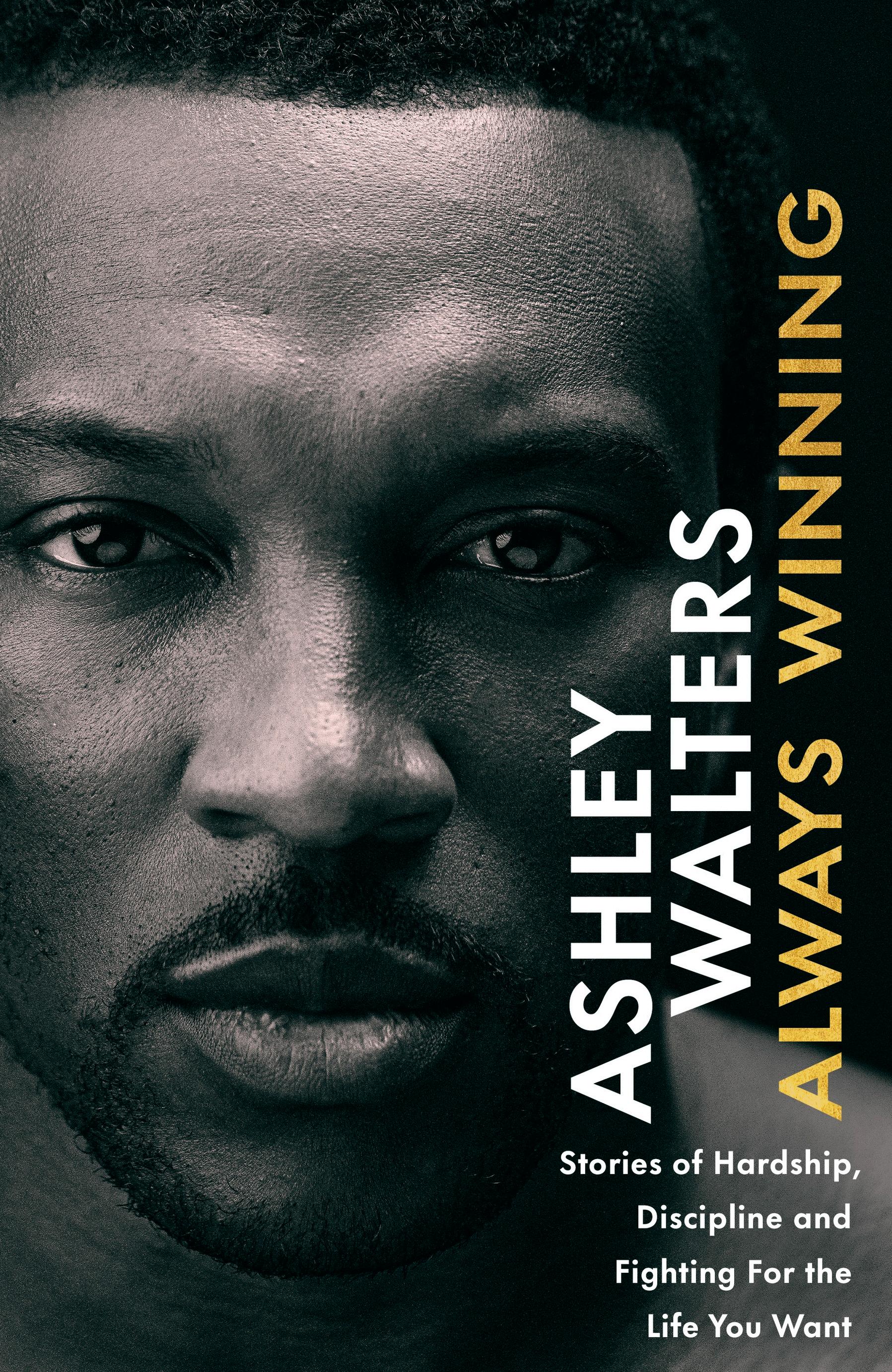

Stories of Hardship, Discipline and Fighting for the Life You Want

Hardship, Discipline and Fighting For the Life You Want

WITH CHRIS ISAIE

WINNING

TRANSWORLD PUBLISHERS

Penguin Random House, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW www.penguin.co.uk

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published in Great Britain in 2025 by Bantam an imprint of Transworld Publishers

Copyright © Ashley Walters 2025

Ashley Walters has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBNs

9780857506429 (cased)

9780857509093 (tpb)

Text design by Couper Street Type Co.

Typeset in 12/18 pt Sabon by Falcon Oast Graphic Art Ltd Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68.

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

This book is dedicated to the pillars of my life.

To my mum – your love taught me resilience and gave me my strength.

To my wife – your belief and support have not only driven me further but inspired me to dream even bigger.

To my kids – you are my heart, my drive and my ultimate purpose. Each day you remind me to aim higher and do better.

A NOTE TO THE READER

If you take nothing else from this book, take this: no matter where you’re from, no matter what you’ve faced, success is yours if you believe in yourself and refuse to quit. I’ve done it. You can too.

With gratitude, love and hope for your future.

Ashley Walters

A SCREAM. THEN A STRUGGLE. FOUR HARD BLOWS TO THE chest, the final one causing him to cry out. He slumps back against the wall, slides down it. The sound of tyres screeching, then silence. The boy holds his hands to his stomach, panting. I can see the whites of his eyes, wide with fear and pain. Blood pools on the concrete.

‘That’s it.’ The sound of people letting their breath out. The stabbed man stands up, smiling. Someone puts a coat around him. People begin to bustle about, moving lights, talking into headsets. But I stay, looking at the blood on the concrete. Fake this time. Syrup and food colouring. But fifteen years before and the blood had been real. The blood had been mine.

I was fifteen and we had been heading to a youth club near my school. They would sometimes set up disco lights and try to turn the hall into a mini nightclub. DJs would bring their records to spin on the decks, and there was a microphone too. This was around the time that garage was coming up and I fancied myself as an emcee. A few kids in

4 my class encouraged me to get involved, as they knew I had been writing to and rhyming over jungle beats for a while, so they wanted to hear what I had. A few of us stopped at an off-licence, as we usually did, to try and buy drink. Sometimes we would get served or find someone else to buy it, but other times the shopkeepers were having none of it. I can’t remember if we were successful or not, but I recall leaving the shop before my friends and heading off towards the youth centre. That night, I was eager to touch the mic.

I must have got about 20 metres up the road, and when I looked back, I saw arms flailing and heard shouting and arguing. There was some kind of disagreement with two bigger men. I started walking back to the shop to see what was going on.

When I reached them, I stepped forward, put on a screw face and tried to make myself sound more aggressive. But they could hear the reservation in my voice when I tentatively asked, ‘What’s going on? What’s the problem?’ The sweetest right hand to the centre of my face let me know that my intimidation ploy had failed miserably. The connection from the punch sent me to the floor. Me and my friends tried to put up somewhat of a fight, but our little secondary school selves didn’t stand a chance. We got dispatched.

I remember seeing one of my boys go airborne and another getting dashed on to a car. I was being held in a headlock. While still struggling to break free from this grown man’s grip, I heard the sound of smashing glass,

then I received another heavy blow to where the top of my neck meets the back of my head. I managed to break free and the fighting continued. A few more punches were thrown and a couple more tussles took place, but the adults definitely got the upper hand. They exchanged a few words that I couldn’t follow, then quite suddenly, they took off and the fight was over.

My adrenaline disappeared immediately and from nowhere I felt the pain kick in. Sharp and impossible to ignore. The looks of horror on my friends’ faces told their own story. One of my friends started screaming out repeatedly, ‘Oh my God.’ The other started crying and screamed, ‘Your head’s fucking hanging off, Ash!’ It sounds hard to imagine, but I could actually feel it flapping in the wind. It felt like someone had poured a bucket of warm water all over my head. I looked down and my bright yellow Iceberg T-shirt was covered in red. We started walking to see if we could find a phone box to call 999. That’s when the seriousness of the situation hit home. My friends knew I needed an ambulance but I was unable to speed up. I could feel my energy fading and I was starting to move slower and slower. My friends tried to speed up the walk and usher me along faster, but they could see my life battery draining. My vision faded away into a tiny circle and I blacked out.

‘Ash?’

I jerked back to the present. ‘You coming?’ I nodded. The producer walked towards a car. But I couldn’t look away. A lot had happened in those fifteen years. A lot more

6 has happened since that night when I stood staring at that dirty patch of red on the concrete. But if this book is about anything, it’s about how that fifteen-year-old went from lying bleeding on the concrete in Pimlico to filming a TV show in Hackney. Because that journey might only be 7 miles on a map, but trust me, it’s a lot longer.

Life is all about choices. Different people get different ones. You don’t get to choose your family, or how big their house is, or how much money they have in their bank account. And no one is going to pretend those things don’t matter. No one is going to pretend that life isn’t different for the kid whose dad is sent down to the kid of the barrister who defends him. Or that there’s no difference between an estate with deer and one with dealers on it. This world isn’t fair. But everybody, and I mean everybody, everybody gets some choices of their own.

My only qualification for writing this book is that I’m someone who has made bad choices, who has learned how to make better ones. I’m definitely not setting myself up as perfect. As you’ll soon see, I’ve made mistakes. Lots of them. One of my biggest regrets is where my family is concerned. I had my first child when I was seventeen. I became a grandfather at thirty-eight. I’ve always tried my best. But I know that I haven’t always been around, and when I have, I haven’t always been the best version

of myself. I can’t go back in time and make that right. All I can do is make sure from this moment onwards, I do the right thing. I believe that my mistakes led directly to this moment: you reading these words on this page. I can make peace with that.

A month after I was standing onstage winning a BRIT Award, I was standing in a dock being sent to a young offender institution. Fame and fortune. The whole world, stretching out in front of you. Then you’re in a concrete box that smells of piss and bleach. When you’re nineteen years old, sitting in a cell, listening as all around you inmates scream, ‘Oi, Asher. You are dead tomorrow morning, mate,’; ‘Pussy hole, this is your last night of life,’; ‘Ash, see me at breakfast,’; ‘It’s on when I catch you, watch!’; ‘You’re on your own now, boy. You’re done out here, dead!’ And bang on their cell doors till it feels like the walls are falling in, you have plenty of time to think about your life and how you got there. As part of So Solid Crew, a musical collective who made as many headlines for being reportedly one of the most infamous gangs in the country as we did for our music, I knew I had a target stuck to me. They would want to test my gangster credentials, make a name for themselves. I’d seen them watching me as I walked down the landing, their eyes at every cell I passed. I’d been on the BBC news that night as I was booked in.

Some of the elders in So Solid had told me they’d come and they’d come with weapons, so be ready. I sat on my

8 bunk, afraid and then I started to get angry. It wasn’t fair, that I was sitting there. Yes, I’d been stupid. Who tells a traffic warden they’re going to put two hot ones in them?! I had a gun in the front of the car. I had my kids in the back of the car. I had pleaded guilty. Bang to rights. But that only felt like part of the story. I felt like I had to have the gun. When you grew up where I did, you needed to keep yourself and your family safe. My family and I had been threatened. The threats of violence at So Solid gigs was getting so I would leave straight away.

My whole life, violence was everywhere, the sea you swam in. You couldn’t grow up and not know people caught up in it. I couldn’t go to some areas because of what might happen if I did. It’s just the way things were. My dad had me in the car when he was trying to escape the police for God’s sake. What did people expect? They didn’t know. They didn’t know what real life was like. For people like me. I felt anger flare. I was angry at the wardens for letting the other inmates threaten me. At my barrister for his weak plea that I was a victim. At the judge for the sentence. I was even angry at my partner for agreeing to carry the gun in her bag. All those people shaking their heads at me in disappointment. Fuck them and fuck those prisoners shouting.

The next day I would find any boys from my area to hang with and make sure I could protect myself. If someone came for me they’d see what they’d get. I felt the anger fill my chest and I got ready to scream it out. But

then I saw the face of the old woman who had been raging at the police as they arrested me, telling them to let me go, berating them for how they treat young black boys. I had let her down. I saw my mother’s face, my grandmother. I had let them down. I thought of my son and my daughter. My baby girl who had taken her first steps twelve hours earlier. What if the armed police had thought I was a threat and had opened fire? What if they’d been hit? Luckily we followed their instructions and that didn’t happen. But it could have done. I’d never have been able to live with myself if something had happened to my kids. And now they had to do without their dad for all this time.

Then suddenly the anger went away and there was just sadness. And as I sat there, I realized what a dead end blaming where you came from was: how you grew up, what you didn’t have or didn’t learn. Don’t get me wrong, I understood. I’d seen plenty of people who felt the world wasn’t set up for people like them and saw time inside as a badge of honour. They got sucked into that spiral of reoffending and that’s it. Doesn’t matter what your gifts and talents might have been. I thought of all those other boys who had sat in this room. Feeling afraid. Feeling angry. Starting down that pathway. If the world that everyone else lives in isn’t made for you, then crime is where you put your ambitions, where you find belonging and respect.

My mind flicked back to what might happen in the morning, to those threats made real and how I would

10 defend myself. I felt helpless. But I decided that I would stop focusing on the things I couldn’t control and I would focus on me. I would try and make myself better. Because the one thing I could definitely control was my mindset. Those inmates in those cells were going to do what they were going to do, whatever I thought about it. But I could choose to not let fear define my time there. The next morning, I walked out of my cell and nothing happened. There was no attack, no weapons.

Over the following months, I took courses, wrote lyrics, hit the gym and collaborated on positive projects with fellow inmates. We were right under the flight path for Heathrow and hundreds of times a day we would be reminded of the freedoms that others enjoyed. I kept my head down, stayed humble and worked on turning my whole life around. I turned my back on violence and reputation. I let others say whatever they wanted to say and focused on getting out as quickly as possible. I kept my head down, and what became Always Winning began to take shape in my mind. It began with one idea – if I can transform any situation into an opportunity to get better, to try harder and learn, then I can never lose. With the right mindset, I can use even the biggest setbacks, like sitting there in that prison, to propel me forward. Over the almost twenty-five years since that night, I have built upon those ideas. I might be truly ashamed by the fact I was ever in that cell, but I will always be grateful for the seed that was planted in that long fear-filled night.

WHY ME?

When I was growing up, books like this didn’t get written for me. Books like this certainly didn’t get written by men who looked like me. So firstly, I wanted to write this book for that person now who feels like the world doesn’t understand what life is like for them. I want to be honest about where I have been and how I have got to where I am. Because we can’t be what we can’t see. I want my children to grow up in a world where books like this do get written by men who look like me. More than that, I want them to know about me and what I’ve been through. But I believe that whoever you are, whatever your background is, there are things I’ve learned along the way that you may find useful. You might not have cells full of prisoners threatening you, but you have things you’re scared of. You know how fear of failure can stop you trying. We all face setbacks. We are all tested. We get knocked down and have to find the strength to get back up. We all have to deal with failure and disappointment. And success, which can sometimes be the hardest thing of all. We all procrastinate and get distracted. We all get trapped in patterns, doing things that we know aren’t good for us and ignoring the things that we most want to do. We have to find our way through life and be proud of the decisions we have made. We can’t control everything, but I have come to realize that the sort of life we have is defined by focusing on the things we can control.

12 Always winning means accepting that the things you can change are more important than the things you can’t. It means understanding that both victories and defeats are fleeting moments and we shouldn’t spend too much time on either of them. It means understanding that the only constant is change and unless you embrace that, life is going to be a constant struggle. You have to be willing to adapt, to grow, to bend, or you’re going to break. You’re also going to have to get used to failure. Failure is the price of the ticket to success. There’s no getting around it. We must learn to welcome times of hardship. How we perceive and react to life’s most difficult and challenging moments makes us who we are. The more temporary defeats we face and overcome, the stronger and more resilient we become. We may be able to identify problems before they happen and avoid them, but mostly those failures are just part of the process.

Roger Federer recently gave a speech where he pointed out that over the course of his career, he had won only 54 per cent of the shots he had ever played. One of the best tennis players ever to have lived. Half of the shots he played failed. But he went on to say that he had always concentrated on the next point, whether he’d won or lost the previous one. And that’s what had allowed him to win 80 per cent of the matches he played. Freeing yourself up from worrying about every point means you can win the ones that matter. I was in prison for seven and a half months. The average male in the UK gets something like

960 months of life. Am I willing to be defined by less than 1 per cent of my life? No. You lose a point. Fine. Learn from it. Move on. Play the next one.

I once went up for the lead role in a biopic of Sam Cooke. I wanted that part so badly. I did so much research and I took months of singing lessons. When I heard I hadn’t got it, of course I was disappointed at first. But I was able to see that the work I’d done wasn’t wasted. The research, the preparation, the process, that is the victory. I learned to sing and I will always have that. Every project, every part, every process. It was all a step on the journey to who I am right now, in this minute. I have been lucky enough to make a career out of trying to tell stories about characters who all too often get reduced to one-dimensional cut-outs if anyone pays attention to them at all. I spend a lot of time thinking about what matters to them, what motivates them. Too often we ignore the potential we all have to change and to make ourselves better.

This book is the crystallization of everything I’ve learned. Seven rules that I try to follow to keep my mindset right:

Always know yourself, then be yourself

Always believe in yourself

Always give your best

Always face your fears

Always know your poison

Always fail better

Always make suffering your friend

14 It can be hard, especially in the industry I’m in. So many of the big decisions feel out of your control. If I lose a big part, or a project we’re trying to set up fails, I can slump back into blaming the system. And if you feel like that too, I get it. It’s just a fact that not everyone is dealt the same cards. Is it fair that those of us who come from backgrounds where we don’t have things handed to us, have to be twice as good and work twice as hard as those who do? No. But I’ve never wanted to sit on my hands waiting for that to get fixed. I believe that if the world is set up not to give you a chance then the only thing you can do is go and take that chance for yourself. A word that comes up a lot when people talk about my acting is ‘authenticity’, and I think what people mean is that it feels like I still live in the same world as the characters I play. I think they sense that I want to do right by characters that are often limited to stereotypes, when they feature in our stories at all. I want to honour people who have been told that their lives don’t matter. I believe that all of our lives matter. My life has been shaped by extreme experiences that I hope no one holding this book has to face. But they have helped me understand that whatever situation you are in, we all have the same equipment, the same brains, the same impulses. Whatever your background, the one thing no one else can ever control is how you choose to see the world. Nobody can take that away from you.

CHAPTER 1 ALWAYS KNOW YOURSELF, THEN BE YOURSELF

‘BRUV, WHAT THE FUCK IS OLIVER ?’

I looked at Kez and felt my chest tighten. Tried to look casual. ‘What’s what?’

‘Nathan’s little brother went to Leicester Square and swears down he saw your face on a poster. For a thing called Oliver.’ He was looking at me, smiling but watching me carefully.

I was thirteen years old. Kez was a mate from my area in Peckham. We’d grown up together and I trusted him, but I also knew I had to be careful. Where we lived, it only took one thing and you would never live it down. That would be your reputation forever. People placed a lot of importance on reputation. Everyone we respected was known for being strong, no-nonsense and not taking shit from anyone. They had respect and that came from being able to handle themselves. If they found out that I was regularly travelling up from Peckham to go to the Sylvia Young Theatre School and learning ballet and tap dancing, that would be it. At first I’d gone with a close friend,

18 whose mum was best friends with my mum. One day, his mum wasn’t around, so my mum took him to an open audition and I tagged along too. When we arrived, the casting assistant asked, ‘Are both boys trying out today?’ My mum said only he was auditioning, as all children were performing rehearsed material and I hadn’t prepared anything. ‘Just let him sing “Happy Birthday” then.’ So I sang it and landed my very first role, performing at the Prince Edward Theatre, playing Abel in a musical called The Children of Eden . I’d kept going, I’d done more plays, some adverts and even a couple of tiny parts in TV shows. But I’d managed to keep my two worlds entirely separate up until that point, even though my mum had been taking me up there since I was seven. It was a miracle this hadn’t happened before really. But now I was busted. I thought about my options. I could lie. I could tell him Nathan’s little brother was chatting shit, or confused, or that it was just some kid who looked like me.

But in the end I told him. I was doing a bit of acting now. The money was good. And he just nodded.

But it wasn’t the first time that I felt pulled in different directions. I’ve never been a ‘real’ bad boy, I just happened to grow up in one of the UK’s most notorious areas. I knew a few people, but I was never really ‘active’ or involved in the real gang shit myself. I was a Peckham boy, not a ‘Peckham Boy’. But you couldn’t escape it. I grew up right on the border of Peckham and Camberwell. I lived in social housing with my mum and Jacob, her partner