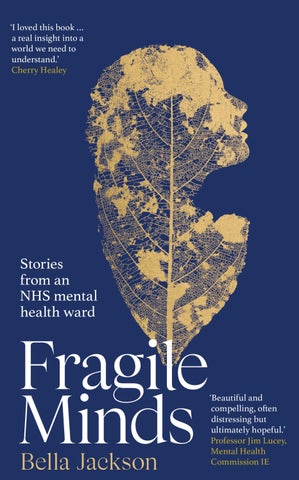

fragile minds

Fragile Minds

bella jackson

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published in Great Britain in 2025 by Doubleday an imprint of Transworld Publishers

Copyright © Bella Jackson 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

As of the time of initial publication, the URLs displayed in this book link or refer to existing websites on the Internet. Transworld Publishers is not responsible for, and should not be deemed to endorse or recommend, any website other than its own or any content available on the Internet (including without limitation at any website, blog page, information page) that is not created by Transworld Publishers.

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset in 12/15.5 pt Minion Pro by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9781529939774

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

For everyone with a story

To the thinking mind, which sinks its anchor in the past and future where no anchor will fix, tell this: no things are fixed.

– Samantha Harvey, The Shapeless Unease

Author’s Note

This book has been pieced together from scattered notebooks and scribbles on hands. Scribbles that became long emails to tutors, initially as an attempt to complain, then explain, then just to document.

I have written with the guidance and support of ex-patients, psychiatric survivors and mental health practitioners. The stories I tell here are based on real situations, though the patients, staff and settings are composites and I have gone to some lengths to obscure their identity, changing names, physical details, timelines and histories.

The health care professionals and settings reflect some of the attitudes and approaches of some of the people I encountered during my training. I have given people names to make them come to life but they do not represent or reflect any actual single individual or place of work.

I hope I have done justice to the individuals and their families, and that these stories help amplify the voices of both the rebellious staff and those people who are silenced by their labels – ‘disordered’, ‘dysfunctional’ or ‘ill’.

I’m aware that I only tell some stories and omit others, that all stories told bear counterbalancing occurrences. I am not refuting those. In the act of recording, I am being biased. I’m

showing only a fraction of the whole. But a finished quilt is made from many patches – clashing, partnering, vibrant, faded. Each a unique moment, needing to be acknowledged and remembered.

1

The Door

The three- storey building that housed the Acute Psychiatric Ward squatted beside an industrial estate. It looked insignificant from the outside, a blocky, creamcoloured structure with a fresh blue and green sign: Centre for Mental Health Care. As I turned off the pavement towards the sliding entrance doors, a raised bed filled with yellow flowers protruded into view. At its centre, a shrub had been pruned into a lopsided sphere.

It was my first morning on placement as a student mental health nurse. Learning on the job would make up a large portion of my two-year postgraduate training, with university days threaded throughout. The course had started in the classroom three weeks earlier, via introductions and welcome material. To my surprise, I found myself having to articulate to myself as well as to others why I was there.

Why was I there? I’d been working in social care for five years and though in many ways this step seemed like a tactical career move, it very much felt like a venture into the unknown. In previous jobs I’d worked regularly with

people in mental distress struggling with panic, anxiety, loss. Yet ‘mental illness’ felt perplexingly delineated from both my life and my work. It existed just out of reach: the clients who were assessed and swiftly directed off elsewhere, the voyeuristic documentary on TV, a garish headline in the newspaper, a man on the bus talking to his reflection in the glass. It seemed perceptible yet frighteningly undefined. Nebulous, it loomed over me; a presence I couldn’t shake. What I needed, I reasoned, was to understand. To open all the doors into psychiatry and stand right up close to the people within.

The reception area was empty. It looked like any other hospital waiting area: rows of plastic chairs, magazines, innocuous prints of flowers on the walls. I had been expecting something more otherworldly.

A bulky man behind the reception desk was watching me expressionlessly. He nodded.

‘Can you sign in?’ he asked.

I gave him my details and printed my name on the staff sheet, my heart thudding steadily.

‘Wait,’ he said, gesturing to my lanyard. ‘Is this quick release?’

‘Quick what?’ I replied.

The man stared at me. ‘I’m going to pull this,’ he said, as if explaining to a child. He clasped the strings around my neck.

‘To check it, OK?’

‘OK,’ I said, unsure.

He gave a short, sharp tug and the lanyard snapped off cleanly. He handed it back to me.

‘Good.’ He turned to his computer. ‘You can go in now.’

His large forearm directed me towards the corridor behind him.

‘Right,’ I replied, still gripping my lanyard. ‘Thank you.’

I followed the corridor, reclipping the loop of fabric around my neck and imagining the consequences of a lanyard that didn’t ‘release’. Some metres down, I stopped in front of a heavy, air-locked door with a large LCD screen above it. ACUTE WARD scrolled across in luminous, robotic text. Fire engine red. There was a keypad on the right. FOR ENTRY, a button declared in marker pen.

Through the panels of reinforced glass at the centre of The Door, I could see several people milling about in a stretch of hallway. One, a gaunt man wearing a baseball cap, looked at me and frowned enquiringly. Something tangled in my stomach. I can’t hesitate now, I thought, I’ve been seen. I pressed the button, my heart galloping, as the man began striding towards me.

When I was six, I locked myself in the bathroom.

My parents were having a house party, and every room was a jumble of legs. That’s how I remember it, as if I’d spent most of the night on the floor or under a table. The voices felt shrill and jarring, the movements of drunken limbs unpredictable and frightening. Someone fell in the pond. The air in our tiny flat was heavy with smoke. I remember crawling around shoes, gripping two of my favourite things in the world: a Sylvanian Families bear and a Kylie Minogue cassette tape.

At some point, I retreated to the bathroom. The stripped wooden door had a chunky iron lock with one of those

old-fashioned ornate keys. I turned it smoothly, hearing it click into place, and felt a sense of power, of control. The sound of bass and laughter was dampened there, the unknown adults just shapes moving past the peculiar stained-glass window: I was safe. I had a space which belonged to me, an interlude to verify and identify what I was feeling. Like a pair of lungs expanding, I felt giddy with relief. Locked doors can offer such freedom. After some time playing in the empty bath with my bear, I stood rejuvenated at the door and clasped the cool iron key. I turned it, and nothing. I tried again, but the door remained locked. Again and again. I can remember the heat flooding my face, my stomach hollowing. In my panic, I didn’t think to bang on the door. Didn’t want to draw attention to myself, in case I was ignored. That would have been too much to endure. So I stood there for ever, it seemed, turning that key. My hand aching, my ears buzzing with blood. I was crying, shaking. While everyone continued as normal outside. Maybe, I reasoned, they knew I was there, had somehow locked the door from the other side. Maybe they wanted me out of the way – it was easier without a child getting under their feet.

When it finally opened, I was despondent with fear and my fantasy of rejection. I was free, but remained abandoned. Just like that, all power had been taken from me, and no one had come to my rescue.

The gaunt man was intercepted by a woman with elfin-short hair and glasses, a nurse’s lanyard around her neck. She

pushed her body between his wiry frame and The Door. I heard her telling him in a muffled voice to step back, then again more sternly. The man took an almost comically large step backwards and grinned.

The woman turned, her teeth catching the light as she smiled.

‘You’re early!’ she pronounced, opening The Door just wide enough for me to slip through. ‘I like early people.’

Her accent was soft and lulling, the cadence resting on the first syllable of each word.

I offered the calmest greeting I could manage, while attempting to avoid eye contact with the man peering over her shoulder. She too ignored him and closed The Door behind me. It moved heavily, wading through the warm air before clicking into the frame.

It’s easy to walk in and out of a locked ward and forget the significance of that power. Does The Door protect the vulnerable people inside from the unkind world? Or does it protect our fragile society from the people who embody its failings? Perhaps, neither and both are true. What is true, is that having mastery over that portal tugs at many conflicting feelings. Of relief, of self- importance, pride and shame.

‘I’m Ray,’ the woman said, ‘I’m a staff nurse here.’

I followed her down the hallway, the man sloping beside us like a concierge. Slowing, I rebuked myself for ignoring him and caught his eyes hesitantly.

‘Hi,’ I said, introducing myself.

He echoed me, replacing my name with his own. Hodi.

Ray was talking over him. ‘Well, well! Your first placement!’ she said. ‘This is a good place to start.’

She stopped in front of an office door, the glass obscured from within by a mangled venetian blind. As she sifted through a large bundle of keys clipped to her waist, I took the opportunity to look around me.

Four or five men stood apart from each other, watching us in silence. Looking back, I’m unsure if the ward really did freeze like this, or if it was only my perception of it. As if the only way I could take it in was to isolate everyone like pieces on a chessboard.

My tall acquaintance, Hodi, was the nearest to us. His eyes wide enough to display shock, his willowy eyebrows arching around them. Yet his droll, grinning lips seemed to betray the other features.

Over his left shoulder was a small, heavily stooped man wearing dental-green hospital pyjamas, the bottom half of the ensemble hanging perilously low below his waist. He appeared to be leaning forward on to the balls of his feet, his arms pendulous away from his body, his face a tired waxwork. A flicker of drool hung from the browned front teeth in his open mouth, his eyelids half-mooned and flaccid. I guessed him to be in his late forties, though I later found out he was just thirty-one.

I put up my palm in awkward salutation. The man’s eyes followed my hand steadily, but his face remained unchanged. Somewhere within his throat a rush of air curled upwards. Reaching his tongue, it formed a guttural, gurgling reverberation. A slow smile pulled across his face, as if amused by his own incoherence. Then on cue, his trousers slipped down to

his protruding knees and hung there. The man continued to sway, his eyes fixed on mine.

The key had been found.

‘Come in and put your bag down,’ Ray declared, breaking my trance-like state.

‘Yes,’ I said reflexively, my body following her into the room. ‘Jack, pull your trousers up,’ she instructed to the closing door. The other men remained shapes against the blank walls.

*

I have avoided writing about Jack for years; his story still haunts me. My mind often wanders to him, before sharply retreating, like the sudden horror of swimming over an abyss. But I will get to Jack.

*

In the office, Ray explained her role to me. She was mostly kept busy running things behind the scenes, writing up reports for tribunals, organizing admissions and finding staff to cover shifts. But she was still the ‘key nurse’ for three patients, and said she’d keep an eye on how I was doing.

I handed her my placement booklet and she flicked through the tasks I’d need to complete to qualify. Reading the list at university, I had been surprised by their basic nature. I had to be signed off for such pleasantries as being ‘non-judgemental, respectful and courteous at all times when interacting with patients and colleagues’ and being ‘able to work effectively within the inter-disciplinary team to build

professional relationships’. There were more practical tasks to check off too, such as administering medication, taking accurate vital signs, remaining aware of patients’ care plans and demonstrating a knowledge of pharmacology. Nurses largely learn their craft from those around them and, as a staff nurse, Ray would play a crucial part in this.

‘So . . .’ She lingered on the word, watching me. ‘You’ve got a background in social care and counselling?’

I nodded keenly, explaining my various jobs and courses. As we talked, Ray smiled broadly, though her interjections were clipped – as if she hadn’t the space in her day for elaborate sentiments – and I felt more scrutinized than reassured.

She closed my booklet and peered at me again. Unsure what she was hoping for, I asked about the number of patients on the ward.

‘Twenty-two,’ she replied, ‘and they’re all very ill.’

Before I could respond, she clapped her hands together, making me jump.

‘Oh yes! We’re always at full capacity here.’

She explained that some patients were there ‘by choice’ –otherwise known as informal admissions – some were detained under Section 2 of the Mental Health Act for twenty-eight days, some on Section 3 for up to six months, while others had been there over a year.

‘We’ll go through everyone later,’ she said, waving the words away. ‘You have a wander round and get a feel for the place. Stay within the hallway and day area. Don’t go into any bedrooms alone.’

My head was swamped with questions, but I didn’t want to look as though I was stalling for time.

‘Oh, and there’s a psychology group today you should join,’ she continued, swivelling slowly from side to side in her chair.

‘That would be great!’ I enthused, reiterating how interested I was in psychological treatment.

Ray squinted through her glasses at me. ‘Look . . .’ she said. ‘You’re in nursing now. Nursing is about recording and passing on information. Leave the psychology to the psychologists. Your number one role is to keep people safe. If everyone is alive at the end of your day, then you’re being a good nurse.’

When I left the office, Hodi, Jack and the rest of the shadow men had gone. Instead, a lone man with a rough beard and greasy hair was pacing towards me. His head curling forward to face the floor, hands knitted together, his feet making no sound on the lino, like a pensive ghoul.

I watched him getting closer, wondering what to say, which way to move, but at the last second he steered around me as a boat avoids a sunken rock. On reaching The Door, he turned fluidly on his heels and started back the other way. This time I managed a ‘Hello’.

Several seconds of silence followed as he continued to move away from me. Then, as if my words were a long stick prodding him in the side, the man flinched and looked up with a startled expression.

‘Hello?’ he asked, his forehead creasing.

And then he was gone, his headless silhouette drifting down the hall.

I decided to get my bearings from somewhere I could stand without looking too conspicuous and headed for the ward’s reception area. On my way, I passed a large, glass-fronted

room I would come to know as the beehive. Inside, staff members in plain clothes, discernible by their blue lanyards, milled about and chatted. Mental health staff now rarely wear uniforms. This informality is said to aid discreetness when working out in the community, and encourage engagement and trust on wards.

The reception desk was empty, and I hovered behind it, busying myself with reattaching pens to clipboards which had been glued down to the tabletop. On the wall behind the desk I noticed a rack of haphazard, yellowed leaflets and picked one up. Risperidone – an antipsychotic, it said. Do not take this medication with alcohol or ‘street’ drugs. I’d never heard of risperidone, and turned the leaflet over in my hand. It is usually safe to take risperidone, it continued, but it’s not suitable for everyone. More than one in ten people might get these side effects – headache and movement disorders including tremor, shaking, spasms, problems with speech, unusual movements of tongue, face or other parts of the body that you can’t control. I looked up. Wait, I thought – more than one in ten? I picked up another leaflet, on benzodiazepines, drugs used mostly for treating anxiety and insomnia. More than one in ten people might experience side effects of anxiety or agitation, confusion, loss of memory, or dizziness, I read. Something uncomfortable moved through me.

I shook the feeling off. OK, I thought, I need to be active, I need to go somewhere.

Around me, bedroom doors were beginning to creak open and drowsy-looking patients were appearing in the hallway, their eyes and lips gummy with sleep. After squaring the

leaflets for a fourth time, my heart thudding, I rounded the reception desk and began making my way back to the office to feign some sense of purpose. On my right I passed a large room with the words DAY AREA printed across the open door. Inside, a meandering line of patients was forming for breakfast. A few faces looked up at me blankly.

This is stupid. Just go in. Talk to someone.

I turned and walked into the day area as slowly as I could. A nurse in a crisp white shirt stood just inside the door, a ring of keys secured to his trousers. He smiled at me and nodded, before looking away. I introduced myself, which he seemed to find amusing. ‘Yes’ was all he said.

I watched the line of patients murmuring and swaying amorphously.

‘Hey!’ The nurse moved rapidly towards the mass of bodies, his arms flapping. ‘Stay in a line!’

A patient in a leg brace glared at him. ‘Fuck off,’ he said pointedly.

This doesn’t seem like the right time to be here, I told myself. Maybe I’ll just go back to the office and read some notes.

I left the room feeling stiff and pathetic, listening to my new nursing shoes squeaking against the floor. As I turned the corner, The Door and reception desk came back into view. Several patients were now stood around it, their backs to me. One squat, heavy-set man was facing The Door, his body mirrored in the glass panelling, his shaved head glinting under the strip-lights.

A nurse navigated his way around the other patients, before stopping next to him.

‘Saul,’ I heard him say. ‘Saul, can you move away from the door?’

Saul said something I couldn’t hear.

‘Saul,’ the nurse said again in a scolding tone. He put his arm on Saul’s and tried to guide him backwards.

Saul shook it free. ‘I’m fine here,’ he said loudly.

‘Look . . . If you don’t want your medication, you’ll become unwell,’ the nurse said. ‘Why do you want to see the doctor? You can talk to me. ’

Saul laughed. ‘Hah! Thanks, but no thanks,’ he said, still staring at The Door.

Ray appeared, her arms crossed over her chest. ‘What’s going on?’

The nurse threw up his hands and backed away.

Saul, an East Ender in his late forties, turned to look at her. His face was a deep burgundy, sheened with sweat. There was a tiny, basic mobile phone in his hand.

‘I should be respected, that’s all I ask,’ he said.

Ray angled her head. ‘OK,’ she replied, ‘you’re being respected. Why are you waiting by The Door?’

‘I already told him,’ Saul said, gesturing to the nurse who was now leaning against the wall a few metres away. ‘I want to talk to the doctor about my meds. That’s all I fuckin’ ask. I WANT to TALK to him.’

Ray smiled. ‘Can you talk to me instead?’

Saul started jabbing at the phone with his large hands. ‘I’m callin’ my lawyer if I can’t talk to him. I’m not fuckin’ pissin’ around.’

‘OK, Saul,’ Ray repeated. ‘But you can wait for him away from The Door. You’ll be called if it’s your time for ward round.’

Saul turned and pushed through the other patients, barrelling past me.

The leaning nurse raised his eyebrows and chuckled as he passed.

There was something so unusual, so confusing, about seeing a person in such a heightened emotional state faced with someone so apathetic.

I watched Saul go into his bedroom momentarily, then he came out again.

‘Can someone other than this guy speak to me?’ he pleaded, gesturing with his chin towards the chuckling nurse.

I looked around. Ray had already gone back down the hallway to the office and closed the door. All the other nurses were visible in the beehive, but just out of reach.

‘I can – can speak to you,’ I said, a little too formally.

I moved towards him, wondering if I was going to be rejected or shouted at as an unknown, a person with clearly no power at all. But Saul nodded, business-like.

‘Thank you,’ he said.

‘Are you . . . OK?’ I asked, feeling immediately idiotic.

‘Fuckin’ . . . no. No,’ he said under his breath, ‘I’m not OK. It’s ward round today, but I can’t remember if it’s my day or not, and no one will fuckin’ tell me so I can prepare . . .’

Had I missed something? The request seemed straightforward enough.

‘Should I ask for you?’

‘Yeah.’ He nodded. ‘That would be nice.’

I turned from him.

‘Hey!’ Saul’s raised voice echoed off the walls. I spun back round. ‘Who are you?’

‘Oh, sorry,’ I said. ‘I’m just a student nurse.’

‘Right. Right.’ He began jabbing at his phone again. ‘Hello student nurse.’

I asked in the office. It was not Saul’s day to meet with the consultant – or ‘ward round’ as they called it here.

‘Well fuckin’, fuckin’ great. Great!’ Saul yelled when I told him. ‘It’s never my turn is it? I have things to say to him. I have things I want to change about my medication. No one fuckin’ listens in here . . .’

A slender, sharply dressed man in a cardigan pushed through The Door and slipped lithely into an office. Dr Oxley, one of the psychiatrists. Saul leapt past me, his phone swinging at his side.

‘Doctor!’ he yelled. ‘When am I seein’ you, doctor? I have something to say to you! When am I gettin’ out ?’

He turned to face The Door to the outside world and then to the doctor’s office, as if deciding which one to pound on first. He chose the office door. The palm of his hand slapped quickly and incessantly, before winding down to a slow, desperate thump. He paused, waiting.

‘Fucker!’

The extreme anxiety around meeting the consultant could be felt by talking with any of the patients. Some spent hours hovering around The Door trying to catch him as he flitted in and out, always with somewhere else to be.

That day there were two other patients waiting for him alongside Saul. One looked glum, the other panic-stricken.

‘All right guys,’ Saul said, gathering the men conspiratorially.

‘I don’t think we’ll be gettin’ anywhere with Fuck Head today, so go get a coffee or somethin’.’

Saul and I talked in the hallway for some time, his eyes darting back and forth between me and the office.

‘When people don’t speak to you in a normal way,’ he said, ‘don’t give you respect, it makes you feel sort of inhuman, you know? It’s hard to explain . . .’

He tightened his grip on his phone and I worried he would crush it.

‘The doctor, all he ever asks me is “How are you feelin’ from one to ten?” It’s fuckin’ ridiculous! He gets paid a lot for doin’ that. That and fuckin’ druggin’ me up with five different meds. Good job I’ve got a sense of humour.’

A middle-aged man with no front teeth joined our conversation. ‘Yeah!’ he added, flicking a lock of hair from his face. ‘Thing is, prison’s better than here. At least with prison you do your time, or less. Then you leave . . . you know when you’re getting out. Here they can keep you for ever, no idea for how long.’

Saul was nodding. ‘That’s true! My cousin is out now and he’s the most violent man I know. He stabbed two people but they let him out real quick, and now everyone leaves him the fuck alone. No one’s stuffin’ pills in his face. But I’m still locked up, cos I’m mental . . . But I never hurt no one. It’s not fair.’

After some time, Dr Oxley reappeared, heading at speed towards The Door.

‘Doctor!’ Saul yelled after him. ‘Do you care about people’s feelings, doctor? Do you care about anyone?’

Dr Oxley, still propelling forward, looked over his shoulder. ‘I hope so!’ he exclaimed. And in a second he was gone, The Door closing firmly behind him.

‘Bastard!’ Saul screamed through the glass.

*

The longest you can be held in a UK prison before being taken to court is fourteen days, which only applies to arrests made under the Terrorism Act. Otherwise, a suspected criminal can be held for twenty-four hours, which can be extended to ninety-six hours if the crime is very serious. This is unless you’ve ever been convicted of a crime in the past, in which case you’re likely to be held on remand in prison for up to six months. With suspected mental health conditions, a person can be detained against their will under Section 2 for an initial twenty-eight days for assessment. If it’s decided you have a mental disorder and you’re deemed ‘at risk’ to either yourself or others and you’re not agreeing to the treatment advised, you can be detained for a further six months under Section 3. There is no limit to the number of times Section 3 can be renewed.

When I’d read about the different sections during our introductory weeks, they’d sounded thorough to me, and I’d given them little further thought. But the reality of seeing people confined by these legalities was striking. On a page, the protocols are just cold numbers. In the flesh, the fear and anger that emanates from them is palpable.

*

Later that afternoon, I joined the psychology group Ray had recommended. I was introduced in the hall to Davina, one of the two hospital psychologists. Davina was very thin; her skin looked stretched over her bird-like skull, her glasses balanced on the tip of her nose.

‘Come in with me, no problem,’ she said, clutching a clipboard to her chest.

There were six of us in the group: Davina, three patients, a trainee psychologist and me. I sat quietly with a pen and paper, and the workshop on Positive Thinking began.

‘Today we are going to think about positivity and imagination,’ Davina declared. ‘We are going to consider how the way people with healthy minds get along is that they are able to say “Yes” to challenges and opportunities that arise, rather than people with disturbed minds who cannot do this . . .’

My body became rigid. I looked around the circle. Disturbed minds? The trainee psychologist sat placidly, her eyes fixed on Davina.

‘Now,’ Davina continued, ‘shall we introduce ourselves?’

Her eyes rested on a fidgety, rotund man staring at the floor. Vern presented himself dutifully, telling us his name and diagnosis: paranoid schizophrenia. He nodded rhythmically as he spoke, his expression empty. Beside him was the pacing man I’d seen when I first came in.

‘Schizoaffective disorder’ was all he said.

There was a pause.

‘And your name?’ said Davina.

There was another pause. The man stared at her in silence.

‘OK, fine.’ Davina shook her hair as if an insect had landed there. ‘And who’s next?’