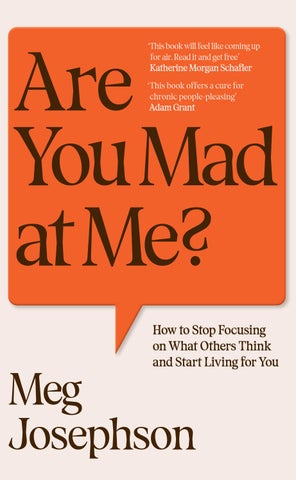

This book offers a cure for chronic people-pleasing’ Adam Grant ‘ ‘

This book will feel like coming up for air. Read it and get free’

Katherine Morgan Schafler

This book offers a cure for chronic people-pleasing’ Adam Grant ‘ ‘

This book will feel like coming up for air. Read it and get free’

Katherine Morgan Schafler

How to Stop

How to Stop on What Others Think on Others Think and Start Living for You and Start Living for You

Meg Josephson, LCSW, is a licensed psychotherapist. In her private practice, she specialises in trauma-informed care through a compassion-focused lens. She holds a Master of Social Work from Columbia University, and is a certified meditation teacher through the Nalanda Institute. Meg also shares accessible insights via her social media platforms, reaching over five hundred thousand followers.

Square Peg, an imprint of Vintage, is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies

Vintage, Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW

penguin.co.uk/vintage global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published in Great Britain by Square Peg in 2025

First published in the United States of America by Gallery Books, Simon & Schuster, LLC in 2025

Copyright © Margaret Josephson 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted Interior design by Matthew Ryan

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

HB ISBN 9781529949612

TPB ISBN 9781529949629

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

For those who have kept the peace but lost themselves

As a therapist, protecting my clients and honoring the intimacy of the therapeutic relationship is my greatest priority. In these pages, I’ve created vignettes of individuals who reflect not actual clients but my experiences with them.

The stories contained herein are not about specific individuals but are a tapestry of shared experiences, inspired by the complexities of relationships, the impact of complex trauma, and the universal longing for connection and healing. My highest intention is to honor the stories and emotions of many while preserving the anonymity of all.

“Why do I always think people are mad at me?” I ask my therapist.

It’s our first session together on a sticky, hot day in New York City. Her sage-green office is tucked between Union Square and Chelsea, and the shrill sound of passing sirens drifts into the room like a breeze. I’m twenty years old, interning at a lifestyle magazine for the summer in between my sophomore and junior years of college. I’ve saved up enough money to afford five to seven sessions with her over the summer, so I say a silent prayer to no one that she’ll fi x me up quickly.

In response to my initial question, she nods slowly and breathes deeply, waiting for me to say more while I wait for her to say anything. She adjusts her rectangular red-framed glasses and recrosses her legs, and my gaze settles on the painting above her chair. I squint my eyes and tilt my head as I try to decide whether it’s a painting of a flower or a vagina.

At the end of our fifty minutes together, after providing her with some background on my life thus far, I walk out of her office with tearstained cheeks and a recommendation for a book on adult daughters of an alcoholic parent. Weird, but okay.

I had hoped that said therapist would tell me what was “wrong” with me and provide me with a three-step solution, a goodie bag, and a 2.0 version of myself. Instead, she spent most of the session

asking me about my childhood, and in our subsequent sessions together I was gently brought to the realization that while I was no longer living at home, in some ways it felt like I was still there. I was no longer anticipating my dad’s mood swings, but I was now anticipating getting fired anytime my boss messaged me. I was no longer analyzing the cadence of my dad’s speech to see if he had been drinking, but I was now analyzing what it could mean when my friend texted with a period at the end of the sentence instead of an exclamation point. I no longer needed to be “perfect” and “good” to keep the peace at home, but I realized that I still felt terrified to be seen as anything but perfect and good now.

This hypervigilance—this unconscious sense of constantly being on high alert, on guard—was the thread weaving through both my childhood and my adulthood. It was during this summer that I finally understood that my present-day fears were not just phobias to overcome; in fact, they served a crucial purpose: they had kept my past self safe. What I viewed as self-sabotage had been self-protection.

After that summer I was confronted with the understanding that perhaps healing isn’t a checkbox item but an uncomfortable, messy process of looking inward. Huh. But I was motivated. If there was one thing I was sure of, it was that I didn’t want to live in a state of deep fear anymore. I felt like I was split in two: the younger part of me that was living in fear, and the wiser “parent” part of me that knew a better, more peaceful existence was possible. I just didn’t know where to start.

So many people, especially women, struggle constantly with the notion that people are mad at them. We fearfully say, “Are you mad at me?” to our partners when they’re in a bad mood, to our best friends when they don’t text back, to our colleagues who didn’t say hi to us when we passed each other walking out of the bathroom. Or maybe we don’t ask and instead just silently ruminate about it when we’re in the shower until our hands are pruney and when we’re lying alert in bed at one a.m., chest tight, until we’re too exhausted to think about it anymore.

Today, it may seem odd that we worry so much about how others perceive us given that we’re in constant communication with one another. But it’s precisely because of this endless receiving and giving of external validation and reassurance—texting, hearting others’ texts, liking their posts, FaceTiming, DMing videos—that we are sent into tailspins of insecurity. When our bodies are so used to that intense amount of communication and then it’s reduced in any way, this can easily send the part of ourselves that is focused on survival into a spiral. There are so many ways to tell someone you’re thinking of them, and because of that, there are also so many opportunities to feel forgotten.

When I went back to school that fall, I got a pretty bad concussion after a drunk guy at a Halloween party fell against me, knocking his forehead into mine with an (almost) impressive amount of momentum. Doctor’s orders were to take time off from classes, not look at screens, and rest in the darkness as much as possible. Whether I realized it then or not, this abrupt pause propelled me

into a meditation practice and a spiritual practice that put me on a path back toward myself. It was during these months of recovery that I was forced, whether by that guy’s rock-hard forehead or by the universe, to stop numbing myself, stop drinking, stop distracting myself. I had to stay with the emotions, memories, and wounds that I had ignored for so long, that had been tucked away into little dusty corners of my body and mind.

This is where I’m supposed to tell you exactly how I “healed” in a neat, buttoned-up paragraph. But my emotional healing was slow and subtle, and it’s still ongoing. As the years passed, I didn’t even realize how much I had changed until I looked back and noticed how different I felt in situations that had used to spark so much tension. Five minutes of meditation had once felt like an eternity when I was agitated by the discomfort of my inner world. And then one day I realized that I could sit for an hour with genuine ease. One month of no drinking turned into seven years. Something that would’ve once sent me into an overthinking spiral now seemed less overwhelming. I was able to experience a challenging emotion, identify the emotion, and realize that I didn’t have to change it; I just had to alter my reaction to it.

After college, I felt an undeniable pull to support other people in their healing, to integrate the denser, trauma-based work with mindfulness-based practices. I had seen firsthand the benefits of integrating those two worlds. I went on to graduate school at Columbia University, where I received my master’s in social work with a concentration in clinical practice while continuing to deepen my

spiritual practice and study Buddhism. When I finished my graduate program and started practicing as a full-time therapist, my caseload quickly filled up, mostly with women struggling with anxiety, relationships, life purpose, self-confidence—and, most of all, people-pleasing.

On a foggy Tuesday in San Francisco (life update: I had moved across the country), I had a session with a client who talked about how she would head home after a social event anxiously replaying in her mind all the cringey stuff she had said. She’d convince herself that everyone hated her while swallowing the urge to text her friend an apology for something that she couldn’t even put her finger on.

“Why do I always think people are mad at me?”

Here I was, now in the therapist’s seat, my twenty-year-old college self mirrored back at me, being asked the same question I had once posed to my first therapist.

Later that day, I posted a video on social media in which I said, “Hey, you are not in trouble; you’re okay. They aren’t secretly mad at you. Your mind is lying to you because it’s scared. I know you may have this fear that you’re secretly a bad person and it’s just a matter of time before everyone finds out, but you’re actually safe.”

Within hours, it blew up across platforms on social media, with thousands of people commenting things like, “Okay, why am I crying?”; “This was . . . oddly specific but true”; and “Are you inside my mind right now?”

I continued to post videos about this topic, this feeling, and every time, without fail, they’d have the same resonance with folks around the globe—and I continued to see clients come into my office with the same inner experience that was so familiar to me on a visceral level.

And so I wrote this book because it’s one that I once desperately needed and one that I believe many people need.

There are lots of books out there about people-pleasing and codependency, but what’s often missing is the true root of these behaviors, what precedes the need to be a people pleaser and abandon ourselves in the first place, and the context of why we do it. People-pleasing is the behavior we engage in when we fear that we’re disappointing someone, that we’re in trouble, that we feel unsafe in some way. It’s the behavior that falsely soothes the queasy feeling that we’ve done something wrong. We can’t do the inner work if we can’t even pay attention to what’s going on internally because we’re so focused on looking outward at other people’s perceptions and reactions. This book speaks to the root of the pattern—the fawn response. That is where true healing takes place.

Women in particular are conditioned to overextend, overexplain, overapologize. We’re caretakers. Nurturers. Peacekeepers. We’re taught to be good girls, cool girls, to agree with everything and everyone, and to give Uncle Richard a big hug, for goodness’ sake, even if he makes us wildly uncomfortable. We’re taught to not be too much or want too much, so we learn to get used to being un-

satisfied with our lives. We’re taught to meet everyone else’s needs before our own, and along the way we lose the opportunity to get to know who we really are, what we need, what we like and prefer. This is especially true for people who grew up in dysfunctional, high-tension, high-conflict, or emotionally neglectful home environments where Are they mad at me? was the exact internal question that made them feel safe. There’s this popular narrative that young people, especially millennials, love to blame their parents for every negative aspect of their existence. But this work isn’t about blaming; it’s about finally looking at wounds that have been begging to be acknowledged, understanding how past wounds are seeping into our present so that we can move forward with more acceptance.

I approach this book the same way that I approach my clinical work: by blending mindfulness, spirituality, attachment theory, and Internal Family Systems therapy—all through a traumainformed lens. I pull from both Western and Eastern psychology and philosophy, specifically Buddhism, integrating the mind, body, and spirit.

Are You Mad at Me? is about holding ourselves with the degree of compassion that we’ve always wanted but thought we didn’t deserve. It’s about shedding the protective mechanisms that are keeping us stuck in the past and away from the present. It’s about releasing the belief that we need to neglect ourselves for the comfort of other people. It’s about removing the conditioning and the blockages that have disconnected us from the true essence of who

we are and what we want in life. It’s about cultivating a sense of internal safety so that when everything else seems to be chaotic and out of our control, we have a quiet place to come back to.

This isn’t a quick fi x, because we’re not some piece of machinery that needs to be repaired, and I am not an all-knowing being who holds the secret to your healing. I hope these pages reveal what you’ve known all along but has been blocked by your pain and conditioning. Healing is an imperfect, lifelong practice of realizing that we were never “broken” to begin with. It’s a dance of forgetting wisdom and remembering it, again and again. My greatest hope is that this book supports you in your remembering. If, by the last page, you understand your patterns more clearly and hold yourself with more compassion, I’ve done my job.

Because once we stop focusing so much on what others think, we can remember who we are.

What the fawn response is and how it has protected you

Throughout my childhood, I was often told that I was too sensitive. I was hyper-attuned to what was happening around me. I felt deeply and cried easily, about both pain and beauty, and I didn’t get why that was so wrong.

When I was nine years old, my mom, bless her heart, sat me down and said to me softly, “Honey, I think you’re starting to experience bodily changes that are creating more . . . hormones. And maybe that’s why you’re so sensitive.”

Oh, cool. I nally have an answer.

I went up to everyone I saw that day, hands on my hips, and proudly declared, “I have hormones!”

As I got older, I started to feel shame about my sensitivity, like it was an ugly, inconvenient disease. “You’re so sensitive” is rarely said as a compliment. My views on sensitivity are different now: I see it as a subtle superpower that allows me to feel things deeply and to get a clear sense of what others may be feeling. What I now celebrate about sensitivity is also why it sucked when I was growing up: I could feel what others were feeling—or, rather, I could sense what others weren’t allowing themselves to feel.

As I later went through my graduate program and learned the ins and outs of trauma and its impact on the body, I started to question: Was I “too sensitive,” or did I learn to be superalert to people’s emotions and mood shifts because my dad’s rage could ip on like a switch at any moment? Was I “too sensitive,” or was I just

feeling all the unaddressed pain and tension that existed within the walls of my home? Was I “too sensitive,” or did I just know more than my parents thought I did? Was I “too sensitive,” or was it a fawn response?

Our brains’ primary job is to keep us safe, plain and simple. This animalistic, survivalist part of our brains has been there since the beginning, for two hundred million years and then some, and is solely focused on basic motives such as avoiding harm, staying fed, and having sex. It’s also in charge of the responses we slip into when we don’t feel safe. When our brains think there’s a threat of some sort, whether that threat is real or perceived, our nervous systems have four responses to turn to: fight, flight, freeze, and fawn. This book focuses on fawning, which is the least talked-about trauma response yet arguably the most common one. “Fawn response” became a term only in the past decade or so, coined by the psychotherapist Pete Walker in his 2013 book Complex PTSD: From Surviving to riving. The other three threat responses are a bit more recognized: the ght response is about being aggressive toward the threat to make it go away (e.g., yelling or beating it up). The ight response is about physically leaving the environment or relationship (e.g., running away or ghosting). The freeze response happens when we can’t physically leave, so we do the second-best

thing by mentally departing and blocking out what’s going on (e.g., dissociating, numbing ourselves, constant daydreaming).

But the fawn response? Oooooooh, the fawn response is about becoming more appealing to the threat, being liked by the threat, satisfying the threat, being helpful and agreeable to the threat—so that you can feel safe. Fawning is unconsciously moving toward, instead of away from, threatening relationships and situations. It’s overlooked in our society because it’s so largely rewarded. We get promotions for being people pleasers. We’re called selfless when we neglect ourselves. We receive affirmation when we anticipate the needs of others and abandon our own. For many people, particularly for many women, the fawn response is learned in childhood and then reinforced by society; we’re taught that our main role in life is to please, appease, and sacrifice our needs for the comfort of other people. Fawning has been a tool for survival, an unconscious way to feel in control in a society that strips power from us.

These four responses are not fi xed traits, nor are they our destiny. We can slip into any and all of them at different points in time based on what our survival brains and bodies think will be the most effective.

Fawning isn’t a conscious choice; it’s a genius survival mechanism.

Walker explains that a fawn response develops in chaotic home environments when a child learns that the fight response escalates

the situation or abuse, the freeze response doesn’t offer much safety, and flight isn’t always a feasible option. So, as an alternative survival strategy, the child “learns to fawn [their] way into the relative safety of becoming helpful.” 1 All these stress responses are useful, adaptive, and necessary—but we’re supposed to be in them for only a few minutes or hours at a time, not for years on end. Yet for so many, a chronic fawn response is as natural as breathing.

For most of my life, I thought fawning was just my personality. I almost took pride in it, thinking I was simply a cool girl who didn’t have many preferences or opinions. I could be a chameleon in social circles that I didn’t even want to be a part of and adjust my personality to be palatable to whomever I was trying to please. That chameleon–cool-girl vibe was genuinely protective for a long time. I’d closely monitor my dad’s moods and say the right thing at the right time, or not say anything at the wrong time. When I noticed my dad’s behavior start to escalate, I did anything I could to prevent an explosive outburst. Honestly, it was just easier to make sure he was happy than deal with what would happen if he wasn’t.

Maybe if I’m happy and perfect and good, he’ll be happy, too. Maybe if I’m likable, he won’t get upset at me. None of this was conscious, deliberate thought fawning is an unconscious response.

Yes, fawning was protective for me then, but when I was past that time in my life, I was left feeling far from myself, like I hadn’t yet met this person who was supposed to be “me.” I’d look into people’s eyes and think, What do they want me to say? And I’d say that.

I remember a seemingly small moment when I started to question whether this laissez-faire attitude was something less than positive, a sign that I had perhaps been neglecting myself. I was picking out bath towels for my first New York City apartment (read: shoebox), standing idly in aisle eight of Bed Bath & Beyond with no idea what to choose. I realized that I had zero clue what my favorite color was. My favorite color! I remember thinking, Let me go on Instagram and see what other people like. My next thought hit me like a punch to the gut: Am I even real? Or am I just a medley of other people’s personalities and preferences? Who am I when I’m not trying to please everyone else?

As you start to become aware of the fawn response in your own life, you may be thinking, When am I fawning, and when am I just being a nice person? As humans, we’re hardwired to connect. We’re prosocial beings who naturally want harmony and belonging. Healing the fawn response does not push against that innate desire—it moves toward it. We can’t be connected to others if we’re not connected to ourselves.

With fawning, we have to abandon ourselves in order to make the appeasing possible. We learn that the other person’s comfort is more important than our own, that we can’t feel okay until the other person is okay. We learn that, in order for us to feel safe, we

need to keep the peace, whatever it takes. And as a result, we’re disconnected from questions such as What do I need? What do I think? What do I want?

What we’ll come to understand together is the true difference between being nice and being compassionate. Nice is about how we’re being perceived—it’s doing something for the sake of being seen as good. Compassion is about authenticity, doing something because it feels good to be kind. It’s not compassionate if we’re constantly abandoning ourselves in our relationships. Being nice is often easier and a way to avoid conflict, but it can create long-term resentment if we’re constantly sacrificing our needs to make someone else happy. Motivation matters. Why am I doing this? Am I saying yes because I want to or because I’m scared this person will be upset if I say no? Am I complimenting this person because I mean it or because I’m trying to make them like me? When we can pause before engaging in habitual behavior, we can get clear on the motivation behind it.

A key component of fawning is something called hypervigilance, which is a state of heightened awareness in which the nervous system is extremely alert to potential danger or threat—whether there’s an actual threat or not. In this state of alertness, the brain is continuously scanning the environment to find the threat. It’s normal to experience brief moments of hypervigilance: like when

you’re trying to fall asleep and then you hear a weird noise downstairs, your heart starts pounding, and you begin mentally mapping out an escape route to save your dear life—and then you realize the weird noise is just your dryer. Hypervigilance complete. But for chronic fawners, that feeling of alertness is a daily occurrence, and it’s exhausting. Anything and everything feels like a threat to the body. This hypervigilance carries over into emotional monitoring, which means we’re constantly scanning other people’s emotional states to gauge what they may be feeling so that we can adapt. Again, this occurs naturally through a part of our brains and is highly useful. But for those stuck in the fawn response, hypervigilance is on overdrive and happening when we’re actually safe, leading us to analyze, ruminate, and worry: Are you mad at me?

Enter the “new” brain. It’s the part of our brains that makes us uniquely human and it has evolved over time to develop new abilities, like planning, analyzing, reflecting, imagining—and, in the case of fawning, ruminating for days on why your friends, who clearly saw your Instagram story, haven’t responded to your text. To showcase how the human brain is so tricky, let’s use one of my favorite visuals from the psychologist Paul Gilbert, founder of Compassion-Focused Therapy (CFT). First up, the animal brain:

A zebra is chomping on grass, basking in the sun and enjoying his delicious lunch. He then sees a lion out of the corner of his eye. His blood starts pumping and his heart starts thumping, ready to make the next move for his survival. Okay, here we go. In a split second, the zebra will make a decision. He’s going to charge in the other direction, in one, two . . .

And then the lion saunters away, distracted by his next victim. Phew. The zebra immediately begins to calm down. The threat is gone. His nervous system is back to a normal, regulated state. Life is good. Back to eating grass.

Oh, to be a zebra.

For humans, life isn’t as simple. We have the same survival instincts as zebras, but thanks to the new brain, we also have the ability to replay things in our heads, overanalyze, and fi xate. So while a zebra will immediately go back to an internal feeling of safety once the threat is no longer present, a human has the ability to replay what just happened a million times in their head and think, What if the lion comes back? What if the lion has a master plan to attack me in my sleep? Is the lion mad at me? Was it something I said?

This means that our bodies can stay in that state of hypervigilance they entered when the lion was right in front of us. As humans, we can slip into survival mode whether the threat is real, remembered, or perceived.2 We can have a threat response when we’re actually safe—and we can stay in it for years, decades, a lifetime.

Anxiety is like an alarm system in that sense. Your body has wisely learned to look out for certain cues that set off the alarm

(e.g., mood changes, body language), and when it notices them, the alarm starts blaring whether or not the threat is there. Even when you’re perfectly safe, your body is physiologically responding as if you’re in danger, waiting for the lion to pounce.

Isabelle, forty-three years old, sits across from me and reaches her arm out for another tissue to add to the growing pile on her left. It’s our fifth session together, and she’s telling me how, from the outside, it appeared that she grew up in a supportive home with the whole shebang: two parents married to each other, an older brother, a younger sister, and a fluff y dog that barked way too loudly for his size. But behind closed doors, her parents argued constantly; the air was always tense. Most of Isabelle’s childhood memories are of being alone, hiding in the pages of a fantasy book borrowed from the library, left to soothe herself in the hope that her parents would make up by the time she got to the acknowledgments section.

She’s been a self-described people pleaser her whole life, with a deep, dreadful feeling that something is wrong with her.

“I know this sounds horrible, but sometimes I wish something ‘big’ had happened to me, so at least then I could feel like I had a ‘real’ reason to feel this way. Then maybe people would believe me, and I’d believe myself.”