PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London sw11 7bw penguin.co.uk

First published 2026 001

Copyright © Maggie Campbell, 2026

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception

Set in 12.5/14.75pt Garamond MT Std

Typeset by Six Red Marbles UK , Thetford, Norfolk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d02 yh68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

isbn: 978–1–405–96640–5

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper

For the real Dr Haslam. Holcombe’s loss is Hale’s gain.

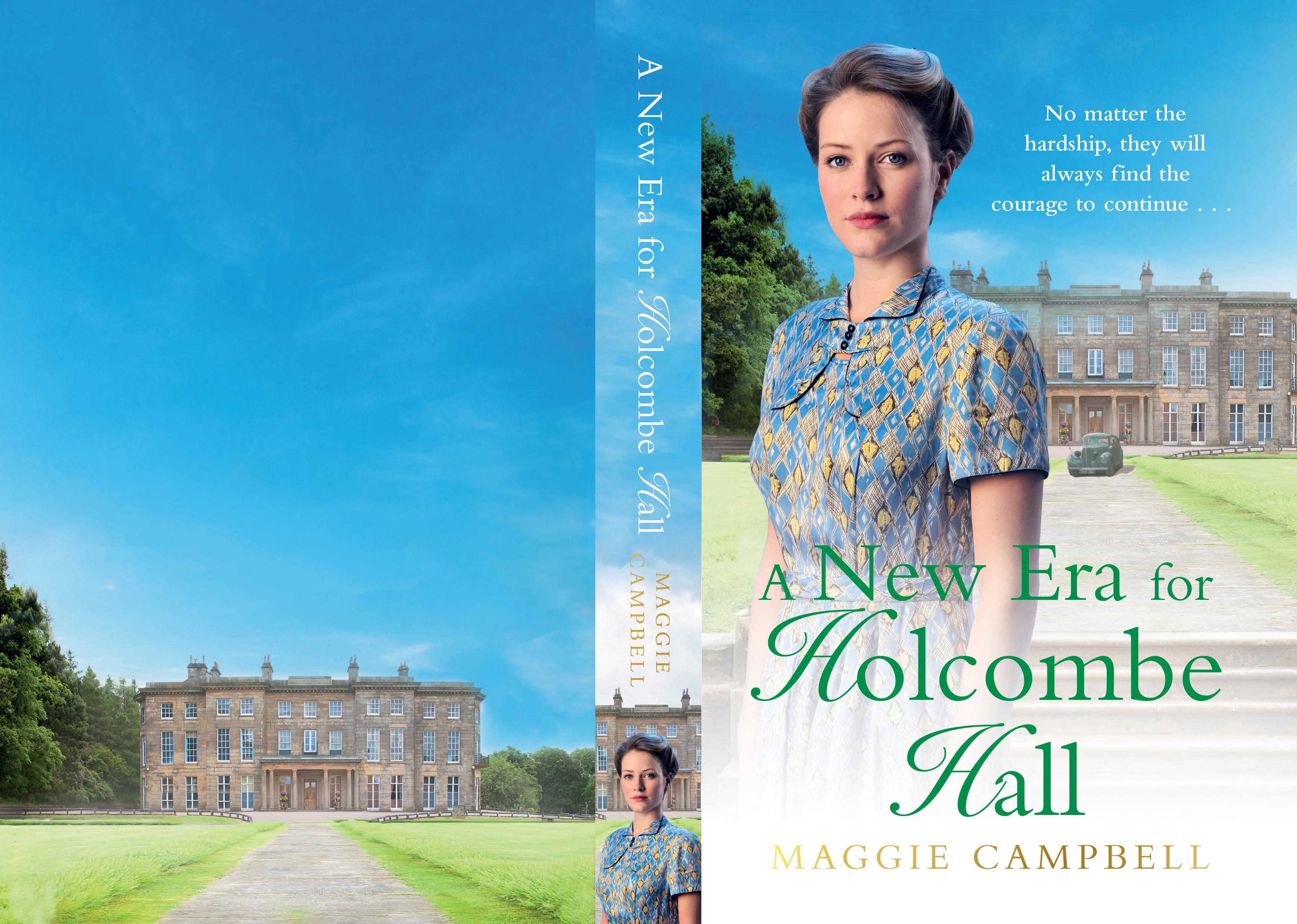

A New Era for Holcombe Hall

The muscles in Florrie’s forearms complained as she pushed the heavy old pram along the gravelled path that skirted the grand frontage of Holcombe Hall. She’d been walking only twenty minutes, and the starched blouse of her housekeeper’s uniform was already clinging to her skin from the effort. Yet Florrie relished being away from the stifling warren of rooms and corridors below stairs, feeling the sun on her skin.

‘Look at all this, eh?’ she said to the chubby baby sitting in the pram. She stopped to take in the deep flower beds to her left, where bright blue delphiniums swayed in the warm breeze, and clambering pink roses and honeysuckle snaked their way up and around the tall drawing room windows. To her right, the groomed turf of the lawns was already starting to yellow ever so slightly in the June heat, but the glossy leaves of the magnolia sapling that the staff had planted in memory of her predecessor were still a lush green. ‘One day, Sir William, all this will be yours. Imagine that! The house. The gardens. The farmland beyond. Even Bertha’s tree. And I tell you what, chuck, it doesn’t get much better than Holcombe Hall on a sunny Sunday morning.’

The baby squinted up at her, nonplussed. He sneezed in the strong sunlight.

‘Bless you!’

Florrie paused momentarily to wipe the baby’s nose on a lace-trimmed handkerchief, then she continued on her way. When the old Victorian wheels sank into a particularly deep patch of gravel, the pram ground to a halt.

‘Oh, fiddlesticks! I wish your mother had forked out for a better pram than this old bucket from the year dot,’ Florrie said. ‘I’ll have to get Thom to see if he can do something about the paths . . . or the wheels, or both.’

The baby sneezed a second time, this time losing his balance and falling backwards on to the soft pillow at his back. He let out a cry of complaint.

Florrie leaned over and sat the baby up. ‘There, there, Sir William! Oh, what a fuss!’

A bumblebee flew over and started to lazily buzz around the baby’s face, just as Florrie was trying to adjust the brim of his sunhat to shield his eyes. William let out a horrified shriek.

‘It’s only a bee, young man. Just a buzzy bumble. Keep still and it won’t harm you.’ Florrie waved the insect away, but the baby was still fretful. She regarded his screwed-up little face – the image of his grandfather, the old Lord Harding-Bourne. ‘Ooh, I do wish that nanny of yours would take you out in the fresh air more often.’ She straightened the Peter Pan collar of his little outfit and stroked his cheek. ‘You need a distraction, other children.’ She sighed. ‘I wish our Nelly, Alice and George could have come out with us for a walk today. It’s supposed to be my day off, after all, and they’re my nieces and nephew – flesh and blood. Me and my mam are all they’ve got left.’

A bitter memory of her sister’s untimely demise presented itself: gasping for her last breath on a Manchester

Royal Infirmary ward, leaving three children under the age of five behind. If only Irene hadn’t been living in slum conditions. If only she’d had the money to see a doctor before the pneumonia had really got a grip . . . Florrie batted the mental image away and looked down at her infant charge.

‘But here am I, babysitting you . . .’ She spoke in a singsong voice and softly tickled him under the chin so that he started to giggle. ‘Just so Miss Talbot can sit in chapel for half the day. And you’re not even allowed to mix with my lot, are you? No! “Hoi-polloi”, Lady Charlotte calls them.’ She tutted.

In the distance, Florrie could hear the thrum of a biplane’s engine. Shielding her eyes from the bright sunshine, she looked up into the azure skies.

‘There she is,’ Florrie said, pointing to the dot in the distance, growing ever larger as it flew towards them. ‘There’s your mother. Fancies herself as Amelia Earhart, does our Lady Charlotte.’ Florrie shook her head. ‘And your Aunty Daphne’s her willing sidekick. What a pair!’

Frowning momentarily, Florrie bit her tongue, though her only audience was a tiny babbling babe. She advanced towards the library windows and peered in, spotting Lady Elizabeth sitting in an armchair, reading in the strong sunlight that streamed in.

‘Oh, good. Your grandmother’s up and about,’ she said to the baby. ‘First time in a while and all. Very glad to see her out of her sickbed. It’s a right shame her gout took a turn for the worse, just as you arrived. She’s definitely not herself, these days . . . unsurprisingly, I suppose.’

A moving shape within the shadows of the library stacks caught Florrie’s eye – a tall, slender man, instantly

recognizable as Sir Richard. He emerged from the gloom and took his place by Lady Elizabeth’s side, placing his hand on his mother’s shoulder, a smile in his eyes as he spoke to her. Though he was dressed simply in light slacks and a short-sleeved polo shirt, buttoned down at the neck, he was ever the elegant nobleman Florrie had privately worshipped since she’d arrived at Holcombe Hall at the tender age of fifteen.

‘And there’s your father!’

When Sir Richard looked up and through the window, he locked eyes with Florrie.

Florrie smiled and waved tentatively, aware that her cheeks had flushed and her pulse had quickened. Even though she’d been courted by handsome, dependable Thom for the last eleven months, there was still a secret place in Florrie’s heart for her employer. Had Sir Richard not gone out of his way to give Mam and Irene’s destitute children the chance of a new life, enjoying comfort and security beneath the lovingly repaired roof of the old gamekeeper’s cottage? Had he not been true to his word, raising money to fill the new Harding-Bourne Trust’s coffers, so that laid-off mill workers, coal miners and ship builders might avoid penury?

‘He’s a grand feller, your father,’ she told the baby. ‘You’re a very, very lucky boy to have a daddy like that. I hope you’ll realize that when you grow up.’

Sir Richard waved back, pointed to them both, and said something to his mother. Lady Elizabeth looked up and peered through the window. She smiled weakly, raising a handkerchief at Florrie and the baby by way of greeting. Yet even with distance and a window between them,

Florrie could see uncertainty in the old lady’s eyes. Lady Elizabeth knew that affection for her middle son was not the only secret that Florrie guarded.

‘Families, eh?’ Florrie said. She held Sir William’s chubby little hand and waved it at his doting father and grandmother. Turning away from the window, she resumed their walk along the path. ‘Doesn’t matter how rich you are, families are always complicated.’

She was just reflecting that she and Sir Richard had both lost siblings too young when she became aware that the distant buzz of the biplane was no longer quite so distant. Florrie looked up to see the aircraft nearing Holcombe Hall.

‘Ooh. Looks like your mother is coming into land at last. She might actually pay you some attention before . . .’

Florrie’s words drifted away on the light summer breeze as she tried to make sense of the sight of the biplane approaching in entirely the wrong direction for the makeshift airstrip in a neighbouring field. ‘Hang on a minute . . .’ It was also flying altogether too low, and the engines were now making a sputtering noise. ‘What’s going on here? Oh, blimey!’

The biplane buffeted, skimming the treetops of Holcombe’s woods with its wheels. Lady Charlotte was clearly visible in the cockpit. Though her head was clad in her close-fitting leather helmet and she was wearing goggles, it was clear she was grinning. But why?

The propeller slowed and the engine cut out.

‘They’re going to crash!’ Florrie yelled. ‘Good Lord, no!’

Closer and closer the biplane glided, heading straight for the Hall, with Florrie and the baby directly in its path.

Florrie snatched Sir William out of his pram and clutched him to her chest, then ran away from the sandstone walls of Holcombe Hall and on to the lawn. Her foot caught in her long skirt and she stumbled.

At that moment, Sir Richard sprinted out of the library’s French doors towards them. The biplane was seconds from impact, with Lady Charlotte and Daphne waving absurdly at them, as if they hadn’t a care in the world; as if they weren’t about to coast to a fiery death.

Just as Sir Richard reached Florrie and the baby, pulling them to the ground and sheltering them with his body, Florrie heard the engine of the aircraft cut back in. She craned her neck to see the propeller start to spin again, and then the biplane shot up, up, up and over the steep rooftops of the stately home.

The sound of Lady Charlotte and Daphne’s hoots of laughter trilled on the air.

‘What in God’s name . . . ?’ Sir Richard sat up, freeing Florrie and the baby from the protective cage of his arms and torso. He looked up, scowling at the aircraft. ‘Wanton recklessness! I shall have to have stern words with my wife when she returns.’

Florrie gently shushed the fretting baby. ‘There, there, Sir William. What a to-do! What a to-do! All over now, eh? All safe and sound.’ She eyed the biplane as it banked steeply, this time heading for the landing strip that had been mown into the neighbouring field. Much as she would love to tell Sir Richard exactly what she also thought of Lady Charlotte and Daphne, she kept her opinions to herself. ‘And the main thing is, nobody was hurt.’

‘But we could have been,’ Sir Richard said, getting to

his feet. He helped Florrie up and then held his hands out to take his son. ‘Here. Give him to me.’ Supporting the little boy on his hip, he kissed his cheek and wiped the tears from his eyes. ‘There, there, William. Papa’s here.’ Sir Richard turned to Florrie wearing an inscrutable expression. ‘Thank goodness Charlotte pulled the nose of that blasted toy of hers up in time. I could have lost everything I hold dear to me in a split second of poor judgement.’

Florrie watched his Adam’s apple rise and fall in his throat. She glanced rapidly down at the bulky seat of the baby’s trousers before Sir Richard could catch her eye. ‘Well, there’s not a scratch on the house, and your son and heir’s fine, too,’ she said with a forced chuckle. She took the baby back from him and sniffed his bottom with a grimace. ‘Though I think this one could probably do with being changed. Let me take his little lordship back to the nursery. My mam’s had a load of his nappy squares drying on the line all yesterday.’ She cooed at the baby. ‘Kitten soft and white as the driven snow, they are. Yes!’

She turned to leave Sir Richard – scratching his head and peering at the distant hedgerow, beyond which his wife’s biplane was just landing.

Florrie retrieved the pram, settling the baby back inside. She wondered how much of the fiasco Dame Elizabeth had witnessed through the library windows. As she pushed the cumbersome pram towards the grand stone staircase of the main entrance, Sir Richard’s younger brother, Sir Hugh, came skipping down the steps, taking them two at a

time. He was wearing tennis whites, and his button-down collar was unfastened, his brilliantined hair dishevelled, as usual. He carried a tennis racket over his shoulder.

‘What ho, Florrie! Was that my daredevil sister-in-law I just saw, almost crashing into the house, with my reckless wife in the passenger seat?’ He laughed, as though Lady Charlotte’s stunt had been a terrific wheeze.

Florrie had no time for Sir Hugh’s nonsense. ‘Sir Hugh, would you mind terribly helping me up the stairs with the pram, please?’

Behind her, she heard laughter in the distance, coming from the direction of the makeshift airstrip. She turned around to see Lady Charlotte, walking side by side with Sir Hugh’s wife, Daphne. Both women were swinging their flying hats and goggles, elbowing each other and erupting into fits of giggles.

Sir Hugh ignored Florrie’s plea entirely. He jogged towards the women, leaving Florrie to carry the baby and heave the pram up the stairs on her own. Grumbling beneath her breath, Florrie paused in her ascent when she saw Sir Richard, marching across the lawn from the direction of the library to meet his wife and sister-in-law. The summer breeze carried his voice towards Florrie.

‘Charlotte Harding-Bourne, I wish to have a word with you! In fact, I wish to have several.’

Lady Charlotte merely pushed her hat into her husband’s chest. ‘Oh, don’t be such an interminable bore, Dickie. Didn’t you see our terrific, death-defying stunt?’ She flashed a mischievous grin at Daphne.

‘Such fun!’ Daphne said. ‘I swear, Dickie, she’s every bit as good as Earhart!’

‘But, need I remind you, Charlotte, you’re not Amelia Earhart. You are not even a skilled pilot.’

‘I beg to differ!’ Lady Charlotte blinked defiantly at him. ‘A mere hobbyist could never have pulled off a manoeuvre like that.’

‘You are a wife and mother, Charlotte. A member of the nobility, who should be behaving in a seemly manner, befitting her social standing.’

‘Oh, do stop being such a stick-in-the-mud. You know I love flying,’ Lady Charlotte said. ‘Hans was an absolute darling for teaching me. I think my aerobatic skills this morning were sublime.’

‘Sublime? Surely you jest? You could have crashed and died, taking half the house with you!’ Sir Richard’s face flushed an uncharacteristic shade of red. He balled his fists so tightly that even from a distance, Florrie could see his knuckles stood proud like white marbles. ‘More to the point, you could have killed our son !’

‘Nonsense. I can see William over there on the steps with Florrie.’ Lady Charlotte waved to Florrie absently. ‘He’s in perfectly capable hands, and is one not allowed a break from the travails of motherhood on a delightful Sunday morning?’

Florrie was so engrossed in eavesdropping on the conversation that she jolted with surprise when the pram seemed to move of its own accord.

‘May I?’ A familiar man’s voice, at her side.

She turned to find Arkwright, the butler, yanking the pram from her. ‘Come inside, Florence,’ he said. ‘It will do no good to bear witness to the antics of our employers.’

‘No. I suppose you’re right.’

‘Sir Richard sails to India tomorrow.’ With his back to the house, Arkwright started to pull the cumbersome pram up one step after another. ‘And the maids you’ve tasked with packing are at each other’s throats over which of his suits to put in the trunk.’ He glowered at her pointedly. ‘Best you concern yourself with the ructions below stairs, rather than the tomfoolery of our betters above, eh?’

‘I see you’ve picked out heavy gabardine slacks for India, Clary,’ Florrie said to the new junior maid who had been tasked with packing for Sir Richard. ‘Do you think that’s wise? I mean, he’s going to Bombay, not Penrith! It’s going to be boiling hot one minute and tipping with monsoon rain the next.’

Clutching the offending trousers, Clary stared at Florrie, wide-eyed and unmoving. It was as if fear had frozen her to the spot. Then her lower lip started to tremble.

‘Don’t cry! I wasn’t rebuking you. I was asking you a question. In a job like this, you have to show some initiative.’

Rummaging in Sir Richard’s wardrobe, Florrie’s friend and one-time contemporary, Sally, glanced back at her, wearing an exasperated expression. ‘I told her, and she wouldn’t listen. If I say black, she says white. Take no notice of this “little girl lost” routine. This one’s got plenty to say for herself when you’re not in earshot.’

Adjusting a fidgeting Sir William on her hip, Florrie looked enquiringly at Clary.

‘That’s not true!’ Clary said, shaking her head vehemently. ‘I’m trying my best.’

Before her, Florrie saw a girl of fifteen, whose secondhand maid’s uniform was sack-like on her diminutive frame. She wondered if she had appeared equally vulnerable when she’d arrived at Holcombe Hall twelve years

earlier as a fifteen-year-old domestic trainee – little more than a child.

‘Put the trousers back, Clary,’ she said gently. ‘And listen to Sally, please, because she’s more experienced than you. I know you think you’re being told off, but Sal’s only got your best interests at heart. If you pick up sloppy habits now, you’ll struggle down the line. Running this house like clockwork depends on us all knowing our place, trusting those above us, and doing our jobs to the very best of our abilities.’ She watched Clary fumble with the trousers and hanger. ‘Neatly, mind!’ She turned to Sally. ‘Sir Richard needs white tie, black tie; he’s got an ivory dinner jacket somewhere.’

‘Got it!’ Sally pulled the jacket out of the wardrobe with a flourish.

‘Aye, he’ll want that.’ Florrie nodded. She addressed both of them. ‘His smoking jacket, too. Linen suits only for formal daytime, please, girls. Short-sleeved shirts and polo shirts; as many pairs of Bermuda shorts as he’s got for sightseeing and suchlike. Cricket whites, tennis whites, golf attire.’

‘He’s doing all that in the heat?’ Sally took out a dust bag and hung it on a door of the triple wardrobe. ‘What’s that new Noël Coward song? “Mad Dogs and Englishmen”?’ She lifted the cotton bag to reveal a burgundy velvet smoking jacket, which sported a black satin quilted collar and a fringed belt.

Florrie strode over to the jacket. Between the finger and thumb of her free hand she tweezed a stray piece of white cotton from the collar and smoothed down the velvet. ‘Ours is not to question why, Sal. If Sir Richard

wants to go “out in the midday sun”, I’m sure there’s some thinking behind it. It’s a business trip, isn’t it?’ She turned the jacket over to check for moth holes but was satisfied there were none. Before little Sir William could grab the fringes on the belt, she moved back towards the dressing table. ‘The new Viceroy Lord Willingdon’s a bit long in the tooth for cricket and tennis, I shouldn’t wonder, but Sir Richard’s after securing HB Steel’s stake in the Raj’s rail network. Apparently a lot of deals get done on the golf course and the cricket pitch.’

She turned back to Clary, who was still fumbling with the hanger and the gabardine trousers.

‘I can’t do it, Miss Bickerstaff,’ the girl said. ‘I can’t get them to stay on. They’re right fiddly.’

Sir William grabbed at the tight bun in Florrie’s hair and tugged hard, squealing with delight.

‘Well, Sally will have to teach you, because I’ve been left holding the baby, quite literally.’ She prised her bun free and looked at her charge with affection.

‘I’ve already showed her twice,’ Sally said.

‘No, you didn’t,’ Clary insisted.

‘I most certainly did, so you couldn’t have been paying attention.’ Sally turned to Florrie, a look of exasperation on her face. ‘I did show her.’

Florrie sighed. ‘Clary, you must pay attention to Sally and do as she says.’

‘Yes, Miss Bickerstaff. But what if I disagree with her?’

‘Sally has packed more trunks for Sir Richard than you’ve had hot dinners. Do what you’re told and do it well, please. Is that clear?’

Clary bobbed a curtsey, little blotches of red appearing

on her wan cheeks. ‘Yes, Miss Bickerstaff. Sorry, Miss Bickerstaff.’ The trousers slid on to the floor.

‘Get on with your work, ladies. Sir Richard departs at six o’clock tomorrow morning, and his trunks and cases must all be locked, labelled and ready for Thom to load into the luggage car at half past five, sharp.’

‘There. That’s much more comfortable, isn’t it, Sir William?’ Florrie said to the baby, once she’d cleaned him up and wrapped a fresh nappy around him.

Happily lying on a quilted pad on top of a Louis XIV dresser that had been repurposed to suit his nappy changing needs, the baby gurgled at her and kicked out his chubby legs. He looked up at the playful cherubs Lady Charlotte had insisted be painted on to the walls of the spacious nursery and blew a raspberry.

‘Now, let’s get this nappy fastened, and maybe I can hand you over to your mother, seeing as your nanny’s absconded to spend a leisurely morning with Holcombe’s Methodists.’ Florrie struggled to get the stiff, oversized safety pin open and pricked the pad of her thumb. ‘Ow!’ She wiped a bead of blood on to the corner of the muslin she’d used to wash her temporary charge’s bottom. ‘Darn it! Where on earth is that nanny of yours? She should have been back for midday, but Miss Talbot thinks her religious fervour means the rules don’t apply to her, doesn’t she? Yes!’ She tutted. ‘My own day off, and here I am, wiping your noble little bottom when I’m supposed to be taking our Nelly, Alice and George for a walk up Holcombe Hill.’

Once she’d put Sir William’s trousers back on, Florrie picked him up and descended the servants’ staircase,

emerging by the drawing room. From the hallway, she could hear the chatter and laughter of Sir Hugh, Daphne and Lady Charlotte, accompanied by the crackling, tinny sound of jazz music coming from the gramophone.

‘Here we go . . .’ Florrie kissed the silken wisps on Sir William’s head and knocked on the door to the drawing room. She pushed the door open to find the two women still in their flying garb – jodhpurs, knee-length leather boots, fine-knit jumpers with scarves tied jauntily at their necks – foxtrotting to the music. Sir Hugh was pouring gin into tall crystal glasses which had clearly already held at least one drink already. There was no sign of Arkwright or any of his valets.

‘Ah, Florrie!’ Sir Hugh said. He held the bottle of gin towards her. ‘Do pour us each another Tom Collins, there’s a good girl.’

A good girl? Florrie thought, her face already starting to ache from the accommodating smile she was willing herself to maintain. I’m the housekeeper. I thank God every day for the opportunity that prematurely came my way because of poor Bertha dying, but I am the most senior female member of staff now. Yet to this lot, I will never be anything more than ‘good girl’. And I’m still holding the baby. ‘Of course.’ She turned to Lady Charlotte. ‘Ma’am, would you like to take your darling son so I can pour the drinks?’

Lady Charlotte’s smile was fleeting. ‘Hand him here.’ She took Sir William from Florrie, holding him at arm’s length, as if she were his distant relative with no real experience of children. Then she lowered herself into an armchair, stiffly perching the baby on her knee. ‘There, there, William. Mama’s here.’

Little Sir William started to struggle against her grip. Grunting and wriggling in complaint, he accidentally hit his mother in the face.

Lady Charlotte looked down at him, aghast. ‘William! You perfectly horrid little boy. I’m your mother!’ Getting to her feet, she thrust the baby back at Florrie.

‘He’s teething,’ Florrie said, swapping the gin bottle for the distraught baby. ‘It makes babies short-tempered, is all. And I really don’t think he meant to hit—’

‘Where is Miss Talbot?’ Lady Charlotte snapped.

‘She’s at chapel,’ Florrie said. She patted Sir William’s back gently as he started to sob. ‘She’ll be back any minute now, I’m sure. In fact, she should have been back an hour and a half ago.’

‘Very well. I suppose I’ll fix these drinks, then, shall I?’ Lady Charlotte turned away from Florrie and started to pour gin into the glasses. She glanced back at Florrie and her son, wearing a look of exasperation . . . or was it disgust? ‘Thank you, Florrie. That will be all.’

Florrie curtseyed. Much as she ideally needed to leave Sir William with his mother – to bond if for no other reason – she knew a room full of stinking cigarette smoke and gin fumes was not the place to entertain a baby. Furthermore, she wouldn’t have felt comfortable leaving Lady Charlotte in charge of him.

‘Come on, flowerpot,’ she told the drooling, fractious boy. ‘Let’s take you down to the kitchens and see if Cook’s got something tasty for you to teethe on.’ She peered into his mouth and spied florid gums. ‘Bit of ice-cream might numb that pain.’

As soon as Florrie arrived at the foot of the stairs leading down to the kitchen, it was as if she’d entered the steam room of one of the Turkish baths Sir Hugh regularly eulogized about.

‘Hey up! Here she is,’ Cook said, rolling out pastry with gusto, her sleeves folded up to reveal the giant forearms of a woman who spent her life either kneading dough or else beating sugar and butter together with a spoon. ‘The Pied Piper of Holcombe Hall.’

Florrie groaned. ‘I don’t think carrying one babe-inarms makes me a Pied Piper. I haven’t seen our George, Nelly and Alice for days, because Miss Talbot insists Sir William be kept well away from them.’

Cook set down her rolling pin and approached Florrie and Sir William with floury hands held out. She rubbed Sir William’s florid cheeks. ‘Has our little lordship come to visit Cookie? Yes, he has! Does Sir William want a biccy to chomp on?’

‘Oh, I don’t think a biscuit would do him much good,’ Florrie said, swinging her charge out of Cook’s floury reach. ‘And you told me you don’t even like babies!’

‘Rubbish! Come here!’ Cook beckoned to Florrie as she marched across the kitchen, past the huge staff dining table. ‘Babies love chomping on something hard when they’re teething. It helps the tooth come through. Even I know that. And I’ve got some rock-hard macaroons that overcooked because a certain housekeeper has got my apprentice packing for Sir Richard’s trip to India.’

Florrie followed in her wake, savouring the buttery, almondy smell of baking that she trailed behind her. ‘It’s an economizing exercise, Cook. Sir Richard’s orders. We

must save money where we can, so all the girls have to double up on their duties now. Sally’s no different. She might be your apprentice, but she still has to pitch in above stairs when we’re stretched. I can’t give you preferential treatment.’

Cook looked back at her, rolling her eyes and waving her hand dismissively. ‘Don’t act like you’re doing me no favours, Florrie Bickerstaff. I’m not daft. Sally’s only training under me because she were terrible at everything else!’ She came to a halt by her oversized sideboard, on top of which she’d left her baked wares to cool on racks. ‘Anyhow, never mind all that.’ She picked up a deep brown, thick biscuit and held it out to Sir William. ‘I was saving these burnt offerings for the staff to dunk in their tea later . . .’

Sir William took the biscuit and chomped down on it. He grimaced and threw it on to the terracotta tiles of the floor.

Cook guffawed with laughter. ‘Charming! Be like that, then!’ She grunted as she crouched to pick up the broken pieces of macaroon.

‘I say, is my son causing a stir?’ A man’s voice emanated from the far side of the kitchen.

Florrie looked around to find Sir Richard standing at the foot of the stairs. She immediately bobbed a curtsey and smiled. ‘No, sir. I just thought I’d bring Sir William down to see if Cook had any ice-cream for his sore gums.’

‘Something cold? Why didn’t you say in the first place? I’ve just the thing.’ Cook reached into the Frigidaire that Sir Richard had recently had shipped over from America, and brought out a tub of something icy-looking. ‘Sorbet for tonight’s dinner do him?’

Sir Richard took his wriggling, fractious son from Florrie and accepted a spoonful of sorbet from Cook. The baby chomped down on the spoon and started to make grateful noises. ‘Ah, I do believe Cook has discovered the cure for all ills on a sultry June afternoon!’ His brow furrowed and he locked eyes with Florrie. ‘But why are you playing nursemaid to my son, Florrie? You told me you’d planned to spend your free day with your family. Where’s Miss Talbot?’

In Florrie’s peripheral vision, she could see the kitchen maid emerge from the labyrinth of corridors that extended below stairs. As soon as the girl spied Sir Richard, she retreated, carrying her mop and pail of sloshing water back towards Arkwright’s office. ‘Miss Talbot should have been back from chapel a while ago. But she’s not.’ She shrugged.

Sir Richard frowned. ‘And my wife?’

‘Lady Charlotte was . . .’ Florrie chose her words carefully. ‘. . . fatigued after her flight.’

Her employer tutted. ‘This really won’t do. Miss Talbot should return promptly to her nannying duties as soon as her chapel’s Sunday service has concluded. If her timekeeping is poor while I’m here, what on earth is going to happen while I’m in India? I can hardly postpone my trip to keep tabs on the nanny. It’s ludicrous.’

‘No, Sir Richard. Absolutely not.’

Sir Richard studied his son’s face intently, as if he was mulling something over. ‘Europe’s economy is in tatters since German and Austrian banking collapsed. I have to go to Delhi. If Harding-Bourne Steel goes under because I failed to drum up Indian locomotive orders, this young

man will have nothing to inherit at all, and the future of Holcombe Hall will suddenly be in question.’ He turned to Florrie. ‘We’re all cogs in a complex machine that keeps this estate running.’

Florrie nodded. ‘I know, sir. I know.’

‘The businesses, the staff, my family and I . . . Miss Talbot. If one part fails, the whole house of cards collapses, forgive my mixed metaphors.’ He smiled fleetingly. ‘I know my wife’s technically responsible for the nanny, but can you see to it that Miss Talbot improves her timekeeping? This tardiness can’t continue.’

Florrie knew better than to challenge Sir Richard on his assumption that she could make the slightest bit of difference to Miss Talbot’s behaviour. Nevertheless, she knew that fretting over his son’s nanny was the last thing her employer needed, just as he was about to set sail for a six-week-long odyssey. ‘Of course not.’

Cook caught her eye and nodded almost imperceptibly towards the window, set high into the wall. The kitchen was partially subterranean, so not only was the window the sole source of natural light and fresh air, but it also gave a limited view of the utilitarian courtyard next to the servants’ and tradesman’s entrance. Through the window, Florrie spotted a familiar pair of spindly legs, clad in thick black Lisle stockings, with feet wedged into highly polished but extremely old-fashioned, low-heeled shoes. Miss Talbot had returned, and Florrie determined to challenge her.

‘Leave it with me,’ she told Sir Richard, taking Sir William back from him. ‘I’ll have a word.’

‘Get out of the way, girl! You’re obstructing the corridor.’

The sound of Miss Talbot’s sharp voice made Florrie turn around. From the direction of Arkwright’s office, the shy young kitchen maid had suddenly reappeared, carrying her mop and bucket. Behind her was Miss Talbot, who unceremoniously pushed the girl aside.

‘Ah, at last,’ Florrie said.

The kitchen maid pointed at herself. ‘What? Me?’

‘No, Ginny, love. Not you. Sir Richard’s gone back upstairs now, so you can get on with your duties, please.’

Florrie fixed her gaze on Miss Talbot and then pointedly looked up at the large clock on the kitchen wall. ‘You took your time.’

Miss Talbot removed the black felt hat she’d been wearing and smoothed her grey hair, which had been tied tightly in a bun at the nape of her thin neck. ‘Is that any way to speak to a senior member of the household, Miss Bickerstaff?’

Florrie readjusted Sir William on her hip, her arm and leg muscles now aching after having carried or pushed him around for much of the day. ‘Need I remind you, Miss Talbot, that I am the housekeeper of this great home? Younger than you I might be, but junior to you I am not.’

‘I don’t answer to you, girl. I answer to the lady of the house. And I must go to church on a Sunday morning. As a practising Christian, that is my right.’ She clutched her

hard-framed handbag in front of her. ‘Now, when I’ve had a cup of tea, which Cook here is going to make me, I will then take over responsibility of Sir William.’

Cook wedged her fists on to her hips. ‘Hey! I’m not your lady’s maid. Don’t get me involved in all this. I’ve got three big game pies to make for dinner – for that lot above stairs and for us lot down here. You’ll be the first to grumble if your stomach’s rumbling at tea time and there’s nowt to eat.’ She pointed to the large pine Welsh dresser, where an array of crockery was neatly displayed on its shelves. Wedged in among the stacked plates was an urn. ‘You want a brew? There’s boiled water in the urn. Make it yourself!’

Florrie took the sorbet spoon from Sir William’s mouth and set it down on the dining table, taking a deep breath before she said something she regretted. It wouldn’t do to have Miss Talbot running with tales about her to Lady Charlotte or Dame Elizabeth. ‘Very well. Make yourself a cup of tea. But remember this, Miss Talbot: it’s my day off, and you’re reliant on my goodwill to attend chapel, because if you’re not looking after Sir William, someone else has to – either me or one of my girls. I’ve missed much of my day off thanks to you being back two hours late.’

Cook pointed to Miss Talbot with her rolling pin. ‘Taking advantage of Miss Bickerstaff’s good nature, you are. That’s not on.’

Miss Talbot glared at her with a sour-looking downturned mouth. ‘I thought you didn’t want to get involved, Cook.’ She marched over to the urn, ignoring Sir William’s outstretched hands, and spooned some tea into a small earthenware pot. ‘I’d take your own advice, if I were

you, and keep your opinions to yourself. I know my job. My references are impeccable. I’m not frightened by your schoolyard bullying, and if you two continue, I’ll not hesitate to report you both to Lady Charlotte.’ She rammed her hat back on her head emphatically. In awkward silence, she poured water from the urn into the pot, decanted some milk into a small jug, assembled a cup and saucer for herself and started to carry the lot on a tray up the back steps. ‘Kindly deliver Sir William to me in twenty minutes, Miss Bickerstaff. I’ll be in the nursery.’

Florrie felt suddenly cold and light-headed. She looked at Cook.

‘Well,’ said Cook. ‘She’s a piece of work.’

‘What am I going to do?’ Florrie bit her lip. ‘I can’t have her taking liberties like that every Sunday.’ Cook shook her head and started to roll her pastry out again with noticeably more aggression than before. ‘She’s a troublemaker, that one.’ She looked up and fixed Florrie with narrowed eyes. ‘Watch your back, love. That’s all I’m saying. We’re all expendable, and don’t kid yourself otherwise.’

Florrie thought about how her mam and her nephew and nieces – George, Nelly and Alice – depended on her to supplement her mam’s insufficient income as the estate’s laundress. She nodded. ‘Aye. Point taken. Thanks.’

With Sir William delivered to his nursery and the care of a stony-faced Miss Talbot, Florrie finally found she could return to her stiflingly hot room to change out of her housekeeper’s plain black dress with its restrictive white collar into a comfortable outfit of her own. Since

becoming the housekeeper some eighteen months earlier, she had not only moved into a larger room (though it was still at the top of the house, under the eaves, along with all the other servants’ quarters) but she had also expanded her wardrobe for days off to include three new outfits – a striped, sleeveless summer dress that Mam had made for her, a green winter two-piece with a pleated skirt that Daphne had put out for the church jumble sale, and a pair of sky-blue wide trousers to be paired with an ivory fineknit, short-sleeved top. Mam had made the trousers by repurposing and dying a fine linen tablecloth that Dame Elizabeth had insisted had reached the end of its useful life. The top was a hand-me-down from Lady Charlotte, but the silken fabric felt luxurious and was still in perfect condition but for one small ladder.

Now, Florrie stood in her scratchy, utilitarian undergarments, staring into the wardrobe. She unpinned her hair, pulled out the wide-legged trousers and ivory top, put them on and headed outside into the afternoon sunshine. As she walked across the lawn towards the gamekeeper’s cottage, she sensed eyes on her. She looked back at the hall, but couldn’t spy anyone watching her from the windows, either on the ground floor or upstairs.

‘You’re being paranoid, Florrie Bickerstaff,’ she told herself, folding her arms over her chest. ‘Don’t let Lady Charlotte and Miss Talbot’s antics ruin the rest of your day off.’

‘Mam? Mam, it’s me!’ When Florrie knocked on the door of the gamekeeper’s cottage, nobody answered. She stepped on to the sun-baked earth of the deep border

that Thom had planted for her mother before moving-in day. Pushing aside the bushy hydrangea which hadn’t yet bloomed anew, since it had been cut back hard to reveal the old leaded windows, she peered through the glass. There was nobody in the parlour, and no sound coming from inside. Had her mother given up the ghost and gone out alone with the children?

Tracing her steps back to the front door, she looked up at the bedroom windows of the house. Always a handsome place, even when it had been abandoned to the elements, after undergoing the expensive refurbishment that Sir Richard had ordered, the cottage was now chocolate-box perfection. The afternoon sun highlighted the blush-pink lime mortar that sat between the lovingly restored upper storey timbers. The flint that the ground floor had been built in seemed to gleam today. The place was a welcoming sight. Yet nobody appeared to be at home.

Florrie heard a high-pitched shriek, carried on the breeze. She walked around the side of the house, pushing past a lilac-blooming potato vine to reach the back garden with its large vegetable patch, mature rhododendron bushes and clumps of perennial flowers spilling on to a lush lawn. Mam was pegging out brilliant white washing. In the middle of the lawn were the children.

‘It’s Auntie Florrie!’ George squealed, pointing. He was seated on the swings Thom had fashioned for the children with spare rope and timber.

Nelly and Alice were bouncing up and down on the homemade seesaw – also a gift from Thom. ‘Auntie Florrie! Yippee!’ they yelled in unison.

The children all dismounted and ran across to her.

Florrie felt Alice’s little arms wrap around her knees, while Nelly’s encircled her hips. George hugged her middle. ‘Hello, my darlings. Sorry I’m late.’

Mam picked up the empty laundry basket and walked over to them. She kissed Florrie on the cheek. ‘Hey up, love. I thought you were never coming. What took you so long?’

Florrie revelled in the familiar scent of her mother: clean washing and carbolic soap. ‘Miss Talbot.’

Mam raised an eyebrow. ‘Say no more. She reckons she’s a cut above us all, that one. Will you tell Sir Richard she’s taking liberties?’

Kneeling down to kiss the children, Florrie shook her head. ‘He’s seen it with his own eyes. He even commented on it earlier. But he’s off to India in the morning for six weeks, so he’s got more important things on his plate. He’s got no jurisdiction over the nanny, anyhow. That’s Lady Charlotte’s domain.’

Scoffing and tutting, Mam walked to the back door of the cottage. ‘The liberties we have to put up with, just because we need the wages coming in! Never changes.’ Mam looked up at the cloudless sky. ‘Still, at least the washing will dry, and her ladyship isn’t flying around like a drunken wasp.’

Given there was too little time left in the afternoon to allow for a walk, Florrie prepared a picnic and took the children into the walled rose garden, where the rose bushes were at the peak of their first flush and smelled like heaven.

‘When I grow up, can I go and live in the big house with you?’ Nelly asked, chewing thoughtfully on a ham sandwich.

‘Don’t speak with your mouth full, young lady,’ Florrie said. She turned her attention to Alice, who was taking her sandwich apart, layer by layer. She picked up the toddler’s mess and put it back on to her plate. ‘And don’t play with your food, Alice!’

‘But can I?’ Nelly cocked her head to the side.

Florrie gazed through the archway that led to the formal flower gardens beyond. She could see her darling Thom and his apprentice, hoeing the beds. Would Thom propose to her soon, she wondered? Her gut tightened as she considered the terrible choice she’d be forced to make if he did. There was no having her cake and eating it. She could get married and start her own family, but she would have to give up not just her job and income, but also her home for the last decade. Or she could continue to work, live in one of the country’s most beautiful stately homes and support Mam and Irene’s children, who were now all but orphaned, given their mother was dead and their father had absconded without so much as a forwarding address. Securing their future would be at the expense of her ever marrying. She sighed deeply. ‘The only way you could ever live in Holcombe Hall itself, Nell, would be to go into service like I did at fifteen.’

The little girl’s eyes widened. ‘Ooh, can I? Can I please?’

George studied his chicken drumstick. ‘I like the horses, me. If I get a job as a stable lad, can I live in the big house, too?’

Florrie shook her head. ‘No, love. You’d have to live above the stable block or in the coaching house with the other lads.’ She took a sip from the bottle of

homemade lemonade that her mam had included in the picnic basket. ‘But, if I’m honest, I think you’d do better to work as hard as you can in school and get normal jobs.’ She reached out and rubbed Nelly’s arm. ‘Wouldn’t you like to work in a shop? The post office, maybe? You could even be a nurse!’ She turned to George. ‘And you could be anything. A mechanic, maybe? Graham the chauffeur could teach you to fix cars, and then one day, you might even own your own garage – be your own boss.’

‘Could I be a pilot, like Lady Charlotte and that German feller she’s pally with?’ George got to his feet, spreading his arms wide, and started to run around the rose garden. ‘I could fly to the Americas and seek my fortune.’

Florrie chuckled. ‘Who knows? But just apply yourself in school. Being in service has a lot to recommend it – we’ll never go hungry or want for a roof over our heads – but only as long as me and Nana keep our jobs. And there’s lots we can’t do.’

Alice got to her feet and flung her arms around Florrie. ‘Don’t be sad, Auntie Florrie. Love you.’

Drinking in the pungent smell of the Derbac soap her mam had used to wash Alice’s hair, to ward off the headlice that were so easily passed on from George and Nelly’s school friends, Florrie held her niece tight. She pushed away imaginings of how her own children might look and feel and smell. Just be happy with what you’ve got, Florrie Bickerstaff, she reminded herself. It’s not perfect, but you’ve come a long way from the slums of Manchester. That’s worth something. ‘Love you too, chuck.’

That evening, when dinner had been served to the Harding-Bournes upstairs, she and Thom dined with the other staff at the oversized kitchen table.

‘By heck, that were a cracking pie,’ Thom told Cook. He slapped his stomach and rocked back on his chair, lacing his hands together behind his head. ‘Smashing spuds, too. Just what the doctor ordered after a day’s weeding.’ He reached into the breast pocket of his shirt and took out a pack of playing cards. ‘Who’s up for a game of poker?’

Cook pulled her chair in noisily and grinned at him, a mischievous glint in her eye. ‘Naturally, I’ll be defending my title.’ Leaning back, she rummaged in the drawer of the dresser and pulled out a packet of matches. ‘Stakes are high, Thomas.’ When she rattled the packet, it sounded full. ‘Question is, are we evenly matched in skill?’ She threw her head back and laughed heartily at her own pun.

Florrie watched, amused, as Sally rolled her eyes at her mentor.

Thom reached into his pocket and threw a packet of matches on to the table. ‘Sparks are going to be flying tonight, Cookie.’

Sally and Danny, the valet, both groaned.

‘Go on, then,’ Graham the chauffeur said. ‘I’m game.’

Miss Talbot, who had been sitting primly in the corner pushing the same forkful of pie around her plate for