KAJITA

KAJITA

Translated by Yui Kajita

PENGUIN BOOK S

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW penguin.co.uk

Kenkaku Shōbai by Shōtarō Ikenami

Original Japanese edition published in 1973 by SHINCHOSHA Publishing Co., Ltd. First published in Great Britain by Penguin Books 2025 001

Copyright © Ayako Ishizuka, 1973

Translation copyright © Yui Kajita, 2025

English translation rights arranged with SHINCHOSHA Publishing Co., Ltd., Tokyo in care of Tuttle Mori Agency, Inc. Tokyo

The Translator’s Note is not included in the original Japanese edition.

The moral right of the copyright holders has been asserted Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception

Set in 11.5/14.5pt Dante MT Pro Typeset by Six Red Marbles UK, Thetford, Norfolk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISB n : 978– 1– 405– 97576– 6

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

Shōtarō Ikenami (1923–1990) was a bestselling Japanese author famed for his multi-million copy selling series of historical fiction novels. Over his lifetime, he won the Yoshikawa Eiji Literary Award and Naoki Award for popular literature. Over a dozen of his works were adapted for film and television, and his work remains exceptionally popular in Japan.

Yui Kajita is a translator, illustrator and literary scholar, originally from Kyoto, Japan, and currently based in Germany.

Yui Kajita

Shōtarō Ikenami is one of the titans of Japanese historical fiction, and Kenkaku Shobai – widely considered to be his greatest work – balances light- footed entertainment with literary weight, humour with wisdom, and sword-clanging action with the quiet current of the seasons.

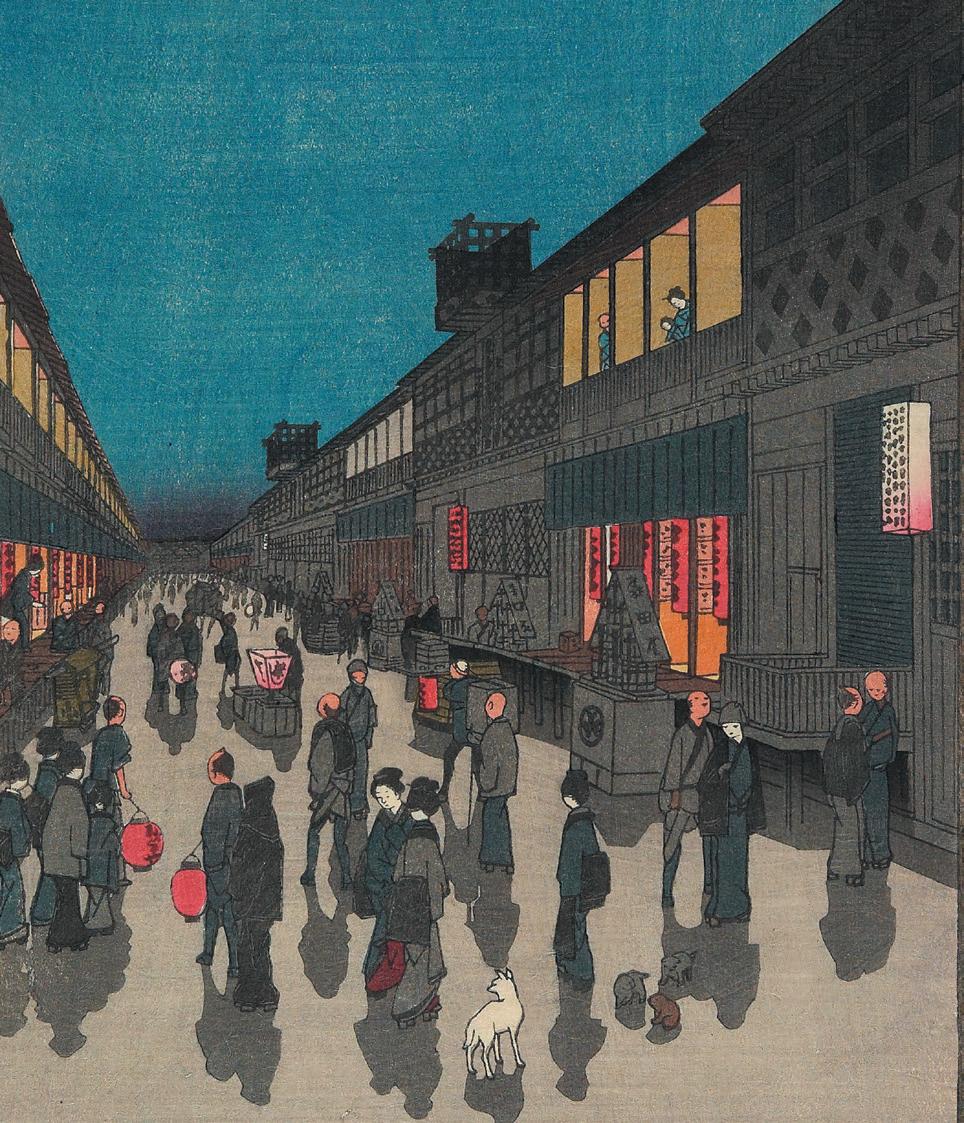

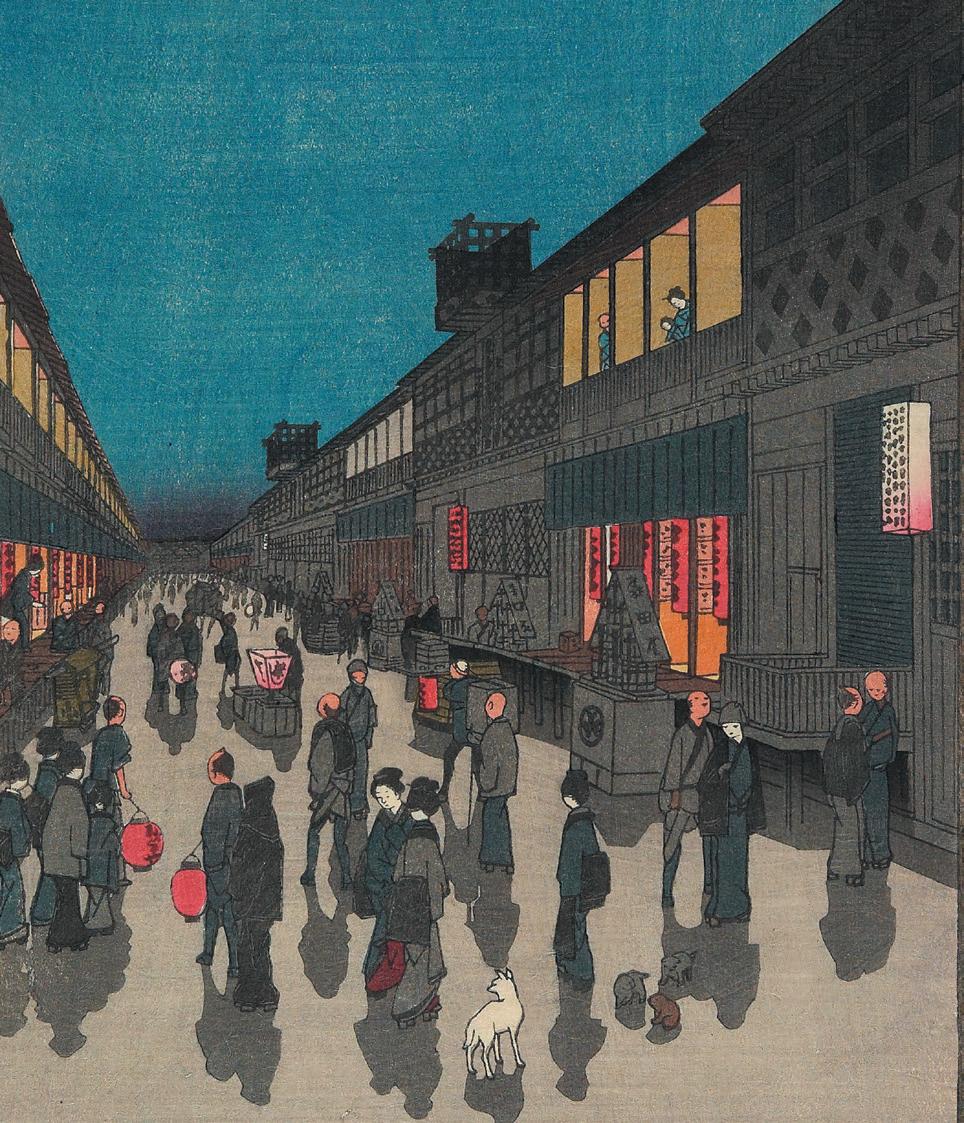

While I hope readers can jump right in and get carried away by Ikenami’s storytelling, there are some basic historical details worth going over in brief. The Tokugawa shogunate , or Edo bakufu, was the military government of Japan established by Tokugawa Ieyasu, which lasted for 264 years (1603–1867): a long era of peace and economic growth after many years of civil war. The Shogun was the de facto ruler of Japan, residing in Edo Castle (in present-day Tokyo), though nominally appointed by the Emperor (a figurehead seated in the Imperial Palace in Kyoto).

In the four-tier hereditary class system of the Edo period, warriors were the ruling class, followed by farmers, artisans and merchants – with an outcast group below the fourth tier which included people with professions that were deemed ‘unclean’. Some of the most powerful members of the warrior class were the daimyo: the 270 or so feudal lords

who controlled most of Japan’s land. Ultimately subordinate to the Shogun, the daimyo were divided into three categories depending on how close their ties were to the Tokugawa family. Hatamoto were high-ranking samurai who served the shogunate directly. Unlike the lower vassals of Tokugawa, daimyo and hatamoto had the right to an audience with the Shogun. Samurai were bound by a strict hierarchy and code of conduct under their lord. A ronin was a masterless samurai.

The status and income of those in the service of the shogunate were measured in rice: koku, a crucial unit, was the amount of rice that could feed one person for a year, equivalent to about 150 kilograms (330 pounds) or five bushels. For instance, a daimyo’s domain was worth at least 10,000 koku, while a ‘greater hatamoto’ had an income between 1,200 and 10,000 koku. Lower down on the social ladder, another level of income mentioned in this novel is forty tawara, or straw bags of rice, which was enough to cover the annual living costs of eight people. Such salaries could be collected in either rice or money.

The ryo was the unit of currency in the form of an oblong gold coin. According to the narrator, ‘Fifty ryo was a considerable sum: in those days, commoners could easily live for five years on that kind of money.’ One ryo was equal to four bu, sixteen shu, or 4,000 mon.

The samurai class were privileged to wear two swords, inserted between the sash-like belt around their waist called obi: a long katana (the blade measuring 27–30 inches long on average, and about 40 inches including the hilt) and a short wakizashi (the blade 12– 24 inches long). Shorter blades,

The Samurai Detectives

such as tanto and kozuka – straight blades in between a dagger and a knife – were also carried for self- defence. A samurai’s formal dress usually included a pair of swords and a hakama (wide trousers worn over the kimono), but Kohei, our protagonist, likes to keep it casual with only his wakizashi, kimono and loose haori jacket. Forging katanas is a fine art, and the swordsmiths mentioned in this novel are notable figures from history.

Chapter 1

Swordswoman

The bamboo grove swayed in the cold wind.

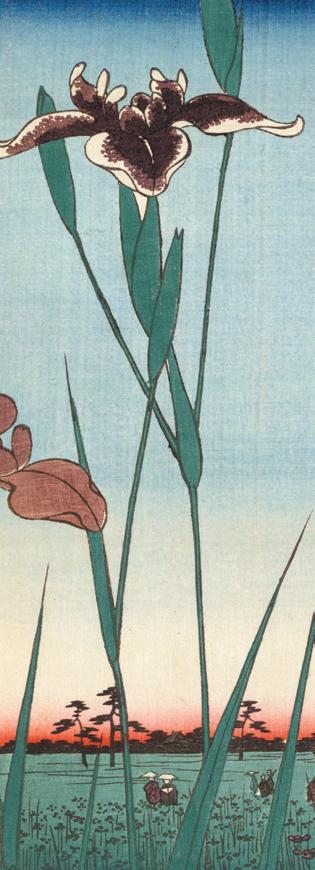

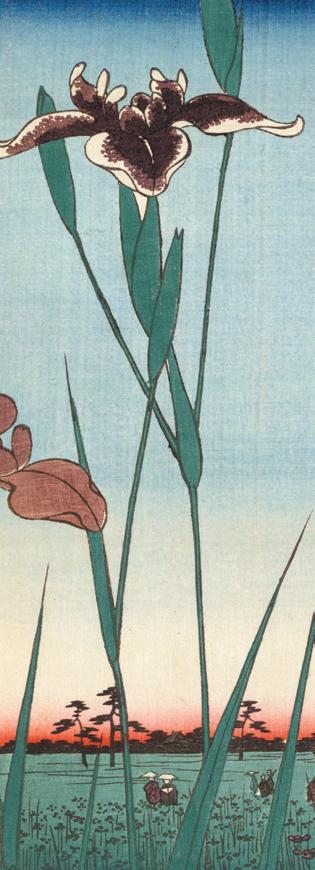

In the western sky, heavy clouds hung low, extending over the rice fields to the distant horizon, the rift between its grey banks tinged with the hazy glow of sunset.

For some time, a flock of northern wrens had been flying around the stone well without a moment’s pause, their liquid trills ringing in the air. The young master of the house watched their flight in total stillness.

His physique was as sturdy as a boulder, but his face, still visible in the gathering dusk, looked younger than his twenty- four years, and his dark skin gleamed like tanned leather stretched taut.

The young man’s eyes glinted with a certain intensity underneath his thick brows. He gazed at the small, nimble wrens flitting about without betraying a hint of boredom.

The smell of broth wafted from the kitchen.

These days, he had been living solely on this simple scallion miso soup, accompanied by a small side dish of pickled daikon, for both breakfast and supper.

The young man’s name was Akiyama Daijiro.

It was nearly half a year since Daijiro had established his own dojo of the Mugai-ryu school of swordsmanship, nestled in the grove of trees near the Masaki Inari-myo shrine on the outskirts of Asakusa, where the river of Arakawa turned into Ohkawa and snaked around the land.

‘Look. From now on, you’ve got to do everything by yourself. I won’t look after you any more.’

That was what his father, Akiyama Kohei, had told him before helping him build a modest dojo of his own. The dojo was about 530 square feet, and Daijiro lived in the two rooms across the hall from it: a six- tatami- mat room of about a hundred square feet and a three-tatami-mat room of about 50 square feet. They were sparsely furnished. The wife of a nearby farmer took care of his meals.

She soon appeared from the kitchen and padded up to the well where Daijiro stood motionless. She gestured to let him know that supper was ready, and then without waiting for a response promptly turned on her heel to go back inside.

The woman was mute.

Daijiro finally went inside.

When he began to eat, his eyes lit up like an artless child’s; his big nose twitched, sniffing the broth in pure delight, and his thick lips seemed to focus their full attention on embracing the freshly cooked barley.

By the time he finished his meal, darkness had already fallen.

So far, not a single pupil had entered his dojo, and the only person who regularly came and went from Daijiro’s

house was the farmer’s wife – but this evening, a rare and mysterious visitor crossed his threshold.

The visitor was a middle- aged samurai in impressive attire, and he introduced himself as Ohgaki Shirobei.

Daijiro had neither seen nor heard of this man before.

Daijiro invited Ohgaki to the larger room and poured a cup of plain hot water for his guest. There was no supply of tea in the house.

At first Ohgaki’s eyes roved over the bare room and Daijiro’s clean yet rather simple clothes, but soon his face split into a broad grin. ‘I witnessed your skill with my own eyes this summer, at Lord Tanuma’s mansion,’ he said.

Daijiro nodded. He recalled the occasion.

This Lord Tanuma was Tanuma Tonomo- no- kami Okitsugu, who belonged to the Council of Elders, or roju: the group of highest-ranking officials under the shogunate. Tanuma had won particular favour with the current tenth shogun, Tokugawa Ieharu, and it was generally acknowledged that his rapidly growing influence outstripped any other’s. This spring, Tanuma received an additional income of 7,000 koku from the Shogun and was appointed as a daimyo ruling over the Sagara domain of Totomi province worth 37,000 koku. Rumour had it that he’d begun as a vassal with a mere 300 koku to his name. It was fair to say that his was an extraordinary rise to power.

In the summer, a sword-fighting tournament had been held in Tanuma’s secondary mansion. About thirty swordsmen tested their skills against each other – some were masters who had their own respectable dojos around the city of Edo, and others were proud representatives from various domains.

It was unprecedented that a young, nameless swordsman like Daijiro was allowed to compete, and yet, on the day of the event, Daijiro defeated seven opponents in a row. Although he lost his eighth match against Mori Kurando – a retainer of Sanada Kou, who ruled Matsushiro of Shinano province worth 100,000 koku – Daijiro was still a dark horse whose remarkable skill became the talk of the day. He had made his debut in the world of swords with flying colours and in the Shogun’s own castle town of Edo, no less.

Daijiro suspected it was thanks to his father that he’d had the chance to appear in this ceremonial tournament.

Now, let us return to the night in question. Ohgaki Shirobei, the unexpected visitor, claimed to have seen Daijiro’s bouts at Tanuma’s tournament.

‘Indeed, your performance was truly admirable,’ the guest went on. There wasn’t a trace of falsehood in his tone.

‘And may I ask what brings you here?’ Daijiro asked quietly.

‘On account of your accomplishment . . .’ Ohgaki leaned in, his knees edging forward on the tatami floor. ‘I would like to request your assistance in a matter.’

‘Yes?’

‘It will be for the good of the people, for the common good.’

‘Hmm . . .?’

‘I ask you to put your excellent skill to good use.’

‘Do you mean a match?’

‘Well, something along those lines . . .’

‘What exactly do you have in mind?’

‘I would like you to strike a certain individual and break both of their arms. Not sever them. Only break their bones.’

‘I don’t follow . . .’

‘If I may be so bold, please . . .’ Ohgaki paused and pulled out a small bundle wrapped in a silk cloth from the fold of his kimono. ‘Here is fifty gold ryo.’

Fifty ryo was a considerable sum: in those days, commoners could easily live for five years on that kind of money.

‘Please consider it.’ Ohgaki bowed, putting his hands on the floor in front of him. ‘I wouldn’t be here if I didn’t have every faith in your abilities. I assure you, it is for the greater good.’

‘Whose arms are you asking me to break, and for what reason?’

‘I . . . I cannot say the name. If you are willing to assist us, we will guide you to the person.’ There was a mole the size of an azuki bean on the tip of Ohgaki’s nose, and he kept rubbing this lump with his little finger as he added, ‘I understand this is not an easy request, but please bear in mind that if you carry out the task with success, you shall soon reap the rewards.’

Despite his rhetoric, Ohgaki flatly refused to divulge any information about the circumstances, the name of the opponent, and the person’s whereabouts. No matter how Daijiro asked him, he remained tight-lipped.

Faced with Ohgaki’s persistence, Daijiro finally drove him away with the words: ‘I must refuse.’

The next day before noon, Daijiro went to his father Kohei’s residence.

From Hashiba, which was just around the corner from Daijiro’s dojo, there were two boats that ferried people across Ohkawa to Terajima. Two farmers were in charge of steering the boats. When one crossed the river and reached the village of Terajima, one could see a footpath that went between the rice fields and, beyond that, a dirt bank that stretched across the landscape. A scene unfolded just as it had once been described in a book: ‘Upon the order of the authorities, three kinds of trees – the peach blossom, the cherry blossom and the willow – were planted on either side of the bank. Ever since, from the month of February to the month of March, the marriage of crimson, amethyst, jade and white amidst their boughs bears a striking resemblance to a curtain of gilded nishiki brocade adorned with delicate embroidery, and the view is aptly praised as profoundly exquisite.’

Places of scenic beauty and historical interest dotted the surroundings – there were the Mokubo-ji temple, the grave of Umewakamaru and Shirahige Myojin shrine, to name a few – and each season offered different shades of picturesque charm. Six years had already passed since Kohei had settled down in this neighbourhood.

To reach Kohei’s residence, one followed the bank’s path to the north. The house stood in front of a pine grove in the middle of rice fields overlooking Kanegafuchi, where

the three rivers of Ohkawa, Arakawa and Ayasegawa met. It was a small house of three rooms with a straw-thatched roof, which used to be a farmer’s cottage until Kohei bought and refurnished it.

Daijiro turned left off the path, cut across the pine grove and emerged in front of the open engawa, a wooden veranda which adjoined the private living room at the back of the house and looked out on the garden.

He found his father lying on the tatami floor.

If father and son were to stand side by side, Kohei’s white-haired head would go just up to Daijiro’s chest. But that wasn’t because Daijiro was especially tall.

At present, Kohei was stretched out on his side, his head resting on a young woman’s lap as she gently cleaned his ear. She was called Oharu, the second daughter of Iwagoro, a farmer in the nearby Sekiya village. Oharu wasn’t especially tall either, but with Kohei’s head on her lap, she looked like a mother coddling her little boy.

The name Kohei – with ‘Ko’ meaning ‘small’ in Japanese – suited him perfectly.

‘The young master is here,’ Oharu said to Kohei, in a rather casual manner.

‘Mm- hmm,’ Kohei murmured in a mellow voice that belied his years, though he would soon be sixty. His eyes were still closed in dreamy pleasure as Oharu groomed him.

‘Good morning, Father.’ Daijiro, who was neatly dressed in his hakama, greeted his father respectfully.

‘Sit down,’ Kohei said.

‘Yes, sir.’

‘I smell scallion soup.’

‘Really? I don’t smell anything . . .’ Oharu cut in.

‘No, it’s coming from my son,’ Kohei said, reaching out a hand to stroke Oharu, who let out a coquettish squeal. Daijiro looked away.

‘Dai. What do you want?’ Kohei asked.

‘Well . . .’ Daijiro told his father about the strange visitor from the night before.

Daijiro was aware that the only reason a young man like himself – having only returned to Edo at the end of February after a long absence from his father’s home – had been given the opportunity to participate in the tournament and to show what he was capable of before Lord Tanuma and the other high-ranking officials of the shogunate was through the intercessions of his father, who was well connected in many spheres.

And so Daijiro felt obliged to speak to his father about the middle-aged samurai who had appeared at his door with a suspicious request after seeing his performance at the Tanuma mansion, just in case it was anything of significance.

‘Hmm . . . Called himself Ohgaki Shirobei, did he . . .?’

Kohei muttered when he had listened to the whole story.

‘Do you know him?’

‘No.’

‘He was holding a paper lantern from Fujiro in Hashiba . . .’

‘Oho. Sharp eye.’

‘I only saw the mark by chance . . .’

‘I suppose he took a boat from somewhere along Ohkawa, moored at Fujiro and borrowed a lantern there, then made his way to your house.’

‘I think so.’

‘Break someone’s arms, eh . . .?’ ‘Yes.’

‘Oh, how awful,’ Oharu burst out, getting to her feet and pattering away to the kitchen.

Kohei’s head had fallen to the floor from Oharu’s lap, but he stayed where he was, never once opening his eyes.

‘You weren’t moved to accept his bidding for fifty ryo?’ Kohei murmured. ‘He wanted you to break a pair of arms, not chop them off, after all. It makes little difference. If you don’t find a pupil soon, you’ll be hard-pressed to make ends meet. We’ve been living in peace for more than a century now, thanks to the power of the Tokugawa shogun or whatever you want to call it. No war for more than a hundred years. It’s a fine thing. So, Daijiro. In times like these, what the samurai carries on his side – along with his skill in wielding it – becomes another tool for getting along in the world. If you’re not mindful of that, you’ll starve to death.’

Kohei spoke calmly, as if he were mumbling to himself; the son watched his father’s ruddy old face with clear, unblemished eyes.

The warm sunlight of early winter was glimmering on the water that flowed into the garden. The stream was drawn from the river around where it curved at Kanegafuchi, and there was a small boat floating on it. This was Kohei’s boat.

Oharu brought a tray with some tea and sweets and offered it to Daijiro. It was first-rate tea, and the sweets were

the ‘Saga Rakugan’ from Kyomasu-ya, a renowned confectionery shop in Ryogoku Yonezawa.

Daijiro sipped his tea and began to eat the sweets in a leisurely fashion. He appeared carefree, his movements utterly natural; not a whiff of his present life of poverty could be felt in his bearing.

Kohei’s kindly eyelids flicked open, his needle-sharp eyes glinting for just an instant before they were closed again.

‘Thank you for this. I will return now,’ Daijiro said.

‘Uh- huh.’ Kohei nodded. With his little finger, he prodded tenderly at Oharu’s thigh close by his side and said, ‘Take Dai home on the boat, will you?’

‘Sure,’ Oharu said. She went down the garden, hopped on the little boat, picked up the pole and called out, ‘Come, young master.’

‘Thank you for the ride.’ Daijiro gave a courteous response to his father and joined Oharu on the boat.

Since he was young, Kohei had devoted his whole life to the way of the sword, but now he seemed to be savouring his retirement.

Oharu steered with deft manoeuvres even when the boat reached the swirling currents around Kanegafuchi, and the boat entered Ohkawa without any trouble.

‘How old are you again, Oharu?’ Daijiro asked.

‘Nineteen.’

‘So, you’ve been living with my father for two years now . . .’

‘That’s right.’

‘Hmm . . .’

Daijiro thought back to an incident about a month ago,

when his father had made a rare visit to his dojo. ‘You know my maidservant, Oharu . . .’ His father had begun.

‘Yes?’

‘I’m afraid I’ve found myself drawn to her. I don’t have to tell you this, but I shouldn’t keep secrets from you, either. Just letting you know.’

‘Yes, sir . . .’ Daijiro had managed to reply, but his mouth had hung open in bewilderment.

For the last four years, Daijiro had been away from his father, journeying across distant provinces to train himself in body and spirit. So when his father had told him, ‘To tell you the truth, son – these days I’ve come to enjoy women more than swords . . .’ Daijiro was quite astonished.

‘It came to me like a revelation once you’d left, you see,’ his father had continued. ‘I knew then that it was time to close my dojo in Yotsuya and quit the blade.’

Daijiro, who had never really known a woman even now at the age of twenty-four, struggled to understand his father’s words. Until six years ago, his father’s day- to- day life had been more regular; he did frequent the mansions of various daimyos and greater hatamotos, for he had a knack for keeping up friendly relations in society, and he had no need to live frugally, but most of the time, he’d spent his days reading or eagerly training his pupils at his own dojo in Yotsuya Nakamachi.

He’s like a different person now . . .

Daijiro turned his eyes away from Oharu as she guided the boat, swaying from side to side right in front of him.

She laughed happily.

That evening, Kohei asked Oharu to take him out on the boat and crossed Ohkawa to Hashiba. It wasn’t to visit his son’s dojo. He was headed for Fujiro, an elegant restaurant in Hashiba.

Though he was dressed informally without a hakama over his kimono, Kohei had donned a fine haori jacket and casually thrust a short sword into the obi around his waist – this wakizashi had been forged by Horikawa Kunihiro and measured nearly eighteen inches – and his white hair, which Oharu had smoothed down, looked neat and smart.

He stepped on to Fujiro’s small wooden pier and said, ‘Wait for me at home, Oharu.’

She nodded with a smile and glided back over the river and into darkness.

Kohei went through to a small private room at the back of Fujiro, ordered some sake and called Omoto, whose job was to entertain the guests. Kohei was a regular at Fujiro, so he knew her well.

‘I hear you’ve been working hard these days, sensei,’ Omoto greeted him with an arch smile.

‘Doing what?’ Kohei asked.

‘Why, they say you’ve been strolling around Mokubo-ji holding hands with a girl who looks so young she could be your granddaughter.’

‘Uh-huh.’

‘How are you faring?’

‘I’ll have a hard time keeping up with her soon. The girl learns fast.’

‘Oh, sensei . . .’

‘Jokes aside . . .’ Kohei paused, pinched out a small gold piece worth half a ryo and tucked it into the collar of Omoto’s kimono. ‘I want to ask you something.’

‘What is it . . .?’

‘Last night. A samurai came here – a portly fellow of about forty with a mole the size of an azuki bean on the tip of his nose – yes?’

‘Gosh, how did you know?’

‘Where is he from?’

‘I have no idea. It was his first visit here. He came by boat from Oumi-ya, the boathouse outside the gate by Asakusa bridge – he just had a spot of sake, then he went out for about half an hour and came back again . . .’

‘To return the lantern he borrowed?’

‘Why, yes!’

‘And after that?’

‘He went back the way he came on Oumi-ya’s boat.’

‘Hmm . . .’

‘Is anything the matter?’

‘Oh, nothing . . . Come, pour me some sake, will you? By the way, Omoto – who’s the lucky man who gets to share your company these days?’

‘Naughty, sensei.’

The next day, Kohei had Oharu ferry him to Ume- ya, a boathouse in Hashiba. He switched to a new boat there and went down Ohkawa towards Asakusa bridge. He ordered

the boatman to moor at Oumi-ya, passed through to their guest room and ordered sake. After a short while, he asked for another boat.

On Oumi-ya’s boat, Kohei went back the way he came over Ohkawa. The boatman was a middle-aged man with a stern frown etched on his face that made him seem as though he knew the world inside and out.

Judging that the man actually did know something, Kohei held out a small gold piece to him and said, ‘Do take it.’

‘Much obliged . . .’

‘The night before last, a man of about forty with a mole on the tip of his nose—’

‘Ah, you mean Master Ohyama,’ the man cut in before Kohei could finish.

‘Ohyama . . . was that what he’s called?’

‘Indeed it is.’

‘I was introduced to him some time ago, at someone’s feast, but his name slipped my mind.’

‘He is the steward of Lord Nagai Izumi-no-kami.’

‘Ah . . . of course,’ Kohei said knowingly, his face lighting up.

Nagai Izumi-no-kami Naotsune was a samurai of high rank – a ‘greater hatamoto’ with 5,000 koku in annual income – and he served as the Shogun’s castle guard, among other duties. Although Kohei had acquaintances in numerous circles, he had yet to meet Nagai in person.

Kohei returned home before sunset.

Oharu came out to greet him and said, ‘I popped by at the young master’s place on my way home.’

‘Did you now? What was my boy up to?’

‘I spied him in that room with the wooden floor . . .’

‘The dojo?’

‘Aye. He was standing there all by himself, and he drew his katana . . .’

‘Mm-hmm?’

‘And he just stared at nothing, didn’t move a muscle . . . Oh, it gave me the creeps.’

‘So, he held his katana at the ready and simply stood there . . .’

‘That’s right. He could’ve stayed like that for hours, for all I know.’

‘Hmm . . .’

‘I wonder, is that how he spends his time every day?’

‘Looks like it.’

‘Where’s the fun in that?’

‘That’s the thing with men. While we’re young, we become enthralled even by the smallest things.’

‘Huh.’

‘As for me, nothing’s more thrilling than being here with you.’

‘Ah, that tickles!’

The next morning, Oharu went to see her father, Iwagoro, who lived in Sekiya village and handed him a letter and an errand fee from Kohei.

Iwagoro set out at once.

Iwagoro and his wife, who had no less than eight

children, had been appalled and furious when they had discovered that Kohei was involved with their second daughter, Oharu. But since Kohei had proffered a suitable amount of money in offer for her hand and now took good care of them at every turn, they were delighted.

‘I can’t figure it out, though – how can a tiny old chap like him who knows only how to wave around a sword live it up like he does? Boggles the mind.’ That was what Iwagoro, who wasn’t yet fifty, often said to his wife, Osaki.

Iwagoro delivered the letter from Kohei to Yashichi, the goyokiki in Yotsuya Tenma.

A goyokiki was a private eye of sorts, who worked as a pawn of the Machi-bugyo – the magistrates who maintained order by overseeing the administrative and judicial matters of the area – but the goyokiki’s detective services never went beyond that of an unofficial subordinate.

Now, Yashichi of Yotsuya was still in his thirties, but he had an easy-going, well-seasoned character; his wife ran a restaurant called Musashi-ya, so people in the neighbourhood affectionately called him ‘the Musashi-ya boss’. There were plenty of goyokiki who flaunted the authority of the Shogun and pulled devious tricks behind the scenes, but not Yashichi. Yashichi was a rare specimen, one might say.

As soon as night fell, Yashichi showed up at Kohei’s house, bringing little gifts of fish and vegetables with him. ‘I came to stay the night,’ he said.

‘Thanks for coming all this way,’ Kohei said.

‘Your letter made me anxious. What happened? Please tell me everything.’

Back when Kohei had run his own dojo in Yotsuya,