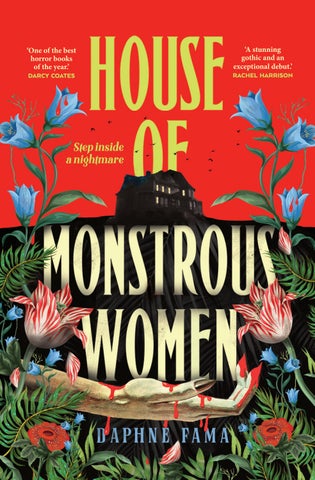

‘One of the best horror books of the year.’

DARCY COATES

‘A stunning gothic and an exceptional debut.’

RACHEL HARRISON

‘One of the best horror books of the year.’

DARCY COATES

‘A stunning gothic and an exceptional debut.’

RACHEL HARRISON

TRANSWORLD PUBLISHERS

Penguin Random House, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW www.penguin.co.uk

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published in Great Britain in 2025 by Bantam an imprint of Transworld Publishers This edition is published by arrangement with Berkley, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, division of Penguin Random House LLC

Copyright © Daphne Fama 2025

Daphne Fama has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

This book is a work of fiction and, except in the case of historical fact, any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBNs

9780857507969 hb

978085750976 tpb

Book design by Kristin del Rosario

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68.

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

To my mother. Without you this book wouldn’t exist.

To Harry Milton.

Thank you for believing in me.

To my father. Who passed on his love of words. And to you.

I dreamt of you and here you are.

February 23, 1986

TWENTY- FIVE years in Carigara and yet she still felt like a stranger in the plaza where she’d grown up. Women who should have been her friends leaned together, their eyes bright, their lips the same shade of rose red, given bloom by the communal lipsticks they’d swapped multiple times a day. Dirt-streaked children ran circles around one another. Men rolled dice on the street, throwing down coins as they made bets.

But all of them were watching her. She could see the way their dark eyes fl itted to their peripheries, glancing at her again and again. She could almost see their mouths shaping around her name. Josephine del Rosario. The daughter of dissidents. A political orphan. The heir to a crumbling house and a legacy of blood. Perhaps even worse than all that, a spinster in her midtwenties.

She was so sick of it.

The same rumors floated over the courtyard walls into her

house, month aft er month, year aft er year. Even the maids she’d grown up with, girls she’d always thought of as practically family, had started to speak with low, husky whispers. As if they were afraid their voices would carry in the dark del Rosario halls and worm their way into Josephine’s ears. But not once had anyone ever had the spine to say a word to her about it. Everyone in town seemed hell-bent on pretending she didn’t exist at all.

But today they were having a hard time of it, and Josephine smiled bitterly. She sat alone on the concrete bench of the jeepney stop, her long hair pulled back into a low bun, made shiny with coconut oil. Her father’s old suitcase sat beside her, and she wore her mother’s clothes. An ostentatious dress with bell-like sleeves and a long skirt, made of muslin dyed a subdued emerald. A decade out of fashion and a little too over-the-top for a ride deep into the countryside.

She could almost hear the wheels in their heads turning as they tried to fi nd out where she was going. It was rare for her to leave the del Rosario house unguarded. And with her brother in Manila, she didn’t have a single person to chaperone her out of town.

Her gaze skipped over the plaza, across the women slowly turning pork on iron skewers in market stalls, fi lling the air with the scent of sizzling meat. It was a smart business tactic to set up shop close to jeepney stops, when jeepneys were perpetually late and timetables were only vague promises. Plastic chairs scraped across the concrete nearby, and she glanced to her side to see the mayor of Carigara, flanked by his sons, settle at a white table only a few yards away. Eduardo Reyes held her stare as he leaned back in his chair, its plastic groaning, a satisfied smirk creeping across his wet lips. The woman at the stall rushed to put sweating glass bottles of San Miguel beer in front of him and his boys, popping their metal caps before rushing off to fetch a fi stful of pork skewers.

A decade’s worth of nightmares crept into Josephine’s throat, but she refused to be the fi rst to blink. He was the reason the del Rosario name was pronounced like a curse. In the light of a sweltering aft ernoon, he looked like any other old man on the plaza. Just a man grown round with age and luxury, his white shirt pulled taut over a sloping stomach, tucked into his black slacks.

He’d been lean when he orchestrated the death of her family eleven years ago. When her father had run against him on a platform that promised to push back against President Marcos’s martial law and oppressive taxation. The combination had proved to be a potent threat to the incumbent Eduardo. For weeks during the campaign, her father and mother, and their cousins and aunts and uncles, had all piled into a caravan of open-air trucks to drum up support in the neighboring barrios. Music would pulse out of their speakers, fi lling the streets. Her father would shout out his joyful promises to the crowds that gathered around the trucks, and her family would distribute bottles of beer and bags of rice. The bright promises and gift s garnered them enough goodwill to win the votes of the people, and every poll pointed to a del Rosario landslide victory.

But a week before the election, her father’s convoy had been rerouted by police cars and led outside town. The fi ne details of what happened next had never passed through anyone’s lips, but the gunfi re ended an hour aft er it started, and it left the sole coffi n maker of Carigara hunched and solemn for days. Josephine’s parents, her family, everyone who’d had the bad luck to be part of the convoy that day, were tossed into a pit that’d been dug days before, their bodies covered in a thin layer of dirt. It was almost insulting, how little they tried to cover it up. But the police were bought and paid for by Eduardo, and rumors swirled that it’d been Marcos himself who’d funded the guns and bullets that had torn her family

apart. She and her brother, Alejandro, had avoided the execution only because their mother had demanded they stay home to study. A cursory investigation had taken place, and a few triggermen had taken the fall. But Eduardo ran unopposed, and the roots of his political dynasty had only deepened since then. He and his sons fi lled the seats of the local office, following Marcos’s word like biblical law. She couldn’t tell if he just delighted in watching her squirm or if he was using her as a living warning to everyone else. Either way, no one had dared to run against him since.

Eduardo was a wart, but Marcos had been a cancer rotting the country from the inside out for the past two decades as he grew round and smug on his presidential throne. She could scarcely remember a time before he’d been in power—or a time when the world was still in love with the young and decorated war hero dripping with charisma and medals.

But with each passing year, the effect of his rule had only become more prominent. The country had become lean beneath rampant inflation and taxes. The dissidents, once loud and proud like her parents, had been silenced by death, coercion, or greed. But now hundreds of protesters, emboldened by Cory Aquino, were gathering in the streets in Manila, demanding that Marcos end his dictatorship. Aquino was the widow of Marcos’s most prominent political opponent, a man who’d been assassinated in full view of reporters. The protesters and the church had rallied around Cory aft er that, as if she were the Holy Mother given flesh, in the hopes that she’d deliver them from Marcos’s evil.

And yet that ferocious, hopeful spirit still hadn’t reached Carigara. Their little village, tucked between sea and mountains, was caught in the web of the past, drowning in the long shadows of Eduardo and Marcos.

There’s no way those protests will end without bloodshed, Josephine thought. President Marcos and his cronies like Eduardo had proven time and time again that a bullet could be an easy, consequencefree solution to most problems. It terrified her to think that Cory, small and always dressed in yellow, with a big perm and bookish glasses, might end up like her parents. Cory was too tender, too full of bright aspirations that the country could fi nd some happiness aft er so much pain.

“Josephine? What in the world are you doing out here?”

Josephine blinked and looked up to see a middle-aged man with a stooped back standing beside her. His age-soft ened face mirrored her surprise, and like her he was dressed too well for Carigara’s plaza. His thick polo, while perfectly becoming for a doctor educated in the city, didn’t suit the humidity of the day.

“Oh, Roberto. Good morning.” Her tongue stumbled over the greeting. If there were a list of people she didn’t want to see this aft ernoon, Roberto undoubtedly would have been second. He was the only person who seemed unfazed by the gossip that swirled around her, which kept everyone a lonesome but safe distance away. In fact, he seemed to have taken on a new, vigorous interest the moment she turned twenty. But any goodwill was lost by how close he insisted on standing beside her, how intent he was on trying to guide her life.

His fi xation made her anxious in a way that Eduardo simply did not.

She struggled to push the exasperation off her face. The older man clucked his tongue. “I wouldn’t goad him, Josephine,” Roberto warned, without once looking at the mayor, who watched them over a fresh beer. “It’s been a long time since that awful tragedy. But his sons seem quite content to follow in his footsteps.”

Josephine glanced again at the table, and at the two boys flanking their father. They weren’t much older than her, but they stared back at her with a stony coldness, like the cobras that made their homes in the graveyard.

“I wouldn’t dream of it,” she muttered.

“Good, good. Now . . . why are you dressed so lovely today?” His eyes fl ickered appreciatively over her, and she clenched her fi st around her suitcase’s handle.

Where is that jeepney? This was the absolute last conversation she wanted to have. And she hated the feeling of his eyes on her.

“I’m going to see my brother and an old friend.”

“Your brother? A friend?” There was a disbelieving emphasis on that last word, as if it was hard to believe that Josephine del Rosario still had a single friend left in the world. “Not Gabriella Santos? I thought you hadn’t spoken to her since high school.”

The disbelief in his voice was palpable, and she couldn’t blame him. Gabriella and she had been close as girls, but aft er the way things ended in high school, the two had barely spoken.

“Oh, she’ll be there, too. It’s someone I haven’t seen in a long time.” She chose her tone carefully, refusing to let the anticipation of seeing this old friend permeate her voice. She couldn’t let him know who else she was going to see. She was almost certain that he’d forbid it—as if he had the right to do so. It made her blood boil, the way everyone thought they could control her life, just because she was a young, unmarried woman. If she hadn’t been insistent on keeping the del Rosario house standing, a memorial and proud testament to her family and their legacy, she would have left long ago to join her brother Alejandro and Gabriella in Manila. But if she left , Eduardo would win. She could never accept that.

“Well, surely they don’t expect you to go to them by yourself?

Not without a chaperone?” Roberto asked, but it wasn’t a question. He sounded unconvinced, and his eyes narrowed as if trying to catch her in a lie.

Josephine tried to smile, but it came out strained and thin. If her brother were here, she was certain that he’d have sent the old man packing by now. But she could feel eyes on her, and the weight of her mother’s prim and strict upbringing. It was unacceptable for a young woman to raise her voice to her elders, especially to a man. More than anything, she wanted to snap. Instead, she reassured him. “It’s not far. I’m not going to Manila, just an hour or two north—”

“It’s not safe for a girl to travel by herself. I’m sure your brother didn’t ask you to come visit him all on your own,” Roberto protested. “You certainly can’t travel in such a dress by yourself. What will people think? What will they say? I can arrange for someone to accompany you. My nieces are around your age—”

Down the road, the jeepney rolled into view. An image of Jesus wearing a thorned crown had been painted across its side, his weeping face Josephine’s salvation. The jeepney pulled up to Josephine’s stone bench, and a line of people slowly disembarked from its open back door. Hope surged through her chest. Her hands tightened around the handle of her suitcase as she waited for her chance to flee.

“Here, we’ll go to the grocery store and call your brother together. He’ll understand,” Roberto continued, straightening, as if the decision had already been made. He laid a fi rm hand on her shoulder, fully prepared to lead her to where she needed to be. Josephine watched as the last passenger disembarked—a short, wiry old woman carrying a woven bamboo basket that contained two live chickens. The hens crooned soft ly, their eyes glassy and unblinking.

Looking at them fi lled her with a wild surge of panic. If she stayed, if she listened, she’d be trapped here. The moment the old woman was out of the way, Josephine pulled away from Roberto, darting away from his grip. Her free hand fumbled through her purse for a fi stful of centavos and silver pesos. She shoved the payment toward the driver.

“Please, kuja , take me to Biliran.”

The driver’s dark nose crinkled, but he took the handful of coins and dumped them into a cut-open Coke can, where they clattered with a dull symphony.

Roberto stood, open-mouthed, beside the stone bench she’d been on just a moment before. He approached the long, rectangular window of the jeepney, his eyes not quite comprehending that she’d simply gotten up and left .

“You can’t be serious, Josephine. This isn’t safe. Be reasonable.”

“I’m very sorry, Roberto, but I have to go,” Josephine replied. She wasn’t the least bit sorry. Instead, she prayed to every saint that the driver would push the pedal to the floor and leave him in the dust.

Roberto scowled and turned to approach the jeepney’s door in the back, as if he meant to drag her out with limp-handed force. In the front seat, the driver leaned out his window and spat betel nut juice onto the street before revving the engine of the old, repurposed military jeep. The jeepney lurched forward, sending up a puff of exhaust, and Roberto was fading into the distance by the yard.

He called out aft er her, but the driver had already switched on the radio. Bing Rodrigo’s mournful voice drowned out his shouts. Since Marcos had come into power, it’d seemed like every song on the radio was a sweet, melancholy dirge. And for once, Josephine found them tender, even welcoming.

Relief swept through her, and Josephine collapsed into the narrow leather seats, her shoulders slumping as if the weight of the world had fi nally slipped off her shoulders. Carigara rolled past the open window. First the markets, then the church, and finally the farms and their fields of rice. A new, buzzing excitement grew in her chest. It’d been years since she’d left Carigara, and she cherished every mile that grew between her and her hometown.

But more than that, she was excited, ecstatic, about her destination.

Gently, she pulled the letter from her suitcase. Its fi ne paper was already creased from how many times she’d read it. Her lips grazed tenderly across the letter. It smelled of fertile earth, of santol rotting between roots, of honey thick enough to drown in. She unfolded the letter, just to read it again.

Dear Josephine,

I’ve missed you so much. Nothing would make me happier than a reunion. Why don’t you come visit, and we can play games like we used to? And if you do, and you win, I promise to help you claim the future you’ve always hoped for. Alejandro and Gabriella have already accepted, and I deeply hope you will, too.

With tenderness, Hiraya Ranoco

It was taken as fact that the Ranoco family were witches capable of cursing and doling out blessings in equal measure. But there were darker, persistent rumors that they were more than that. That

they were aswang, creatures who looked like beautiful women during the day, and at night turned into shape-shift ing monsters who hungered for corpses and blood. She was certain that the rumors were unfounded, though a soft dread in the recesses of her mind told her that something wasn’t quite right with the Ranoco family. They were secretive and strange, sometimes even cruel. And Hiraya had led a parade of broken hearts through Carigara until a fi re sent the whole family fleeing back to Biliran. Josephine’s own broken heart had followed Hiraya there, and she wasn’t certain she’d ever gotten it back.

But there was more in the Ranoco house than her heart. Every letter she’d received from Alejandro in the past few months was scarce on details, bordering on skittish. He was so determined to be the man of the family, to strike out and turn their miserable legacy into gold. But she suspected things had not gone to plan in Manila, and neither he nor Gabriella seemed willing to tell her precisely what had happened. If she cornered him in Hiraya’s home, he’d fi nally have to answer her, and no amount of machismo and pride was going to stop her.

He couldn’t leave her alone and waiting in Carigara forever, guarding the del Rosario house by herself. She wouldn’t let him.

ONCE Josephine was free of Eduardo’s and Roberto’s dissecting stares, the tension in her shoulders fell away. Her hands fumbled for her mother’s silver compact mirror, and carefully she took in her own face. Her father’s dour eyes stared back, a harsh juxtaposition to her mother’s high, almost gaunt cheekbones. Carefully, she twisted the silver bullet of the half- used lipstick and painted her lips bright red. The lipstick was old—twenty years old at least. But like the compact mirror, it was more charm than cosmetic. It made her feel safer, braver. Like her mother was in the mirror with her.

But as she smacked her lips, her reflection shook with her hands. She was full of frayed nerves. Eduardo and Roberto had unsettled her, but Hiraya. The thought of Hiraya made her secondguess everything.

Lipstick, her hair, the dress. Was it too much? She’d never seen

Hiraya wear makeup. But she could remember vividly how Hiraya loved the singing starlet Elsa Oria, with her bold, pouty smirk. She’d cut out her picture from a magazine and pasted her image onto the wall, claiming the image to be “aspirational.”

Josephine snapped the compact shut and new passengers fi ltered on and off. Fashion meant something different here in these towns with vast swaths of rice fields and forest stretching between them. Styles that had been popular ten years earlier were gaining traction, and all around her were different iterations of T-shirts and harem pants, shorts and skirts. Bright jewel- toned emeralds and ochers. Little touches of America’s occupation interweaving with a national love for all things bright and colorful.

But if Hiraya’s letter was anything to go by, Josephine would bet money that the Ranoco house would have rejected most aspects of modern life. Even when the girls were children, Hiraya’s mother and aunt favored traditional remedies and hand-stitched clothes, their hands repeating for years the intricate geometric patterns that had been native to the Visayan islands tucked in the center of the Philippines. And some part of that seemed to have taken root in Hiraya, because it hardly made sense that she was enamored of their childhood games now that they were all well into adulthood.

But tagu-tagu had always had a certain allure to Hiraya. The game was nothing more complicated than hide-and-seek at night. And yet, even when they were children, it’d never really felt like a game at all. More like . . . practice. A rehearsal Hiraya would goad her and Gabriella and Alejandro into playing, as if they each had their role. They’d been barely seven when Hiraya had dragged them into it.

Josephine could almost taste the heady scent of rotten santol fruit, thick and sour- sweet on her tongue. The way the broken stems on that old jungle path had dug into her bare feet. Gabriella’s

screams jolting between the trees as Hiraya hunted her through the forest.

The game had terrified her as a child. It’d felt like life or death. And yet she almost missed it. They’d been so innocent then, and all too happy to follow Hiraya into the woods. Even Sidapa, Hiraya’s little sister, had tromped dutifully aft er them. Though she hadn’t been allowed to play.

“The way my family plays tagu-tagu is different,” Hiraya had explained, her mouth a serious arc, as she and the rest gathered beneath the ancient branches of a santol tree. In the distance, the Angelus bells rang, calling the faithful to church, and the sun had begun to slide beneath the horizon. A nervous thrill gripped Josephine’s heart. She knew her mother would beat her if she found her daughter had stayed out past her curfew to spend time with them.

“This is the Ranoco version,” Hiraya pronounced, full of swelling pride. “There will be two seekers, who will be the aswang. And two hiders, who will be prey. Sidapa can watch, since she shouldn’t even be here.” Hiraya shot an annoyed look at Sidapa, and Sidapa bent her head, hiding her face beneath her long sheets of black hair.

Sidapa had scarcely seemed like Hiraya’s sister at all. She had been too mousy, with narrow shoulders and lank hair. A shadow of her older sister. No one had stepped in to defend her.

“If the seekers are aswang, does that mean they get to suck the blood out of losers’ necks?” Alejandro had asked. He grinned at Hiraya, his voice fl ippant and teasing, his shoulders slouched. He was older than they were by a few years, and already too mature and grown-up for their games. He’d come only because Josephine had begged him. But Josephine could still recall, vividly, how she and Gabriella exchanged glances upon hearing his question. Even when she was a child, the rumors that the Ranocos were aswang were

omnipresent. But she’d never been brave enough to ask Hiraya outright what that meant. And, more importantly, if it was true.

“Aswang don’t drink living blood,” Hiraya had chided, rolling her eyes. “Don’t be stupid. They eat the living and the dead. But if you beat an aswang at their game, you get a gift . If the aswang catches you, you have to give them something in return. That sounds fair, right?” She didn’t wait for them to answer. Instead, they drew lots from broken twigs and the roles were picked. Alejandro and Hiraya would be aswang, and she and Gabriella would be the hunted. Gabriella had heaved a deep, bone-weary sigh that hadn’t suited her princess-soft face and looked at her.

“I’m not sure about this,” Gabriella muttered.

“It’ll be fun,” Josephine whispered, grabbing her hand. “Let’s hide together.”

Since that fi rst game, they’d played tagu-tagu countless nights in the forest, tumbling through the dark as if they were spirits tumbling across the land.

Her mother hated how much she adored that game, and how much time she spent with the Ranoco daughters. Perhaps she could sense the deep fascination her daughter already had with Hiraya and recoiled at the thought that Josephine might be a tomboy—a girl who liked girls. And yet, as much as Josephine admired her mother, as much as it wounded her to see the anger and panic in her mother’s eyes, she couldn’t bring herself to keep away. Perhaps the infatuation was genetic.

A dark memory twisted in the back of Josephine’s head. One she’d spent most of her life keeping away, so that it had a sort of dreamy, half-remembered quality. She’d seen her mother on more than one occasion with Hiraya’s aunt, the healer and fortune teller Tadhana. Tadhana was a stern woman with black plaited hair, and

she was handsome, even with the deep, sunken hollows where her eyes should have been.

Tadhana would come every full moon, and Josephine’s mother would welcome her into the backyard. From her room upstairs, Josephine could see everything. She’d stare through the window and watch Tadhana bathe her mother in herbal water. Water full of vines and leaves, tinted brown, as if it’d been taken from a swamp.

It felt wrong to recall how Tadhana’s fi rm, calloused hands would read the leaves stuck to her mother’s skin as if they were braille, and how her mother seemed to melt beneath her hands.

It was witchcraft . Tadhana was renowned throughout the coast as a talented manghuhula , a soothsayer who could read fortunes. But unlike the fortune tellers who clogged Manila’s Quiapo district, Tadhana didn’t lean on dog-eared tarot cards. She read the knots in animal entrails with her bare hands, prodded the recesses of scars that lay across arms and legs, divined meaning from broken bones scattered across tables. The blind, it was said, were the most talented at these arts. And it was rumored that Tadhana’s eyes had been taken so she’d be even closer to the spirits that helped her divine the future.

But this strange reading of water and earth seemed to be reserved for Josephine’s mother alone. And no one in the del Rosario family ever acknowledged it. Certainly not her mother, who put on bold airs of hating Tadhana and the Ranoco daughters while in public, and certainly not her father, who would refuse to look at her mother the day aft er a full moon.

She was certain her mother would be furious to see her in this jeepney, wearing her lipstick, her clothes, to see Hiraya Ranoco. Or perhaps she’d be jealous that her daughter would see Tadhana and she would not.

“Miss, when are you getting off ?” the driver called back, his voice clipped and rough, as if he’d asked the same question several times in a row.

Josephine lifted her head abruptly and only then realized how far they’d come. The pockmarks of civilization were gone, and now they traveled along a narrow road, with dark trees pressing in on them from either side. She was the last person on the jeepney.

“Kawayan, kuja. Is it far?”

The driver stole another glance, and this time she could see his brow wrinkle, his eyes narrowing into an expression she couldn’t read.

“You don’t look like you fi sh.” He said it like an accusation, and Josephine gave him a thin smile.

“I don’t. I don’t think I’ve ever touched a fi llet knife.”

“You’re going to the old Ranoco house, then.” It was a statement, not a question.

“You know them?” Her heart fell, even as she kept her smile afloat. Even aft er all these years, rumors shadowed Hiraya and her family like a persistent wraith.

“Everyone here knows them. You’ve got some future you’re chasing?”

So I’m not the rst to get that letter, Josephine mused.

“Don’t we all?” she asked.

“Sure, we all do. It’s human to sin. To covet and want. But everyone I’ve seen who goes to that house? They either go in and come back different or they don’t come back at all.”

Josephine barely prevented her eyes from rolling to the tops of their sockets. Small- town superstitions and urban myths. She forced a smile instead, offering teeth and feigned confidence.

“I go with God, and God protects me,” she reassured him, her

eyes drift ing toward the mournful expression of the Virgin Mary hanging from his mirror like a Christmas ornament. And just to lay it on a little thicker, she placed a hand on the rosary around her neck, silver and tarnished by her mother’s fidgeting.

“I’d question if it’s God that put you on this path, miss.”

She laughed, but the driver didn’t return it. He turned back to the road, but she caught him sneaking periodic glances at her in his mirror, as if she’d turned into a brief, ephemeral exhibit instead of a passenger.

Silence traveled with them until they reached the stop outside Kawayan. He didn’t respond to her thank-you, and the moment she stepped out he was gone, the jeepney spitting dirt up into the air as it spun around and headed back toward civilization.

She was happy to see him go, and took stock of her surroundings. She could see Marcos in every road and house before her. Carigara had grown thin, but Kawayan was at death’s door.

The fi shing village was just a fraction of the size of Carigara, and it was sustained only by the fact that the ocean and its bounty were plentiful. But the cement houses were topped with rusted roofs, and the sari-sari corner stores were all closed. No one could afford to stock the shelves, with inflation making even basic goods nigh inaccessible.

If Marcos stayed in power, the town would collapse to its bare bones. But tied around the cement pillar of the jeepney stop was a yellow ribbon. The hallmark of Cory Aquino and her followers. It was a bold statement, especially in a town small enough where nothing was ever truly anonymous. A small spark of hope lit in her heart.

Josephine moved toward the ocean, following the languid, irregular screeches of ocean birds. The ocean waves beat against a

narrow comma of a shore, its sands dark and kelp-lined. A stubby cement pier stretched out beyond the reach of the town.

But Josephine’s eyes were drawn to the craggy rock cliff and the alcove carved into it. Within it, a statue of the Virgin Mary stood. Decades standing beside the sea had caused the statue’s face to be worn away, leaving craters along her eyes and cheeks, smearing it until the divine mother’s visage was a mass of mottled stone. Her hands, which Josephine was certain would have been pressed together in prayer, were gone. Lost to the elements or worse.

Grotto shrines were common, but she’d never seen one so old or so decorated. Votive candles had been burned nearly to their bases. Piles of flowers, their petals spilling across the stone floor, covered the bottom of the shrine’s alcove. Coins glittered among the darkened splashes of color, along with bits of tack.

I should o er something. Anything.

The thought rang out in her head, tinged by something desperate and superstitious. She fumbled through her pockets and mentally kicked herself for giving the driver every last peso. But she felt certain that leaving without giving the statue an offering would be a terrible mistake. She fumbled at her fi ngers and took off an old gold ring. It had belonged to her mother, the way almost everything she owned did.

And it was with reverence and reluctance in equal measure that she laid it at the statue’s feet, on the bed of wilting flowers.

“O Mother of God, I stand before you sinful and sorrowful. I seek refuge under your protection. Don’t despise my pleas, we who are put to the test, and deliver us from every danger. Amen.”

Even as the old prayer fell from her lips, it felt shallow. It’d been years since her heart had been moved by the glory of God. Not since her parents had been gunned down all those years ago. Not since

the day she’d seen them laid to rest in twin white coffi ns flanked by half a dozen more. She could recall vividly the eyes of her brother as they followed the procession to the graveyard. His dark eyes were wet with unwept tears, black and determined. That was the day he’d become a man. It’d been thrust on him all at once, and he had taken on the role with a solemn dignity, rising to become the man of the house.

How could God lay such a burden on him? How could God steal their parents and refuse them any hope for justice? But still she lifted her eyes to the hollowed-out crevices of the Virgin Mary’s face and tried to fi nd solace in it. There were too many blessings here for a fi shing town. Especially one so desolate as this.

Had they all come here asking the Virgin for blessing and protection before making the trip to the Ranoco house? How many games had Hiraya and her family held in the time since they’d left Carigara? The driver had made it seem like there was an endless stream of people playing the Ranoco game for wishes. And these offerings, abundant as they were, seemed tinged with desperation.

Questions swirled in her head as she turned back to the pier. Its stone was battered and chipped from countless storms. But there, tied to a thin rope, was the small, motorized bangka boat Hiraya had promised.

She’d seen the fi shermen in Carigara gliding through the still morning waters on these boats, using nothing but the sputtering engine and an oar to steer. And, while she had no experience, Ranoco Island was only a mile from Kawayan. With a hand shielding her eyes from the glare on the waves, she could see it from the pier.

The island rose from the dark waters, precisely as Hiraya had described it to her when they were children. Just a few miles across, with thick trees covering it, so that it looked like a turtle’s

seaweed-covered back. Its craggy, black-rock edges made it a hostilelooking jut of land. But if she squinted, she could see another pier abutting a dark beach.

“God help me not drown in these still waters,” she muttered as she laid her bag on the bench. She unmoored the boat and, aft er some scrambling, managed to tilt it in the island’s direction with the single oar. Once she got the motor going, she was zipping across the waters, salt spray stinging her face. And for a brief, terrifying moment, between the islands, on the dark waters, she felt free.

She reached the beach faster than she expected and gracelessly disembarked, the shallow waters turning the edges of her dress heavy. Grunting, she tugged the boat by its rope onto shore, bringing it to rest by a twin boat laid out on the sand, a yard away. Two sets of footprints led away from the boat to the beach, dulled and swept a little by wind.

She stared at the set of prints for a moment, a rush of excitement and anxiety and anger tangling in her chest. She hadn’t heard from Alejandro or Gabriella for the last few months, though that wasn’t so unusual. The protests had slowed letters and packages down to a trickle—if they ever made it to their recipients. She was lucky to get updates from Manila at all, with the protests and blockades that stretched between the capital and her little tucked-away town.

But it still struck her as strange that they’d come to the Ranoco house now, aft er all this time. Gabriella had always been a skeptic about traditional medicines, the spells and curses, but Alejandro waffled between believing in the superstitions their mother had taught them and pushing it all away.

He must be desperate, to drag Gabriella all the way out here. What could have happened in Manila?

She knew the answer wasn’t anything good. When Alejandro

had left for Manila all those years ago, he had the fi rm, indomitable look of their father. But through his and Gabriella’s periodic letters to Carigara, she’d pieced together the truth. He’d spent an untold fortune of their shared inheritance trying to follow in their father’s legacy, going to law school and eventually trying to become a politician.

What followed that was business aft er failed business, and letters that had become increasingly cryptic. No one wanted to worry her, and her increasingly insistent demands to know what was going on had been danced around if not outright ignored. She didn’t care if her brother was trying to protect her. He was the last family member she had, and she hated knowing that he was enduring the worst of Manila without her. And no matter how she begged, he seemed insistent on staying.

This is where the money is was all that he’d write. I’ll stay until I make back everything I lost.

She trod toward the thick, encroaching jungle, the gray sand giving way to dirt, her hand tight around her suitcase handle. A well-worn path stretched out in front of her. A dark, empty corridor of matted leaves and creeping vines that unraveled into the shadowed corners of the island. This was the only mark of humanity. The rest was untamed and wild.

Gnats accompanied her intrepid steps into the jungle like a halo around her head, but through their mist she spied the shiny black gleam of beetles through the leaves. Bees, more black than yellow, crawled across rotting wood, carrying pink morsels in their mouths.

She was no stranger to insects—how could you live in the Philippines and be a stranger to them? But there were so many here. The forest squirmed with them. And they seemed to have no fear of her as she dragged herself up the well-worn path. Instead, they

seemed to watch her with dark, almost intelligent eyes. Like shards of clever obsidian. It unsettled her. It almost made her yearn for the stares in the plaza. She hated Eduardo and Roberto, but at least she knew what they were thinking.

The gnats grew bolder the farther up the trail she went. But there was no swatting them away. They were persistent, feasting on the sweat of her nape, taking sly kisses where they wanted them. She didn’t dare open her mouth for fear they’d crawl inside.

The trail swept upward, the jungle thinned, and the path widened. She could see the fi rst few shards of blue sky and, beneath it, Hiraya’s home. The Ranoco house.

This? This is where Hiraya lives? The shock of the place was enough to root her where she stood, the unease of the insects for a moment forgotten.

She’d seen pictures of President Marcos’s house, the ostentatiously named Malacañang of the North, and had thought that a decadent aff air bordering on gaudy. And yet here before her was a house more grandiose, more sprawling than anything Marcos and his insatiable appetite could even dream of.

The Ranoco house should have been ostentatious, but it wasn’t. You wouldn’t call an animal vulgar, and the house seemed as if it’d been born of the blackened soil of the island, though it was structured in the style of a bahay na bato, like Josephine’s own home. Its fi rst floor was volcanic stone covered in lichen and fat moss. The second floor was dark wood, complete with generous baroque wood carvings flanking the windows.

But where the wood and stone were ageless, the window lattices were fi lled with yellowed capiz shells that turned them into countless jaundiced eyes. Dozens upon dozens of eyes, like an obese, ancient spider, its gaze unblinking and patient upon her. Josephine

shook the sticky, foreboding thought out of her head and bit her lip hard when the feeling refused to leave her. Instead, she tried to see where the house ended.

But it stretched to either side, its dark wood blending with the shadows and vanishing into the jungle, as if it had no end. Aging stone walls marked the edges of what might have made up a courtyard. But beyond them were the remnants of charred, rotting wood. The house had somehow been bigger once. A fi re had razed it to the ground. Josephine bit her lip again. Fire and the Ranoco family. They seemed to chase each other.

Gently, she edged toward the house, following the trail of burnt, charred wood along its perimeter. The night the Ranoco women had left Carigara for good had been seared into her memory. It’d been only a week aft er she and Alejandro had laid her parents to rest. She’d been sleeping fitfully, her dreams haunted by gunfi re and shallow tombs, and lungs full of dirt and blood. But Alejandro had woken her up with a knock at the door, telling her not to leave her room. There’d been a fi re at the edge of town, and he was going to see if he could help. He was still just a boy, but he’d already taken on the mantle of the man of the del Rosario house, and he’d locked her in her room for good measure.

But that had done nothing to stop her. She’d gotten up in an instant and slid open her window to look out over town. A black, angry plume of smoke rose miles away, and she’d known instinctually that it was the Ranoco house.

Someone had set it ablaze. She had no doubt about that. The fear that had shook her in that moment was so deep that it worked its way into her soul, and she’d broken out in a cold sweat. Her world had shrunk so viciously in the span of days. She couldn’t bear to lose Hiraya, too.

She’d thrown her leg over the ledge, determined to fi nd Hiraya herself, and scrambled down the wood and coral-stone rock of her family home. She reached the earth and, barefoot, she had run into the empty streets. There, two silhouettes stood at the del Rosario gate as if they’d been waiting for her.

“Hiraya? Sidapa?” Her voice croaked, surprised and full of relief as she stared at them through the metal bars.

But something about the sisters kept her rooted in place on the other side of the gate. Hiraya stood rigid, her shoulders squared. Sidapa stood limp beside her sister, Hiraya’s hand a vise that kept her in place. Sidapa’s clothes were singed, her hands pink with fresh blisters, and she smelled undeniably of kerosene. The pity that Josephine had always nursed in her heart for Sidapa twisted. A small thought had kicked in the back of her head as she stared at the younger Ranoco sister.

She’s done something awful. “Is everything—is everyone okay? Is Aunt Tadhana, your mom—” Josephine asked, uncertain if she wanted the answer.

“Aunt Tadhana is fi ne.” Hiraya cut her off, her voice clipped and struggling to pass through her clenched jaw. “Mom is . . . Aunt Tadhana is going to help her. She’ll make it okay.”

The silence that stretched on for a moment longer told Josephine everything she needed to know about Hiraya and Sidapa’s mother.

“Sidapa and I have to go,” Hiraya whispered, and her voice had turned soft and wet. She laid a hand against the bars, then rested her forehead against it, staring at Josephine through them. She looked lost and terribly alone. “We’re leaving for Biliran tonight. Now. We can’t stay here. But I wanted to see you before we go. I wanted at least to say goodbye.”