Richard Coles is a writer, presenter and Church of England clergyman. He is the only vicar in Britain to have had a number-one hit single and appear on Strictly Come Dancing. Reverend Coles is the author of the bestselling Murder Before Evensong mystery.

Professor Cat Jarman is a bioarchaeologist and field archaeologist and the bestselling author of River Kings and The Bone Chests. She is also a historical advisor for museums and an experienced public speaker who frequently shares her expertise on BBC radio, podcasts and TV. Professor Jarman’s research has been covered by print and online news outlets internationally.

Charles Spencer is a journalist, broadcaster and author of historical non-fiction. He is the author of the number-one bestseller memoir A Very Private School and the bestselling histories Blenheim: Battle for Europe, Killers of the King and The White Ship. Charles has also written for numerous publications including Vanity Fair, the Spectator, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London sw 11 7bw penguin.co.uk

First published by Penguin Michael Joseph 2024

Published in Penguin Books 2025 001

Copyright © Richard Coles, Cat Jarman and Charles Spencer, 2024 Chapter illustrations © Inez Skilling

The moral right of the authors have been asserted Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception

Set in Garamond MT

Typeset by Couper Street Type Co. Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d 02 yh 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn : 978–1–405–96658–0

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

The Spanish Flu (CS )

Taking the (Bath) Waters (CJ )

The Death of Lord Kitchener (RC )

Boudicca (CJ )

Two Pair of Pyramids (RC )

The All-But Forgotten Battle (CS )

Guano (CJ )

Ötzi the Iceman (CJ )

The Pilgrimage of Grace (CS )

The Origins of Pasta (CJ )

Wicksteed Park, Kettering (RC )

Alfred’s Pelvis (CJ )

The Panacea Society (RC )

The FANYs (RC )

The Assassination of Sidónio Pais (RC )

Sunbathing (CS )

The Exploding Whale of Oregon (RC )

Cowardice (CS )

Bald’s Leechbook (CJ )

Cosmetics (CS )

The Martyrs of Namugongo (RC )

Crosswords (CS )

Lucca’s Last Levitator (RC )

Female Literary Detectives (CS )

Olga of Kyiv (CJ )

Philip II and His Spanish Armada (CS )

During the Second World War, a German air raid over Oslo caused limited casualties, but a thirty-year-old woman by the name of Astrid was hit by shrapnel, leaving her with a serious wound on the left side of her head. Although she survived, she was partially paralysed and initially unable to speak. When she fi nally did recover her ability to talk, something curious had happened: she spoke with a noticeable German- or French-like accent. Eventually, her case came to the attention of Professor of Neurology Georg Herman MonradKrohn, who described what is now known as foreign accent syndrome (FAS), where the sufferer’s speech is altered as a result of damage to a certain part of the brain. This can be caused by stroke or physical trauma, and cases of the syndrome have been recorded around the world and in a range of languages from Japanese to Korean, from Spanish to Hungarian, and from American-English to British-English. FAS is classed as a rare disorder, with only just over forty cases ever reported.

According to NORD, the US National Organization for Rare Disorders, a medical condition is ‘rare’ if it affects fewer than 200,000 Americans. As such, there are more than 10,000 such diseases in the US and an unknown number worldwide. Yet many are considerably rarer.

In 1880, the French neurologist Jules Cotard described a curious case of what he would later call délire des negations – the delirium of negation. He had observed a forty-three-yearold woman who insisted that she was nothing more than a decomposing body: she said she had no brain, no nerves, no chest, no stomach and no intestines. As she did not consider herself to be alive, she did not even need to eat. Later named Cotard’s syndrome, the illness causes the sufferer to believe themselves to be dead and seems to be a form of psychosis. In a case in Oxford, a brain tumour was shown to be the cause.

Brain anomalies are also the cause of alien hand syndrome. Here, the patient experiences involuntary movements of one hand, in a purposeful rather than a random or uncoordinated way. These movements cannot be controlled, and in severe cases they may be violent: an example includes an eighty-oneyear-old woman who reported being terrified of her left hand because it had repeatedly attempted to choke her and hit her face, neck and shoulder.

Equally frightening is the so-called Alice in Wonderland syndrome (AIWS). Sufferers suddenly fi nd that they observe the sizes of parts of their bodies incorrectly: usually, the head and hands seem disproportionately large or small. The same can be the case for objects around them and the individual also loses a sense of time. Others may experience hallucinations and many have severe migraines. The experiences of

AIWS patients are so similar to what happens to Alice in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland that there has been speculation that Carroll himself suffered from the syndrome. Carroll is known to have suffered severe migraines and British psychiatrist J. Todd, who coined the name of the syndrome in 1955, wrote that it is possible ‘Alice trod the path of a wonderland well known to her creator’. Incidentally, another neurological syndrome may be described in the book: the Mad Hatter’s eccentric and unusual behaviour may have been the result of mercury nitrate poisoning, something hatters used to be prone to because mercury was used in felthat production.

While the causes of many such conditions are unknown, others can be avoided if certain precautions are taken. This is the case for Kuru, or prion disease, which affects the nervous system. Also referred to as laughing sickness, the illness was fi rst reported in a publication in 1957, when it was observed in the Fore tribes of Papua New Guinea. There, Kuru, which means to tremble due to fever or cold in the local language, had been prevalent since the early 1900s, affecting up to 1 per cent of the population. Victims displayed a range of severe symptoms including pain and difficulty with walking and coordination, difficulty swallowing, tremors and muscle jerks, and outbreaks of uncontrollable laughter. The disease is degenerative and deadly, usually within two years. It is no coincidence that the disease was so prevalent among the Fore and in a few other places because Kuru has a very specific cause: it is spread through the consumption of highly infectious brain tissue. Up until the 1960s, Fore groups carried out a funerary practice where they ate the brains of dead people as a form of mourning and respect. As

the disease has an incubation period of up to fifty years, it was still being reported until recently even though the rite is no longer carried out. If you want to avoid it, simply refrain from cannibalism.

Previously categorized as an ‘impulse control disorder’, gambling addiction has been recognized formally as a medical condition only since 1980. Its dangers were noted in the Rig Veda, an ancient Indian Sanskrit text written from 1700 to 1100 bc:

Dice, believe me, are barbed: they prick and they trip, They hurt and torment and cause grievous harm.

To the gambler they are like children’s gifts, sweet as honey, But they turn on the winner in rage and destroy him.

The ancient Greeks gambled with dice, and also astragaloi – the ankle bones of sheep – which were used in Rome and Mesopotamia. Other games were spinning coins, cock fi ghting, quail fi ghting and a game called himanteligmos –described by the second-century Greek scholar Julius Pollux as ‘a certain labyrinthine twisting of a folded strip of leather; upon this one had to chance upon the fold with a peg. If, when the leather strip is unwound, the peg is not caught by the strip [inside the fold], the one who placed the peg loses the game.’

The Romans enjoyed playing latrunculus, and boards for this have been discovered from Britain to the Egypt–Sudan border. We do not know the rules, but it may have been similar to draughts, with dice thrown – interestingly, the dice

were cast down a tower next to the board, to stop anyone influencing how they fell with a cunning use of the hand.

The key gambling fact is, the house always wins. The biggest earners in Nevada – ‘the Silver State’ – are the slot machines, which generated $10 billion in profits in 2022. Penny slots alone generated $3.59 billion: to visualize what that sum means, a stack of those pennies one on the other would trail to the moon and halfway back. Baccarat and blackjack each brought in a further $1 billion, while roulette and craps harvested $450 million apiece from the optimistic.

One of those who, historically, failed to be cowed by the odds was John Montague, the 4th Earl of Sandwich, an English aristocrat who in 1762, so the story goes, was so determined to have no serious interruption during a twentyfour-hour gambling binge that, an astonished Frenchman noted: ‘he had no subsistent but a bit of beef, between two slices of toasted bread, which he ate without ever quitting the game. This new dish grew highly in vogue, during my residence in London.’ This fi rst fast food was, of course, christened the sandwich in honour of the gambling earl.

George Osbaldeston was another betting addict. An excellent all-round sportsman, Osbaldeston was from 1812 to 1818 a Whig MP, but he found that his parliamentary duties came a distant second to his mania for gambling.

Aged forty-seven, Osbaldeston bet a General Charritie £1,000 that he could ride 200 miles in ten hours, using as many horses as he wished. His training for the feat involved galloping sixty miles each morning. The challenge took place at Newmarket, his start and fi nish the Duke’s Stand. Osbaldeston rode twenty-eight horses that day, and successfully completed his wager in eight hours and forty-two minutes (including an hour and a half of stoppages).

He would bet on anything, once putting £50 behind his being able to pull 3,500 glasses of ale within twelve hours, in a Bethnal Green pub. He won that wager, but gambling eventually proved a ruinous pastime. He lost £200,000 in all and had to sell his family estate before dying in poverty in St John’s Wood.

Gambling was long seen as an English obsession, a German visitor in the eighteenth century recalling the fever of excitement at an English cock fight: ‘When it is time to start, the persons appointed to do so bring in the cocks hidden in two sacks, and then everyone begins to shout and wager before the birds are on view. The people, gentle and simple (they sit with no distinction of place) act like madmen and go on raising the odds . . .’

Archie Karas, known in the gambling world as ‘The Greek’, who called himself the ‘king of the gamblers’, arrived in Las Vegas in 1952 with $50. By 1995 he had turned that into $40 million, following an episode known as ‘The Run’.

His fi rst winning streak lasted six months. He borrowed $10,000 from another player, in an establishment called Binion’s Horseshoe, and tripled it in one game. He then went on to win $1.2 million in a pool table bar, where the stakes were $40,000 a game. Karas played the same opponent at poker, amassing $17 million within six months. However, on reaching the high-water mark of $40 million, he lost and lost. He was back to zero within twelve months. He has been excluded from Nevada’s casinos since 2015, accused of marking cards.

Harry Kakavas, an Australian property dealer, turned over A$1.5 billion at a single casino during fifteen months in 2005–6, eventually losing all the A$20 million that was his money in fifteen months. He once lost A$2.3 million

the rabbit hole book in one twenty-eight-minute baccarat session. He sued the casino in Vegas that took most of his money, claiming they should have turned him away because they knew him to be an addict. Even this action, he lost.

In 1925 the architect Sir Clough Williams-Ellis bought the Aber Iâ estate near Penrhyndeudraeth in north Wales. It had cliff s overlooking a sandy estuary, streams, woods, picturesque ruins, ‘a neglected wilderness’, he wrote, ‘long abandoned by those romantics who had realized the unique appeal and possibilities of this favoured promontory but who had been carried away . . . into sorrowful bankruptcy’.

There he started building a village named Portmeirion, an extraordinary effort to create a fantasy Italianate fishing village on the River Dwyryd in what might be described as the munchkin-baroque style. It became famous in the 1960s as the location for the television series The Prisoner, in which Patrick McGoohan played Number 6, a former spy who tried to leave the Service but was abducted and is now held at ‘the Village’, where he attempts to assert the inviolable rights of the individual against corporate power. His frequent attempts to escape are thwarted by a giant white bouncy ball. If this sounds eccentric, his character was not the fi rst unlikely prisoner there. From 1870 to 1917 Aber Iâ was home

to Mrs Adelaide Haig, a devout, if unorthodox, Christian widow, who grew more and more disenchanted with the society of human beings and disgusted with the rapacious character of our species’ treatment of the natural world. She instructed her gardeners not to cut back, prune or trim anything that nature produced and required them instead to send out patrols to seek and detain stray dogs and bring them to the house, which became more and more difficult as it became isolated in the overgrown grounds.

There the dogs assembled in the Mirror Room, where Mrs Haig would preach sermons to them sitting behind a screen in the hope that they too would become devout. Regardless of her success in this enterprise, when the dogs died they were given Christian burials in a cemetery she had created for them, their resting places marked by headstones carved with fulsome inscriptions:

My dear, dear dog gone before To that unknown and silent shore Shall we not meet as heretofore Some summer morning?

You may visit it today with ease, unlike the undertakers who came in a hearse to collect Mrs Haig’s body in 1917 and found the house inaccessible until a mysterious stag appeared on the promontory and led the gardeners, equipped with machetes and saws, through its jungly thickets.

The cemetery continues to be used by bereaved dog lovers, and may be found to the west of the Oriental Lake.

The most splendid pet cemetery in the country, in my view, is found in the former garden of Mr Winbridge, who lived at Victoria Lodge where West Carriage Drive meets the Bayswater Road on the north side of Hyde Park in London.

Here you will fi nd the graves of hundreds of dogs as well as those of some cats, birds and three small monkeys, the beloved pets of London’s high society, which in the 1880s thronged the park serving the smart neighbourhoods of Knightsbridge and Mayfair.

Unfortunately this was extremely dangerous for dogs owing to the number of carriages that circulated there, and under their wheels, and the hooves of the horses that drew them, many met their ends.

‘Darling Dolly – my sunbeam, my consolation, my joy’, reads one, then ‘Dear Impy – Loving and Loved’, my favourite, ‘Alas! Poor Zoe’, and that of the fi rst dog to be buried, ‘Poor Cherry. Died April 28. 1881’. Cherry, a Maltese terrier, belonged to the Lewis-Barned family, descended from a highly respected Jewish banker and philanthropist in Liverpool, whom Mr Winbridge served with ginger beer on hot days. Cherry adored his back garden and when she died of old age the children asked him if she could be buried in her favourite spot. Mr Winbridge agreed.

Perhaps this was a sentimental gesture he came to regret, because the next request for burial was for a royal dog who was run over by a carriage on 29 June 1882. Prince, a Yorkshire terrier, belonged to the actress Louisa Fairbrother, who is remembered mostly for marrying HRH the Duke of Cambridge, cousin of Queen Victoria, without permission, so the match was never properly recognized. ‘Poor Prince’, reads his simple headstone.

That started rather a trend, and Mr Winbridge’s garden, in which he had intended only to bury Cherry, was very much in demand until the cemetery closed in 1903.

You have to make an appointment via the Royal Parks website to visit now, and pay quite a stiff charge, but I highly

recommend it. Look out for the grave of Topper, an obese and disagreeable police dog who was despatched by his owner’s truncheon; Balu, poisoned by ‘a cruel Swiss’ in Berne in 1899; ‘dear little Goofy’; and Ginger Blythe, ‘a King of Pussies’.

At Christmas in 1085, a meeting of the King’s Council was held at Gloucester. William the Conqueror, who, by then, had held England for nearly two decades – was concerned with three particular topics: who were the people who lived in the country, what did they do and own, and how much was their property worth? The answers to these questions, he had come to realize, were key to ensuring he could gather the correct amount of tax, money he sorely needed to fend off the threat of invasion from foreign powers. As a result, William commissioned a survey, later to be known as Domesdei or Domesday, the day of judgement. What has been passed down to us is a remarkable, unique census: Britain’s earliest public record and the most complete surviving account of a pre-industrial society from anywhere in the world.

In 1066, William, a Norman duke, conquered England by defeating the Anglo-Saxon king Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings. The event led to significant changes across the country, not least in terms of land ownership, as William replaced the English landowning elite with Normans, many of whom received land in return for military service. And when the country was threatened by Danes in the 1080s, he needed funds to pay mercenaries. For this reason, he needed to know exactly how much he could demand from his people. A remarkably thorough logistical approach followed. We

believe the survey began mid-January 1086 after England and Wales (Scotland was not under Norman rule) had been divided into seven areas called circuits, each comprising two or more counties. For each, several high-ranking commissioners were assigned to the task of collecting and verifying relevant information that had been gathered by local tenantsin-chief, sheriffs and other officials. To ensure neutrality, the commissioners were not allowed to work in areas where they held land. The exercise was a multilingual affair: William’s men were largely French-speaking lords collecting information from English speakers and recording the information in Latin. Accuracy was ensured through a detailed process. In each administrative region (known as hundreds or wapentakes), jurors were summoned and questioned, under oath, on the veracity of the information collected. Yet it seemed the process was not without drama, as many landholders were keen to take advantage, perhaps exaggerating their claim to land. Many claims and verdicts were challenged. In a record of an inquest in Cambridgeshire, for instance, an unscrupulous sheriff named Picot is described as ‘the hungry lion, the prowling wolf, the crafty fox, the shameless dog’.

By the end, a detailed account was compiled of who owned what: this included how many hides (a standardized unit of land, enough to support a household) there were; how many ploughs (meaning taxable amount of land that could be ploughed by a team of eight oxen); how many men in different social categories (including free men and slaves); the value of the land; and how much of it was woodland, meadow, pasture, mills, or fisheries. To add to this vast amount of data, the same information was recorded for the current year as well as for 1066, the year of the conquest, and for the year William gave the land away. Crucially, this has given us an

extraordinary insight into the social changes that took place with the arrival of the Normans.

In total, 268,984 people are listed, each of whom was the head of a household. Unsurprisingly, the records show that very few women independently held land. Among those who did, one with the greatest holding in 1066 was Gytha, the widow of Earl Godwine of Wessex and the mother of the defeated King Harold. Another was a woman named Asa from Yorkshire, whose lands were disputed in 1086: here, the jurors inform us that the land was independently hers and did not belong to her husband, Bjo˛rnúlfr. When the two separated, she withdrew her possession and kept it herself as a ‘lady’. Yet such women were rare; in fact, one historian has pointed out that there are more pigs listed in the census than women.

Eventually, the returns from all seven circuits were assigned to be written up and collated into one volume, now known as Great Domesday Book, by a single scribe. For reasons unknown, the eastern circuit was never included, and now exists as a separate volume dubbed the Little Domesday Book. While more than 13,000 places are mentioned in the survey, some significant areas were missed out, including London, Winchester, County Durham and Northumberland, again for reasons that are unclear.

The book itself was never intended to be called ‘Domesday’. The name fi rst appeared in the Dialogus de Sacarrio, a book written about the Exchequer around 1176. There, it states that this name was given to it as a metaphor because, like the Last Judgement, the decisions contained within it were unalterable.

When I grew up in Norway, you could pick from two types of cheeses for your open-top sandwich: yellow or brown. Your choice would be cut thinly using a cheese slicer (a Norwegian invention it baffles me that the rest of the world seems to live without) and placed on top of a slice of dark granary bread. The brown cheese was made of goats’ milk, but I didn’t learn until I was much older that this was not what most countries would consider the goats’ cheese norm. Our version, named either brunost or gjetost, is sweet and almost caramel flavoured, and made from the whey that is usually discarded by cheesemakers. But while brunost may be an acquired taste, humans may have produced cheese from goats’ milk for at least as long as they have from that of cows.

Goats were fi rst domesticated around 10,000 years ago, somewhere in the Fertile Crescent, the name given to the region in the Middle East bounded by the Mediterranean and the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. From there, the animals soon appeared in both Europe and Asia, treasured for their hardiness and adaptability to harsh environments as well as for their fresh milk, meat, skin and fibres. The milk would have been used for cheese from an early stage: we know that cheese production from other animals has taken place for at least 8,000 years. Archaeologists have found sieve-like pottery vessels, likely to have been early cheese-strainers,

cheese with evidence of dairy products preserved in the ceramic material.

The Egyptians were certainly fans. During excavations of the tomb of Ptahmes, the mayor of Memphis in the XIX dynasty (thirteenth century bc), archaeologists found a large jar containing a solidified whitish mass once covered with a canvas fabric. When analysed, this turned out to be a cheeselike product made of a combination of cow and goats’ milk.

The Greeks, however, credit the god Aristaeus, son of Apollo and the huntress-nymph Cyrene, with the invention of cheese: he allegedly learned the art of curdling milk from the nymphs. While this particular story must remain unproven, we know from written sources that both the Greeks and Romans used goats’ milk in their cheese production, but often, this was mixed with milk from other animals. While Sicilian cheeses typically contained a mix of sheep and goats’ milk, Phrygian cheese (from present day Anatolia) could include milk from asses and mares.

Today, we may well mainly associate goats’ cheese with France. Legend has it that the goats that now roam the regions of Poitou, Périgord and Aquitaine are descendants of those brought to Spain by invading Arabs in the eighth century. When the Arabs attempted to take France too, they were defeated in a battle near Poitiers in 732. However, the troops had brought along herds of goats to sustain themselves and some of these didn’t make the trip back home. This is allegedly the reason behind the popularity of goats’ cheeses in the region, and some say even accounts for the cheese names such as Chabichou, said to come from an Arabic word for goat. While this story may not be entirely true, French goats’ cheeses – especially chèvre – became popular around this time. We also know that goats’ cheese-making

was popular across the border in Catalonia. The fourteenthcentury cookbook Sent Sovi, the oldest surviving culinary text in Catalan, preserves a recipe for Mató, a cheese a little similar to ricotta, eaten as a dessert. Another Catalonian cheese is the Garrotxa St Gil, a pasteurized cheese that came about in its current form in the late 1970s, when jipsosos (hippies) from Barcelona fled to the countryside to avoid persecution at the end of Francisco Franco’s dictatorship. There they began making cheese, and the Garrotxa was one that was made from pasteurized milk because the older generation in the region kept falling ill from brucellosis, a bacterial infection.

My favourite now has to be feta cheese, technically a combination of sheep and goats’ milk, which is formed into blocks and aged in brine. The method is documented in Cato the Elder’s De Agri Cultura from the second century bc and similar cheeses are described throughout the medieval period.

You can make a goats’ milk version of pretty much any cheese and, for the most part, they are better for you than cheeses from cows. They’re higher in protein, lower in sodium and cholesterol, and slightly lower in fat. Goats’ cheeses also contain more capric acid (‘goats’ acid’, named so because of its sweaty, unpleasant smell), which has many health benefits, and plenty of nutrients.

Strangely, however, the Norwegian version has yet to take on the world.

Caligula is known to history as a cruel madman, but at least he had a sense of humour. The deranged Roman emperor particularly loved watching the comedian Mnester, Suetonius writing that Caligula ‘used to kiss the pantomime actor Mnester even in the middle of the games. And if, when Mnester was performing, anyone made the slightest noise, he had him dragged from his seat and flogged him himself.’

Once, when someone in the audience made such a disturbance, an annoyed Caligula punished the culprit by playing a convoluted practical joke: he sent a centurion to him with a message that had to be taken immediately to King Ptolemy in Mauretania (roughly modern-day Algeria, with some of Morocco). The man sailed from Rome and handed the letter to the king. It simply said: ‘Do nothing at all, either good or bad, to the bearer.’

This combination of absurdity and revenge is also noticeable in the sixth-century tale of Anthemius of Tralles. Anthemius was an architect and mathematician employed to reconstruct Hagia Sophia, the church in what was then Constantinople, after a fi re.

He had a disagreement with Zeno, a neighbour, which resulted in a legal victory for the latter. Anthemius sought revenge, and put several cauldrons of water in a cellar that ran under Zeno’s house. These were heated, while the cauldrons

were tightly covered with animal skins, so the pressure grew and grew. Anthemius employed leather pipes to pump the steam from the cauldrons into the base of one of Zeno’s fi ner rooms on the ground floor. So strong was the force of the steam that it made Zeno’s floorboards shake violently. Zeno and his friends fled from what they believed to be an earthquake, and Zeno soon became a laughing stock when talking so earnestly about ‘the earthquake’, when almost nobody else had experienced it.

Jonathan Swift, the Anglo-Irish satirist most famous for writing Gulliver’s Travels, had an aversion to the almanacks that people bought to try to predict the future. Swift particularly took against John Partridge, a prolific almanack printer.

In 1708 Swift ran his own predictions against Partridge’s, while writing under the pseudonym of ‘Isaac Bickerstaff ’, a supposed rival in the almanack world. ‘Bickerstaff ’ apologized for his fi rst prediction – that Partridge would be killed by ‘a raging fever’ on 29 March. Straight after that date, ‘Bickerstaff ’ published The Accomplishment of the first of Mr Bickerstaff ’s Predictions, which claimed to be a relating of Partridge’s pitiful deathbed scene – accompanied by an alleged confession by the dying man in which he admitted that he was a fraudster. While Partridge eventually convinced people that he was still alive, he could not shake off the ridicule that Swift had lain at his feet. Credibility shot to ribbons, Partridge produced no more almanacks.

A long-lived practical joke in London involved ‘the washing of the lions’ at the Tower of London on April Fool’s Day. First recorded in 1698, the joke was still in practice deep into the nineteenth century – a ticket to the 1856 performance can be found in the Tower’s archives.

In 1848 tickets were printed that promised to allow the ‘bearer and friends’ admittance to the White Tower, on 1 April, to witness the lions receiving their annual bath. When some duped guests were refused entry, such a rumpus ensued that the warders had to whistle up some reinforcements. Perhaps it is more of a hoax than a practical joke, but another April Fool’s spectacular took place in 1957, when the BBC ran a three-minute report on a supposed bumper harvest on spaghetti trees in Switzerland. The combination of fi ne weather and an end to the dreaded ‘spaghetti weevil’ were given as the reasons for the bonanza, and the report – viewed by 8 million people – was given added credibility because it was voiced by the venerated commentator Richard Dimbleby.

The 1950s was a time when most British people only encountered spaghetti in chopped up strips, doused in a red, tangy sauce and emptied out of a tin. When viewers rang in the next day to ask how they might also grow spaghetti, the BBC suggested they ‘place a sprig of spaghetti in a tin of tomato sauce – and hope for the best’. CS

Near Monreith Bay in Galloway, just off the road to Point of Lag from the A747, you will fi nd a sculpture in bronze of an otter sitting on a rock looking out to sea. It commemorates the strange and captivating Gavin Maxwell, of the family and clan that has lived in those parts for centuries. He was a wonderful nature writer, gay and bipolar, served in the Special Operations Executive in the war, went to live with the marsh Arabs of Iraq in the 1950s and brought home a pet otter, Midge, whom he wrote about in Ring of Bright Water. It sold a million copies and was made into a feature fi lm with Virginia McKenna and Bill Travers that traumatized a generation of animal lovers.

Not far from the bronze otter, opposite the car park to St Medan’s Golf Club, is the ruins of Kirkmaiden church, one of the oldest in Scotland. Many Maxwells repose there, some in the unusual neo-Norman burial chapel carved crisply from local sandstone, unfortunately in some disrepair now.

The last to be immured in it was Sir Herbert Maxwell in 1937, a naturalist, Tory MP and famous salmon angler, who chaired the Royal Commission on Tuberculosis in 1897 and was the grandfather of Gavin. The kirkyard’s most spectacular resident, however, is not a Maxwell, but François Thurot, the Dijonnais pirate.

How did a French pirate come to be interred among Scottish lairds on a distant shore?

The grandson of a Captain O’Farrell, who served in the Irish Brigade of the French army, and from whom he perhaps inherited spirit and temper, Thurot was brought up in NuitsSaint-Georges, twinned with Hitchin, in the Côte-d’Or.

Winemaking, for which the region is famous, was not for him, and he was apprenticed to a surgeon at Dijon, but when his father died and his mother required fi nancial assistance, he chanced across some silver at an aunt’s house and pawned it. An ungenerous accusation of theft followed and he ran away to sea just in time for the War of the Austrian Succession, enlisting as a ship’s surgeon on a privateer that sailed from Le Havre. It was immediately captured by the British and Thurot was imprisoned on a prison hulk at Dover, where he learned to speak English. He escaped, stole a small boat and returned to France, where he must have impressed his superiors, for he was given command of a ship aged only twenty.

They chose well, for he captured several British merchant ships before the war ended, which enabled him to develop a sideline in smuggling, until in 1753 Customs Men seized his ship, the Argonaute, off the coast of Ireland.

This only intensified his anti-British feeling, and when the Seven Years War broke out he was given command of a corvette and laid into the British with notable flair. He sank or captured around sixty ships before being promoted to captain of a forty-four-gun frigate, the Belle-Isle.

Over the next three years he created havoc among British shipping and became celebrated and feared in equal measure as a kind of cross between Drake and Blackbeard. In 1759 the French government gave him command of a squadron and 2,000 soldiers for an expedition to Ireland, where he was particularly admired, partly because of his ancestry and partly owing to the ambivalence of its people to British interests.

Thurot was always unlucky with weather, and storms wrecked half the squadron and blew the surviving ships off course. The soldiers’ commanding officer urged him to abandon the mission, but Thurot refused, pausing only to put in at Islay, where the starving crew dug potatoes out of the soil with bayonets.

He anchored off Carrickfergus on 21 February, and overpowered its garrison with what was left of his men, who unfortunately started pillaging the town even though he had given his word they would not. This alienated local feeling and he was obliged to re-embark his troops and set sail on 26 February. On the 28th, off the coast of the Isle of Man, Thurot’s Belle-Isle met Captain John Elliott’s Æolus, which fi red a devastating broadside.

When Elliott’s crew boarded the Belle-Isle it was discovered Thurot had been killed, and his body thrown overboard, along with 159 of his men who were lost to Elliott’s four. Among the survivors was a Miss Smith of Paddington, Thurot’s mistress, or so it was said. This was especially awkward, for at home his wife had just given birth to a daughter, Cécile-Henriette.

His short life – he was thirty-two when he died – was so vivid he was very quickly mythologized. All England lamented the death of a sailor who fought for ‘honour rather than plunder’, all Ireland chorused ‘blessed be the day that O’Farrell came here’.

Meanwhile his body, identified ‘by a few tokens’, washed up in Luce Bay off the Galloway coast and was recovered by the laird of those parts, Sir William Maxwell, who paid for his funeral and attended as chief mourner.

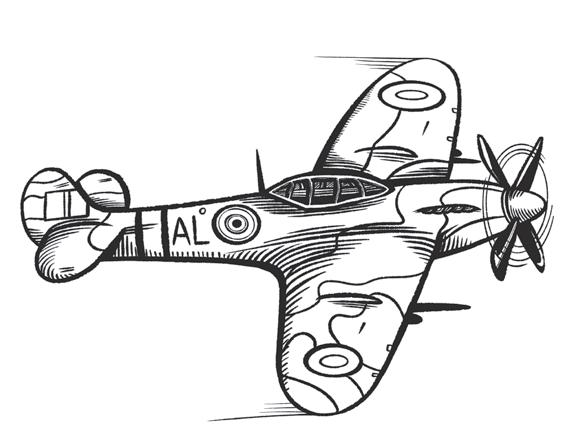

I live on the South Downs, about half a mile from the white cliffs of the Seven Sisters. Every once in a while a Spitfi re fl ies overhead and we all look up, point and go ooh. Spitfi res are rare today, but not in the Second World War, when the Battle of Britain was fought in these skies. For Britons, could there be a more iconic aircraft than this, defending us from the Nazi Luftwaffe?

Probably not, but there is another aircraft which played an even nobler part in that fight and which gets insufficient credit in my view. It is the Hawker Hurricane. That’s Hurricane to rhyme with honeybun rather than windowpane.

A single-seat fighter, like the Spitfi re, it can be recognized by the Hurricane’s rather plain appearance, with straightedged wings, unlike the Spitfi re’s ellipse, a hump-backed appearance thanks to a cockpit mounted high for better visibility and, if you look closely, rather corrugated flanks.

It was designed in the 1930s by Sir Sidney Camm of Hawker in consultation with the RAF, which was looking for monoplane fighters to replace his Hawker Fury biplane. It

would be hard to overstate the technological advance of the Hurricane over its forebear, with a single wing, retractable undercarriage, and the same Rolls-Royce Merlin engine that also powered the Spitfi re (they sound very similar). It also had eight machine guns capable of fi ring 1,000 rounds per minute. This last capability was introduced thanks to calculations by Hazel Hills, the thirteen-year-old dyslexic daughter of the Air Ministry’s Science Officer, who proved to be not only an excellent mathematician but also, in later life, an eminent children’s psychiatrist and a world-renowned expert in autism.

In some ways, however, the Hurricane looked backwards rather than forwards. The fuselage was a steel tubular design with a wood frame covered with painted Irish linen stretched over it by dressmakers, hence the corrugation. The tail also looked antique, as if it had been transplanted from one of Camm’s biplanes rather than created for a new era of aeroplane design.

Construction of the Hurricane began in 1936. It was the fi rst mass-produced RAF plane to break the 300 mph barrier, could fly at an altitude of 16,000 feet and climb to 15,000 in about five and a half minutes. Its chief test pilot reported that ‘the aircraft is simple and easy to fly and has no apparent vices’. By the time war with Germany was declared in September 1939, 500 RAF Hurricanes were operational, with another 3,500 on order.

Hurricanes did far more damage to the Luftwaffe than Spitfi res during the Battle of Britain. There were more of them – thirty-two squadrons compared with nineteen – but they were slower and less manoeuvrable, workhorses rather than show ponies, used to attack bombers rather than their fi ghter escorts, which were left to the Spitfi res. In some