Translated from Swedish by Elizabeth

DeNoma

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published in Great Britain in 2025 by Doubleday an imprint of Transworld Publishers

Copyright © Sverker Sörlin 2025

English translation copyright © Elizabeth DeNoma 2025 The cost of this translation was supported by a subsidy from the Swedish Arts Council, gratefully acknowledged

The moral right of the author has been asserted

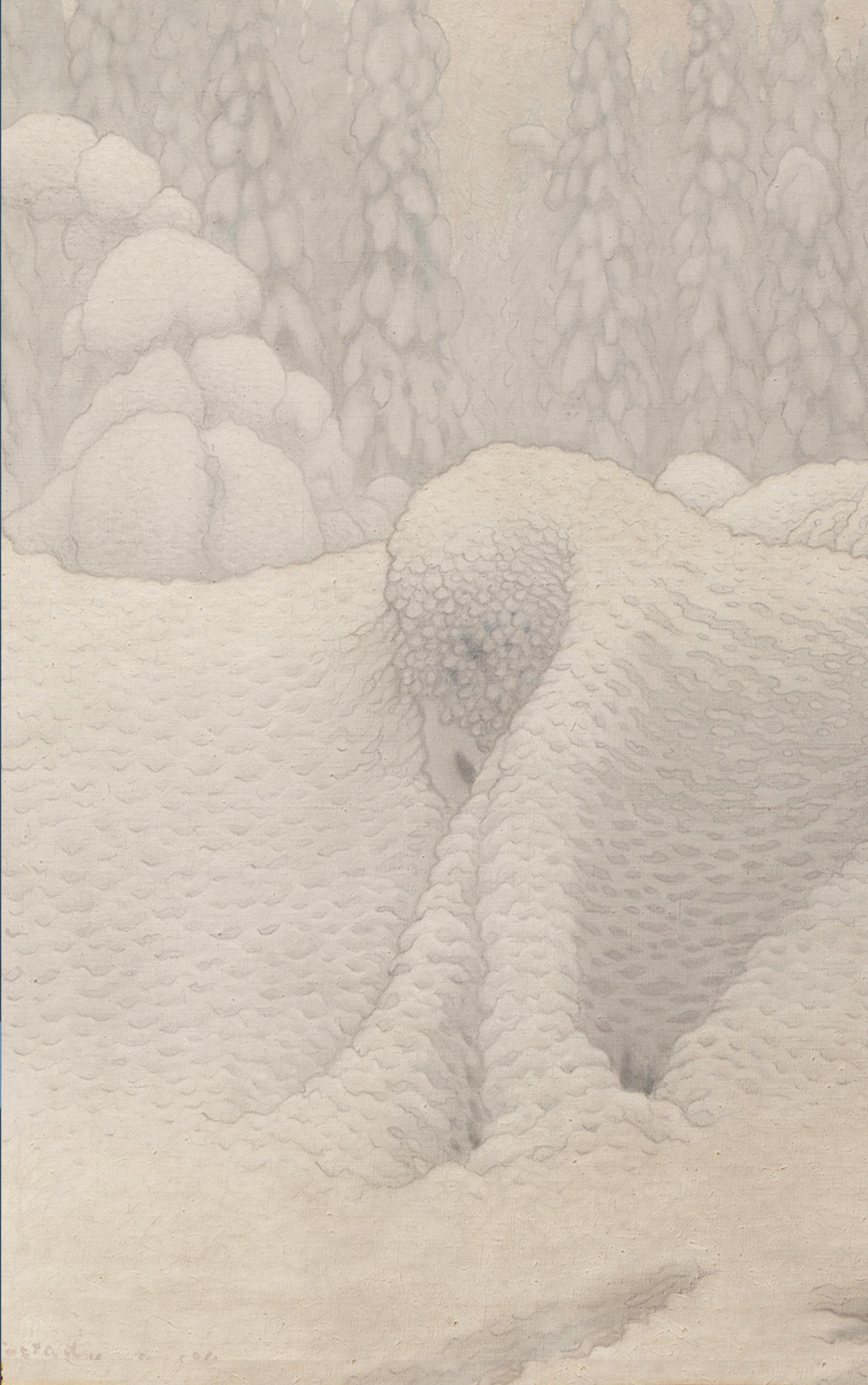

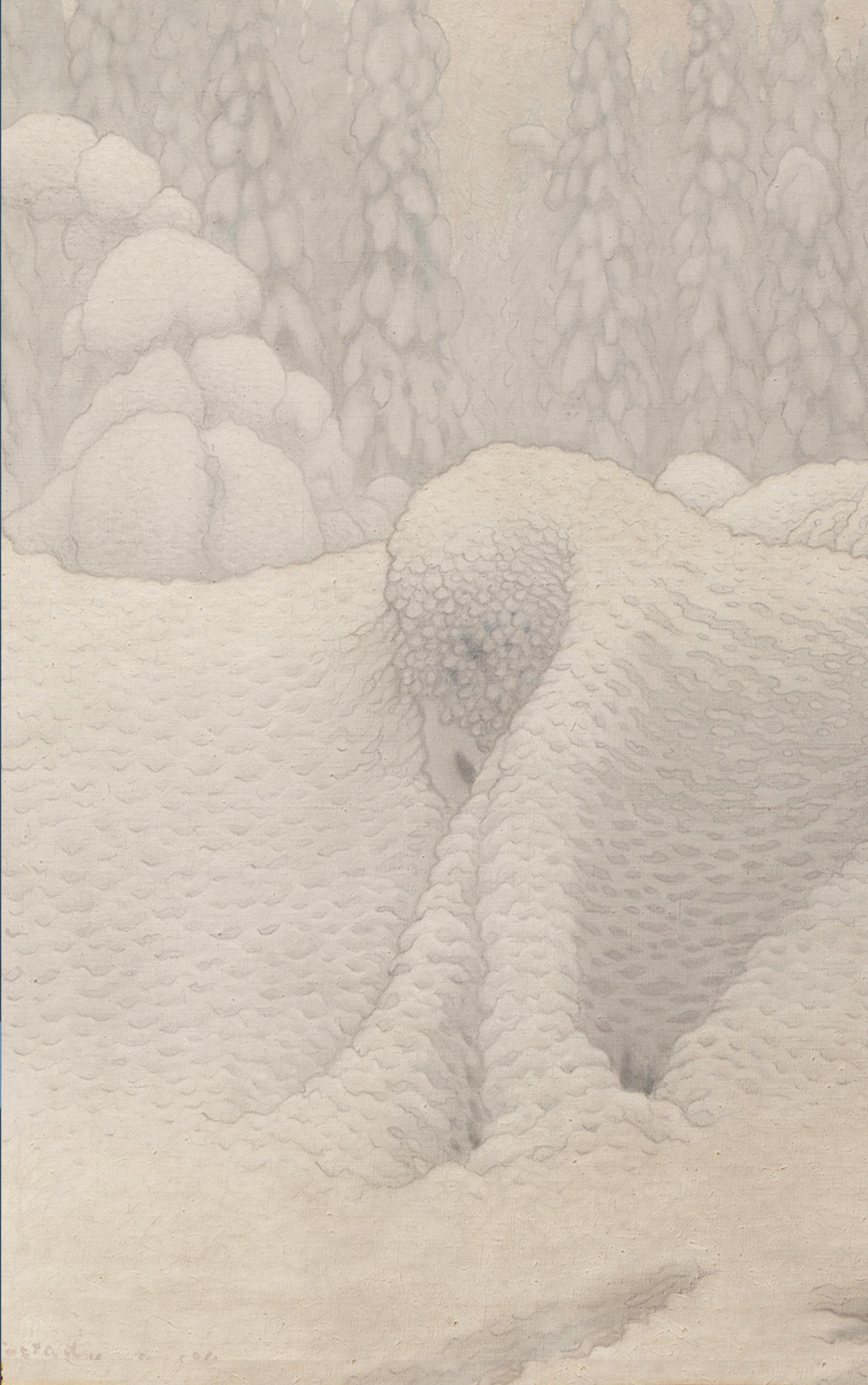

Text illustrations copyright © Lukas Möllersten 2025.

‘Snow Is Falling’ on p. 43 by Tomas Tranströmer from New Collected Poems, trans. Robin Fulton (Bloodaxe Books, 2011).

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset in 11.1/15.2pt Calluna by Six Red Marbles UK , Thetford, Norfolk Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d02 yh68.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBNs

9781529947878 (hb)

9781529947885 (tpb)

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

Hast thou entered into the treasures of the snow?

Or hast thou seen the treasures of the hail, Which I have reserved against the time of trouble, against the day of battle and war?

Hath the rain a father?

Or who hath begotten the drops of dew?

Out of whose womb came the ice?

And the hoary frost of heaven, who hath gendered it?

Job 38: 22–23, 28–29

Pay attention to these words. See the image in front of you. An angel in the snow. A white figure with wings spread wide.

I’m lying on my back with my eyes momentarily closed. I move my arms upward and downward. Soon I’ve created an improved version of myself.

I have always thought that a book about snow should start with those words. Everyone living at the northern latitudes knows what a snow angel is. Many people have themselves made them. Do angels exist? Snow angels exist. That is something certain.

Snow angels exist for a moment in time. Until the new snow falls, covering them up; until some angel-hater destroys them; until they melt away. An angel made of snow is a beautiful image of hope and impermanence, created out of a human desire for a different, better, state of things. The kind of desire which nowadays might sometimes be called childish.

A snow angel is the opposite of Jewish- German philosopher Walter Benjamin’s ‘Angel of History’ – the angel with its eyes wide open in terror, its wings stretching towards the sky

but paralysed by fear, its rigid, anguished body moving backwards into the future, hurled in that direction by a storm emanating out of Paradise. The horror never loosens its grip on the Angel of History, because the angel sees before it all the suffering and evil that history has produced. All the terrible things people have done to each other and to Creation. Everything that the rest of us don’t see when we have to turn our backs on the past, looking ahead, to see where to place our feet, perhaps filled with hope, confidence and the positive thought that what lies ahead of us may be more beautiful.

The angel sees what we leave behind and dare not look back upon – for fear of perishing.

Benjamin, who later saw his own books destroyed by the Nazis in their book-burnings, came up with his idea in 1921, when he’d bought a painting of just such an angel by the Swiss artist Paul Klee. The most awful thing about the Angel of History is that Benjamin’s interpretation is correct. That’s what history is. And that’s what the future will also be, at least to some extent. To reduce some part of that evil and suffering, we humans must take some responsibility.

This is how I see the role of the snow angel in our lives: as mankind’s way of exorcizing the future and strengthening us in our mission to improve ourselves. With my eyes on the constellation of stars above me, with moral responsibility within me and the whole of the earth beneath me, covered with this fragile, soft white blanket of impermanence, I ward off the forces of evil with my simple angelic gesture, demonstrating with my fumbling wings that the earth can transform into Paradise. The way that we have to believe that Sisyphus, eternally rolling his boulder uphill, is happy. That it’s meant to be, even if we know that’s not exactly what

it’s going to be like. I want these two very different angels – of history and of snow – to at least be able to talk to each other, and I think that’s why I’ve always wanted to write this book.

Snow is hope – renewed annually, with new snow replacing that which fell last year and which has already disappeared. In literature, they say that snow is a symbol of transformation. When there’s snowfall in poetry and novels, it’s often to demonstrate that the characters in the text are turning inwards in reflection. They become receptive to forces or messages that can help them reach another, better, state of being.

Snow is also history, having been a companion to people’s lives in many parts of the world, especially in the northern hemisphere, and even more so for those of us living in the far north. It’s about time that the snow angel and the Angel of History started conversing.

What’s happening to snow is something that the Angel of History is seeing more and more of as we humans make our way through the world. Where once there was a real winter with snow, now bare ground makes an appearance during seasons that have lost their rhythm. Snow is in retreat, as part of the great historical drama now known as climate change. It’s not the first climate change that history’s allseeing angel has witnessed. But it’s the first that human beings have themselves brought about on a planetary scale. The first climate change that is, in the deepest sense of the word, historical, that is to say, part of the history of human actions.

When was it that the first snow fell on our planet? The very question itself previously seemed comically fantastic. Now

there’s an answer: 2.5 billion years ago. In 2018, a group of geologists published an article in the journal Nature, presenting a theory for how large continental land masses first emerged out of the seas, and how Earth subsequently started reflecting light from the sun back into space. The planet’s temperature dropped, causing runaway glaciation that eventually left it in a state known as ‘Snowball Earth’. Ilya Bindeman, a professor of geology at the University of Oregon, who led the research team, said in an interview, ‘That’s when the earth got its first snowfall.’

The world’s oldest ski is 5,400 years old. More recent than the first snowfall, but still long before anyone uttered the word ‘Sweden’. It was found in 1923 near the village of Kalvträsk, between Skellefteå and Lycksele in what is present- day Västerbotten, the second-northernmost county of Sweden. Another ski, almost as old, was later found in Hoting, not far from the Ångermanland border, and less than forty kilometres from where I grew up. In sparse, rugged Sweden, people in the countryside were reluctant to carry their loads across the bare ground, in terrain without roads. Winter was better; anything heavy and unwieldy could be towed home over the snow – things like timber or firewood from the forest, or hay that had been cut and hung on hayracks or put into barns along the river banks. Skis are faster than snowshoes, especially in areas where temperatures sometimes hover around zero, causing the snow to melt and freeze. On skis you could pursue moose and bears, which had a hard time in deep snow. Snow meant freedom and protein.

Before steamboats or railways existed, merchants in the north transported goods by horse and sled along the Gulf of

Bothnia coast. Our vast country was held together by snow and ice. Snow was the basic prerequisite.

Growing up as a little boy in the snowy interior of Västerbotten, and in southernmost Lapland, in northern Sweden, snow was never something I associated with ‘history’. History, we were taught at school, was what had happened in other places. Almost always further south, where Sweden’s kings had fought wars in continental Europe, and where popes and parliaments made important decisions. These decisions were certainly relevant to us and affected our lives. But they didn’t affect the basic conditions of our existence, which when it came right down to it, were more influenced by the seasons, and by the climate.

Snow was a part of that. It was indeed the underlying foundation of our lives, if one that wasn’t always appreciated. Loggers cut down large timber for export, making Sweden rich. They did their work under mighty tree branches that were usually weighed down by thick layers of snow – opplegan, as it was called in our dialect. Snow that fell on those loggers had a strange way of making it through the collars of their shirts, chilling their necks, melting and running down their backs and dampening their thick underwear with snow-melt. That was before the term ‘work environment’ came into use. But the snow was, at its heart, something practical, and without it the development of the forestry industry would have been limited. It was on the snow that timber was transported to lakes, streams and rivers. And it was on the snow that the loggers made their way out to the clearings, mostly on skis. Some of them became skilful racers, in the generations that dominated cross-country skiing from the Second World War until the 1970s.

I grew up on snow, too. There was snow for more than half the year. That’s not a fact I’ve pulled out of thin air or even from memory; I’ve consulted records from the Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute (SMHI). The number of snow days per year in northern Norrland, which includes Västerbotten and Lapland, averaged between 180 and just over 220 throughout my childhood and youth. The peak was the winter of 1968– 69, with snow cover lasting nearly eight months even in places outside the mountain range. Snow was the normal condition, as was the cold. The snow was such an obvious thing that there was no reason to waste time on it. No one thought it had anything to do with history. Or that it could be connected to politics. My grandfather was a politician, sitting in parliament, the county council and the municipal governing body. But when he talked about politics, as he sometimes did at home with us, it was never about snow. Snow just existed, like something eternal that had to be shovelled from All Saints’ Day until Walpurgis Night.

It’s just that I loved it. Others sighed; I was happy. My joy came spontaneously, irresistibly. I didn’t know why. That’s just the way it was. I wasn’t at all alone in this feeling. Most of us liked the snow when we were little. People only started complaining about it as adults. I realize now that what I sensed in myself even then, without having words for it, was that snow can be understood, at its deepest sense, as history. It’s also physics, chemistry, meteorology, anthropology, economics, technology and geography. Yes, poetry, art, music, dance and sculpture, too. And very much politics.

It’s important right now to see that snow is historical. It appears within time. And as the kind of element that compels

our attention, snow is growing – in our consciousness, it’s getting bigger. But out there, in the environment, it’s getting smaller. It’s disappearing. This is our own doing. Snow isn’t simply a mysterious gift from the heavens. It’s increasingly becoming recognized as a part of history. At the same time, in many places it’s already history, in the sense that it no longer exists.

I feel this within me. Snow is inside me and it’s painful when it disappears. I have images from my childhood in the snow that I carry with me in my life. Only recently have I been able to make sense of them.

Snow – just a lone, single word for an infinite variety of individual expressions of water, frozen in air. We sometimes hear the word from the teacher standing behind the lectern, but the teacher’s way of describing snow doesn’t impress us very much. As a boy, I am told that in Greenland there are a hundred words for snow. I wonder to myself if that is true. Maybe it is – after all, snow is marvellous. But still . . . is that possible? Isn’t it just another one of those exaggerations that the world seems to be full of? I have realized early on that much of what we hear is simplification; received wisdom that isn’t always true.

Many years later, I was to read the author and ethnologist Yngve Ryd’s book on words for snow in the Lule Sámi language. It contains more than three hundred words, passed on to Ryd by the reindeer herder Johan Rassa and his wife Ibb-Anna from Jokkmokk. The book is unique – it has no real equivalent anywhere else in the world. In the 1940s, the national dialect archive located in Uppsala sent out a list of questions about snow, but the answers are ‘succinct

and sparse’, says Ryd. From out of his and the Rassas’ book, however, a whole world emerges, like a powerful symphony of knowledge, experience and poetry about a culture and a landscape occupied by animals and people and myths. And this is still only the beginning of the world of snow. Snow is a state of being – an internal one as well as an external one. One for the place and one for the planet.

I like the snow. In almost any form it takes. Adults tend to be dubious about it. A child, on the other hand, rushes out, eagerly grasps the white substance and immediately begins to shape it. As if they had caught hold of something that could become . . . a new world. That’s the way I am. Quite naturally and without knowing why. And when I think back to my childhood self now, I realize that even then, without knowing it, I perceived the snow as historical. Something that was part of being human in the world, and something responsible for shaping that experience.

But I didn’t know what we now know. That snow is no longer a given, the way that I thought it was. It’s at risk. It challenges us. It’s our conscience.

Snow is on its way out. At an uneven pace, but inexorably. Now, more than ever, I really want to understand its qualities. This feels absolutely essential. There’s no other substance as important to us about which we know so little. Snow is a transitional substance. Neither stable nor certain. A liminal form. At the same time, it’s ordinary water, but in an ambiguous position somewhere between free molecules in the air and the hard, stable ice that can last for millions of years.

It’s snowing – this airy substance that appears only from time to time, under very specific, and actually quite

xviii

infrequent, conditions, which happen to be prevalent to an unusual extent in the Nordic countries. What I’ve always considered a given is, on the contrary, something rare. And it’s becoming more and more rare. That’s because we humans are warming the planet. And this is exactly what compels us to turn our attention to snow right now. To ask questions of it, to want to know more about it. Like how it’s come into being, what it is, what it’s no longer able to be. We can use it to learn more about the dangers of our current moment. Snow can help us to see our self-inflicted misfortune.

Those of us living among the forests and mountains in the Nordic countries have a special responsibility for this task. We know the peculiarities of snow; its strangeness. And we’re learning new things about it all the time. Like the fact that monkeys also make snowballs, but they don’t have snowball fights. And that snow has politics. Contrary to what we thought – that it just fell and fell and would always fall without caring what humans did. But it turns out that it does care.

Perhaps the strangest thing is that the qualities of snow also reside within us. Those of us who live and have lived with snow have, I think, internalized some of its qualities as part of ourselves. Whether we love the snow or not. Perhaps with horror at the cold of it and the disruption snow sometimes causes; or, as in my case, with deep affection and a warm trust in the snow as our wise ally.

I’ve always had this trust. Alongside a strange happiness that I’ve been able to retain through the intervention of some unknown angel. A fixed point in my mind that I can return to when I find it hard to breathe. Snow is the most important element in the reliable wheel of the seasons.

We need all of the seasons, because they’re not the same; they have different missions. Autumn is the second-best; it is the anticipation of winter, which is the best season of all. The leaves fall early in inner Västerbotten – a couple of hours from Ådalen’s timber industry, on the Gulf of Bothnia in the east, and a few hours from Trøndelag in Norway, by the Atlantic in the west.

And then, one morning, from my boyhood bedroom: I see the light outside, before I even open the slatted blinds. Snow! The miracle of whiteness is shining through the slats. The ground that was dark yesterday is bright and radiant this autumn morning. No human being has been involved. Not even my grandfather, who usually controls so much.

Snowfall is an event. Something that comes to me. I’m a part of something, through forces that I have no control over. How fortunate that I, of all people, should happen to be in a place in the world where it snows! I love it because it’s a gift. It is the very order of the world; we’re all so small that we cannot compete with either the snow or the sky. They’re bigger than we are. And maybe that’s why I am so happy, and take such childish delight in being alive.

A silent collecting of snow. Eventually this becomes my project. Voices, images, stories. The more I collect, the more convinced I am that a deeper sense of snow is needed. It was ice and snow that made Sweden – we live in a winter wonderland. Why don’t we all care more? Why don’t we mourn the fact that the snow is melting?

I want to awaken the snow angel within us.

I’ve learned to Walk. My knitted ski helmet is on my head. Mum is in front of me, smiling, sparkling. I’m standing on my first skis. They’re blue. No span, no glide. When I’m going to sleep, my mother reads aloud from Elsa Beskow’s Ollie’s Ski Trip, or the books about Moominvalley. Snow belongs to the world of fairy tales. The books contain a truth that I make my own. Mum’s voice brings it to me. She doesn’t just read the words. She also lets me understand that this is something she believes in, and something that she wants me to believe.

Mum turns her face towards me. Rubs snow against my cheeks. I suppose I laugh. Her brown eyes and white teeth gleam. She was twenty-two when I was born; I will later realize that she’s beautiful. My mother’s voice becomes my Weltanschauung.

First of all there’s the snow itself. Snow is the finest droplets of water, frozen in air, helped by dust.

Next come the words. The Swedish word for ‘snow’, snö, comes from the Old Swedish sniö or snior, which in turn comes from the Old Norse snær (which is also a first name

in Icelandic). That in turn comes from the proto- Germanic snaiwa (from which also come the English snow, the German Schnee and the Dutch sneeuw ). The Indo-European root of all these words is (s)neyg (or snoyg, snoigu-ho ), from which the French neige and the Italian neve have also come about. Along the way, the Latin word nix, meaning snow, came via the Proto-Italic (Etruscan) sniks, with the root ɣ, which gave the prefix niv-, which is found in the word nival, as found in the expression ‘the subnival space’ – the space between the ground and the snow – or in the Sierra Nevada (‘snow mountains’).

Snow is a rich wordsmith. But perhaps it could just as easily be said that the reverse is true: snow emerges from these words. As the Gospel of John says, ‘In the beginning was the Word’. Without words, snow wouldn’t be so rich in meaning. Without words, we literally would not see the snow for all its whiteness. When physicist Henri Bader and his team of researchers in Davos, Switzerland, published a book on what they called the ‘metamorphism’ of snow in the fateful year of 1939, he began the book with a short threepage chapter about the word itself, Der Begriff ‘Schnee’ (‘The Concept of “Snow” ’). The gist of this was that when it comes to snow, nothing is stable. Snow is metamorphosis; its transformation never ceases. Bader’s approach is reminiscent of how Luis Buñuel began his 1929 film An Andalusian Dog – a razor blade through a woman’s eye (in reality a reindeer’s eye). It was something shocking! To make the reader receptive. To be more precise, snow forms from water vapour in the upper layers of air that cools as the air moves upwards. That water vapour then condenses into fine, flat ice crystals with a six-armed structure. In these conditions this crystallization

process needs something material for it to get started: particles, dust, a few molecules.

It’s the water molecule, with one oxygen atom and two hydrogen atoms, that readily forms hexagonal crystals. Snow crystals and snowflakes aren’t droplets of water that have frozen, but are made up of water molecules that change directly from vapour to solid form. Their structure can vary greatly depending on the temperature, humidity and other atmospheric conditions. If it’s really cold, between -12° and -16° Celsius, the ice crystal grows easily and forms the classic, symmetrical snow star with six arms or more, in some exceptional instances twice as many. When it’s colder, the snowflake becomes rounder. If it’s not particularly cold, the snowflake takes on a simpler shape.

Snowflakes fall at different rates depending on their size, density, temperature and the wind. But usually they fall quite slowly, around five kilometres per hour, about normal walking speed. That humanizes snow. It also moves the same way we do, crookedly and winding, floating and searching, turning sharply.

A snowflake is a collection of many snow stars – dozens, sometimes more than a hundred. Really big snowflakes form when the temperature is higher and the snowflakes are moist on the surface and stick together, which happens as the snowflakes are falling. When there’s no wind and it’s not too cold, snowflakes can become the size of butterflies. In Lule Sámi they are called sparrow halves, tsihtsebelaga. The word ‘half’ seems to imply two halves that want something from each other. In Swedish, we used to call large snowflakes lapphandskar – that is, Lapp gloves (or Sámi gloves) . My mother Gudrun would say, reverently, ‘It’s snowing Lapp

gloves!’ Then we children would come up to the window and look out and be filled with that reverence ourselves. Lapphandskar were something lovely, and I would watch with my own eyes as the large white flakes quietly and mysteriously floated to the ground, like in a film.

The expression has been around for a long time, at least a couple of hundred years. Fredrik Svenonius, the state geologist and fierce advocate for the Swedish region of Norrbotten, who was also a keen photographer, took a picture of a snowy landscape with his camera on 20 February 1899 and called it ‘It’s snowing Lapp gloves’. Petrus Læstadius, a missionary to Lapland, noted in his diary in the early 1830s: ‘In Norrland they still say that it’s snowing “Lapp gloves”, when the snow falls in large flakes.’ From this, we can conclude that the expression has been in use since long before that.

Such ‘Lapp glove’ snowflakes can be huge. The largest known snowflake is said to have been found at Fort Keogh in Montana, USA , on 28 January 1887. During a snowfall, a man named Matt Coleman is said to have come across a snowflake 38 centimetres wide and 20 centimetres thick. In Siberia in 1971, snowflakes ‘the size of A4 sheets’ were observed by several witnesses. In March 2024, snowflakes ‘the size of snuff-boxes’ were reported in the northern Swedish city of Umeå.

Snow can fall even when the temperature is above freezing, especially when the humidity is low, as is often the case in late winter and early spring. It can be 7°C outside and you might have caught a glimpse of the first blooms of spring – then suddenly your view is obscured by a swirling flurry of snow. But it usually passes quickly. When snow forms in stable, low-level clouds – typically stratus

or stratocumulus – it usually falls as flat, oblong, brittle ice particles rarely more than a few millimetres long, known as granular snow, which can be irritating to the eyes when it’s windy. So-called ice needles are even smaller. They fall from clear skies and consist of tiny, thin ice crystals that appear to float in the air. These are also called ‘diamond dust’. When lit by the sun, they create a shimmering effect reminiscent of gilded altarpieces. If there is a city somewhere above the clouds, the way there is probably through such dust clouds of light-transmitting ice.

Hail, too, counts as snow, and there are several different kinds. One type is called snow hail or graupel. The particles in graupel are similar to granular snow but larger, up to five millimetres in diameter. Snow hail bounces and often breaks on contact with the ground; sleet, meanwhile, comes in huge waves and doesn’t break apart. It can create rivers where it falls.

Hail falls from huge clouds and is sometimes accompanied by thunder, regardless of the season. It can fall at speeds of 150 to 200 kilometres per hour and can reach the size of grapes, plums – or even larger. Ice hail, the sky’s heaviest artillery, can dent cars and pierce shingled roofs; it can probably even fell an ox. The largest hailstone recorded under scientifically controlled conditions fell during a storm in Vivian, South Dakota, on 23 July 2010. It was 20.3 centimetres in diameter and weighed 0.88 kilograms. But there are written reports of even larger hailstones. One that landed in China in 1902 is said to have weighed four kilograms. One of the first Westerners to visit Tibet, in the 1840s, the French missionary Évariste Régis Huc witnessed hailstones there weighing five and a half kilograms, one of which was the size

of a millstone and took more than three days to melt in the blazing sun.

Compressed snow eventually becomes very hard, transforming over time into ice and, across widespread mountainous areas, into glaciers with properties similar to minerals. Snow itself can be classed as a mineral. It fulfils all the criteria: it’s homogeneous, non-organic, with a defined chemical composition (H2O) and a definite atomic structure. Like other minerals, snow occurs naturally, though mostly at temperatures below 0° Celsius.

Almost all snowfall – around 98 per cent of it – occurs in the northern hemisphere. In a typical winter, snow covers up to 40 per cent of the northern hemisphere’s land surface – more than 40 million square kilometres. Of course, the area covered varies from year to year, but the long-term trend is that it is shrinking. Snow is mainly found in North America, Greenland, Europe and Russia, but snow also falls in the Andes and Asia, as well as in New Zealand, south-eastern Australia, Patagonia and Antarctica. In Africa, snow falls in mountainous regions in the north, east and south of the continent. The Asian and Pacific archipelago, West and Central Africa, and central and western Australia, are areas where it virtually never snows. This is also the case in some desert regions of the Andes and in the driest areas of East Antarctica – the McMurdo Dry Valleys – which scientists believe have had their extreme climate for millions of years and consequently have no ice sheet, unlike most of the Antarctic continent.

In Sweden, most of the snow falls in the north, with less in the south. In Skåne, which is in the south, an average of almost 10 per cent of annual precipitation came in the form

of snow during 1960–1990. In Lapland, the corresponding figure was 40 per cent. That difference has probably decreased slightly since 1990, with the increasingly warm winters. The greatest proportion of annual precipitation is in the mountainous regions. At high altitudes, in Sarek National Park, the Kebnekaise massif and other high mountain areas, the proportion can be 70 per cent or more. It’s also in the mountains that the greatest depths of snow in Sweden have been measured.

The deepest was at Kopparåsen, near the Norwegian border, where on 28 February 1926 it is said to have measured 327 centimetres. The snow at nearby weather monitoring sites was nothing like as deep at the time, so even the field staff admitted there was some uncertainty surrounding this measurement. The Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute (SMHI) states, ‘Unfortunately, the last day of February was the last day when observations were made from the station and we don’t know what happened later to the snow depth or the person who observed it.’

In the village of Ulvoberg, in the Västerbotten region, one metre of fresh snow fell in June of 1932. A contemporary source says, ‘The snowfall and subsequent large amounts of meltwater caused a shortage of fodder in several places, and emergency aid had to be sent to the worst affected areas.’

In December 1998, winds from the Bothnian Sea drove in an intense snowfall that increased the snow depth in the town of Gävle by 130 centimetres within a period of three days. The snow was heavy, snow clearance couldn’t keep up with it, and for a time Gävle residents had to make their way through streets where the hard-packed snow was level with the tops of cars. Big snowfalls often happen in this way – cold,

dry air travels over large lakes or the open sea, absorbing moisture from the warmer water. The heated air rises and then cools, allowing the moisture to condense and form clouds. When these clouds come in over land and are pushed upwards, the moisture in them starts to be released in the form of snow. These snow-belt blizzards often form distinct lines along the direction of the wind, and can issue extremely large amounts of snow. Some of the biggest changes in snow depth in Sweden from one day to the next are the result of snow-belt blizzards like the one in Gävle.

The coastal city of Oskarshamn in Småland received 72 centimetres of snow on 3–4 January 1985 in a similar fashion. West of a low pressure system over the Barents Sea, very cold air flowed southwards with a north-easterly gale into a storm on the Baltic Sea. The surface water temperature was several degrees above zero, while the temperature at an altitude of 1,300 metres was -17° Celsius. The sharp temperature differences caused violent vertical air movements. Over the coast of Småland, clouds were forced further upwards. The effect was extremely localized: Oskarshamn had snow that was 110 centimetres deep; Misterhult, just 28 kilometres to the north of there, had 130 centimetres. A few kilometres south of Oskarshamn, the ground was practically bare.

The greatest snow depth at a research station outside the Swedish mountain region ever recorded by SMHI was 190 centimetres, measured at Degersjö, in the northern region of Ångermanland, on 2 January 1967. The station is only a few miles from the coast at Örnsköldsvik and Kvarken, the narrow region in the north-east between Bothnian Bay and the Bothnian Sea (literally ‘neck of the sea’), which meant that for a couple of weeks a series of snow-belt

blizzards thundered in over the land from the north-east. A weather observer by the name of Göta Vedin, in the nearby village of Ullånger, wrote in her diary on 1 January 1967: ‘There has never been such catastrophic weather since the introduction of electric power. Wires are down everywhere because of the sleet and the wet snow. The telephone lines have also suffered the same fate. This chaos has been going on since December 17th, and is still going on as of January 1st, and it seems to be getting worse.’

This type of heavy snowfall also occurs south and east of the Great Lakes in the United States, where snow depths of more than a metre can fall in a single day. Snow-belt blizzards form over large lakes in Europe such as Sweden’s Lake Vänern and Lake Ladoga in Russia, as well as in Japan, Korea and in the United Kingdom, as northerly winds descend over the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. The largest snowfalls of all categories occur in Japan and along the west coast of North America, but also in the Rocky Mountains, as in one instance at Silver Lake, Colorado, which received 193 centimetres of snow on 14–15 April 1951. A total of 480 centimetres fell on 13–19 February 1959 at Mount Shasta Ski Bowl in California. The largest total amount of new snow in a year (accumulated new snowfall) was recorded at Mount Baker Lodge in Washington State in the winter of 1998– 99, totalling 29 metres. The greatest snow depth in the world (accumulated snow on the ground) was recorded at Mount Ibuki in Japan as 11.82 metres, on 14 February 1927, after a fresh snowfall of 230 centimetres – the greatest-ever known amount of snowfall in a single day.

But despite its occasional abundance, snow, with its variety of manifestations, is something many people in the

world have never even been near. They’ve never walked with snow under their feet, never held snow in their hands, let alone stood on a pair of skis, built a snow bivouac, ridden a kick-sled – or made a snow angel.

The words used to describe snow have a certain permanence, even though the knowledge we currently have about snow is very different from what was known before. The Sámi words for snow, the words that ethnologist Yngve Ryd transcribed from Johan and Ibb-Anna Rassa in Jokkmokk, are now many generations old. Most have been around for hundreds of years. Some words probably arose with the emergence of wild reindeer husbandry, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Reindeer and their migration routes are important parts of this vocabulary. Tsievve is the word for hard snow that reindeer can’t get any purchase on with their hooves. Tjievttjemuohta is snow that goes up to the reindeer’s hock, while the snow that reaches up to the reindeer’s belly is called tjoajvevuolmuohta. There could have been other words from the long period during which the Sámi lived in the forests with the reindeer, during the first centuries of the previous millennium. Like other languages, the Sámi tongue is largely lost in the obscurity of time and a culture that wasn’t recorded.

Swedish words for snow also have a history. Skare, meaning ‘snow crust’, has been documented since the seventeenth century, while klabbföre, meaning ‘snow that sticks to the bottom of the skis’, came into use when skiing became common, around 1900. Words like ‘crystals’ and ‘diamonds’ appear in the very oldest texts on snow, from antiquity and the early modern period, by which point they are already

established metaphors for it. This is the case in other languages, too. It’s as though even early vocabulary around snow was associated with a higher sphere, in contact with a near-supernatural reality. I don’t think this is a coincidence. The snow comes out of the sky, as does the rain, and they are, of course, related – but still different. Snow isn’t rain. The quest of a dignified, drifting snowflake is light years away from the common, pattering raindrop, suspended vertically over its focal point on the ground. Snow is transformed somewhere on high, by a force that humans can’t control – the cold. People could melt the snow into water, but the reverse – making snow from water: that they could not do. Humans own the heat, not the cold, as the French natural historian Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, put it in his imaginative and encyclopaedic 1778 overview of the history of the earth and the human impacts on it, Les Époques de la nature (‘The Epochs of Nature’). It was Buffon who discovered that history is within everything. The only thing I’ve added is . . . snow.

Snow’s origin is magical. Even more magical than that of ice. Freezing was indeed impressive and that, too, couldn’t be achieved by humans, but how it was formed was visible to the naked eye; you could watch it happen, and even supplement it by providing additional water.

But the snowflakes – who made them? And according to what plan?

Soon I t’S the 1960 S . With those long, cold, snowy winters. I remember that as soon as I got out of bed in the mornings, I used to run to the thermometer by the kitchen window. Then I’d rush in to wake up my dad and tell him how cold it was. Around -37° Celsius was the norm. He always affirmed what I said, ‘Oh, still just as cold!’ The cold was our joint project. The statistics from SMHI show that I remember it pretty well. There were weekly temperatures of between -30°C and -40°C. Some days even lower.

One day it’s -45°C. We go to school as on any other day. The children from the villages far away get the day off, because using transport to get to school is too dangerous. But the kids from Söråsele, two kilometres away, come in on their kick-sleds as usual. With white hoarfrost on scarves wrapped around their mouths and noses, as if they were wounded soldiers from an unknown winter war.

Sliding in the hallways in our woollen socks is sport for us middle schoolers on these quiet, crystalline days. Or on the reindeer-skin shoes, for anyone who had them. Then you could give your friends an electric shock from the static. Especially the girls, who there was otherwise no acceptable reason to touch (except at the school dances in the darkness

of the gymnasium to the sound of The Hollies and The Shanes).

School sports take place in the snow. I tumble in big piles of snow that the snowploughs have heaped up. In the schoolyard, we make tunnels to crawl in, to take refuge in during our snowball fights. In there, inside the snow, where no one can stand up straight, something feels off to me. I don’t know what it is. Only that it freezes my very core.

In August of 2019, an unusual memorial ceremony was held in western Iceland. People gathered at Borgarfjörður to bid farewell to the Okjökull Glacier on the slopes of the extinct Ok volcano. The glacier site is now called Ok, too, ever since the jökull – which means ‘glacier’ – part of its name was removed because the glacier itself had become extinct. Pronounced dead by Iceland’s expert glaciologists. Mourners gathered to remember the glacier, which had been there for as long as humans had been in Iceland, since the early 800s ce , and for thousands of years before that. Layer upon layer of snow, year after year. Now it was . . . well, maybe not dead, because there was nothing that had been alive and no body. But it was gone. Its existence had ceased.

Ok won’t be an isolated case. Dozens of glaciers have already disappeared and, at current emissions levels, the majority of Iceland’s four hundred glaciers will have melted away by the end of the twenty-first century. Already threatened is the glacier at Snæfellsjökull, the volcano featured in Jules Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth from 1864 , in which the character of Hamburg professor Otto Lidenbrock descended with his guide Hans and nephew Axel in search of a lost underground world where tumultuous seas, petrified

trees and wondrous ancient animals awaited, miles beneath the earth’s surface.

Jules Verne’s story is reminiscent of Plato’s Atlantis, the mythical island that had sunk into the sea, but also of the new dynamic concept of the earth that became increasingly well-established by the middle of the nineteenth century. Darwin’s theory of natural selection had been published just five years earlier. Theories about an ice age that had paralysed the northern hemisphere, wiping out the mammoths and other ancient species, had been around for more than twenty years. Perhaps most importantly, at almost exactly the same time that Jules Verne was working on his novel, geologists – practitioners of a relatively new profession – were beginning to consider whether they needed to introduce another epoch into the earth’s timeline. That is, a new top layer in the stratigraphy (from stratos, meaning layer).

The proposal was made by the French geologist and palaeontologist Paul Gervais in 1850. Gervais was mapping mammalian fossils when he was struck by the idea that a case might be made for a specific term for the geological period that included the presence of human beings. He published an article on the subject in a journal issued by the Montpellier Academy of Sciences and Letters. His request wasn’t immediately granted; it took more than a century, as it turned out, but in the 1980s the new post-glacial period was finally recognized – under the name proposed by Gervais, the Holocene. By that time, geologists and palaeontologists knew that there had been at least a dozen ice ages, which had come and gone over millions of years. The greater depth of ice ages behind us doesn’t make it any less important to emphasize that the post-glacial period, the

one in which modern humans are living, is nevertheless a different time.

Nowadays, each newly discovered geological period has a stratigraphic marker, a round brass plaque inserted into the earth’s crust at a point where the characteristics of that period become clearly visible. For the Holocene, there’s no such ‘golden spike’ in the visible environment, however. That’s because stratigraphic experts concluded in 2008 that what is most representative of the end of the last ice age is the layer in the Greenland Ice Sheet that corresponds to snow that fell approximately 11,700 years before the year 2000, which is the year when the shift to a warmer climate presents itself most clearly. That layer, encapsulated in a sample ‘drill core’ extracted from the ice sheet in the year 2000, is found at a depth of 1,492.45 metres. That thousands-ofyears-old snow has been preserved there, below 1,500 metres of snow accumulated at a rate of around ten centimetres a year, since it first landed on the glacier almost 12,000 years ago. This critical ice sheet contains the boundary between the Holocene and ‘civilization’ itself, and is stored, somewhat unglamorously, in a cardboard box among other segments in a large freezer archive filled with sample cores at the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen.

It’s worth pausing a bit to consider history. After 2.5 billion years, snow is making its return as a means of dating Earth’s past. The first time was ‘Snowball Earth’, when snow first covered the planet. In our own time, for those of us living in the present day, after this long loop of billions of years and more than a hundred geological eons, epochs, periods and ages (geologists work with a lot of different concepts regarding the eras of the earth), snow is back in

the stratigraphy – at the very moment that it’s starting to disappear. The end of the last ice age is nothing but the beginning of a warmer period. The Holocene has been climatically fairly stable for almost twelve thousand years. But over the last century, the Holocene has shifted into the ‘Anthropocene’, the age of humans. And in the Anthropocene, we’re the ones who are warming the planet, and what we have seen so far is just the beginning of a rise that is certain to continue for a long time, probably pushing the temperature up by 2.5 or 3 degrees, maybe even more. That’s what’s causing the snow to leave us.

That’s also what necessitates the mourning ceremonies at glaciers. At the tombstone during the solemn ceremony for Ok, Icelandic prime minister Katrín Jakobsdóttir and former UN Human Rights Commissioner Mary Robinson were joined by about a hundred other people who wanted to show their commitment to preserving cold in the world and, accordingly, Iceland’s and the world’s glaciers and snow – and all those who depend on these elements, in some cases for their survival. There was a short text written on the tombstone: ‘A letter to the future’, by the author Andri Snær Magnason. The text ends with a message to future generations:

This memorial acknowledges that we know what is happening and what needs to be done. Only you know if we did it.

The plaque also bears the inscription ‘415ppm CO2’. This was the average level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere at the time of the ceremony. The figure is the result of a

A history

measurement carried out at a research station at the Mauna Loa volcano in Hawaii. At the same time – without saying so explicitly – it is a reading of time itself. The annual – and daily – increase in greenhouse gases is a literal chronology that translates into a corresponding impact on living and dynamic materials all over the world. One could also say it’s a countdown – for the species that are becoming extinct and for our civilization, in which we have become accustomed to progress but are increasingly needing to measure our time in losses. The French geologist who proposed the new postglacial era couldn’t have dreamed of anything like this in even his wildest imagination. Nor could he have imagined that only a few decades after the introduction of the Holocene, another new epoch, the Anthropocene, would be discussed to signify mankind’s domination of the elements. Including snow. Since the death of Okjökull, several similar memorial ceremonies have been held. A month later, in September 2019, a few hundred mourners, dressed in black, gathered at an altitude of 2,700 metres at what had been Switzerland’s Pizol Glacier, in remembrance and to bid farewell. Only an area the size of a couple of football pitches remained of the Swiss glacier near the border with Austria and Liechtenstein. ‘We’re here to say goodbye to Pizol,’ said glaciologist Matthias Huss, to the sound of long alphorns. ‘We estimate that five hundred glaciers have vanished from Switzerland since the 1850s,’ he continued, adding that the deglaciation has been dramatically fast. ‘Pizol has lost 80– 90 per cent of its surface since 2006.’

In August 2020, it was time to mark the passing of Clark Glacier in Oregon. This took place outside the State Capitol building in Salem, a monumental Art Deco-style edifice

with a white marble facade. A dark coffin containing some of the glacier’s last meltwater was brought there and stood in stark contrast to the pale stone. The aesthetic was inspired by a photograph of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the human rights lawyer and United States Supreme Court justice, who at the time had just been lying in state at the US Supreme Court in Washington, DC . Ginsburg had often adorned her black judges’ robes with a white lace collar. Mourning clothes, but also the image of a mountain with its glacier. Ginsburg, a national heroine known for her judgement and compassion, left her mark on the mourning ceremony for a glacier in Oregon, on the other side of the great continent.

The glacier was named after explorer William Clark, who, along with Meriwether Lewis, crossed the continent to the Pacific Northwest at the directive of President Thomas Jefferson, as part of an expedition lasting more than two years to map the central and northern parts of the present-day United States. These lands had become the property of the United States through the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, when it bought these vast territories from France. Much later, Lewis and Clark each gave their name to a glacier on the Cascade mountain range in Oregon. On maps dating from the 1900s and well into the 2000s, you can see the two white surfaces with their underlying blue elevation contour lines. Satellite images from 2020 show the new reality. Of the Clark Glacier, which has greater exposure to the sunnier south-west, only isolated fragments remain. Even the once-continuous Lewis Glacier, despite having a more advantageous position in the north-east, is now shrunken and in separate pieces. Doomed to die. Everything frozen melts.