GODFREY

GODFREY

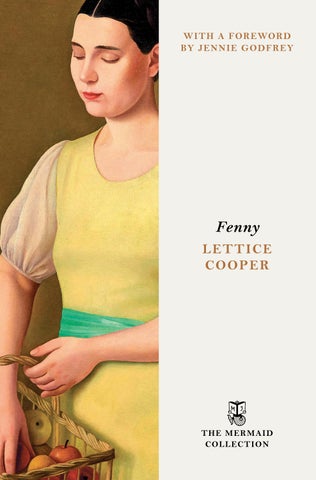

First published in 1953, Lettice Cooper’s Fenny celebrates her love of Italy. It is being reissued as one of Penguin Michael Joseph’s Mermaids series – a collection of unjustly neglected works of popular mid-to-latetwentieth-century literature. Each Mermaid is introduced by a modern writer, reflecting on the author and book’s importance to the world in which it was published and its continued relevance today.

This Mermaid is introduced by Jennie Godfrey, author of the Sunday Times number one bestseller The List of Suspicious Things.

To hear more about The Mermaid Collection, visit www.penguin.co.uk/TheMermaidCollection

PENGUIN BOOK S

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published by Victor Gollancz Ltd 1953

This edition published by Penguin Books 2025 001

Copyright © Lettice Cooper, 1953

Foreword copyright © Jennie Godfrey, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

This book is a child of 1953 and may contain language or depictions that some readers might find outdated today. Our general approach is to leave the book as the author wrote it. We encourage readers to consider the work critically and in its historical and social context

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception

Set in 10.5/14.25pt Sabon LT Std

Typeset by Six Red Marbles UK , Thetford, Norfolk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn: 978– 1– 405– 98415– 7

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

Dedicated to mary christine brettell ‘Telly’

There are so many things to love about Lettice Cooper’s Fenny, I almost don’t know where to start. Not least because reading this wonderful novel sent me down the rabbit hole of discovering everything I could about the author Lettice Cooper. This now means I have discovered a novelist who, though less well known than some of her contemporaries, played a significant role in the literary world of the time.

Like me, Lettice (1897–1994) was Yorkshire born and raised, and the influence of the county seeps into her writing both implicitly and explicitly (more on which below). She was prolific, and her twenty novels capture the lives of ordinary people in ways that make them – and their stories – come alive. This is something I aspire to do in my own work, and something which is particularly finely done in Fenny. As well as writing novels (both for adults and children) she also wrote for the Yorkshire Post and was a vital participant in the writing and artistic communities. She was a founding member of the Writers’ Action Group and was a vocal

campaigner for Public Lending Right: a legal right that means authors get paid when their books are borrowed from the library, which remains an important part of author income today. She was described in her obituary by friends as having ‘radical opinions’, as well as ‘optimism and a zest for life’. I like to imagine that we would have been friends had I been lucky enough to meet her.

Fenny was first published in 1953 and was hailed as one of Cooper’s best novels. I can see why. It is the story of Ellen Fenwick (nicknamed ‘Fenny’), a Yorkshire schoolteacher who we meet on her way to Italy where she is about to start work as a governess to a young girl, Juliet, for the summer. We then dip in and out of episodes of Ellen’s life from 1933 to 1949 as she navigates life in Italy, romantic potential and making a living for herself, all against the backdrop of the threat, then aftermath, of World War Two (Cooper makes the choice to leave the war years themselves out of sight of the reader).

Going into Fenny, I was prepared to make allowances for the time in style and content, but was surprised by its contemporary tone and subject matter. I found myself feeling a deep empathy for Ellen, despite almost a century’s difference in age and experience. From the woman herself to the challenges she faces in romantic, platonic and familial relationships, the novel has an unexpected freshness and relevance.

It is set almost entirely in Italy, but we see and feel the influence of Yorkshire on Ellen’s life and personality, from her memories of her past as a schoolteacher – which ‘belonged to life in the Northern industrial town where beauty was incidental and happiness a by-product’ – to, perhaps more interestingly, her reflections on the tension between her own rather practical temperament versus that of the often more overtly passionate people she meets. These include

Madeleine, Juliet’s highly strung mother. Following a particularly dramatic episode of Madeleine’s, Ellen remarks: ‘it had been implicit in her upbringing that action was safe, but feeling was dangerous, and she looked at Madeleine as someone who in the night had nearly fallen off a tight-rope, but had managed to scramble back.’

Another thing I love about the book is that we don’t only see Fenny in the first flush of youth. The novel is split into four parts and so we are given the opportunity to grow with Ellen. I was particularly struck by the final section, maybe because of my own age, but Fenny’s changing looks, body and health – the reference to menopause in a book of the time feels particularly radical – including her regret at not having children, plus her ongoing relationship to work and money, felt wholly relatable. The things that preoccupy Fenny are the things that preoccupy me.

The novel is full of psychological insight too. At one point Fenny observes: ‘I think there is a very deep pattern in our lives, often a repeating pattern so deep that we only see it occasionally, and what we do or what happens to us often seems like pure chance, but it’s all very closely knit. It’s just that we don’t see the pattern.’ According to her friend Francis King, Cooper herself went through some years of psychoanalysis which might go some way towards explaining this, but that understanding of the human mind, and the way people work, feels as though it could be written now. By the end of the novel, Ellen is surrounded by a nontraditional family of her own making, consisting of Juliet, the now grown-up young woman who she was governess for at the start of the novel; Shand, a young man who she also met during that time; and Dino, a boy whose mother tragically died during the war, and who Ellen nursed. In modern

parlance we might call it a chosen family, but it is a family nonetheless, and I love that Fenny led such a full life without being married or having biological children (at a time when this would have been less usual or accepted).

Fenny’s life experience is presented in all its complexity, without pity, and we get to see its inner and outer richness, making the reader experience one of great pleasure. I cannot recommend it enough.

Jennie Godfrey, 2025

Ellen Fenwick first came to the Villa Meridiana in April. Long before the train ran into the station at Florence she had been sitting on the edge of the seat, a starter poised for a race, handbag, overcoat and umbrella disposed on one arm, so as to leave the other free for her luggage. She recognized that she had not the same grip on the wagon-lit attendant as the companion who had shared her sleeper as far as Pisa. This woman, the wife of an hotel-keeper in Lucca, with a daughter married in England, had chattered to her in bad English ever since they found themselves in the same compartment at Calais, but she was a hardened traveller, who with one wave of her hand in its tight black glove subdued the unknown terrors of the journey and left Ellen free for enjoyment. Replying ‘Yes!’ ‘Really?’ ‘Do you?’, ‘That must be nice for your daughter!’, she sucked into her eyes the mountains of Northern Italy, the pink farms, and the interrupted glimpses of the sea, appearing between the rattling tunnels.

Now it was dark, and she was alone. To watch the Signora,

who had been her family in space for twenty-four hours, stump away under the platform lights of Pisa between her husband and son who had come to meet her, was for Ellen the final parting from home.

As soon as the train left Pisa she opened the door of the cabinet de toilette and looked at herself in the mirror, partly to make sure that she was tidy, partly to reaffirm her identity. The mirror showed her an image which to eyes whose horizon was already widening appeared slightly comic. She had not cut her hair short, in the fashion, but wore it in two thick plaits, coiled over her ears. The new felt hat, which in the shop had seemed to settle harmoniously on the coils, now proved only to be comfortable if she allowed it to slip forward over her nose. She pushed it back, relentlessly driving the hairpins into her ears. The lifted brim exposed a candid forehead, delicate eyebrows and grey eyes, smudged beneath with fatigue and strain. The cheeks were too thin for the bone-structure of nose and chin. It was the kind of face that suggests a daughter taking after her father. Ellen, when she looked at it again, always hoped that it would have improved since her last inspection, but did not often think that it had.

She put a finger under one hairpin and tried to relieve the pressure, but as soon as she removed the finger the hat drove the hairpin back. Well, she must suffer so as to arrive looking like a suitable governess, and perhaps at the villa she need not wear a hat. Mrs Rivers had written that they were five miles out of Florence. She hoped that Miss Fenwick liked a country life.

Ellen had made an imaginary picture of Mrs Rivers, seeing her, the mother with the little girl, an authoritative figure, much older and wiser than herself, invulnerable, the mother seen by the little girl. Ever since Lady Gressingham had told

her that Madeleine Rivers was Rose Danby’s daughter, the image had crystallized into something like Rose Danby’s stage presence. This had been for Ellen the thing that clinched her decision to take the job for the summer. She had looked blank with astonishment when Lady Gressingham, telling her about Madeleine Rivers, had added, ‘Poor girl! It’s not so easy, you know,’ the old woman remarked, ‘to be a famous person’s child.’ But, Ellen thought, so interesting! She had always been stage-struck. The treats that she had enjoyed most from her first pantomime had been visits to the theatre. Rose Danby, whom she had seen whenever she had an opportunity, had stimulated her sense of life as it really was but was so seldom allowed to be. This made the prospect of six months in a villa in Italy as governess to Rose Danby’s granddaughter so dazzling and so unlike anything that had ever happened to her as to outweigh the inevitable terrors of one desperately homebound for seven years.

Besides, if she did not make a break now, when would she? ‘Are you wise,’ her mother’s friends said, ‘to throw up a permanent position for a temporary one? Is it a good thing to let your place at the High School be filled, even for a term? Suppose they decide to keep on your substitute?’ To her mother’s friends, Ellen was always a girl doing her best, but not to be expected to do it well. To her headmistress Ellen’s sudden desire to go abroad for a summer after her mother’s death appeared a mild form of illness, the result of shock, which she treated with the sane and liberal understanding that Ellen had always admired and suddenly found intolerable. Only Alice, who would miss her most, said ‘Go!’ – but Alice was fond of her.

Well, Ellen thought, suppose they don’t want me back? Do I really want to stay here until the Board present me with

a cheque and a set of coffee-cups? Until I am the only one on the staff who remembers the old girls when they come to their daughters’ prize-giving? Is Ainley the world? Here, in this swaying train between two unknown foreign stations, at least it was not. The excitement that had been working in her all through the journey made her courage rise. Even if, by some mischance, nobody met her at the station – a possibility that had haunted her for several days – she had money, she had an Italian phrase-book; she was not a child! With resolution she shut the door of the cabinet on the face in the mirror that still betrayed some qualms, and collected her things.

She thought at first that there was no one to meet her. She stood on the platform by her suit-cases, and the mob of chattering, gesticulating Italians swept round and past her as if she were a stone dividing a stream. As the platform began to clear she saw a man unmistakably English hurrying towards her. In that second of impact before the whole stranger is refracted through speech, her impression of Charles Rivers, beyond the obvious facts that he was of medium height and broadly built, sunburnt and dressed in casual clothes, was that he was exasperated. At once she felt in some way at fault; perhaps, after all, her train was late, or she should have gone down to the barrier. As soon as he smiled and spoke to her cordially, the impression receded.

‘Miss Fenwick? I thought you must be. I’m Charles Rivers. My wife was so very sorry she couldn’t come down to meet you. Some people turned up unexpectedly for a drink and stayed late. I do hope you’ve had a good journey? Are these all your things?’

A porter appeared and swept her suit-cases on to a barrow. Mr Rivers took her coat over his arm and said, ‘Got your

ticket?’ With relief she felt herself out of her own charge and in capable hands.

It was so much more of a relief than she would have been willing to admit that she felt dazed, and, as if half under an anaesthetic, heard her own voice replying that she had slept pretty well in the wagon-lit, that her companion had been an Italian woman who got out at Pisa, that she had never been to Italy before, only once some years ago for a holiday to Belgium, and once to Paris for a week.

‘I think you’ll like it here,’ Mr Rivers said as he shut her into the car and got in beside her.

The strange city through which they drove was the scenery of a dream. She saw tall, flat-fronted houses with shuttered windows, stone façades lit by street lamps. Mr Rivers said, ‘The Duomo – the Cathedral,’ and she peered at a mass of building, improbably striped black and white – not her idea of cathedrals. It was only when she caught a glimpse of the arches of a bridge, of lights reflected in flowing water, and her companion said, ‘The Arno,’ that expectation burst in her like a bubble; what had been names and distance on the map suddenly assumed substance. She thought, This is Florence. I’m here! and longed for Alice rather than for a stranger with whom she was not yet ready to share her excitement.

As they emerged from the main streets and drove along the Lung’arno between the river and the houses, he began to talk to her about Juliet.

‘I think you’ll find her nice to teach. She’s very bright – at least, we think so. I suppose she may be just like any other kid of eight, really.’

At once Mr Rivers slipped into focus. He was no longer a stranger, but a parent. Strangers might be formidable; but parents, with their assumed deprecation, their barely concealed

conviction that their children were never ordinary, were not strangers: they were an annexe to what had been her life for seven years.

‘I’m very much looking forward to seeing Juliet. Will she be up?’

‘No, we thought you’d like to have your first evening in peace. Besides, it’s rather late for her. She’s been ill, you know. I expect Madeleine told you. She had a very bad go of measles and middle-ear trouble in February, and she’s still a bit thin and tearful, not quite like herself. So we thought she should have a summer out of London, somewhere where we could be sure of the sun. Madeleine needed a holiday, too, after nursing her. And then Helena Gressingham offered to lend us this villa; much too good an offer to refuse, as you’ll see tomorrow.’

‘I’ve seen pictures of it.’

She could see them now hanging on the faded green distemper of the schoolroom at Hawton Towers. To remember them brought back the smells of blackboard chalk and toast made by the fire. Those pictures had seemed to her so beautiful, the sky so blue, the big white house with its square, red-roofed tower a house in a fairy-tale, unlike any house she knew in the Northern county of grey stone. They had certainly played their part with Rose Danby in deciding her to come to the villa.

‘Oh, those dreadful water-colours of Violet’s!’

‘Are they dreadful?’

He laughed.

‘Well, didn’t you think so?’

She could not explain that she had never seen them out of her own imagined context. She only said lamely:

‘They were in the schoolroom at Hawton Towers.’

‘Yes, I’m sure they were!’ He added, with a faint inflexion of surprise, ‘You know the Gressinghams quite well, don’t you?’

‘My father was the doctor for a big, scattered practice that included Hawton. I did lessons at the Towers with Angela Gressingham for two years before she went away to school. Since my father died and we moved into Ainley and Angela got married, I haven’t been there so often, but I go over whenever Angela comes up to stay. Lady Gressingham has always been very kind to me.’ With an effort she added formally, ‘I was most grateful to her for recommending me for this post.’

‘She told us that we were very lucky to get you, and I’m sure we are.’

They had crossed the river by a bridge, and seemed to be climbing steadily, a narrow road between the high walls of gardens and houses. Once they were crowded – Ellen thought that they would be crushed – into the wall by a car tearing down towards them at breakneck speed. She sagged now with fatigue, her head felt too heavy for her neck and her eyelids dropped. The journey had become a journey outside place and time. She could not remember the beginning nor imagine the end. It merged with a journey out of childhood; she was back again in the big car that was bringing her home from the Towers after Angela’s Christmas Party. Nearly lost in her mother’s old fur coat that came down to her ankles, she hugged on her knee beneath it her present from the Christmas tree. They drove over a patch of moorland, and a blizzard swept across, plastering the window of the car with halffrozen snow. She saw the windscreen wiper climbing heavily under a wedge of snow, and heard old Carter grumbling to himself behind the wheel. Her feet in their bronze sandals were numb with cold, her nose and ears felt icy. She began

to be frightened and to feel that she would never get home: the car would be stuck in the snow up here on the moors, and only after the thaw would her dead body and Carter’s be found. Then, almost before she realized it, they were off the moor. The wheels were crackling on the ice in the village street; she saw the shape of the church thickened by snow; the Vicarage buried in snow-bushes; their own house with the curtains drawn back to show the lights, and as the car drew up, the door opened and her mother stood in the lighted doorway. Now, as she half woke, half dozed again, the two journeys were still confused, and she did not know if she were going towards an old or a new homecoming.

Mr Rivers’ voice saying, ‘Well, here we are,’ jerked her into the present. She stumbled out of the car, and stood on a sweep of gravel, feeling the air cool against her cheeks. In the pale façade that rose above them an archway sprang into light. Looking through, Ellen saw what seemed to her like the quadrangle of a college with round pillars, a vaulted cloister and pale walls. Servants – a man in a white coat, a girl with swinging print skirts – came to take the luggage.

Mr Rivers said something to them in Italian of which she understood only, ‘The Signorina Fenwick from England.’ To her, ‘This is Ofelia. This is Gastone.’ Their welcoming smiles made her feel as if they were really glad to see her. ‘They’ll bring all your things.’

She walked beside him across the courtyard, roofless except for the cloister running down one side. Before they reached the door in the opposite wall it opened. A young woman, pretty as a flowering tree, stood in the doorway, holding out both hands in a graceful gesture of welcome.

‘Here you are, my dear! I’m so glad to see you. Welcome to your new home.’

That’s all for this morning,’ Ellen said.

Juliet pushed her exercise book away and slid off her chair.

‘Shall we go out now?’

‘We’ll just put the books away first.’

‘Then will you tell me some more about the girls at the High School?’

‘If you like.’

‘Oh, I do like!’

Juliet skipped up and down. Her short plaits, with their scarlet bows, danced on her shoulders. Ellen had expected Madeleine Rivers’ daughter to be fair, but the little girl whose head came round the door when her breakfast tray appeared on her first morning was dark, just beginning to grow leggy, with childish features still undefined. Ellen’s first impression of her face had been of the very clear blue whites round her bright, well-opened brown eyes.

‘Tell me some more about the play in the garden when the donkey’s head got stuck!’

Ellen was kneeling on the floor before one of the low

cupboards under the bookshelves. The library, being both scholastic and likely to be cool in hot weather, had been allotted to them for a schoolroom. They worked at the table where old Sir Robert Gressingham had gone through the farm accounts with his bailiff and sat late into the night reading the books on astronomy and astrology which filled half one side of the room. It was he, Mr Rivers said, who had cut the narrow door in the outer wall so that he could step straight out on to the English lawn that he had made and look at the stars.

Juliet, with a pile of books in her arms, stood just behind her governess’s neat back, looking down at the white shirt firmly and evenly tucked into the belt of the grey tweed skirt. A hairpin fell out of one of Miss Fenwick’s coils of hair and tinkled on the polished floor. She picked it up and put it back in the same place.

‘Mummie would like to cut all your hair off! She says it’s dowdy! But I think it’s beautiful! Your plaits must be much longer than mine. Can I see them down your back some time? Grannie Rose has long hair. I don’t like prominent waves.’

‘The word is permanent. It means that they last.’

Ellen knelt for an instant without moving, feeling the first faint breath of chill on her glowing happiness. But not to take too much notice of things that children repeated was a piece of wisdom bought by her years of experience.

‘Just a minute, Juliet. I want to make some more room in here for our books. Your mother said we could have the whole of this cupboard, but there’s something stuck in this corner. Ah!’

She dragged out a ball of dust fixed in a hoop of metal to a dusty stand with a coiled flex clotted with dust and cobwebs.

‘It’s only a dirty old lamp!’

‘Yes, but look!’

With the duster they had been using for the books, Ellen wiped off the thick coating. The lamp was a globe of the hemisphere made of dark blue glass, with clear glass for the stars.

‘It’s a map, do you see? A map of the sky with all the stars. We can plug it in somewhere, and they’ll light up, and then we shall be able to find them in the sky.’

‘Is that a map? It’s got no countries.’

‘There may be countries on all those stars. They may each be a world.’

‘Who lives there?’

‘We don’t know. We don’t know much about them yet.’

‘But you know a lot of things,’ Juliet said kindly. ‘I like doing lessons with you better than school.’

‘I’m glad you do. I like teaching you very much.’

The door in the wall opened and Charles Rivers put his head in.

‘Have you done with her, Miss Fenwick? Juliet, there’s a new calf in the Mandini shed, born this morning. Would you like to come and see him?’

Juliet skipped towards him, catching hold of his hand. To go anywhere with her father was always a treat, but she hung back in the doorway.

‘Can Miss Fenwick come, too?’

‘Of course, if she wants to.’

‘You show it to me another time, Juliet.’

‘She’s glad to be rid of you for a bit,’ Charles said without conviction, and Juliet laughed at a good joke.

But it was true that Ellen was glad to be alone. This was only her third morning at the villa, and she needed frequent intervals of solitude, for she could hardly contain all the enchantment of her new life. It had begun on the first morning

when she woke at dawn and saw the light coming between the curtains. She had jumped out of bed, sodden with sleep, and stumbled across to the window to see this unknown country which at bed-time the night before had only been darkness pricked by sparse lights. Now she saw that the villa stood on the crest of a hill with a valley below and the land rising beyond it. The serene lines of the Tuscan hills folded in like a stage set to enclose the formal garden, that sloped from beneath her window to a low wall. There were a few farms in the valley, and pale villas in clumps of trees spaced here and there on the hillsides, but no walls or hedges divided the fields, neatly patterned with the young veridian of corn or vine, broken by rows of silvery olives, or by the sharp, dark exclamation mark of a cypress. As yet untouched by sunlight, the scene lay in suspension, strange but familiar, so that Ellen, while transported with delight, felt at the same time that there was, after all, really no such thing as going abroad. She huddled back into bed again, and was asleep almost as soon as the bedclothes touched her chin, with that first half-waking vision of Tuscany printed for ever on her mind.

She stood now by the mahogany table holding the cold glass globe between her hands, fascinated by this solid piece of the magic. She stared into it as if it were a crystal and she might see in it what was going to happen to her in this new life. She could not believe that nothing would happen, that she would just teach Juliet for six months and go back to the Ainley High School in September. Already she felt different – in the clear light and the warm sun some heaviness had dropped from her body and spirit. She felt like a balloon filling with air, ready to take off. In need of anchorage, for she had been brought up to suspect pleasure, she looked down at the exercise book on the table whose first pages were covered

with Juliet’s round hand. She picked up a pen and corrected a spelling mistake, then put the book away with the others, lifted the globe on to the window-ledge and went out to stroll in the sun on the English lawn.

From the lawn steps led down to the vegetable garden, a patch stolen from the farm where, between the olives year after year old Giovanni, who was both caretaker and gardener, planted tomatoes and artichokes for the family, although since Sir Robert’s death they had never come to eat them. He came up now with a basket of salad for the kitchen. His face, which, like his clothes, was the colour of the Tuscan soil, crinkled into a smile of greeting. He answered Ellen’s ‘Buon giorno’ with a long sentence in Italian, which seemed to be about the weather. ‘Non capisco,’ she said – it was one of the first things she had learned – ‘Non capisco’; but he only smiled and nodded, as though a necessary courtesy had been exchanged; what she had understood was his good will and the rest did not matter. After he had gone round the corner of the house to the kitchen, his wife, Angelina, a little old woman who seemed to live always in the same dark blue dress faded by the sun nearly to lavender, came out of the door of their house in the north wall of the villa. She carried a bowl full of scraps for her one hen, a precious fowl which roosted in the wood beyond the garden gate. On her way back with the empty bowl she, too, greeted Ellen, and told her something, waving her hand from the bowl to the hen, now picking pompously among the scraps. Ellen nodded and smiled and this time did not trouble to say, ‘Non capisco’, which in a way was not true, for she understood that Angelina, like Giovanni, was pleased to see so much company again after the years when they had lived like two mice in the corner of the empty house. She saw a fair head and a pale blue sweater underneath the

olive-trees. Madeleine Rivers came up the steps to the lawn, and Ellen went to meet her. It was perhaps the greatest part of her happiness that not only was Juliet such a dear little girl, but her mother was so kind, and so utterly charming – the most charming person Ellen had ever known. She had never expected Mrs Rivers to seem younger than herself, although actually a year or two older, to be so gay, so considerate, to treat her with such simple friendliness. She liked Mr Rivers, and was beginning to be at home with him; he was kind to her and devoted to Juliet, and his dry humour often made her laugh, but for her he was not an illuminated figure. He was simply a necessary part of the happy family, which was something she had always been wanting, and had at last found.

Madeleine came towards her, smiling.

‘Lessons over? Good! Where’s Juliet?’

‘Her father took her to see a new calf at the Mandini farm.’

‘Oh! He didn’t ask me to go, too!’

‘They’ve only just started. I expect you could catch them up in a few minutes.’

‘No. They didn’t ask me to come, so I shan’t bother. Let’s go round to the piazzale and have our drinks in peace.’

She slipped her hand through Ellen’s arm. They walked along the flagged path under the villa’s creamy wall.

‘I do hope you don’t find it dull teaching a baby like Juliet, after much older girls?’

‘No, indeed; I shall enjoy teaching her. She’s very intelligent, and I’m glad to have a change.’

‘Have you always taught at the same school?’

‘Yes. Seven years. When I came down from Oxford I was going to America for a year. I got a scholarship to do some post-graduate work there, but my mother had her first heart attack just then, and I couldn’t leave her. I had to get a post

near her, and luckily there was one at the High School, which was my own old school.’

‘That was very bad luck, not being able to go to America!’

‘It couldn’t be helped.’

‘I suppose not. Didn’t you get away from home at all in the holidays?’

‘Sometimes for a few days when I could persuade a cousin to come and take my place, but it was too much responsibility for her in this last year or two. My mother was always upset when I went away, and it generally made her ill. It was very difficult.’

‘My dear, it must have been impossible! I don’t know how you stood it.’

‘It wasn’t as bad as that.’ But now, hearing it said by someone else, there rose up in Ellen a full realization of how very bad it had been. ‘I really like teaching. And there were other things that I enjoyed.’

‘What things?’

But Ellen felt that it was too difficult to explain to Mrs Rivers a life so remote from her experience. Most of her pleasures had been unpremeditated: a walk to school on a blowing spring morning, with the cloud-shadows sweeping over the hills and the mill chimneys in the valley flying flags of smoke; a fireside tea or Saturday afternoon walk with Alice; a new perception stirred in her mind by some book that she was reading. Even the extra half-hour in bed on a holiday or the cup of hot coffee in the staff-room at break on a winter morning came back into her mind. They belonged to life in the Northern industrial town where beauty was incidental and happiness a by-product. Here, where everything was beautiful, where life was arranged as a series of pleasures, Ellen felt that they would mean nothing. She chose by instinct

that part of her old life which seemed to connect with Madeleine’s world.

‘I had a lot to do with the Little Theatre. I used to help to produce plays, and produced one or two on my own, and I organized play-readings and so on. I used always to go there two evenings a week. There was a place where you could have coffee and talk. I enjoyed all that very much.’

‘I should think you would have died without it!’

Ellen, who thought that you did not die so easily, replied soberly:

‘It made a lot of difference.’

They crossed the courtyard and came through the archway on to the piazzale, meeting a wave of scent from the rosegarden, strong as the scent from a greenhouse, but fresher and sweeter.

‘All these roses in April!’ Ellen murmured, with a sigh of content.

Gastone brought the shaker and glasses. Ellen, accustomed at home to the occasional mild dissipation of a glass of sherry, had refused a drink on her first day, and asked anxiously for half one on the second. Now, with a feeling of abandoning herself recklessly to the stream, she allowed Madeleine to fill up her glass, and drank it quickly. This at once put a slight haze between her and the edges of the world, and emboldened her to say something she had been wanting to say for three days.

‘I’ve seen your mother act several times – twice in Leeds and once when we took the Sixth Form to Stratford. I do so much admire her! I don’t think anyone is better in Shakespeare! So often people act well but don’t give the lines their full value as poetry, but she does both.’

It appeared to Ellen that Mrs Rivers’ face, now slightly

swimming before her, looked pinched, almost haggard. She took a drink without answering. Ellen was conscious of some check.

‘I expect you’re tired of hearing people say these things.’

‘Oh, no, indeed I’m not! I’m always delighted and proud, especially when it’s people who know something about acting and understand what they are talking about.’

Ellen was inordinately pleased.

‘I don’t know much about it, really.’

‘Did you know that I was on the stage, too?’

‘No.’

The blunt negative dropped like a stone between them. Hazily aware of its fall, Ellen added:

‘I was hardly ever able to go to London. I only saw the shows that came round to us. I missed so many plays and people I should like to have seen.’

‘Oh, I was never famous. I was only on for three years before I got married. I wasn’t a success. In some ways I suppose I had a very easy start. I got parts, of course, without any difficulty because every management knew my mother. But in other ways it was much more difficult for me than for any other young actress starting. People expected too much of me. They compared me to my mother all the time, and watched to see if I was like her and if I was going to be as good. I always felt them doing that; I couldn’t forget it. You can’t imagine what it was like.’

‘I think I can, a little.’

‘Once, after I’d been playing Celia in As You Like It – the best part I ever had – and I thought I was doing it well, I heard two people talking. They said, “Pretty little thing; but she’ll never be another Rose Danby.” After that I just didn’t know how to go on to the stage! It was torture! I couldn’t

sleep for dreading the next performance. Luckily I got tonsillitis the week after and fell out of the cast.’

‘But you were so young,’ Ellen said. ‘How could they possibly tell what you could develop into! Of course it would have taken a few years for you to establish your own stage personality apart from your mother’s! But it would have come, and they would all have recognized it if you’d wanted to go on with a stage career.’

‘Well, I didn’t. I married Charles. I never acted again after I was married. I know my mother and all her friends really think of me as a failure.’

Ellen said diffidently:

‘I should have thought that most people would envy your life.’

Although still seeing the world through a slight haze, she was aware that some tension had relaxed. The charming face opposite to her was once again clear and smiling.

‘I’m so very glad,’ Mrs Rivers said, ‘that Helena Gressingham sent you to us. Juliet likes you so much, and I’m so looking forward to having your company this summer. Charles goes back next week, you know, when the Law Courts open. He can’t come out again till the end of July. I was rather nervous before you came because Helena Gressingham said you were so clever, and I thought you might be too strict with Juliet and despise me for having no brains. But you’re so sympathetic and understanding, I feel as if we’d known each other for a long time, and I’m sure we shall be real friends and have a lot of fun together this summer; don’t you think so?’

It had never been Ellen’s habit to make friends quickly. The people among whom she had grown up were chary of praise and reticent of enthusiasm, but such open-heartedness broke down her barriers, and she answered with sincere warmth:

‘Oh, I do! I can’t tell you how glad I am that I came. I think every moment of the day how lucky I am to be here.’

‘I’m so glad. I do want you to do one little thing for me. Will you?’

‘If I can.’

‘Let me do your hair differently, or cut it off. Your head is such a good shape, and nobody can see it with those Catherine wheels.’

‘Oh!’ Ellen exclaimed, ‘I’m so glad you said that to me.’ She added non-committally, ‘I’ll think about my hair.’

‘Yes, do. Let me give you another drink.’

‘No, no.’ Ellen shielded the glass with her hand. ‘I’m quite drunk already.’

‘You can’t be! Anyhow, what does it matter? I’ll give you half, if you like.’ She filled her own glass to the brim. ‘We’ll leave the ice for Charles.’

The car swung out of the back gates and into the main road that wound above the further valley. Here the hillsides sloped more steeply than those in front of the villa. The tiered vines ran down between the corn like stripes on a print, to a little stream half buried in grass. The sun was hot, the sky made of dazzling blue light. They met a creaking cart drawn by two white oxen, and were only able to pass it by driving half-way up the bank.

‘I don’t know why we had to go to the Warners’ again so soon,’ Charles grumbled.

‘Well, darling, they’re our nearest neighbours. This is country life.’

‘As a matter of fact, they are not our nearest neighbours. The Villa Caligari is a good mile nearer.’

‘It’s a much worse road to Caligari, and the old Contessa gives me the creeps.’

‘So do the Warners give me! She’s a bitch, and he’s like some awful automaton. He’s been dead for years, really. Why does he go on buying all that furniture and those pictures?

The house is stuffed full already, and he doesn’t care about any of them.’

‘He wants to have taste.’

‘Well, he never had, never can have and never will!’

‘Lucrezia has.’

‘She has too much of it! She’s been brought up to know the right things to like.’

‘Don’t you see, Charles, Grant is trying to live up to her. He said something about it to me. He feels that she belongs to the old civilized Europe, that Rome is her proper setting, and that he has to make it up to her for taking her out of it. That’s why they came back from America. He said that she just couldn’t stand it; she couldn’t live in that raw new world.’

‘Well, damn it, it wasn’t the rape of the Sabines; she knew what she was doing when she married him. Boldoni probably left her very poor. I knew the parents when I was in Rome. They were living with one servant in the corner of a crumbling old palazzo. Lucrezia’s got everything she wants from Grant, and manages to make him feel apologetic for giving it to her.’

In the back seat Juliet asked:

‘Fenny, who are the Sabines?’

‘They were some people a very long time ago who plundered Rome and carried off all the women to be slaves.’

‘Did they get back again?’

‘They didn’t want to,’ Charles said over his shoulder. ‘They liked taking it out of the Sabines.’

Madeleine turned round.

‘Daddy’s teasing! You’ll both enjoy going to Bronciliano. I want Fenny to see the villa and the garden, and Juliet likes Shand, don’t you?’

‘Yes. But he doesn’t like me much. And I don’t like Donata and Bianca. Silly little dressed-up babies, always crying!’

‘Shand, poor chap, doesn’t like anybody much. He was certainly the eggs in that omelette.’

‘Lucrezia says he likes the new tutor. He’s the third they’ve had since they’ve been here. The others couldn’t do anything with him.’

‘I expect they’ve always got mugs. Shand’s all right, really. They should send him to school.’

‘I can’t think why Grant doesn’t send him back to his own people in New England. I know he wants to go.’

‘I should think Lucrezia likes keeping the prisoner of the conquered country in her train.’

‘And, of course, Grant gives in to her about that, as he does about everything else. He’s afraid of her.’

Charles said with sudden vicious intensity:

‘He ought to beat her. It would be very much better for them all.’

‘Mummy, do you like the Warners?’

They all laughed. Charles said:

‘Mummy adores them. She isn’t happy unless she can go over there two or three times a week. Lucrezia Warner is her greatest friend.’

‘No, Charles, don’t tell her that nonsense. It’s like this, Juliet. When you live in a town you choose the people you go to see, but when you live in the country you go to see the people who happen to be there because you must see some people, and there are always things you like about them as well as things you don’t.’

‘When I’m grown up I’ll live in a town. Will you live with me, Fenny?’

‘We’ll see when the time comes.’

Madeleine turned to Ellen.

‘The Warner family is a mix-up. Grant is American, Lucrezia’s Italian. They’ve both been married before. Shand is – what is he, Charles? Twelve? He is the first wife’s son. She was American, and after she died he lived with Grant’s sisters in New England until the second marriage. Donata is a year younger than Juliet.’

‘A year and a half,’ Juliet interrupted fiercely.

‘Well, a year and a half, then. She’s Lucrezia’s child by Boldoni, her first husband, who died. Bianca is the child of this marriage, born in America. Her name is really Blanche, and Grant always wants to call her that, but—’

‘But,’ Charles said, ‘what Grant wants is of no consequence.’

‘I dare say,’ Madeleine replied sharply, ‘that Lucrezia puts up with a good deal we don’t know about.’

‘I should think that’s most improbable.’

Ellen felt a momentary discomfort, without knowing why, as the car turned a corner and the Villa Bronciliano came in sight. She was looking forward to seeing this exotic family. The week that had turned her from Miss Fenwick to Fenny had made her very much at home with her employers, but had not dimmed her enchanted delight in everything around her. She did not say very much about it, for she saw that they enjoyed the villa and the countryside in a different way. To them this was one of many beautiful places that they had seen; they appreciated the loveliness, but took it as a natural part of their lives. Ellen, much as she liked them all, looked forward to those hours in the day when she could stroll out alone and draw into herself the shapes of the hills and the rounded tiles of a roof, the sun-faded apricot of a farmhouse wall. Even in the villa she liked to wander through the rooms sometimes when they were out or resting, or to sit in the

courtyard gazing at the contrast between the bright light and the violet-tinted shadow on the pale stone. She knew that she was gaping, and knew, too, that the Rivers did not gape, probably never had. Even in Juliet there was already a kind of experience that precluded more than a measure of astonishment. Juliet liked the animals and the farms and the wild flowers, but was indifferent to house or scenery. She enjoyed acting plays and stories with her dolls, hearing about the Ainley High School, or reading. Ellen thought she was too much with grown-up people, and was glad that they were going to a house where there were some children. In her opinion even babyish little girls and a difficult boy would be better than no young company at all for her child.

The Warners were in the loggia in front of their villa. Lucrezia Warner came running to meet them with cries of pleasure – excessive pleasure, Ellen thought – embraced Madeleine with fervour, and gave her hand graciously to Charles. Except for her corn-coloured hair and arched eyebrows, she was not beautiful, but she had an elegance that made Madeleine look suddenly young and unformed. An assured feminine confidence hung about her like her scent. She said, ‘How glad I am to see you, darling!’ to Juliet, who submitted passively to be kissed. She shook hands with Ellen without looking at her, and Ellen disliked her at sight. Grant Warner, who came up very slowly behind his wife, was tall and grey, with a square, pale face and melancholy eyes. He seized at once upon Charles, and began to talk to him about a sale he had been to near Bologna. He had bought two sopra porte and had had them made into bed-heads, and he carried Charles off to see them. Lucrezia and Madeleine sat down in basket chairs under a tasselled wisteria.

Lucrezia looked at Ellen and Juliet.

‘Juliet, my pet, wouldn’t you and your governess like to go and find the children? I think they are in the lower garden.’

‘Would you take her, Fenny?’ Madeleine’s smile apologized for Lucrezia’s abrupt dismissal. ‘You ought to see the garden; the view’s so lovely.’

But Ellen knew that Madeleine, too, wanted to get rid of them so that she could gossip with Lucrezia. She felt a small stab of jealousy as she turned away with the child.

On the other side of the villa, on a lawn bordered by a cypress hedge, two little girls, one dark and one fair, were playing with an elaborate dolls’ dinner-service. The dishes were heaped with rose-petals and fading blooms of wisteria. The elder child, very like Lucrezia except for her dark hair, jumped up and came to meet Juliet with a good imitation of her mother’s manner. The little one went on stolidly filling soup plates from a tureen of water in which floated daisyheads and blades of short grass. The children were both dressed in white embroidered muslin frocks, much frilled and tied with coloured ribbons. Beside them Juliet in her grey flannel skirt and red shirt looked boyish and leggy, a schoolgirl with two nursery children, but Donata’s gestures and movements were those of a little grown-up woman as she waved her hand towards the dinner-table inviting Juliet to join in the game. Juliet, who would have loved to have the dinner-service for her dolls at home, here gave it a disdainful glance, but could not refrain from saying, ‘You’ve got no vegetables. Why didn’t you make a salad with green leaves?’

‘But that would be charming,’ Donata said. ‘Let us get some.’

They moved off together. The little one went on unconcernedly ladling the water into the soup plates with a fat but steady hand.

Ellen thought that the children would get on with each other better if she left them alone. She strolled down the steps into the garden. An avenue of green turf ran between the hedges of clipped cypress to a grove of lemon-trees in terra-cotta stone jars. In the middle was a fountain – a stone boy with his head thrown back playing on a reed from which a jet of water sprang into the air and curved down to the pool. At first Ellen thought that she was alone, but as she walked round the pool she saw a living boy sitting on the rim with a book on his knee. Hearing her footsteps he looked up and scowled. He was at that age, just beginning to shoot out of childhood into adolescence, when the growth seems to be mostly in the wrists and ankles. He was gangling, dustyheaded, with his father’s square face, but with a wide mouth not in the least like his father’s, and with very deep-set blue eyes. His scowl relaxed a little as he saw Ellen, but he looked wary, and did not close the book on his knee.

‘I’m sorry I disturbed you. You must be Shand?’

‘Yes. How did you come here?’

‘I came with Mrs Rivers. I’m Ellen Fenwick, Juliet’s new governess.’

‘Oh, I see. I thought you didn’t look like one of Lucrezia’s friends.’

Not sure whether this was to be taken as a compliment or not, but quite sure that he wanted her to go, Ellen said, ‘Oh, no. I haven’t seen her before. I only came out from England a week ago,’ and was turning away, when he shut his book and put a hand on the rim of the pool.

‘You can sit down here if you like.’

‘Thank you.’

The stone was warm as new bread.

‘What are you reading?’

‘Huckleberry Finn. Do you like Italy?’

‘So far as I’ve seen I love it.’

‘I hate it.’

‘It’s the most beautiful country I’ve ever seen!’

‘Perhaps you haven’t seen many.’

‘No, I haven’t; but I’ve seen enough to know how beautiful this is. Why, look there in front of us.’

Before them, at the end of the garden, a gap in the cypress hedge opened to a view of the towers and roofs of Florence and the lovely valley of the Arno stretching away between sunny hills.

‘I suppose that’s OK. But I don’t like the Italians.’

‘I hardly know any yet, except the servants, who all seem very nice.’

‘Yes, servants are nice. But the rich ones are mean and greedy and treacherous and conceited and cruel.’ He seemed to have relieved his mind by this diatribe, for his frown relaxed. ‘Has Juliet come, too?’

‘Yes; she’s up there with your step-sisters. They’re having a doll’s dinner-party.’

‘Donata isn’t even my step-sister. Her father was Italian, too. Blanche was born in America, and as soon as I can, I shall take her back there.’

He said this with renewed defiance, but Ellen only replied, ‘Yes, I expect everybody wants to go back to their own country,’ and then wondered whether for herself in six months’ time that would be true. ‘Oh, there’s a fish in the pool.’

‘It’s full of gold-fish.’

She leaned over the water, watching the gleam of coral and silver under the surface.

From the terrace above them a man’s voice called: ‘Shand!’

‘Hya!’ As the echo died among the cypresses, Shand added, ‘That’s Daniel, my tutor.’ The sullenness had altogether cleared from his face. ‘He’s new, too. He’s only been here a month. He’s different from all the others. He’s an artist, and he paints beautifully. Come and find him.’

But Ellen hung for a moment longer over the pool, feeling the warmth of the sun on her bent head, catching the gleam of a bright fin. She put out her hand and caught in the palm the jet of water from the boy’s pipe. The cold drop trickled from her fingers to her wrist and splashed on the stone beneath. Some instinct made her unwilling to mar that tranquil moment and go on to the next.

Then she looked up and saw a young man standing on the turf between the cypresses.