NIGHT LIFE

Also by John Lewis-Stempel

Meadowland: The Private Life of an English Field

The Secret Life of the Owl

The Wildlife Garden

Foraging: The Essential Guide

Fatherhood: An Anthology

The Autobiography of the British Soldier

England: The Autobiography

The Wild Life: A Year of Living on Wild Food

Six Weeks: The Short and Gallant Life of the British Officer in the First World War

The War Behind the Wire: Life, Death and Heroism

Amongst British Prisoners of War, 1914–18

The Running Hare: The Secret Life of Farmland

Where Poppies Blow: The British Soldier, Nature, the Great War

The Wood: The Life and Times of Cockshutt Wood

Still Water: The Deep Life of the Pond

The Glorious Life of the Oak

The Private Life of the Hare

The Wild Life of the Fox

The Soaring Life of the Lark

The Sheep’s Tale

La Vie: A Year in Rural France

Woodston: The Biography of an English Farm

England: A Natural History

Night Life

Exploring Britain’s Wild Landscapes After Dark

John Lewis-Stempel

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published in Great Britain in 2025 by Doubleday an imprint of Transworld Publishers 001

Copyright © John Lewis-Stempel 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset in 11/14.5 pt Goudy Oldstyle Std by Six Red Marbles UK, Thetford, Norfolk Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 9781529938159

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

To Tris, Freda and Penny. The night belongs to those who love it. You.

Contents

Introduction: Fear and Loving of the Night 1

Part I: Silent Night 9

Part II: Wandering Lonely 31

Part III: Around the Barley Field and into the Summer Wood 53

Part IV: Tideline 79

Part V: Slivers of River 99

Part VI: Wolf Moon 113

Night Tracks: Nocturnes for Nature-lovers 127

Appendix: The Moth Garden 131

Envoi: ‘Good-Night’ 139

The Starlight Night

Look at the stars! look, look up at the skies!

O look at all the fire-folk sitting in the air!

The bright boroughs, the circle-citadels there!

Down in dim woods the diamond delves! the elves’-eyes!

The grey lawns cold where gold, where quickgold lies!

Wind-beat whitebeam! airy abeles set on a flare!

Flake-doves sent floating forth at a farmyard scare!

Ah well! it is all a purchase, all is a prize.

Buy then! bid then! – What? – Prayer, patience, alms, vows.

Look, look: a May-mess, like on orchard boughs!

Look! March-bloom, like on mealed-with-yellow sallows!

These are indeed the barn; withindoors house

The shocks. This piece-bright paling shuts the spouse Christ home, Christ and his mother and all his hallows.

Gerard Manley Hopkins

Fear and Loving of the Night

Jesu Lord, blyssed thou be, For all this nyght thou hast me kepe From the f[i]end and his poste, Whether I wake or that I slepe.

Therelief of the medieval prayer-writer on seeing dawn is evident down the centuries. The uncertainties and phantasmagoria of the dark hours banished, done; the sanctuary of a brand-new day revealed by rosy-fingered dawn.

Achluophobia, lygophobia, nyctophobia, scotophobia – whatever you call it, fear of the dark night is as old as humanity. It is natural, an innate trepidation that stems from the time of the prehistoric mists when we were not, courtesy of technology, the apex predator that we are today. Humans rely primarily on the sense of sight, which is disadvantaged in darkness. Indeed, we are doubly disadvantaged since what night

vision we do have is relatively poor – unlike that of the big cats that prowl the African savannah.

Our fear of the night is an evolutionary survival trait. Ancestors who failed to stay safe in the deep, nocturnal hours died. Over the millennia, the nocturnal world became the repository of anxieties, which were rendered into personifications or supernatural/ unnatural beings. In Greek mythology the goddess Nyx, wearing a star-studded black robe, emerged from a cave to ride across the sky in a chariot pulled by black steeds. She was Night, and she was Death. The night, in the human mind, became the abode of sprites, goblins, witches and monsters. For years, according to the Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf, the ravening creature Grendel attacked the mead hall of Heorot, and consumed men unlucky enough to fall into his claws. Fear of the dark is fear of the unknown.

The Enlightenment and the streetlamps of contemporary civilization have all but banished fear of supernatural beings in the West. Few believe in sprites and elves any more. But the lights of the modern world have obliterated any meaningful connection to the night. We have lost touch with its wonders as well as its terrors. The Ancients may have fretted about malevolent spirits abroad in the dark, but did not gazing up at the stars cause them to think big, about God, the

workings of the universe, what it is to be human? For many today the natural night is truly the unknown.

It is the farmer-naturalist’s luck to work mainly outdoors and for long hours. And frequently into the dark hours.

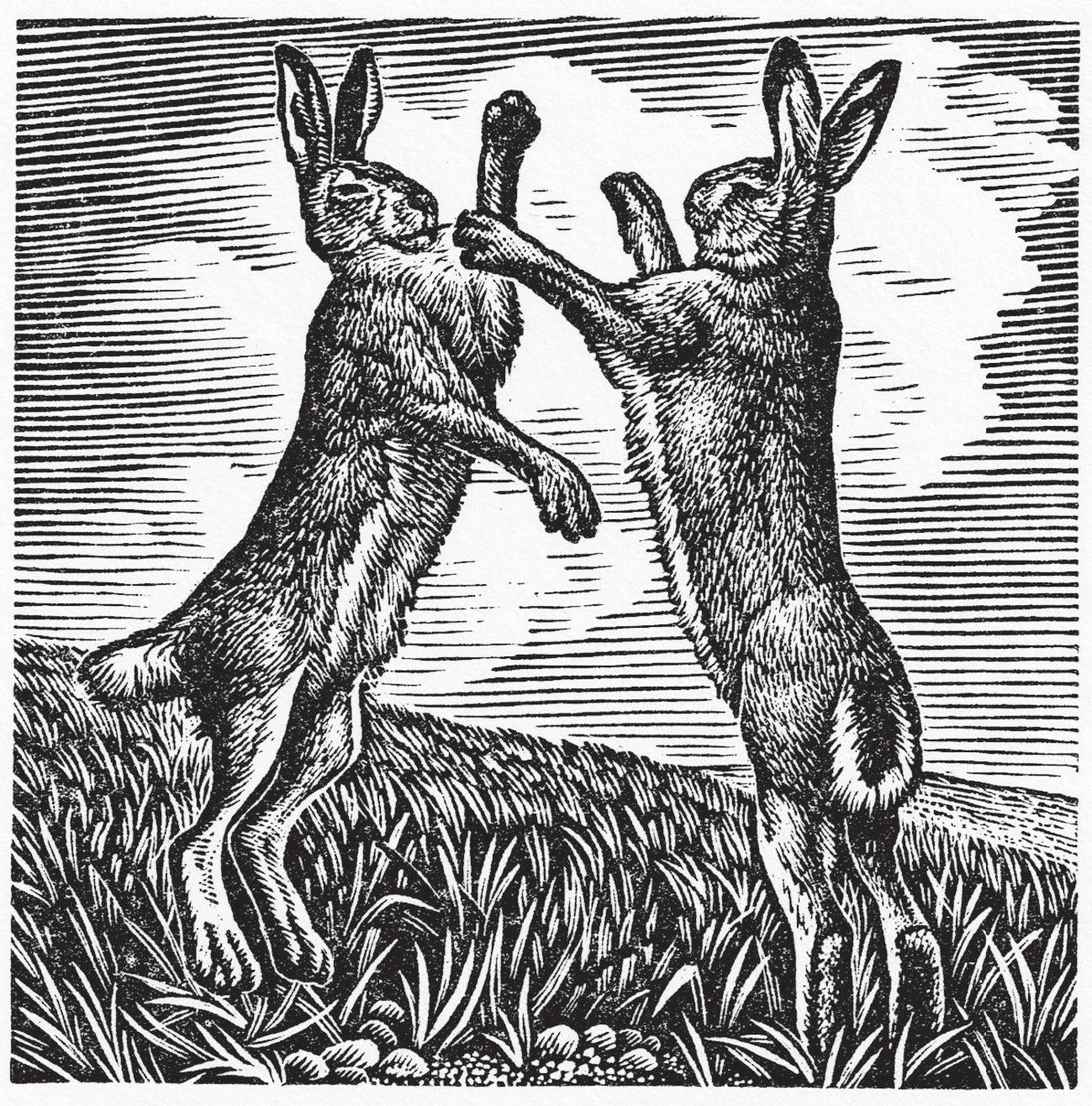

Like I did last night, a May night of a waxing moon and sweet with the scent of naked warm earth, greening grass, and spiced by the phosphorescent hawthorn blossom. I was late feeding the pigs, who do not like to be kept waiting at dinner time, and I had driven the tractor full throttle down to the wood, a sack of sow nuts and a Labrador sliding about in the metal transport box on the back. As I heaved the sack out of the box my peripheral vision remarked three hares ‘boxing’ in the field next door, where the moonlight gleamed on the freshly tilled soil. Spring moonlight has a different quality to winter moonlight; the night sky has unhardened, and the lunar beams are as gentle as caresses.

Prosaically, the boxing of hares is an unreceptive female fending off ardent males. Jill versus Jacks, a battle of the sexes. But hares at night always twist the scene, make the ordinary extraordinary. Such was the angle of the land that against the moon the hares were silhouettes, and up on their back legs the animals, with their flurrying arms, became human dancers. One hare

slumped down into an earthen clump, a sod, only to rise from the earth, born again. The night hares were brazen, their daylight timidities thrown away. I cannot tell you if they made noise in their pugilism; the purring of the tractor blanked all other sound. I was a spectator to a mime.

Watching the contorting hares, I understood why the people of the past likened boxing hares to a coven of tiny dancing witches. Or considered them, as partly nocturnal creatures, as belonging to the moon. I looked up that night and beheld the moon and saw, as people all over the world do, shadow-patterns in the shape of a hare. In Celtic myth Eostre changed shape to become a hare at the full moon; all hares were sacred to her and acted as her messengers. Small wonder, perhaps, that the Celts were so opposed to eating hare. Since hares, however, were heavenly messengers, it made sense – to the Celts – that they could be used as instruments of divination, by studying the patterns of their tracks, the rituals of their mating dances and details within their entrails.

These were some of my wonderings and recollections as I gazed at the trio of hares. The dog was less entranced and barked. The three hares evanesced, as fast as terror, as though they had never been. A witchy trick.

You will have got the point. The real creatures of the night are fabulously interesting, and the night allows imagining in a way that the ‘cold light of day’ does not. At night the senses become reordered – hearing becomes privileged over vision – an alteration to the human being that makes one more ‘animal’, more sensitive to nature.

This is my second book of nightwalks, a sequel to Nightwalking. Once again, I can be found in my