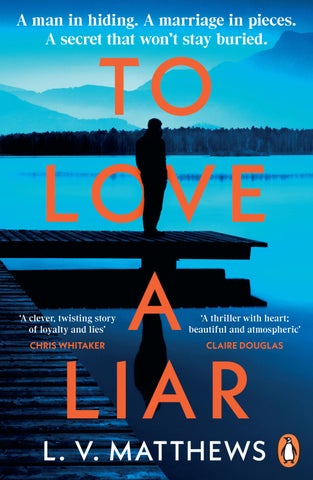

TO LOVE A LIAR

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW

penguin.co.uk

First published 2025 001

Copyright © L. V. Matthews, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception

Set in 12 5/14.75pt Garamond MT

Typeset by Falcon Oast Graphic Art Ltd

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978–1–405–97470–7

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

To my wonderful agent, Camilla Bolton.

On 12 October 2005, police were called to an abandoned council house in Derby, where the body of twenty-fouryear-old Sophia Roy was found on the living-room floor, a needle in her left arm. The needle had administered a fatal dose of heroin, causing a pulmonary oedema, and police and the coroner concluded that Sophia had tragically taken her own life. However, nineteen years on, new evidence has been brought to light, prompting a relaunch of the inquest.

– Observer, article by Caroline Bonner, 3 March 2024

I knew he had something to do with it. I knew it.

– @LeilaRoyPR, X [Sophia Roy’s sister]

At this time, any speculation out there regarding Christopher Fletcher is exactly that – speculation.

– Statement from Jawad Khan, Department of Legal Services, 5 March 2024

They have come to the loch, where it is quiet, where it is wild. They’re here for the inquest, but during the crawling days while they wait, they will try to rebuild their marriage. They need the time together. And Chris needs to hide.

They’re staying in The Old Smoke House, which belongs to Jill’s aunt: a dated eighteenth-century building, stone-built and rendered white with an uneven grey slate roof. It’s on its own, overlooking the loch, among the roots of nature, and a mile from the village. Its remote position should make Chris feel at peace, but the inquest has stripped away any sense of tranquillity. There is an invisible grenade beneath him, close to explosion.

He leans back in the kitchen chair that he’s positioned on the scrub of grass at the back of the house, and stares at the water that leads out to the sea. This is most definitely not a holiday, but at least it is the best time of year to come. Spring in the Highlands is beautiful and fresh and biting. Hopeful. Is that what he’s searching for out here? Hope? Perhaps it is. Or perhaps it’s closure he wants.

Neither he nor Jill wanted to leave the safety of their house in Sardinia, but the coroner called for it and so they came, along with Jackson, their Great Dane, who now lies at Chris’s feet in half-slumber. Chris is glad they brought him over. It was a long process to get him a passport, and a very long journey in the car cooped up with Jackson’s flatulence, but family is family.

‘What will fate decide for us, Jacko?’ Chris asks. He digs into his coat pocket and throws him a biscuit. Jackson hoovers it immediately, and then stares at the ground, willing for more, like they fall from the sky and not Chris’s jacket.

‘No more treats until dinner. Mum would be cross.’

Jackson puts his head back down. Chris takes the cup of tea that he’s balanced on the thick arm of the chair, the wind snatching away the steam, and watches Jill out on the loch, sailing the dinghy borrowed from her childhood friend. She’s gone far today: sometimes she sails all the way to the mouth of the sea and into the north wind; other times she’ll explore all the little bays and coves along the cliff edges. She’s an adventurer, whereas Chris has never sailed and has never wanted to, even though she’s told him over the years that she’d teach him. He much prefers to watch her from the bank, in awe of how she handles the water. This is the village she grew up in, and its familiarity is why they’ve come – for her comfort, because he owes her that while they wait for the inquest. Wait for the grenade to blow.

Beneath ice-clouds and stormy skies, I sail into tomorrow’s fury.

It feels ironic, this line she’d penned years ago, as if somehow she’d known how their life would end up –caught up in a shitstorm.

She’ll be gone for another hour at least, and in that time he could distract himself by watching a film or making lunch, but these things feel too normal. Besides, he needs to answer the emails he’s been avoiding and force himself to scan social media. The internet searches are narcissistic and self-destructive, but he does them anyway because he needs to be vigilant, and he prefers to do them when Jill

isn’t around because he wants to give her the impression that he’s confident in the justice system, and confident, too, in his own version of events. He wonders if she checks online for his name, or even her own, but in the week they’ve been at The Old Smoke House he’s never once seen her looking at any news websites. Maybe she’s pretending not to care, just as he is. Maybe at night by the fire, she’s got her book open but she’s not reading the words. Maybe her phone is laid in the crease of it and she’s reading all the horrible things about him instead.

He watches her constantly, searching for clues on how she’s feeling, but she’s retreated into her head, writing words in her notebook that she doesn’t want to speak aloud. And who can blame her? Since Caroline Bonner wrote that article, they have moved quietly around each other, all their layers of intimacy gone. He understands it – he’s turned both of their lives upside down – but he misses her; God, he misses the way she snakes her hand around his waist, the way she whispers into his ear, the way she laughs. She’s done none of those things for weeks.

He digs his phone from his pocket, and goes first to X, typing in the hashtag: #sophiaroy

Reams of chat come up and he painfully starts to sift through, like a panner in a river looking for nuggets of truth within the heavy opinion and judgement.

A step closer to the truth . . . How will they get out of this one?

Who takes responsibility?

Who indeed? A question that’s been asked over and over for years, with no clear answers, because that’s how it all operates – in murky light and indiscernible sound.

I can’t believe all the stories coming out about this.

Believe it, he thinks. There is worse to come – always

worse to come. The news about Sophia Roy may well tip the carefully constructed system, but the sole reason for his being here is so he can save it.

He clicks on his own name, famous now but for the wrong reasons, dissected by the media and by people who weren’t there.

#christopherfletcher #findchrisfletcher

His name is out there, thanks to Sophia Roy’s sister, Leila, but there’s no picture of Chris yet. For how long will he have that luxury, he wonders. He supposes it depends on what comes out at the proceedings. His breath hitches at the thought of it, only a week away now. People will be watching like vultures from all angles. They love wrong moves, and he’s made plenty.

Aggression radiates from the screen and heats his face as he scrolls on and on, until soon it becomes unbearable, and he clicks off and presses the email icon instead. Stacks of emails ping up – from old colleagues, from the legal team – and he starts to battle through them, answers some, deletes plenty. On and on until his fingers start to shake. Perhaps they were already shaking to begin with.

The image of Sophia Roy seeps into his mind, weighing him down like lead. He closes his eyes, exhausted.

‘Chris?’

His eyes snap open. The sun has moved, and Jill is standing in the boat, twenty yards away, with the rope in her hand. He hurriedly shoves his phone, which is loose in his hand, back into his pocket.

‘Did you turn the boat back around?’

‘What? It’s midday,’ she says, glancing at her watch. ‘I’m always back for lunch.’

He chastises himself. It was a mistake to be outside; he cannot afford to lose himself in sleep or whatever distorted state he was just in, even if the chair is sheltered from view.

Jill steps on to the bank, takes off the life jacket, and then bends to haul the boat slightly out of the water and on to a smooth rock, where it will wait until the next time she uses it.

‘Any news from Jawad?’ she asks.

Jawad is his legal representative – young but energetic and efficient.

‘Nothing of importance. A few things to read.’

She ties the rope to a jutted stone. ‘Do you want tea?’

He touches the mug on the arm of his chair and finds it stone cold. ‘I – yeah. Thanks. How was the water?’

‘Great. Some beautiful birds.’

‘Oh.’

‘Yeah.’

‘Great.’

‘Yes.’

When did they become a couple that talked about birds? But then, when did they become this age, late forties? He’s spent too much time reflecting on the past and missed the present.

She walks towards him, puts out her hand for the mug.

‘I love you,’ he says.

She doesn’t answer, looks out to the loch again. Strands of hair sweep across her face with the wind.

‘What? What are you thinking?’ he asks.

‘It’s my birthday tomorrow.’

He swallows, had forgotten. With everything going on, the days have melted into one another and he’s lost track of the date. He’s never forgotten in all the years they’ve

been together. He always tried to be at home with her too, even if it was for just a precious couple of hours.

‘Yeah,’ he says hurriedly. ‘My plan was to cook you something nice.’

She nods, but her face is neutral. Possibly because she can tell he’s lying, possibly because he is, in fact, a bad cook and she’s not at all excited by this prospect. Possibly because she doesn’t want to be here, even though this is her aunt Meredith’s place, and the village of Jill’s childhood.

‘We’d usually be in Marco’s,’ she says.

‘I know.’

Marco’s is their local restaurant back in the town of Palau. They go there most weekends, and always for birthdays. Marco and his family have become their family too. When everyone else leaves the restaurant on a Friday night, Chris and Jill go walking to the beach with Marco and Angela, his wife. Together they paddle in the silver waves and share a bottle of wine.

‘What about if we went out tonight?’ Jill says suddenly. Chris frowns, confused. ‘Out where?’

‘I don’t know. The pub?’

He laughs. ‘Good one.’

But she’s not smiling. ‘Is it so stupid?’

‘You want to go to Harris’s?’

Harris McGowan owns The Black Horse and is an old schoolfriend of Jill’s.

‘Maybe it’s stupid, but . . . I don’t know. I’m beginning to feel like a lab rat.’

He tries not to let his frustration spill over into his voice. How could she be suggesting this, given the severity of the situation?

‘We can’t go out, Jill.’

‘We’ve gone to the shops.’

‘You’ve gone to the shops. People know you’re here. No one knows I’m here.’

‘Meredith knows.’

‘Apart from Meredith.’

‘And Harris.’

He blinks. ‘What?’

She puts her hands on her hips, a gesture of confrontation. ‘Harris asked me about the inquest, and I told him you were here. I couldn’t lie to him, Chris.’

‘You could have tried,’ he says, and attempts not to seethe.

‘He’s my best friend.’

Chris goes to speak – isn’t he supposed to be her best friend? But a best friend would never have been as deceitful as he has. He swallows his hurt and reaches for her.

‘OK, I understand. That’s OK. But we agreed you’d keep a low profile, yes? Susie’s for food, and Harris because you borrowed the boat.’

She doesn’t say anything.

‘Shall we watch a film tonight? Armageddon?’ He pauses, smiles. ‘Too ironic?’

She glowers at him.

‘We need to wait until all this blows over,’ he says. ‘You know that. We’re doing fine here in Smoke House.’

‘I feel like a fugitive, hiding away like this.’

‘It’s not a fucking holiday,’ he snaps, and then feels bad. She looks like she’s going to say something, but doesn’t, and he’s grateful. He reaches for her again, his fingertips grazing her hip.

‘Look, I’m sorry, but we can’t – we’re here for the inquest. I can’t . . .’

‘What if we went in the back way?’ she says. ‘And stayed in the back room? No one goes in there much anyway. What if I text Harris and ask him how busy it is?’

‘Jill—’

She purses her lips and then nods reluctantly. ‘No, OK. I know, I know.’

‘We’ve been so careful. Let’s not upset it all now. When the inquest is over and everything is done – we can go for a drink, then.’

She looks him straight in the eyes. Her skin has tanned with the sailing, and her eyes are a brighter blue as a result. ‘What if it doesn’t go the way you want it to?’ she says.

‘What are you talking about? It’s just going to be a few questions. Clarifications.’

‘Fine.’

She turns away from him, but he catches her expression and she looks so sad that it pulls at his heart. He feels terrible; he’s done this to her, upended everything she thought was true. Jillian is his rock, his support, his everything, and he hasn’t even bought her a sodding birthday card.

She goes to walk away and he catches her arm.

‘You believe that, right? That it’s all going to be OK?’

‘Yes,’ she says, and she smiles, but it’s thin and tight.

‘Text Harris.’ He says it before he’s even realized. ‘And if it’s not busy, we’ll go for one and sit in the back room.’

Her eyes light up. ‘Really?’

His heart rate is spiking, but he ignores it. He takes her hands in his, notes the warmth of them, notes the longing in his chest for the emotional warmth of her, which has long been absent.

‘It’s your birthday,’ he says.

They walk the twenty minutes to The Black Horse but leave Jackson at home because he is huge and will draw attention. They haven’t needed to pass through the village itself because The Black Horse is set further out, the only building looking out over the small fishing harbour, and for that mercy, Chris is thankful.

They walk through the big pub garden and open the back door. Chris is relieved to see the room is empty. He can hear laughter coming from the main bar, wonders how many people are in there and who it is. They shouldn’t be here. It feels so wrong. He forces himself to smile reassuringly at Jill, but she doesn’t smile back. She looks decidedly worried.

He squeezes her hand. ‘Are you OK?’

‘I’m being selfish.’

‘No, look, I promised you one, and we’re here now.’

She’s nervous, shifting on her feet like a skittish horse and picking at the skin around her fingernails.

‘Hey,’ he says gently. ‘Don’t do that. They’ll bleed.’

She nods and stops, but she’ll start up again, he knows she will. It’s a habit she’s always had, a tic exacerbated by stress, and this is probably the most stressed she’s ever been. In the last few days he’s noticed that she’s been binding her hands in bandages when she goes out to sail because the salt in the water hurts like hell against the rawness of her fingers. Again, he’s done this to her – hurt her physically as well as emotionally. He knows that she sails to be away from him, to have her own time and headspace, and he gets it; the pressure of keeping everything lidded is exhausting for them both.

He spots a table that faces the doorway to the main bar. He can see who comes in from here and can adjust himself

accordingly. He’s wearing a cap – not for fashion; it’s too young for him – but he doesn’t dare remove it.

‘I’ll take the table there,’ he says. ‘You go to the bar.’

She nods, makes to walk out, but a voice stops her.

‘You came.’

Chris glances up and sees Harris in the doorframe. He’s a tall, wiry man, wind-burnt and with a mass of black hair like a bird’s nest on his head. Chris hasn’t seen him in a long while, but he looks the same, albeit with a few more lines on his face.

Harris walks towards them, holds out his hand. ‘Good to see you both.’

Chris half stands to shake it. ‘And you, Harris.’

‘Everything OK?’

‘We’re doing all right,’ Jill says tightly. ‘We thought we’d come out for a drink.’

‘Aye. Your message was a bit of a surprise.’

Yes, thinks Chris. They are inviting trouble. If Oliver knew what they were doing, he’d blow his top.

‘It’s Jill’s birthday tomorrow,’ Chris says.

Harris smiles at Jill. ‘I remember. You’ll have a drink on the house, both of you.’

‘Thanks, Harris,’ she says.

‘Who’s in the bar?’ Chris asks.

‘Two couples from the next-door village – old – and some of Lorna’s friends at the bar. They’ll give you no issue.’

Lorna, his daughter, sixteen now. She is Jill’s goddaughter, though Chris has never even met her.

‘Usual?’ Harris asks.

‘Please,’ Jill says.

‘I’ll take a half of Tennent’s,’ Chris says at the same time.

‘I’ll bring them through myself.’ Harris looks at Jill. ‘You’ve got good weather for the boat, Jillian.’

‘It’s a salvation.’

The word stings in Chris’s ears, whether deliberate or not.

‘Do you want to come fishing with me sometime?’ Harris asks her.

‘Doubt we’d catch another tope, like last summer.’

They laugh together, and Chris is momentarily jealous of the connection between them, and the ease that comes from years of uncomplicated friendship. He’s jealous, too, of the fact that she’s been able to maintain this friendship. She returns every year, stays at Meredith’s house, but this is the first time Chris has been back in the UK for nearly two decades. He has missed so much, so many people and events, because of what happened. Everything balanced on a knife edge. A lump of grief forms in his throat – he missed his parents’ funerals, for fuck’s sake.

He smiles, tries to join in. ‘You caught a shark?’

‘Aye. We let it back in, didn’t we? It wasn’t for the table.’

‘It was a beauty,’ Jill says.

‘There’s a storm due in the next few days, but we’ll just keep an eye on the weather. Are you eating tonight? I can recommend the bream.’

Chris shakes his head. ‘No, a quick drink—’

But Jill nods, enthusiastically. ‘Can we take a look at some menus?’

Chris stares at her. He’d agreed to one drink, and now she’s playing happy families.

‘Aye, I’ll get some. I’ll tell anyone else coming in that the back room isn’t available tonight.’

Chris shifts and Harris leaves the room.

‘I’m glad we came,’ Jill says. ‘Are you?’

Chris leans so he can see into the main room, sees someone’s arm on a chair by the fireplace.

‘Chris? It feels normal, doesn’t it? Like when we used to come here together. It was so long ago, wasn’t it? Do you remember? Twenty years ago or something? When Kate ran that Easter hunt and Cal’s dogs ate all the eggs? When Duncan fell into the water?’

She smiles again, but this time he doesn’t. How can he explain to her that he doesn’t feel normal? That every day since 2005 he’s been looking over his shoulder? He doesn’t remember the eggs, doesn’t seem to remember anything from that long-ago life except for the frightening scenes that loop over and catch him unawares in the strangest of places.

‘Chris?’

‘What?’

‘This is nice. Isn’t it? Being out.’

He smiles, and she must see the effort it takes to do so because, for a brief moment, she looks hurt, but now she is distracted, looking at her bag and taking her phone out of it.

‘Meredith is calling me.’

‘Don’t answer it,’ he says. ‘Let’s try to have a nice time without your aged aunt putting a flea in your ear.’

‘It’s probably about my birthday.’

‘Can you call her back?’

‘Why? Because we’re having such a great time?’ she says sarcastically.

She is shifting sand, veering from extreme anger to upset to blame and back again. He can’t say anything to make it better.

She puts the phone away again, sighs. ‘You’re right. Sorry. It just feels odd being here.’

‘I thought you said it felt normal?’

‘Well, I was lying. It doesn’t.’

‘Happy birthday,’ he says, also sarcastic, but gentle, like a peace offering, a joke. He holds out his hands across the table for her to meet them. He doesn’t want to fight.

She takes his hands in hers but doesn’t say anything. They sit there, the lighting low and ambient, the paint dark grey and flaking on the walls. There is a large frame of fisher man’s knots above them, and a sailing boat lantern on the sill, a thick candle alight within. Even from inside, he can hear the boats outside, sails chiming like bells. In any other circumstance, it would be good to be here. He looks across at Jill, at the rope of blonde hair tied unfussily in a simple French plait over one shoulder. Effortless beauty.

‘I didn’t get you a present,’ he admits. ‘Or a card.’

‘You don’t need to. I’m forty-seven.’

‘But I’m sorry. Everything just . . .’

‘It’s fine. I appreciate this, coming to the pub. I appreciate feeling important.’

He baulks internally at her last sentence – a barb because of everything he’s putting her through.

‘Oh!’ a voice exclaims above them.

Startled, Chris looks up and sees a girl who has come through, dressed in black jeans and a yellow hoodie, her dark hair in a choppy bob. She’s followed immediately by Harris.

‘Lorna! I said I was shutting the area.’

‘I know,’ the girl replies. ‘You just said. I was coming to shut it up for you. I didn’t know that Jill and . . .’

There’s an awkward pause. Jill is wringing her hands.

Chris’s heart is beating fast. ‘It’s no problem,’ he says, even though it is.

Lorna looks at Harris and then at Jill. ‘Is this . . .’

‘I’m Chris,’ Chris says at the same time. Resigned, because of course she’ll work it out.

Harris puts the drinks down. ‘But no one needs to know he’s here, understand? Get the menus.’

She leaves.

‘I’m sorry,’ Harris says.

‘She was trying to help you. It’s OK.’ But Chris’s voice is wooden and everyone hears that it’s not OK.

‘She’ll know all the things about you are nonsense.’

Chris blinks. ‘You think she’ll be following it?’

Jill makes a face at him. ‘Everyone is following it. You think I’ve been skipping around the village and no one has asked me about you?’

Harris walks away swiftly.

‘I didn’t know you’d been skipping around the village,’ Chris says in a low whisper.

‘A figure of speech—’

‘So Harris knows I’m here, which we didn’t agree to, and now Lorna.’

Jill bites at her finger as Lorna returns.

‘Hello, Lorna,’ Jill says, her voice now a bright singsong. ‘So how are you?’

‘Umm. I’m OK.’

‘How’s school? Are you studying for Highers?’

‘Umm. Yeah. I started college last September.’

Chris is only half listening to their exchange, has one eye on the door behind Lorna. Harris has disappeared from view. Some of the younger group from the bar – Lorna’s

friends – have moved into his eyeline. He looks away quickly and to Jill. She catches his eye.

‘Are you OK?’ she says.

‘I—’

She looks over his shoulder, realizes what he’s seen.

Three teenagers are hovering at the doorframe.

Lorna looks up then, frowns at the doorway. ‘Go away,’ she says, crossly, and shuts the door. She looks then to Chris and Jill. ‘Sorry.’

Jill turns to Chris. ‘Maybe we should go?’

Chris smiles tightly at her, feels it come out as a grimace. Every inch of him screams to get up and go.

‘It’s fine,’ he says.

Please, he thinks. Please let it all be fine.

‘Let’s eat something that’s not cooked by you.’

‘I’m a great cook,’ Jill says, indignant.

‘I know you are,’ he says. ‘But I’m shit.’

She gives a half-smile. ‘You are shit.’

‘Guilty.’ He laughs, and then stops abruptly.

Jill stares at him.

Chris clears his throat. ‘I’ll have the pork, Lorna. Please.’

Lorna nods, her eyes down at the pad in her hand.

‘And I’ll have the bream,’ Jill says.

‘They both come with new potatoes and greens. Is that OK?’

‘Perfect.’ Jill hands the menus back over. ‘Thanks, darling.’

Lorna looks like she can’t get away fast enough.

‘You might want to stop declaring yourself “guilty”,’ says Jill as Lorna closes the door behind her. ‘It’s not a good look.’

‘It was a slip.’

‘Wasn’t it just?’

Jill finishes her pint quickly, starts to tap her foot against the table. They sit in silence.

‘Meredith is calling again,’ Jill says after a moment, her phone in her hand.

He drinks, the cold liquid soothing the ache beginning in his head. ‘Ignore it.’

‘I shouldn’t—’

‘She’ll text you if it’s important.’

‘She’s just texted.’

He sighs. ‘What is it then?’

She doesn’t answer him, is tapping on the screen, and then her hand flies to her mouth in horror.

‘What?’ he says. ‘What is it?’

She turns the phone around and the screen shows a picture of him – here at the pub – on social media, posted four minutes ago by an anonymous user.

#murdererattheloch #ourownlochnessmonster #justice forsophia #christopherfletcher

It’s all coming out of the woodwork. The great unmasking continues. #sophiaroy #justiceforsophia #christopher fletcher #nowheretohide – @Outtahere, X

Is that him?? Have you got a better photo? Where is this?? #sophiaroy #justiceforsophia #chrisfletcher #christopher fletcher #nowheretohide – @MMOP, X

Someone’s having a laugh. That’s not him. – @MinnieMoose, X

Where are you guys looking? I can’t find any photo? – @bemorelauren, X

There’s going to be an inquest, remember. Innocent until proven guilty. #sophiaroy #chrisfletcher – @booyakka, X

Inquests are legal inquiries into the cause and circumstances of a death, and are limited, fact-finding inquiries; a Coroner will consider both oral and written evidence throughout the course of an inquest. The purpose of the inquest is to find out who the deceased person was and how, when and where they died, and to provide the

details needed for their death to be registered. It is not a trial.

– www.cps.gov.uk

They leave the pub, leave the drinks on the table. Chris locks Jill’s hand in his, pulls her forward. Outside in the dark she fumbles to turn on the torch and he snatches it from out of her hand.

‘No,’ he says. ‘They can’t have any more pictures of us. People will know where we’re staying because you always stay at Meredith’s. And they’ll have seen you out in Harris’s boat.’

In the blackness, they half jog down the lane and across the field, down the grassy hill to the lone house, but with every step, he feels more and more disconnected, fuzzy. He keeps telling himself over and over that it was only a profile shot, and that he’s changed from all those years ago. He is wearing the cap. But he can’t erase the essence of himself. What if someone recognizes him? What if the person who took the photograph is going to betray their location? He needs to call Oliver.

They get home within fifteen minutes and shut the door, stand in the stillness and the dark, their breath short and panicky. Jackson stands to greet them, but they don’t touch him yet, keep their arms around each other, and for a moment, he absurdly thinks how nice this is – that they’re embracing, that he can feel her heart thumping against her ribcage. But it’s for all the wrong reasons.

‘I’m sorry,’ she says into his chest. ‘I’ve fucked it all up.’

‘You’ve not done anything.’

‘I did, Chris. I made us go there. Was it one of those kids? One of Lorna’s friends?’

‘I think it must have been.’

She sobs into him until his shirt is soaked through. ‘I’m sorry,’ she says.

‘I’m sorry.’

Because he is. For everything.

Time passes, and no one has come to hunt them – no lanterns and pitchforks. Jill stands back to look up at him.

‘Why did you stay?’ he asks quietly. ‘After all I put you through over the years?’

‘Because I love you, fool.’

Love. It is the reason for all great things but also the reason for the bad. The things Chris has done to hurt Jill are insurmountable.

‘I need to make a phone call,’ he says, heading for the spare bedroom and shutting the door.

Chris watches Jill in bed, asleep now beside him, the silver light of the moon picking out the curve of her cheek, her long eyelashes.

He shouldn’t have listened to her when she suggested going to the pub; they had been doing so well to keep his presence here a secret. The photo has now gone –dealt with by Oliver – but it’s still on someone’s phone and there’s nothing he can do about it coming back online again, over and over. And asking Lorna which of them took the photograph would only fan flames. Perhaps Lorna herself asked her friends to take it.

He clenches his jaw.

He is too angry to sleep. He swings himself out of bed, grabs his dressing gown from the back of the door

and goes downstairs. The wooden staircase creaks with his footsteps, but he doubts Jill will wake. He suddenly slams his fist on the wooden bannister, and the thud of it is like a crack of lightning in his ears. He wants to roar, tear everything up, but he must seethe in the silence, as he always has done. He’s a man used to violence, but against the power of the internet and this unbending campaign to crush him, he is powerless.

He goes into the snug, doesn’t bother turning on the light. Sitting on the arm of the sofa, he stares out of the window at the loch. The public don’t know, he thinks bitterly. No one knows the whole truth. No one but him, and the others who lived through the same thing he did, can possibly understand the nuances of it all. Nobody wants to hear about those, though, or the context out of which all this was born, because everyone loves to hate the ‘villain’.

There’s a creak on the stairs, followed by Jill’s voice. ‘Chris?’

He doesn’t want to answer her, even though it’s technically now her birthday and it feels mean not to. He wants to hide away from her, from the world, because he is so angry, so lonely, and upset. Yes, upset, because of Sophia, of what happened to her. But he can’t share that particular pain, and especially not with Jill.

He moves swiftly so he’s behind the door and out of sight as he hears Jill moving in the kitchen.

‘Chris? Are you down here?’

She sounds timid, nervous. He can tell that she’s seeking his assurance, security, and yet he doesn’t give it to her. He stays quiet, listens as her footsteps approach, and then feels her presence in the snug, even though he can’t see her. He catches the faint scent of her: a rich citrus from the oil

she put in her bath after they returned. And then he sees her silhouette, sees the turn of her head as she looks this way and that in the gloom. But even if she switches on the light, she’ll not see him here, behind the door.

‘Chris?’

Perhaps she’ll think he’s gone for a walk. Perhaps she’ll think he’s in the downstairs bathroom. He hears her go back up again and he exhales into the darkness.

He was always good at hiding. As a boy he was obsessed with spy-novel heroes and true-life spies – encouraged by his dad, of course – and Chris would skulk around the house pretending to be one, hiding behind doors and under beds. He heard a lot of things that way – conversations between his parents that he shouldn’t have been privy to, conversations his parents had with their friends. Teachers in their staffroom when the door was ajar. He wrote down all he heard in his black book (like all good spies did). Sometimes he repeated things back to them months later in an attempt to impress, like he was a mindreader, a fortune-teller. A superhero.

‘Don’t forget that it’s Uncle Harry’s birthday on Friday.’

‘Is Mrs Reynolds from the school unwell?’

‘The swimming gala is going to be moved to next Saturday. I can feel it in my bones.’

His parents would look at him, amazed at his perceptions, at his observations, laughing when his ‘predictions’ came true. He learnt how to cover himself when they asked how he knew things they thought they’d kept private. Over time the act of lying became addictive. When he met Sophia Roy in 2002, he was an expert in the art because, by then, he’d had professional training in duplicity.

2002

Sophia Roy was late and had missed the talk entirely. An August downpour had snarled up all the roads and people’s tempers; the bus driver had several arguments with people for not making space, and for treading dirt and dog shit all over his bus. She’d decided to get off early when there was a gap in the rain, but it was ill-timed and, in the ten minutes’ walk between the stop and the pub, she got completely soaked. Droplets ran down her hair and her bare arms and stuck her thin cotton dress to her skin. She had no umbrella but couldn’t have held one anyway, thanks to the pot plant balanced carefully in the crook of one arm. No matter. She had arrived at the pub eventually, stepped into the fug and the noise and the buzz. Soho pubs, indeed the district itself, had their own particular energy, she thought. People full of burning ambition, desire, ideas. Full of idealism. And she was no different.

Cigarette smoke curled down the staircase as she walked up it, her wet trainers squeaking on the tread. She could hear Jude’s laugh, a distinctive bark, from above, and then she was there – with her people. Carlotta and Paul were on the sofa, engaged in conversation, Jude and Johann were carrying beers from the bar to a table, and Esme, Peter and Jodie moving chairs to accommodate everyone. There were a few others she didn’t recognize, and that

was good: it meant that they were starting to make headway with their messaging. People were interested in what they were saying, attracted to the same ideology that had drawn her to Green is Go. That together they could make a difference to the world.

‘Look who it is!’ Johann called when he saw her across the room.

She smiled, held the plant aloft.

‘Get yourself a drink,’ he said. ‘I put fifty pounds behind the bar.’

She nodded. She liked having friends who were older than she was – in Johann’s case, he was twenty years older, and cash rich. There was a level of maturity, naturally, with having older friends, but there was also such diversity within the group, which she loved. Johann was originally from Frankfurt, Carlotta from Milan. Esme was a retired hippy (though still very much a hippy), there were several people who ran their own businesses, a few in the corporate world. Like Sophia, there were students. They had become a family of funny, quirky, good people. She fancied Jude, fancied Evan too. Sometimes Johann, if she was drunk.

She turned to the bar and waited to catch the barman’s eye, but he was busy serving. She put the pot plant up on the ledge, shook her hair of rain and tied it up in a bun.

‘What’s your friend having?’

She turned to see who’d spoken. A young man with dark hair and liquid brown eyes who she’d not met before. He was slender, athletic, wore low-slung jeans.

‘My friend? You mean the plant?’ she said.

‘Yeah, Vera.’

She laughed. ‘You think she looks like a Vera?’

‘Sure,’ he said. ‘Vera the Parlour Palm. See her sprawled across her chaise longue, with her glass of bourbon.’

She was impressed he knew what the plant was – she hadn’t known before looking at the label in the store. Slim stems, feathering leaves. Yes, perhaps she did look like a Vera.

‘Actually,’ she said, ‘she can’t hold her liquor.’

He smiled, then, and it was so nice, so beautifully straight and warm, that she wanted to see it again, immediately.

‘Poor Vera,’ he said. ‘Always the talk of the town after events like this.’

‘Stop. You’re making me not want to give her away. I’m worried Jude will ply her and she’ll fall into ruin.’

‘Who’s Jude?’ he asked.

She pointed. ‘That guy. It’s his birthday tomorrow. Vera is his gift.’

He looked over to Jude, who was still laughing merrily along with others. ‘Ah, hence the singing earlier.’

‘Did I miss that? Oh God, I missed the whole thing,’ she said with a grimace. ‘It was crazy trying to get across town. Were you here for the talk? Was it good?’

‘Actually, yeah.’

She grinned. ‘Actually, yeah?’

‘I mean, don’t test me on it or anything.’ He nodded to the rows of bottles behind the bar. ‘Can I get you something?’

‘I’m in need of a towel, but a Guinness would do.’

He smiled again, this time wider. He had dimples, and she was partial to a dimple.

‘Do you always come to these talks?’ he asked.

‘To every one of them for the last two years. They’re really inspiring.’ She held out a hand. ‘I’m Sophia, by the way. I’m studying Environmental Science at Kingston.’

He took her hand, shook it. ‘I’m Chris.’

‘Are you studying too?’

He shook his head. ‘Nope. I’m a gardener.’

‘That explains how you know my friend here,’ she said, nodding to the pot. ‘You study plants.’

‘I guess I do,’ he said. ‘The pulse of nature.’

A moment passed between them. Something electric and wonderful.

It’s early morning and Jill has been in the snug since dawn, writing. Chris brings her tea at eight, as he usually does, come rain or shine, wherever they are.

‘Happy birthday,’ he says, handing it over.

‘Is it?’ she replies flatly.

His heart sinks. Any warmth and togetherness after everything that happened at the pub last night is clearly now obliterated. Her mood is stark.

‘Do you want to go out?’

She doesn’t look up. ‘I think it’s best we don’t go anywhere.’

Fucking yes, he wants to say. Which is what I tried telling you last night.

But he says nothing, instead tries to read some of her words over her shoulder, but she hunches over the pages. He wonders if they’re about him.

‘A walk in the woods would be OK,’ he says. ‘No one comes this way, do they? You said as much when we got here.’

‘No,’ she says.

‘OK, great—’

‘I mean, no, I don’t want to go out for a walk.’

He waits for a beat, but she still doesn’t look at him. He leaves and goes through to the kitchen, sits at the table. On his phone he flicks to the article written by Caroline Bonner in the Observer, even though he knows it by heart

now. This is what kicked it all off – the piece that threw his careful life into absolute bedlam.

On 12 October 2005, police were called to an abandoned council house in Derby, where the body of twenty-four-year-old Sophia Roy was found on the living-room floor, a needle in her left arm. The needle had administered a fatal dose of heroin, causing a pulmonary oedema, and police and the coroner concluded that Sophia had tragically taken her own life. However, nineteen years on, new evidence has been brought to light, prompting a relaunch of the inquest.

The evidence presented is Sophia Roy’s online journals, recovered earlier this year by her sister, Leila Roy, who, when clearing their family home, found passwords written in an old diary. The online journals date from 2004–2005 and are rumoured to shed significant light on Sophia’s movements prior to her death, and the state of her mental health at that point.

‘What are you doing?’

Chris jumps. ‘Nothing. Did you change your mind about the walk?’

Jill leans over his shoulder. ‘Why do you keep reading it?’ Her voice is clipped. ‘It’s not going to disappear, is it?’

‘I know.’

‘It’s like you want to torture yourself, Chris. And me. It’s like you want to torture me.’

‘No,’ he says, and reaches for her waist.

She moves away, flicks on the kettle and busies herself –loudly – with cupboards and crockery.

‘I’m trying not to think about Sophia Roy. You hear me?’

‘I know, Jill.’

She crashes a spoon on the counter. For someone so graceful, she knows how to make noise.

‘Hey,’ he says. ‘Come here.’

‘I want my life back.’

Chris thinks of their house in the hills – burnt orange walls, white shutters. Tiles on the kitchen floor, thin white curtains. Plants everywhere. Is Marco watering them enough, he wonders. Jill will worry about that. In Palau, Chris is a part-time handyman out there for the locals, cleaning swimming pools, working in the garage. Jill does shifts at the local surgery, writes poetry, teaches sailing and English. Sardinia has become theirs – Jill is with him and they’re a unit, the two of them and Jackson.

‘Please stop reading about her, OK?’ she says. ‘It’s my birthday.’

She pours hot water from the kettle into the mug, clangs the spoon against it, and then pulls open the fridge for milk. How did she finish the first tea so fast?

‘How’s your writing going?’ he asks, awkwardly. He never knows what to ask about it, feels clumsy that he can never offer anything. What should he be asking? How’s your word count? He has no idea.

‘You’ve given me a lot of material,’ she says.

And then she laughs. She laughs and laughs until she cries, bent double and supporting herself with a hand on the back of his chair, and he thinks that, finally, they’re going to be OK, they can weather this together, as they have weathered other things in their lives. But no sooner does she start than she snaps up straight and stops laughing.

‘Over the years, when you were away, I imagined what you were doing, but I never imagined her. I never ever imagined that you would do that to me. To us.’

‘Jill—’