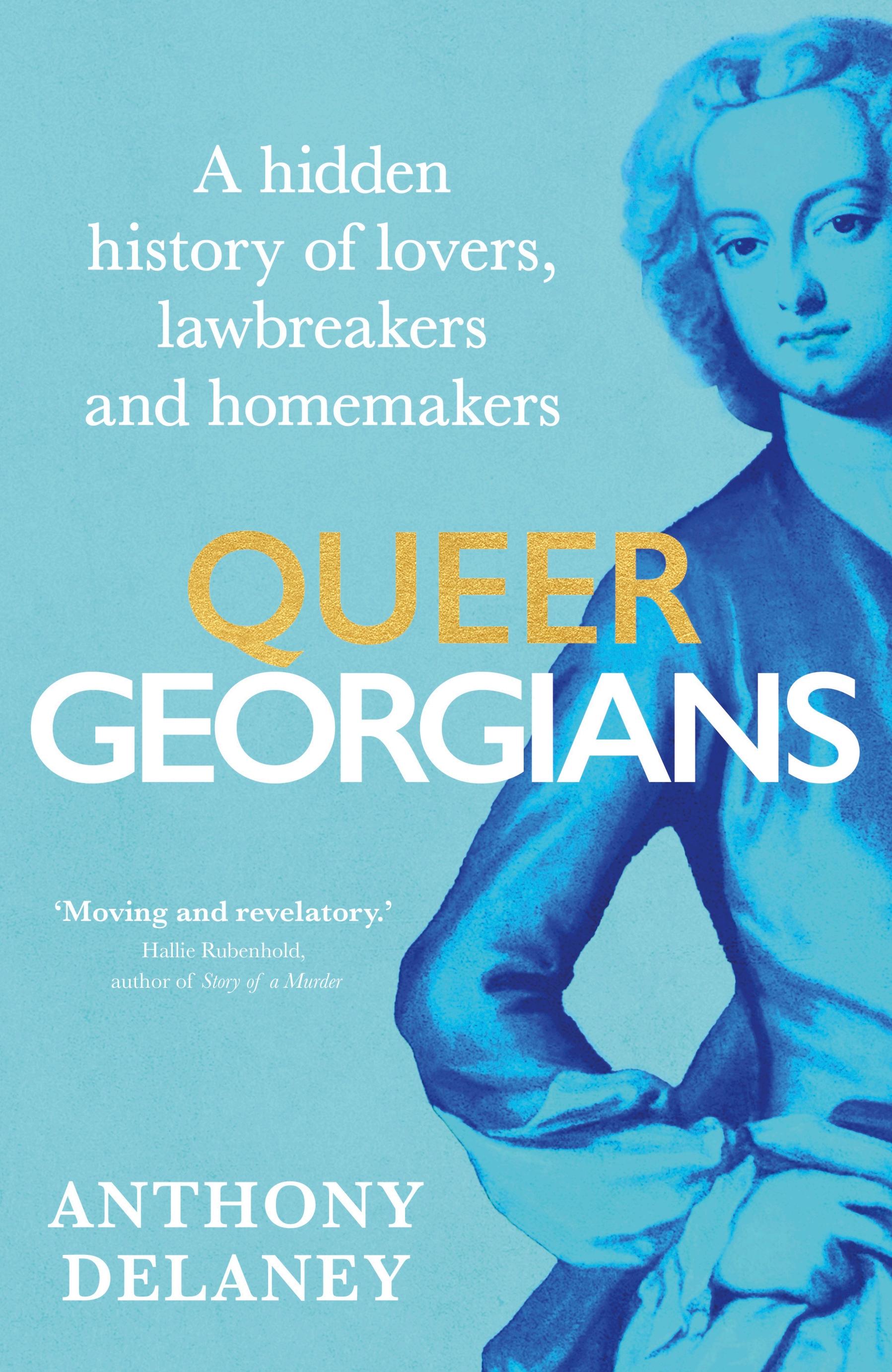

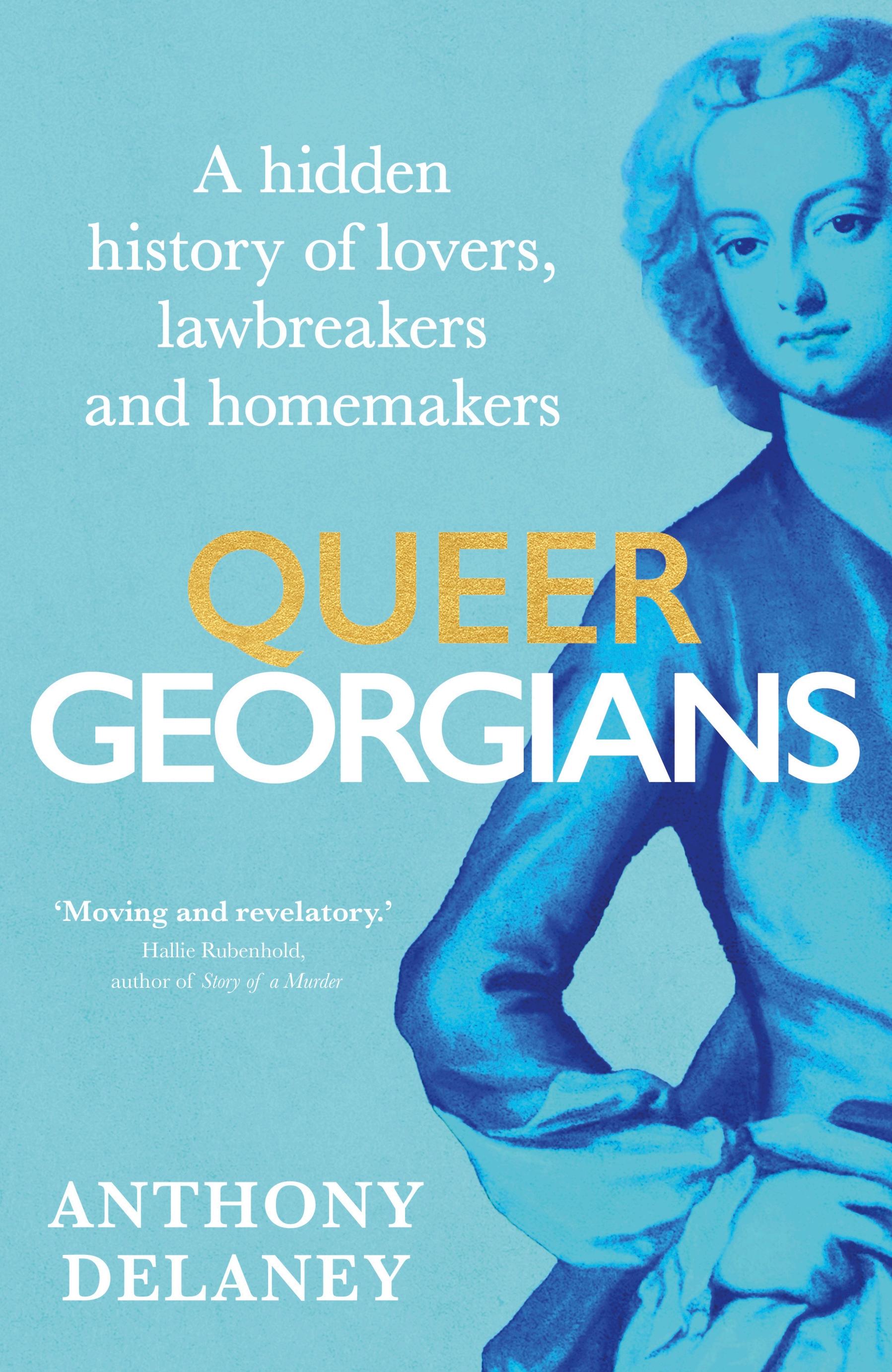

Queer Georgians

Queer Georgians

A hidden history of lovers, lawbreakers and homemakers

ANTHONY DELANEY

TRANSWORLD PUBLISHERS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London sw 11 7bw

penguin.co.uk

First published in Great Britain in 2025 by Doubleday an imprint of Transworld Publishers

Copyright © Anthony Delaney 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

As of the time of initial publication, the URL s displayed in this book link or refer to existing websites on the Internet. Transworld Publishers is not responsible for, and should not be deemed to endorse or recommend, any website other than its own or any content available on the Internet (including without limitation at any website, blog page, information page) that is not created by Transworld Publishers.

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset in 12.5/15.75 Dante MT Pro by Jouve (UK ), Milton Keynes Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN s:

9781529927689 (cased) 9781529927702 (tpb)

For Paul O’Grady (1955–2023)

Hellraiser, trailblazer, history-maker, friend.

‘Well, well, it looks like we’ve got help with the washing up.’

Lily Savage, 30 January 1987, as police officers raided the Royal Vauxhall Tavern, London.

Author’s Note

THE PERIOD EXPLORED IN this book (1714–1837) is foreshadowed by the introduction of the Marriage Duty Act (1695), which imposed punitive measures on bachelors who did not wish to, or could not, marry. It incorporates the continuation of the Buggery Act (1533), which sought to punish all sex acts beyond the procreative, but particularly targeted men who had sex with other men. This period also includes other pivotal moments in the history of gender and sexuality such as the raid on Margaret Clap’s molly house (1726), the introduction of Hardwicke’s Marriage Act (1753), and the raid at the White Swan on Vere Street (1810), a proto-gay bar. This book, therefore, looks at a time of significant ‘heteroregulation’ in Britain and beyond.

I coined the term ‘heteroregulation’ in its current context whilst writing my PhD to be used as an alternative to ‘heteronormative’.1 I reject the linguistic implication that there is a ‘normal’ (hetero) sexuality, counter to which others might be judged ‘abnormal’ and legislated against accordingly. There is nothing ‘normal’ about the heteronormative. Indeed, the term ‘heterosexual’ once implied an ‘abnormal or perverted appetite toward the opposite sex’, or

Author’s Note

a ‘morbid sexual passion for one of the opposite sex’.2 Instead, ‘heteroregulated’ better describes the deliberate social, cultural and legislative acts that were calculated to control and admonish minority groups across several centuries. That regulation continues today.

In its determined opposition to this regulation Queer Georgians is queer in focus and broadly adheres to the scholar Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s use of the term in Tendencies (1993). She argued that queer history is ‘the open mesh of possibilities, gaps, overlaps, dissonances and resonances, lapses and excesses of meaning when the constituent elements of anyone’s gender, of anyone’s sexuality aren’t made (or can’t be made) to signify monolithically’.3

There will be some who argue that applying the word ‘queer’ to the past is anachronistic. It is, but that’s how historians communicate their findings. The word ‘family’ does not mean exactly the same thing now as it did in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but experts talk freely about the history of the eighteenth-century family. I hear no objection when historians write about ‘heterosexual men’ in the seventeenth century; heterosexuality is seen as the normative positioning, an identity that needs no definition. Meanwhile, historians of gender and sexuality are tying themselves in knots trying to define and justify their use of the word ‘queer’. If we readily accept these anachronistic tendencies because they are the easiest way in which we might discuss a specific experience or idea in the past, then we must grant the same grace to the study of queer lives.

That said, beyond ‘queer’ I have largely refrained from applying modern identity categories to the histories that follow. Indeed, I suggest it is heteroregulation, not queerness, that has seen the formalization of various gender non-conforming identity categories in our own time. Once rigidly categorized, identity markers can be used to fracture and divide so that the most vulnerable

amongst us might be more stringently regulated. The Georgians had no need for such categories and markers, however, and so they are largely dispensed with here. In a similar vein, I refer to my protagonists throughout using the pronouns they used for themselves. Sometimes, tantalizingly, this changed depending on the day. The Chevalier d’Éon, for instance, refers to herself as ‘she’ approximately 55 per cent of the time, and ‘he’ 45 per cent of the time. I have followed his example.

Throughout this book you will encounter words and descriptions of people in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that sit uncomfortably with modern sensibilities. They are included here, however, as a marker of the time in which they were written or said.

Modern monetary values are provided alongside their eighteenthand nineteenth-century equivalents to give an indication of spending power. These equivalents have been calculated using the Bank of England Inflation Calculator.

Prologue

WE HAVE NO HI s TORY . The queers, I mean. That’s what they say, anyway. Sure, there was the upheaval of the Stonewall riots in New York and the administrative quagmire that was the Wolfenden Report in the United Kingdom, but these are very modern concerns. Not real history. These things are, some argue, the result of a liberal bias, fuelled by an elite mainstream media which has been morally corrupted by ‘the gay agenda’. Besides, how can anyone write a history of Georgian queerness when homosexuality wasn’t even ‘invented’ until the latter half of the nineteenth century?

On 6 May 1868, the Hungarian journalist Károly Mária Kertbeny drafted a letter to Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, a German lawyer and activist who campaigned for the rights of same-sex-attracted men. In his letter, Kertbeny attempted to categorize sexual experience, rather than sexual identity, and so left us with the first recorded occurrence of the word homosexual. From there, homosexual and its derivatives took on several profound medical, legal, social and cultural meanings. Perhaps, then, there really is no legitimate way of writing about

queer histories prior to 1868? What words would we use when our ancestors didn’t have the same language by which to understand themselves? Certainly, the vast majority of LGBTQIA + history pays homage to our twentieth-century forebears. By then, the queer archive had been preserved in a more deliberate and transparent fashion. But queer histories run much deeper than this and significantly predate the invention of homosexuality in 1868. As such, though it is true to say that the language used by our queer ancestors to describe their gender identities and sexual experiences may differ from our own, they are no less queer for that.

So why do the queer Georgians deserve special attention? And why do they demand that attention now? As a historian I spend a lot of time in various archives, poring over details of broken hearts that have long since stopped beating, or imagining the frustrations of a writer whose ink I find splodged unceremoniously across her delicately crafted correspondence. My research interests have predominantly been drawn to the ‘long eighteenth century’, often referred to as the Georgian period in Britain and its colonial territories.1 Despite huge popular focus on the tempestuous Tudors and Stuarts (1485–1714) and the dour Victorians (1837–1901), the Georgian period was foundational to the ways in which we understand the world today. Not to mention altogether more thrilling than either, and more than just a little bit camp.

The Georgians were asking many of the same questions about gender, sex and sexuality that we are today: What makes a man? What is a woman? What exactly was the ‘Third Sex’? And what did that mean for the other two sexes? Although few attempted to answer these questions definitively, there are clues to their attitudes, ideas and personal experiences littered throughout various primary-source documents if you know where to look. The first of these appeared to me in the homely form of a ‘cotquean’.

I initially encountered the term whilst in the informationgathering stages of my PhD. In the brilliant Behind Closed Doors (2009), historian Amanda Vickery briefly mentioned this type of gender non-conforming man in her exploration of ‘The Trials of Domestic Dependence’:

Conduct books prated that the management of all things interior fell to the mistress. In popular culture men who meddled with domesticities were disparaged as ‘cotqueans’, while ballads sniggered at the chaos unleashed by interfering husbands.2

And that, essentially, was that. Despite my best efforts, I could find no other substantial reference to the cotquean, who seemed to me a potentially queer figure, in any history books. So I set about gathering as much new evidence as I could to help uncover this forgotten history.

Over the next three years I discovered that the word ‘cotquean’ comes to us from early modern French, ‘quean’ meaning woman (a sense that has recently been repurposed, viz. ‘Yasss Qween!’) and ‘cot’ or ‘cote’ denoting house or hut.3 Though the word ‘cotquean’ has fallen out of use today, it was widely known in the eighteenth century. Everyone from hawkers to duchesses would have used it and understood the cotquean to be ‘a man who busies himself with women’s affairs’.4 Amongst his other ‘feminine’ domestic traits, such as sewing, interior decoration and hosting, the cotquean was reportedly ‘endowed with the Gift of tossing of Pancakes, and had a wonderful Knack at tempering the Materials of a Bag-pudding’.5

However, because of his domesticated ways this effeminate man was to be excluded, some contemporaries believed, from two important institutions: politics and marriage.6 Further, in a

striking section from an anonymous eighteenth-century pamphlet snappily entitled Satan’s Harvest Home (1749), it was stated that the cotquean was explicitly understood by Georgians as a man who had sex with other men.7 Here I had encountered a male ‘type’ who was blatantly linked to same-sex activity in the premodern past. The cotquean was, as I had suspected all along, very queer indeed.

Forgotten details such as this show us that gender, sex and same-sex desire was a much more complex and deep-rooted historical experience than many experts have previously imagined. Naturally, this discovery then posed another pressing question: if the cotquean had been forgotten or, indeed, deliberately obscured from our history, what else had we missed? What other parts of the queer past had been taken from us, misinterpreted, or lay safely secreted between the pages of a dusty old diary, waiting to be rediscovered? And so I dug deeper, read between the lines, and eventually set about reclaiming a lost history.

As the years went by, a motley crew of politicians, sex workers, aristocrats, milkmen, landowners, spies and labourers emerged from their archival obscurity to occupy my every thought and (I hope) to enliven these pages. They are the queer Georgians, and it is my privilege to introduce some of them to you across the next eleven chapters.

Our narrative begins with a Londoner in 1726 and ends with a New Yorker in 1837. In Chapters One and Two, a milkman named Gabriel Lawrence pulls back the curtain on a secretive gathering of men overseen by the indomitable Margaret ‘Mother’ Clap. Here be the London mollies, a riotous group of working-class men who were attracted to other men. However, these mollies had caught the attention of London’s moralizing class, and the relative safety of their underground network was about to come

crumbling down around them. Inevitably there was heartbreak in what followed, and together we will track the ‘sodomites’ route’ through the disease-ridden and corrupt Newgate Prison before finding ourselves underneath ‘the three-legged mare’ of the gallows at Tyburn. Despite this, something altogether more defiant emerges from the violent chaos that Gabriel Lawrence found himself caught up in. This is also a history of a queer community forged with safety, succour, security and sex in mind.

Chapters Three and Four tell a love story. They examine the shared history of John, Lord Hervey and Stephen (Ste) Fox, whose relationship blossomed in the years following Gabriel Lawrence’s demise. As members of the aristocracy, their London was very different to the one Gabriel and his queer comrades knew. For Hervey and Fox, one of their main objectives was setting up home together, despite the conventions of the day. However, because men like them were the very types who helped shape Britain’s laws and social customs, we will see how their elite status granted them the requisite privileges by which they might circumvent traditional domestic regulation. This, however, did not necessarily protect them from the attentions of their political enemies, who wished to expose their intimacies and bring them down.

Chapter Five introduces readers to John Chute and Francis Whithed, better known to their extensive coterie of effeminate bachelor friends as The Chuteheds. Once squirrelled comfortably away behind the red-brick façade of Chute’s impressive country pile, The Vyne, it quickly becomes apparent that ideas of a ‘queer community’ are archivally discernible at least as far back as the eighteenth century. Within these communities, as this group of devoted (and sometimes gloriously bitchy) friends demonstrates, a clearer sense of queer identity emerged. Unfortunately, as we shall discover, the queerer elements of these gender non-conforming

identities inspired a targeted proto-homophobic violence that will feel all too familiar to some readers today.

On the surface of it, Chapter Six is a rollicking Georgian adventure story that stretches the length and breadth of Europe. When examined more closely, though, it serves as a timely reminder of the importance of observing several coexisting and sometimes tension-filled subtleties when we talk about gender and sexuality, especially when those experiences are grounded in the past. As an influential courtier and spy, the Chevalier d’Éon experienced the might of royal power in both Britain and France. Yet he was also forced to drag himself through various dilapidated hovels before ending his days in penury. This remarkable gender-bending history has, in recent years, marked her out as a brilliantly defiant trans ancestor. However, to my surprise, I discovered that the Chevalier’s archive does not support this twenty-first-century interpretation. What I uncovered instead is a new, complex and yet profoundly queer interpretation of a life that deserves greater clarity and nuance in its telling. From this reinterpretation a new history emerges that aims to acknowledge the historical legacy of a much-overlooked section of the modern LGBTQIA + community.

I count Lady Eleanor Butler and Miss Sarah Ponsonby as my direct ancestors. Not because we’re blood kin but because, like them, I am a queer person originally from County Kilkenny in Ireland. Sometimes, when I’m home and walking along the high street or the parade, I think of them both traipsing the same lanes and alleyways as me, albeit centuries apart. So, in preparation for the research that went on to inform Chapter Seven, I was utterly charmed to follow in their footsteps, making my way from the port in Waterford, across the Irish Sea, and eventually to an impressive cottage in the small Welsh town of Llangollen. Eleanor and Sarah became famous as the Ladies of Llangollen, attracting the

attention of other same-sex-attracted women, poets and royalty alike. It is a wonderful story, and their life in Wales is well documented; less so their desperate start. I have combed the archives at the National Library of Ireland to reconstruct, in detail, their Irish adventures. For it was in Kilkenny that the true drama played out, leading Eleanor and Sarah to defy their families and abscond together. You will not find a tranquil history of an all-female rural idyll here. Instead, you’ll encounter a vigorous, determined tale of joyous defiance full of runnings away, disguises, midnight flits, yapping dogs, racing carriages and a crafty maidservant who was ferocious with a candlestick when backed into a corner. Very much my kind of history.

Chapter Eight charts a series of ‘sodomitical’ scandals that unfolded between William Beckford, ‘England’s wealthiest son’, and William ‘Kitty’ Courtenay, the 9th Earl of Devon. Initially both men were discovered together in a compromising situation in what has become known as the infamous ‘Powderham Scandal’. However, in light of new evidence, I propose that there was no such thing as the Powderham Scandal at all. This chapter also charts the various ways in which archives are tampered with in an attempt to deliberately erase the queer past.

I toyed with the idea of leaving Anne Lister out of this book. ‘What more is there to say?’ I thought. She has secured her place in queer history (and legend). She has achieved icon status and has even had her own TV show, for goodness’ sake! But when her history intersected with that of Lady Eleanor and Sarah in Llangollen, I found myself lost in the pages of her diaries once more, but this time from an altogether different perspective. Lister led a remarkable life, and we are forever indebted to her for the wealth of material with which she furnished the queer archive. But the more I read and re-read, the more it seemed clear to me that Lister was far from the ‘queero’ (queer hero) we invented following

Sally Wainwright’s Gentleman Jack (BBC /HBO ). Instead what I encountered was a female patriarch who was at times abusive and manipulative and often cruel. And so hurried emails were dashed off to Alex, my editor, admitting that although I’d initially wanted to exclude her, the project felt incomplete without her. Thankfully, he agreed. Her inclusion serves as a reminder that queer people in the past might have been brilliant, accomplished and noteworthy but also altogether flawed. Naturally, we feel less comfortable addressing some of these trickier examples, but it is unfair to expect those who came before us to embody modern ideals. Anne Lister was extraordinarily bold in her same-sex desire but she was also a product of her time, and that, as we shall discover, often led to some downright brutal actions.

The working-class labourer George Wilson assumes the penultimate position in Chapter Ten. Through him we uncover largely forgotten details about the lives of people who transed their gender identities. I also address the idea of queer emigration in the early nineteenth century, the first time (as far as I am aware) that the topic has been considered this far back. By comparing the cases of Kitty Courtenay and George Wilson we begin to uncover the hint of a pattern in queer travel, from Europe towards America – New York, to be precise. There, on the streets of the Lower East Side, Wilson embraced the traditional elements of immigrant workingclass life. That is until he was discovered by a policeman, three sheets to the wind, on a street corner in a well-to-do neighbourhood. What happened next confused and confounded authorities before Wilson silently slipped back into obscurity, where he felt most comfortable. Sometimes, for the people who lived them, their histories served them best when they remained hidden.

Finally, in Chapter Eleven, we meet the person who has stayed with me long after I’d left the letters, paintings and newspaper articles, the sketches and stately homes behind: Mary Jones, also

known as Peter Sewally. Jones’s history guides us down the less salubrious alleyways of New York City, not far from Wilson’s neighbourhood. It was there, alongside other sex workers, that she doggedly carved out a place for herself– no mean feat for a Black working-class sex worker who frequently transed her gender identity. Public reaction to Mary ranged from admiration and acceptance to fear and repulsion. She was even called a ‘monster’ by contemporaries because she dared to follow her own path, messy and winding as it might have been. There is a misconception still, I think, that to ‘make history’ one needs to disrupt or reshape it in some global way. But Mary Jones puts to rest this misconception and demonstrates that sometimes just getting back up when you’re so often told to stay down is all it takes to change the world.

What follows is a contested history. A history that is too dangerous, in some quarters, to take up space on library shelves or to be used as a point of historical reference in the classroom. It is the culmination of over five years spent teasing apart details discovered in various repositories across Britain, Ireland, Europe more generally and the United States. I make no apologies for what I found there. Rest assured, however, that I have interrogated my source material in the most robust manner possible throughout, as any historian would. As a result, not every case study I investigated met the burden of proof I set for inclusion. The history of the supposedly queer American Army general and Founding Father Friedrich Wilhelm August Heinrich Ferdinand von Steuben provides a cautionary example.

Numerous secondary sources, for example, will tell you that von Steuben was ‘openly gay’.8 In a 2023 graphic novel, Washington’s Gay General: The Legends and Loves of Baron von Steuben, Josh Trujillo and Levi Hastings state that their work is a biography of,

amongst other things, ‘a flamboyant homosexual . . in an era when the term didn’t even exist’.9 They dedicate their book ‘to the countless historians, queers, and allies throughout history who selflessly work to document, preserve, and share our incomplete story’. I second that dedication and acknowledge the incomplete nature of the historiographical work. But, after careful analysis, I have found no conclusive evidence that von Steuben helps us to complete it.

In support of the ‘von Steuben was gay’ theory, the journalist Erin Blakemore has argued that a party thrown by von Steuben shortly after he arrived at Valley Forge, to which none should be admitted that had on a ‘whole pair of breeches’, was sexually charged. Senator William North’s admission that ‘We love him [von Steuben] . . . and he deserves it for he loves us tenderly’ has also been put forward as proof of an unconventional three-way relationship between himself, Benjamin Walker and their former general. Others claim that von Steuben lived with North and Walker after the American Revolutionary War had ended. To help tally with the supposed queerness of this arrangement, all three men are seen to live under one roof (which they did not), and their wives are often missing from the narrative altogether. Whilst I fully appreciate the impetus to reclaim the queer past, these historical insinuations demonstrate a lack of the broader contextual knowledge required to interrogate the specific subtleties of same-sex desire, army life and friendship between men in the long eighteenth century. With this knowledge to hand, von Steuben’s apparent queerness quickly falls away.

For instance, at the point in the Revolutionary War when von Steuben’s trouserless army party was held, the Continental Army, historians agree, was without discipline, food, hope and, crucially, uniforms. Those lucky enough to have any clothing at all paraded in rags. Von Steuben’s request that soldiers attend his

party trouserless was not an opportunity for him to admire their shapely legs, merely a light-hearted acknowledgement of the terrible conditions he found them in. It was nothing more than an attempt to lift spirits before bringing the men in line and organizing them towards victory. With, may I add, decent uniforms.

Additionally, in the context of the late eighteenth century, men openly declared their love for one another, as North did in his letter, without the slightest implication of same-sex desire. Indeed, men linked arms in the street, even exchanged kisses without a hint of flirtation. Further, that von Steuben’s inner circle later wished to accommodate their former general and respected friend in their individual homes when he had fallen on hard times is not in the least bit unusual.

The truth is that such historical forays, however well intentioned, distract from our purpose. The von Steuben archive offers no concrete evidence whatsoever that von Steuben was what we would term queer. New evidence may well come to light which could convince me otherwise, and I’d caveat my conclusion by saying that this in no way means that he was not same-sexattracted. It simply means that I have seen no convincing archival material to support the claim that he was; this therefore excluded him from the purview of this book. I say this not to frustrate those who may once have advocated the importance of having identified a gay Founding Father, only to reassure sceptical readers that care and consideration have been applied to each of the following chapters.

As a direct result of its queerness, then, this book is an open invitation to discover a history previously obscured, a history that belongs to and has shaped all of us, even if we are not part of the queer community. For some of you, many of the histories that follow will feel instinctively personal. If that’s the case, I am glad

this book found you. I hope the adventures that follow make you punch the air in silent triumph, and mourn for what they (and we) have lost. I hope these accounts help to better root you in our once-hidden histories and direct you, more joyously and defiantly, towards a better future.

With that, let us begin.

CHAPTER ONE

A House on Field Lane

ONE S UNDAY NIGHT , F E b RUARY 1726. It had just passed nine o’clock as Gabriel Lawrence made his way purposefully towards Field Lane in Holborn. The winter darkness had transformed familiar London streets into something altogether more perilous, despite the intermittent grid of oil lamps. Flames, feeble and odorous, struggled to light the clogged arteries of the great city. Once night descended, even the savvy Londoner was forced to navigate an assault course of stinking waste (animal, vegetable and human), abandoned mounds of building rubble, and a rogue’s gallery of thieves, vagabonds and the desperate. Lawrence was keen to reach his destination.

As he walked apace, street musicians lifted their fiddles to offer a bawdy song, their bows slashing back and forth by their necks. The music they made underscored the continuous din from nearby alehouses, taverns and coffee houses; laughter, screams and shouts burst through doors left momentarily ajar – the strident, stinking symphony of the nocturnal city. Eighteenth-century London was never quiet. It remained a ‘prodigious and noisy’ place, ‘where repose and silence dare scarce shew their heads in the darkest night’.1

Forty-three-year-old Lawrence, jostling through the crowds, likely cast a distrustful eye towards the sky as he walked. The capital had temporarily emerged from a dramatic deluge that had soaked its people for some months. It had been bitterly cold too, unseasonably so, even for an English winter. Now that the rain had abated, Londoners squinted through a distorted haze of windows, wondering if they might soon be granted the welcome ease of spring.

Gabriel Lawrence was a milkman.2 For Lawrence, this meant early starts and heavy loads. Lawrence’s customers will have had some extra money in their purses as milk was less an everyday commodity in the eighteenth century than it is today; it was not a staple of the average Londoner’s diet. Gabriel Lawrence, therefore, will have spent his working days in middling and upper-class neighbourhoods where his product was more likely to sell. For now, though, the working day was behind him, and he sought comfort and camaraderie from an establishment run by Margaret Clap which was located on Field Lane.

Mark Partridge would be there, no doubt, for he was a regular in Clap’s exclusive coterie. He and Lawrence had recently had a messy spat which resulted in Lawrence losing his temper and, in the heat of the moment, calling Partridge a ‘vile Dog, a blowing up Bitch and other ill Names’.3 Lawrence had suspected Partridge of being loose-lipped about the closely guarded secrets of their hidden fraternity. Lawrence was concerned that Partridge, a sex worker whose knowledge was for sale in addition to his services, had divulged the sites of their meetings to those who were legally and morally opposed to them, those who wished to see them hang. Despite Lawrence’s suspicions, Partridge had somehow managed to reassure his friend that their secrets remained safe, and the two men had affectionately reconciled. So on that particular night it is safe to assume that Lawrence would have counted Partridge’s company as good as any other.

A

More tantalizing a prospect for Lawrence, the records show, was the possibility of his meeting again with one Martin Mackintosh, an orange-seller in Covent Garden. Amongst this particular group of friends Mackintosh went by the mouthwatering pseudonym ‘Orange Deb’. It was not unusual for these men to be given female nicknames or ‘maiden names’ that indicated something about their lives, personalities or professions and confirmed their place within this exclusive club. Martin/ Deb’s associates included ‘Dip-Candle Mary’, a candle-maker, the ‘Duchess of Camomile’, a resident of Camomile Street, ‘Old Fish Hannah’, a fish-seller, and ‘Susan Guzzle’, the origin of whose maiden name remains unclear (though I encourage you to use your imagination). When last they met, we know that Lawrence and Orange Deb, being ‘very fond [of] one another’, had ‘hugged and kissed and employed their Hands in [as some saw it] a very vile Manner’.4

As Lawrence turned right, with his back to the City, he finally found himself on Field Lane, ‘a narrow and dismal alley, leading to Saffron Hill’.5 In his Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster (1720) the clergyman, historian and biographer John Strype described Field Lane in rather uninviting terms; it was ‘narrow and mean, full of Butchers and Tripe Dressers, because the Ditch runs at the back of their Slaughter houses, and carries away the filth’. The locality was ‘of small account . . . and [was] pestered with small and ordinary alleys and courts taken up by the meaner sort of people; others are’, he observed, ‘nasty and inconsiderable’.6

However unpleasant, Field Lane was Gabriel Lawrence’s desired destination. As he pushed open the heavy wooden door to the premises, unseen observers silently confirmed that this man ‘belonged’ to the house: he was one of the regulars. Lawrence then slipped inside, allowing the door to close behind him. In that moment, unbeknownst to himself, he had sealed his fate.

Figure 1. Field Lane on John Rocque’s 1746 map of London: ‘A Plan of the Cities of London and Westminster, and Borough of Southwark’, John Pine & John Tinney, 1746.

We know that Margaret Clap was married to a man named John Clap. However, historians disagree as to the exact nature of their business. Some say they kept a ‘public’ house, others a coffee house, others a tavern, others still an alehouse of some sort. Some experts believe that the husband-and-wife entrepreneurs may have divided their labour; that John ran a tavern and Margaret a coffee house. Most likely, Clap’s was all of these things in various measures and, due to the diversity of their services, it was a relatively busy little spot. Contemporary accounts tell us that

Mrs Clap’s House was next to the Bunch of Grapes in Fieldlane, Holbourn . . . and for the better Conveniency of her

Customers, she had provided Beds in every Room in her House. She usually had 30 or 40 of such Persons there every Night, but more especially on a Sunday.7

Margaret Clap, rather than her husband John, has been largely credited with the successful running of their business. This falls in line with what we know about working-class women at this time as, contrary to popular opinion, they made a significant contribution to the eighteenth-century workforce. Many of the jobs these women undertook in the 1720s were associated with childcare, intimate care, housekeeping and the domestic sphere. This was hard and often undervalued work. Other women oversaw inns, lodging houses or coffee houses in an attempt to secure their financial future. Women often procured the licence for such businesses in their husband’s name.8 Margaret Clap had secured her house on Field Lane in this way and, like many of her contemporaries, she succeeded through a combination of necessity and economic aptitude.

Mrs Clap, discerning businesswoman that she was, had courted a loyal and distinct customer base. This included men like Gabriel Lawrence, Mark Partridge and Orange Deb. But if Mrs Clap’s clientele were loyal to her, they were no more loyal than she was to them. If any of her most frequent patrons, like a certain Mr Derwin, found themselves in a scrape with the authorities, then Mrs Clap was happy to bear witness, under oath, to their good character. Indeed, she had recently given evidence to a judge, Sir George Martins (a former Lord Mayor of London, no less), on behalf of the said Mr Derwin, who was accused, some gossiped, of committing sodomy with a linkboy.9 Mrs Clap later ‘boasted that what she had said before Sir George, in Derwin’s Favour, was a great Means of bringing him off [acquitting him]’.10 It was in this way that her customers came to refer to her as ‘Mother Clap’.

This practice of naming influential, non-kin elders ‘mother’ persists in the queer community today.11

Mother Clap’s belonged to a wider network of inns, taverns and coffee houses which formed a dynamic social patchwork across eighteenth-century London. At the upper end of the social scale, ‘principal’ inns provided not only an opportunity for men and women to eat, drink and chat together in a polite setting, they also acted as the location for some legal proceedings and public meetings. At the less salubrious end of the scale, Gabriel Lawrence would not have expected to meet members of the nobility or even the respectable middling classes at Mother Clap’s. Field Lane’s reputation tells us all we need to know about the general class of punter to be found there. It is sometimes said that eighteenthcentury inns and taverns were social melting pots, catering for those at the very top alongside the unfortunate creatures at the very bottom of society. In general, however, there is little support for this. Some establishments linked to theatres may have boasted a socially diverse customer profile, but most social spaces reinforced hierarchy; a social space for everybody, and everybody in their social space.

Once inside an establishment, regardless of its class strata, a customer became part of an ever-rotating, highly entertaining and politically engaged affair. The appeal of establishments like Mother Clap’s was manifold and included the opportunity to get away from home for a bit, friendship, a place of rest, a place to eat, warmth and an opportunity to learn and share news and gossip. It comes as no surprise, then, that coffee houses, taverns and inns grew in popularity at this time. Evidently, in no small part due to this popularity, the Claps seem to have managed to piece together a reasonable living for themselves on Field Lane. But despite its familial character and the relative success of their establishment, all was not well at Mother Clap’s.

We don’t know specifically what it was that alerted the authorities to her premises in the lead-up to February 1726. Her business, whilst popular, was likely unlicensed. In this, though, Clap’s would not have been unusual; many of the ‘lower sort’ of coffee houses, inns and taverns were. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, efforts were being made to regulate their activities, though unlicensed premises continued to flourish so it seems unlikely that this was the cause. More probable is that Mother Clap had come to the attention of local moralists and lawmakers because her patrons, without exception, were suspected sodomites. As witnesses at the time would come to testify, ‘Mrs Clap’s House was notorious for being a Molly-House.’

In 1709 the writer Ned Ward described the London fraternity of mollies thus:

THERE are a particular Gang of Sodomitical Wretches, in this Town, who call themselves the Mollies, and are so far degenerated from all masculine Deportment, or manly Exercises, that they rather fancy themselves Women, imitating all the little Vanities that custom has reconciled to the Female Sex, affecting to speak, Walk, Tattle, Curtsy, Cry, Scold, and to mimic all Manner of Effeminacy . . . 12

Contrary to Ward’s claims, most mollies did not fancy themselves as women, despite their gender non-conformity. What is irrefutably clear from Ward’s description, however, is that our queer eighteenth-century ancestors were recognized as part of a distinct social group that met together in ‘safe spaces’ like Margaret Clap’s.

To many in the eighteenth century like Ward, mollies were a disgrace to men and masculinity. Their marked femininity, noticeable in their gossiping, chatter and manner, set them apart from others of their sex. Ward condemned the effeminate manners of

the mollies, implying not only that they betrayed their own sex but that they mocked ‘the fairer sex’ in imitating them. Unlike the cotquean, who was a distinctly private, domestic and often rural type, the molly might be found in more public, urban spaces. To Ward and his ilk, mollies were a clear and present threat to traditional manhood and the family. But Ward went further and made it clear that mollies were not just effeminate men; they were specifically men who had sex with other men:

No sooner had they ended their Feast, and run through all the Ceremonies of their Theatrical way of Gossiping, but, having washed away, with Wine, all fear of Shame, as well as the Checks of Modesty, then they began to enter upon their Beastly Obscenities, and to take those infamous Liberties with one another, that no Man, who is not sunk into a State of Devilism, can think on without Blushing, or mention without a Christian Abhorrence of all such Heathenish Brutalities.13

By abandoning his ‘natural’ attraction to women, the molly threatened to topple the social order.

Mollies were not exclusively found at molly houses like Mother Clap’s, however. There were public sites where they ‘cruised’ for ‘trade’ too, particularly in Covent Garden, at London Bridge and along a path in Moorfields which became known as ‘The Sodomites’ Walk’. They also frequented the same social hotspots as everybody else. One disgruntled onlooker, having spotted ‘Pretty Fellows ’ at a popular coffee house in the West End, picked up his pen in disgust and wrote to The Tatler on 6 June 1709:

Some of them I have heard calling to one another as I have sat at White’s and St. James’s, by the Names of Betty, Nelly, and so forth. You see them accost each other with effeminate Airs: