BY JENNY COLGAN

BY JENNY COLGAN

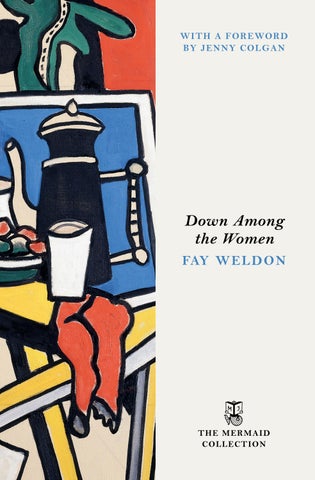

First published in 1971, Fay Weldon’s Down Among the Women was her second novel. It is being reissued as one of Penguin Michael Joseph’s Mermaids series – a collection of unjustly neglected works of popular mid-to-late-twentieth-century literature. Each Mermaid is introduced by a modern writer, reflecting on the author and book’s importance to the world in which it was published and its continued relevance today.

This Mermaid is introduced by Jenny Colgan, international bestselling author of over fifty novels, including Meet Me at the Seaside Cottages.

To hear more about The Mermaid Collection, visit www.penguin.co.uk/TheMermaidCollection

PENGUIN BOOK S

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published by William Heinemann Ltd 1971 This edition published by Penguin Books 2025 001

Copyright © The Estate of Fay Weldon, 1971 Foreword copyright © Jenny Colgan, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

This book is a child of 1971 and may contain language or depictions that some readers might find outdated today. Our general approach is to leave the book as the author wrote it. We encourage readers to consider the work critically and in its historical and social context

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception

Set in 10.5/14.25pt Sabon LT Std

Typeset by Six Red Marbles UK , Thetford, Norfolk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn: 978– 1– 405– 98264– 1

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

Ihave never drunk the famous tequila with the worm in the bottom of it, but I imagine it is not entirely unlike the experience of reading this book. Sharp, biting, with the sense of something utterly hideous lurking underneath it all: that’s Down Among the Women.

It is bracing, muscular, funny, and for a book over fifty years old, the freshness of the prose feels like it was written yesterday. Fay Weldon was, you never forget, a superior craftswoman, her trade honed in advertising. The milling voices of the young women we follow over twenty years –Scarlet, Emma, Helen, Jocelyn and Sylvia – never get mixed up or jar; the contemporary novels it most resembles, with its jostling chorus desperate to tell you how terrible things are, is, oddly enough, Hilary Mantel’s Beyond Black or George Saunder’s Lincoln in the Bardo. A cluster of anguished shouts into the void, when they feel nobody might ever listen. But, in fact, someone was listening: and Weldon makes us listen in our turn.

Down Among the Women was written in the 1970s, but is

describing the world of Weldon’s own youth, the 1950s, and boy, does she have a lot to tell us.

From the routine domestic violence the women more or less expect; the lack of contraception; the strange, desperate, warscarred men; a barely nascent welfare state and the hideous, all-encompassing punishment – only for women – for having children out of wedlock; it’s all here, and it’s impossible to stop reading it.

Once, we lucky daughters of the next generation could have read this book simply to revel in the joyous acid of Weldon’s prose: luckless child bride Susan with ‘the same kind of showing off she has always done, from puffed sleeves as a little girl when no one else had them, to passing round the telegram at school which said her brother had been killed in action’, or how Audrey ‘likes rolling rubbers on, the same way she likes squeezing spots, plucking hens and gutting fish.’

These days, however, in the shadow of a growing men’s movement that romanticizes this precise era, we can’t afford to be too complacent. The world within these pages is precisely what a lot of people, not just men, want us to return to: desperate, loveless marriages Jordan Peterson would undoubtedly approve of; otherwise blame, shame and impoverishment for women, even as Wanda, Scarlet’s divorced and ruined (yet strongly defiant) mother, has to carry her own squares of linoleum from grubby rental to grubby rental.

Even the main desperate tragedy of the book can be traced directly back to men on a macro, not an intimate scale, when they try and bend the entire world to their ends. Weldon tackles the horrors of war with characteristic verve: ‘Let us praise’ she laments, ‘truckloads of young Cairo girls, ferried in for the use of the troops, crammed into catacombs beneath the desert floor . . . where are their post-war treats; their grants,

their demob suits, their cheering crowds? Lost to syphilis, death or drudgery. Those other girls scooped up from all the great cities . . . Cairo, Saigon, Berlin, Rome. Where are their memorials? . . . Let us now raise a monument in the heart of the London Stock Exchange. Let us call it the Tomb of the Unknown Whore. Let the Queen pay homage once a year. Whose side is she on, anyway?’

This makes the book sound like a downer: it isn’t. It is often gleefully naughty: Susan’s mother is summed up wickedly in a single paragraph and never even gets her own name: ‘she cared that her children should reflect credit on her; she did not care for her children. She did not care for her husband; she did not care for life itself. She played bridge, and caught ‘flu, and waited for life to pass her by in as comfortable and orderly a way as possible.’

Weldon herself was of course notoriously naughty. She loved nothing more than winding people up. The fact that she was still being outrageous up to her late eighties was in itself glorious (she had figured out that the quickest way to get in the papers whenever she had a new novel out was to say something utterly appalling at a book festival) – and I have rarely seen more devoted book festival audiences than Fay’s, whenever she came on. Because those women knew. They knew the truth in Fay’s writing, in the unfair world, particularly for unapologetically clever women, and it was thrilling that Fay gave it a voice; that funny, sweary, shocking, rude, furious voice, bursting and screaming at the unfairness of it all, blowing it wide open for what it truly was.

She had that rarest thing, so hard to find: utter authenticity. She revelled in writing however she wanted to write, just how a man would; writing that was cruel or included lots of swearing or sex only made her more popular and successful

(culminating, of course, in the behemoth that was The Life and Loves of a She-Devil, still the rudest thing most people ever saw their mothers watch on television).

Weldon certainly didn’t care about the pressure, still prevalent today, to make female main characters likeable in a way that male leads never have to be (although both Scarlet and Wanda in this novel are often sympathetic, if vile to one another). She was fearless in a man’s world, standing up at the Booker Prize ceremony in 1983 and demanding that publishers treat their authors and staff with more respect. She pushed boundaries in a way that we still need today. We still have to remind young women that the right to vote, own our home and keep your own damn children was hard-won by ornery creatures exactly like Fay, and we owe it to her to preserve it, for the 30 per cent of today’s young women who don’t call themselves feminists, as well as the rest of us.

Down Among the Women is a classic. Fay was noisy in an era when women were expected to be quiet. She used her voice and took up space; she said what she felt; she brought energy and fun. It is a perfect snapshot of its era, and should be read by every dumbass politician and two-bit con-artist harking back to some imaginary earlier, better time; by the terminally online announcing that women’s rights have gone ‘too far’ or are ‘being hoarded’; by every young woman who needs to know how far we’ve come, how far we have yet to go.

It won’t. But at least you are holding it in your hands, and we shall call that a start.

Jenny Colgan, 2025

Down among the women. What a place to be! Yet here we all are by accident of birth, sprouted breasts and bellies, as cyclical of nature as our timekeeper the moon – and down here among the women we have no option but to stay. So says Scarlet’s mother Wanda, aged sixty-four, gritting her teeth.

On good afternoons I take the children to the park. I sit on a wooden bench while they play on the swings, or roll over and over down the hill, or mob their yet more infant victims – disporting in dog mess and inhaling the swirling vapours that compose our city air.

The children look healthy enough, says Scarlet, Wanda’s brutal daughter, my friend, when I complain.

The park is a woman’s place, that’s Scarlet’s complaint. Only when the weather gets better do the men come out. They lie semi-nude in the grass, and add the flavour of unknown possibilities to the blandness of our lives. Then sometimes Scarlet joins me on my bench.

Today the vapours are swirling pretty chill. It’s just us

women today. I have nothing to read. I fold the edges of my cloak around my body and consider my friends.

One can’t take a step without treading on an ant, says Audrey, who abandoned her children on moral grounds, and now lives with a married man in more comfort and happiness than she has ever known before. She, once imprisoned on a poultry farm, now runs a women’s magazine, bullies her lover and teases her chauffeur. How’s that for the wages of sin? With her children, his children, her husband, his wife, that makes eight. Eight down and two to play, as Audrey boasts. With the chauffeur’s wife creeping up on the outside to make nine.

Sylvia, of course, got into the habit of being the ant; she kept running into pathways and waiting for the boot to fall. Sylvia too ran off with a married man. The day his divorce came through he left with her best friend, and her typewriter, leaving Sylvia pregnant, penniless and stone-deaf because he’d clouted her.

How’s that for a best friend? You’ve got to be careful, down here among the women. So says Jocelyn, respectable Jocelyn, who not so long ago pitched her middle-class voice to its maternal coo and lowered her baby into a bath of scalding water. Seven years later the scars still show; not that Jocelyn seems to notice. In any case, the boy’s away at prep school most of the time.

Better not to be here at all, says Helen to me from the grave, poor wandering wicked Helen, rootless and uprooted, who decided in the end that death was a more natural state than life; that anything was better than ending up like the rest of us, down here among the women.

It is true that others of my women friends live quiet and happy married lives, or would claim to do so. I watch them

curl up and wither gently, and without drama, like cabbages in early March which have managed to survive the rigours of winter only to succumb to the passage of time. ‘We are perfectly happy,’ they say. Then why do they look so sad? Is it a temporary depression scurrying in from the North Sea, a passing desolation drifting over from Russia? No, I think not. There is no escape even for them. There is nothing more glorious than to be a young girl, and there is nothing worse than to have been one.

Down here among the women: it’s what we all come to.

Or, as I heard a clergyman say on television the other night, bravely facing the challenge of the times; ‘There’s more to life,’ he said, ‘more to life than a good poke.’

Wanda’s flat, at the present time, is two rooms and a kitchen in Belsize Park. It won’t be for long. Wanda has moved twenty-five times in the last forty years. She is sixty-four now. Rents go up and up. Not for Wanda the cheap security of a long-standing tenancy. Wanda turns her naked soul to the face of every chilly blast that’s going: competes in the accommodation market with every long-haired arse-licking mother-fucking (quoting Wanda) lout that ever wanted a cheap pad.

Wanda’s flat then, twenty years ago, when we begin Byzantia’s story, was two rooms and a kitchen in another part of Belsize Park. Some women have music wherever they go, Wanda has green and yellow lino. Scarlet, who at this time is twenty, has been sleepwalking on this lino since she was five and last felt the tickle of wall-to-wall Axminster between her toes. That was before Wanda left her husband Kim in search of a nobler truth than comfort.

The lino used to be lifted, rolled, strung, tucked under some male arm and heaved into the removal van. Presently it

cracked and folded instead of curling itself gracefully, and the male arms became impatient and scarcer, so Wanda hacked it into square tiles with a kitchen knife, and now when it’s moved it goes piled, and Wanda carries it herself. Amazing how good things last. The lino belonged in the first place to Wanda’s lover’s wife. This lady, whose name was Millie, bravely threw it out along with the past when she discovered about Wanda and her husband Peter – Peter for short, Peterkin for affection – but depression returned, sneaking under the shiny doors (three coats best gloss, think of that, in wartime!), slithering over the purple Wilton (pre-war stock), grasping poor Millie by the neck and squeezing until she died of an asthmatic attack.

Wanda and Scarlet are preparing for the Thursday meeting of Divorcées Anonymous. The year being 1950, a group such as this is a rarity, and its lady members the more amazed at their fate. Scarlet, in the arrogance of youth, thinks they deserve their pain – how they complain, how grey their skin, how vile and orange their lipstick. How should any man wish to remain with such miseries; why should such miseries wish to remain with any man? Scarlet is nine and a quarter months pregnant: she is heavy, but she glows, she is twenty; she has to reach out over her belly to butter the water biscuits and arrange the wedges of basic cheddar with which each is topped.

Listen, now. Wanda sings as she scours the coffee pot. This is before the days of instant coffee. She will use Lyons coffee and chicory mixture, which comes in a blue tin. Wanda is a large, heavy-boned, unpretty woman with a weathered skin, and eyes too deep and close together for their owner to be taken as anything other than troublesome. In an age when women still walk with toes pointed delicately outwards, Wanda

strides ahead, and makes others nervous. Let her granddaughter Byzantia, now curled head-down inside Scarlet, be grateful. Oh fuck! cries Wanda hopefully; oh bugger! she complains, in the days when words could still be wicked, and so she helps bring about a new world.

No wonder she has no husband; no wonder the Divorcées Anonymous munch her hideous water biscuit offerings with such helpless disdain.

Listen, now. Wanda sings as she scours the coffee pot. Wanda would have looked good in uniform, but they never let her have one. When Wanda walked into this headquarters or that, and demanded her right to help her country, there would be so much shifting of weights and pressures behind closed doors that even Wanda could not persevere. Why? Because she carried a Party Card and named her child after the blood of martyrs? How could that be? Was not Russia our ally? Nevertheless, there it was. She, who would have looked so good in Air Force glory, or Wren gloss, or even A.T.S. norm, had to do without. Wanda is always having to do without. If it’s not her own necessity, it’s Scarlet’s.

Listen, now. Wanda sings as she scours the coffee pot. Thinks herself lucky to have coffee. Millions in Europe still do not.

‘Ta-ra-ra boom de-ay! Did you have yours today? I had mine yesterday, That’s why I walk this way.’

Scarlet is disconcerted. Scarlet is offended. Scarlet, impressed by the workings of her own body, is having a fit of sanctimonious motherhood. Scarlet believes – for this one suspended

week – in love, life, mystery, meaning, sanctity. Byzantia lies very quiet and kindly allows her mother these few days of illusion. She is seven days late. Scarlet thinks she is a boy. So does Wanda.

‘I know it’s a boy,’ said Scarlet, in the sixth month. ‘But what can you possibly know about it?’

‘It’s a burden,’ said Wanda, simpering. ‘It’s a boy.’

Scarlet gritted her teeth and folded herself metaphorically around her precious burden, which kindly went patter patter patter beneath her ribs. When the doctor asked her if the baby had quickened she said she didn’t know. She felt something sometimes but thought it might be indigestion.

He looked at her as if she was a fool, reinforcing her own opinion of herself.

Wanda sings. The coffee pot is scoured. It shines in tinny splendour, worn thin by wire wool. This is before the days of detergents for the masses. The rivers of England still flow cool, clear and sweet. The towns are filthy; they have gone twelve years without paint, but in the country the hedgerows grow green and thick, still unperverted by insecticides, and the blackberries are glorious. Wanda and Scarlet would rather die than live in the country. Wanda tells horror stories of the fate of women who have done so.

‘Don’t sing that,’ says Scarlet.

‘Poor little Scarlet,’ says Wanda, ‘poor baby. Did it have a nasty rude Mummy then?’

‘Yes.’

‘Opportunity would be a fine thing,’ says Wanda. ‘Breathes there the man with soul so dead who would not kick your mother out of bed?’ She is unkind to herself. At forty-four she is at her most handsome: little men like her. She does not like little men. She waits, and will wait for ever for a tall handsome bully who will penetrate her secret depths.

‘Can’t stand men with little cocks,’ she cries, but what she means is, if only there was someone who would stay long enough to listen, go deep to touch my secret painful places, so I would feel again I was alive.

And how is Scarlet to know this? Scarlet sees a rude, crude mother. Scarlet scowls.

‘What kind of mother are you anyway?’ she asks.

‘Bad,’ replies Wanda, with satisfaction, and Scarlet moans in outrage. Wanda is egged on. She sings again.

‘Ta-ra-ra boom de-ay, Have you had yours today? I had mine yesterday, That’s why I walk this way.’

‘I feel sick,’ says Scarlet. Her face has altogether lost its look of cosmic satisfaction; it nods mean and crabbed on top of her swollen body. She slices radishes stolidly in half, instead of bothering to carve them into the pretty flower shapes she normally makes.

‘Good,’ says Wanda.

Scarlet’s eyelids droop lower. She’s in a full-scale sulk. Nothing annoys her mother more. Scarlet has a round smooth face; her mother thinks she looks half-witted; certainly the more angry and miserable she becomes, the more stolid she appears.

‘Pull yourself together,’ says her mother sharply. ‘Don’t look like that.’

‘Look like what?’ Scarlet drawls.

‘Like I’ll have to support you for the rest of my life, let alone your bloody bastard.’

‘Every harsh word you speak,’ says Scarlet, ‘goes flying off into infinity, to bear witness against you.’

Wanda can’t bear such statements. Scarlet has become very good at making them. Wanda sings again.

‘Please,’ says Scarlet, ‘or you’ll bring it on.’

‘What else do you think I’m trying to do?’ asks Wanda. ‘Their brains get short of oxygen if they’re overdue, don’t you even know that? Yours will need all the I.Q. points it can muster, I imagine. I am doing you a favour. Shall I tell you the story of the milkman, the lady and the letter-box?’

‘No,’ says Scarlet.

Wanda tells the story.

‘There was once a randy young milkman,’ says Wanda, ‘who was accustomed to calling on a certain lady at seven in the morning, when he was half-way through his delivery round. The lady’s husband was on night duty. For a time all went well, in fact so well that the milkman, reluctant to miss a second of his precious time, would unzip himself as he ran up the garden path. He would then thrust his you know what through the letter-box so that she wouldn’t mistake him for another and open the door, all naked and waiting, to some stranger. One day, alas, the door was opened not by her, but by none other than her husband. Was the milkman taken aback? Only for a second. “If you don’t pay your fucking bill,” cried the milkman, “I’ll piss all over you.” ’

Scarlet doesn’t even smile. Wanda feels depressed. The coffee pot is boiling. She turns it upside down to filter it through; something inside goes wrong and boiling coffee bubbles over her hands. Wanda, stoical to the point of mania, does not scream or even complain, but holds her poor red hand under the tap.

‘I wish you’d grow old gracefully,’ says Scarlet presently. ‘I wish you’d grow old,’ says Wanda, with bitterness. ‘I wish you’d grow old and see what it’s like.’

‘You’re not old,’ says Scarlet with unexpected kindness. Perhaps she is touched by her own good nature. At any rate she starts to cry.

‘What’s the matter with you?’ asks Wanda, surprised. She can’t bear to see Scarlet cry. She thinks it might start her off too, and Wanda hasn’t cried since the day before she left Kim, Scarlet’s father, back in 1935.

So Wanda sings, sweetly, as a benison, the mellifluous notes of Brahms’ lullaby.

‘Hush, my little one, sleep, Fond vigil I keep, Lie warm in thy nest

By moonbeams caressed –’

Scarlet stops crying. She thinks perhaps Wanda means it. Something shifts in her universe. Cog wheels unlock, re-lock. The universe continues, but differently. What is happening? Her baby turning, unlocking? The waters shifting, slopping, heaving? No, it is the fact that Wanda is being sentimental. Scarlet gapes.

‘Shut your mouth, for God’s sake,’ says Wanda, and Scarlet obligingly closes it, for she has seen a tear in Wanda’s eye and is frightened. Wanda, of course, has no mascara to run. Wanda wears brilliant lipstick, to give more shape and vehemence to her words, but otherwise has no time for make-up, which she sees as cowardice. It is a pure and leathery cheek which the tear runs down, and still only forty-odd years since she was born so tender, smooth and throbbing.

‘I wish,’ says Wanda hopelessly, ‘I wish things didn’t have to be the way they are. Why did you have to go and do it?’

It is as well the bell rings, because Scarlet is feeling quite

sick from insecurity. She can bear her mother’s anger, spite and indifference, and can return them in kind, but she cannot bear her mother to be unhappy.

It is the first of the ladies. A brave one this, in dirndl skirt and peasant blouse, with dangly earrings and bright eyes. Lottie. She ran off with a lover who ran off from her, and her husband wouldn’t have her back. And why, as she herself says, the hell should he? Poor lady, poor brave Lottie, she died of cancer two years later, drifting painfully into nothingness in a hospital bed. She wrote to tell her husband she was ill, but he didn’t come to visit her. Well, why the hell should he? Thrown-away spouses, says Wanda, lying, are like thrown-away trousers, soon forgotten. You have killed them in your mind: their real death is irrelevant.

This evening at any rate Lottie is happy, excited and animated. She puts on the gramophone; embraces Scarlet and tells her generously that she’s a good brave girl and that she personally thinks unmarried mothers are to be pitied not blamed. She tells Wanda life begins at forty. She munches the water biscuits without noticeably wincing and drinks her coffee gratefully; tells Wanda about a good job in the Civil Service she has managed to land, untrained though she is, and announces that she is looking forward to a happy future without men.

Poor Lottie.

She has come early, she says, to get in her message of good cheer before the others arrive and swamp her good spirits. She is quite right. They swarm into the tiny room like a tide of despair. Scarlet goes to bed. They regard her, and she knows it, as Wanda’s cross.

Down here among the girls.

How nice young girls are, especially when their own interests are not at stake, but even when they are.

Next morning a delegation of Scarlet’s friends climb the stairs to the flat.

Scarlet is more embarrassed than grateful. She feels this morning she can’t get up. She lies there on her back, her extremities flapping feebly, like a piece of crumpled paper held down in a draught by a paper-weight.

Jocelyn, Helen, Sylvia and Audrey crowd into Scarlet’s tiny room. They have to pass through Wanda’s room to reach her. They are frightened of Wanda. They think she is mad, bad and dangerous to know. They think she probably drinks. They think she is what is wrong with Scarlet. They may well be right.

‘We thought if we all gave ten shillings a week,’ says Jocelyn, ‘that would be two pounds. That would help. It would pay the rent somewhere, anyway. And we could get up a collection as well.’

How full of confidence and kindness they are. Their eyes are misty with emotion. Scarlet is only conscious of Wanda pissing herself with laughter in the next room. It is one of Wanda’s weaknesses, in fact. Too much excitement, sex or mirth and her bladder tends to give up. It seems an alternative to weeping.

Scarlet could never tell her friends a fact like this. They have been too delicately reared – except for Audrey, who was brought up on cheerful fish and chips in a Liverpool slum, and Audrey cannot be relied upon to keep a secret.

The others have escaped their parents or believe they have.

Jocelyn, who was head girl of a good private school, writes home every week, visits once a month. She is, in these days, a rather plain, rather jolly, popular girl with legs made knobbly by hockey blows. She likes to drink gin and tonic with young rugger-blues in smart pubs; one will sometimes take her to

bed and they will have a jolly, surprising, unemotional time. She will get up out of bed, bright and healthy, bathe, shave her legs, put on a white dress, and play a good game of tennis with her boyfriend if he’s available and a girlfriend if he’s not. She got one of her boyfriends in the eye once, with the edge of her racket, and eventually he lost the sight in it.

Jocelyn was at college with Scarlet. She took her degree in French. Now she is looking for a job.

Scarlet got sent down for failing all her exams, twice over. Now Scarlet is in trouble.

Sylvia, who did classics, and shares a flat with Jocelyn, has been in trouble already. She had an abortion when she was fifteen but can’t really remember it. (Jocelyn, who was at school with Sylvia, and now more or less looks after her, seems to know more about it than Sylvia herself.) Sylvia is training to be a Personnel Officer at Marks and Spencer: she has a nice quiet boyfriend called Philip, and is, these days, a nice quiet girl. Sylvia is sorry to see Scarlet in this condition, but is frightened lest Scarlet suddenly bursts and spatters them all with blood and baby, which seems likely. Scarlet wears only a semi-transparent nightie; she is too far gone to consider decencies. Scarlet’s nipples are brown and enlarged. Sylvia stares. Scarlet droops.

Even Helen, beautiful Helen, with her green witch eyes, her blood-red nails, her high white bosom, makes little impression on Scarlet today. Helen has been married and divorced already, in Australia. What a mysterious and magic creature this orphaned Helen seems, moving as she does in a grownup world, where the others feel they still have no right to be.

Helen allows Audrey to share her flat, and pay the rent.

Helen paints pictures, starves to buy paint, loves and is loved by men who have their names in the papers.

Audrey, who types in a solicitor’s office, which is where her degree in English literature has led her, not only pays the rent, but washes and irons Helen’s clothes, and thinks herself privileged to do so.

These kind pretty girls, with their tightly belted waists and polished shoes, seem to Scarlet to come from an alien world. She can’t think why they bother with her. There is, though Scarlet can’t think why for the moment, something very wrong about their presence here.

Scarlet’s stomach hardens and goes rigid. Scarlet frowns. The feeling is not so much unpleasant as an unwelcome reminder that her body now thinks it owns her.

‘Is something the matter?’ asks Sylvia, anxiously.

‘Just getting into practice,’ says Scarlet.

‘Aren’t you frightened?’ whispers Sylvia.

‘Don’t put thoughts into her head,’ says Jocelyn briskly. ‘Scarlet is young and healthy. Think of native women. They just have their babies in a ditch, and then get up and go on harvesting or killing deer or whatever they’re doing.’

‘And then they go home and die,’ says Audrey. ‘I had two aunts died in childbirth within a week. Mind you they both had the flu, I’m not saying it’s going to happen to Scarlet. And London hospitals are better, they say, than Liverpool. Though awful things do happen.’

‘I’m not frightened,’ says Scarlet, and it’s true, she isn’t.

Helen gives a little disbelieving laugh but says nothing. Sometimes she reminds Scarlet of Wanda.

‘Anyway,’ says Scarlet, hoping they will all go away, so she can ease herself out of her transfixed position, ‘it’s very kind of you, and I may take your offer up.’

She doesn’t believe in any of it. She doesn’t believe that Wanda is her mother; she doesn’t believe she is pregnant; she

doesn’t believe she has no job and no money; she doesn’t, if it comes to it, believe she’s a day older than five. She has been sleepwalking for years and years. She has summoned up these four friends from some dim fantasy.

‘I know what’s wrong,’ she says suddenly, looking round the startled girls, ‘where are all the bloody men?’

She shuts her eyes and opens them again. They’re still there. She can’t understand it.

Down among the girls.

Contraceptives. It is the days before the pill. Babies are part of sex. Rumours abound. Diaphragms give you cancer. The Catholics have agents in the condom factories – they prick one in every fifty rubbers with a pin with the Pope’s head on it. You don’t get pregnant if you do it standing up. Or you can take your temperature every morning and when it rises that’s ovulation and danger day. Other days are all right. Marie Stopes says soak a piece of sponge in vinegar and shove it up.

The moon, still untouched by human hand, rises, swells, diminishes, sets. Nights are warm; the wind blows: men are strange, powerful creatures, back from the wars: the future goes on for ever. Candles glitter in Chianti bottles; there are travel posters on the walls; the first whiffs of garlic are smelt in the land. To submit; how wonderful. If you don’t anyway, little girl, someone else will. Rum and Merrydown cider makes sure you do, or so they say. Quite often it just makes you sick. There is a birth control clinic down in the slums. You have to pretend to be married. They ask you how often you have

intercourse – be prepared. They say it’s for their statistics, but it’s probably just to catch you out. They have men doctors there too. A friend knows one – he’s a tiny little man who shows her dirty pictures and likes someone else to watch. Are they all like that? And how do you know, if you go to the clinic, that you won’t get him?

Every month comes waiting time: searching for symptoms. How knowledgeable we are. Bleeding can be, often is, delayed by the anxiety itself. We know that. It’s the fullness of the breasts, the spending of pennies in the night, the being sick in the mornings you have to watch out for. Though experience proves that these too can be hysterical symptoms. And what about parthenogenesis? Did you know a girl can get pregnant just by herself? Consider the Virgin Mary. Try hot baths and gin. There’s an abortionist down the Fulham Road does it for £50. But where is £50 going to come from? Who does one know with £50? No one. Could one go on the streets? And why not? Jocelyn once said, when drunk, it was her secret ambition. No, not to be a courtesan. Just a street-corner whore.

Down among the girls.

Helen has a diaphragm, and a gynaecologist. He fitted her privately, majestically, wearing a rubber finger stall; very nice. She keeps it in a very pretty white frilly bag. Where does she get the money? Audrey, who earns six pounds a week, degree and all, doesn’t like to ask. In any case, Helen very often forgets the symbol of her common sense, and doesn’t take it with her.

Audrey likes men to wear condoms. Helen says it’s because she wishes to be protected not just from disease and babies, but from the man himself; Audrey, says Helen, prefers there to be no real contact. When Helen says things like this they all