MICHAEL CALVIN WITH NAFTALI SCHIFF

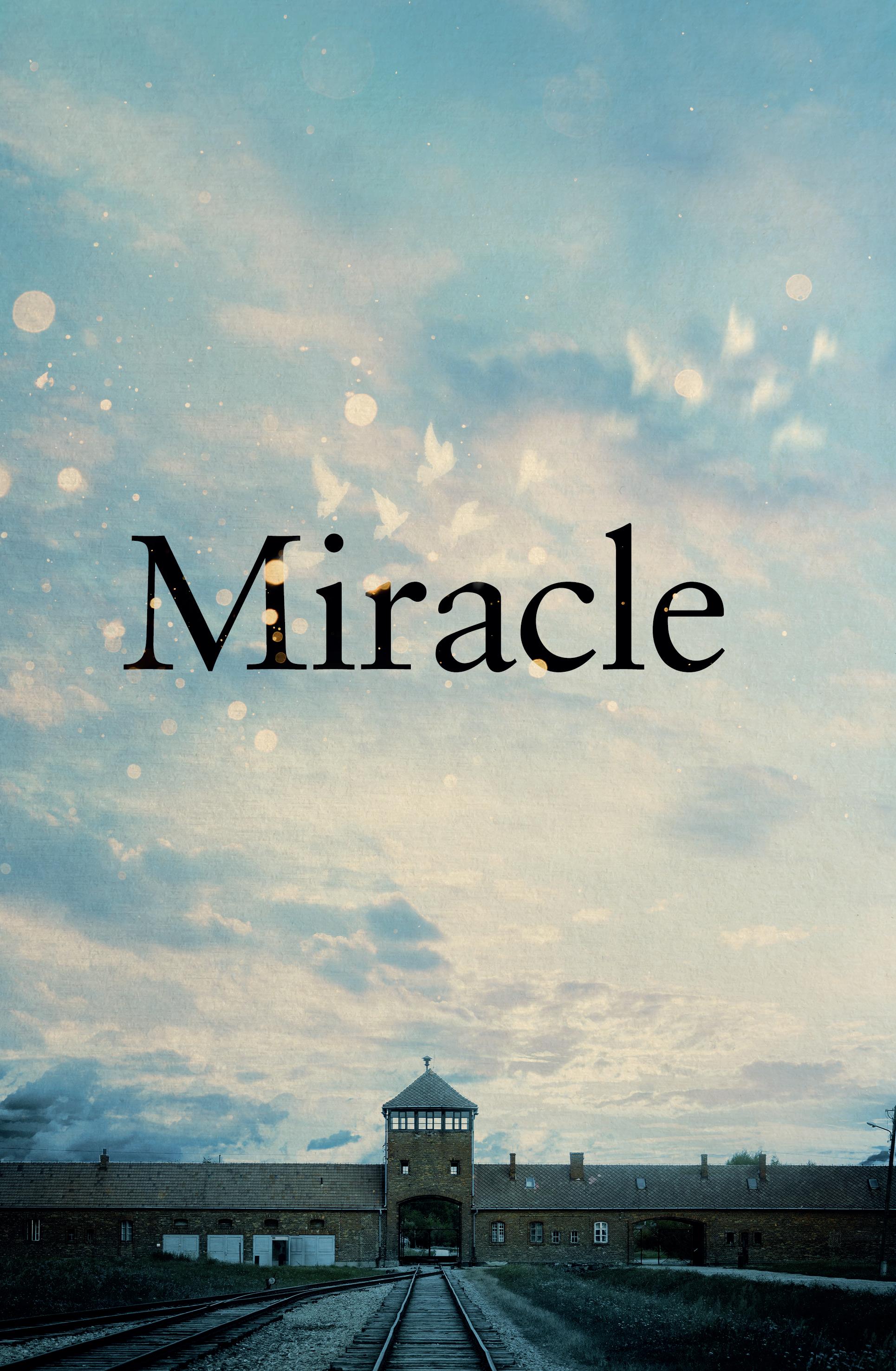

The Boys Who Escaped the Gas Chamber in Auschwitz

The Boys Who Escaped the Gas Chamber in Auschwitz

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW

penguin.co.uk

First published in Great Britain in 2026 by Bantam an imprint of Transworld Publishers 001

Copyright © Integr8 Communications Limited and JRoots Limited 2026

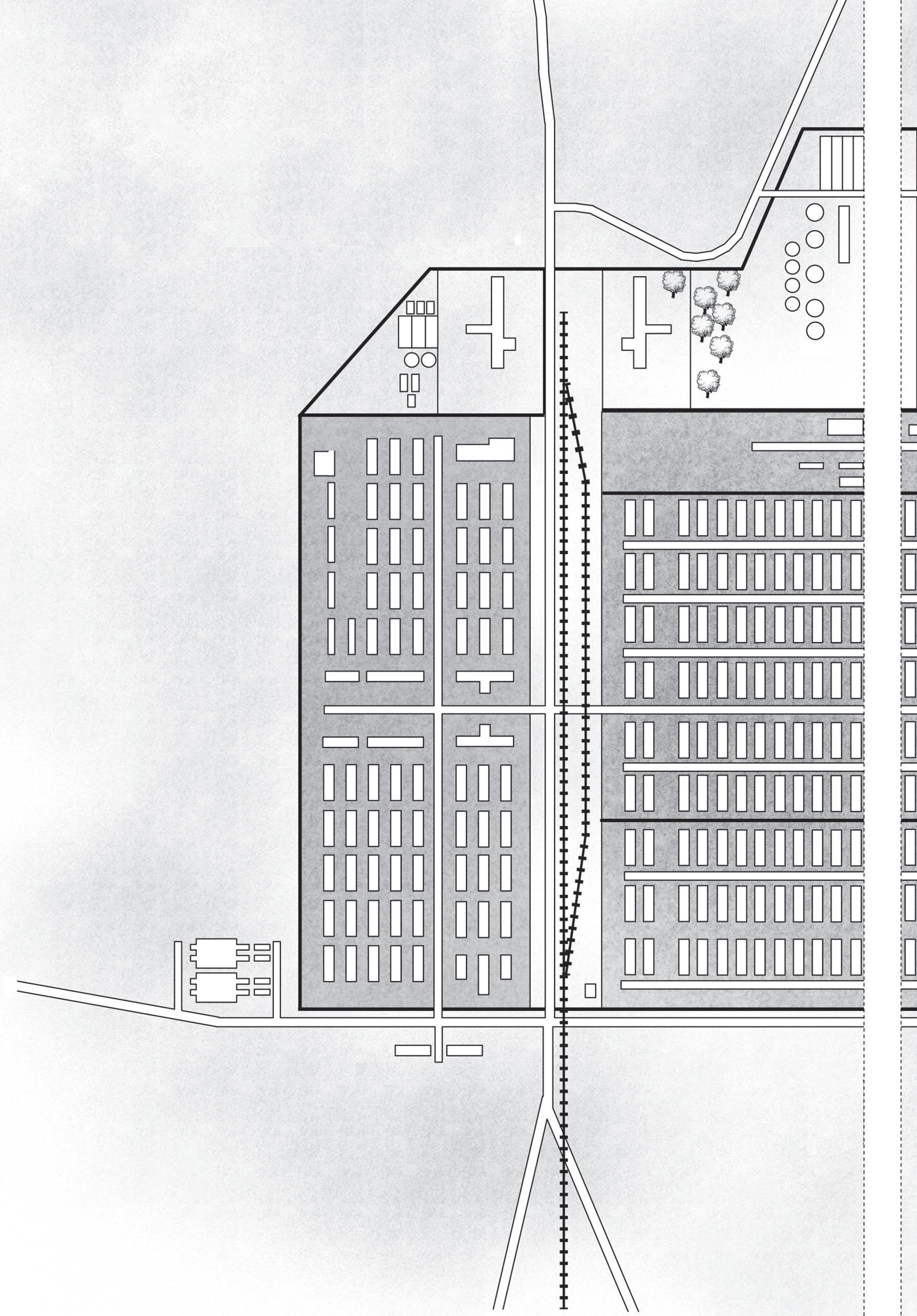

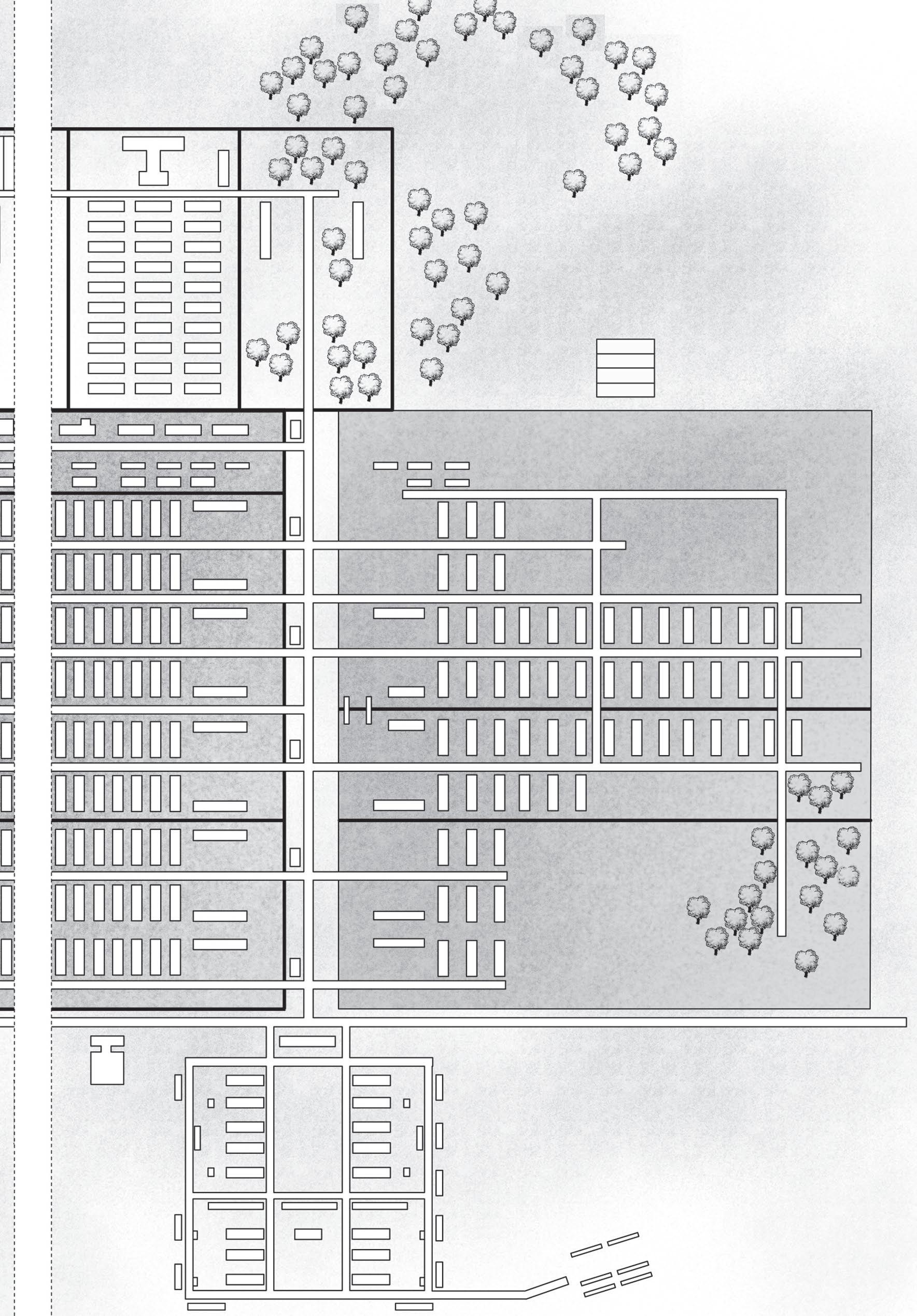

Map drawn by Tony Richardson at Global Creative Learning

The moral right of the authors has been asserted.

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset in 12/15.5pt Minion Pro by Six Red Marbles UK, Thetford, Norfolk Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBNs:

9780857507891 (cased)

9780857507907 (tpb)

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

As Jew, and non-Jew, sharing a story of hope and resilience in the darkest moments, we dedicate this book to our grandchildren. May they use the lessons of the past to build a better future.

‘There’s no survivor who didn’t experience absolute miracles.’

Yaakov Yosef Weiss

Gas Chamber / Crematorium II

Gas Chamber / Crematorium III

Gas Chamber / Crematorium IV

‘CANADA’

Gas Chamber / Crematorium V

camp extension)

A blind man sits, supported by grey cushions, in a bay window on the top floor of his London home, marking time with his left foot as he sings songs of remembrance. Hershel Herskovic is approaching his ninety-eighth birthday, but when he throws his head back, and his face softens into a full-toothed smile, he exudes the spirit of the rebellious, mischievous child he once was.

Naftali Schiff, one of the world’s leading collators of Holocaust testimony, leans forward towards him, as if in the old man’s gravitational pull. I am to their right, perched on the edge of a two-seater settee, feeding in questions that are answered in a mixture of Yiddish and English, joy and sorrow, reflection and urgency.

On this hot June afternoon in 2024, when the sun, filtered through net curtains, dapples a patterned mustard carpet, and the sound of children at play rises from the street below, we are both aware we are touching history. It has taken Naftali nearly twenty years to reach this point in confirming details of the Holocaust’s last great untold story.

He believes Hershel is the only living survivor among fiftyone boys reprieved from the gas chamber at Auschwitz-Birkenau on Simchat Torah, one of the most festive days of the Jewish calendar, which fell on 10 October in 1944. That something so

life-affirming, so miraculous, can happen amidst such monumental evil is simultaneously sobering and inspiring. Hershel regards it as providential.

Hungary was the Final Solution’s final frontier. Hitler was forced to wait a year before his plans for an extermination campaign there were put into operation between May and July 1944. The Second World War was being lost, yet some 424,000 Hungarian Jews were deported in those months to Auschwitz-Birkenau. A further 140,000 were murdered later in the year. In Budapest thousands were shot on the banks of the Danube and their bodies thrown into the river.

Heinrich Himmler, the principal architect of the Holocaust, set the Auschwitz command structure a minimum target of 5,000 deaths a day, but, though precise figures are hard to come by, it is thought four times that many were killed when the annihilation programme was at its height. Four crematoria operated ceaselessly, and additional bodies were burned in open-air pits.

Eighty years later, in that top-floor room in London, lined with leather-bound books of scriptures, written in braille, Hershel Herskovic would reflect, with a crushing weight of desolation, that ‘the Germans were determined that no Jews would be left alive’.

He was one of 800 Hungarian Jews, largely aged between thirteen and seventeen, who were marched to Crematorium 5 by twenty-five bayonet-wielding SS men. They were forced to strip, then herded into the so-called bathhouse in a killing field where around a million Jews, and another 120,000 ‘undesirables’, spent their final moments in unimaginable agony.

Victims simply do not walk off the gallows when the noose is around their neck, yet for the fifty-one boys who would reemerge this was its equivalent. The Sonderkommando, Jewish prisoners who postponed their own execution by disposing of corpses, crushing bones and spreading ashes, had closed the

vents. Dr Josef Mengele, the Angel of Death, was primed to oversee the release of Zyklon B hydrogen-cyanide gas pellets into the chamber.

The heavy front doors were being closed when three German officers, including another infamous SS doctor, Heinz Thilo, arrived on motorbikes, and ordered the evacuation of the chamber. They selected fifty boys to unload and plant a consignment of potatoes, which had arrived in the camp’s railway sidings from Greece.

They were lined up in rows of five in such haste that the guards did not notice an additional boy, who had hidden in a pile of discarded clothing before sneaking into the line. They were ordered to dress quickly; Hershel did so in such a hurry that he selected two right-footed shoes.

Their doomed companions were driven back into the chamber, to meet their fate. The last words they heard were uttered by SS-Obersturmführer Johann Schwarzhuber, the officer who oversaw the gassing programme and would later be executed for his war crimes. One of the reprieved boys, Yaakov Yosef Weiss, never forgot the venom in his voice: ‘Werfen sie in den Ofen’ – ‘Throw them into the oven.’ One boy chose suicide and threw himself at the electric fence.

This is a story of contrasts and contradictions, of hope and horror, of faith, fate and fortitude. It features inhumane cruelty and human kindness, and begs the question what we, in a subsequent generation, would do with a second chance at life. In an age of denial and disinformation, the story emphasizes the sanctity of memory.

It is a cross between a morality play and a detective story, and has, as its centrepiece, the only recorded instance of a group of Jewish prisoners being removed from a gas chamber and given the chance to live. Even for someone as well versed in the folklore of the Holocaust as Naftali, its drama ‘hit me full in the face’.

He had initially heard of the legend of the fifty-one in the late 1990s, through one of his earliest contacts among the survivors, Eva ‘Bobby’ Neumann. She had settled in Manchester and continues to provide a thought-provoking perspective on her experiences in Auschwitz-Birkenau. Nevertheless, Naftali was not specifically seeking to tell their tale.

As a Rabbi, community leader and educator, his principal motivation in taking the testimonies of hundreds of survivors was to provide a link to a younger generation. He sought to influence through the insight of those who had faced the ultimate evil, and who posed a profound question that has renewed relevance in an era of increasing antisemitism.

‘It’s complicated to be a Jew,’ he reasoned. ‘The post-Holocaust generation saw that. In the drive for prosperity in the latter half of the twentieth century, many Jews felt they had earned the right to raise a generation in comfort and pleasure, so it was no wonder they lost their religion. They asked, “Where was God in Auschwitz?” I was fascinated to understand why some people who were there, who saw their family and friends murdered, would want to return to their faith, or even to live lives of moral virtue.’

The question is sociological as well as theological. It touches on the essence of humanity, and the importance of heritage. Time is a tyrant; gradually, the voices of the Holocaust are being stilled. It is imperative that they are captured, for future generations, before they are silenced completely.

As a non-Jew, I feel a special sense of responsibility to protect the authenticity of memory. When you sit with these men and women in their twilight years, they have nothing to hide. If they like you, they will tell you. If they feel you are impertinent, or superficial, they will not camouflage their feelings.

I first came across Naftali when he introduced me to Josef Lewkowicz, a survivor of six camps who subsequently hunted

down one of the Second World War’s great monsters, Amon Göth, commandant of the Płaszów concentration camp. Collaborating on Josef’s Holocaust memoir remains one of the most rewarding personal and professional experiences of my life.

I identify with Naftali when he characterizes survivors as the greatest teachers, because of their extreme humanity. They have looked death in the face, and escaped its grasp. They have no fear in living life, and of passing on that freedom to their children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Speaking of whom, the extended families of survivors whose first-hand accounts of endurance are woven through this book total more than 1,000 people. All owe their existence to fate; if those three SS men had arrived on their motorcycles a minute later, they would not exist.

The fifty-one boys were products of an ultra-Orthodox upbringing, and shaped by the inherited disciplines of their faith. We will follow them from childhood, through incarceration and tragedy, to rebirth, adulthood, old age and death. Their lives, long and successful, are elevated from whispers and myths by the diligence of Naftali’s research, and his affinity with his subject.

He runs a network of charities from two office blocks in North London. In one, he organizes educational programmes for sixtyfive schools and twenty-three universities, including visits to concentration camps by youth groups and trainee leaders. In the other, he oversees outreach work and a study centre.

When I last visited, on a grey late-spring day in 2025, the ground floor was given over to a foodbank that fed 1,700 members of the local community. The first floor was set aside for the study of Jewish texts; while writing this book I often summoned the memory of two young men, their heads inches apart across a small desk as they earnestly discussed the significance and integral meaning of the texts spread out before them.

They were pulling at the threads of their faith, just as we pull at the threads of history. Naftali recentres himself by praying three times a day, but his devotion is neither introspective nor arcane. The values he promotes within his organization – Aspiration, Authenticity, Balance, Care, Humility, Passion, Relevance, Responsibility, Trust and Unity – are universal.

Four of the first six surviving boys he found from the fiftyone – Yaakov Yosef Weiss, Chaim Schwimmer, Wolf Greenwald and David ‘Dugo’ Leitner – have passed away. Their legacy is a unique series of filmed interviews, detailing their experiences in Auschwitz-Birkenau, and their subsequent life lessons.

Their recollections are augmented by the eyewitness accounts of two more Hungarian Jewish boys who made it out alive, Avigdor Neumann and Yisroel Abelesz, and by the first-hand reflections of Yosef Zalman Kleinman, the youngest of 110 witnesses at the trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem in 1961.

Kleinman’s memories are acute, emotional without being overwrought. He embodied a survivor’s innate resilience during the Covid epidemic, when he posed for photographs in the narrow doorway of his apartment in Jerusalem, wearing a prison cap and a striped jacket with his Auschwitz number, 114968, above his heart.

In some instances, he held a photograph of his extended family, to symbolize the promise of the future. In others, he sought to address contemporary concerns with a note that read: ‘We will get through this.’ Naftali interviewed Kleinman in Israel in August 2020; he passed away, aged ninety-one, in May 2021.

Gathering testimony is not an exact science, since reminiscences are inevitably individualized. When old men tell their tales, recall can be selective, and beauty is invariably in the eye of the beholder. Yet there is a golden thread of authenticity to their reflections, which cannot be denied.

Yaakov Yosef Weiss, who was from Szilágysomlyó, which became known as Șimleu Silvaniei after it passed from Hungarian to Romanian control in 1944, was the first of the fifty-one to be tracked down by Naftali, at his home in Manchester two days before Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, in late September 2007.

‘Who are you?’ a gruff disembodied voice thundered across the intercom, in response to the ringing of his doorbell. ‘What do you want?’ Naftali, an honours student in the art of thinking fast on his feet, replied that his Rabbi had sent him to seek Weiss out ‘because anyone who has a number [an Auschwitz tattoo] and got out of that place with his faith has the power to bestow blessing’.

A tall, imposing figure emerged, framed by the doorway. Yaakov might have been intrigued by the younger man’s audacity, but it was not until July 2011 that he agreed to submit to a filmed interview. He had an agile brain and an encyclopaedic knowledge of the scriptures that aided philosophical debate, but he had little fondness for personal projection.

Weiss carried himself with a natural dignity, radiated an indomitable faith, and spoke with convincing clarity in measured, even tones, but it was his physical presence that left a lasting impression. He answered to the nickname of ‘Tarzan’ and had an unmistakable aura of authority.

A Rabbi, hugely respected in his community, he had a survivor’s self-sufficiency, and a painfully acquired perspective. ‘In the camp you see who has good character, and who is rotten,’ he reflected. ‘I have seen millionaires crawling for a piece of bread, and I’ve seen clever people being diminished to stupidities.’

He passed away, aged eighty-two, on 30 October 2013. It was not until November the following year, in the Jewish communities of New York, that two more of the fifty-one, Wolf Greenwald

and Chaim Schwimmer, were discovered, living four blocks from one another in the Borough Park district of Brooklyn.

Despite the profundity of their shared experience, the pair were not especially close. Wolf never attended the annual Seudat Hodoya, a so-called gratitude meal, hosted by Chaim at the Satmar Synagogue on 52nd Street for almost sixty years on the anniversary of their reprieve from the gas chamber. No slight was intended; Wolf’s life simply had different priorities.

Wolf had just celebrated his fourteenth birthday when he was transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau from Hajuduhadhaz, a town on Hungary’s Northern Great Plain. After liberation, he made it his life’s work to nurture future generations. He was revered for his commitment to his community, and spent fifty-five years as an administrator at a religious school in Borough Park.

Many of his twelve children became teachers, ensuring the family’s educational legacy. Like most of the fifty-one, he had been driven to honour the values instilled in him by his mother, from whom he was separated on their arrival in Auschwitz. He insisted: ‘The best way to teach is by example.’

‘My mother would have given the poor the clothes off her back. We were not a rich home, but she would spot a poor man, invite him in, and give him two slices of bread and butter. I never got the chance to say goodbye to her. So many people had their souls marched to the crematorium. It was such a lonely place.’

For Naftali, the dominoes began to fall when Chaim mentioned that his London-based cousin, Hershel Herskovic, was another of the fifty-one. Together with Hershel’s younger brother Yisroel, who escaped from the holding pen the night before their intended execution, they came from Munkacs, a commercial crossroads in the Transcarpathian region that typified the turbulence of the times.

The town was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire until the

end of the First World War, and was subsumed into Czechoslovakia in 1920. The Nazi annexation of the Sudetenland in 1938 led to fascist Hungarians seizing control of Munkacs until 1945, when, as Mukacevo, it became part of western Ukraine.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Jewish community was deep rooted and self-supportive. Until Yisroel made his break for freedom, leaping from the roof of their barracks before finding refuge with some Russian prisoners of war, the three boys had been inseparable in the camp. Chaim and Hershel entered the gas chamber together, determined to be as close in death as they were in life.

Hershel subsequently saved Chaim’s life on two occasions. Chaim would not have survived an initial death march, following the evacuation of Auschwitz-Birkenau in January 1945, without his cousin placing Chaim’s hands into the pockets of his own jacket, and dragging him behind him. Both knew that to stumble would be fatal.

Their ordeal was far from over when they reached Mauthausen concentration camp, where, in freezing temperatures, they lived in tents for two months from the start of February. Chaim was barely clinging to life following a second, gruelling, 60-kilometre march to Gunskirchen, on which around a quarter of the 20,000 prisoners died.

Hershel vividly remembers the pity in the eyes of their American liberators, who arrived in early May: ‘Chaim looked so ill. He could no longer walk, and his eyes were bulging. I was so exhausted I couldn’t think. They saw us and shook their heads. They obviously didn’t think there was any way we could live.’

Chaim takes up the story: ‘I got typhus and laid unconscious on the floor of an old hut in the woods for five days when we were liberated. My cousin thought I was about to die and begged the Americans to take me to hospital. They agreed, and nuns looked

after me. I was full of lice, which they brushed off with steel rods. After they washed me, I slept for two days. When I woke up, I was a new person. It was a kind of divine intervention.’

Following brief spells in France and England on an orphans’ relocation programme immediately after the war, Chaim moved to Montreal. The owner of a successful paper-products company, he spent twenty-nine years in Canada before settling in New York. He had five sons, fifty-three grandchildren and around 200 great-grandchildren when he died, aged ninety-four, in Brooklyn in May 2024.

Survivors tend to be complex, multidimensional characters, because they are products of a complex, multidimensional age. In emotional terms they are often like icebergs; a powerful presence with a hint of the unknown, since much lies beneath the surface.

Hershel is officially known by his mother’s family name, Herskovic, but in an interview for Steven Spielberg’s Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation, conducted in London in July 1997, he referred to himself as Solomon Taub, his father’s family name, which was taken by his younger brother Yisroel.

Such idiosyncrasy was common, in the shifting social, cultural and geopolitical climate in areas like Munkacs. Hershel’s parents were married in a religious ceremony, but their union was not officially recognized by the state, because of his father’s Galician origins. In such circumstances, families often used the mother’s family name.

It would also have been a prudent response to the plight of his father, who was in hiding at the time, because of the dangers of deportation to Poland. Yisroel felt able to take his father’s name, Taub, in the brief interlude of optimism in the early phase of the Second World War, when Munkacs moved from Czech to Hungarian control.

For the purposes of this book, we will continue to refer to him as Hershel Herskovic. The twists and turns of the project were borne out soon after I met him when, by chance, I read an article on the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, from October 2011, which led to the discovery that he was not the only living survivor among the fifty-one.

The ‘Seeking Kin’ column, by Hillell Kuttler, related the story of Mordechai Eldar, who was living in Herzliya, in the central coast area of Israel. He was looking for fellow beneficiaries of the Simchat Torah reprieve, and had made contact with one, Mordechai Linder, just before Linder’s death in the summer of 2011.

Eldar met up with another survivor, David ‘Dugo’ Leitner, but it was not until a follow-up article was published in 2016 that a breakthrough was made. Eldar received two emails in a week; the first was from Isaac Schwimmer, Chaim’s grandson, who also mentioned Wolf Greenwald, the grandfather of his wife’s brother-in-law.

The second was from Harry Ullman in London. He was a friend of Hershel Herskovic and had also known Yaakov Yosef Weiss. Chaim, Hershel and Wolf all admitted they did not know Eldar, and were unaware of his search, but his recollections, of what he arrestingly called an ‘exciting’ shared experience, because ‘exciting is the only word to describe it’, were clear and authentic.

Eldar, too, endured the second death march to Gunskirchen, where, weakened chronically by typhus, he was helped to a refugee camp by his American liberators. He returned briefly to his home town of Campulung La Tisa in Transylvania, where the only survivors of an extended family of fifty were his sisters, Ita and Sarah, and an aunt. He was reunited with his brother, Yehuda, in Germany in January 1946.

The four surviving siblings settled in the new state of Israel. Mordechai, a fervent Zionist, served in the Israel Defence Forces

(IDF) for thirty years, suffering a serious head wound in battle before retiring as a lieutenant general. He subsequently worked in construction and logistics management, and recently had his first great-grandchild.

When I passed on the two relevant articles inspired by his search to Naftali, he checked through his archives and found, to his great surprise, that he had forgotten a filmed interview he had conducted with Eldar in August 2023. It was a relatively simple task to confirm he was still alive, and playing a prominent role in Holocaust education.

His great friend Dugo Leitner, whom Naftali interviewed in Israel in August 2020, was a magnetic individual with a sharp sense of humour and a telling sense of optimism. He was established as a national treasure when he passed away, aged ninety-three, on Tisha Be’Av, the saddest day of the Jewish calendar, in July 2023.

The fondness towards Leitner owed much to his annual ritual of eating falafels on 18 January, the day he set off westwards on the death march from Auschwitz in early 1945. He ate them because they reminded him of the bilkelach, the golden-brown dough balls made by his mother, who was gassed within hours of the family’s arrival at the camp.

Such was the impact of Leitner’s simple act of homage that, by the time of his death, more than 100,000 people around the world, including Israel’s President Isaac Herzog, made a point of eating falafels on that day, in his and her honour.

Hope, he was fond of saying, is the greatest gift.

Josef Mengele, the Angel of Death, entered Block 11 in the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp on a cold, wet afternoon in October 1944. He had no need to be there, other than habitual devotion to the minutiae of his murderous task, and a perverted pride in his impact on those he had already condemned.

Eight hundred or so Hungarian boys were crammed into that bare, wooden barracks, which measured 116 by 36 feet. The bunks had been removed following an outbreak of scarlet fever that sent the previous occupants to the gas chambers. The boys were seized by a combination of sheer terror and morbid fascination.

They had not eaten for nearly two days. Many wept or prayed with desperate intensity; some appeared awestruck. In a place of brutally imposed servitude, everything about Mengele, from his haughty demeanour to his black leather overcoat, pristine white gloves and highly polished boots, was designed to intimidate and impress. His presence sucked the air out of the room.

David ‘Dugo’ Leitner, a fourteen-year-old boy from Nyíregyháza in north-eastern Hungary, thought of him as ‘spotless’, a handsome man with the aura of a film star. Yisroel Abelesz, another fourteen-year-old boy, from Kapuvar, a small Hungarian

town known for its thermal waters, was similarly mesmerized by the sharpness of his uniform, and the arrogance of his demeanour.

As Wolf Greenwald, who was approaching his sixteenth birthday, watched him instruct an underling to perform a headcount, he remembered stumbling off the cattle car at the railhead, and being ordered by an SS officer to take notice of Mengele’s fingers.

They moved from the knuckles upwards in a contemptuous flicking motion. The doomed were directed to the left; those reserved for hard labour before they were sent to meet their Maker were pushed to the right. The ritual was hypnotic, theatrical, dehumanizing and deadly.

Given quasi-scientific backing by the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Genetics and Eugenics in Berlin, Mengele used these selections to seek out raw material for his research into racial purity. Block 11, the first on the left after the entrance to the camp, had more recently been used as an infirmary but was his original laboratory.

A new numeration system was introduced in the latter half of 1944. Twins, girls aged from two to sixteen, and boys aged seven and eight, were placed in Block 1; their mothers remained in Block 22. Older boys, adult men, the disabled and dwarfs were imprisoned in Block 15.

Pairs of twins, dwarfs and others with ethnically defined or inherited medical conditions were initially examined and photographed. Their toeprints and fingerprints were taken, and plaster casts were made of their mouths, teeth and jaws. They were then killed, with phenol injections in the heart, so autopsies and analysis of internal organs could begin. Mengele personally administered deadly injections of phenol, petrol, chloroform or air.

Block 11 was now being used as a holding pen for those boys about to be taken to the crematoria. For the infamous doctor, who had returned from the Russian front with an Iron Cross and