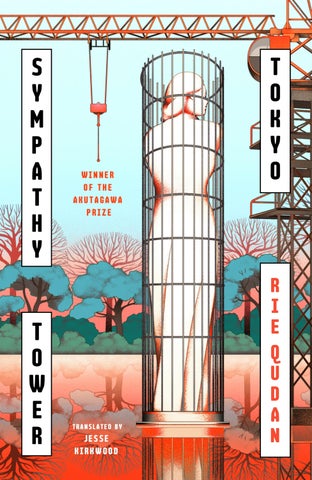

Sympathy Tower Tokyo Rie Qudan

Translated by Jesse Kirkwood

VIKING

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Viking is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published in Japanese by Shinchosha 2024 This edition published by Viking 2025 001

Copyright © Rie Qudan, 2024

Translation copyright © Jesse Kirkwood, 2025

The moral right of the copyright holders has been asserted English translation rights arranged with Shinchosha Publishing Co., Ltd, Tokyo in care of Tuttle-Mori Agency, Inc., Tokyo

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception

Set in 11.5/14.5pt Dante MT Pro Typeset by Jouve (UK ), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

i SB n : 978–1–405–97206–2

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

Translator’s Note

The Japanese language relies on a combination of three distinct writing systems: kanji, hiragana and katakana. A central theme of Sympathy Tower Tokyo concerns the relationship between two of these in particular – kanji and katakana – and the reader may find a brief explanation of their key differences helpful.

Katakana is one of the two phonetic scripts (along with hiragana) in Japanese. It is primarily used for writing foreign words, names, onomatopoeia and scientific terms. Individual katakana characters represent sounds, rather than things or ideas, and visually are simpler and more uniform in structure than kanji. If you want to write ‘coffee’, you write コーヒー [kōhī ], and each of those characters represents an approximation of a sound in the English word.

Kanji, on the other hand, are characters originally borrowed from Chinese, each carrying its own meaning, with pronunciation varying depending on the context. They are often used for nouns, verb stems, adjectives and Japanese proper names. The bad news for any student of Japanese is that they are much more complex visually and require memorization of thousands of characters to achieve fluency.

If you want to write ‘green tea’, you write 緑茶 [ryokucha], where the first character means ‘green’ and the second ‘tea’.

The use of katakana became particularly widespread with the increasing use of foreign loanwords as Japan emerged from semi-isolation in the late nineteenth century. These days, their use is often associated with buzzwords, sales jargon, pop culture and a general desire to make things seem cool, modern, exciting, new. As our protagonist, Sara, notes, katakana-based words combine versatility and vagueness in a way that makes them an attractive choice for anyone wanting to avoid a firm commitment to meaning.

Speaking of Sara, her last name, Machina, is pronounced Makina – itself a plausible enough Japanese name, but one which she has chosen to spell in English with a ‘ch’.

As for the Japanese name eventually given to the titular tower, Tōkyō-to Dōjō-tō, Sara is right to be astonished by the way it rolls off her tongue. The ‘ō’ sounds are drawn out, a bit like the ‘aw’ in the British pronunciation of ‘law’, while the unmarked ‘o’ is more staccato, a bit like the ‘o’ in the British pronunciation of ‘not’. Reading aloud is strongly encouraged.

It would be Babel all over again. Sympathy Tower Tokyo would throw our language into disarray; it would tear the world apart. Not because, dizzy with our architectural prowess, we had reached too close to heaven and enraged the gods, but because we had begun to abuse language, to bend and stretch and break it as we each saw fit, so that before long no one could understand what anyone else was saying. The moment words left our mouths they would become to our listener a baffling tirade. A world ravaged by ranting. The era of the endless monologue.

In the gleaming black tiles of the bathroom where my reflection lurked, I was seeing the future again. Architects can always see the future. It reveals itself to us whether we like it or not.

Sympathy . . . Tower . . . Tokyo?

Of course, as architect, the building’s name wasn’t mine to decide, and whatever my misgivings I was hardly in a position to change it. And yet the moment the high-pressure jet of shower water hit my face, everything about that name

Sympathy Tower Tokyo

– the sound of it, the katakana characters used to approximate the English words, and what those words meant, and all the currents of power swirling around the project – started to bother me, and now there was no going back. Before, it had simply been ‘the Tower’ in my mind, and that had been fine by me. Even after we were invited to

submit a design, we’d been happy, at my firm, to simply refer to it as the ‘Tower’ project. Whatever it ended up being called, however bizarre or controversial the names eventually proposed to the public might be, that would have nothing to do with me. It had already taken shape inside me as the Tower. That was all it could signify. The Tower: nothing more and nothing less. As for its intended purpose, I’d already weighed my options and decided to avoid explicitly backing the project. Entering a design competition didn’t have to mean the architect endorsed the ideas behind it. And yet the moment the Tower became ‘Sympathy Tower Tokyo’ it achieved a texture, a sort of sticky mucosity that I could feel adhering to the furrows of my brain. No amount of water could wash it away. From experience, I knew this to be a very bad sign.

Madness. What is? All of it. Isn’t that going too far? Not far enough. Anyway, are you even allowed to call something ‘madness’ these days? Isn’t that saneism? Let’s just say they have a terrible sense for names, then. Who does? The Japanese people. Whoa, hang on. Isn’t that a bit of a sweeping statement? Fine, then the Stakeholders . . . This was the frantic babble produced by the language- monitoring unit that had whirred automatically into life in my brain, even though it wasn’t like anyone else was getting in there. Exhausted by the presence of the censor that had apparently taken up residence in my head, I felt a sudden, overwhelming desire for equations, for the rush of energy they’d supply. With equations, there was only one right answer. You didn’t have to put yourself in the shoes of each of the numbers and adjust the solution accordingly. I longed for the equality of numbers, the soothing universality

of their language. But there were no equations to be found in the bathroom. All I had for company in here was Sympathy Tower Tokyo and the Tower of Babel and the Stakeholders.

So: why, after thronging together and pooling their considerable wisdom and engaging in what must have been a long and considered discussion, had the Stakeholders settled on a name that sounded like that of a resort chain? Clearly, the very tone in which I was asking this question suggested that I perceived the project in a negative light. Perceived it in a negative light? Come on, let’s be real: my entire being was instinctively screaming no, telling me the tower shouldn’t exist. Every inch of my body was repelled by the incursion of the Sympathy Tower. Ah, I thought, now I know what this reminds me of. It reminds me of rape.

In the white noise of the shower I reassembled memories I’d long thought it unnecessary to retrieve. I had been raped. That was the fact of the matter. A boy much stronger than me had shoved my schoolgirl body down and forced himself on it. And yet the curiosity and desire that young girl felt towards the world – to say nothing of the suppleness of her skin – were so different from that of the middle-aged architect standing here today that to draw a line between them felt like an affront to reality. Plus there was the fact that these days you wouldn’t catch me dead in the bunchedup white socks and loafers I wore back then. Let’s give her another name, then. She liked maths, so we might as well call her Maths Girl. Maths Girl was raped and told people she had been, but the boy who did it and all the people she told decided she hadn’t. The evidence they offered was: that the boy was her boyfriend; that Maths Girl had been in love

Rie Qudan

with him; that it had been Maths Girl who invited him into her house. Simply put, Maths Girl lacked the words to make people see that he’d raped her, and so the accepted truth became that he hadn’t.

In which case it followed that I had no idea how traumatic rape could really be, and no right to liken my situation to it. To do so would be flippant and insensitive towards genuine victims of sexual violence. Still, however inappropriate and hyperbolic it might sound, the fact remained that the woman standing in that hotel bathroom perceived the arrival of Sympathy Tower Tokyo into her life as an assault on her being. If the day came when a man who was not my boyfriend and who I did not love had sex with me against my will, maybe the bodily revulsion I was experiencing now would come to seem completely misplaced. Maybe I’d have to go through something that awful if I ever wanted to claim the right to declare publicly that something felt like ‘an assault on my being’. Maybe becoming a bona fide victim would even provide a compelling and powerful basis for my opposition to Sympathy Tower Tokyo. No, these days I wouldn’t need to go that far. I was an adult now, one who slipped her sockless feet into Italian-made pumps, and I had words and I had wisdom. These days, I would know not to call that boy someone I loved. I would call him a boy I hated, and turn it wasn’t rape into it was, and everything would be all right.

Wouldn’t it?

I’d only been planning on a quick rinse, but my body felt dirty now, and soon I was scrubbing away at my hair, at every inch of my body. At home, showering was a late-night

bone-tired affair in which I simply lathered shower gel on to my skin and washed it away again with all the thoughtfulness of someone washing up dishes, but whenever I stayed at a new hotel it became a conscious act. The showerhead here offered four different spray settings. Later I checked the manufacturer’s webpage and learned that the ‘mist mode’ incorporated a recent technological breakthrough known as Ultrafine Bubbles. Unlike regular showerheads, whose droplets had a diameter of 0.3 millimetres, those equipped with Ultrafine Bubbles produced a ‘never- before- seen’ droplet size of just 0.000001 millimetres. Penetrating deep into the keratinous layer, the unprecedented spray not only washed away impurities from your pores but also boosted moisture retention in your hair and skin.

In the caress of that fine mist I was reminded that the purpose of showering is to purify the flesh – which, when you really get down to it, means unclogging your pores. These days, anyone with a proper sense of personal hygiene knows that ‘brushing your teeth’ isn’t about the act of ‘brushing’ per se so much as the careful scaling of tartar from the enamel. If you want protection against periodontal disease and cavities, you’re better off flossing and removing plaque from your gums than aimlessly scraping a brush back and forth. Our insistence on calling the entire process simply ‘brushing’ is only going to undermine the oral health of future generations, and what’s bad for them is bad for the future. Does this tragic state of affairs persist because the dental industry couldn’t care less about the future, or because it envisions one in which gum disease skyrockets along with its profits? Are there vested interests involved,

and if so which organizations have been weighing in loudest? Incidentally – and here I was addressing my pores – did you even want to be cleaned this deeply in the first place?

Of course, my pores were unable to respond to this absurd question, and so my thoughts turned, once more, to Sympathy Tower Tokyo. Why that name? Why had it been deemed more suitable than any other? And by the time I stepped out of the shower and began towelling myself down, my reckless mind had arrived at another of its sweeping conclusions.

Because the Japanese people are trying to abandon their own language.

They’d been trying for some time, too. In 1958, the new radio tower being built in the capital was officially named Tokyo Tower, using katakana to approximate the English words – a decision that could be traced to a single member of the naming committee, a Japanese person with an apparent aversion to Japanese names. In the public vote, the most popular option had actually been the kanji-based Shōwa-tō, the ‘Showa tower’, after the era it was being built in, followed by Nihon-tō (‘Japan tower’), Heiwa-tō (‘peace tower’), Fuji-tō (‘Mount Fuji tower’), Seiki-no-tō (‘century tower’), Fujimi-tō (‘Mount-Fuji-viewing tower’) – and yet the name eventually chosen was Tōkyō Tawā (‘Tokyo Tower’), ranked thirteenth, simply because the committee member in question insisted it was ‘that or nothing’. Had the tower been named after Showa in line with the public vote, the red-and-white-striped structure may well have struggled to shake the musty associations of that era, which ended in 1989. Instead, these days, the vast majority of Japanese

people had no problem with ‘Tokyo Tower’ – would, in fact, be unable to fathom the possibility of any other name. The committee’s admittedly undemocratic decision may, in retrospect, have been the right one. Democracy doesn’t have the power to predict what will happen. It can’t see the future.

I can see the future.

In hallucinations barely distinguishable from reality I perceive what will one day come to pass. The uninformed might call this a gift or a superpower or artistic inspiration, but really it’s nothing more than an occupational disease. Any architect who’s gone through the process of designing a gigantic structure suffers from it. The bigger your building, and the greater its impact on the cityscape, the more affecting the disease. When you’re conceiving something irreversible you can’t afford to ramble on about how the future isn’t ours to know.

Still, even when an architect turns those hallucinations into drawings, ninety- nine point nine per cent of them remain trapped in the world of two dimensions. If she really wants to change the world she can’t just sit around sketching visions; for her beautiful fantasy to become reality she must be equally skilled in practical matters. The ability to draw up budgets and construction schedules. A readiness to shamelessly sweet-talk the relevant authorities. A flair for convincing even the laypeople that the building should take one particular form and no other. If I lacked any one of these skills, I’d probably earn my living filling gallery walls with pictures instead. But to me, that work wouldn’t be real at all.

‘I do get offers to do solo exhibitions of my drawings, but that’s not where my interest lies. My sketches are no more than an outlet