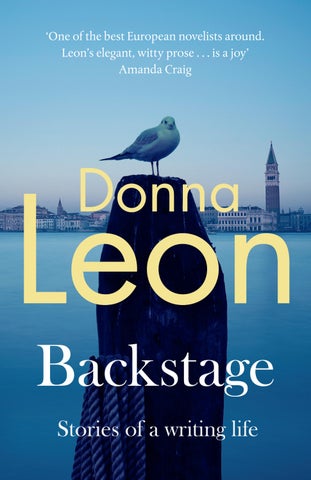

‘One of the best European novelists around. Leon’s elegant, witty prose . . . is a joy’

Amanda Craig

Also by Donna Leon

Commissario Brunetti Mysteries

Death at La Fenice

Death in a Strange Country

The Anonymous Venetian

A Venetian Reckoning

Acqua Alta

The Death of Faith

A Noble Radiance

Fatal Remedies

Friends in High Places

A Sea of Troubles

Wilful Behaviour

Uniform Justice

Doctored Evidence

Blood from a Stone

Through a Glass, Darkly

Suffer the Little Children

The Girl of His Dreams

About Face

A Question of Belief

Drawing Conclusions

Beastly Things

The Golden Egg

By Its Cover

Falling in Love

The Waters of Eternal Youth

Earthly Remains

The Temptation of Forgiveness

Unto Us a Son Is Given

Trace Elements

Transient Desires

Give Unto Others

So Shall You Reap

A Refiner’s Fire

The Jewels of Paradise

Wandering Through Life: A Memoir

Hutchinson Heinemann

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Hutchinson Heinemann is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW

penguin.co.uk global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published 2025 001

Copyright © Donna Leon and Diogenes Verlag AG , Zürich, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset in 10.4/15pt Palatino LT Pro by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978–1–529–15514–3

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

For Anna and Frank Bonitatibus

This is life: people are strange. And from that comes the realization that, to many people reading our character, we can seem just as strange.

Early in Life

Cedric

Although he might be well into his sixties by now, my guess is that Cedric, according to statistics, is probably either dead or imprisoned. Cedric was Black and lived in America, so the odds were against him from the beginning. From long before the beginning, it might be clearer to say.

I met him in the 1970s, when I was in my thirties, living in Bloomfield, New Jersey, and attending night classes to finish my master’s degree in English Literature. I supported myself by working as a substitute teacher in the elementary schools of Newark, New Jersey, a city that had the highest infant mortality rate in the country. It was about ten kilometres from where I lived, but it might as well have been on the moon, so different was Newark from the cities around it.

Cedric was one of the students in a third-grade class I was asked to teach for a month. He must have been ten, no more than that, and thin, as if his body had decided to use the energy available to it to grow tall, even if he had to be thin to do so. His skin was medium brown, and he had curly dark hair, cut very short. His eyes were a bit lighter

than his hair, and his hands were never still. His smile, which I suspect appeared only by accident, was lovely yet somehow guarded: his normal expression was a worried nervousness, something that belonged anywhere but on the face of a ten-year-old.

The school in which I taught was made of red brick, just like the school in the third-grade ‘reader’ we used. It was in a city that even then had a majority Black population, although the city government was still in the hands of the descendants of the millions of Italians who emigrated to the US in the early twentieth century.

The Black population, far greater in number than the white, had no political clout. This was the US in the 70s, and that was the way things were, even though the Black residents had rioted for days only three years before. His Honour the Mayor had recently been convicted of conspiracy and extortion and was currently serving time as a guest of the state, but Newark being the kind of place it was, such things did not disturb the citizens of the city, and surely not the members of the faculty of the Franklin School.

There were about thirty kids in the class I was given to teach, not that I had any idea of what third-graders were expected to know, nor was any suggestion provided that might have advised me how to teach them. Half of the kids were girls, half boys; most of them were Black. Some background information is needed here. There had been one Black student in my own elementary school

class, none in my high school or university classes. I had no Black friends because segregation worked and kept us far apart, as separated and incomprehensible as creatures of different species. Protest against racial injustice was seen, by white people, entirely on television, it being a reality they did not suffer. The few times I’d travelled in the South, visiting family, I’d been startled by signs indicating that certain drinking fountains, buses, restaurants, beaches and just about any place where humans congregated were strictly segregated. The only explanation I could wrest from my parents, people of a liberal cast of mind, was a falsely neutral, ‘People are different down here.’ I might as well have been living in Cape Town. I was the grandchild of immigrants. My family name was once de León, but both the ‘de’ and the accent disappeared at the port where my paternal grandfather entered the United States from a South American country the name of which he never mentioned. Nor did he ever speak to any of his grandchildren in Spanish. He came, he saw, he started down the gangplank, and by the time he got to the bottom and stepped away from the boat, he was American and accepted as such. Because he was a well-educated and successful businessman, and because he looked like everyone else, he was never the victim of prejudice of any sort, nor did his grandchildren, sheared free of that foreign name, even know what prejudice was. Cedric, born American, had none of these advantages. Often absent from class (we didn’t have to report a

student’s absence until the third day), when he did come, he usually sat and looked out the window. As I recall, he was always eager to be the one to read out loud from the prescribed ‘reader’, within whose pages Jack and Jill went up the hill and Farmer Brown loved his cows. He read aloud in a clear voice, had no difficulty in pronouncing words, and added a note of drama to the voices of the various characters. These were his good days.

I came to recognize and profit from them by asking the class if they wanted Cedric to be the first reader that day. Other days he came and sat at his desk, looking out the window and not participating in any of the activities except the single hour of outside exercise, when the boys gave an example of what appeared to be demonic possession and the girls sat on a long bench and talked to one another. And then there were the bad days, perhaps one a week, when he would – with no apparent reason – fall into a frenzy of violence, always careful to choose to start a fight with a student larger and stronger than himself.

At the beginning of my second week, Cedric began to materialize in the lot where I parked my car and walked with me to the school. Twice he took my hand and held it until we were one street from the school, when he disappeared.

It took me only a few days to realize that the kids and I lived, and had always lived, on different planets. I was a middle-class white woman upon whom life had showered uncountable blessings, while these were poor kids who

Cedric

wore the same clothes to school all week and devoured the school lunch in minutes. Just as fish don’t take samples of the water in which they swim, most people then didn’t – and I fear don’t now – pay attention to the rules underpinning the society in which they lived.

I’d grown up no more than ten kilometres from where Cedric lived. While I was learning how to distinguish a Shakespearean sonnet from a Spenserian one, he was mapping out the violent territory in which he lived.

One morning during my last week with this class, one of the other boys told me that Cedric, who had apparently raised the calibre of his anger, had brought a knife to school, saying he was going to stab another student. When I asked Cedric to give me the knife – I wasted no time with questions – he slapped first his right hand, then his left on his pocket while heatedly maintaining his innocence.

I held out my palm, and after very little resistance, he handed me a pocket knife with a blade long enough to peel a grape. He then surprised me, and the other students, by walking across the room and standing behind the open door of the classroom, as if he had acknowledged his guilt and would now begin serving his sentence.

Two boys at the front of the room used this distraction to start screaming at one another, and then they were rolling around on the floor without appearing to want to do much damage to each other. I pulled them to their feet just as the three o’clock dismissal bell rang, and never had even the voices of angels been so sweet and welcome.

BACKSTAGE

The kids lined up, careful to let the girls go first, and filed quietly out of the room and down the stairs, leaving me behind. They did not erupt until they were outside the building, but by then it was after three and they were no longer my responsibility. Incapable of motion, I stood and stared at the closet doors at the back of the room, where posters of Lenni- Lenape Indians showed the original owners of the land now called New Jersey. Yes, feathers in their hair, faces and bodies painted the same colour as Cedric.

Cedric.

Behind the door.

I called his name, started towards his hiding place, then stopped and said, ‘Hey, Cedric, that was really a big one, huh?’

There was a shifting noise.

‘You want a ride home?’

When there was no shifting noise, I added, ‘I‘m beat. You must be tired, too.’

There might have been a noise, so I asked, ‘You wanna help me close the windows?’

The door moved as he slipped out and made towards the windows; he closed half of them carefully and silently, leaving me to take care of the higher ones. We left the school together, both of us wearing jackets and scarves against the autumn chill. He must have known where the car was, for he led the way, and once we both got into the red VW, I asked him to tell me how to get to his home.

Cedric

‘Left. Now right. Up there on the right there’s a place to park.’ There was, and I did.

We got out. He closed the door carefully, no slamming. I did the same.

The houses were all the same: narrow, wooden, paint peeling everywhere, steps cracked, more peeling paint.

He pulled out a key on a chain he wore under his jacket and turned it in the lock. He opened the door and stepped back to let me enter first. More peeling paint and one or two wobbly steps, a very untrustworthy railing.

My brother once kept hamsters. The smell was the same: powerful, chemical, rich with urea. Cedric stopped on the second floor and knocked a few soft times at the door on the left.

A noise came through the door, a key turned, then another higher up, and then it was pulled open. She was stunned by the sight of me and failed to hide it. Her expression opened with fear, moved to suspicion, and finally settled into curiosity. She was tall; her eyes and mouth left no doubt that she was Cedric’s mother.

‘This is my teacher,’ he said.

Her face softened, as at the removal of peril.

‘Would you like to come in, ma’am? Can I get you a glass of water?’

I gave what I thought was a smile and said, ‘Thank you, ma’am, but I’ve got to go back to the school. Forgot some papers.’

As if I’d not spoken, his mother pulled the door fully