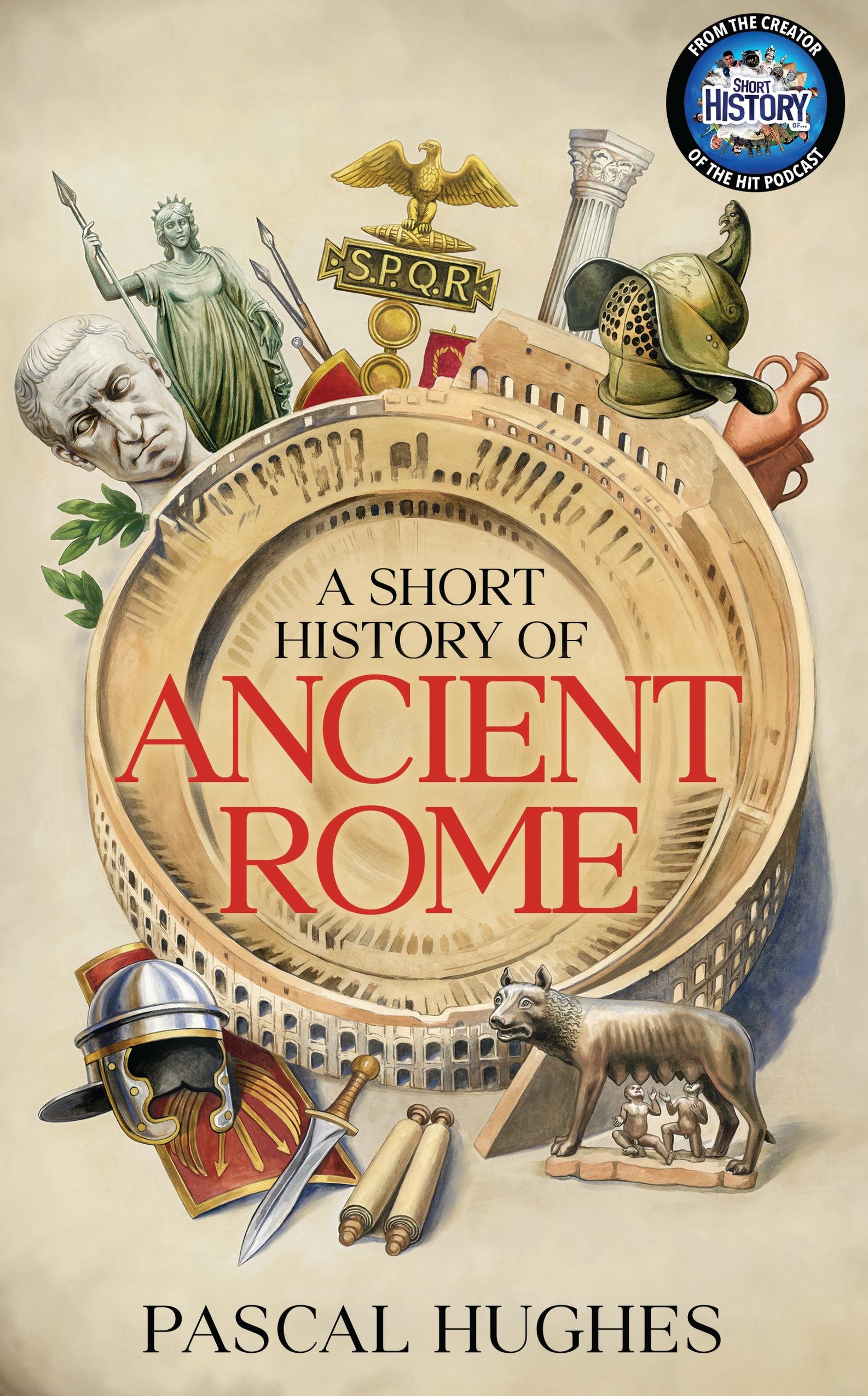

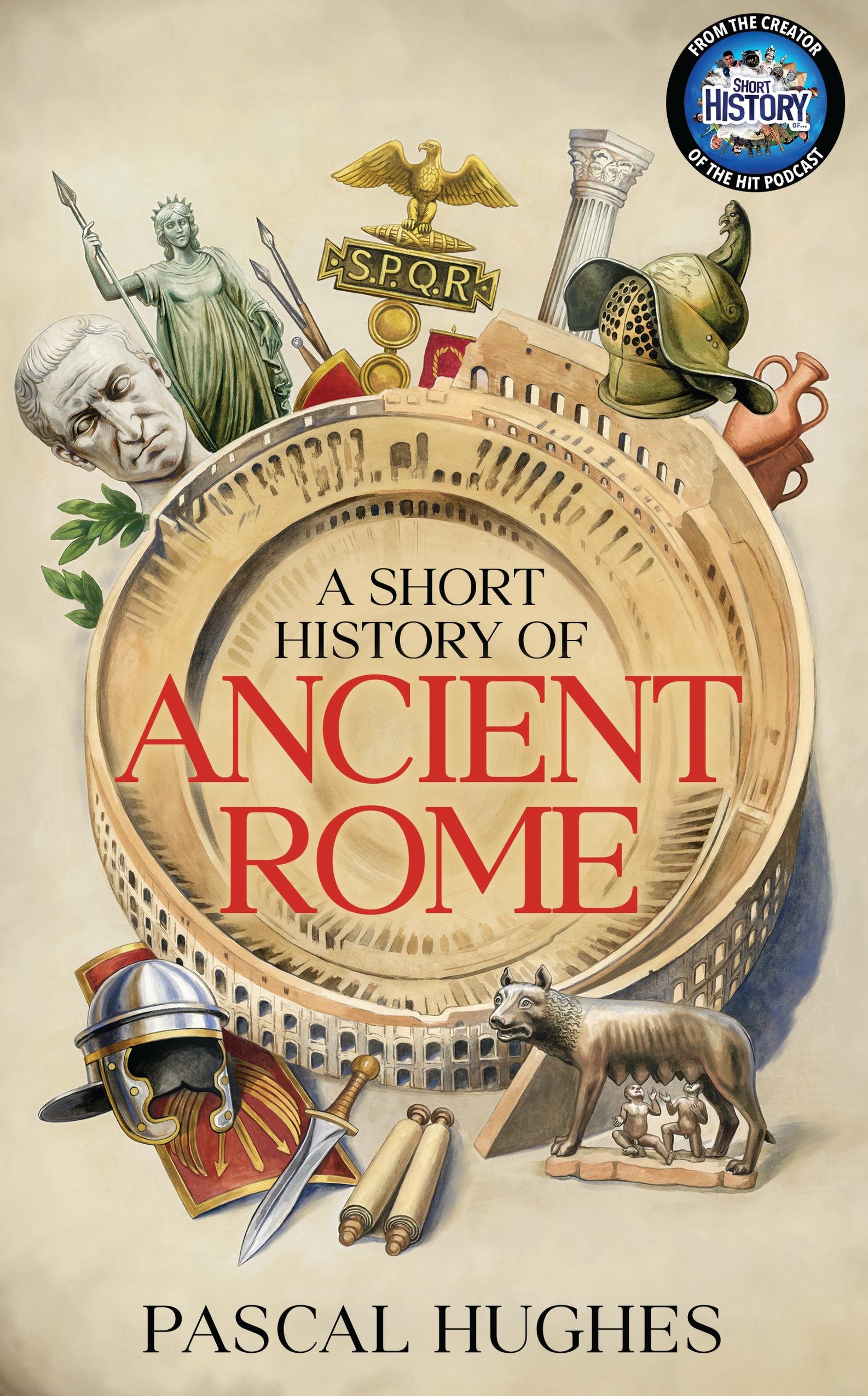

A Short hiStory of Ancient r ome

P AS c A l h ughe S

A nd dA n Smith

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW

penguin.co.uk

First published in Great Britain in 2025 by Bantam an imprint of Transworld Publishers

Copyright © Pascal Hughes 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Map bases by Lovell Johns Ltd.

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset in 11.1/15.2pt Calluna by Six Red Marbles UK, Thetford, Norfolk Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d02 yh68.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

iSBn: 9780857508140

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

c ontentS

18 Attila: Harbinger of Doom

Postscript: That Which Is Left Behind

Acknowledgements

m APS

Via Salaria

rome: city of seven hills

0

Camp of the Praetorian Guard

1000 metres

1000 yards

Baths of Diocletian

EsquilineHill

THE ROMAN EMPIRE

There is a famous scene in Monty Python’s Life of Brian in which the question is posed: just what did the Romans ever do for us? Gradually, a long list of that civilization’s accomplishments emerges, taking in everything from sanitation and roads to medicine and education . . . but notably not peace!

Beneath the humour lies truth. We in modern times owe so much to the Roman ancients. Virtually every significant aspect of our society traces a path in one way or another back to theirs, which dominated much of the world for a thousand years and more.

In the chapters that follow you will find the story of that civilization, from foundation to collapse. You will be immersed in a world that is both extraordinarily different from but curiously relatable to our own. Building on the blueprint of the Noiser Network’s chart-topping Short History of . . . podcast, this retelling of Rome’s remarkable story will bring its characters and events to life, with dramatized scenes built around the known facts and put into their wider context. I do not claim to cover every twist and turn (if I did, this book would be far too big to pick up), but by focusing on some of the most pivotal and interesting characters and events, I hope to capture the essence of what made Rome so important and why it continues to fascinate us.

But to begin this journey through the history of one of the world’s great cultures, we must first enter the realm of myth and legend . . .

1

Romulus: The l egend Begins

AD 476 – Germanic tribes invade Rome. The empire collapses.

AD 395 – Rome divides into two empires.

AD 272 – Emperor Aurelian stems the growing power of Zenobia in the East.

AD 126 – The Pantheon is constructed.

AD 117 – Under Emperor Trajan, the Roman Empire reaches its greatest size.

AD 80 – Emperor Titus opens the Colosseum.

AD 64 – The Great Fire of Rome.

AD 30 or AD 33 – Jesus Christ is crucified.

31 BC – Octavian defeats Mark Antony and Cleopatra.

49 BC – Julius Caesar crosses the Rubicon.

82 BC – Sulla becomes dictator.

264–146 BC – The Punic Wars.

509 BC – Rome becomes a republic.

AD 452 – Attila’s Huns invade Italy.

AD 306 – Constantine becomes Rome’s first Christian emperor.

AD 193 – Emperor Severus creates a military monarchy.

AD 122 – Hadrian’s Wall is built.

AD 96 – The era of the Five Emperors begins.

AD 79 – Mount Vesuvius erupts.

AD 61 – Boudica is killed following her tribal uprising in Britannia.

27 BC – Augustus becomes the first Roman Emperor.

44 BC – Caesar is assassinated.

73 BC – Spartacus leads his slave uprising.

218 BC – Hannibal crosses the Alps.

312 BC – Appian Way construction begins.

753 BC – Rome is founded.

It’s 753 Bc, halfway down the western side of the Italian peninsula. It’s a still day, the sky cloudless and blue. The rush of a nearby river fills the air. In the middle of the river sits an island, creating a natural ford. The surrounding land is hilly and well irrigated, a patchwork of lush greens, its fertile soils supporting all manner of flora and fauna.

Among a cluster of seven hills, one rises at the centre: it will come to be known as the Palatine. And right now, climbing one steep side of it in a tunic and leather sandals is a young man by the name of Romulus. Powerfully muscled and unconcerned by the sun beating down on his glistening skin, he passes a knot of lemon trees then heads for a rocky slope. Even as he scrambles for purchase, he makes swift progress, and soon he’s at the summit.

Hands on hips and breathing heavily, he turns to the south. Scanning another hill – the Aventine, notable for a cleft that runs through it – he spots the unmistakable form of his twin brother Remus, scaling the peak with equal vigour. Today these two young men have come here with an important destiny to fulfil.

Of royal birth, the pair have endured much in their short lives. Dynastic politics has seen them the subject of a murder

attempt in their childhood, and their claims to power continue to leave them vulnerable. It was around these hills many years ago that they were rescued from almost certain death. Now in early adulthood, they have vowed to found a city here. Their enterprising plan has, however, driven a wedge between them. Romulus is determined that he should rule the new settlement – but his brother is no less determined. It pains Romulus to be at odds with Remus, having shared many happy times with him and survived so much together. But some things are even more important than blood. Both are fit, healthy and ambitious, and there is no obvious superior candidate. So, they have reached agreement in a bid to bring their feuding to an end. They will leave the decision in the lap of the gods. They have come out here to take the auspices – that is to say, to study the behaviour of the birds in the heavens above in search of omens indicating who will lead the new city.

Romulus now turns his attention to the wide blue sky above him. Squinting against the bright sunlight, he can spot nothing of encouragement; but now comes the sound of enthusiastic shouting from Remus on the Aventine. He can just make out the shape of his brother peering upwards, gesturing to something above him. There, a large, dark bird is gliding on the breeze, great black wings occasionally flapping for uplift. A vulture. Then another, and another, circling above Remus, until there are six in total. Romulus cannot deny that this is a sign of divine will if ever there were one. But now a shadow moves over where Romulus stands on the Palatine too, and he looks up to see birds of his own. Not merely six vultures, but seven, eight, nine . . . he counts a dozen in total. Remus may have distinguished his omen first, but his is only half the magnitude of that of his twin.

A little later, when the sun is going down, Romulus meets with his brother and their bands of followers to discuss the signs. As far as Romulus sees it, it’s clear the gods want him to take command of the city. But Remus argues back, claiming the kingship as his own and rallying his supporters to his cause. It’s unclear who becomes aggressive first, but soon the disagreement turns physical. What begins as jostling among the two factions descends quickly into violence, with punches thrown.

Though the disagreement is far from settled, somehow the brawl is broken up – Romulus, at least, has more important things to do. Soon, he and his men set to work, building walls for the new city that shall be named in his honour: Rome. Remus, though, will not retreat from the confrontation. In a gesture of mockery, he bounds over the walls as they are being constructed. Affronted, Romulus is overcome by a fit of rage. With his supporters in close attendance, he makes for his twin, determined to force him into submission. Amid the ferocious tussle, Remus is struck down and mortally wounded – no one seems to know whether by his brother or one of Romulus’s supporters.

Romulus bears down over Remus, a man whose blood he shares and with whom he has overcome so much, but there is sign of neither compassion nor regret. His eyes still ablaze with rage, Romulus addresses his dying brother. Whoever dares scale his city walls, he declares, can expect to perish. Incapacitated, Remus looks back into his twin’s furious eyes, takes one final breath, and expires – the very first casualty of the towering pride and ambition of his twin’s city.

So, the historians of antiquity will have us believe, begins the story of Rome, destined to become perhaps the most powerful metropolis humanity has yet built. A city that begins

with a few walls rising from a hillside, its foundations established on pride and ambition at any cost – even violence, betrayal and fratricide.

origin Story

Tradition has it that Rome was founded in the middle of the eighth century Bc, but in truth the historical foundations for such a claim and for the stories about how it emerged are contested and frequently shaky. For the saga of Romulus and Remus and many other details of the city’s origin story, we rely on sources written hundreds of years after the events they claim to depict. The most important of these are by the historians Livy and Dionysius of Halicarnassus, who in turn relied in large part on earlier sources that have been lost to time, most notably a history of Rome by the chronicler Quintus Fabius Pictor, who lived in the third century Bc, but whose work has survived only in fragments. These writers left us accounts that were less concerned with the truth of Rome’s early days than with telling a powerful story to explain the Rome in which they now lived. Key to the story of Romulus and Remus, for example, is a connection the twins share with the god of war – something that explains and justifies the violence with which the city is founded, but also the enthusiasm with which its later inhabitants pursue territory and power. Romulus’s bloody conquest of his own brother lays a foundation for the crucial values of the society in which the historians setting down his story were writing: strength, expansion, domination and personal glory are greater even, in this case, than blood. All history is an act of interpretation, but the chroniclers of Rome’s early

years gave themselves extravagant room to interpret as they saw fit and embellish wherever they felt it necessary. So, the story of the city’s birth and emergence can be understood in the context of mythology as much as history. That is not to devalue the significance of these narratives, but we must recognize them for what they are – windows on how Rome saw itself and wished to project its image into the world.

But what do we really know about the region where Rome came to be built, in the time before Romulus and after him? According to his own legend, what exactly was his relationship with the gods? And did he ever really exist at all?

A city on A hillSide

The story of one of the greatest societies ever to exist on earth begins in a sunny region roughly midway down the boot-shaped Italian peninsula, its toes thrusting out into the Mediterranean. It’s a place of well-irrigated plains, flecked with springs and streams and rivers. Drinking water is plentiful and the soil is rich, supporting a varied agriculture. The mighty Tiber river, destined to become famous the world over, is navigable up to the island near where Romulus is said to have built the first city walls, some 15 miles inland. It provides access to the sea, with all the trading and communication advantages that offers. The hilly landscape that supposedly so appealed to Romulus and his brother offers natural defence, whether from armed invaders or the rising waters that result from sporadic flooding. It is as if these undulating slopes were made for the erection of fortresses and, in time, a formidable city.

There have been people on the peninsula since the Stone Age, and in the centuries preceding Rome’s foundation a complex web of different settled groups inhabits its expanse. Some of the most sophisticated settlements belong to the Etruscans, whose region, Etruria, comes to cover a large expanse north and south of Rome itself. Greek settlers have established impressive urban colonies of their own, such as Neapolis and Taras – coastal metropoles in the south of the peninsula. There are a great many more tribal peoples spread across the land in smaller settlements, including the Latins, prevalent in the area around what will become Rome. Graves here provide macabre evidence of human habitation in the immediate vicinity from at least 1000 Bc, with pottery shards

indicating human presence dating back perhaps as much as 500 years earlier. Nonetheless, it is not until the eighth century Bc – around the time of the legendary Romulus – that there are signs of more concentrated, permanent settlement.

divine BeginningS

Even as the archaeological record approximately coincides with the account of Romulus’s foundation of the city, there is little in the way of evidence to confirm the origin stories presented by Quintus Fabius Pictor, Livy and others. But these foundation myths are the ones that Rome’s civilization preserved, the proud tales they chose to base their identity upon and use to justify their position in the world. Stories, then, that we need to hear if we’re to understand the progress of the Roman state over the following thousand years.

The city’s origins, according to its later historians, can be traced all the way back to a Trojan prince by the name of Aeneas. Many generations before the days of Romulus and Remus, he escapes his burning city and sails to what is now Italy. Eventually integrating with the locals, he founds a city some miles from what will one day be the site of Rome. Power is passed down until eventually one of the ancient prince’s descendants, Amulius, overthrows his brother Numitor.

But after Numitor’s daughter Rhea Silvia is raped by the god Mars, she gives birth to twin boys, Romulus and Remus. Recognizing them as rivals for his crown, King Amulius has the boys cast into the flowing Tiber, where they are destined – he is sure – to meet a grisly end.

For Rome’s later citizens brought up on the stories of Romulus and Remus, this lineage proves a clear pathway

back to the gods. Mars, as the god of war and father of the twins, roots the state in a rich divine military heritage, while further back Aeneas is said to have been born of the goddess Venus. With such pedigree, no wonder Romans would come to consider themselves a cut above the mere mortals that inhabited the earth beside them.

the

Brotherhood

Fate conspires so that Romulus and Remus do not drown as their great-uncle hopes. Instead, as the Tiber’s floodwaters subside, the basket in which they have been placed washes up on the slopes of the Capitoline Hill. Still, not far away, apparent danger looms for the two infants unable to fend for themselves. A female wolf is on the prowl, having come down from the mountains in search of food and water. Her ears prick up at the noise of the babies crying. Following the sound, she steals closer, until at last she sees the pair, lying in the basket, vulnerable and helpless.

She approaches stealthily, her paws padding across the soft earth, until she is within striking distance. But she does not launch an attack. Instead, she lays herself down and offers them her mother’s milk. The boys eagerly drink. Before long a herdsman, a man named Faustulus, comes across the scene; he finds the she-wolf gently licking the heads of the twins as she suckles them. When she has finished, he scoops up the children and takes them to his homestead, presenting them to his wife, Larentia, to raise them.

Initially unaware that these are the lost grandsons of King Amulius’s deposed brother, the couple care for the twins. They grow into youthhood, spending their days chasing round the

forests and hunting. They are fine physical specimens and full of spirit too – so much so that their adoptive parents begin to wonder whether there might be something divine about them. When they tire of tracking animals, they go after robbers instead, stalking them and taking their booty, which they share out with the community of shepherds among whom the boys feel so at home. That is until one February day during Lupercalia, a festival of health and fertility. A posse of their bandit-victims has tracked the brothers down, intent on revenge. They lie in wait for Romulus and Remus, preparing their ambush. When they strike, the twins fight back. Romulus is able to escape capture, but Remus is not so lucky. He is taken by the bandits to King Amulius, and accused of raiding the lands of Amulius’s brother, the deposed former king, Numitor. Amulius hands Remus over to Numitor for suitable punishment.

Back at his homestead, Faustulus has by now pieced together the truth of his adoptive sons’ identities. He reveals to Romulus his belief that the twins are in fact princes. When Numitor learns that his prisoner has a twin, and then when he considers their age and Remus’s disposition – entirely devoid of the subservience one might expect from a shepherd’s son in the presence of royalty – he too concludes that the youths are likely the grandchildren he had long believed were lost to him. A plan is hatched in which Romulus and a small platoon of his young shepherd friends coordinate an attack on the palace of Amulius, supported by Remus and reinforcements sent by Numitor. Amulius is slain and the crown returned to Numitor. Now celebrated as princes, Romulus and Remus dream up their plan to build a city of their own, precisely on the spot where the she-wolf and the herdsman had come to their rescue.

the Birth of rome

Their fraternal unity is, however, shattered in the face of personal ambition. When the contest of the auguries fails to deliver a clear victor, Romulus resorts to the savagery that sees his brother killed. Romulus rules alone in the city named in his honour. The lesson to the generations of Romans that follow is clear: in the pursuit of personal glory, no sacrifice is too great.

Having made offerings to the god Hercules, Romulus sets about completing the fortification of the Palatine Hill and then commissions building on plots beyond it, anticipating the growth of the city. He also sets out a series of laws for his people to follow, while developing his own regal image so that his citizens – still relatively few in number – might better accept his authority. He clothes himself in finery and appoints twelve lictors, officials whose job is to attend him personally.

But it’s no good reigning over a great city if there is nobody there to rule, so next he attends to building a population. He invites refugees from neighbouring tribal groups to settle there, regardless of their social status. Word spreads about the fledgling city, including the fact that it offers asylum to fugitives and bandits, and soon Rome’s population swells with those dissatisfied with their prospects elsewhere. In this way, Romulus sets an early precedent for expansion by assimilation – something that will come to define the republic (and, latterly, empire) that will soon radiate from his city.

For the purposes of military service and taxation, he divides the population into three tribes, each administered by an official called a tribune. Each tribe is further subdivided into ten smaller groups called curiae, overseen by a curio. He

demands that every curia provides ten cavalry and a hundred foot soldiers (the commander of such a ‘century’ coming to be known as a centurion). He also establishes a council made up of a hundred senators, drawn from among the most prominent families, to help keep order and provide him with advice. As the years pass and the city establishes itself under Romulus’s rule, Rome comes to surpass many of its tribal neighbours in both military prowess and prestige. It even becomes a serious rival to those old antagonists of his predecessors the Etruscans, and other powerful groups, like the ancient local warrior tribe the Sabines. In the battle for expansion across the Italian peninsula, Rome is holding its own. But Romulus recognizes that a society made up mostly of men, however militarily adept, will get his state only so far. If his city is to thrive for more than a generation, he needs to find women to marry his soldiers and birth their children. And fast.

the rAPe of the S ABine Women

It’s a few years after the founding of Rome, and a black-haired Sabine in his late teens is taking a moment to rest in the shade of an olive grove. As well as his father, he is travelling with his mother and younger sister among a large contingent of his fellow tribespeople. He is weary from the journey they have made from their territory amid the Apennine Mountains many miles east of Rome, but he is keen to see the new city he has heard so much about. It’s still a little way away, but even from here he can see the impressive stone buildings, bright and new in the glorious afternoon sunlight. Springing from the hillsides, they are bigger and more imposing than anything

they have at home. He catches his father eyeing the scene with admiration too, but knows the older man would never acknowledge the neighbouring territory’s achievements. The rivalry between their peoples is too strong for that.

The rest over, the Sabine group now get to their feet, wrapping up the remains of the bread and stowing away leather water pouches in their horses’ saddles. Soon they’re on the move again, the boy rushing ahead at the front, struggling to keep a lid on his excitement. Because Romulus has invited them and several other groups from the local regions for what promises to be a spectacular new games, all in honour of Neptunus Equester, patron god of chariot racing. Though the boy’s father has his suspicions about Romulus’s motive, most of the tribespeople think it’s just a bid to raise his own prestige. And in any case, the gesture has been well received. Aside from the large crowd of Sabines, the teen can see a mass of people from other tribes descending on the city from all directions.

Over several hours this throng of humanity gathers at the location of the games. Many of the men arriving have come fresh from the battlefield, their bandaged wounds still healing, but few are willing to miss this chance to exercise rivalries in a joyful way, removed from the grit and gore of endless fighting. The boy can hardly wait for the signal that the festivities have begun.

Soon enough he hears a commotion growing around him. This must be it, he thinks. But there is none of the ceremony he has been expecting. Instead, only confusion, then panic – voices are raised, and everyone starts running. Looking up, the boy realizes why. Streaming down from Rome’s hills comes a small army of local youths, not much older than himself,

with weapons drawn. They set upon the Sabine men, and though his father tries to drag him away, the teen fights back. He throws his fists wildly in the melee, until he feels a hard thump to the back of his head. His knees buckle beneath him and he falls. Dazed on the dusty ground, he looks up to see his father being held by two Roman lads as another picks up his frantic sister and carries her away. She is, he realizes, just one of dozens of the invited young women to suffer this fate.

As suddenly as it began, the raid finishes. The Sabines left behind – grieving parents, brothers and husbands seething with a mixture of shock, heartbreak and incandescent rage – can hardly fathom the deception perpetrated upon them. They came as visitors in good faith, but leave as witnesses to an organized mass kidnapping, unwitting suppliers of brides for Rome’s young men. Nor are the maidens who have been seized any less indignant. Yet Romulus tells them the blame lies squarely with their own Sabine guardians, whom he says have rejected the Romans’ previously polite suggestions of intermarriage. He begins to appease some of the young women by granting them Roman citizenship and all the rights that brings forth. But among the various peoples of the central Italian peninsula his actions are regarded with fear and abhorrence. Envoys travel to the palace of the Sabine king, Titus Tatius, and plans are made for an attack on Rome.

Romulus relies on his army’s strength to repel the enemy on the battlefield, and in celebration of victory he consecrates a temple to Jupiter, the first such building in Rome. Nonetheless, the Sabines remain a force to be reckoned with and make further advances on the city, briefly seizing the citadel. The Roman army takes up a position in the valley between the Palatine and Capitoline Hills, poised for a defining battle.

To the kidnapped young women, this seems the worst of all worlds. By now time has passed and many of the women, willingly or otherwise, have become wives to Roman husbands and mothers to Roman children. If the Sabines win, these new brides of Rome will lose their families. If the Romans win, it will be their fathers and brothers who perish. So, with no consideration for their welfare, they race to where the men are fighting, throwing themselves between the warring parties, weapons flying around them. They plead for an end to the fighting, arguing it would be better that they themselves perish rather than be forced to live either as widows or orphans. An eerie silence falls across the battlefield as the combatants, commoners and leaders alike consider their words. The first tentative steps are made towards not only a peace but a treaty that unites the two powers under Roman sovereignty, with Romulus ruling alongside Titus Tatius. Not for the first time, nor for the last, Rome consolidates its position through a wily mixture of brutality, military heft and peaceable assimilation.

the end of romuluS

Romulus and Tatius rule in harmony for a time, until Tatius is slain while away from the city by enemies of his family. Romulus continues to enjoy military success, notably defeating the rival cities of Fidenae and Etruscan- ruled Veii, although the Etruscans remain a formidable opponent to Roman ambitions. Nonetheless, there is also cultural crossover between the two peoples, with the Romans for instance adopting the traditionally Etruscan toga and their love of gladiatorial battle.

Then, in 716 Bc, while Romulus is inspecting his troops, the sky turns suddenly grey. A thunderstorm brings in a dense cloud that wraps itself around the king, shielding him from the view of those on the ground. The legendary father of Rome is never seen again. At least this is the story as Livy tells it, although he concedes that it’s also possible Romulus has been murdered by a gang of disgruntled senators – a pattern, if true, that will be played out many times in Rome’s future.

Whatever the facts surrounding his death, Romulus is succeeded by a Sabine, Numa Pompilius, who develops the city’s religious and political institutions, as well as growing a cult around his predecessor. Among the citizenry, it comes to be accepted that Romulus has been raised into heaven by Mars himself – further evidence of the city’s military credentials and confirmation of its right to continue its expansion.

So ends the earthly story of Romulus, the purported founder of one of the great powers in history. But apart from the tales set down by Livy and his contemporaries, there’s precious little to say that he truly existed. Even so, interest in him is reignited almost three millennia later, in 2020, when a sixth-century Bc tomb is discovered in an ancient Roman temple claimed by some to be linked to Romulus. Although the discovery prompts academic debate, the veracity of his story remains a mystery that is unlikely ever to be decisively solved.

Nonetheless, the legend of Rome’s creation tells us much about its view of itself: why it believed in its divine right to conquer and colonize, how it came to grow a martial tradition, and how it looked to state- build through a combination of military force and political nous. These are all traits that have been shared by other expansionist political entities

across history. Yet there is something distinctly Roman in the celebration of Romulus, a man who kills his own brother. It not only establishes Rome’s potential for political violence and assassination, but, perhaps even more fundamentally, it leaves no doubt that the state always comes first, even above family loyalty. For Rome’s ancient chroniclers, it mattered less if their story of the city’s foundation was fundamentally true than that they produced a tale that could be read as the blueprint upon which the future glory of Rome was built.

2

lucR e T ia: Roman

Womanhood and T he BiRT h of T he Roman Repu Blic

AD 476 – Germanic tribes invade Rome. The empire collapses.

AD 395 – Rome divides into two empires.

AD 272 – Emperor Aurelian stems the growing power of Zenobia in the East.

AD 126 – The Pantheon is constructed.

AD 117 – Under Emperor Trajan, the Roman Empire reaches its greatest size.

AD 80 – Emperor Titus opens the Colosseum.

AD 64 – The Great Fire of Rome.

AD 30 or AD 33 – Jesus Christ is crucified.

31 BC – Octavian defeats Mark Antony and Cleopatra.

49 BC – Julius Caesar crosses the Rubicon.

82 BC – Sulla becomes dictator.

264–146 BC – The Punic Wars.

509 BC – Rome becomes a republic.

AD 452 – Attila’s Huns invade Italy.

AD 306 – Constantine becomes Rome’s first Christian emperor.

AD 193 – Emperor Severus creates a military monarchy.

AD 122 – Hadrian’s Wall is built.

AD 96 – The era of the Five Emperors begins.

AD 79 – Mount Vesuvius erupts.

AD 61 – Boudica is killed following her tribal uprising in Britannia.

27 BC – Augustus becomes the first Roman Emperor.

44 BC – Caesar is assassinated.

73 BC – Spartacus leads his slave uprising.

218 BC – Hannibal crosses the Alps.

312 BC – Appian Way construction begins.

753 BC – Rome is founded.

It’s around 509 Bc in Ardea, a town a little over 20 miles south of Rome and tucked inland a couple of miles from the Mediterranean coast. Ardea serves as capital of the Rutulian people, whose wealth and power have attracted the attention of the Roman king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus. So much so that he has recently ordered an attack on the town, keen to claim its riches as his own. However, the assault has been repelled and so Tarquinius is laying siege to it instead. He is confident that even if his attempts at a knockout blow have failed, he will succeed in strangling the town into submission.

In their entrenched positions outside Ardea, the days drag for Rome’s soldiers as they wait for the will of the defenders to break. Today a few high-ranking troops have been granted some respite, among them a man named Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus. He is sitting in the temporary quarters of his cousin, Sextus Tarquinius, the son of the king. Also present are several of Sextus Tarquinius’s brothers. Collatinus raises his cup to his lips and knocks back a slug of watery wine, then chews on a fig. With a few home comforts, spirits are high, and with their jaws loosened by drink, the soldiers get to talking about the women in their lives.