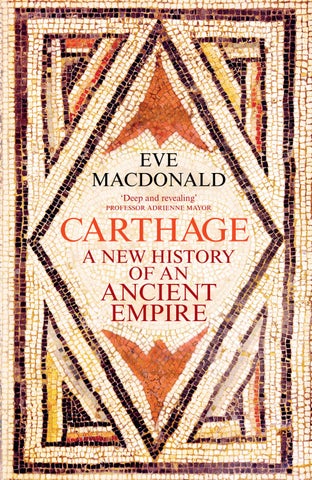

‘Deep and revealing’ PROFESSOR ADRIENNE

‘Deep and revealing’ PROFESSOR ADRIENNE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Ebury Press is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW

penguin.co.uk global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published by Ebury Press in 2025 1

Copyright © Eve MacDonald 2025 Maps © Helen Stirling

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset in 11.7/16 pt Calluna by Six Red Marbles UK , Thetford, Norfolk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Hardback ISBN 9781529911671

Trade Paperback ISBN 9781529911688

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

The city is aflame, burning in a Roman blaze after three long years of siege. The last holdouts take refuge in the great citadel known as the Byrsa hill. Among these desperate few is the wife of the commander of Carthage. Her name is not recorded but we know her husband was Hasdrubal, and she had their two children with her. Dressed in her finest clothes, she stands on the ramparts gazing down on the carnage below. She sees her beautiful city in flames, and images of unimaginable chaos, death and suffering. She is witnessing the final scene of Carthage, the very last moments of the city, in the year 146 B c E . For six days and nights Roman soldiers have fought and slaughtered their way from the ports, across the marketplace, to the top of the hill, street by street, facing resistance from the Carthaginian population. So fierce has the resistance been that the Romans had to send in sweepers, whose only job was to push the dead out of the way as more and more reinforcements piled in. The heavily armed infantry, the famed legionaries of the Roman army, have been unrelenting in their destruction. At this moment, the wife of Hasdrubal, looking down from the citadel, spots the Roman commander, Scipio Aemilianus, adopted grandson of the famous Scipio Africanus, conqueror of Hannibal. She looks closer and sees that her husband Hasdrubal has surrendered to him and now kneels at Scipio’s feet.

The wife of Hasdrubal addresses Scipio directly from the ramparts and, as quoted by a later historian named Appian, says, ‘For you, Roman, the gods have no cause of indignation, since

you exercise the right of war.’ With these words, she absolves her enemies and their destruction of her city. She continues to call down to the Roman commander but trains her eyes on her husband, who gets no such absolution: ‘Upon this Hasdrubal, betrayer of his country and her temples, of me and his children, may the gods of Carthage take vengeance and you be their instrument.’ For Hasdrubal’s betrayal is both public, in his role as chief magistrate and defender of Carthage, and personal, as her husband who has failed in his duties. Hasdrubal has forsaken his oaths to the city and her gods, and has left his wife and children to fend for themselves. She calls him a wretch and a traitor and taunts him with his future of ‘decorating a Roman triumph’, being paraded through the streets of Rome as a trophy of war. And finally, she accuses him of being the ‘most effeminate of men’ and one who has left his family to be engulfed in flames. With these final words, the last ever spoken by a Carthaginian, she turns and kills her own terrified children, throwing them down into the fire. In her final act, she flings herself after them. The end of Carthage comes with this ultimate statement of death over enslavement, of suicide over capture.

What was Carthage and who were the Carthaginians? Why did the Romans destroy them so completely? From the first time I set foot on the place that once was ancient Carthage, near the modern city of Tunis in the country of Tunisia, I was fascinated by these questions. The beauty of the place captured me, along with the haunting memories that reside there and all the many faces of the city. For 600 years Carthage was a dominant player in the history of the ancient world and a foundational power of the western Mediterranean, but its importance was largely erased by the Romans over the centuries after their conquest. Here I have set out to explore the city and lives of its citizens across its

long and illustrious history, bringing their stories to the fore after two millennia in which their tales have been told by those who destroyed them. In doing so, we uncover a civilisation that was a fundamental part of the ancient Mediterranean, whose cultural presence is still felt across the whole of the North African coast, Portugal and Spain, mainland Italy, and the islands of Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica.

There are challenges in trying to address these questions of who the Carthaginians were, and even what Carthage was. Theirs is a fragmented history, distorted and rearranged, a puzzle with key pieces missing. The final lines of the dramatic scene set by Appian above captures the problem. Much that we know of the Carthaginians is filtered through a lens created for us by their enemies. So Hasdrubal’s wife condemns her husband for posterity, and with it, all Carthaginian men are condemned, for this idea of the effeminate man was a great insult in the Roman and Greek male mind. The Carthaginian Hasdrubal does not act like a man, and he is willing to suffer humiliation, even slavery, rather than protect his wife and children, his city and gods or to take his own life. Not so his brave spouse, whose final act, the hurling of herself and her children on to a funeral pyre – while possibly a scene entirely invented by the Romans – is admired by the Roman historian. Appian sums up the scene with the line, ‘in this way the wife of Hasdrubal died, an end that would have been more fitting to himself.’ Even this most famous of stories is told, in the traditional narratives, with a Roman slant.1 With this book, I aim to interrogate the Roman sources and draw on new archaeological evidence to allow a much more nuanced Carthage to take shape.

The dramatic story of Carthage and its rise and fall has fascinated people for millennia. The tales of Dido and Hannibal, of great wealth, total war and ultimate tragedy make for a

compelling narrative. Only now can we weave them into a story that includes new information and greater depths of understanding produced by the leaps in archaeological research over the past 20 years. New DNA and stable isotope analysis of human remains from mass graves at the site of Himera in Sicily give us insights into the far-flung origins of the people buried there. Archaeologists from Tunisia and the Netherlands have used radiocarbon dating on samples from deep excavations at Carthage that confirm the foundation of the city in the ninth century B c E . The ongoing studies, excavations and research from across the Mediterranean have begun to provide a foundation for the real story of Carthage that takes us beyond the Roman story and is underpinned by technological advancement, industrial innovations and multicultural populations. We can now tell of new perspectives on the city and its place in the wider world.

At its height in the third century B c E , Carthage was a technologically advanced culture and a city of possibly 250,000 people – although this number is likely inflated. It sat in a geographically perfect location on the north coast of Africa linked to points east and west across the Mediterranean Sea, and north and south reaching into the African continent (see page 10). Carthage was also founded in the midst of rich agricultural land and abundant natural resources, which the Carthaginians fully exploited. In fact, the only piece of Carthaginian literature that the Romans preserved from its libraries after their destruction of the city was the text of a man named Mago who wrote about agricultural techniques and innovation, how to cultivate the best wine and what species of plants thrived in the landscape. So advanced was the Carthaginian agricultural technology and land, so rich was Carthage as a place of connectivity, that it was in conquering Carthage that the Romans came to be the power that went on to rule the entire Mediterranean. Many would argue, including the

ancient Romans, that without Carthage, there would have been no Roman Empire.

The people of Carthage and the culture that existed there are often referred to as ‘Punic’, a word commonly used to refer to people who were part of a large Phoenician-speaking diaspora and whose cultural focus was the central and western Mediterranean. Punic Wars, Punic behaviours and all things Punic are described by the Roman sources. ‘Punic’ is a difficult word; its origins rest in a cultural stereotype that the Romans created about their old enemy. The word comes from the Latin word Poenus, which is believed to derive from the Phoenician origins of the Carthaginians. Being Punic was not a compliment in the third-century B c E Roman mind, but it is the name that has stuck and been used for the Carthaginians since. For a lack of anything better, I use the word ‘Punic’ here too, with some distinction between Carthaginian and west Phoenician identities especially in the earlier periods of their history.2

Many books have been written about Carthage and its history over the centuries, starting with lost ancient Roman epic poems such as Naevius’ Bellum Poenicum about the First Punic War and works of other writers whose stories are some of the earliest surviving examples of Latin literature, written in the third and second centuries B c E . So Rome’s wars with Carthage were the events that shaped early Latin literature, and became a fundamental part of the city’s memories and construction of an epic past.3 The second- century history by the Greek Polybius is an essential part of any narrative of Carthage and was hugely influential on later histories written in the early Roman Empire, such as Livy’s monumental work in Latin on the story of Rome, Ab urbe condita (‘From the Foundation of the City’). Also important were Latin imperial epics like Silius Italicus’ Punica and the later works by the Greek-language authors of Roman history like

Appian, who we saw above, and Plutarch. In the centuries that followed the destruction of Carthage, the Romans continued to be fascinated by the events of the wars and to tell these as formational tales. Many different sources, ranging from classical Greek writers like Herodotus and Thucydides to late Roman historians, will be used as we unfold Carthage’s story. The ancient views are essential, but we always must consider that Carthage was ultimately projected as ‘the other’ in almost all of these texts. This ‘othering’ of Carthage continued well into the post-antique period when the memory of Rome and its empire was mused upon by Arabic geographers, medieval scholars, Renaissance writers and early modern composers.4

Today we still find this perspective, especially in the ways that Carthage appears in the history of Rome, often only as its ultimate enemy. Here I have told the history of Carthage and its citizens through key individuals or places and the seminal events that shaped the civilisation’s history and destiny, always trying to keep a Carthaginian view at the fore, wherever possible. We begin with the Phoenicians and the foundation of Carthage as a colony of Tyre in Chapter 1. Here we meet the beautiful founder of the city, the queen Dido, and look at the myths and legends that survive of this deep past in the ninth century B c E . The early chapters look at the way that Carthage was drawn into the politics and power struggles of the eastern Mediterranean, where the Achaemenid Persian Empire and the archaic Greek cities struggled for dominance. We will examine how Carthage engaged with its neighbours and developed its own cultural and religious identity over the sixth and fifth centuries B c E and will explore Carthage as it begins to flex its muscles in the western Mediterranean within a multicultural and competitive world of Greeks, Phoenicians, Etruscans and Romans. Chapters 4 and 5 look at Carthaginian interactions with Greek cities on Sicily and

show how Carthage’s history was intricately linked to larger geopolitical shifts and the ideas created from the conquests of Alexander in the fourth century B c E . By the height of Carthaginian power in the third century B c E , individual actors and the politics of the ‘Hellenistic’ successor kingdoms became the model by which to see famous Carthaginian generals like Hannibal.

In the latter half of the book, we meet with Carthage as an empire and follow the continuum of rivalries and expansion of power through the third and into the second century B c E . Chapters 6 and 7 look at the conditions for a western Mediterranean-wide war and the battle for Sicily that became known as the First Punic War. The Second Punic War – arguably the most renowned episode in Carthaginian history – is covered in Chapters 8 to 10, and we follow Hannibal as he leads his elephants into Italy and challenges Rome to its very core. In Chapters 11 and 12 we look at the final 50 years of Carthage, as the battle with Rome leads to Carthage’s last gasp and its final annihilation. After Carthage’s destruction, in the final chapter we follow the vestiges of the Carthaginians that survived the destruction and the long memory of the city. We will see how the residues of Carthage can be found across the Roman Mediterranean and still exist right up to the present day.

Underlying so much of the story of Carthage is its identity as a North African city. On North African soil were its closest allies, its bitterest enemies, shared myths and local traditions. The indigenous people of North Africa, today’s Amazigh, were referred to as Numidian/Libyan or sometimes Berber in ancient and medieval texts, and they were an essential part of Carthage’s make-up and history. From the beginning to the end of Carthage’s history we will explore the stories of the African communities – as allies of Carthage, and in terms of the intermarriage and identities that created the distinct people that we call Carthaginians.

Here I either use the word ‘Numidian’ or ‘Libyan’ for the indigenous North Africans unless referring to a specific people by the name of their kingdom or city.

My ambition with this book is to tell a story of Carthage that is both an epic tale and an account that helps us to gain a better understanding of the real people who lived and thrived in this beautiful city on the sea in the centuries before Rome. The Romans didn’t want anyone – their people or their adversaries, their citizens or their descendants – to fully understand or see Carthage or its citizens as real people; they wanted the Carthaginians to forever be seen as the enemy. My aim, and the journey of this book, is to reveal, as much as is possible, what the Romans tried to make us forget: that Carthage has always been one of the foundational cultures of the ancient western Mediterranean. And if we look hard enough, we will see that without all that Carthage was, there would have been no Rome.

P an o rmus s

Sicil y

Sardinia

Carali s N or a Su l ci s i Cape Bon se Sy racu s si n a es s Me s

Cartha g e Utic a M ozia o a z Drep anu m L i l y b a mue Malta 0 0

Mediterranean

By bl o s A radu s Uga ri t

Kition on ion

Be i ru t B Jerusale m J Dor D Ga z a Ty r e Jo p pa Si d on S

R om e

Carthage and the Phoenician

Corsica

Sardinia

Pa n o rm us ( Palermo )

Sicily

Sy racuse

ge

Naucratis

Alexandria A M emphi s

Phoenician cities Phoenician settlements Other cities Phoenician trade ro utes Ar ea of Phoenician settlemen t D r a a iRrev metu m Ha d ru m t

Cy re ne n s ns en Athens

Nor a ra Th ar ro s cis i Sul c A la ri a Ma s sa l ia M C ae r e Pyrgi s Lixus Li gixus Alt a r s of th e Philaeni

Car al i s C L epci s

Carthage ag e drumet u m Ha H a g Utic a

Hi p po Re g i u s Oea (T ripoli) li)

Sa b bratha

Gadi r ( Cádi z ) s Ti n ngis M a l ac a (Málaga)

In ages gone an ancient city stood – Carthage – a colony of Tyre, from afar it faced on Italy and on the Tiber’s mouths; vast was its wealth and revenues and ruthless was its quest of war.

Virgil, Aeneid 1.12–141

Any story of Carthage must begin with Dido. In myth, she was an enduringly beautiful queen whose tragic life has been recounted across the millennia in literature, art and music. In history, she was a woman who lived in the ninth century B c E and came from Tyre, a city in modern- day Lebanon. And she was not really named Dido. The people of Tyre spoke Phoenician, a Semitic language of the eastern Mediterranean that was written in an alphabetic script. In the Tyrian native tongue, she was known as Elishat and when the Semitic name Elishat was transcribed by the ancient Greeks it turned into Elissa, which is how some ancient Greek historians refer to her. It was as Dido that she found eternal fame in the Roman stories, and there are many different views on why the Romans took to calling her by this name. The most convincing explanation is that Dido was a kind of surname or epithet meaning ‘the wanderer’, which may be a

nod to how she travelled across the Mediterranean before she reached the place where Carthage was founded.

The Roman poet Virgil immortalised the most famous version of the foundation legend of Carthage in the Aeneid in the first century B c E , but this was eight centuries after the event itself and over 100 years since Carthage had been destroyed. Virgil took a pre-existing story of Dido/Elissa and wove it together with one of the foundation myths of Rome – entwining the two cities for posterity. In Virgil’s epic, the Trojan hero Aeneas, after escaping the burning city of Troy, takes refuge on the north coast of Africa, at Dido’s Carthage, just as the city is being constructed. Aeneas’ sorry tale of Troy’s destruction plays on Dido’s sympathies and the two become star- crossed lovers, doomed by the gods to be separated. Dido is seduced by Aeneas before he abandons her, leaving the Tyrian queen heartbroken and full of remorse. Aeneas carries on to Italy, as he follows a destiny prescribed by the gods. This Roman tale turns Dido into the very archetype of a rejected, abandoned and vengeful woman. For this was a profound humiliation for a noble woman, who is left with little choice but to take her own life. It is with her dying breath that she hurls a curse down upon the departing Aeneas and all his descendants. Dido implores that in the future there will ‘Rise some avenger of our Libyan blood’, and in this story a Roman justification was created for the subsequent wars between the two great cities.2

Virgil’s Dido has resonated throughout the ancient and modern worlds, with the tragic queen portrayed in theatre, opera and novels across multiple languages and cultures. But this is not the only version of the story of Carthage’s foundation, and in the other surviving tales there are perhaps more tangible details of the woman who inspired these stories. The earlier versions omit the Roman Aeneas from the story altogether and tell us of the Phoenician queen Elissa. Originating from a Sicilian Greek writer

named Timaeus of Tauromenium (modern Taormina in Sicily), this tale dates to at least the late third century B c E , but it probably existed even earlier. Only fragments of Timaeus’ history still exist, teased out from pieces preserved by later ancient writers, so the complete pre-Virgilian story of Carthage’s foundation remains somewhat unclear. In this version of the story, Elissa was a Phoenician princess from Tyre seeking refuge on the North African coast. She had been forced to flee her home city because of the political turmoil caused by her brother, the young king Pygmalion. Pygmalion killed Elissa’s husband, who had been king regent and chief priest to the Tyrian patron god Melqart. After the murder of his brother-in-law, the young Pygmalion seized the throne of Tyre for himself, but his grip on power was shaky and many of the nobility were not convinced by his rule. This included his sister Elissa, who was horrified by her husband’s death and sacrilege to their gods, and who became a focal point for opposition to the new king among the ruling elites.3 Elissa and her group of rebels fled the city by night, taking sacred artefacts that belonged to the god Melqart with them. They began a long journey across the Mediterranean, heading west to settle in the new colonial lands. The Roman historian Appian echoes these details when he tells us that Dido/Elissa ‘set sail for Africa and took with her property and a number of men who wanted to escape from the tyranny of Pygmalion’. 4 The rebels’ first stop was the island of Cyprus, where they collected young women to join their party as brides. The women came from a renowned temple at Kition dedicated to the goddess Astarte (equivalent to the Greek Aphrodite or Roman Venus); this was a place where a young girl might be sent by her family to serve time as what we have conventionally called ‘a temple prostitute’ in honour of the goddess. After their time in the temple, we are told these young women were considered very eligible brides.

Thus the noble Tyrians and their brides left Cyprus together and voyaged across the sea, stopping in Greece and Sicily before arriving at the place that we know as Carthage.5

What to do with these fragments of a long-ago myth, filtered through the lens of Carthage’s enemies? And how do we interpret them? The essential elements of the story that survive, from the gathering of women and the appropriation of sacred objects, suggest this was no mad flight across the sea but a planned expedition. This fits into what we now understand about early Phoenician settlement and the evidence from other sites like Cádiz in Spain that show urban foundations and organised city planning.6 The fact that Carthage would continue to pay tribute to the temple of the god Melqart at Tyre throughout its 600-year existence makes it clear that this was a move with colonial intentions; an annual tithe points to a close and very specific relationship with the mother city. There are hints in the stories of Elissa/Dido’s relationship to her dead husband, as well as his worship of Melqart and her enduring fidelity to him, that give us building blocks for the ideas behind the foundation of the city of Carthage. The name Melqart literally means ‘king of the city’, and he would play an important role through the whole history of Carthage. Melqart’s role was as protector of the city and its new colonists. He was part of the divine pantheon of the religion of Carthage but also associated with other Phoenician cities in the west. This made him a focal point for a community identity and one that would spread across the whole western Mediterranean. So, embedded in these myths of the founding queen Dido and her idealised female virtues is information about the choices made by the Tyrians who settled in Africa.7

Carthage’s mother- city Tyre was a vital centre in antiquity, a regional power with monumental architecture and a sophisticated port. The later Greeks and Romans have left us various

descriptions of it, like Quintus Curtius Rufus who notes in his History of Alexander that Tyre was ‘memorable among all the cities of Syria and Phoenicia for its renown and size’.8 It was a dominant force in the eastern Mediterranean Sea and hinterland regions, and the Tyrian population would have carried this fame and pride in their origins with them to establish their new cities in the western Mediterranean. Set just off the coast of the Levant on an island, Tyre was a classic location for a Phoenician city: protected from the mainland, easily accessible by sea and offering good shelter for ships. Carthage too shared these attributes. In fact, the name Carthage in the Phoenician language was Qart Hadasht, which means, literally, the New City.9

Carthage was not the first Phoenician city on this coast of Africa. Just 30km to its north was Utica (see page 10), founded, according to ancient historical sources, some centuries before Carthage. But our archaeological evidence from Utica does not match up with these earlier recorded dates and the city may have been there for only a few decades when Carthage was established. The pottery, mostly drinking cups and plates, found in excavations at Utica are stylistically dated to a contemporary period, the ninth century B c E , and the results of radiocarbon dating make it possible to push the occupation back slightly earlier – into the tenth century. One spectacular recent find uncovered the remains of a whole feast held by the people who lived in Utica in these early years. The population had slaughtered, roasted and consumed goats, oxen, pigs, horses, turtles and a domestic dog in a communal meal. Then, after the dining and drinking, all the plates and cups were gathered up and deposited – along with the animal remains – in a deep well. The reason for the feast and deposit made afterwards may never be known but the theory is that the community held some kind of ritual closing of the water source. Thousands of years later, these remains found by

archaeologists provide all kinds of insights into the early African city and the engagement of the population with the world around them.10

The pottery and tableware used at the feast at Utica came from across the central Mediterranean and tell us that the people there in these early years were in contact with neighbours to the north in Sardinia and in central Italy, and to the east in Greece and the Levant. They were very well connected and had been busy trading across the seas. So, we have to ask, why was Carthage built just some 30km to the south? The answer lies in its location. Although an inland site today, Utica sat on the coast in the ninth century B c E where the course of the Bagradas (Medjerda) River met the sea. The river’s annual flow meant that the harbour of Utica, right at the river’s mouth, constantly suffered from silting and the likelihood is that Carthage was chosen as a more easily accessible and functional port.11

Once the new colonists arrived in Carthage, the local inhabitants, referred to variously in our ancient sources as Numidians or Libyans, seem to have been somewhat resistant to another settlement. The indigenous peoples would have already had dealings with the settlers from the Levant in Utica and were not welcoming to Dido and her followers. In fact, Dido and the new arrivals are believed to have tricked the locals into giving up their land. In the myth, which is recorded by a much later Roman source called Justin, Dido bargains with a local king for a piece of land, asking only for ‘as much land as could be covered by a single hide of an ox’. Dido tells the king that she is only going to use the land to rest her people who are tired after their long journey from the east. Then, she secretly has the oxhide cut into the thinnest possible strips. Laying each thin strip end to end, she encircled as much land as she could, and in doing so acquired a lot more land than she had first seemed to ask for. The piece of land acquired by

the lovely queen was afterwards called the Byrsa, and this became the citadel of Carthage – for Byrsa in Greek etymology means ‘hide’. Justin doesn’t tell us about the Libyan king’s reaction, but he could hardly have been thrilled at the deception.12

The story of the oxhide seems outlandish to us but was frequently repeated by ancient writers to showcase Dido’s clever ruse in outwitting the local king. The Carthaginians would be eternally characterised as tricky, deceptive and untrustworthy, but some scholars believe there may be a modicum of truth in the tale. It may be that the oxhide story echoes a contemporary legal process of land acquisition we have no knowledge of, and mixed with it is a much better-known concept of using an ox to plough an area of land to mark out boundaries. But questions about the story remain. For instance, why would Tyrians, whose language was Phoenician, use a Greek word like Byrsa for their citadel? Here we can see the layers of text and traditions at work as a story from a prehistoric past is woven into the tale of the foundation of Carthage. The Phoenician word for fortress is barsat and some experts argue that Byrsa is a corruption of the original Phoenician word made sensible for a Greek audience. This version of the story shows us how ancient Greek writers tried to understand the Carthaginians within their own mythical and linguistic frameworks.13

In all versions of the myth, death comes to Dido by her own hand. The city she founded grew and prospered so much that a neighbouring king named Iarbas took the opportunity to seek out marriage to the queen. Dido refused his offer, claiming she could never break the vow she had made to her long dead husband. More realistically, her decision likely reflected the vulnerability of women rulers at the time, and she did not want to hand over her autonomy and power to Iarbas. The elites of Carthage had other ideas and Dido’s followers were, as the story goes, supportive

of the marriage proposal. This tale reveals a lonely queen who struggled for power and needed to secure the city through the support of a man. The population would have wanted a leader to produce heirs, and here is the timeless tale of a reigning childless queen pressured from all sides. It began to look as though Dido would be forced to marry, that the elites around her were ready to overthrow her if she refused. In the legend, Dido chose to kill herself rather than be forced into this unwanted marriage. In the final scene, she throws herself on to a burning pyre and in her self-immolation embraces a symbolism of great sacrifice, female virtue and modesty.

These many stories of Dido have left a complex and conflicted image of a woman who is both virtuous and self- sacrificing, powerful and creative, but at the same time someone whose passion and love led to her destruction – at least in Virgil’s story. Can the variant versions of Dido tell us anything about Carthage or are they only useful for understanding Roman ideas of female power and virtue? There are parallels in the story with one of the only other Carthaginian women we know anything about, the wife of Hasdrubal, who we talked about at the very beginning of the book and who dies in the same way, and on the very same spot –the Byrsa hill. There are layers of literary construction underpinning the story, resting in the ideal of a selfsacrificing woman and even similarities to the character of the noble Lucretia from early Roman mythology whose suicide set in motion the creation of the Roman Republic.14 The contrasting version of Dido in Virgil’s Aeneid presents a less-than virtuous queen who uses emotional and sexual temptation to try to lure the proto-Roman Aeneas away from his destiny. The depiction of a temptress Dido, leading a noble Roman astray, has been frequently linked to the figure of Cleopatra, who loomed large in the mind of Virgil’s contemporaries when this story was written

down in the late first century B c E . This is the most enduring of the Dido myths and was written with the approval of the first Roman emperor and great propagandist, Augustus, who had just come to power by defeating the forces of Cleopatra and Marcus Antonius at Actium in 31 B c E . 15

In the mythology of Dido, then, there is a mix of component parts that combine later Roman characterisations of Carthaginians as tricky and untrustworthy with the strength of character and nobility of action that we see more commonly in stories of great Roman virtue. The depiction of Dido’s life captures all the issues that a history of Carthage must contend with, for what the Carthaginians believed about their own foundation is not recorded and how the Carthaginians saw their own history has long been erased from memory.

Beyond the myth, the facts about the foundation of Carthage are only slightly less dramatic. A trail of early Phoenicianspeaking merchants and travellers from the coastal cities of the Levant leads to the western Mediterranean over the ninth to seventh centuries B c E . The reason behind this movement was a complex combination of the shifting need for resources, population pressures and external political factors. The city-states of the Levant that made up the region we refer to as ‘Phoenicia’ turned to trade and colonialisation as a way of alleviating issues at home. This led the population of these places to establish many cities in the western Mediterranean, and chief among them was Carthage. Deep excavations into the earliest layers of Carthage now confirm that a city was founded at a time that corresponds with the ancient sources who claimed these events occurred in circa 814 B c E . 16

Carthage sat on a prime location for a connecting city: midway along the north coast of Africa near the island of Sicily, which formed a kind of natural land bridge across the central

Mediterranean linking Africa to Europe. Since successful maritime navigation in antiquity was based on the winds and ocean currents that could be devastating if miscalculated, ships moved from port to port and always kept land in sight. From Carthage there were easily predicted currents and visible land that carried ships from Carthage to Sicily in the best sailing months. The location also meant that whoever occupied Carthage could control the comings and goings across the Mediterranean’s central zone (see page 10).

If you go to Carthage and stand on the Byrsa hill looking out to the Bay of Tunis today, you immediately see that the geography was ideal, as it is both open and protected. The city sits out on a small peninsula, tucked away to face slightly southeast but at the same time with full access to the sea.17 In antiquity, the peninsula was entirely surrounded by water and the link to the land was much narrower than what we see today. Much of what is currently visible to the north and the south of the narrow peninsula is reclaimed, silted-up land. There was the ideal mix of sea, shelter and agricultural land and as a location for a city it was perfect – and also perfectly Phoenician. In the early period of Carthage’s existence, from the ninth to the seventh century B c E , the sea was a very dangerous place to be settled upon and coastal towns were vulnerable. So there needed to be a balance of location that allowed for maritime travel and protection from the potential damage caused by piracy, invasions and the equally destructive power of storms.

In fact, every time I have visited another Phoenician city culturally linked to Carthage, places like Cádiz, Palermo, Tyre or Motya, I have had that same feeling of being both a vulnerable coastal site, but also a location protected by the very sea surrounding it. There is an inherent similarity between these cities founded by early Phoenician explorers in the Mediterranean, and the only

way to really understand early Carthage and its foundation is to look more closely at the other Phoenician-speaking peoples and their role both in North Africa and across the seas. Since in these early years Carthage was only one of many cities in the western Mediterranean, how it evolved out of a group of related Phoenician settlements, colonies and trading posts to become a power is a key part of the story. To understand Carthage, we need to understand who the Phoenicians were and why they moved into the Mediterranean and settled in these regions.

The people we call Phoenicians are believed to be related to those called the ‘Canaanites’ of the Hebrew Bible, from the land of Canaan of the second millennium B c E . In the late Bronze Age, the Canaanites played an integral role in the movement of goods around the eastern Mediterranean and the Aegean. Evidence for this travel and trade comes from shipwrecks, one in particular found just 50m off the shore near the town of Uluburun along the southern coast of Turkey in the Bay of Antalya. At a depth of close to 50m but clearly visible to divers in the blue Antalyan sea was the ship’s cargo, scattered across the seabed. The detritus of a Bronze Age ship can tell us about the people on board and the routes taken by these intrepid travellers over 3,000 years ago. On board this ship were 10 tons of copper ingots, ceramic jars full of wine from Cyprus and oil from the Levant, glass beads, an Egyptian scarab of Queen Nefertiti of Egypt, and Aegean pots. From the range of these objects, we can tell that the ship had been on a circular route around the eastern shores of the Mediterranean, picking up and dropping off cargo. The Canaanites disappear from historical view in the late second millennium B c E . The theory is that at the beginning of the new Iron Age (i.e. in the tenth/ninth centuries B c E ), they re-emerge in the historical record as the people we now call Phoenicians. These ‘Phoenicians’ lived in cities along the east coast of the Mediterranean

and would have referred to themselves by their city of origin, including the flourishing urban port centres such as Sidon, Tyre, Beirut and Byblos.18

We only call them Phoenicians because the later Greeks did – they never referred to themselves that way. The name comes from the Greek word phoinike , which is associated with the colour purple and linked to the extremely valuable purple-red dye they were known to produce. The manufacturing of this dye was a key industry in ancient Phoenician cities, with the precious ink coming from a process of grinding the now almost extinct murex shell. There are references to the word Phoenix/ Phoinix very early in Greek literature, and a man named Phoinix turns up in Homer’s Iliad as an elderly councillor of Achilles. Elsewhere Phoinix is, in the Greek tradition, the eponymous founder of the Phoenician peoples.19 In the earliest Greek texts, Phoinix was also the father of Europa, who, in mythology, was a princess, raped and carried off by Zeus and brought to the island of Crete. Europa is another of the female Phoenicians of myth and legend who has resonated through Western culture and art. These stories show how contemporary Greeks came to understand and embed Phoenicians, their culture and practices into their mythology.

Early in the first millennium B c E these Phoenicians living along the coast were expanding westwards. Evidence of a rapid growth in cities between the twelfth and eighth centuries B c E and of food shortages as early as the tenth century B c E suggests that the population may have outstripped the productivity of the land. The narrow fertile strip that formed the Phoenician cities’ homeland runs about 200km north– south along the coast. It is well watered and protected from the east by mountains known as the Lebanon Massif and the Anti-Lebanon Range that extend over 3,000m high. The geographical features

block the coastal strip from any easy eastward land expansion. These mountains had always supplied plenty of fresh water and famously excellent-quality timber in the form of Lebanese cedars for building ships. As a result of finite agricultural potential and a growing population, the people we call Phoenicians set out for new horizons into the Mediterranean. They were the earliest to reconnect with traditions of interstate economic activity that had flourished in the Bronze Age and began to take advantage of what we see as growing commercial links in the Mediterranean in the early Iron Age (tenth to ninth century B c E ). They moved westward out of the eastern Mediterranean and Aegean to the very edge of the Mediterranean, and perhaps beyond.

The Phoenicians acquired a reputation as great seafarers and developed some of the first decked warships in antiquity. There is a famous image of a bireme, from a relief found at the Assyrian palace at Nineveh (in modern Iraq, near Mosul), that clearly illustrates the use of a decked warship with two levels of oars (see Fig. 1, in plate section). So, in this period we have Phoenicians becoming known as traders and also merchants, artisans and farmers, but even more significant was their role in navigation and naval warfare in the eastern Mediterranean.

At the beginning of the Iron Age, Phoenicians set out westwards, searching for valuable natural resources to be brought back and traded in the urbanised world of the eastern Mediterranean. They acquired raw materials that were then brought east, both as essential commodities and for the production of luxury goods such as gold amulets and carnelian scarab rings, jewelled earrings, bracelets and armbands. New technologies and industries of the Iron Age had shifted the supply chain and demand for raw materials. The iron- ore deposits of the western Mediterranean became key to the prosperity of those civilisations in

the east. Exploration in the western Mediterranean, particularly in the Iberian Peninsula (modern Spain and Portugal), Sardinia and Etruria (central Italy), led to the Phoenician exploitation of rich natural resource deposits and an increasing reputation for great wealth.

A combination of all these factors seems to have driven the settlement of the western Mediterranean by Phoenician-speaking peoples. The early Iron Age kingdoms of Assyria, Egypt, Israel and Judah, and their relationship to the Phoenician cities, underlie our understanding of these events. There is a famous relief from the palace of the Neo-Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (ninth century B c E ) at Nimrud (ancient Calah or Kahlu on the east banks of the Tigris) where we can see what is thought to be a Phoenician paying tribute to the king (see Fig. 2 in plate section). Accompanying him are two monkeys, one carried on the man’s shoulder and the other led by hand. Are we looking here into the face of an early Phoenician ruler bringing exotic gifts to the great Assyrian king? We can’t know for sure, but we can see how the Phoenicians became associated with these ideas of exotic animals and exploitation of resources from faraway, with the foreign, all symbolised by the monkeys from the west of Africa being presented as tribute.

The nature of the early Phoenician expansion is much simplified in some literary sources where well-known passages in the Hebrew Bible note the wealth available in far-off lands: ‘Tarshish was thy merchant by reason of the multitude of all kind of riches; with silver, iron, tin and lead, they traded in the fairs,’ says the book of Ezekiel.20 By the sixth century B c E , when the Hebrew Bible was written down, the sources of their great wealth are listed as silver, iron, tin and lead; many of these were to be found in the western Mediterranean, in Spain (tin, silver) and in Etruria (iron ore, copper).

The best way to think about this complex web of Phoenicians is to look at the sea routes taken by sailors and merchants around the Mediterranean in these years. The way it worked is that a ship would move from port to port, region to region, dropping off and picking up goods along the way, never straying far from land. The process is called cabotage and the merchants who plied the shores of the Mediterranean not only drove trade, but also increased interactions between cultures. This shows a circular, counterclockwise navigation of the sea that accommodated winds and currents (see page 10). The location of the place called Tarshish in the Hebrew Bible is thought to refer to Tartessus, a region in modern Spain beyond the Pillars of Herakles (Strait of Gibraltar) northwest of the early Phoenician colony of Gadir (Cádiz). This, the Rio Tinto region, is an area set around the Guadalquivir (River Baetis in antiquity), rich in mineral ores even today. This land of great value was prized for its resources, and it is no coincidence that centuries later it would see some of the fiercest fighting between the Carthaginians and the Romans in the Second Punic War: two powers battling for the abundant natural resources of this wealthy region.

The locations of the first Phoenician colonies and settlements were on Cyprus and then Crete, Greece, then on to Sicily, Sardinia, the Balearic Islands and on to Gadir. The return route crossed the north coast of Africa and to Utica, Carthage, the cities of the ‘emporia’ (in Libya today), the Nile Delta and back to the east coast cities of the Mediterranean. Spain, Portugal, Italy, Malta, Greece, Cyprus, Turkey, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Israel, Palestine and Lebanon all have sites with Phoenician origins. Phoenician cities are often still cities today: they chose the locations for them so well that across the Mediterranean there are thriving modern cities from Beirut to Palermo and Cádiz that rest on their Phoenician foundations.

The Phoenicians’ reputation as traders and merchants stuck with them across the centuries, and ancient sources often comment on their connections to wealth, and gold and silver. Along with these come insinuations and claims of greed and corruption and exploitation. An ancient author named Diodorus Siculus, who wrote in the first century B c E , provides a story of how the Phoenicians came to acquire such great wealth through exploitation of less technologically advanced cultures. Diodorus claims that the Phoenicians would use their sophisticated knowledge of metals and trick the indigenous peoples into exchanges: ‘they purchased silver in exchange for other wares of little, if any, worth.’ Diodorus writes that this was the reason why the Phoenician peoples became so wealthy. They transported the silver to Greece and Asia and ‘acquired great wealth’.21

This age- old tale of colonial exploitation captures how the Phoenicians were perceived by much later writers. Diodorus’ story goes even further and emphasises the idea of extreme wealth when he explains that ‘so far indeed did the merchants go in their greed that, in case their boats were fully laden and there still remained a great amount of silver, they would hammer the lead off the anchors and have the silver perform the service of the lead.’ The image of silver- hewn anchors stuck, and Diodorus’ story emphasises so many of the classic Phoenician/Carthaginian stereotypes told by their later enemies. These stereotypes of greed and dishonesty occur again and again in the Greek and Roman sources in discussions of Carthage.

The Mediterranean in the tenth to seventh century BcE often gets explained by scholars using modern terminology like sea commerce, cabotage or maritime trade, and this presents a false picture of a world that is structured by rules and organised interstate bodies and national governments. Much of what was going on was much more free form, involving individual ships crews

heading out to sea to try their luck, and underlying many of the descriptions is the act of what we now call piracy. The early Greek texts often called the Phoenicians pirates, and it seems likely that if we had similar texts to describe the Phoenician view of the Greeks, they too would be called pirates, symbolised by the Greek god Zeus in the form of a bull carrying off Europa, daughter of the Phoenician king Phoenix, to Crete. Zeus acting for his own pleasure underlies the evolutionary tales of small groups raiding foreign shores, carrying off women. This is embodied in the great Homeric epic of the Odyssey, and many would argue that Odysseus was the greatest pirate of them all. The story reflects much of what was going on across the Mediterranean: men in ships sailing off for adventures and explorations. So, when we read about the foundation of cities and movement of peoples across these seas it is important to understand that the Mediterranean societies of the ancient world we often think of – Carthage, Rome and Greek city-states especially – are being formed in this period, and their DNA is deeply embedded in an identity that combined maritime expansion, myth, legend, piracy, trade and violence.

At this critical moment in the Mediterranean, the Phoenicians’ contact with Greek- speaking peoples creates a spark of cultural fusion we can still see evidence of today. The first place of cultural exchange between Greeks and Phoenicians was undoubtably on Cyprus and there is evidence of this at the site of Kition (see page 10). Geographically, Cyprus was a natural place of dialogue between the Greeks and Phoenicians and is a site of fundamental importance. As we have already seen, at Kition was a renowned temple set up for the worship of a goddess. We refer to her as Astarte, a near eastern deity, who became identified with a local goddess by Phoenician speakers on Cyprus. Over time, the deity worshipped transformed into the Greek goddess of love, Aphrodite. We saw that in one of Dido’s myths, the young

women from the temple of Astarte/Aphrodite on Cyprus become wives for the new city to be found in Africa by the Tyrian queen. The love goddess Aphrodite (the Roman Venus) was said by the Greeks to have come from the east, as set out in poetry in the origin myths of Hesiod written down in the eighth century B c E .

She came to sea- bound Cyprus, and came forth an awful and lovely goddess, and grass grew up about her beneath her shapely feet. She who gods and men call Aphrodite. (Hesiod 194–5)

This is a vision that still permeates our conceptualisation of the goddess, with the many representations of Botticelli’s Venus surfing on a shell towards the shore (see Fig. 3 in plate section). So, Astarte was an eastern goddess whose transformation into a Greek deity, worshipped as a fertility and sex goddess, gives us a taste of the kind of cultural transformations that were ongoing over the early Iron Age. And even further west, on Sicily, there was a place where Phoenicians and Greeks and indigenous Sicilians interacted and worshipped the goddess at the hilltop site of Eryx (Erice today) on the far west coast. This too would become a place of contention between Carthage and Rome in their later wars.

It was probably on Cyprus that the Greeks adopted the Phoenician alphabet, and there is evidence of this by the eighth century B c E in both Greece and beyond. The connection between the Phoenician cities and alphabetic writing is embodied by the fact that the name of the Phoenician city-state Byblos becomes the word for book in Greek and Latin. In Greek mythology, Cadmus, mythical founder of Thebes and patriarch of the family that gave us the tragic stories of the Oedipus cycle, brought, in the words of Herodotus, ‘letters to the Greeks’.22 The heroic prince Cadmus was known to be a native of the Phoenician city of Sidon.

There is evidence for the transformation from the Phoenician to the Greek alphabet found even further west, in the form of a famous, tatty- looking cup from Pithekoussai (modern-day Ischia, off the coast of Naples). As the first Greek colony in the western Mediterranean, Pithekoussai was a place where cultures mixed and merged during the eighth century BcE. Researchers have found pottery showing Greek geometric forms, along with Levantine ‘Phoenician’ amphorae and central Italian luxury items. But there is also a small, unique ceramic cup that was discovered in a simple cremation grave of a young child, a tenyear- old boy, and which preserves just a few lines of poetry scratched on its side. It is called Nestor’s cup, from these lines that read: ‘I am Nestor’s cup, good to drink from. Whoever drinks this cup empty, straightaway desire for beautiful-crowned Aphrodite will seize him’. This is thought to be a direct reference to a story told in the Iliad, which would have circulated around the Mediterranean as an oral epic, sung by travelling bards and entertainers who plied the shores, following those who settled in the coastal areas. The inscription on the cup is both poignant and self-effacing, in that this little ceramic cup from the grave of a young boy references the heroic Nestor’s golden urn, which was so heavy only a strong warrior could lift it. Even more incredible is that the words are written on the cup in the nascent Greek alphabet, which was, at this early date, still being written from right to left like the Phoenician.23 Here is a captured moment of cultural fusion (see Fig. 4).

In these formative years, we have a Phoenician alphabet being transformed into a Greek one and eastern deities adopted into the pantheon of the Greek world. Just these few examples, stories and myths from the early Iron Age and the archaic western Mediterranean world hint at the vibrant environment of trade, exchange and exploration that was going on. The Phoenicians were vitally

important players in connecting cultures and carrying ideas across this landscape.

So, beyond the myths and stories, these are all the facts that underlie the foundation of the city of Carthage in the ninth century B c E . There is little specific detail from this proto-historic period; during the first three centuries of its existence Carthage barely registers in deep legend. But these stories of early Phoenicians and their interactions across the vast reaches of the Mediterranean nevertheless contain the origins of the city and seeds of its people and its power. Over the next few centuries, we know very little about what happened at Carthage, much less who succeeded Dido and how the city was governed, how many people lived there or what they thought of themselves. This is true not just of Carthage but of the whole Mediterranean; most of what we know from these formative centuries is steeped in the myths and creation stories of Greeks and Romans written down

hundreds of years after the events. We will have to wait until the sixth century B c E before we can differentiate between Carthaginians and Phoenicians and can begin to say who her people – the first real Carthaginians – truly were. To fill in the gaps, I think that looking more carefully at archaeology will help to give us a tangible idea about what was happening in Carthage, about who lived there and what they might have believed and valued. This kind of information, while not necessarily tied directly to a historical figure, can enrich the story with ideas of people who lived and breathed in the city, and the houses they lived in, their contacts and trade, their career options and religious beliefs and hopes for the afterlife. It is archaeology that helps us to link the mythical beginnings with the rise of the city that would become the great power of Carthage.

3rd c. BCE Wall

Byrsa MEGARA Gulf of Tunis ISTHMUS Triple Wall

Main map area

Bordj Djedid Cemetery

Byrsa Cemetery

Hill of Juno Byrsa Hill

Houses Temple of Eshmum

Bir Massouda

Quartier Magon

Sea Wall & Gates

Ancient Channel to Lake of Tunis Tophet Southern Wall

Modern Shoreline

Military Harbour

Commercial Harbour

Cemetery 8th/7th c. BCE City Wall

01000 m