‘A bold, beautiful, confronting journey’

Isabella Tree, author of WILDING

‘Extraordinary … A global story told through the lens of one species’ Tobias Jones, author of THE DARK HEART OF ITALY

‘A bold, beautiful, confronting journey’

Isabella Tree, author of WILDING

‘Extraordinary … A global story told through the lens of one species’ Tobias Jones, author of THE DARK HEART OF ITALY

HUTCHINSON HEINEMANN

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Hutchinson Heinemann is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London sw11 7bw penguin.co.uk

First published 2025 001

Copyright © Adam Weymouth, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted Maps by Ulli Mattsson

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Set in 13.5/16pt Garamond MT Std

Typeset by Jouve (UK ), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d 02 yh 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn : 978–1–529–15194–7

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

This one’s a love story, and it’s for Ulli

I will send wild animals against you, and they will rob you of your children, destroy your cattle and make you so few in number that your roads will be deserted.

Leviticus 26:22

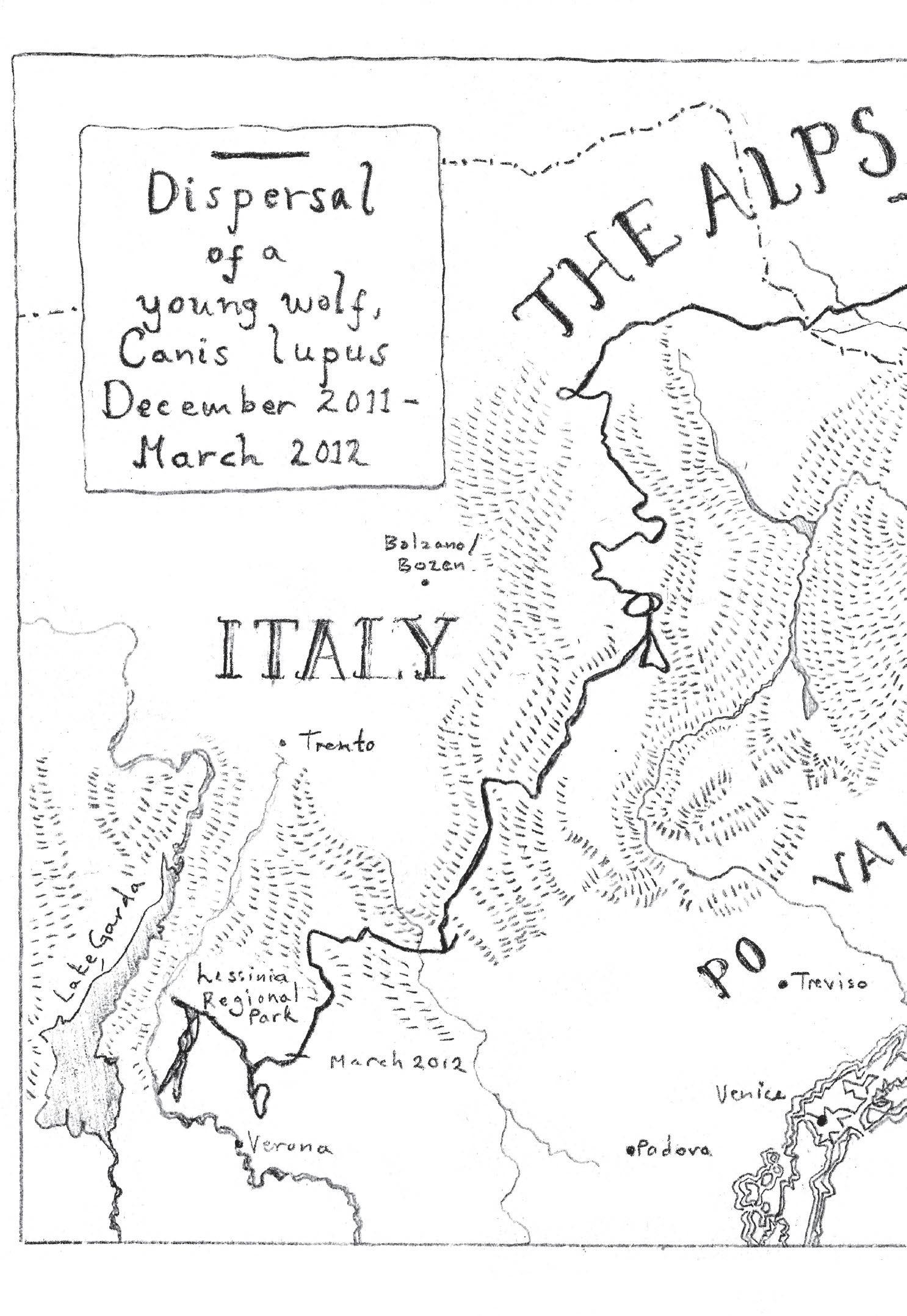

In 2014 I walked across Scotland to research how people living there felt about the mooted possibility of wolves being reintroduced into their country. During the course of that research, I came across a small piece in The Guardian by the journalist Henry Nicholls. It was an interview with Hubert Potočnik, Associate Professor at the University of Ljubljana, about a wolf called Slavc who had walked across Europe. Several years later, having returned from Alaska for my previous book, I began thinking about that wolf’s journey again. I first travelled to Lessinia – a Regional Park in northeast Italy where Slavc had set up home – in 2019, but soon afterwards coronavirus made further research impossible. It wasn’t until the beginning of 2022 that I made it to Slovenia and met Hubert for the first time. Most of the research for Lone Wolf was carried out during that year, although I returned in 2023 to a number of places, often with a translator, to carry out more in-depth interviews than my patchy Italian, or non-existent German and Slovenian, had allowed when I first passed through. Other interviews I expanded with subsequent conversations on the phone. I also travelled to Lessinia several times over the course of those two years.

Unlike Slavc, I had two small kids by the time I set out to follow in his footsteps, and I was reluctant to be away from home for more than a few weeks at a time. I did the walk in several stages, returning to England in between. I have written about the walk, and my time in Lessinia, as one continuous journey, in order to preserve the flow of the story that I wanted to tell.

Statistics concerning wolf populations and predations, and the current state of European politics, are as accurate as can be at the time of sending the book to print, in late 2024.

Some locations and characters’ names have been changed to protect people’s identities.

The wolf left in the winter.

The days are short at this time of year and the nights are very long. Since dawn the light has been held within a fist and now it is close to extinguished once again. The wolf makes his way along the shallow gully, moving counter to its gradient, loose-limbed, his ankles loose and flickering. Were you to balance a glass of water between his shoulder blades, it would not spill a drop. There are no birds, and the bare poles of the beeches recede into the darkening wood, push up into the thin, metallic sky. The snow down here is grey for lack of light. There is nothing moving, no life, except for him.

The wolf moves precisely. Each print that he leaves is the size of a saucer. This small pocket of wood makes up one stretch of the western boundary of his pack; its other perimeters are many kilometres away. He has been moving all day, pacing its border on a southerly bearing, alongside the railway track. Since dawn he has scarcely broken pace. He is an animal built for motion; this is, perhaps, his supreme quality. He has not killed for eleven days, but that does not matter much; he can

go for far longer than that. Beneath his fur he is taut and lean, but his coat is as thick as it will get all year, a dense underfur clad by a thick layer of guard hairs, and however thin he gets he will not be cold, not yet, not until he begins to metabolise his muscle. For now he is only keen and focused. His coat is tan and steel and crow-black and snow-white, a palette drawn from the colours of the landscape, and he has black markings that accentuate his muzzle and run the length of his back as though he has been marked by kohl. It is unimaginable that the wolves were once gone from this place because no animal could belong here more completely. His breath clouds in the cold, hard air. An agglomeration of fine blood vessels engorges his toes and prevents his feet from freezing solid.

He moves across land that is very old. Beside a trunk he halts and lifts his leg and urinates, and then he paws at the ground with all four feet to smear the sweat from the apocrine glands between his toes over the snow. This scent speaks of many things. To another wolf that encounters it, it narrates his sex and age (a yearling, male); his subspecies (Canis lupus lupus ); his social status in his pack (subordinate); his sexual readiness (he is fertile). It gives indications as to his health and diet. To his own pack (which at this moment comprises seven other individuals: his parents, four pups from this year’s litter and another older, unrelated male) it is an olfactory fingerprint unique to him. To other wolves it says keep moving; it says this territory is taken, carry on. If it does

not snow again, this marker will last weeks. There are other, older scents upon this tree, and most recently a female, dominant, in good health. This is his mother. He shakes himself and carries on. In a couple of minutes he stops to mark again, and then he continues, moving upwards, through the naked wood.

He is still young, he is nineteen months old, but he will not be young for much longer now. Winter is the hard season, but the snow places a finger on the scales in favour of the wolves. The rangy deer punch through the drifts up to their hocks, while he appears to glide over its surface with a deftness that belies his weight and bulk. He is full-grown now, forty kilos and standing seventy-five centimetres at the shoulder. He trots across the snowpack, pausing to sniff, pausing to listen. This track that he follows reeks of deer but they are several days ahead. The balance is weighted in the wolves’ favour, but this winter has been hard. The competition for food has been intense. Last winter, when he was a pup, his pack had let him feed. Now there is a new litter to care for. And so increasingly he spends his time alone. Eating a dormouse, eating a fox, eating whatever is left of a carcass once his pack and the pups have had their fill. Poor food.

He pads on. He follows a concertina of twisted razor wire that maps the curvature of the land, still climbing. He knows to avoid its blades; he knows the places that are slack where he can cross. This land has seen the redrawing of borders and the movement of its peoples

since the beginnings of recorded time and longer, and the wolf cares for none of this. But sometimes a deer will get hung up on the fence and that is worth something to him. He snaps at a falling leaf, misses it, and surprised by his own silliness, he trots on.

The wolf moves across the landscape and he seems terribly small within it. His species was sharpened on such environments; whetted by mountains and by limber, rangy ungulates, and honed, too, by his relationship of persecution with man. Wolves seem most wolfish when they are in the grip of struggle – in the winter; in human worlds. He climbs the slope with the same true movement and in time he emerges at the crest. The trees thin and he stares out, his eyes resin-yellow, the stone-black pupils interred within them like mosquitoes fixed in amber. All the familiar landmarks: the television mast, the jagged hills, the sea. The hills that drop away in pleats and down there, beyond the shoreline, the many scattered ships and a chill wind scouring the surface of the water.

His territory is sliced by a four-lane highway, and from here he can pick up its incessant thrum. It is the main road from the capital to the coast and the traffic does not let up. Even if you could hear it – you, with your vastly inferior ears – it might still sound like the wind that barrels from the inland slopes and charges for the sea, or like the background drone of the universe. But to the wolf these man-made sounds hold a particular, charged place. The logging trucks downshifting through

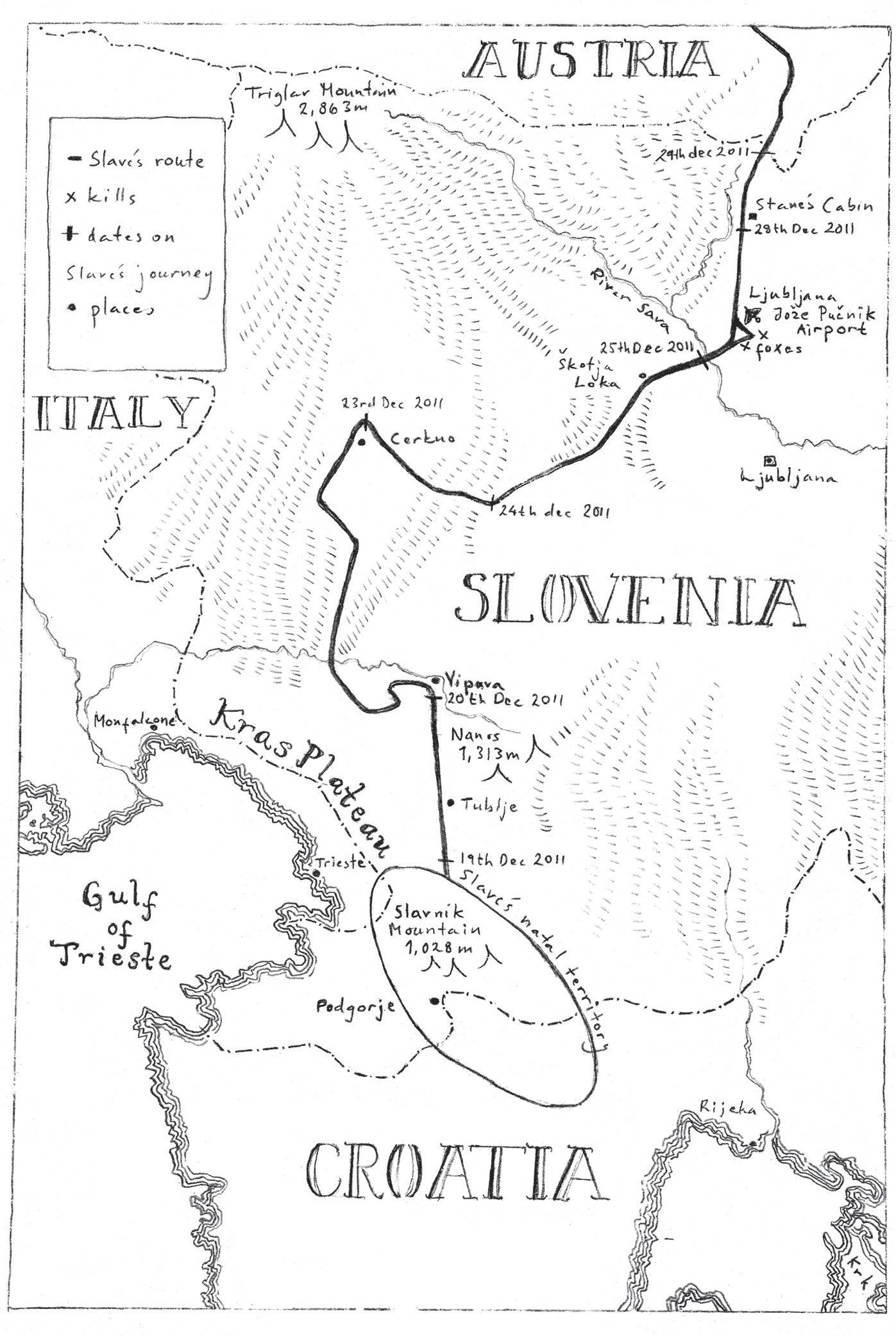

their gears on the inclines, their air brakes gasping. Since he was young he has learnt how to navigate this road; to find its culverts and the rips in its chain-link fence. Along with how to hunt and his place within the pack, these are things that young wolves here must know. They are the things that their survival is predicated on. Everything about this land is utterly familiar. The smells, the sounds, nothing out of place. He learns through difference. In essence, the wolf is a conservative species. He retains a sharp memory of the trap, last summer, his forefoot clamped and the utter terror, and of later waking, woozy, and the awful, human scent all over him, and the thing awkward around his neck. Sometimes he is still aware of the collar that he wears. He will not make such a mistake again. His brother was shot. He saw it happen. One-third of them, at least, die before their first year is out. Already he is a wolf that defies odds. He is conservative, but he is driven, too, by an irrefutable force. A force to eat, a force to breed, a force to live. This, too, his survival is predicated on. And it will be on this same night, 19 December 2011, just after three-thirty in the morning, when for the first time in his life he will set foot outside the boundary of his territory. He will take a bearing north-north-east, following a logging road along the Bukovica ridge, sloping away from Slavnik’s summit. Eighty kilometres away, in a room on the second floor of the Biotechnical Faculty in the University of Ljubljana, a GPS point will appear on a computer screen.

Did the wolf know, in those first foreign steps, the journey he was embarking on? Was he scared of the newness, the strangeness, the difference? Did he know these were the first steps on a journey of several thousand kilometres, a journey of many months?

Did he know, right there at the beginning, that he would never be coming back?

Until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.

Chinua Achebe in The Paris Review

Last autumn was a poor one for beech mast. Some years there is a carpet of nuts so thick that the forest crackles underfoot; other years scarcely any. The beeches coincide their mast years, so that during seasons of abundance the animals cannot possibly eat them all, and at least some will germinate. But the lean years are hard on the bears, which must double their weight before they den. Now, in the middle of winter, in early 2022, I can see their restless tracks, and wolf tracks too, criss-crossing the forest floor. Hungry bears did more damage than the full ones. There had been two attacks this winter already, on a hunter and a jogger. This is what Hubert Potočnik tells me as we walk side by side, through the silent wood. I had arrived in Slovenia five days before. I had cleared customs clutching sheaves of Covid documentation, anxious to have remembered everything, and had taken a late-night taxi into Ljubljana. I was uncomfortably hot beneath my mask. People had begun to travel once again.

It was my first time leaving home since the beginning of the pandemic two years before, and all at once I was back in a foreign country, dropped within its foreign sounds and rhythms. I was giddy with excitement, despite the lingering, amorphous threat. During the past two years of strangeness everything around me had become terribly familiar. Now, stepping from the taxi into the city’s chill night air and pulling off my mask, I felt shocked just that I was allowed to be here.

The following morning, outside my room on Vodnik Square, the market stalls are piled with Sicilian lemons and persimmons, with oranges and blood oranges and tangerines, with dozens of varieties of apple. Bottles of freshly pressed apple juice, of raw milk, of rakia. There are pickled walnuts and pickled beetroot, crocks of sauerkraut shredded thick or medium or thin, heaps of parsnips, carrots, squashes, cheap clothes made in Bangladesh. Hooded crows sit in the bare acacia trees, black against the nothing of the sky. The whole city smells of snow and cigarettes.

Ljubljana has just experienced a second winter with no tourists and it has not been entirely unpleasant. Without the coachloads, the city’s residents have been free to notice the beauty of their streets, instead of fleeing them for the summertime and Christmas. The famous spots – Prešeren Square, the Dragon Bridge – are still deserted. When I buy a postcard to send home, the vendor in his booth congratulates me on my visit as though I am the advance guard of a liberating army, but for myself I feel

like a harbinger, the demise of this new normal in favour of the normal.

For now it is still quiet. A busker opposite the Cathedral of St Nicholas, dressed in a black leather waistcoat and knee-high boots, plays the accordion for no one. At night the streets are empty, my footsteps magnified by the icy air. I stop to drink cheap, local IPA s in the sort of bars that you only find in Eastern Europe, in concrete rooms playing severe techno and graffiti scrawled across the walls. Occasionally, on street corners, I come upon small groups of kurenti, carnival performers dressed in shaggy costumes like bears conceived in the minds of small children, their red tongues lolling, festooned with cowbells and ribbons. They are all men, and there is something of the stag do about them, clutching large lagers and smoking through their masks, drunk and snug. In a month or so it will be Carnival, and they are making their first forays into the streets. In warm restaurants of varnished wood I eat heavy dinners of stew and dumplings, lining my stomach against the cold.

One day I catch a bus to the University of Ljubljana on the outskirts of the city. I am wrapped up and redfaced. Hubert Potočnik greets me in the parking lot, and after two years of speaking on our computers it is a little bewildering to be in front of him at last. He is in his late forties but he looks not unlike the students that he teaches, his face boyish, a neat thatch of curly, sandy hair, and he is dressed in the sort of greens and khakis favoured by outdoorsy, animal types. As though

he could blend into his background at any moment, if his background was the Slovenian bush and not the campus car park. He walks me past the hothouses and into the Biotechnical Faculty and up two flights of stairs to his office.

The room is full of jackal skulls and telemetric equipment. Skis hang from hooks; binoculars; camouflage jackets and caps – all the paraphernalia of fieldwork. Shelves of box files and folders stuffed with papers. Posters of snakes, posters of bats, posters of fish. There is some kind of lizard in a vivarium to brighten the place up a bit, and the office resounds with the chirping of the crickets that it eats, so that the room has the feel of some jungle outpost. Fridges hum. A red deer skull bestrides the back wall, a single paper snowflake dangling from one tine of an antler, the last remnant of last Christmas.

Hubert pours me a coffee from the pot. He asks me about my flight; I ask him about the current Covid regulations, the small talk of modern travel. There is an intense, peculiar smell in the room, which no one mentions, so neither do I. There is a young man at a monitor in one corner, going through videos from his camera traps. Another man is bent over his desk, sorting something unidentifiable. I have always found it intoxicating to be around scientists who are doing what they love, their measured passion quite contagious. Mammals have been Hubert’s love since he was young. After high school, after the war, he sat his degree at this university,

and he has made a home in its halls ever since. He had thought at first that he might specialise in wildcats. But that was before he saw his first wolf.

He was on a field trip. He had woken at dawn and gone for a walk, as was his habit. ‘I had walked maybe two kilometres,’ he says. ‘And then suddenly I saw them. Sixty metres away. Three wolves.’

He leans forward, hands cupped around his mug. ‘I had good weather and a good wind. I had a chance to stay there for twenty, thirty seconds. It was really a long time. They were marking in one place near the forest road. They were marking with urine on a rock on the road. And then they just disappeared. I could hear my heartbeat. You know this vein, here in the neck?’ He places a finger to show me where. ‘I had such adrenaline. Not because of the fear, you understand. Because of the excitement. Because I was able to see a wolf.’

Since then he has seen a wolf in the wild perhaps fifteen times, in the twenty years that he has worked with them (not counting those that he has trapped for research). This is someone who is out in the field every day for several months each year, and he is one of the lucky ones. No, it is not easy to see a wolf.

A woman sticks her head around the door, asking for some research paper. ‘I’m going to leave this door open,’ she says on her way out, ‘because it smells really, really bad in here.’

The lab technician grins and looks up from his desk where he is examining samples of what transpires to be

wolf shit. The smell is wild and earthy, unpleasant in a dark, licentious way. Prodded at in a Petri dish, they can make out what the wolves have been eating. In the lab, it is possible to extract the DNA to build the genotype to identify a specific individual, and from that they can reconstruct its pedigree and figure out the constitution of its pack, the entire family tree. They collect hundreds of these samples in the field: scat, saliva, urine, hair. The bank of fridges is stuffed with them. The science is not far off being able to scrape a footprint to gather enough genetic material for identification – we are shedding DNA all the time. This data gives a pretty good idea about how Slovenia’s wolves are doing. At their most recent estimate there were 137 wolves in the country, spread across seventeen packs (although five of these packs straddle the border with Croatia). In 2010 there were just thirty-four individuals.

The other tool at their disposal is the GPS tracker. The back wall is taken up with a vast map of Slovenia, a stepladder propped beside it to better reach the north. The map is cobwebbed with threads and pins like a police incident board, each thread a different colour, and each bobbin of thread is inked with a name: Bine. Luka.

Jasna. Mala. Each thread, point by point by point, delineates the movement of a wolf that they have collared. Some wolves stay local. Their clusters demonstrate the rigid territoriality of their packs. The red and the blue and the cream criss-cross so tightly as to almost weave a blanket, never leaving the confines of a vicinity

that lies between two massifs to the east. The brown does the same, ranging around an area to the south of the capital like a ping-pong ball set loose within a space. But other threads do not behave like this at all. There is a white that commences on the Croatian border and sets off in a line resolutely west-north-west, marching across the country, before pausing somewhere to the north of Monfalcone in Italy, zigzagging about a bit, and then coming to a halt. A green starts in the west, in Triglav National Park, before making for the mountains to the north of Ljubljana.

But it is the dark-brown thread that draws the eye. Beginning on the Ćićarija plateau in the south-west of the country, not far off the coast, it arcs across the western ranges of the Alps before descending to Ljubljana’s plain, just north of the capital, a few kilometres off from where we stand. From there it turns north, making a beeline for the Austrian border, and vanishes off the top of the map. The last point is pinned where the thread meets the ceiling tiles. The bobbin bears the date 19.12.11. And a name – Slavc.

‘Sh-lough-ts,’ Hubert enunciates for me. ‘Try and say it well.’

I repeat his single syllable, imperfectly.

I imagine Hubert is sick of answering questions about Slavc. There is so much important work being done here, not only on wolves but on the trinity of large carnivores, on the bears and lynx as well. It’s like a band that can never shake its breakout hit, doomed to play it

for evermore. But so be it. It is Slavc that has brought me to Slovenia. It is how I first met Hubert. It is why, after two years of planning, I am here at last. And not unlike the hit song, Slavc was the wolf that got a lot of people into wolves.

I put my coffee cup in the sink. Hubert takes me back down to the car park. Students rush about the campus in the cold. We climb into the faculty’s four-wheeler and take the main road south-west out of town, heading towards the Ćićarija plateau, back towards where Slavc was born. Back to where this whole story began.

There is something remarkable happening in Europe. I wrote my last book about Alaska. I spent five years there, off and on, and five months canoeing down the Yukon. When I came home for the final time, I missed the place with the acuteness of a homesickness. I could not stop thinking about its beauty and its space. I missed the groundedness of people there, the anarchism of their spirit, the way they exemplified both community and self-reliance. I hoped that I could find something similar a bit closer to home. For a time, during Covid, I lived on Scotland’s west coast, and if I squinted right I could almost convince myself that I was back there on the Yukon. The geography, the self-sufficiency, the endless summer light. But where were all the animals? The wolf, the lynx, the bear – they all had made their home on our islands once, but they had all been gone for centuries. The badger cull was once more in the news, and

for the first time I found it terribly sad that our largest carnivore was about the same size as a skateboard.

I did my reading. In Great Britain we lost our lynx circa ad 500. Our bear at around the time of Jesus. There are various dates for the last wolf, but most stories put it in Scotland at some point in the 1600s. The more I read, the more I understood that this story was not confined to Britain. As in so many other ways, Alaska, with its healthy populations of bear and wolf and walrus, was the exception. Large carnivores had suffered almost everywhere, and the wolf, which people have always found the hardest of animals to love, had suffered the most of all.

I had seen a wolf in Alaska, only once. She was walking a logjam at the river’s edge, about her own particular business. Some wizardry of our canoe meant that we drifted past without her seeming to notice us. Her head slung low, that bicycling gait, her coat grey and dun and cream, the same cream as the driftwood. She had paused and blinked and looked about herself, taking a measure of the air. There was a high-keyed hum of alertness. Near the beginning of that journey, it had felt like a good omen.

There was a time when the wolf was the most widespread terrestrial mammal on the planet. Its range spanned the Northern Hemisphere from the tundra to the tropic’s edge, from the Arctic to the deserts of Ethiopia and Mexico. Wolves have an adaptability that is comparable to few animals but ourselves. They roamed

the conifer forests of Honshū, the grasslands of the Eurasian Steppe, the Essex flats, the Adirondacks, the scrublands of southern India. They are as comfortable at fifty Celsius above as at fifty below. There are thirtyeight named subspecies of Canis lupus (although some are now extinct). The petite Arabian, with thin fur and large ears, adapted to the aridity of Oman or Palestine; the huge Tundra, found in Scandinavia’s extreme north, and more than capable of pulling down a moose; the coastal subspecies of the Pacific Northwest, which can swim miles with their webbed paws and eat predominantly fish. There are packs in the Himalayas that never descend below 4,000 metres.

And yet, almost without exception, the crusade against them has been merciless. As soon as humans became herders the wolf was cast as thief, and there have been bounties on its head since the coins have existed to pay them in. In Athens, in the sixth century bc , you could get five drachmas for each male wolf killed, one drachma for each female. Charlemagne was the first monarch to throw the full apparatus of the state behind the wolf’s eradication, forming the louveterie corps in ad 812. That the wolf clung on in France until 1927 suggests something of the nature of the quarry. King Edgar the Peaceful (who ruled ad 959–975) levied 300 wolf skins a year as tribute from the Welsh, and demanded wolf tongues as atonement for certain crimes – wolves were more or less gone from Wales by the end of the first millennium. In England, in 1300,

the Reverend William, needing ‘four putrid wolves’ as a quack cure for the skin condition lupus, was forced to import them from abroad, much to the displeasure of customs. The final definitive record for a wolf in Britain is 1621, a note in the diary of Sir Robert Gordon that ‘sex poundis threttein shillings four pennies [was] gieven this year to thomas gordoune for the killing of ane wolf’, an exceptionally high sum that suggests that demand was far outstripping supply. Several years later a French ambassador complained on a visit to England that there were no longer any ‘fierce animals that require bravery to hunt’. The land had been remodelled in our image. To eradicate them from a country down to the very last animal requires tenacity, a deep familiarity with one’s prey, and maybe hatred.

The methods used manifest the full scope of human invention. There were leg snares, neck snares, pitfalls, deadfalls, sprung-steel traps and poisoned bait. In Ireland they were hunted with wolfhounds, their own treacherous descendants; in Kazakhstan they were hunted with eagles. In Russia a dead calf was hauled behind a sled until the wolves gave chase, at which point they were shot. In Spain they were driven by beaters into pits. In Mongolia the hunters mimicked the wolves’ own calls; in Scandinavia, they attracted them with squealing pigs. In the Arctic they hid a bent bone inside a frozen bait that would spring when it thawed in the animal’s belly, rupturing its insides. By the time the colonists were pushing west across

America, wolves, forever conflated with the wilderness, were by extension being conflated with its original inhabitants. For the Native Americans the wolf had been a complex compatriot, but now a hatred of wolves spread like the Word of God. The divine was no longer to be found in the earthly and the grounded but in a moral authority that could be rolled out, like carpet, wherever the colonisers went. The wolves were given poisoned meat, the Indigenous blankets impregnated with smallpox. Roads in Kansas were paved with wolf bones. In the 1843 Trapper’s Guide, Sewell Newhouse described how his eponymous wolf traps were part of a trinity of tools, along with the axe and plough, that were ‘pushing back barbaric solitude’ to make way for ‘the wheatfield, the library and the piano’. Such logic pertained everywhere. As late as 1963 Italian environmentalist Alessandro Ghigi wrote that the continued presence of wolves in the south of Italy was indicative of ‘a backward economy and civilization’. It is astonishing to think that in the mid-twentieth century, before advances in technology and field studies, that little more was understood about this shyest of animals than when the medieval bestiaries were written. Had we pushed them to extinction, we might never have known.

In the pursuit of civilisation, wolves were fed glass, strung up, set on fire and ripped apart by horses. Pups were gassed in their dens; cyanide bombs were deployed to eject sodium cyanide into their mouths. A dog in heat was tethered to a stake, and when a passing wolf was

caught in the copulatory tie, men set on it and beat it to death. Estimates for the number of wolves killed in North America range between one million and two. ‘Such behavior amazed Native Americans,’ wrote wildlife journalist Ted Williams. ‘Their explanation for it was that, among palefaces, it was a manifestation of insanity.’ Whatever it was, it was effective. Whosoever believes that humanity cannot pull together to effect great change would do well to remember this. By the end of the Second World War, wolves were entirely gone from Central Europe and Scandinavia. There were two small groups left in the Apennines, a few in Iberia and some larger remnants in Eastern Europe. In the United States there were several packs in Minnesota and, but for Alaska, that was it. Outside of the empty expanses of Canada or Russia and some other, isolated pockets, you would struggle to find a wolf anywhere at all. An animal that had dominated almost every habitat of the Northern Hemisphere for three-quarters of a million years was hovering on the brink of extinction. But this was not to be their final act. Both the wolves and their executioners were to be granted a reprieve. Since the wolf’s nadir in Europe, in 1965, their population has increased 1,800 per cent. What had once seemed an extinction turns out to be a hiatus. Their place kept warm, the land holding its breath, until they slipped back in. In 2016 there were 17,000 wolves in Europe, and today the best estimate for the number on the continent (excluding Belarus and European Russia, for which there is no

available data) is north of 21,500, putting them as a species of ‘Least Concern’. Europe’s other large carnivores are on similar, although not quite such stratospheric, trajectories. There are more wolves in Europe than there are in the US , more bears in Europe than lions in Africa. We’re not talking about cockroaches or rats here, feral animals thriving on humanity’s spread. These are apex predators, the symbolic embodiment of wilderness. And nowhere in Europe have wolves been reintroduced. They have done this entirely on their own.

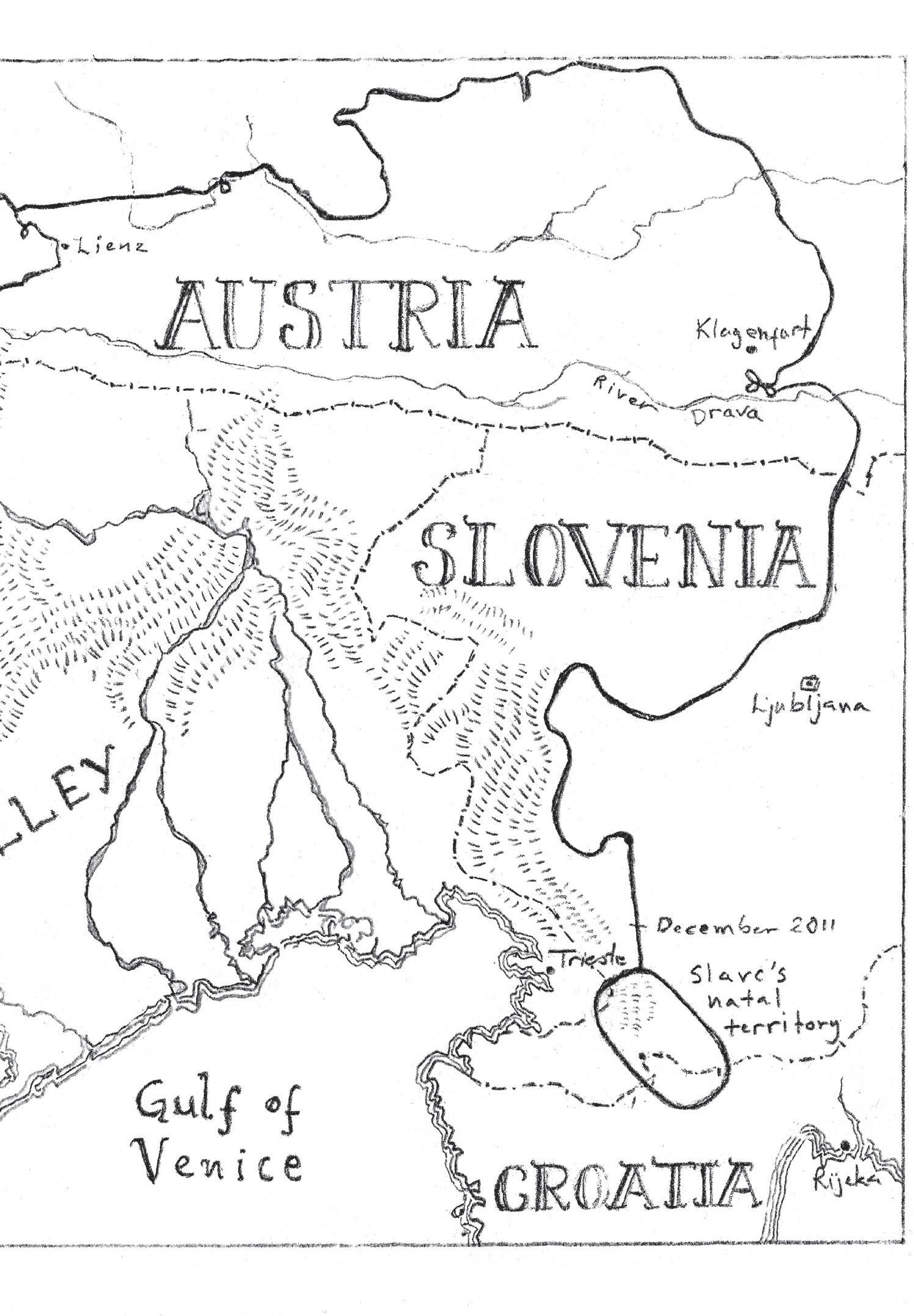

Slavc, the wolf that I have come to speak to Hubert Potočnik about, is one of the pioneers. In late 2011, at just nineteen months, he quit his natal territory in the south of Slovenia and began a journey of several thousand kilometres. North across Slovenia, west through Austria, south-west into the heart of the Italian Alps. He swam rivers and crossed six-lane highways. He grazed the capitals of Slovenia and Carinthia, Austria’s southernmost state. He climbed to passes in excess of 2,500 metres in the middle of a particularly harsh winter. It is impossible to overstate quite how ambitious this was. He was forging a path back into a hostile Europe that had not known his kind for generations. There could have been anything out there, or nothing. I think of those Celtic monks casting off in their coracles, navigating over the horizon by nothing more than faith. A ship sailing off the world’s edge.

Wolves are capable of greater distances than any other terrestrial animal on the planet. A male in Mongolia has

the record – 7,245 kilometres in a single year, the same distance as from London to Delhi. But what made Slavc’s journey so notable was that in the months prior to his departure, and knowing nothing of what he would go on to do, Hubert had collared him with a GPS tracker as part of his ongoing research into wolf behaviour. The map that Slavc produced once he left home – one waypoint every 190 minutes for 100 days, arcing in a rough horseshoe through the mountains of Eastern Europe – gave Hubert and his team a chance to observe a wolf travelling through the heart of the continent, through densely populated human landscapes, with total precision. Each new data point underscored the wolf’s tenacity and endurance, the desire for life to thrive.

And then in Italy, in the mountains of Lessinia, north of Verona, Slavc ran into a female wolf on a walkabout of her own. How they found each other is one of the reasons that animals will forever be an enigma. The female wolf, swiftly and inevitably, was christened Juliet by the local press, after one half of Verona’s most famous couple. When they bred, they became the first pack in Italy, outside of the Apennines and the border region to the west, for more than a hundred years. A decade on and there are at least seventeen packs back in those mountains.

To defy centuries of persecution, to find one another in the sheer immensity of the Alps, to repopulate the lands that they were banished from – for even the most rational of scientists, it is hard not to see this as a love