HELEN M C CLOY WITH A

M C ALLISTER

the mermaid collection

M C ALLISTER

the mermaid collection

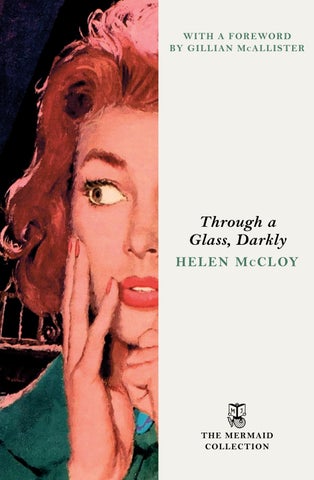

First published in 1950, Helen McCloy’s Through a Glass, Darkly was her eighth Dr Basil Willing novel. It is being reissued as one of Penguin Michael Joseph’s Mermaids series – a collection of unjustly neglected works of popular mid-to-late-twentieth-century literature. Each Mermaid is introduced by a modern writer, reflecting on the author and book’s importance to the world in which it was published and its continued relevance today.

This Mermaid is introduced by Gillian McAllister, the crime, mystery and thriller writer of the million-copy-selling Wrong Place, Wrong Time.

To hear more about The Mermaid Collection, visit www.penguin.co.uk/TheMermaidCollection

PENGUIN BOOK S

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published by Random House 1950 This edition published by Penguin Books 2025 001

Copyright © Pollinger Ltd as Literary Executor of the Estate of Helen McCloy, 1950 Foreword copyright © Gillian McAllister, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

This book is a child of 1950 and may contain language or depictions that some readers might find outdated today. Our general approach is to leave the book as the author wrote it. We encourage readers to consider the work critically and in its historical and social context. In this case we have edited, exceptionally and minimally, the most highly offensive language. Together with the Estate of Helen McCloy, we believe this change preserves the essence and integrity of the original work

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception

Set in 10.5/14.25 pt Sabon LT Std Typeset by Six Red Marbles UK, Thetford, Norfolk Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn : 978– 1– 405– 98417– 1

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

For Chloe

‘Little green shoot that came up in the Spring’

Through a glass , darkly is perhaps Helen McCloy’s seminal work of gothic fiction. Part detective investigation, part psychological thriller, the concept revolves around a young teacher, Faustina Crayle, who in the novel’s early chapters appears, on multiple occasions and with multiple witnesses, to be able to be in two places at once. The thrust of the novel is concerned with the hows and whys of this and, later, with unravelling a Golden Age-style murder mystery connected to it. I like to try to guess twists, and I did not guess the reveal, which ties together details the reader would have deemed irrelevant before threading them into a Poirot-esque denouement. This genre-blending cosy crime feels absolutely relevant still in 2025, for a whole host of reasons.

Brereton Girls’ School, the novel’s main setting, is of a type very often used today, much lauded on social media and with a whole host of connected tropes – set in autumn, mysterious goings-on, school hallways at night, lamplit driveways, secret visitors . . . I hugely enjoy the look into life as a teacher at one such institution, especially the fast-paced plot that begins on

page one: in the very first scene, Faustina is being dismissed for her unearthly double’s appearances.

The novel’s set-up might today sit at the juncture between horror, paranormal, and what we now call a psychological thriller, but which of course has long existed. Much like in the modern-day works of Lucy Foley, C. J. Tudor and Mark Edwards, there’s an is-there-or-isn’t-there element to the trope of the Doppelgänger in this book, with its clear allusions to Doctor Faustus by Christopher Marlowe. Is it supernatural, in line with its hints to the paranormal, the towers of the dark academic setting, the noises heard in the night? Or is this a straight psychological thriller, much like those written by Sophie Hannah, where the premise may seem somewhat supernatural, but the explanation is always grounded in reality?

From this intriguing opening, McCloy begins with an omniscient narrator who does not enter the heads of the characters for some time; we observe alongside the narrator the dismissal of Faustina, then move to witness various other characters’ experiences of her, pulling together the intriguing accounts of her suspicious colleagues, the frightened teenage schoolgirls, and finally a psychiatrist, who is Basil Willing, the detective-like character who begins to move the narrative forwards with his sleuthing.

The choice of a non-detective detective, employed by many psychological thriller writers operating today, draws the narrative away from police procedure and opens it up to something far more interesting: Basil Willing interviews a lawyer who may have acted for Faustina, considers the history of the Doppelgänger in folklore and its context in the emerging psychiatry of the day, and finally, as a reader, we enter his thoughts in close third-person at about the halfway point, when a body is discovered. Here, the plot goes off like

a rocket, pulling in various suspects and theories from school pupils to hallucinations to ghosts.

The reveal, when it comes, is a satisfyingly linear solution. The reader may not know it, but the various turns the plot takes are leading towards a denouement by way of attrition: everything we are told becomes relevant. A classic Golden-Age ending comes in the form of a speech delivered by Basil Willing, where multiple clues are held up in different ways to form a coalescent whole. To reveal more would spoil the ending, but I loved it.

I also enjoy the various insights into working life in postwar America. As we head into Basil’s narration, we follow him around New York, out from the grounds of Brereton and into the city, with all its newspaper stands and high-rise offices. The fashion, also, is given a keen eye: savour the gorgeous references to colours and fabrics.

As gripping as anything written today, Through a Glass, Darkly is a masterclass in atmosphere, misdirects, and interesting revelations that cover all sorts – parentage, the myth of the double, the afterlife – all presented eruditely through Basil’s narration. I hope you enjoy it.

NB A small word on some of the language used in this novel: being a product of history, there are words and phrases that readers today may find offensive, and I join you there; there were one or two extremely jarring moments for me. Only small amendments have been made because of a lack of desire to pretend these things did not happen, or to risk washing the past of its ugliness, but please know I am with you on feeling a little unsettled at times, and I use this motivation to better myself now as our world hopefully becomes more inclusive.

Gillian McAllister, 2025

You have the face that suits a woman

For her soul’s screen, The sort of beauty that’s called human In Hell, Faustine.

Mrs Lightfoot was standing by the bay window. ‘Sit down, Miss Crayle. I’m afraid I have bad news.’

Faustina’s mouth held its usual mild expression, but a look of wariness flashed into her eyes. Only for a moment. Then the eyelids dropped. But that moment was disconcerting – as if a tramp had looked suddenly from the upper windows of a house apparently empty and secure against invasion.

‘Yes, Mrs Lightfoot?’ Faustina’s voice was low-pitched, clear – the cultivated speech expected of all teachers at Brereton. She was tall for her sex and slender to the point of fragility, with delicate wrists and ankles, narrow hands and feet. Everything about her suggested candour and gentleness – the long, oval face, sallow and earnest; the blurred, blue eyes, studious, a little near-sighted; the unadorned hair, a thistledown halo of pale tan that stirred softly with each movement of her head. She seemed quite composed now as she crossed the study to an armchair.

Mrs Lightfoot’s composure matched Faustina’s. Long ago she had learned to suppress the outward signs of embarrassment. At the moment her plump face was stolid with something of the look of Queen Victoria about the petulant thrust of the lower lip and the light, round eyes protruding between white lashes. In dress she affected the Quaker colour – the traditional ‘drab’ that dressmakers called ‘taupe’ in the thirties and ‘eel-grey’ in the forties. She wore it in rough tweed or rich velvet, heavy silk or filmy voile according to season and occasion, combining it every evening with her mother’s good pearls and old lace. Even her winter coat was moleskin – the one fur with that same blend of dove-grey and plum-brown. This consistent preference for such a demure colour gave her an air of restraint that never failed to impress the parents of her pupils.

Faustina went on: ‘I’m not expecting bad news.’ A deprecating smile touched her lips. ‘I have no immediate family, you know.’

‘It’s nothing of that sort,’ Mrs Lightfoot answered. ‘To put it bluntly, Miss Crayle, I must ask you to leave Brereton. With six months’ pay, of course. Your contract provides for that. But you will leave at once. Tomorrow, at the latest.’

Faustina’s bloodless lips parted. ‘In mid-term? Mrs Lightfoot, that’s – unheard of!’

‘I’m sorry. But you will have to go.’

‘Why?’

‘I cannot tell you.’ Mrs Lightfoot sat down at her desk – rosewood, made over from a Colonial spinet. Beside the mauve blotter were copper ornaments and a bowl of oxblood porcelain filled with dark, sweet, English violets.

‘And I thought everything was going so beautifully!’ Faustina’s voice caught and broke. ‘Is it something I’ve done?’

‘It’s nothing for which you’re directly responsible.’ Mrs Lightfoot lifted her eyes again – colourless eyes bright as glass. Like glass, they seemed to shine by reflection, as if there were no beam of living light within. ‘Shall we say that you do not quite blend with the essential spirit of Brereton?’

‘I’m afraid I must ask you to be more specific,’ ventured Faustina. ‘There must be something definite or you wouldn’t ask me to leave in mid-term. Has it something to do with my character? Or my capability as a teacher?’

‘Neither has been questioned. It’s simply that – well, you do not fit into the Brereton pattern. You know how certain colours clash? A tomato-red with a wine-red? It’s like that, Miss Crayle. You don’t belong here. That must not discourage you. In another sort of school, you may yet prove useful and happy. But this is not the place for you.’

‘How can you tell when I’ve only been here five weeks?’

‘Emotional conflicts develop rapidly in the hothouse atmosphere of a girls’ school.’ Opposition always lent a sharper edge to Mrs Lightfoot’s voice and this was unexpected opposition, from one who had always seemed timid and submissive. ‘The thing is so subtle, I can hardly put it into words. But I must ask you to leave – for the good of the school.’

Faustina was on her feet, racked and shaken with the futile anger of the powerless. ‘Do you realize how this will affect my whole future? People will think that I’ve done something horrible! That I’m a kleptomaniac or worse!’

‘Really, Miss Crayle. Those are subjects we do not discuss at Brereton.’

‘They will be discussed at Brereton – if you ask a teacher to leave in the middle of the fall term without telling her why! Only a few days ago you said my classroom was “most satisfactory”. Those were your very words. And now . . . Someone

must be telling lies about me. Who is it? What did she say? I have a right to know if it’s going to cost me my job!’

Something came into Mrs Lightfoot’s eyes that might have been compassion. ‘I am indeed sorry for you, Miss Crayle, but the one thing I cannot give you is an explanation. I’m afraid I haven’t thought about this thing from your point of view – until now . . . You see, Brereton means a great deal to me. When I took the school over from Mrs Brereton, after her death, it was dying, too. I breathed life into it. Now our girls come from every state in the Union, even from Europe since the war. We are not just another silly finishing school. We have a tradition of scholarship. It has been said that cultivation is what you remember when you have forgotten your education. Brereton graduates remember more than girls from other schools. Two Brereton girls who meet as strangers can usually recognize each other by the Brereton way of thinking and speaking. Since my husband’s death, this school has taken his place in my life. I am not ordinarily a ruthless person but when I am faced with the possibility of your ruining Brereton, I can be completely ruthless.’

‘Ruining Brereton?’ repeated Faustina, wanly. ‘How could I possibly ruin Brereton?’

‘Let us say, by the atmosphere you create.’

‘I don’t know what you mean.’

Mrs Lightfoot’s glance strayed to the open window. Ivy grew outside, freckling the broad sill with patches of leafy shadow. Beyond, a late sun washed the faded grass of autumn with thin, clear light. The afternoon of the day and the afternoon of the year seemed to meet in mutual farewell to warmth and brightness.

Mrs Lightfoot drew a deep breath. ‘Miss Crayle, are you quite sure you can’t – guess?’

There was a moment’s pause. Then Faustina rallied. ‘Of course I’m sure. Won’t you please tell me?’

‘I did not intend to tell you as much as I have. I shall say nothing more.’

Faustina recognized the note of finality. She went on in a slow, defeated voice, like an old woman. ‘I don’t suppose I can get another teaching job, so late in the school year. But if I should get a post next year – can I refer a prospective employer to you? Would you be willing to tell the principal of some other school that I’m a competent art teacher? That it really wasn’t my fault I left Brereton so abruptly?’

Mrs Lightfoot’s gaze became cold and steady, the gaze of a surgeon or an executioner. ‘I’m sorry, but I cannot possibly recommend you as a teacher to anyone else.’

Everything that was childish in Faustina came to the surface. Her pale tan lashes blinked away tears. Her vulnerable mouth trembled. But she made no further protest.

‘Tomorrow is Tuesday,’ said Mrs Lightfoot briskly. ‘You have only one class in the morning. That should give you time to pack. In the afternoon, I believe you are meeting the Greek Play Committee at four o’clock. If you leave immediately afterward you may catch the six twenty-five to New York. At that hour, your departure will attract little attention. The girls will be dressing for dinner. Next morning, in Assembly, I shall simply announce that you have gone. And that circumstances make it impossible for you to return – greatly to my regret. There should be hardly any talk. That will be best for the school and for you.’

‘I understand.’ Half blinded by tears, Faustina stumbled toward the door.

Outside, in the wide hall, a shaft of sunlight slanted down from a stair window. Two little girls of fourteen were coming

down the stairs – Meg Vining and Beth Chase. The masculine severity of the Brereton uniform merely heightened Meg’s feminine prettiness – pink-and-white skin, silvergilt curls, eyes misty bright as star sapphires. But the same uniform brought out all that was plain in Beth – cropped, mouse-brown hair; sharp, white face; a comically capricious spattering of freckles.

At sight of Faustina, two little faces became bland as milk, while two light voices fluted in chorus: ‘Good afternoon, Miss Crayle!’

Faustina nodded mutely, as if she couldn’t trust her voice. Two pairs of eyes slid sideways, following her progress up the stair to the landing. Eyes wide, but not innocent. Rather, curious and suspicious.

Faustina hurried. She reached the top, panting. There she paused to listen. Up the stairwell came a tiny giggle, treble as the hysteria of imps or mice.

Faustina moved away from the sound, almost running along the upper hall. A door on her right opened. A maid, in cap and apron, came out and turned to look through a window at the end of the hall. Her sandy hair caught the last light of the sun with a gleam like tarnished brass.

Faustina managed to compose quivering lips. ‘Arlene, I’d like to speak to you.’

Arlene jerked violently and swung round, startled and hostile. ‘Not now, miss! I have my work to do!’ ‘Oh . . . Very well. Later.’

As Faustina passed, Arlene shrank back, flattening herself against the wall.

The two little girls had looked after Faustina slyly, with mixed feelings. But this lumpy face was stamped with one master emotion – terror.

What adders came to shed their coats, What coiled, obscene, Small serpents with soft, stretching throats

Caressed Faustine?

Faustina entered the room Arlene had just left. There was a white fur rug on the caramel floor. White curtains framed the windows. The chest of drawers was painted daffodil yellow. On the white mantelpiece stood brass candlesticks with crystal pendants and candles of aromatic green wax made from bayberries. Wing chair and window seat were covered with cream chintz sprigged with violet flowers and green leaves. The colours were gay as a spring morning, but – the bed was unmade, the scrapbasket unemptied, the ashtray choked with ashes and cigarette-butts.

Faustina closed the door and crossed the room to a window seat where a book lay open. She turned the pages in frantic haste. A tap fell on the door. She closed the book and thrust it down behind a cushion, straightening the cushion so there was no sign that it had been disturbed.

‘Come in!’

The girl on the threshold looked as if she had stepped from

an illuminated page of Kufic script, where Persian ladies, dead two thousand years, can still be seen riding mares as dark-eyed, white-skinned, fleet, and slender as themselves. She could have worn their rose-and-gold brocade with grace. But the American climate and the twentieth century had put her into a trim grey-flannel skirt and a pine-green sweater.

‘Faustina, those Greek costumes . . .’ She stopped. ‘What’s wrong?’

‘Please come in and sit down,’ said Faustina. ‘There’s something I want to ask you.’

The other girl obeyed silently, choosing the window seat instead of the armchair.

‘Cigarette?’

‘Thanks.’

Slowly, precisely, Faustina put the cigarette-box back on the table. ‘Gisela, what is the matter with me?’

Gisela answered cautiously. ‘What do you mean?’

‘You know perfectly well what I mean!’ Faustina spoke in a dry, cracked voice. ‘You must have heard gossip about me. What are they saying?’

Long black lashes are as convenient as a fan for screening the eyes. When Gisela lifted hers again her gaze was noncommittal. One hand made a little gesture toward the cushion beside her, trailing cigarette-smoke.

‘Sit down and be comfortable, Faustina. You don’t really suppose I have a chance to hear gossip, do you? I’m still a foreigner and I came here as a refugee. No one ever trusts foreigners – especially refugees. Too many were maladjusted and ungrateful. I have no intimate friends here. The school tolerates me because my German is grammatical and my Viennese accent is more pleasing to Americans than the speech of Berliners. But my name, Gisela von Hohenems, has

unpleasant connotations so soon after the war. So . . .’ she shrugged, ‘I spend very little time over teacups and cocktail glasses.’

‘You’re evading my question.’ Faustina sat down without relaxing. ‘Let me put it more directly: have you heard any gossip about me?’

The pretty line of Gisela’s mouth was distorted by that expression our friends call ‘character’ and our enemies, ‘stubbornness’. She answered curtly: ‘No.’

Faustina sighed. ‘I wish you had!’

‘Why? You want people to gossip about you?’

‘No. But since they are gossiping, I wish they had gossiped with you. For you are the only person I can ask about it. The only person who might tell me what is being said and who is saying it. The only real friend I’ve made here.’ She flushed with sudden shyness. ‘I may call you my friend?’

‘Of course. I am your friend and I hope you’re mine. But I’m still at sea about this. What makes you think there is gossip about you?’

Carefully Faustina crushed her cigarette in the ashtray. ‘I’ve been – fired. Just like that.’

Gisela was taken aback. ‘But – why?’

‘I don’t know. Mrs Lightfoot wouldn’t explain. Unless you call a lot of woolly platitudes about my not fitting into the Brereton pattern an explanation. I’m leaving tomorrow.’ Faustina choked on the last word.

Gisela leaned forward to touch her hand. That was a mistake. Faustina’s features twisted. Tears sprang into her eyes as if a cruel, invisible hand were squeezing them out of her eyeballs. ‘That’s not the worst.’

‘What is the worst?’

‘Something is going on all around me.’ Words tumbled