ww w penguin .co.uk

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW

penguin.co.uk

First published in Great Britain in 2025 by Bantam an imprint of Transworld Publishers 001

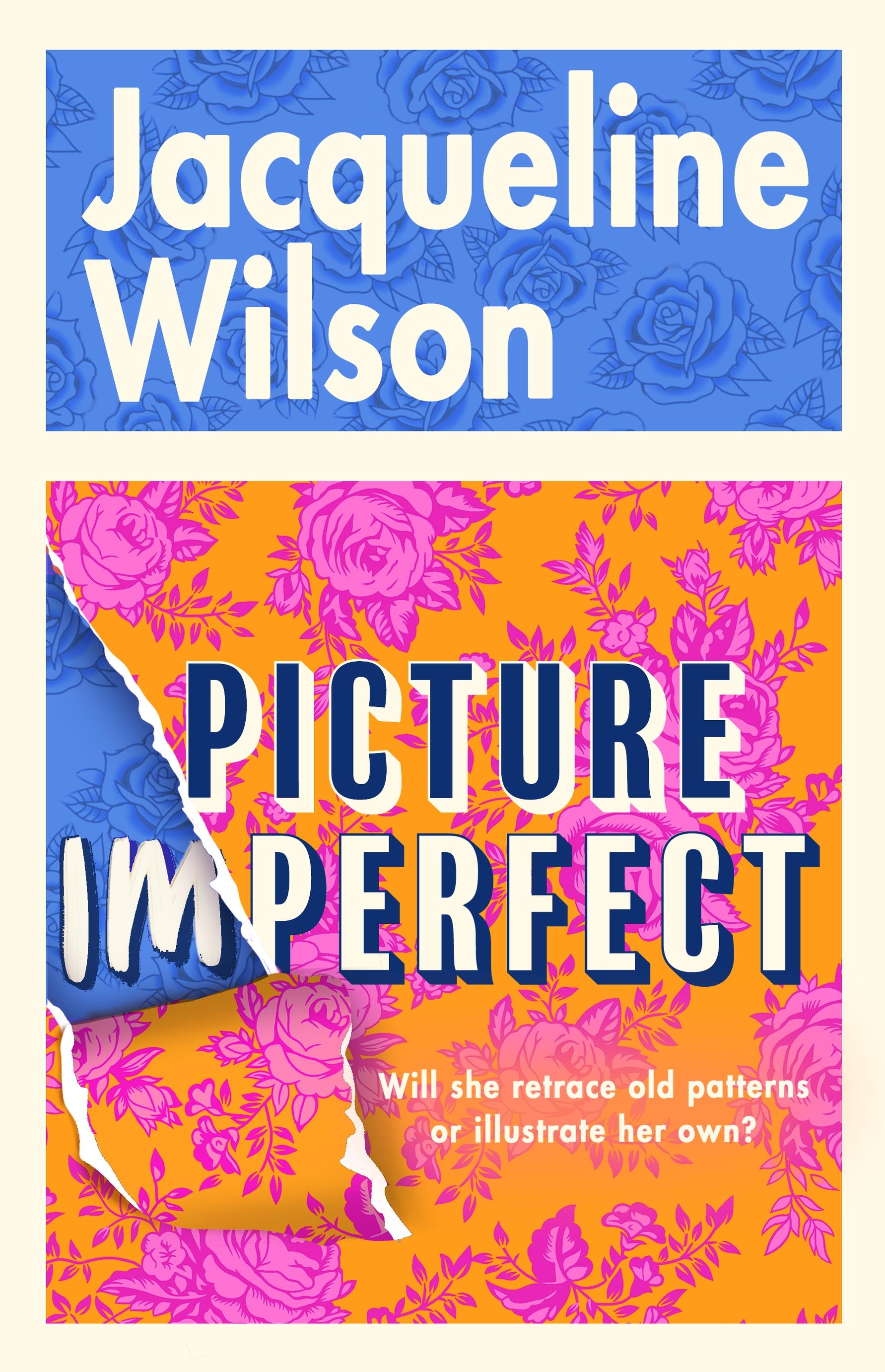

Copyright © Jacqueline Wilson 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

This book is a work of fiction and, except in the case of historical fact, any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset in 11.75/15.75 pt Sabon by Falcon Oast Graphic Art Ltd Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBNs:

9780857507631 (hb)

9780857507648 (tpb)

1I was designing a new custom piece, a dragon with gleaming green scales in a fiery tryst with a princess with red hair right down to her feet, when a jangling bell startled them apart. It took me a moment to realize I was dreaming – but the noise clamouring in my ears was all too real.

Feeling for my phone on the bedside table, I nearly sent it flying over the edge. Still bleary with sleep, I made a final, clumsy grab, and fumbled to press the green button. There was a voice in my ear.

‘Are you . . . Dolphin?’ a man asked uncertainly.

I started trembling. Very few people called me that now. Oh help, had Marigold created chaos again? I thought things were going so well.

‘Yes,’ I said, my voice husky.

‘Sorry to wake you up in the middle of the night, but we have a lady here who’s not very well and she’s given us your number. She says she’s called Marigold, Queen of the Sky?’ He pronounced it solemnly, but I could hear a colleague spluttering in the background. Perhaps they thought they’d stepped into a parody of Game of Thrones.

I breathed out slowly, sagging in despair. She’d come off her medication again. Why wouldn’t she ever learn?

‘My mother really is called Marigold,’ I said, trying to sound calm. ‘She suffers from chronic mental illness, as you’ve probably gathered. Where is she – in a nightclub?’

‘I’m a security officer at Gatwick Airport, North Terminal,’ he said.

‘What’s she doing there?’ I asked weakly.

‘She’s kicking up one hell of a fuss, that’s what she’s doing. She says she’s missed her flight. She’s had too much to drink, if you don’t mind my saying, but we get a lot of passengers like this. We were going to let her sleep it off, but she started screaming to get through to Airside because she wants to go shopping in Hamleys, even though we’ve told her they closed at eight p.m.’

‘I see,’ I said, my mouth so dry I could barely get the words out.

‘She’s still kicking off, lashing out, falling over. We’re concerned she might hurt herself more than anyone else. We’ve phoned a couple of hospitals but there aren’t any beds going spare on the psych wards. I suppose the police could collect her and pop her in a cell for being drunk and disorderly, but she seems a nice lady, shame to give her a criminal record.’

The ‘nice lady’ actually had a criminal record as long as her illustrated arm, but I wasn’t telling him that.

‘So what do you want me to do?’ I asked, though it was obvious.

‘Could you come and collect her?’ he asked. ‘You should see the state she’s in. And she is your mum, after all.’

She has another daughter! I’m her second daughter. Second by birth. And second best.

‘Of course,’ I said through a giant sigh. ‘It’ll take me quite a while to get to Gatwick, though.’

He’d already rung off. I stared at the glowing phone in the darkness and took in the time. Half past one! How in God’s name was I going to get to Gatwick? I didn’t have a car. I’d never even learnt to drive properly. A long-ago boyfriend tried giving me a

few lessons and kept losing his temper, saying I was so stupid I’d likely kill myself and any passengers the first time I took to the road. I wanted to run him over then. I imagined a tattoo of me driving a giant steam roller, turning him into Flat Stanley.

I didn’t persevere with our relationship or the driving lessons. So now I was stuck. There weren’t any trains at this time of night. I wasn’t even sure I’d be able to get a taxi – you mostly had to book a day or two ahead in Seahaven. I wouldn’t be able to afford it anyway. It was at least £70 to Gatwick, and probably another £70 back again, though if Marigold was in a state the driver would probably refuse to take her. I didn’t have £14 going spare, let alone £140.

Perhaps I could phone my dad to ask if he could possibly give me a lift? He’d helped me out with Marigold in the past. He’d always been kind to me, even though he didn’t know I existed until we met when I was ten. He’s tried to be in my life for the last twenty-odd years. Twenty-three years, to be exact.

I’m thirty-three, the same age as Marigold when she ended up in hospital for months. When she came out at last she seemed so different. We thought it was going to be all right. We’d be together again, Marigold and Star and me. But it didn’t work out that way. She had so many ups and downs that Star and I were in and out of care until we turned eighteen. Star seemed to do well in the system, relieved she didn’t have to look after me all the time. I never really coped, though. I just ached for Marigold. She meant all the world to me back then.

She still did now, in spite of everything. And I hated having to beg for help to sort her out, but there was no other way. I flipped through the contacts on my phone. Not that many. He’s under D for Dad, because it feels good remembering that I have a father like anyone else. I pressed ‘call’, though I felt sick now, worried about contacting him so late.

He’s always said, ‘Get in touch any time, Dol, I’ll always be there for you.’

I whispered this like a mantra as the phone rang and rang. Then suddenly there was a click and a voice. But not my dad’s. My heart sank at the sound of his wife, Meg.

‘Who is it? Is that you, Dolphin?’ she whispered, though she must have seen my name flash up on the screen.

She always pronounces it Dolpheen as if I’m a character in a country and western song. I once tried calling her Megaaan and she accused me of mocking her. Which I was, though I protested my innocence. She’s technically my stepmother but I’m pretty sure she can’t bear me. The feeling’s reciprocal.

‘Can I speak to Dad, please?’ I mumbled.

‘No, you can’t!’ she hissed.

I heard her moving around, a bed creaking, a door opening and shutting, and then the thump as she sat down on something hard. Oh God, was she in her bathroom? I really didn’t want to talk to Meg while she was on the toilet.

‘Do you have any idea what time it is?’

‘I’m so sorry to wake you,’ I replied, praying I wouldn’t hear her weeing. ‘But I need to speak to my dad.’

‘Well, as I said, you can’t! How could you disturb him in the middle of the night? You know he’s not been very well!’

There’d been something wrong with his heart rhythm, but he had a pacemaker fitted and he promised he was fine now. ‘The op wasn’t serious, Dol. I just needed to be rebooted, like a computer,’ he’d assured me.

‘I’m really sorry. I just wondered if he could possibly give me a lift to Gatwick,’ I said.

‘Gatwick?’ she exclaimed, as if I’d said Timbuktu.

‘Yes, I know, but Marigold’s been detained there and I have to collect her,’ I said, steeling myself for her reaction.

‘That effing woman!’ she said. She’s too genteel to come out with an honest ‘fuck’. What’s the matter with my parents? Why did they both choose horrible partners?

‘Dad said I must call on him to help out if she gets ill again. I promise you, he did say that,’ I gabbled.

‘Yes, well, he would, wouldn’t he, because he’s such a mug. Your mother’s nothing to do with him. He barely knew her.’

He lived with her for eleven months, and he loved her way more than he loves you. She was the one who left him and I’m not sure he ever got over it. So let me speak to him, you stupid bitch!

‘If I could just talk to him and explain—’ I started, but she’d already hung up.

I sighed despairingly. What was I going to do now? My head was thumping as well as my heart. I switched on the light and went to search the kitchen drawer. I haven’t actually got a kitchen, it’s a little recess in my bedsit containing a stove, a fridge and a three-drawer unit. If I had slightly longer arms, I could fry myself an egg sitting up in bed.

I found a packet of paracetamol and took a glass from the shelf. There was a sudden gushing sound before I turned on the tap. I stared at it in alarm – and then realized it was the tap the other side of the wall. The new guy, Lee, was obviously awake. Oh God, the Gatwick phone call probably woke him up too. The walls between our bedsits aren’t even like cardboard – more like opaque tissue paper.

I hoped he wouldn’t be too annoyed. He seemed a nice sort of man. I met him on the stairs last week when he moved in and helped him ease two dismantled beds round the bends. One was normal size, one was small.

‘Have you got a child?’ I’d asked hopefully. Unlike most renters, I love it if anyone has a small family. I’ve twice been an honorary Auntie Dolly, and I’ve babysat for free, played endless

games and invented stories for various small people. I’ve always got on with children. Star says it’s because I’ve never grown up properly myself.

‘I’ve got a little girl – my Ava. She’s the most amazing kid, four years old, perfect age, but I only get to see her occasionally,’ he said. He attempted a shrug, as if to say it’s no big deal, but he couldn’t stop his face crumpling.

‘Well, any time you need a babysitter, feel free to ask. I love kids,’ I said.

‘Thanks a lot,’ he said, looking really touched. ‘I take it you’re up in bedsit world because you’re on your own too. So if ever you need a hand, whatever, just let me know.’

He seemed lovely, though totally not my type: homely, fair curly hair, flushed cheeks, slightly tubby. The safe, teddy-bear type. Perhaps . . . the type to help out when you’re in a tough spot? He’s a gardener, so he had his van parked outside. Would he take me? But this wouldn’t just be lending me a hand. It was asking for two hands, two feet, to drive me all the way to Gatwick and back again with my sick mother on board. It was way too much to ask when I hardly knew him.

I was desperate, though. He was my only option. I pulled on jeans and a jumper, stuffed my feet into trainers, grabbed the key and shuffled into the corridor. I knocked tentatively and the door opened almost straight away. He looked like a giant little boy in his old-fashioned blue-and-white-striped pyjamas, his curls sticking up all over the place.

‘I’m so sorry, Lee – I think my phone must have woken you up,’ I said.

‘That’s OK, Dol,’ he said. I rarely told people my real name because it was so outlandish. ‘I hope it’s not an emergency?’

‘Well, it is, actually,’ I said, taking a deep breath. ‘My mum’s not very well. She’s stuck at Gatwick Airport and I have to collect

her. Um, you can’t think of any way I could get there, can you? There’s no public transport at this time and I haven’t got a car,’ I added, blushing at my sheer audacity.

I wouldn’t have blamed him if he shut the door in my face. But he was a kind man.

‘I’ll take you in the van,’ he said, smiling, as if it would somehow be a treat for him. ‘I’ll be ready in a tick,’ he said. ‘Hang on!’

‘You’re an angel,’ I declared, weak with relief.

I rushed back into my own flat, had a wee, cleaned my teeth, and grabbed my phone and credit card – could there possibly be a fee to pay for collecting a drunken mother? I looked for something to eat in the van to keep us going and could only find half a pack of Jaffa Cakes, probably stale, but they were better than nothing.

I heard Lee’s own front door opening and hurried back to mine. He was wearing jeans and a big scarlet sweater – a mistake with his ruddy cheeks, but he could have been wearing a sack for all I cared.

‘Your carriage awaits, ma’am,’ he proclaimed with a flamboyant gesture, as if he were a coachman and I was Cinderella. It was terribly cringy, but I smiled gratefully.

We went downstairs, tiptoeing in our trainers so as not to wake anyone else, and walked over to his minivan parked outside. I climbed into the front, sweet wrappers and crumpled fruit juice cartons crackling under my feet. I found myself sitting on a toy Alsatian.

‘Sorry, sorry,’ Lee said, bending to gather up the rubbish and shoving it all in a flowerpot at the back. He was gentler with the toy dog, placing him carefully on a sack of compost as if he was real, even giving him a quick pat.

‘That’s Fido,’ he said, when he caught me staring. ‘We got him from one of those arcade machines, Ava and me, and she insists I have him in the van to keep me company on journeys.’

‘That’s sweet of her,’ I said, putting on my seat belt.

‘Yes, she’s the sweetest kid in the world,’ he agreed. ‘Though I would say that, wouldn’t I?’ He started up the engine. ‘Right, Gatwick, here we come. Which terminal?’

‘North,’ I said. ‘Shall I look up the postcode on my phone?’

‘Don’t worry, I’ll find it. We go to Majorca every year – well, we used to . . .’ His voice tailed off sadly.

It sounded as if he and his wife had split up recently, but it seemed rude to ask. There was a little silence as we drove. It grew longer. Lee switched on the radio and some through-the-night pop blared out.

‘Sorry!’ he said, turning it down.

‘You don’t have to keep saying sorry to me! I’m the one who should be apologizing to you,’ I said. ‘You’re doing me such an enormous favour. You must at least let me give you some money for the petrol – though you might have to wait till I get paid.’

‘So what do you do for a living?’ he asked, sounding grateful for a topic of conversation.

‘I work in a place called Artful Ink. A tattoo studio,’ I told him.

‘Really? So you’re the receptionist?’

‘No, a tattooist actually,’ I said.

‘Seriously? I thought tattooists were hulking great men covered in ink,’ he said.

‘That’s the clients,’ I said, bristling. ‘Though they’ve changed nowadays as well. We often have professional people – and a lot of women too.’

‘Have you got tattoos, Dol? Show me! If – if it’s not in a difficult place,’ he said, suddenly embarrassed.

‘I haven’t got any at all,’ I said.

‘Oh well. I’m a gardener and yet I haven’t got a garden of my own at the moment,’ he said, sighing. ‘And to be honest, I don’t really think tattoos look that great on a woman.’

‘That’s a bit sexist, isn’t it?’ He was really starting to annoy me now, even though he was doing me such a good turn.

‘Sorry, sorry. I think delicate tattoos can look good on a woman – little daisies, bluebirds, that type of thing,’ he said quickly. ‘But you sometimes see women with tattoos all over, and that just looks, well, bizarre.’

‘Bizarre?’ I repeated.

He could tell by the tone of my voice that he’d said something deeply wrong. He glanced at me anxiously. I kept very still. If he said sorry one more time I’d start screaming.

‘I didn’t mean to offend you,’ he said quietly instead. ‘I should learn to keep my big mouth shut.’

‘I suppose I’m just a bit tense at the moment.’

‘Of course you are. You must be worried sick about your mum. I was just nattering on, trying to take your mind off things, and now I’ve ended up insulting your profession,’ he said.

‘Speaking of my mum,’ I said, taking a deep breath, ‘I think you’ll find her bizarre.’

‘What do you—? Oh God. Don’t tell me she’s got tattoos all over her?’ he asked.

‘She has. I didn’t do them, she’s had them since I was little. And added a lot more through the years. She’s got at least twentyfive – maybe more. All over.’

He took one hand off the steering wheel and smacked the side of his head. ‘I’m an idiot. How could I have been so flipping tactless?’

I sighed. He could be Meg’s soulmate, with that weak substitute for ‘fuck’. Then I felt terrible. I had to stop this. I have a habit of being antagonistic to kind people because they fluster me. Star says that’s why I’ve always had such rubbish relationships. It’s because I deliberately go for bad boys who will let me down. It’s as if I’m outwitting my own gullibility. If I choose an

obvious bastard then I won’t break my heart. I know exactly what to expect.

Well, that’s what she says. Anyone would think she was a psychiatrist instead of a GP. My sister, the doctor. I still can’t get my head around it.

‘You weren’t to know. And actually, I think she looks bizarre, though I thought she was beautiful when I was a kid,’ I said.

He murmured sympathetically, not risking saying anything else at all.

‘She has bipolar disorder. She always gets another tattoo when she’s in a manic phase,’ I said. ‘She’s obviously in one now. I just hope she’s not got an eagle flying across her forehead or a spider on both cheeks.’

He grunted, sounding appalled, but stayed heroically silent.

‘I’m joking. Though the joke will be on me if she’s done just that,’ I said. ‘You must think I’m dreadful, joking about my own mother. I know she can’t help it, she’s mentally ill. I’m just so sick of having to deal with it.’ My voice wobbled dangerously.

‘It must be an awful strain,’ he said quietly.

His genuine sympathy was too much, and I turned to look out of the window so he couldn’t see the tears spilling down my cheeks. I didn’t see how I could keep on coping – but what choice did I have?

2I felt totally unnerved when we’d parked the car at the airport. I’d only been abroad twice in my life and found it all entirely confusing. Lee steered me around and found the right place near Passport Control.

‘Ah, you must be Dolphin,’ the security man said, though he looked uncertain. Perhaps he’d been expecting someone as colourful as Marigold, not a little mouse in a jersey and jeans.

‘Dolphin?’ Lee muttered, staring at me. I gave him a rueful shrug.

‘Are you her partner?’ the security man asked Lee, looking relieved. Perhaps he thought I’d start kicking off too. Lee looked the sort of capable man, strong but kind, who could cope with hysterical women.

Lee shook the man’s hand firmly.

‘I’m a family friend,’ he said.

‘Well, come this way, both of you.’ He beckoned us forward.

I’d imagined Marigold screaming in a cell but she was sitting at a table in an ordinary office. Another security man was with her, drinking a mug of tea. Marigold had a mug too, clasping it with both hands. She was shaking, and some of the tea had splashed down her white lacy top. It was very skimpy, displaying too much tattooed chest. Her skirt was very short too, though

her long, bare legs were still shapely. She’d kicked off one high heel, revealing the green frog tattoo peeping out between her toes.

Her head was bent, her red hair hiding her face. I could see her white roots.

‘Marigold!’ I ran to her, took the mug from her and wrapped my arms tightly round her.

I breathed in her familiar smell of perfume and sweat and alcohol. When I was a little girl I’d snuggle against her and she’d hold me close, her long nails lightly tapping out a tune on my back. I was the one holding her close now.

‘There now, Marigold. I’m here now. We’ll get you home, don’t you worry.’

She stiffened and pulled away from me. ‘I don’t want to go home! I’m getting the first plane to Scotland in the morning! I’ve got to see my grandchild!’

I froze. How in hell had she found out about Star’s child? I’d solemnly sworn to Star that I’d keep it a secret. I hadn’t breathed a word to anyone – oh God, except Steve.

I’d bumped into him at the tattoo fair at Olympia. Marigold used to work for him long ago, and though he looked like the tough, inked-all-over tattooist of Lee’s imagination, he was like a jolly uncle to Star and me. I’d done my initial training with him. He’d always been sympathetic about Marigold, but that day he kept shaking his head and making tutting noises. I found myself boasting about Star to show that the family had one success story.

‘Star’s still up in Scotland. She’s a fully qualified doctor now, would you believe? She’s married to another doctor and they’ve just had a baby boy. I bet they’ve strung a tiny stethoscope round his neck for him to teethe on!’

I’d felt anxious as soon as the words were out of my mouth. Star had been so insistent that Marigold mustn’t know – but I’d reasoned that the chances of Marigold herself bumping into Steve

were minimal. She couldn’t do any inking herself now because her hands shook too badly, and she knew Steve wouldn’t touch her skin since she’d picked at a newly inked butterfly on her calf and it had turned septic. But clearly, I’d been wrong.

‘Why didn’t you tell me, Dol?’ Marigold wailed, and started beating me on my shoulders, arms, chest.

She wasn’t really hurting me, she was just hitting out feebly in frustration, but the security guard cried out, ‘Hey, stop that!’ and Lee grabbed Marigold’s wrists, holding them firmly.

‘Ah! Ah!’ he said, like Graeme Hall taming a boisterous dog. ‘Calm down, now! You don’t want to hurt your daughter, she’s trying to help you!’

Marigold tried beating at him too, but then collapsed against him, sobbing. Lee held her, patting her back, as if comforting a sadly befuddled woman in the middle of the night was an everyday occurrence. The security guards exchanged glances.

‘That’s it, mate. She obviously thinks a lot of you,’ he said, as Marigold clung to Lee. ‘So do you think you can take her home now?’

‘Of course I can,’ said Lee, kindly not telling them that he’d only met Marigold that minute. ‘Come on now, Marigold, let’s thank these guys for looking after you, and then we’ll take you back home, OK?’

She looked up at him, grateful now, but still highly agitated.

‘You’ll bring me back, though? I have to see the baby! He’s Micky’s grandchild!’ she garbled.

‘When you’re a bit better,’ Lee said. ‘Come on now! No need to cry!’

She was gasping now, choking on sobs, her eyes wet, her nose running, but he still hung on to her valiantly. I started sweating with embarrassment as we bundled Marigold away with us. A few stray travellers spread out on the seats gawped at us as if we

were a freak show, but Lee ignored them and I tried to follow his lead. It was an enormous relief when we got back to his van.

‘In you hop, Marigold,’ Lee said.

Marigold pushed her tousled hair out of her eyes and peered at the van suspiciously.

‘I’m not going in that!’ she protested.

‘Oh, for God’s sake, Marigold!’ I said, trying to get her to climb in the back.

‘Not fucking likely!’ Marigold yelled in the echoing car park, never a woman to bother with substitutes. She called Lee worse names as he tried to lever her in too.

‘He’s going to bung me back in hospital, isn’t he!’ she screamed. ‘You can’t fool me! You’re egging him on, because you just want to be rid of me, Dol! I want Star! I want Star and her baby and my Micky!’ I felt like shaking her, though I knew she couldn’t help it.

‘He’s not taking you to hospital, I swear it. He’s my neighbour and he’s being kind enough to help us. He has a van because he’s a gardener. We’re going to sit in the back and you’re going to stop shouting and swearing and shut up!’ I said fiercely.

It was the wrong tone, the wrong words, way too brutal – but it worked. Marigold and I sat in the back together, and I held her, and she stopped fighting me and subsided with her head on a sack of compost beside the toy dog.

‘Are you all right back there?’ Lee murmured.

‘Yes, fine,’ I said, though of course it was anything but. I was trying to make up my mind what on earth I should do. Could I ask Lee to take us all the way to Marigold’s flat, which was miles past our own? And if he did, there was likely to be another fracas. Marigold’s partner Rick particularly disliked me. His way of greeting me was always, ‘Watch out! Here comes the killjoy!’ His definition of joy was encouraging Marigold to spend her benefits on drink and dope, and suggesting she come off her Lithium

because he said she was ‘more fun’ without it. No wonder I was a killjoy. I often felt like killing Rick myself.

The only other place she could go was back with me, and that made me feel sick with dread. I loved Marigold, I truly cared about her, but she was such hard work. Was I going to be stuck doing it for ever? I’d lost jobs before, because I hadn’t been able to risk leaving her when she was in a psychotic phase. I’d lost flats. I’d lost friends. I’d lost my own life. It was so fucking unfair. Why wouldn’t Star ever take a turn?

‘Dol?’ Lee must have seen me in his rear-view mirror.

‘I’m OK,’ I insisted.

‘You poor thing,’ he said softly.

Why couldn’t I fall in love with someone like him, who’d always help me and try to understand?

Marigold moaned sleepily, half lifting her head.

‘Shh now! Try to go to sleep,’ I said, patting her back. I could feel her shoulder blades, sharp as little axes. She was obviously not eating properly. Not doing anything properly.

She wriggled, her hand going to her chest. Oh God, was she going to be sick? She’d certainly drunk enough. It would be the final horror if she was sick in Lee’s van, and I’d have to mop it all up and scrub the floor.

‘Hang on, Marigold,’ I whispered sternly.

Thank God she did manage it, though the moment we got her out of the van she threw up. At least she did it neatly in the gutter while I held her head and kept her hair out of the way. Lee tactfully turned his back on us, but as soon as she’d finished he took her arm to help her along.

‘I take it she’s staying the night with you?’ he asked.

‘I suppose so,’ I said.

‘I’ll be right next door if you need me for anything,’ he reassured me.

‘You’re an absolute angel,’ I said.

‘Hardly,’ he said, grinning. ‘I wouldn’t do this for anyone else, you know.’

What did he mean? Did he mean I was special? Did he fancy me? It didn’t seem likely. I’d got very thin, my hair badly needed cutting into some sort of shape, and I was as pale as a ghost because I didn’t bother with make-up any more.

I smiled at him uncertainly as he got the front door open, then we took Marigold’s arms and helped her up the three flights of narrow stairs. The effort left us all panting. He helped me get her in my own front door and then looked round, momentarily distracted.

‘Your room’s so different!’ he said.

Our bedsits were identical in shape and size, but I had made mine into the fairy grotto of my childhood dreams, with twinkly lights, miniature gardens in glass bottles and dolls sitting on the window sills. I’d covered the shabby furniture with embroidered throws, papered the cracked walls with pictures and posters and cards, and installed a vintage mannequin from a closing-down dress shop for company, buying her a long blonde wig and making her a Biba-type velvet dress so she’d feel glamorous.

I loved the way it looked, but, seeing it through Lee’s eyes now, I was painfully conscious that it was a little girl’s fantasy room, not a sensible home for a thirty-three-year-old woman. I felt my cheeks flush.

‘It’s all a bit childish,’ I mumbled.

‘I think it’s amazing,’ Lee breathed.

‘That’s my Dolly for you,’ Marigold said, her voice slurring. ‘Creative. You take after me, don’t you, darling?’

I couldn’t think of anything worse than taking after Marigold, but I knew she meant well, and I was so relieved she seemed to have stopped being angry with me.

‘Come on then, Mum, let’s get you to bed,’ I said. I felt selfconscious calling her ‘Mum’, but I liked to do it when I felt really fond of her.

‘My girl!’ said Marigold, and gave me a clumsy hug. The lingering smell of sick made my nose wrinkle, but I didn’t pull away.

‘Well, I’ll leave you two to catch up on your sleep,’ said Lee. He looked at me, then back at her. ‘Do knock again if you need me.’

‘Thank you so much for everything. You’ve been a total . . .’ I couldn’t keep calling him an angel. ‘A knight in shining armour,’ I said instead, imagining him in medieval polished steel, with a purple plume flowing from his silver helmet. It was a popular tattoo for besotted young girls newly in love. The image suited Lee tonight, despite his homely face and sturdy body.

He grinned at me, nodded to Marigold, and left us to it.

‘Are you two fucking?’ Marigold asked before he’d properly shut the door.

‘Shut up! No, we’re not!’ I hissed, fetching her a clean nightie.

‘Why not? Is he a bit too dull? Mr Nicey Nicey?’

‘That’s a terrible thing to say, when he’s been so kind,’ I said, pulling her top off. I could see every rib. Her breasts were tiny puckers now – the python lasciviously coiling round them was going to have a very meagre meal. I pulled the nightdress over her head hurriedly, poking her arms through the sleeves. Then I hung on to one arm, horrified. Were these marks needle tracks?

‘Oh my God, are you injecting now?’

‘I’m not a fool,’ she protested. ‘Rick and I might smoke a little weed sometimes, but you know I’m squeamish with needles.’

‘So how did you get these marks?’

‘I don’t know,’ she said, shrugging.

‘Look, this one’s oozing! It’s all infected. You should see a doctor!’

‘Well, you can’t get to see one for months nowadays so what’s

the point in trying? Oh, wait! I’ll ask Star when I see her tomorrow!’ she said, glowing at the idea.

‘Don’t start that again,’ I said, trying to bundle her into bed.

‘I’m going! First thing tomorrow!’ she declared, struggling with me. ‘Lee can drive me straight back to the airport!’

‘Lee will be going to work, and so will I. And I don’t know what you’ll be doing, but it’s certainly not going to Scotland. You haven’t even got a ticket for a flight, have you?’

‘I’m buying one. I’ve got a credit card, see,’ she said, opening her bag, the stitching unravelling, the lining torn. She pulled out vapes, eyeliner, lipstick, a little brush with several missing bristles and, finally, a worn wallet.

‘See!’ she said, brandishing it.

I grabbed it from her and opened it. It contained a long-ago crumpled photo of Micky with his arm round Star, another photo of Star and me as little kids dressing up in Marigold’s clothes, a voucher for a free cup of coffee and an old cinema ticket. It also had a credit card, but when I looked at it carefully it was months out of date and had someone else’s name on it anyway.

‘That’s not going to buy you a ticket to Scotland, is it?’ I said.

‘It might,’ she said. ‘Or – or someone else might have dropped one by the ticket machine.’

‘Oh, for Christ’s sake, Marigold, stop playing silly games. You can’t really be that stupid.’

‘Then you lend me the money, Dol. Please! I have to go and see my grandson! That’s not crazy, is it? Every grandma on earth wants to see her grandchild. Why didn’t you tell me about him? How can you be so cruel?’ she said, kicking at me feebly as I tried to haul her legs into bed.

‘I haven’t even seen him. Star never wants to come and see us.’ I chose not to mention that Star had often invited me up to Scotland, though.

‘She’s my daughter! Micky’s child!’ Marigold shouted. ‘My Micky – the love of my life.’

How often had I heard that? She meant it too, even when she was sober and sensible. But they’d parted so long ago I wasn’t even sure she’d recognize him now if he walked straight past her. A fantasy Micky glowed in glorious Technicolor in her mind. Sometimes I wondered if she’d even know the glossy, grown-up Star in the photos she sent me.

If only she were here too, helping me cope.

‘Star! Star, Star, Star!’ Marigold called, as if summoning her.

‘Shh! We’ve disturbed Lee enough for one night. And stop going on about Star. I miss her just as much as you do. She’s my sister!’

She wasn’t just a sister to me. She’d been like my mum when I was little, looking after me valiantly when Marigold was having an episode. She’d been my best friend too. No matter how scary life got, Star was always there for me. Well, most of the time. I was terrified when she went to live with Micky, thinking I’d lost her for ever, but thank God that didn’t last long.

She came back and coped with Marigold, and I relied on her utterly. I found it very difficult when she went away to university. It was a shock when she chose to read medicine at St Andrews, almost as far away as she could go. She made one fleeting visit home the first Christmas, and after a few months Marigold managed somehow to raise the money for the two of us to make the complicated journey up there.

The visit wasn’t a success. Marigold and I were both overwhelmed by the university, the entire town of St Andrews, Star’s new boyfriend Charles and, most of all, Star herself. She didn’t seem part of our family any more. She’d grown her hair longer, removed her nose stud, and wore soft, ladylike sweaters, smart jeans and bright white plimsolls. She didn’t even sound like

herself. Rather than picking up the soft Scottish lilt, she spoke posh English like most of the other students up there.

I felt uncomfortably in awe of her and became practically monosyllabic, unable to confide all the things I’d been bursting to tell her. Marigold went the other way, talking too loudly, wearing her brightest lipstick, her shortest skirt, her highest heels. She even called Star’s posh boyfriend ‘Charlie Boy’. He was smoothly polite, but he couldn’t look at her without fractionally raising his eyebrows. She was so different from all the other visiting mothers – a squawking parrot in among a flight of doves.

I looked at Marigold now, so pitiful and bedraggled, her garish make-up smeared. I felt bad about not washing her face, but it was struggle enough to get her into bed. The moment I got her lying down she reared up again, words tumbling out of her smudged mouth in an incoherent babble. I’d been planning to sleep on the sofa, but the only way I could manage things was by wriggling out of my clothes and getting into bed beside her.

She still fought me, as if I was intruding in her bed, but I held her tight and felt her slowly relax. How long had she been awake? In a manic phase she often didn’t sleep for days, and her voice got even higher until it sounded as if she’d been inhaling helium. She was still slurring too, drunker than I’d thought. Maybe she really had had money for a ticket but had bought herself too many double vodkas to give her the courage to go? I felt a pang of sorrow for her.

She’d started to shake again. I patted her and murmured all the soothing words I could think of. I even sang to her the way she’d crooned to me when I was little: Hush little baby, don’t you cry, Mama’s going to sing you a lullaby.

I sang it until her eyes closed and my own voice started slurring, and I fell asleep myself.

When I woke the next morning, I reached out for Marigold but just felt crumpled sheets. I swept my hand up and down, feeling with my feet too, as if she might be curled up at the bottom of my bed like a cat. I sat up and peered round the room. She wasn’t anywhere.

I hurried to the little ensuite – a rather grand word for the toilet, basin and shower crammed together in their cupboard –but Marigold wasn’t there. She wasn’t in the corner kitchenette either. She wasn’t anywhere.

Had she gone to find Lee? I pressed my ear against the communal wall but I couldn’t hear any voices. I looked back to the bed where Marigold’s clothes had been scattered. They were gone, even her high-heeled shoes.

I glanced at the clock. Half seven. Had she crept back to her own flat, and horrible Rick? I tried ringing her but a recorded voice told me no one could take my call right now. I knew it simply meant Marigold had switched her phone off, but it still sounded ominous. I was always so scared that Marigold might kill herself when she tipped from very high to very low. She’d already tried twice, once slashing her wrists, another time dashing in front of a car. What if last night drove her to try again?

I struggled into yesterday’s clothes, had the quickest pee while

pulling on my shoes, and then rushed from the flat without even cleaning my teeth or brushing my hair. I hesitated in the street, not knowing which way to run. Should I make for the cliffs? But there was no way Marigold would hurl herself into the sea. She was terrified of water. My swimming-coach father had never succeeded in coaxing her into even the shallow end of his leisure centre pool.

I ran the opposite way, towards the station. She’d once made a friend of a woman in her psychiatric wing who had set off at a run when the ward was unlocked. She made it out the hospital, ran half a mile in her medical gown and hurled herself off a railway bridge when the eight o’clock London train was rumbling underneath. I’d been horrified, but Marigold had seemed unmoved, remarking that at least it had been a quick death by all accounts. At the time I was shocked by her lack of empathy. Now I wondered if she was filing it away for future reference.

I couldn’t think of any nearby bridges, but there were halfhourly trains from the station that quickly gathered speed along the track. My thoughts were gathering speed too, seeing Marigold running in her high heels, staggering up a grassy bank near the station, and then crouching, ready to leap.

I sped along, my heart pounding, a vile metallic taste in my mouth, not caring that people on their way to work were staring at me.

Then I saw her, standing at the top of the station steps, singing. A bemused crowd watched or edged past hurriedly. My mother, with her make-up still smeared, though she’d reapplied scarlet lipstick going way over the line of her mouth. She was wearing last night’s clothes and those wretched high heels, and a hat lay on the ground in front of her. With a jolt, I realized it was my sunhat, upside down, clearly there to catch coins – although none were being proffered.

The song she was singing had a thumping rhythm and she was stamping her feet energetically. It was dimly familiar, an old Proclaimers song, something about walking five hundred miles, though she kept adding an extra riff: to see my grandchild!

For a split second I felt the urge to pretend I hadn’t seen or heard her. I could scurry past and go about my ordinary life and not give her a second thought – like Star.

But I couldn’t do it. I dashed up the steps towards her, pushing through the gathering crowd. Marigold gave a start when she saw me but kept on singing determinedly.

‘Marigold. Stop it.’

‘Just keep out of it. As you’ve taken my plane ticket and all my money I’m going to sing and sing until I’ve got enough to go by train, so there!’ she said, still stamping her feet.

‘I didn’t take your ticket, I didn’t take your money, you know I didn’t. And this is all pointless, because even if you did get there, you don’t know Star’s address. You can walk your five hundred miles all over Scotland but you haven’t got a clue where she lives,’ I said steadily. ‘Now come back with me.’

I tried to take Marigold’s arm but she pulled away from me violently.

‘Of course I know where my own daughter lives,’ Marigold said furiously. ‘You get the train to London, and then another train, and then another train, anothertrainanothertrainanother . . . heaps of trains to this little Saint place, I can’t remember which, too many saints, oh dear God those nuns and their Saint Annes and Saint Michaels and Saint Jude the patron saint of lost causes and I suppose that’s me, lost cause.’

She often talked about her childhood, the fierce nuns who ran the children’s home, who rapped her on the head with their hard knuckles and slapped her whenever she wet the bed, as if it were the reason for her bad behaviour in adulthood.

Well, Star and I had had our fair share of taps and slaps from Marigold herself – though she had loved us too. I remembered all the games she played with me, the cakes she baked, the dances she taught us. I hero-worshipped her when I was little. It was so awful to see her now, manic, hungover, dishevelled, totally pitiful.

‘Oh, Marigold,’ I said softly, coming closer. ‘I’m so sorry but—’

‘Don’t you dare feel sorry for me!’ she hissed, so that several drops of spittle landed on my cheek. ‘I’m not listening. I know how to get to Star, Star Light, Star Bright—’

‘Stop it, Marigold! You’re talking gibberish because you’ve come off your meds. And you don’t know how to find Star – she left St Andrews years ago when she got her degree. It’s true. I don’t lie to you, do I?’

That was a lie in itself, though I wasn’t lying about this. Star had lived in several different places as she and Charles climbed steadily up their medical ladders. He was already a consultant at the Dundee Royal Infirmary and Star worked in a big medical practice as their women’s health expert. They lived in a four-bedroom house in the West End of Dundee. Four bedrooms! They obviously earned good money, and Charles’s family were generous.

I’d never been there. Star had invited me several times, especially for Christmas, but I’d always made excuses. I didn’t want to be Star’s weird wee sister the tattooist, the odd one out among her genteel middle-class Scottish friends. The one who took after the unfortunate mother.

Perhaps I was just being paranoid. But that would mean I was taking after my mother. She was staring at me, shaking her head violently, though I could see from her eyes that she’d taken in what I was saying.

‘I know an even better way to get to Star!’ she declared, her chin up. ‘I shan’t bother with trains and planes. I’ll fly there myself!’

Before I could take in what she was saying, she took a sudden huge leap. She spread her arms, her legs kicking, as if she were a cartoon character dangling in mid-air, but then she went crashing down the steps, her handbag bumping down behind her. She landed on her face, arms still outstretched, one foot sticking out sideways at a grotesque angle.

I hurtled down the steps, elbowing people out the way. Someone got to her first but I shouted, ‘Let me! She’s my mother!’

I crouched down by her side. I knew I shouldn’t try to move her, I could see her ankle was broken, and her head was at a funny angle – oh God, don’t let her neck be broken too! I was trembling so much I couldn’t control my hand, but I managed to push her hair away from her face. Her eyes were half closed and there was blood coming from her nose, but I could see her lips moving.

‘Oh, Marigold, it’s all right,’ I mumbled helplessly. ‘I’m here. Your Dol’s here. And we’ll get you better, and I’ll look after you, I promise I will.’

People around me were on their phones, calling an ambulance, and someone in station uniform was squatting down beside us, babbling something about a first aid course, trying to move her.

‘Leave her alone!’ I snapped, bending right over her like a lioness with her cub, trying to protect her from their touch, their gaze. I stroked her hair very gently, then bent even closer so I could sing the ‘Hush Little Baby’ song right into her ear. Her eyes fluttered and for one moment she looked straight at me, and I could see she knew I was there.

The wait could have been ten minutes or ten hours. We seemed suspended in time. The steps emptied because the station employee wasn’t letting anyone else go past. I heard trains

rumbling in and out of the station, and I thought about all the passengers. Were they having to miss their trains because of us?

Marigold’s eyes were closed now, but I could feel her breath on my hand so I knew she was still alive. Perhaps she was flying in her head, out of the station, above the roofs, right up into the cloudy sky, all the way to Scotland. I hung on to her as hard as I could.

Someone patted me on the shoulder, trying to comfort me, and someone else asked if I’d like a cup of tea, which seemed a bizarre suggestion at such a moment, but I suppose they were simply trying to be kind. Then the paramedics arrived, and bent down beside Marigold, testing her methodically, murmuring to each other. I stood back to let them work, my eyes fixed on Marigold’s face all the while.

It was a tricky job getting her on a stretcher and she groaned a lot. I tried to hang on to her hand to show her I was still there, and we went out of the station in an awkward procession. One of Marigold’s heels fell off and I stopped to pick it up, and her bag too. It felt as if I was gathering up actual parts of her – a foot, a hand.

Then we were in the ambulance, and I was shaking so badly I couldn’t speak properly. The woman monitoring Marigold was very patient and listened to my stutters carefully.

‘She’s bipolar, she’s not been taking her Lithium, she thought she could fly, or maybe she was trying to kill herself, I don’t know! She ran off while I was asleep, I had to rescue her from Gatwick in the night. I don’t know how to keep her safe.’

‘It sounds as if you’ve done your very best. They’ll look after her in hospital. She’s obviously hurt herself, and that ankle’s definitely broken and she’s smashed her nose, but let’s hope she’s not done any serious damage. They’ll patch her up and put her on her meds and see if they can sort her out mentally as well as

physically,’ the woman said reassuringly. I wanted to cling to her like a little girl and beg her to keep saying it again and again.

She didn’t once reproach me for not stopping Marigold, and I loved her for it. I was feeling desperately guilty. I kept replaying the whole scene – Marigold stamping her feet at the top of the steps, then suddenly leaping into thin air. Could I have caught her? Grabbed hold of her the moment I saw her? And why in God’s name didn’t I wake up when she crept out of bed?

Then we were at the hospital. I thought she’d be whisked out and dealt with straight away because this was definitely an emergency – but of course, we had to wait ages in a queue of ambulances, and then longer still to get her assessed in A&E, and by the time all her injuries had been checked and she’d been X-rayed, her broken ankle temporarily strapped into place and she’d been wheeled off to the psychiatric ward, it was late afternoon.

It was painted pale yellow, called Primrose Ward. It was kept locked, with a firm notice on the door that visiting hours were ‘2 to 4 ONLY’ – but I tagged along with the porter and managed to talk the attending nurse into letting me stay to help calm my mother down. Marigold was beside herself by now, shouting and swearing, so the nurse readily agreed.

It was terrifying seeing her so wildly out of control, with her face smashed up. She’d been so pretty when she was younger. I remembered wishing hard that I could grow up to be just like her – yet now the thought frightened me.

‘Can’t you at least give her a proper painkiller?’ I begged the nurse.

‘I need to check with Dr Gibbon first,’ she said.

Dr Gibbon? I was in such a state I pictured him swinging along the ward by the light fittings, long, hairy arms sticking out of his white doctor’s coat, a stethoscope round his neck.

I’d always imagined weird stuff when I was a child and fell back into the habit when I was feeling intimidated. I was frightened of hectoring doctors, though Star always told me not to be such a fool.

But Dr Gibbon turned out to be a spindly youngish man with a lot of golden-brown hair and a friendly grin – more spider monkey than gibbon. Rather than the usual white coat he wore a crumpled blue shirt, baggy trousers and battered trainers.

‘Hello. Are you my new patient’s daughter? Tell you what –you pop into my office and wait while I examine your mum and try to make her more comfortable. Then I’ll come and find you and we’ll have a chat. OK?’

I felt the tightness in my chest loosen a little. I heard Marigold swearing at him from far away at the end of the ward, but gradually she seemed to calm down. I sat biting my nails, peering round the small room. I expected the walls to be plastered with medical charts and those weird drawings of heads coloured in different segments – but he had travel posters and photos of his wife and two small children sellotaped there instead.

I stared at his family until my eyes blurred, glad that they all seemed so smiley and ordinary. The sort of family I’d always longed to be part of.

Dr Gibbon actually knocked at his own office door before he came in.

‘How are you coping?’ he asked gently, as if he really cared.

I shrugged, so touched that I nearly burst into tears.

‘I should imagine this scenario is relatively familiar?’ he asked.

‘Yes,’ I said, sniffing.

‘Your mum told me she’s been locked up in effing hospitals half her life and she’s effing fed up with it and she doesn’t want to talk to an effing idiot like me. And I don’t actually effing blame her.’