INTRODUCTION

This book began over the kitchen sink a long time ago. I was doing the dishes after dinner. A CD of Radiohead’s album Kid A was playing, which got me thinking about a recently published book, e Rest Is Noise, by the classical music critic (and Radiohead fan) Alex Ross. Ross’s book told the story of modern classical music in light of the twentieth century’s political, social, and technological upheavals; it took a rarefied Western art form out of the shelter of the concert hall into streets and factories, cabarets and concentration camps. Connecting the music’s challenging, refractory character to the delirium of modern times, Ross established classical music as a shaping presence in the cultural life of the century, which continued to enliven the work of, for example, Radiohead. Radiohead’s lead singer had cut his artistic chops in a church choir, singing music that dated back to the Middle Ages—in the band’s keening, staticky, doom-laden anthems you could make out the hosannas—while the record Kid A was, I remember the not very well-founded rumor to have been, a nod to Theodor Adorno, the twentieth-century German philosopher who had been an unyielding champion of modern music at its most abrasive, as well as an unrelenting scourge of popular music. This was another of Ross’s achievements: to connect the music of the century past with the music of today.

Writing about art in a way that illuminates the art itself as well as the life of art in the world is tricky. Ross had pulled it off. Could the same thing be done with the novel? The situation of the novel was

different from the situation of so-called modern music. Far from slipping into notoriety and obscurity over the course of the last century, the novel had attained an even greater centrality to literary culture than it enjoyed in the past. It stood now as the literary form of the time, prestigious, popular, taken as both a mainstay of cultured conversation and of democratic culture. At the end of the twentieth century, the American pragmatist philosopher Richard Rorty went so far as to anoint it the touchstone of contemporary ethical awareness. Without a doubt, the novel was central to a certain contemporary sensibility: where, for example, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, educated English speakers would have turned to the ancients, to Shakespeare and the poets, and to the Bible for edification, in Rorty’s account they now picked up Lolita. I grew up between the pages of novels, and the better part of my adult life has been spent there too. Reading novels and thinking about the novel, the kinds of forms it has taken at different times and places and the ways they might continue to speak to readers today, has also been one of the pleasures and puzzles of my job as the editor of the New York Review Books Classics series. (I have never had the least interest in writing a novel—but that is another story.) It was the novel by which we had come to take the measure of who we were and who our neighbors were and what, for better or worse, we were all capable of: good, evil, deception, irony, truth. In America after 9/11, the recent publication of Jonathan Franzen’s e Corrections— a big novel about the latter days of the last century—came to seem a timely reassurance that a rattled superpower could still see its reflection in the mirror.

How had the novel come to occupy this position? Could the story be told? Perhaps, but an obvious problem emerged. Novels are set apart by language in a way that music is not, while the very attention they lavish on local customs and mores, which can make them so telling to those in the know, can also render them entirely inscrutable to those who are not. We distinguish French literature from English and English from American, and only so much news slips across those borders. At the start of the twentieth century, Virginia Woolf wondered quite seriously how English readers could be expected to make head

or tail of the translations of Russian literature that were beginning to appear at the time—and were, she was quite aware, already radically reshaping ideas of what the novel could be—when, she pointed out, Americans could hardly be counted on to grasp what was really going on, what was really at stake, in an English book. Her puzzlement, now, may seem exaggerated and even quaint, but the reasons for it haven’t gone away. The academic study of literature remains linked to university language departments, while our sentimental attachment to the novel draws on a sense of shared community. The novel, no matter how sophisticated, remains homey. No book is more densely located in language and place than Ulysses.

It would be hard then, I thought, to tell anything but the most summary story about the novel in the twentieth century, irrespective of languages and literatures. Perhaps it was impossible. Yet just as I was abandoning the idea, I glimpsed the outlines of this book. My thoughts turned again to the Russian novel, and the way it had made such an extraordinary impression on the literature of the world almost entirely in translation. “In translation” was the key, opening the way into the story of the novel, which was, as I suddenly saw it, a story of translation in the largest sense, not only from language to language and place to place but more broadly as the translation of lived reality into written form, something the expansive and adaptable form of the novel had from the start been uniquely open to, which the last century had provided the perfect—what?—petri dish in which it could further develop. On one hand, the twentieth century had been a century of staggering transformation—world war, revolution, women voting, empires falling, cities sprawling, expanded life spans and lives cut short, mass media, genocide, the threat of nuclear extinction, civil and human rights, and so on—a century to boggle the mind, which demanded and stretched and beggared description. On the other hand we had the novel, emerging from the nineteenth century as a robust presence with a tenacious worldly curiosity and a certain complacent self-regard, a form that was both ready to shake things up and asking to be shook up. Hadn’t the two, as the phrase goes, been made for each other?

The story of an exploding form in an exploding world? I thought it might make an interesting book.

More than a decade later, and well into a new century, here it is. What kind of book is it? As is so often true, it’s easier to start by saying what it isn’t. It isn’t a book about all the different kinds of novels written in the last century, which would be impossible for me and, I imagine, anyone to write. It is not a narrower survey, reviewing how key moments and developments of the last century found representation in the fiction of the times. It’s not—or only incidentally—a book about authors, notable or neglected, and how over the course of their careers they responded to such developments. Nor is it a book about artistic movements. A term like modernism has the usefulness of any carrying case, but it is hopelessly overused by now: the endless academic arguments about whether it is a backpack or a steamer trunk, and what to fit in or leave behind, have come to seem like the interminable deliberations of someone determined never to get out the door.

So much for what the book doesn’t do. What it does is establish a rough-and-ready category, the twentieth-century novel—a category of novels that have made it a point to puzzle over what they, the century and the novel, were doing together and how, in effect, they were to get along (a category that, it should be clear from the get-go, is by no means coextensive with every book written in the course of the century). Given that, the book then looks closely at some thirty novels by thirty different novelists, written over the course of rather more than a hundred years, in a number of languages, from places across the world. By “looks closely” I mean simply that it looks at the kinds of things these books show us in relation to the kind of show they make. This is how any work of art demands that we look at it: form is always another form of content. When we look closely at the novel in the twentieth century, we see an art form of extraordinary amplitude put under unprecedented ongoing stress, and we see too that certain novels—the ones I look at here, particularly—respond to that stress by radically reshaping the novel as a literary form. These are books in which the novel seeks to prove itself “equal,” in the words of the poet

Charles Olson, “to the real itself”—the real being all those realities of the bedroom and the abattoir that the novel in the nineteenth century had tended to keep in the background but which, in the twentieth century, it would place front and center along with all the previously unimaginable, too often unspeakable news that the new century delivered time and again. There were these drastic realities to put into words, to attest to, and along with them—no less urgent, no less real— was, as the century went on, the ever-altering, ever more searching sense of the different shapes that novels could now take.

The book begins not at the stroke of midnight on January 1, 1900, but in 1864 with the publication of Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground, an unclassifiable work—neither novel nor novella, at once confession and caricature—that would come to seem ever more ahead of its time and would go on being written and rewritten time and time again in the century to come by writers as different as Jean Rhys, Vladimir Nabokov, and Philip Roth. In many ways, the 1860s laid down the fractured foundation of that century. The decade had been preceded by the imperial and colonial establishment of the British Raj in India, and it was immediately followed by the unification of Germany, which would become a fiercely determined new contender for European and world power. The 1860s also bring the Meiji Restoration, inaugurating the modernization of Japan; they see the end of serfdom in Russia and, in the United States, after the first mass industrial war, the end of slavery. They see the publication of Karl Marx’s Capital. And 1860, I realize as I write, precedes my own birth by precisely a hundred years. I suppose this may stand as an indication of the provisional and essentially personal character of any timeline.

Such is the prologue to what follows, a book in three parts, the first of which takes us from the last years of the nineteenth century through the end of World War I. Here we meet writers who turn sharply away from their nineteenth-century forebears, rejecting existing forms of the novel and pioneering new ones shaped by the expansion of education and literacy, the new authority of science, changing social and sexual mores, the flow of books and people to and from places that previously had been inaccessibly far apart. I look at e Island of Doctor Moreau, by H. G. Wells, and e Immoralist, by André

Gide, two writers who could not be more unalike, yet whose shared impatience with social convention and hunger for new experience and understanding turn them into pioneers of the twentieth-century novel. Wells invents a new kind of fiction that questions everything imaginable, first and foremost the state of the world, and it turns out to be immensely popular with everyone everywhere; Gide, disdaining popularity, recasts the novel in the most rarefied and personal of forms, a move that is no less subversive and is increasingly influential in its own right. At the turn of the century, Colette’s Claudine novels and Rudyard Kipling’s Kim are bold tales of brash youth taking on the world at large, a world that is being remade around them, while Kafka’s Amerika and Gertrude Stein’s “Melanctha” refashion the paragraph and the sentence into suggestive new instruments of discovery. In Machado de Assis’s Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas and Natsume Sōseki’s Kokoro, the European novel is consciously refashioned in light of non-European realities, and something like a world literature begins to take shape. These are all urgent, exploratory, impatient books, full of anticipation and worldly appetite, and between them they advance attitudes and a repertoire of novel gestures that will provide a model for novelists to come. What does come, largely unexpectedly, is the Great War, welcomed at first by many as the storm that will clear the nineteenth century’s stagnant air, soon turning into a fouryear deadlock of destruction. Part One ends with three novels— e Magic Mountain, In Search of Lost Time, and Ulysses—that still stand as towering monuments of the twentieth century but are also direct responses to that war, reports from the novel’s front line.

After the war, the new century is no longer, in Wells’s words, the unknown “shape of things to come,” whether longed for or dreaded. For the novelists of the twenties it has become a present reality, and what to make of it becomes their task. Proust and Joyce provide models, but their work can seem as solipsistic as it is suggestive. Virginia Woolf, for example, takes Ulysses as an exercise in navel-gazing, even as she can’t deny (or accept) its importance, and in Mrs. Dalloway she finds a way to step around that obstacle, arriving at a style of her own and offering a spirited vision of men and women in the postwar world. Also written

in the shadow of Joyce, Ernest Hemingway’s first book, In Our Time, like Mrs. Dalloway, is a study in individual style, its narrative as splintered as its characters’ lives, its sentences stress tested. Robert Musil’s e Man Without Qualities, first sketched at the start of the century, interminably underway by the 1920s, finally interrupted by the author’s death in 1942, is a book that is a bit of every thing: satire, essay, philosophical inquiry, love story, and spiritual handbook, an attack on the novel as it exists and an effort to remake the novel as a lifesaving device.

Italo Svevo’s Confessions of Zeno, Jean Rhys’s Good Morning, Midnight, and the great novels of D. H. Lawrence offer singular fictional points of view on the life chances of modern men and women. (The upended, provisional relations between the sexes is a theme in all these books.) A new world war, not at all unanticipated this time and even more devastating than the last, brings this period of astonishing invention to an end. In Hans Erich Nossack’s e End, an account of the firebombing of Hamburg, and the two volumes of Vasily Grossman’s monumental tale of the Battle of Stalingrad, the battle that turned the tide of war against the fascist Axis, the imaginative resources of fiction struggle both to engage with and fight clear of unbearable fact.

How does it all end up? At times I have thought of the twentiethcentury novel as a fictional character in its own right and of this book as an old-fashioned picaresque, full of scrapes and capers, scares and narrow escapes, till at some point sightings of our protagonist become infrequent. She has no more news for us. There is no more news of him. They’ve gone missing once and for all. Something like that does happen, but before it does—in the long period of comparative peace and prosperity that, always under the threat of nuclear destruction, opens up the world after the war—the twentieth-century novel continues on its merry way. Great, flashy, scenery-chewing novels mark the moment, books that are at the same time marked with unsettling undertones of retrospection, reflection, and regret. Books like Lolita, Alejo Carpentier’s e Lost Steps, Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, and George Perec’s Life A User’s Manual seek both to live up to and even outdo the spectacular precedent of the century’s early masterpieces while also trying

to reckon with the scandal of the century’s history. That history becomes the overt subject of Elsa Morante’s no less prodigious History, while more concentrated books like Anna Banti’s Artemisia, Chinua Achebe’s ings Fall Apart, and Marguerite Yourcenar’s Memoirs of Hadrian look beyond the brutal and startling emergencies of modern times to recognize haunting specters of ages past. V. S. Naipaul’s e Enigma of Arrival, written after the defeat and demoralization of the United States in the Vietnam War and a few years before the collapse of the USSR—the end of what the historian Eric Hobsbawm would designate the short twentieth century—examines the life of a nameless, uprooted mid-twentieth-century writer born of a South Asian family in the West Indies, resident in England, as if from an infinite remove. That life, spanning the whole of the ever more traveled and commercialized twentieth-century world, is presented as only one more episode in the endless coming and going of peoples and worlds, the traffic of oblivion, and the book arrives at its moment of truth before a funeral pyre.

Why these books? Well, I hope the roll call above gives some sense of why I think they are telling. They are books with common concerns and with some common literary reference points— e Arabian Nights, Flaubert, the Russians prominent among them—but they can hardly be said to constitute a company or a tradition. My own formulation, the twentieth-century novel, is perhaps best taken as a useful fiction for considering how fiction responded to a century of fact, and though the books gathered and juxtaposed here could be seen to constitute a constellation, it is the limit of constellations, I am all too aware, to exist only in the beholder’s eye. Some of these books are what passes for canonical, but that is not what interests me about them, any more than setting up some sort of counter-canon of outcast texts. I am interested not in what books prove, one way or another (and in the end it is surely nothing), but in their life on the ground and on the page, which is what I have tried to bring out. The selection is personal, too. I have written about books that move me, always keeping in mind Randall Jarrell’s affectionate jibe about a novel being a long story with something wrong with it. Literature makes its own demand on our attention, and the power of literature—to respond to

the times, to transform our perceptions and our lives, to be itself—is not only my subject but also something that all the books here struggle to engage and bring to light. Late in the writing of the book it came to me that I could be said to see the novel as prophetic in form. It embarrassed me a bit, since I certainly don’t want to suggest that fiction should trade in portent and rebuke, and the books assembled here are neither finger-pointing nor finger-wagging. What I do mean is that literature is meant to open eyes.

The book covers a fair amount of ground. It also leaves a great deal out. I think of all the other books and other authors I would have liked to include, among them Rabindranath Tagore, Willa Cather, Mikhail Sholokhov, John Dos Passos, Louis Aragon, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Andrei Platonov, Daniel O. Fagunwa, Naguib Mahfouz, Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, Janet Lewis, Qian Zhongshu, John Cowper Powys, Giorgio Bassani, Marguerite Duras, Ingeborg Bachmann, Julio Cortázar, Joseph Heller, and so on and so on, and perhaps above all Joseph Conrad, whose unparalleled tetralogy—Heart of Darkness, Nostromo, e Secret Agent, and Under Western Eyes—invented the twentieth-century political novel, in which politics is a disease from which no recovery can be hoped. (In acknowledgment of omissions, I’ve provided a roundup of further reading at the end of the book.) I think of all the other things there are to say and how the case I make is by necessity a limited instance of the story I seek to tell. The books I write about are, for example, all written in major European languages (Sōseki’s Kokoro is the one exception), and this is hardly representative of the novel’s spread throughout the world or even in Europe itself. This book isn’t and doesn’t pretend to be comprehensive even within its own terms, and I hope it retains something of the casual quality of the thought experiment with which it first began.

Finally, a word about the manner of presentation. Broadly conceived, this is an essay in literary history, a work of descriptive criticism as practiced by such working critics as Clement Greenberg, Randall Jarrell, Pauline Kael, Elizabeth Hardwick, and Greil Marcus, but also by scholars like Eric Auerbach, Sydney Freedberg, Tony Tanner (in his great Prefaces to Shakespeare), and T. J. Clark. I suppose the models who mean most to me are three subjects of this book,

Henry James, Virginia Woolf, and D. H. Lawrence, whose criticism is as alert and as astonishing as any of their writing. All these critics are also artful writers, and their criticism arrives at its insights by sticking close to the work at hand while also seeking (struggling) to find words of its own to describe the work and the feelings and thoughts it evokes and contends with. It is, I’m sure, by tracking a novel’s turns of event and turns of phrase, its varied voices and points of view, stepping up to it and away from it, keeping an eye on it, paging through it (since the experience of reading a book, and a novel perhaps most of all, is inseparable from its presence in hand) that one begins to discern how it goes about making sense and how it matters and might continue to matter. The critic’s sense of a book is always partial and provisional, but so long as it doesn’t set out to substitute an interpretation or explanation for the book itself—well, then it may provide a glimpse of both the book in action and the action of reading the book—that hoped-for moment of encounter.

STRANGER THAN FICTION

PROLOGUE: THE ELLIPSIS

FYODOR DOSTOEVSKY’S NOTES FROM UNDERGROUND

It is the beginning of 1864. Fyodor Dostoevsky is in Moscow writing the first twentieth-century novel.

He doesn’t know it, of course. (He never will.) What he knows is that he is in a fi x. The only way to get out of it is to finish the work at hand.

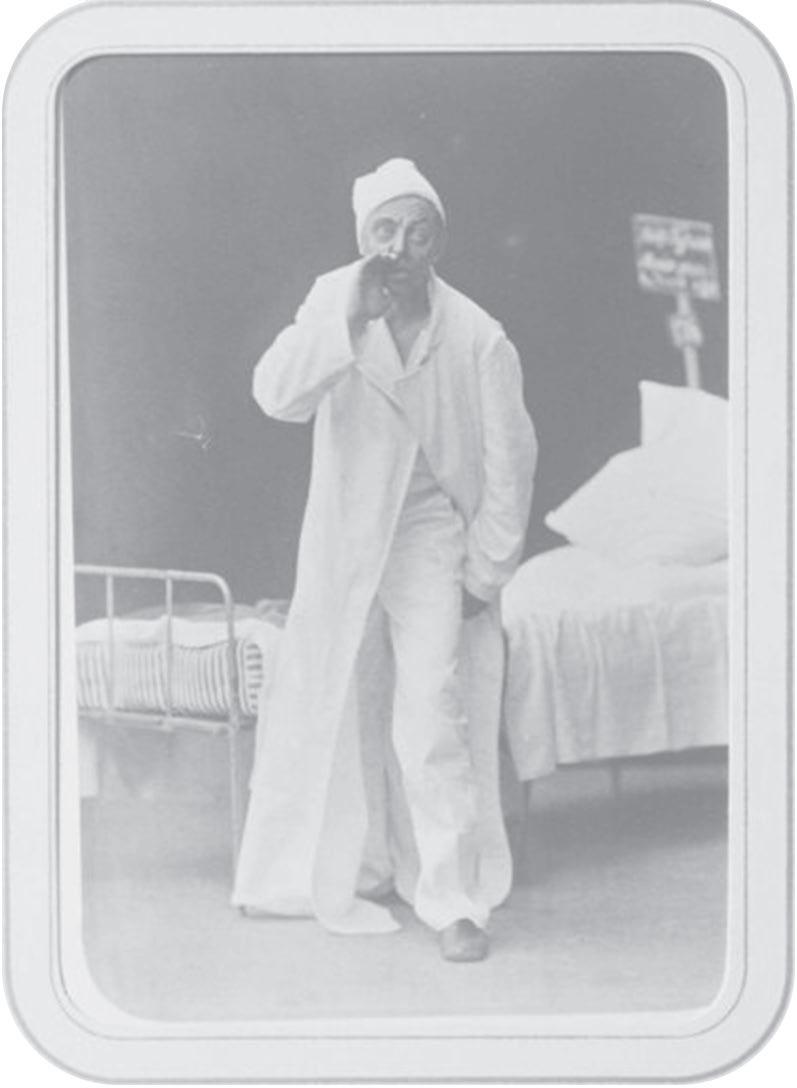

Dostoevsky was forty-two, unhappily married, childless. He was short, slight, high-strung, with pale, thin hair and a long, scraggly beard. He wrote manically, deep into the night, over endless cups of coffee, cigars, and cigarettes. He was always on deadline and always running behind. He suffered regularly from epileptic fits that left him debilitated for days.

He’d already made a name for himself as a novelist to watch and as an influential critic and editor. In 1861 he and his doggedly supportive older brother, Mikhail, had started a monthly magazine called Time, and it had developed a following. Tsar Alexander II had ascended the throne in 1855, and the early years of his reign were a time of openness to new ideas, leading, in 1861, to the emancipation of the serfs. Periodicals like Time, known as “thick magazines” as they could run to hundreds of pages, played an important role in nineteenth-century Russia’s intellectual and cultural life and had been especially influential during this period of transition.

Politically, the Dostoevsky brothers were proponents of what was

called pochvennichestvo, from the Russian word for soil, poch. Back to the soil. Dostoevsky felt that the way to reform Russian society— and few doubted that the tsar’s vast, unwieldy, politically regressive, economically underdeveloped empire needed some kind of reform— was to cultivate native Russian virtues and institutions, not to chase after Western fashions such as constitutionalism and capitalism. This belief aligned Dostoevsky with Slavophiles and conservatives, as well as with certain socialists, who were united in seeing modern, moneyed Europe as spiritually bankrupt. It set him completely apart, however, from the increasingly influential young radical utopian materialists—in many ways precursors to the Bolsheviks—sometimes characterized as nihilists.

The Dostoevsky brothers had positioned Time as a scourge of materialism and Europeanism that could serve as an honest broker in the dispute among patriotic “true” Russians, whether on the left or right, about where the country should go. It was a tricky balancing act, and in 1863 it came to a confused, almost comic end—disastrous for the brothers’ fortunes. That year in Warsaw there was an uprising of Polish nationalists against tsarist rule. Time had run a piece on the uprising, arguing that the Polish rebellion had an essentially European character. Given Time’s Slavophile sympathies, this was intended as a condemnation; the government censor—missing the right note of jingoistic outrage and mistaking subtlety for subterfuge—saw it instead as a seditious endorsement. Time was immediately shut down. In general, the government was turning away from the policy of reform, which had only prompted demands for further reform: the Poles were up in arms, the peasants restive. The closure of Time was part of a wider crackdown not just on dissent but on open discussion.

The previous year, the radical periodical e Contemporary had been shuttered for some months, then permitted to resume publication. Swamped by debt after the sudden demise of Time, Mikhail Dostoevsky hoped for a similar outcome. Instead, the authorities eventually gave him the go-ahead to begin an entirely new magazine. This was hardly a blessing. Time had an established reputation and a subscriber base that allowed it to turn a profit. All the work that had

gone into it would have to be done again. The new magazine—to be called Epoch—would have to be launched with a bang.

While this was going on, Fyodor had run off to Europe in pursuit of a young woman.

Apollonia (Polina) Suslova, who was in her twenties, had contributed a few articles to Time before becoming Dostoevsky’s mistress. At first she had been wildly in love with the middle-aged married writer. Soon, however, she was furious at his unwillingness to make their relationship public. He didn’t want to hurt his wife. Polina set off for Europe, and Dostoevsky pursued her to Italy. She led him on and put him off while he gambled away his own money and money borrowed from her or from Mikhail. When the affair came to its inevitable end and Dostoevsky returned to Russia, his wife, Maria Dmitrievna, was in the last throes of tuberculosis. “At every instant she sees death before her eyes,” Dostoevsky wrote to his brother. He began to suffer one violent epileptic attack after another.

Meanwhile, Epoch was demanding his attention. New fiction was needed for the first issue: he had commissioned a story by the celebrated Ivan Turgenev; then, largely for lack of anything by anyone else, he decided to contribute something of his own. Dostoevsky wasn’t sure just what form his contribution would take—a story, perhaps the start of a full-scale novel; one way or another, the work was “going badly.” “I have messed up something,” he wrote Mikhail, who had problems of his own: his young son died shortly after. Dostoevsky missed a February deadline, but then in March 1864 the work was done, sent to the censor, and approved for publication. When Dostoevsky received the printed magazine, he was shocked to discover that the censor had cut “the very idea of” his story. The thing has been left completely incomprehensible, he complained.

Desperation and uncertainty surrounded the composition and publication of Notes from Underground from the start. That uncertainty

would take on a life of its own in pages of frantic, baffled, scabrous, satiric, prophetic intensity. Uncertainty of the most matter-of-fact sort is evident in the note that preceded the first section of the work in Epoch:

Both the author of these notes and the “Notes” themselves are, it stands to reason, fictitious. And yet, individuals like the penner of such notes not only can, but even must exist in our society . . . In this excerpt the individual presents himself, his point of view, and, as it were, wishes to clarify the reasons for which he has appeared—and necessarily so—in our midst.

The reader can only wonder, What is this? What’s to come? Doesn’t the writer know?

Here the uncertainty is all the more striking for being compounded with inevitability. (What goes without saying, any savvy reader knows, is precisely what doesn’t.) The author sets himself apart from his character and then attributes to the character the same project—of proving that the character is a necessary manifestation of modern life—that the author claims as his own. How far apart, or close, are the two writers, fictional and actual, of these Notes, the very title of which is ambiguous? Notes—writing that is personal and provisional, anything but final—from Underground, a word with an unmistakable whiff of the grave, and, well, what could be more final than that?

The story begins, “I am a sick man . . .” It begins—and immediately breaks off with that ellipsis. Resumes: “I am an evil man. An unattractive man I am. I think my liver hurts.” And so it goes, an unfurling, furious scribble, filling the columns of Epoch.

Who is this? Not Dostoevsky, we’ve already been alerted (though he too was, as he wrote, a sick man), but some unknown yet representative character, some writer who is writing about himself and demanding our attention. Writing is a solitary activity, but this writer makes a pretense of being in our presence. “A moment, please! Allow me to catch

my breath . . .” The voice is nagging, needy, self-conscious, clowning, and hectoring. It is out of control, the voice of someone who accosts you on the street and won’t let you go.

The voice is a pain, and like pain it threatens to go on and never stop. But what claim does this pain have to implicate us in its existence? If we continue to read, isn’t that claim somehow borne out? So now there is a question in the air, or rather in our heads, into which, by a strange and distinctly disagreeable act of ventriloquism, the voice has slipped, occupying our thoughts: Why are you putting up with this? Who am I? Who are you? If you’re reading this, perhaps you’re sick too? Perhaps this is your pain?

Everything happens fast. The sentences are hard to focus on or follow. The subject keeps changing and yet somehow is always the same. The reader is ambushed, stunned.

Now the writer introduces himself, assumes a form: he is an educated man; a vain man, “guilty that I’m the most intelligent of all those who surround me”; a middle-aged man; a single man; “an intelligent person of the nineteenth century.” He is a forty-year-old former functionary from low down in the civil service who retired early to live on a meager inheritance in a seedy apartment in an outlying district of St. Petersburg, the “most abstract and calculated city on the whole earthly sphere.” He is, in other words, a nonentity: “I wanted to become an insect many times. But even that wasn’t afforded to me.”

And now, with swelling voice, he introduces a new character, us. “Ladies and Gentlemen,” he says, taking the spotlight. We, like him, are people of the nineteenth century, though unlike him in every other way. We are respectable, normal people, subscribing to wellfounded beliefs. “There’s no doubt in your mind,” he tells us. What do we believe? In progress, reason, science, in pursuing our own best interests, in maintaining and managing ourselves with the understanding and skill with which a trained mechanic operates a machine. We believe—or so the writer says—in the perfectibility of man and the inevitability of utopia, the crystal palace in which, with motives as

transparent as our deeds are good, we will all at last come to live in perfect harmony.

We believe that two times two equals four. And here the writer, Dostoevsky, introduces a memorable image:

For two times two as four is no longer life, ladies and gentlemen, but the beginning of death [ . . . ] Let us suppose that man does nothing but seek out this two times two as four, he swims across oceans, sacrifices his life in this seeking-out, but to seek it out, to truly fi nd it—oh Lordy, he’s somehow afraid of that. For he feels that, once he’s found it, then there’ll be nothing left to seek out [ . . . ] But two times two as four really is an unbearable thing. In my opinion, two times two as four is nothing but impudence—yessir. Two times two as four stands there with its hands at its sides, it’s in your way, it’s spitting in your direction. I agree that two times two as four is a superlative thing; but if we’re just going to heap praise on everything, then I say that two times two as five can also be a most sumptuous little thing sometimes.

By this time it has become impossible to say what kind of writing this is: confession, tract, polemic, rant, philosophy, literature, or, as the writer now tells us, anything but literature? And it seems to be about everything and nothing: the nineteenth century, politics, progress, literature, life. Well, it’s all lies, the writer now blurts out. These pages could never be published, after all; and even if someone were to offer to publish them, he would never allow it. What we are reading does not and could not exist.

And then Dostoevsky ends by playing the oldest, tawdriest trick in the book of writerly tricks: promising a story, one that will explain everything—next time.

Maria Dmitrievna died on April 16. Dostoevsky kept watch over her body that night, notebook in hand. It is an occasion for thought. “Masha is lying on the table. Will I meet Masha again?” And he continues:

“I” is the stumbling block . . . The highest use a man can make of his individuality . . . is to seemingly eliminate that I . . . And this indeed is the greatest happiness . . . Th is is the paradise of Christ . . . the fi nal goal of humanity . . . In my judgement it is completely senseless to attain such a great goal if upon attaining it everything is extinguished and disappears . . . Consequently, there is a future, heavenly life.

And much more in this vein, pages and pages of diary writing, with no further mention of Masha, though after a few entries we read “2 x 2 = 4 is fact, not science.”

A letter from some months later contains an epitaph for the marriage: “Despite being positively unhappy together (because of her strange, suspicious, and unhealthy fantastic character)—we could not cease loving each other; the unhappier we were, the more we became attached to each other. No matter how strange, that is how it was.”

Devastated, Dostoevsky continues to work on his book, the promised second part of which is due. He has only the sketchiest idea of where he is going. “I write and write . . . Mere verbiage, chatter, with an extremely bizarre tone, brutal and violent. It may displease.” At the same time, he insists to his brother, “It’s absolutely necessary that it be successful; it is necessary for me.”

Readers would have to wait until the July 1864 issue of Epoch to meet the writer of Notes from Underground again. The second part would seem to stand in a classically symmetrical relation to the first. If the first part ended with the claim that it was all lies, it also promised that the truth behind both parts, the cause of the effect, would be revealed in the second. Now, no longer protesting and disclaiming, the writer reappears as a more or less conventional first-person narrator, recounting a story from his youth.

The story may be conventional in form, but its content is shocking. Once upon a time, the narrator tells us, he was a devotee of the true, the good, the beautiful—and here’s what happened. Having gotten a minor job in the government bureaucracy, he decided to crash the farewell

dinner of a former classmate whose riches and popularity he envied. He makes a scene at the party, humiliating himself. His companions ditch him and head to a whorehouse; he follows and picks out a girl, Liza, fresh from the country and new to the job. They have sex, after which he earnestly warns her about the perils of her life and offers to help her mend her ways. Weeks later she shows up at his apartment. He is appalled. He mocks and vilifies her. Thinking back on the scene, he accuses himself: “Power, power was what I needed back then, games too, I needed to bring forth your tears, your humiliations, and your hysterics . . . How I hated her and how I was attracted to her in that moment! One feeling overpowered the other.” So he comes on to her. She is confused, then welcoming, loving; fifteen minutes later he wants her to leave. What he wants her to feel, in fact, is raped, though when she is at the door, he slips her some money before abruptly turning away. After which, crushed with guilt, he rushes out after her into the snowy night. But she is gone. Only the five-ruble note he tried to give her remains.

“Brutal and violent” this record of resentment, degradation, and violation is, and though not much of a story, it does seem like a page ripped out of real life. Ripped out of literature, too, ripped out and defaced, since this is nothing if not a send-up of those staple sentimental stories about earnest young men redeeming fallen women. The writer himself used to crave the fi x of that kind of fiction (“You speak somehow . . . as if you were reading a book,” Liza says to him questioningly), at least until his real, irredeemable character was exposed.

Not that he asks forgiveness: “I’m really not justifying myself . . .” In fact he thinks that what he’s done—and his willingness to tell us just what he’s done—ugly as it is, gives him a certain authority: “In my life, I have only taken to an extreme that which you didn’t even dare to take halfway, you took your own cowardice for prudence too, you used it to console yourselves, deceive yourselves. It is thus that I may still perhaps turn out ‘more alive’ than you.” Having presented himself as a nonentity in the first part, he now exposes himself as a monster. That is his peculiar authority, his proof of authenticity, but does it give him the right to address us as he does? To judge us?

At which point the book breaks off. Breaks off and resumes, ending (as it began) with a note from Dostoevsky: “In point of fact, the

‘notes’ of this paradoxalist do not end here. He could not restrain himself and continued on. But it also seems to us that we might as well stop here.”

He couldn’t resist and went on writing. This is fiction, we have been told, but not literature. The fictional narrator, in fact, has a horror of literature: “I’ve at least been ashamed the whole time I was writing this narration: as such, this is no kind of literature, but a corrective punishment.” He generalizes the point: “For we don’t even know where the living now lives—and what is it, what is it called? Leave us alone, without books, and we’ll immediately get all tangled up and lost.”

If literature is a problem throughout Notes, reality is even more so. Reality is associated with violent disruption. Why does the narrator decide to crash his classmate’s party, unwanted though he is? Because, “[If I don’t go], I’d then taunt myself for the rest of my life: ‘Alright then, you lost your nerve, reality made you lose your nerve and you lost your nerve.’ ” Going, he thinks, will result in “some radical rupture in my life,” though he adds sardonically, “It’s out of habit, perhaps, but for my whole life, at any external event, even the smallest of occurrences, it always seemed to me that some radical break in my life was impending, at that very moment.” And after his humiliation, what is his first thought? “So, there it is, there I’ve finally had my encounter with reality.”

Reality is associated with disruption, but also with compulsion: this is real writing, not literature, because it can’t be helped. Reality is also associated with pain, not to mention sickness. And though Notes may at times seem forbiddingly abstract, near hermetic in its hysteria, it is in fact very much connected to the real life of its own time. The book is almost topical.

The realities are global—those of a time and place that is ever more aware of what’s going on in the wider world, that is besieged by news and new ideas. The writer mentions the American Civil War and the Schleswig-Holstein confl ict, and of course the Crystal Palace, the celebrated centerpiece of the great 1851 World’s Fair in London in which Victorian England held up its power and prosperity for the admiration of the world. (Dostoevsky had visited the London fair of 1862

and left in horror.) Darwin comes up. On the Origin of Species had been published in 1859. The prospect of test-tube babies even makes an appearance.

The realities are also distinctly Russian. The writer identifies himself as a member of a particular Russian generation, the one that came of age in the 1840s—this is Dostoevsky’s own generation—and the second part of the book is set in the 1840s. The great inspiration to this generation was Vissarion Belinsky, an immensely influential literary and social critic—he started off as a high-minded romantic and ended up as a politically committed realist—and Dostoevsky’s first critical champion. This manic monologuist—Dostoevsky described his voice emerging as a continual scream—once stopped a guest from leaving his house in the early hours of the morning with the words “But we haven’t even gotten to God yet!”

The writer of Notes, who offers himself to a poor prostitute as her savior and then proceeds to rape her, is, among other things, a bitter caricature of the generation of the 1840s, with its sentimental and revolutionary dreams. And yet by identifying the writer as a resident of St. Petersburg, Dostoevsky places him in a different, more vertiginous, Russian historical perspective. Petersburg, built from scratch in a frozen Baltic swamp on the command and under the supervision of Peter the Great, is, like Versailles—or for that matter ancient Nineveh—both an assertion of absolute power and an expression of idealism. Petersburg, known as Russia’s “window on the west,” opened the prospect of a transformed empire, enlightened and prosperous, that would emerge in the future, and yet it remained inseparable from Russia’s despotic and murderous past.

Petersburg’s vast avenues, dwarfing statues, and looming government buildings are reflected in its shimmering canals or engulfed in freezing fog or by the wet snow that falls throughout the second part of Notes. The city had a hallucinatory aspect. At the center of Russian reality was a mirage.

Could literature help people penetrate the mirage? In Russia it had become the main forum for investigating the country’s unrealized

potential and sometimes deadly realities. Literature, you could say, was another kind of spying in a country full of spies, even as notable, good writers might find employment as government censors. Under the tutelage of reaction, Russian writers had learned how to play the stops of their language. Pushkin’s verse novel Eugene Onegin; the wild prose of Gogol’s Dead Souls (subtitled “an epic poem”); Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Time, a novel in the form of a bundle of stories; Turgenev’s Fathers and Children; Chernyshevsky’s fictional tract What Is to Be Done: these are bold, innovative books that sought out new forms—some found abroad, some very much homemade—to give imaginative currency to the life-and-death issues of the day.

Notes from Underground is certainly a conscious contribution to this ongoing, distinctively Russian exploration of Russian fact and fiction. Readers, familiar with Dostoevsky’s politics at the time, would have recognized it as a riposte to the revolutionary fantasies of What Is to Be Done? (published not long before Notes, and itself a response to Fathers and Children). In this enormously successful utopian novel, a cult book among the radical young, Nikolay Chernyshevsky, drawing inspiration from the 1851 Great Exhibition in London, envisioned an ideal future of material plenty and emotional harmony in the form of a crystal palace—the crystal palace that the Underground Man dismisses with disgust. Beyond that, however, the title of Dostoevsky’s work connects it to Gogol’s seminal Dead Souls and to Dostoevsky’s own autobiographical (as everyone knew, though it was disguised as fiction) Notes from the House of the Dead of 1859, then his most successful work to date.

Indeed, some readers coming to the new book, this new set of notes, this new confrontation with death, might well have expected a continuation of the earlier, autobiographical work, a reading that the note at the head of Notes might have been intended to head off. Head it off, or invite it, or at least conjure up the possibility. Because everyone knew that Dostoesvky, like his character, was a member of the generation of the 1840s, a legendary one in fact. They knew that for many years he too had been counted among the living dead.

The Dostoevsky of the 1840s had been a rising young writer. His first novel, Poor Folk, had come out in 1846 and was a great success. An epistolary novel about the hopeless love between a hapless copy clerk and the pretty girl next door, Poor Folk makes the human cost of poverty heartbreakingly vivid and was immediately hailed by Belinsky, who admired the way Dostoevsky made the reader feel for his rather pathetic characters and feel, too, that things like this shouldn’t be allowed to go on. Belinsky heaped praise on the young man, who did a brief star turn as Belinsky’s protégé and the next big thing. Before too long, however, Dostoevsky’s gaucherie, vanity, hypersensitivity—like the writer of Notes from Underground he was “extremely touchy . . . as suspicious and as quick to take offence as a hunchback or dwarf”— lost him most of the new friends he’d made.

He was in any case getting caught up in politics. Around the time Poor Folk made his name, Dostoevsky began to participate in a discussion group that met at the house of a radical young aristocrat, Mikhail Petrashevsky. In 1848, as nationalist and revolutionary uprisings challenged traditional dynastic powers throughout Europe, it was the Petrashevsky circle’s fervent hope that reform, even revolution, might at last come to Russia. Their enthusiasm was matched by Nicholas I’s alarm. The tsar even considered dispatching an army to defend Europe’s threatened rulers. At home, his spies set to work, and the meetings at Petrashevsky’s house were placed under surveillance.

The Petrashevsky circle was quite large, and over time it spawned various subgroups. Dostoevsky was a member of the so-called propaganda society, a covert groupuscule whose main mover was another radical young aristocrat, Nikolai Speshnev, a connoisseur of conspiracy who fascinated Dostoevsky. (“I am with him and belong to him,” he told a friend. “I have . . . my own Mephistopheles.”) The propaganda society had developed a plan to secretly assemble a printing press (access to printing presses was under government control) in order to publish seditious material: a pamphlet, for example, explaining in simple language that the tsar, in requiring peasants to serve in the army, was violating the commandment “Thou shalt not kill,” which meant that it was right to kill him. Tracts of this sort would prepare

the way for a popular uprising, and this, it was hoped, would find support from progressive elements in the army.

In April 1849 the authorities cracked down on the Petrashevsky circle. Dostoevsky was arrested in the middle of the night, along with some sixty other people. They were imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress, the tsarist Bastille. Many of the prisoners were released, but the ringleaders, including Dostoevsky, Speshnev, and Petrashevsky, were interrogated repeatedly throughout the summer as the authorities sought to link the radical talk of the circle to revolutionary conspiracy. They suspected the existence of something like the propaganda society but were never able to prove it. The prisoners were under enormous psychological pressure, but the conditions they lived in were comparatively benign. Dostoevsky had access to magazines and books—he read Jane Eyre—was free to correspond with his brothers, and even wrote a story. He wasn’t sure how his case would turn out, but he expected to be able to handle whatever happened.

On December 22, a bitterly cold day, Dostoevsky was awakened in darkness and driven in a carriage through crowded streets to the vast Semyonovsky Square. There he was reunited with his fellows from the Petrashevsky circle, all very excited to see one another. The men were led by an Orthodox priest to a raised platform and ordered to line up and remove their hats: they would learn what they had been found guilty of and the sentence that would be imposed. This was it: found guilty of conspiring against the government, they were condemned to go before the firing squad.

No one had expected it. It was impossible, Dostoevsky blurted out as he and his companions were ordered to strip and don the suits of cheap white sacking with white caps worn by men condemned to death. The priest called on them to repent. No one did. They were given a cross to kiss, and they kissed it. Three men, Petrashevsky among them, were escorted from the platfom to face the firing squad. Hoods were pulled down over their eyes—Petrashevsky, intransigent, pushed his back—and their arms were secured to stakes. The firing squad took aim. The other prisoners looked on from the platform, and there was a crowd in the square. Time passed, abruptly punctuated by

a roll of the drum. The soldiers lowered their guns. A messenger from the tsar had arrived: the death sentence had been commuted; the prisoners were to be sentenced to hard labor in Siberia instead.

The death sentence had in fact been entirely for show—but the prisoners didn’t know that. One of the men who had faced the firing squad went crazy for life. Dostoevsky, who had been next in line for execution, returned to his prison cell in a state of wild exultation. He wrote a letter to Mikhail:

Life is life everywhere . . . There will be people around me, and to be a man among men . . . that is what life is, that is its purpose . . . Yes, this is the truth! The head that created, that lived by the superior life of art, that recognized and became used to the highest spiritual values, that head has already been lopped off my shoulders. What is left is the memories and the images that I have already created but not yet given form to. They will lacerate and torment me now, it is true! But I have, inside me, the same heart, the same flesh and blood that can still love and suffer and pity and remember—and this, after all, is life. On voit le soleil!

“On voit le soleil” quotes from Victor Hugo’s novel e Last Day of a Condemned Man. No sooner is life restored than it turns to literature. There’s no mistaking that the voice we hear in this letter is the one we hear at the end of Notes from Underground.

Notes from the House of the Dead is Dostoevsky’s account of his years in prison camp. In Siberia, the convicts wear heavy fetters around their ankles (they are not designed to prevent escape; they are designed to infl ict pain) and different uniforms to match their crimes. A sullen silence reigns. Everybody has a story to tell, but it is a mistake to tell it and even worse to pry. They talk in their sleep, though. “We are beaten folks,” they explain. “The insides have been beaten out of us, that is why we call out of nights.”

The camp is under the direction of a drunken, sadistic major who

patrols the barracks at night, prods the prisoners awake, commands them to roll over. One day his pet poodle dies; he weeps inconsolably.

As a so-called “political,” above all as a gentleman, Dostoevsky is despised by his fellow convicts. They “wouldn’t mind murdering [you],” he’s told, “and no wonder. You’re a different sort of people, not like them.” He can’t write letters and is not allowed to receive them. (He doesn’t know this. He believes that his family has given up on him.) He is allowed to read the Bible. The convicts’ backbreaking labor is too much for him, and a sympathetic doctor gives him a pass to the infirmary. The patients wear gowns crusty with every kind of bodily discharge, including the blood of prisoners brought there, insensible with pain, to be patched up after running the gauntlet. What is the pain like? Dostoevsky wants to know. He cannot get a satisfactory description.

The prison camp depicted in Notes from the House of the Dead is a world where the inner life has been systematically destroyed. Spirit manifests itself only in explosions of destructive, and ultimately self-destructive, behavior. Dostoevsky looks at one prisoner—a particularly evil man—and sees only “a lump of flesh, with teeth and a stomach.” We sense that he has come to see himself this way, too.

What does it mean to be human? In prison Dostoevsky learns that to be human is to be capable of doing anything, of getting used to anything. For every different personality, he remarks, there is a different crime. This is finally a point of human pride, he thinks. The infinity of human perversion proves the freedom of the human soul.

To describe the “inexhaustible stream of the strangest surprises, the greatest enormities” that Dostoevsky confronted in Siberia—that, you could say, he had already confronted when he stared at death in Semyonovsky Square—he had to invent a new kind of writing. Founded on fact, e House of the Dead is a strange hybrid, as much an ethnography and an allegory of Russian life as it is an autobiographical novel. Much of the book is devoted to describing his first days in the camp. (Days after that, we understand, are all the same. They become years—four years in full—and then the years fall away.) The book is the record of an initiation; it is an initiation, at least insofar as reading

can assume the dimensions of reality, and that is the question Dostoevsky’s new writing proposes. The tone is largely deadpan. The book is submitted as evidence, not as an explanation.

Tolstoy and Turgenev thought e House of the Dead was Dostoevsky’s greatest work. It would have many successors in the twentieth century, from the terrible chronicles of the gassed trenches that would come out of World War I to the memoirs of the survivors of the world’s prisons and death camps. Literature or Life is the question posed by the title of Jorge Semprún’s memoir of Buchenwald. The title of Primo Levi’s great book about his time in Auschwitz raises another question, If is Is a Man. One of Dostoevsky’s convicts protests: “After all, I too am a man.” And then he pauses: “What do you think, am I man or aren’t I?”

And that too could just as well be the writer of Notes from Underground speaking. It has the sound of his bitter, self-wounding self-assertion.

Notes from the House of the Dead and Notes from Underground are related by more than their titles. They are related in conception, offering distinct but complementary takes on the same dilemmas of life and literature. In the earlier book we observe the prisoners’ lives from the outside. They are without freedom, and they have no way out. In the latter we are drawn into a certain tormented state of mind, no less imprisoning than the prison camp of e House of the Dead. In Notes from Underground the writing explodes and implodes, and all the time the writer is trapped inside it, not only unable to get out, but unable to see what it is he has gotten himself into, an inside that is all inside out, just as his squalid living space, his hole, the hole he is in, is indistinguishable from the space of his self.

This collapsing of inner and outer space becomes explicit, part of Dostoevsky’s artistic design, in the second part of the novel. The writer relaxes a bit, paints a comic, almost forgiving picture of his youthful self needing, after days of solitude, “to embrace all mankind immediately.” Here we step back into the social world, into which the main

characters of most nineteenth-century novels venture in order to meet the future and find their proper place, be it good or bad. And yet, having briefly raised the expectation of a story with a normal development and conclusion—a story of the day, like Turgenev’s elegant Fathers and Children—Dostoevsky decisively frustrates it. Notes from Underground takes us back into the past and dumps us there like a dead body.

For the reader, in other words, there is no more possibility of escape than there is for the writer. Even more than House of the Dead, Notes exists to make us confront an intractable reality, one that demands our attention but does not respond to it. The book doesn’t describe this reality so much as impose it upon us.

In this way, Notes introduces a conception of reality, and a relation of author and reader to it, that are quite different from reality as it had been previously represented in what, conventionally, we refer to as the nineteenth-century realist novel. How is it different? After all, Dostoevsky, whose first literary undertaking was a translation of Balzac’s Eugénie Grandet, is as deeply engaged with the still-thriving tradition of the nineteenth-century novel as his near contemporary Flaubert is or as Henry James will be. And yet Notes from Underground represents as significant a shift in the history of the novel as does Karl Marx’s adage “the philosophers have only interpreted the world; the point is to change it” in the history of philosophy.

Reviewing a novel that is roughly contemporary with Dostoevsky’s Notes, Anthony Trollope’s Can You Forgive Her? of 1865, the young Henry James witheringly begins, “This new novel of Mr. Trollope’s has nothing new to teach us either about Mr. Trollope himself as a novelist, about English society as a theme for the novelist, or, failing information on these points, about the complex human heart.” James’s sally captures the conventional view of the day of what the novel should do quite exactly, and the criticism would have been all the more wounding since Trollope certainly shared its assumptions. That view, as described in Ian Watt’s classic study e Rise of the Novel, had gradually taken shape, especially in England, over the course of the

eighteenth century. Samuel Richardson’s novels, the tragic Clarissa (1748) above all, had introduced a new emotional realism to the genre. Their epistolary form allowed the novelist to put his pen in the hand of his characters, who are set free to track the motions of their minds and hearts, in which the reader may become as absorbed as they are. (Clarissa was in a sense the first cult novel; the cult was international and huge.) The comic fiction of Henry Fielding, by contrast, demonstrates what Watt calls a realism of assessment, as Fielding sizes up his characters’ deeds and motivations with a shrewd, worldly eye, the better to entertain but also to educate the reader in the ways of the world. Toward the end of the century, these two forms of realism come together, Watt argues, in Sterne’s Tristram Shandy (a triumph of rococo whimsy, as authorially playful as its characters are silly and moody, that was another international hit) and, especially, in the work of Jane Austen. In the very title of Sense and Sensibility, the perils and possibilities of two distinct ways of perceiving and responding to the world are presented for our consideration (and amusement): one (sense) alert to the world at large and to the consequences of our actions; the other (sensibility), which attends to the world of feelings. There are, in other words, claims that the world, or society, makes on us and claims made by the self, and within the capacious and welcoming confines of the great nineteenth-century novels that follow from Austen, claims of both sorts must find accommodation. Indeed—it is implicitly suggested—it is simple common sense to recognize that only by integrating these two views can a proper—realistic—relation to reality as a whole will emerge, whereas clinging exclusively to one or the other way of seeing things will lead to disappointing, if not tragic, results. Yet the seemingly simple imperative of responding to the summons of common sense turns out to be much harder than anyone would imagine, or so the nineteenth-century novel works to show. The problem is of infinite interest, in fact—and significant risk. If Emma Woodhouse finds her Mr. Knightley, Emma Bovary finds death.

Description or imitation is of course central to the power of the nineteenth-century novel, but its vaunted realism doesn’t stem from its many realistic effects, persuasive and pleasurable though they are,

so much as it does from the judgment it displays in assembling such features of the common human predicament for our consideration. Character and situation, expressed and explored through a reliable interplay of dialogue and description conducted under narrative oversight: that’s the form the novel settled into in the nineteenth century, and which the vast majority of novels take to this day.

Dialogue and description are of essence to the nineteenth-century novel, especially as it develops in the metropolitan centers of London and Paris. So too of course are plot and story. People often say that a novel needs to tell a good story, but in fact the stories told by novels are for the most part commonplace (and unremarkable and unmemorable compared with the wondrous or thigh-slapping stories of, say, e Decameron or e Arabian Nights). There is nothing unusual or unlikely about the stories of either Emma Woodhouse or Emma Bovary, and it’s just that ordinariness that recommends them to our attention. These are not books of marvels, but books about things we know something about.

Ordinary though it may be, the story must still be made to enthrall, and to this end the nineteenth-century novel resorts to plotting, the elaboration, that is, of how the story unfolds until it is fully told. Plot is distinct from story—the Russian formalist critic Yuri Tynianov drew a sharp analytic distinction between them in the 1920s, and E. M. Forster, in his Aspects of the Novel, also emphasizes their difference— and plot, even more than the interaction of dialogue and description, works in complicated ways. Plot paces the story, its convolutions both revealing and obscuring it; it tantalizes and leads readers on until they yield themselves to the author, unable to “put the book down.” Plot has a seductive dimension, in other words, and this side of it is just what makes Marianne Dashwood’s sensibility, in Austen’s novel, thrill to novels. Plot, however, is equally a sign that the book as a whole is under authorial and perhaps even providential control: the continuities will be maintained, and everything will at last come round, at least if the novel is any good. And plot finally engages the reader as the judge of whether in fact it is any good. The plot of a nineteenth-century novel is in a way analogous to the developing representative politics of the nineteenth century, or for that matter to a well-run railway sys-

tem. The novelist must find a place in his pages for all his characters, with all their various motives, and keep things under control (even as they threaten to break apart). And all the time, the novelist is also working to obtain the reader’s vote of confidence.

None of these things are on offer in Notes from Underground, where there is no plot, just a travesty of one, and hardly any story to speak of. To the contrary, as the writer might squawkingly interject. Emerging from a state of comprehensive crisis—personal, professional, financial, political, national, philosophical, religious, and certainly literary— Notes resembles nothing so much as a swept-up heap of broken glass. The book gives voice to views that Dostoevsky shares (for example, the essential and necessary perversity of the human will) but also to ones that he does not (the writer mocks the back-to-the-soil program Dostoevsky had espoused). It is a send-up of conventional romantic literary themes (the redemption of the fallen woman) that flirts with a certain Christian sentimentality of its own. (Perhaps what would redeem the writer is love?) It is a psychological study and a caricature of a generational type. It is an attack on the bien-pensant bourgeoisie, an attack on utopian radicals, an attack on idealism, an attack on literature, an attack on Russia, an attack on “our unfortunate nineteenth century.” (“Just take a look around: blood flows in rivers and in such gleeful fashion, like champagne. That’s the whole of the nineteenth century for you.”) It is a howl of dismay, a mere personal gripe, and an expression of defeat. It is an essay in paradox: this hopeless man gives voice to unmistakable truths; this man who gives voice to unmistakable truths knows nothing, is hopeless. Formally not much of a story, it retains something of story while also being a polemic, a satire, a philosophical meditation, a case study.

The thing is, it is all these things (and more) but none of them definitively or conclusively. “This is a form, nothing but an empty form [ . . . ] I don’t want to be restricted in any way [ . . . ] Whatever occurs to me I shall put down . . .” the writer says, and what he writes does not make sense of his crisis (which is somehow everybody’s crisis) so much as enact it helter-skelter. Embodiment is what he is after, in “real flesh and blood” (and it is hardly coincidental that slaughter holds

such a grip on his imagination). The writer may be despicable, combining all the attributes, as he says, of an antihero, yet his voice retains an impersonal power and an authority of its own. And whose voice finally is it anyway? The voice is supremely equivocal: Dostoevsky’s or not; ours (as we are repeatedly told) or not (as we are also told); public address or interior monologue; the voice, variously, of the 1840s, of the 1860s, of Russia, of “our unhappy nineteenth century.” Supremely equivocal and not just unreliable, radically unreliable. But real.

This is the voice of the twentieth-century novel.

Notes stands as a precursor in part because the kind of political and social problems that Russia faced in the nineteenth century, which seemed at that point distinctively Russian, become general, indeed global, in the century to come. Like the writer of Notes, like Dostoevsky on Semyonovsky Square, the writers of the twentieth century are ambushed by history. They exist in a world where the dynamic balance between self and society that the nineteenth-century novel sought to maintain can no longer be maintained, even as a fiction.

Influential twentieth-century novelists, from Proust and Mann to David Foster Wallace, have written about the importance of Dostoevsky to their work, and Notes in particular echoes with uncanny frequency through the novels of the twentieth century. (So much so that I suspect that many of the echoes are in fact indirect: an echo of an echo.) Consider, in any case: the book introduces an archetype; the anonymous writer of Notes becomes the Underground Man, as much a modern myth, Dostoevsky’s American biographer Joseph Frank has rightly said, as Faust, Hamlet, Don Juan, or Sherlock Holmes. The shadow of this mythic character can be detected in the protagonist of Knut Hamsun’s Hunger, Jean Rhys’s lost women, Gombrowicz’s Ferdydurke, Bellow’s Dangling Man, Ellison’s Invisible Man, and Bernhard’s e Loser, among many others. The book introduces a setting: call it the infinitesimal, infinitely squalid retreat in the midst of the inconceivably spreading urban wasteland. In Kafk a’s novels and stories this setting becomes the world. Flann O’Brien relocates it to