.

‘I’ve been living here since I was a kid. Building six.’

Her building faced the park. Struggling to keep the conversation going, I asked, ‘Do you like the swings?’

She looked into the distance again and answered seriously, ‘Like? More like it helps me to decompress and recharge. When everything feels like a lot sometimes.’

Decompress and recharge?

As I struggled to respond, Shizukuda-san turned towards the corner of the playground.

‘Kabahiko!’ she said, as if she were calling to a dog or cat, and walked up to the hippo.

‘Kabahiko?’ I parroted back, and Shizukuda-san nodded.

‘Yep. The name of this guy here.’

She turned to face me. ‘Kabahiko is an amazing hippo. People say that if you touch the area of his body that you want to make better on yours, he’ll provide a cure.’

I was stunned. Who knew that a miserablelooking hippo had the power to bestow such benefits?

Putting up a finger, she added, ‘They call him Healing Kabahiko.’

‘Healing Kabahiko?’

‘Get it?’ she said. ‘Because Kaba-hiko sounds like hippo.’

I huffed, not because it was funny but because all the tension seemed to drain out of me.

Shizukuda- san then explained, ‘It’s this old rumour from round here. Something I grew up hearing about. The lady at Sunrise Cleaning said she patted Kabahiko’s back, and it cured her herniated disc.’

Sunrise Cleaning. I remembered passing it on the way here.

I quickly scanned my surroundings. At dusk, there was no one else inside the shadowy playground. Perhaps noticing the suspicious look on my face, Shizukuda-san turned her head.

‘Well, not that it’s all over the news or anything. There’s no scientific basis for it. I mean, it’s just a boring hippo in this boring park.’

She was right. Both the subject and location weren’t buzzworthy enough for such a rumour to go viral. Besides, the park didn’t have any other attractions that would make anyone want to come here.

Still, it was good to know.

I wanted to be cured of my stupidity. I wanted people to tell me that I was smart again.

Shizukuda-san crouched in front of Kabahiko. The hippo seemed to hold a special meaning for her, who’d lived here for years.

‘Please make me beautiful,’ she prayed, touching Kabahiko’s face.

‘Does it work on those kinds of things, too?’ I asked, suppressing the burning question in my heart: Isn’t that more a wish than a healing?

Seeming to read my mind, she stood up with her hands balled into fists. ‘I was adorable when I was little, you know. When I was four, a scout stopped my mother and me on the street and asked if I wanted to go into modelling.’

‘Okay . . .’

‘It’s true! Even though I look like this now . . .’

She cast her eyes down and pouted.

Like this ? Now that I had a chance to talk to her, I thought she was cute.

I made sure to tuck that thought away in a corner of my heart where she couldn’t read it. She gave Kabahiko’s face a good rub.

‘Please, Kabahiko! Heal my face!’

Trying to match her energy, I put a hand on Kabahiko’s head.

‘Please, Kabahiko! Heal my brain!’

‘Your brain?’

Shizukuda-san chuckled, and the mood between us relaxed. I felt a sense of relief that I hadn’t experienced in a while.

Like tangled threads unravelling, I began to speak my thoughts.

‘I used to be a pretty good student when I was in junior high. So I was shocked that I bombed the midterm exams. When the final exams were just as hard, I lost all confidence. There was so much covered on the geography test.’

‘I’m horrible at geography,’ Shizukuda-san piped up. ‘I’m more of a science person, if anything. When I found out at the entrance ceremony that our homeroom teacher would be Mr Yashiro, the geography teacher, I almost cried,’ she said, making a face.

Finally, I found a classmate with whom I could have a frank conversation. Although, bonding over our lack of academic skills wasn’t exactly the ideal scenario.

‘But you’re really good in English, Miyahara-kun! Your pronunciation is excellent.’

Well, yeah, but . . .

‘But I didn’t even rank in the top five on the midterms. I used to be first in junior high.’

The instant the words left my mouth, I wanted to run away in shame.

What a colossally cocky thing to say.

I was talking like I’d ranked sixth or seventh in

the class. I was being pathetic, trying to impress Shizukuda-san by pretending to be a top student.

I braced myself, worried that she might be put off by what I’d said, but she started to cackle, ‘I’m not even in the top ten!’

She climbed on to Kabahiko’s back. Her legs sticking out from her skirt were so blindingly pale that I had to look away.

Shizukuda-san fiddled with her hair, muttering to herself, ‘I think rankings are cruel. If you ask fortytwo students to do the same thing at once, someone is going to come in forty-second. There’s always going to be a forty-second. You can’t just make that last spot disappear.’

When I found out I was thirty-fifth, I had thought that there were only seven students behind me. But after a fleeting moment, I had thought, there were still seven students behind me.

There was no telling what would happen next time. I might easily find myself sitting in the fortysecond spot you couldn’t make go away.

Shizukuda-san continued, ‘Rankings are only important for people confined inside their tiny world.’

The way she said only stung my chest.

‘An Olympic runner is already awesome just for being at the Olympics, but winning at the Games

doesn’t necessarily make you the best runner in the world – because somewhere in a secluded corner of the world so deep in the mountains you can’t even get a signal, there could be a boy that runs faster than anyone.’

‘What country is that?’ I asked.

‘I don’t know. I’m just imagining. That boy loves to run, like really, and he couldn’t care less about competing or about accolades or fame.’

I tried to imagine the boy she described. He was running through the fields and through mountains, half-naked and barefoot. I felt certain that a fast boy like that surely existed.

He ran and ran to his heart’s content, blissfully unaware that he was the fastest human in the world, never seeking such a title in the first place.

And then, I was reminded of a certain character in a popular manga.

The comic, which had also been adapted into an anime, was called Black Manhole. It was a story about a monster living in the sewer system, which also featured a character named Terra, who was superfast. He ran at an incredible speed, without competing against anyone, completely absorbed in the act of running itself.

‘He sounds like Terra,’ I said. ‘From Bura-man.’

‘Bura-man ? Oh, you mean Black Manhole. I know