ALLEN LANE an imprint of

ALLEN LANE an imprint of

Edited by Ted Widmer

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Allen Lane is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Penguin Random House UK One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published in the United States of America by Liveright Publishing Corporation, an imprint of W. W. Norton & Company 2025

First published in Great Britain by Allen Lane 2025 001

Copyright © MPL Communications Limited, 2025

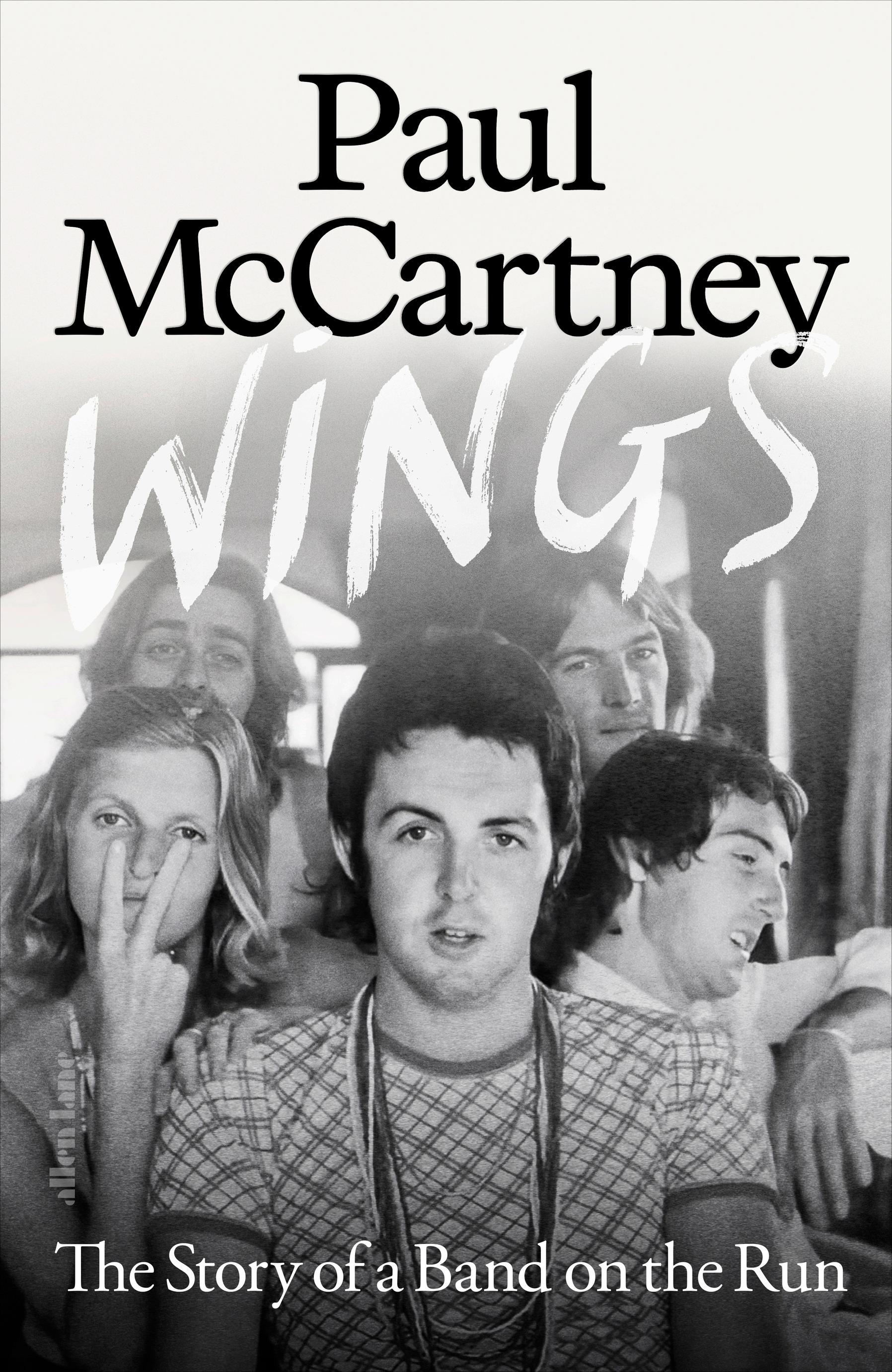

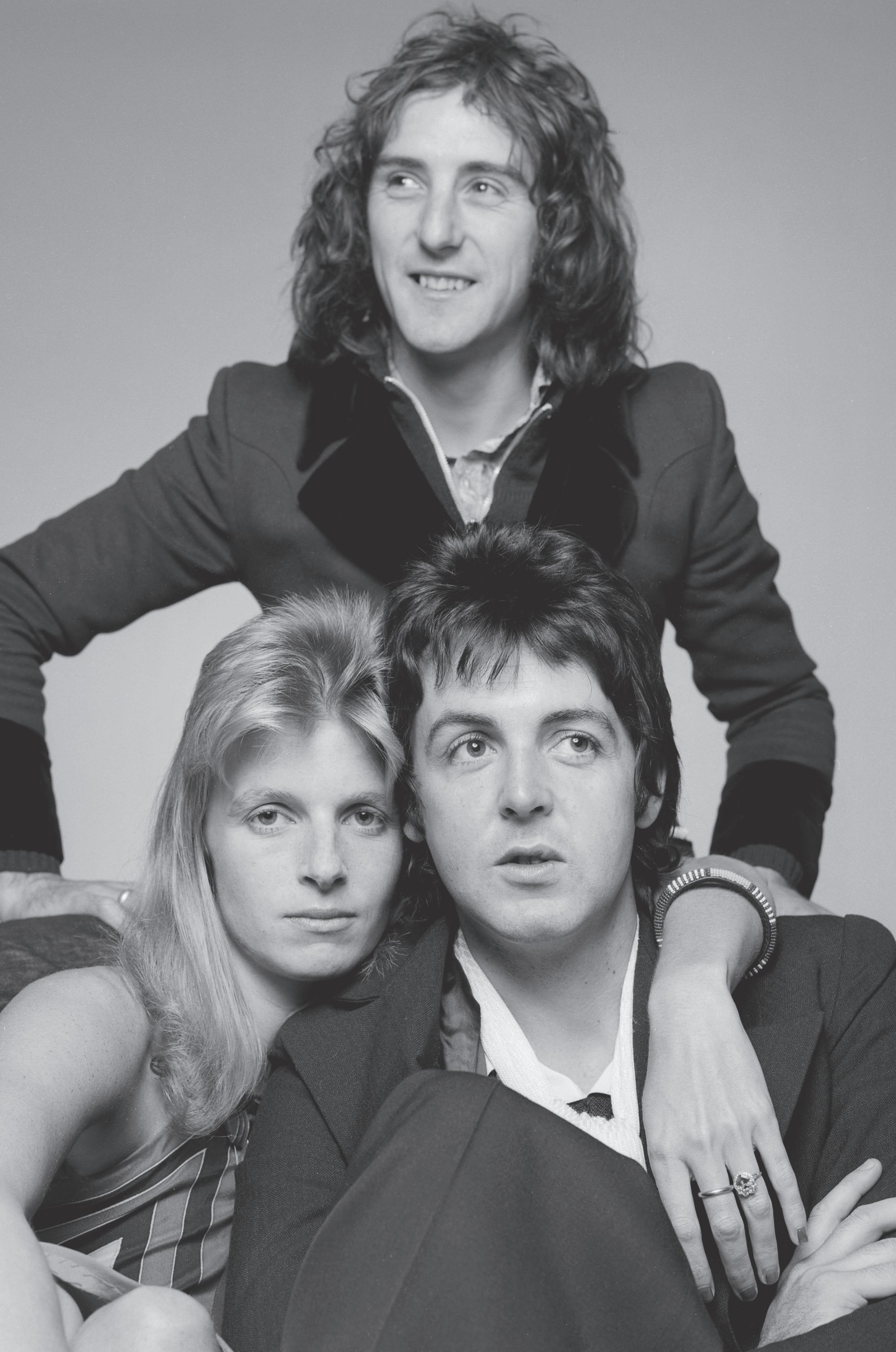

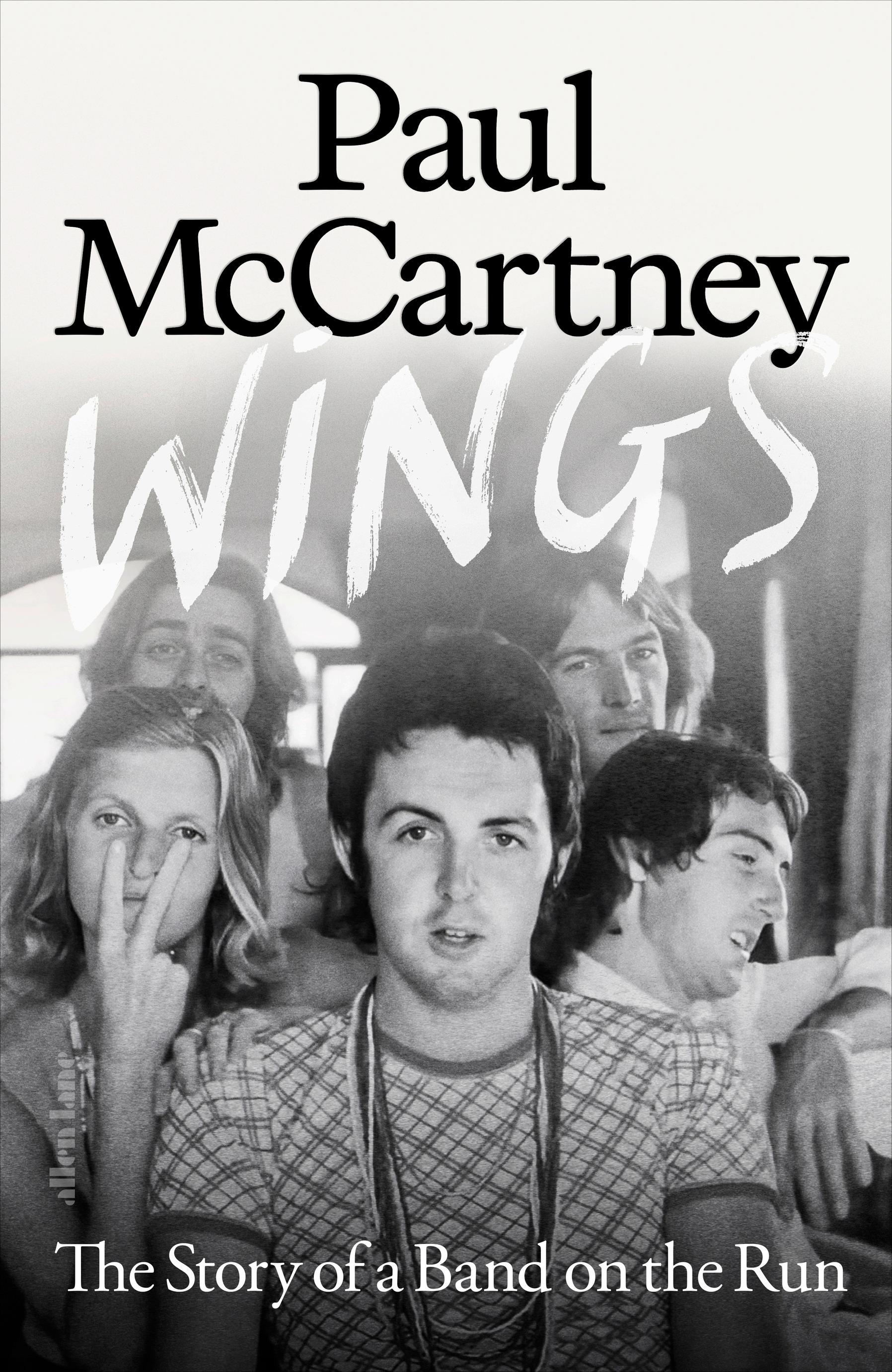

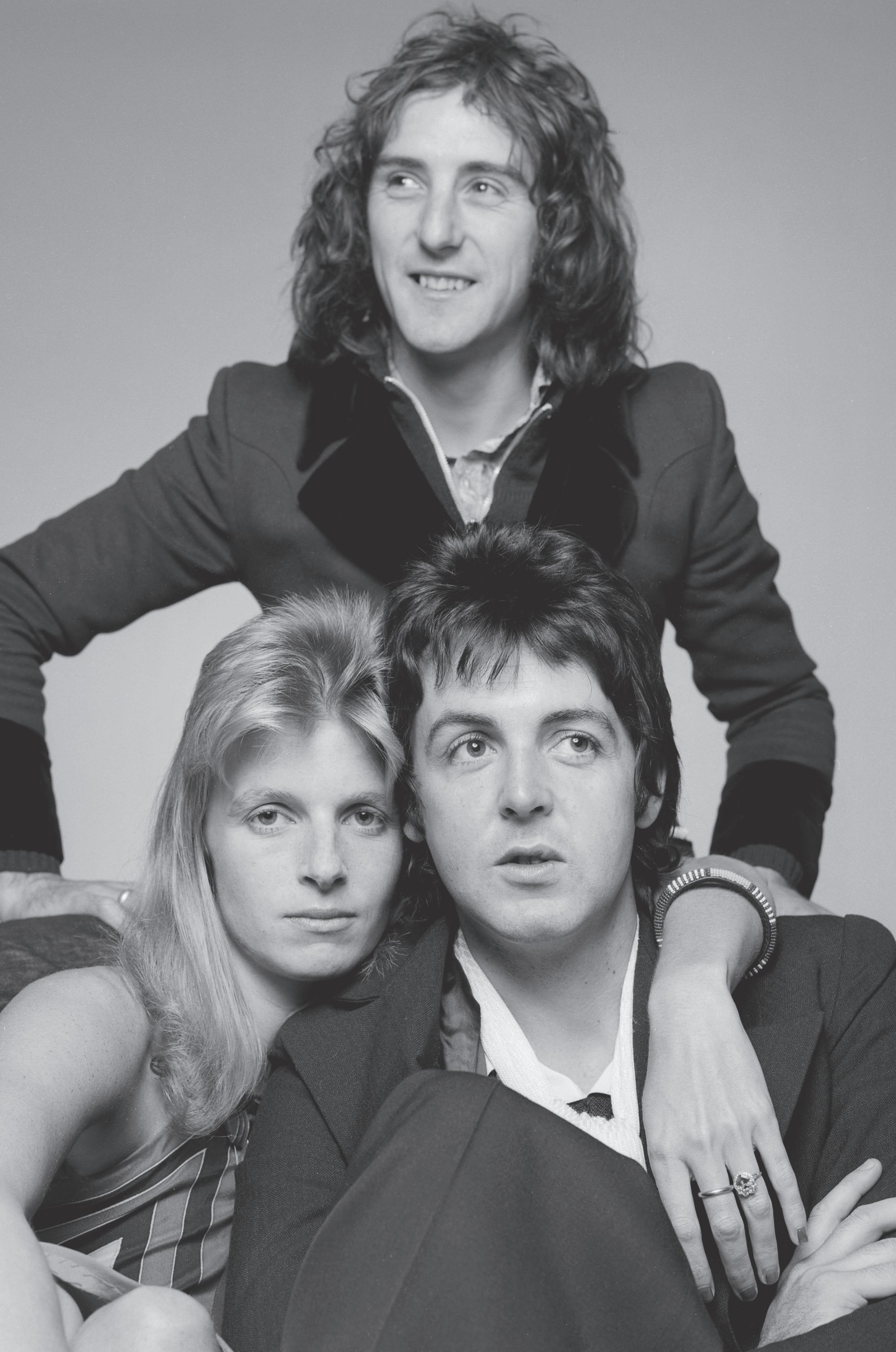

Frontispiece: Linda McCartney, Denny Laine and Paul McCartney, promotional photo shoot for Band on the Run, 1973

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978–0–241–75857–1

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

Foreword viii

by Paul McCartney

Editor’s Introduction xviii

by Ted Widmer

Cast in alphabetical order xxi

PART I: 1969– 71

Chapter One: In My End Is My Beginning 2

Chapter Two: RAM

PART II: 1971– 73

Chapter Three: Wild Life

Chapter Four: First Flight

Chapter Five: Red Rose Speedway

PART III: 1973– 75

Chapter Six: Band on the Run

Chapter Seven: Venus and Mars

PART IV: 1975– 78

Chapter Eight: At the Speed of Sound

Chapter Nine: London Town

‘Well, the rain exploded with a mighty crash as we fell into the sun.’

THE STRANGEST RUMOUR STARTED FLOATING AROUND just as The Beatles were breaking up – that I was dead.

We had heard the rumour long before, but suddenly, in that autumn of 1969, stirred up by a DJ in America, it took on a force all its own, so that millions of fans around the world believed I was actually gone.

At one point, I turned to my new wife and asked, ‘Linda, how can I possibly be dead?’ She smiled as she held our new baby, Mary, as aware of the power of gossip and the absurdity of these ridiculous newspaper headlines as I was. But she did point out that we had beaten a hasty retreat from London to this remote farm up in Scotland, precisely to get away from the kind of malevolent talk that was bringing The Beatles down.

But now that over a half century has passed since those truly crazy times, I’m beginning to think that the rumours were more accurate than one might have thought at the time. In so many ways, I was dead . . . a twenty-seven-year-old about-tobecome-ex-Beatle, drowning in a sea of legal and personal rows

viii Foreword

that were sapping my energy, in need of a complete life makeover. ‘Would I ever be able to move on from what had been an amazing decade?’ I thought. Would I be able to surmount the crises that seemed to be exploding daily?

Three years earlier, I had bought this sheep farm in Scotland on the suggestion of one of my accountants. At the time, I wasn’t very keen on the idea – the land seemed sort of bare and rugged. But, exhausted by the business problems, and realising that if we were going to raise a family, it would not be under the magnifying glass that was London, we turned to each other and said, ‘We should just escape.’

Looking back, we were totally unprepared for this wild adventure. There was so much we didn’t know. Linda would later go on to write famous cookbooks, but at first – and I’m a living witness – she was not a great cook. I was hardly any better suited for rural life. My father, Jim, still in Liverpool, had taught me many things, especially how to garden and love music, but putting down a cement floor was not one of them. Still, I wasn’t going to be deterred. So, I got a guy to come up from town who taught me how to mix cement, how to lay it down in sections, and how to tamp it to bring the water to the surface. No job seemed too small or too large, be it cutting down a Christmas tree from the local forest, making a new table, or getting on a ladder to paint an old roof. A big challenge was to shear the sheep. We had a guy called Duncan who taught me how to use old-fashioned shears and put a sheep on its haunches. Even though I could do only ten sheep to his hundred, we were both knackered by the end of the day. I took great satisfaction in learning how to do all these things, in doing a good job, in being self-dependent. When I think back on it, the isolation was just what we needed. Despite the harsh conditions, the Scottish setting gave me the time to create. It was becoming clear to our inner circle that something exciting was happening. The old Paul was no longer the new Paul. For the first time in years, I felt free, suddenly leading and directing my own life. I was not conscious at the time of moving away from the long shadow cast by The Beatles, but that was exactly what I was doing. And in creating

these early songs that would become part of McCartney, RAM, and Wings’ early songbook, I was doing stuff that I hadn’t been able to accomplish in the past.

Essential to this newfound freedom and success was Linda. On the surface, she and I came from very different backgrounds. On a deeper level, though, we had both been preparing for this journey, this escape to Scotland. She had had a pretty conventional upbringing, growing up in quite a traditional family in Scarsdale, which had not the slightest resemblance to Liverpool. She was supposed to have become a society wife, with the right number of children, going to the right schools, and all that, but she wanted to break free of the strict life that had been laid out for her. At first, she got into photography and loved the freedom that came with it; at an early age, she became a big expert on the rock and roll explosion, so much so that she often knew a lot more than I did. But my own journey complemented hers in so many ways, particularly in the way we were both so curious and self-reliant. While my fellow Beatles bought big houses and escaped to the suburbs, I decided to stay in London and absorb as much of the sixties culture as I could – visiting the theatre, hanging out with and learning from avant-garde composers, experimenting with tape loops, helping to set up the Indica Bookshop, where we’d get to hang with folks like William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg, or going to the home of Bertrand Russell for a chat. Without even knowing it, the paths of Linda and me, while on the surface so different, were strangely converging – at first in London, where we met, but here in High Park, where we would raise our family and create a new band which would help shape my artistic life for the rest of my career, including a wide range of Wings songs I still play in my current set.

For so many decades, I tried to pack away these stories about how I felt when The Beatles collapsed and what happened in that period just as we were launching Wings. Like everything else, it’s a timing thing. Nobody had specifically said, ‘Let’s do a

x Foreword

Wings thing.’ But suddenly, Wings has found its moment again. I remember doing an interview with a young guy, I think it was with Rolling Stone, and I was talking about Sgt. Pepper and The Beatles, and so on, and so on. And he said, ‘Well, yeah, I get that, but that’s really not my period.’ He said, ‘I’m more interested in Wings and Band on the Run.’ I thought, ‘Here we go. We have a generational shift at work.’ That’s his nostalgia period, and it’s not the sixties, and that’s sort of what’s happening with a lot of people, and with Morgan Neville, too. Morgan, the documentary filmmaker who’s done 20 Feet from Stardom, was definitely one of them, so I met with Morgan and found him smart and personable. He was asking all the right questions, so I was very happy to be transported back, like being on a magic carpet, into that period. It awakened so many beautiful memories for me of our times back then. Without question, it was Morgan’s own fascination with Wings that stirred up my own interest in the Wings story.

One significant aspect of this book is that Ted Widmer was given access to all the documentary recordings (which turned out to be hundreds of thousands of words), but we did not want him to see the film, because we hoped that the film and the book would proceed in two creative directions, not entirely alike. I’ve loved books and literature since I was a kid, and I had one particularly good English teacher, so I know there’s something magical in using plays, books and accounts to reclaim a period. And from the time when I was hanging out with poets in London, I always wanted to push creative forms, never trying to repeat what everyone else was doing. So, the idea that someone is going to take these Wings stories, which to me are just my memories, and research them and go more deeply into them than I ever could becomes flattering, to say the least. I’m convinced that this chorus of voices, whether presented in the documentary Man on the Run or here in the book, produces a history – a Wings bible, if you will – that not only recalls the period but presents a new art form all its own.

The book is filled with all kinds of lovely details, many which I have not thought of in over fifty years. It’s best that they

Foreword xi

be fully related in the oral history that follows, but a few things are worth mentioning here. People often ask me about how the Band on the Run title came to me. I recall that around that time, a lot of young people, especially in America, were feeling this kind of hippie desire to be free from so-called chains, as if we were desperadoes busting out of jail. You’d see bands emulating this sort of thing, where they would be on a porch, looking like old cowboys from the nineteenth century. I thought, ‘Yeah, we’re desperadoes, we’ve just broken out of prison, what an idea for a song.’ I wrote about being ‘stuck inside these four walls’, and then we escaped – boom, boom, boom – and we’re now out. It just summed up this freedom, with ‘Band on the Run’. Just catch us if you can.

Back then, we were young people trying to find a new way, trying to find our own identity, rather than just doing what we were supposed to be doing, so I felt like a lot of people could identify with us – and can still identify with Wings today. A lot of this meant that we just could not do something in normal style, as in the standard way that groups were being transported around England or Europe. Most would, you know, just get a little van, or a school bus, but we searched for and found a double-decker bus. It was built in 1953, though we painted it psychedelic to match the newer times. Some people believe I managed to take the top off myself – which, I’ve got to be honest, remained beyond my skills – but we liked it because it already came that way. We thought, ‘Well, that’s perfect, we can be downstairs – indoors, that is – if the weather is poor, and upstairs if it’s great.’ The bus said, ‘Wings Over Europe’, and we took the kids along, and there’s that great picture of us all sunning ourselves on the top. Almost without knowing it, we were in a period when we didn’t need to explain ourselves. That was one of the great things. I do remember that when Linda joined Wings, eyebrows were raised, and not only in the press, Mick Jagger adding, ‘What’s he doing, getting his old lady in the band?’ But in the end, no one can deny that it worked out great, and we felt that a lot of young people could identify with us. The fact was that we could just try things and just do them. If it worked, great. If it didn’t,

Foreword

just go to another idea. Our trip to Lagos in 1973 to record Band on the Run did not begin auspiciously. As you’ll discover, we were mugged and could have been easily killed, and our tapes were stolen. It’s true that ‘the rain exploded with a mighty crash’, but we survived, and in the end, ‘we fell into the sun’.

It’s important for those who care about history, particularly rock history, to realise how important music can be as a form of social protest. No one should forget that songs and lyrics, especially during dark and troubled times, can create awareness, be used to arouse indignation, even bring about social change. I remember how moved both Linda and I were by the events of Bloody Sunday back in January 1972, when British soldiers shot several dozen unarmed protest marchers. Since my own family goes back to Ireland, this massacre in Northern Ireland made me ashamed of Britain, ashamed of what we would do, and I had a genuine feeling that we had got this wrong, that we had to give Ireland back to the Irish. I knew that if I wrote a song, my views would get out there and people would hear about it. But we got banned by the BBC, which would not play ‘Give Ireland Back to the Irish’, and our guitarist, Henry McCullough, was threatened because he was from Northern Ireland. The nice thing was that the song went to number one in Spain, and looking back, I have no regrets.

At the same time, it’s worth pointing out how songs and music can work the other way, bringing people together from completely different ideologies. In this respect, I think of the time when our Wings Over the World tour played Zagreb, behind the so-called Iron Curtain. The fact is, they’re just music fans, too, and that’s how your message gets over. They hear what you’re saying in your song, and without saying anything illegal or doing anything wrong, they’re agreeing with you, so that the song becomes an idea, or even an anthem.

I’ve now had over sixty-five years of touring, and I’ve come to realise more than anything that people across the world are very similar. They’re all, simply said, just people. They like the idea of coming together, they like the idea of love. And the more you look at the world, it’s the same everywhere. You think, well,

Foreword xiii

China would possibly be different, Russia would be different, or, I don’t know, Africa would be different. But it isn’t. It’s all the same thing. We’re all just these human beings, wanting love. And I always hoped that Wings would reflect that kind of love. I was very proud that it did.

After that soul-searching time in the early years, having to prove that I could exist outside the cage of The Beatles’ fame, we were flying. Wings Over the World was true to its word, not only in the States, where we celebrated America’s two-hundredth birthday, but all over the world. Yet, three years later, the euphoria was no longer there. The end of Wings would become a drawn-out affair, lasting another two or three years. You just have a hot period, and then after a hot period comes a cooler one. It’s nature, it’s science; things just seem to fizzle out. Wings’ success was quickly followed by a period when I wasn’t that happy with the lineup and what we were doing with the group at the time.

Some people think that the end of Wings came only in 1980, that that was the end of the movie, when I was busted for pot and served nine days in the Tokyo Narcotics Detention Centre, but the truth is that the inspiration had already begun to move elsewhere. You can’t force it; you just have to recognise that everything comes to an end.

My real interest today is not in the bust itself, but how we perceive it in memory. When I got back to England, I scribbled down my own memories and wrote a little book for my family, but I just left it there. So, now I like the idea of Morgan Neville going back to this period that I’d left behind, thinking that I’ve moved forward onto the next thing, but these events, these life traumas, just don’t go away. I find it fascinating that there’s a comment in the book from one of the Japanese jailers, who turned out to be very nice. This little detail triggers memories of all the little personal details that I had long since forgotten, like being in jail in a foreign country and not knowing if you could get a change

xiv Foreword

of clothes. Only now do I recall being told that you could ask people to bring in fresh clothes, and I was able to ask Linda if she would bring me in a tracksuit so I could get out of the green suit that I had been wearing for days.

When you think of all the drug taking, of the deaths of many of us – from Jimmy McCulloch, to Hendrix, to Joplin, to Keith Moon – you realise we were lucky, but it was more than that: we avoided the hard drugs, and most of all, it was family. The fact was that Linda and I now had kids who were growing up. A lot of others didn’t have these kinds of responsibilities. We could no longer go out late. We had to avoid the insanities. Because you had children, you wouldn’t do drugs, and you couldn’t drink as much, either.

While few people like to talk about age or to think about the physical or even mental infirmities they inevitably bring, there are many positives as well, as both the documentary and this book reveal. Just as I rebelled at the end of the 1960s at being branded with the stamp of BEATLE on my forehead, I also knew that the independent impulses that drove Wings, as you can see from this story, could not last forever. All these passages of time give us a richness of perspective that I’m particularly aware of now. Shakespeare writes about the ‘mercy of a rude stream’, a phrase I kind of like because it says that if we’re lucky, we can find mercy at the end of the rude stream that is life. In this regard, I think of RAM, the album that Linda and I put out just before Wings, but which I know John and Yoko took offence at the time. Looking back, it was really just a lot of turbulence. We were family. Families do argue, brothers argue. And once you realise that, you can look back with mercy and think, ‘Oh no, it was really beautiful,’ even though it was sometimes chaotic, sometimes disappointing, even sometimes very sad. But time allows us to appreciate that, on other occasions, our relationship was very happy, ultimately successful. I can think of one case when Yoko asked me and Linda to rescue John after they had separated and he had gone to the West Coast. I was happy to do that, to bring him back to his true love. It was an emotional duty, that’s how I felt, that I could sit him down and say, ‘Yoko

says she’ll take you back if you go back,’ and I’m very proud that it happened that way.

The press liked to portray us as constantly quarrelling, but we were really empathetic people. We hardly wanted to rule the world or destroy anyone’s life, and in John’s case, I think the answer was love. He was madly in love with this girl, and people do crazy things when they’re in love. And one of the most wonderful things that came out of that weekend was that they went and had Sean. I’m very glad that John heard me.

Over a half century has passed since the formation of Wings, and it pleases me that people remember the songs, and that many are still coming back. I’m now at an age that no young person can ever imagine they will be, but it’s that passage of time that fascinates me, that presents a prism through which we view life differently, with far more kindness and love. And we look for routines, much as Picasso did when he was ninety-one and ninety-two, making over a hundred paintings a year. My own regimen is pretty straightforward. I take great pleasure from routine. I get up, and I take some vitamins. I have a very specific kind of breakfast, with fruit and cereal. I probably go to work – drive twenty minutes to my studio and play some music.

If I am not going to the studio, I will sit around with a guitar and piano – that’s if the mood takes me – because that is what I know. And magic appears if you are lucky. At three o’clock, if there are words on a piece of paper, and there’s this song you’ve written, it’s a great feeling. It’s such a great feeling that I can do anything else I want for the rest of the day – that is, until evening, when Nancy and I will come together and have a meal and just relax before I close up the house for the night.

I feel very lucky when I get an inspiration. A lot of people will never have them, but I’ve been lucky to have had some form of inspiration, even if it was just as a kid in school. I was always creative. I remember thinking of a poem, I can barely remember it now, but it started off with a worm chain dragging slowly, and it was about humanity disappearing. This is my vague recollection:

xvi Foreword

The worm chain drags slowly

And disappears into a hole in the ground

Then reappears on the backs of the young

Man tell the woman

Her children are crying

The trouble with living Is nobody’s dying

So, I wrote that one when I was twelve or something, and tried to get it into the school magazine, which turned it down.

All my life, and even then, I wanted to do something different. For me to succeed, it had to be different. I wanted to write songs, and I did them, but over time, it becomes a body of work, even without realising it. And right now, I have twenty-five songs that I’m finishing in the next few months, new songs that are interesting. I can hear something, I can hear a piece of music and think, ‘Oh, I love that,’ and I’ll incorporate that feeling into a new song. And often, a constant thread through my writing is nostalgia, the memories of things past.

I don’t question too much how it happens. I’m just thrilled that it does.

Paul McCartney

London March 2025

Foreword xvii

THIS BOOK, AN ORAL HISTORY, IS ABOUT Paul McCartney’s musical odyssey across the 1970s, and the remarkable players who joined him in Wings, beginning with his wife Linda. With great single-mindedness, Paul included his family every step of the way as he reinvented himself as an artist. It is also about the other members of Wings, and a large supporting cast of producers, engineers, session players, promoters, album designers and family friends.

It required diligence to track down the details of a band on the run. MPL provided just that, co-ordinating research in both Britain and the US and helping to find contemporaneous interviews that would convey the band’s colourful story. Shakespeare assures us that knowledge is ‘the wing wherewith we fly to heaven’. It was a particular joy to hear Linda McCartney speaking again, a brave female voice in the mostly male enclave of rock and roll.

An important set of interviews was conducted by Morgan Neville for his Wings documentary, Man on the Run. They are the marrow of the book. The interviewees opened their hearts and spoke candidly about the peaks and valleys of a great adventure.

xviii Editor’s Introduction

Where we have needed to fill in the gaps, we turned to historic interviews and interviews conducted for previous MPL projects. It is a story that moves through space as well as time. Wings were fearless in the early years, hitting the road constantly, from the University Tour of February 1972 to the epic Wings Over the World tour of 1975–76. They travelled to many exotic locations for recording purposes. At the end of the decade, they were still trying to bring their message to new places. That, of course, is why they went to Japan.

There were setbacks, including Japan, but in the end, it is a story of optimism, creativity and resilience in the face of life’s slings and arrows. Even in a dark time – and the seventies had darkness as well as light – a way forward can always be found. A lyric from ‘Power Cut’, about an electricity shortage, cuts to the chase:

There may be a power cut

And the candles burn down low

But something inside of me Says the bad news isn’t so

We consider the story of Wings to include Paul’s first solo album, McCartney, and his second, RAM, released by Paul and Linda McCartney, but featuring a drummer, Denny Seiwell, who went on to join Wings. Chronologically, these two albums precede Wings, but we all agreed that they were Wings-adjacent, as was McCartney II, which came out in May 1980, as Wings neared their end.

Some albums were released as Wings, and some by Paul McCartney and Wings. We consider them all part of the same story. For the formatting of the band’s name, we have chosen the wording on the UK disc labels.

The written record from this period of time can sometimes be a little hazy when it comes to release dates. Where there was any uncertainty, we have done our best to ascertain the closest likely date. We offer timelines within the chapters, as well as

Editor’s Introduction xix

band biographies, a discography and a gigography at the end of the book with editorial written by Pete Paphides. For the Key Releases we have included an introduction to the albums and non-album singles released by Wings. We have also included a Selected Discography where we take a more comprehensive look at the releases from the period. When citing a record release, we included the date of the first release, whether in the UK or US. We have also included details of some of the best-selling albums for each year. This is not meant to be an exhaustive list, but to give an impression of what was popular and the change in trends. We wish to remind readers that many of the events described in this book happened more than fifty years ago. We have relied on the memories of musicians, but also, we know that memories, like people, are fallible. We did the best we could to bring in an honest story.

Although The Beatles are important to the story, and the former Beatles all make appearances, this is very much a book about Wings. There are thousands of books about The Beatles for any reader curious to know more about their story. Some of the quotes have been lightly edited for style or clarity.

Ted Widmer New York February 2025

Editor’s Introduction

CLIVE ARROWSMITH: Photographer

GEOFF BRITTON: Drummer, Wings band member between 1974 and 1975

HOWIE CASEY: Saxophonist, member of Wings’ touring horn section

TONY CLARK: Sound engineer

JAMES COBURN: Actor

JOHN CONTEH: Boxer

RAY COOPER: Percussionist

TONY DORSEY: Trombonist and arranger, member of Wings’ touring horn section

LAURA EASTMAN: Sister of Linda McCartney (née Eastman)

Cast in alphabetical order xxi

GEOFF EMERICK: Sound engineer

JOE ENGLISH: Drummer, Wings band member between 1975 and 1977

BEN FONG-TORRES: Journalist, Rolling Stone

JOHN HAMMEL: Road manager for Wings

GEORGE HARRISON: Musician, former member of The Beatles

RICHARD HEWSON: Orchestral arranger

DUSTIN HOFFMAN: Actor

STEVE HOLLEY: Drummer, Wings band member between 1978 and 1981

ROGER HUGGETT: Art director

CHRISSIE HYNDE: Musician, member of The Pretenders

ERIC IDLE: Actor and comedian

MICHAEL JACKSON: Musician

MICK JAGGER: Musician, member of The Rolling Stones

GLYN JOHNS: Sound engineer and record producer

TREVOR JONES: Wings roadie

LAURENCE JUBER: Guitarist, Wings band member between 1978 and 1981

xxii Cast in alphabetical order

PAMELA KEATS: Wardrobe designer for Wings

EDDIE KLEIN: Sound engineer

DENNY LAINE: Musician, founding member of Wings and band member between 1971 and 1981

JOHN LECKIE: Sound engineer and producer

JOHN LENNON: Musician, former member of The Beatles and The Plastic Ono Band, husband of Yoko Ono

DAVID LITCHFIELD: Designer, graphic artist and filmmaker

KENNY LYNCH: Entertainer and actor

GEORGE MARTIN: Record producer

LINDA M cCARTNEY ( NÉE EASTMAN): Photographer and musician, wife of Paul McCartney, founding member of Wings, and band member between 1971 and 1981

MARY M c CARTNEY: Photographer and director, daughter of Paul and Linda McCartney

MICHAEL M c CARTNEY: Singer and photographer, brother of Paul McCartney

PAUL M c CARTNEY: Musician, former member of The Beatles, husband of Linda McCartney, founding member of Wings, and band member between 1971 and 1981

STELLA M c CARTNEY: Fashion designer, daughter of Paul and Linda McCartney

JIMMY M cCULLOCH: Guitarist, Wings band member between 1973 and 1977

Cast in alphabetical order xxiii

HENRY M cCULLOUGH: Guitarist, Wings band member between 1972 and 1973

YOKO ONO: Multimedia artist and musician, co-founder of The Plastic Ono Band, wife of John Lennon

SEAN ONO LENNON: Musician, son of John Lennon and Yoko Ono

ALAN PARSONS: Sound engineer, producer and musician

AUBREY ‘PO’ POWELL: Graphic designer, co-founder of Hipgnosis design firm

TOM SALTER: Promoter and tour manager

DENNY SEIWELL: Drummer, founding member of Wings, and band member between 1971 and 1973

DAVID SPINOZZA: Session guitarist

RINGO STARR: Drummer, former member of The Beatles

DEREK TAYLOR: Publicist for The Beatles

CHRIS THOMAS: Record producer

ALLEN TOUSSAINT: Musician and record producer, owner of Sea-Saint Studio, New Orleans

TWIGGY: Model, actress and singer

TONY VISCONTI: Musician, arranger and record producer

KLAUS VOORMANN: Artist and musician, early friend of The Beatles from Hamburg

xxiv Cast in alphabetical order

EIRIK ‘THE NORWEGIAN’ WANGBERG: Sound engineer

CHRIS WELCH: Journalist, Melody Maker

JANN WENNER: Founder and editor of Rolling Stone

TONY WILSON: Musician, leader of the Campbeltown Pipe Band

ERNIE WINFREY: Sound engineer

Cast in alphabetical order xxv

In my end is my beginning.

–T. S. Eliot, from ‘East Coker’, Four Quartets

AS THE TUMULTUOUS 1960S came to a close, The Beatles, the band that had done so much to define the decade, were on the verge of breaking up. Ironically, they were also at the peak of their powers, recording two albums in 1969, including Abbey Road, arguably the summit of their achievement. Appropriately for a summit, the album was nearly called Everest, after a brand of cigarette favoured by engineer Geoff Emerick.

But the mountain held crevices. In various ways, The Beatles were drifting apart, pulled by new interests and new relationships. Still, they kept trying to come together, as the opening track on Abbey

Road promised, along with other songs about love and sunshine. But each effort to climb the mountain brought new strains, especially for the band member who had assumed most of the responsibility for organising these expeditions.

Around the world that autumn, a ludicrous rumour spread that ‘Paul is dead’, thanks to overzealous fans reading too much into lyrics and a mysterious licence plate – 281F, supposedly alluding to Paul’s age if he was still alive – in the background of the Abbey Road cover photo. But in a sense, the rumour hinted at a larger, metaphorical truth, as The Beatles, and their fans around the world, sensed that something important was ending.

As always, Paul took a sad song and made it better. It would be hard to improve upon ‘The End’, the penultimate track on Abbey Road, with its last couplet and its philosophy of uplift: ‘The love you take is equal to the love you make.’

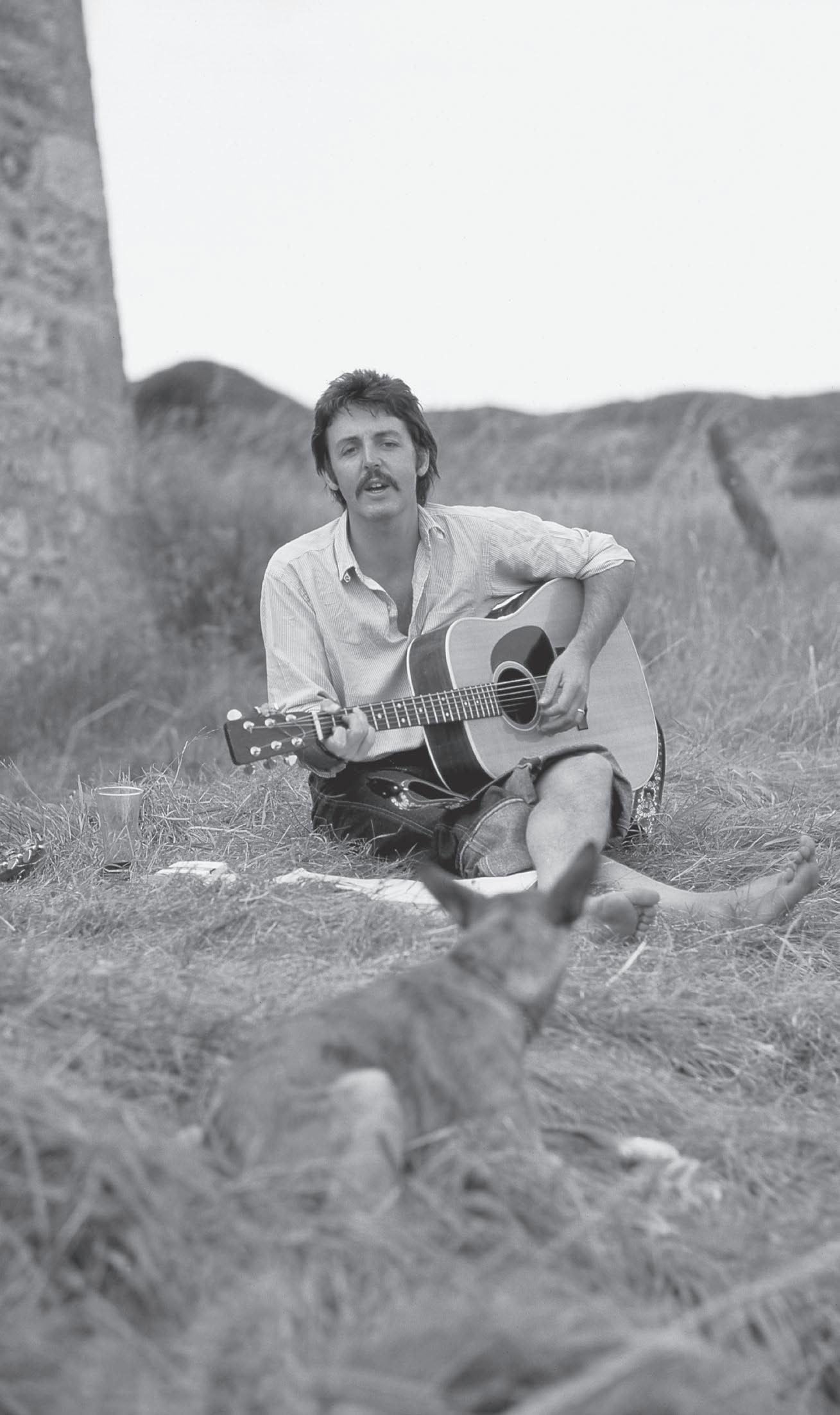

Scotland, 1969

In the end, he accepted that guidance for himself as well. After a hard fall, he began to work on a new album, quite different from The Beatles, brimming with the love he had found inside his new family and his amazement at life’s regenerative quality. Everything that would come after – the story of Wings – would follow from this new beginning.

Even as they neared the end, it was clear that The Beatles had achieved something timeless, far beyond the imagination of the teenagers who had started playing together under a strange name, riffing on Buddy Holly’s Crickets, as the sixties were beginning.

PAUL M c CARTNEY: Making music. The way that my generation, or my gang, did it was making it up ourselves. Hardly anyone I knew could read or write music. But we could do ‘A Day in the Life’.

JOHN LENNON: We were all on this ship in the sixties, our generation, a ship going to discover the New World. And The Beatles were in the crow’s nest of that ship.

GEORGE HARRISON: We did pretty good considering we were just four Liverpool lads.

RINGO STARR: We were honest with each other and we were honest about the music. The music was positive. It was positive in love. They did write – we all wrote – about other things, but the basic Beatles message was Love.

QUEEN ELIZABETH II [speech on her fiftieth wedding anniversary, 1997]: What a remarkable fifty years they have been: for the world, for the Commonwealth and for Britain. Think what we would have missed if we had never heard The Beatles.

LEMMY KILMISTER [bassist, Motörhead]: I saw The Beatles play The Cavern in Liverpool when I was sixteen. They had attitude: Onstage, they were like a four-headed monster.

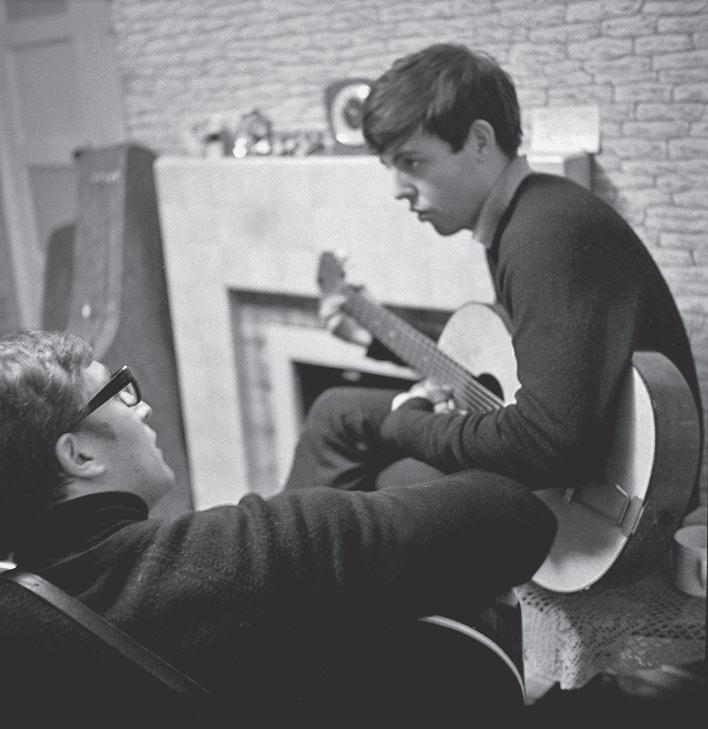

John Lennon and Paul McCartney. Forthlin Road, Liverpool, 1962

ALLEN GINSBERG [in 1965]: Liverpool is at the present moment the centre of the consciousness of the human universe.

MICHAEL M c CARTNEY: It was a unique, never-to-be-repeated experience.

Because you’ve got to remember that we were just two little Liverpool lads in a two-up, two-down terraced house, going nowhere. Then Mum died, and Dad bought me a banjo and my brother a guitar, and then a set of drums fell off the back of a lorry, as we say in Liverpool. And music was introduced into the house. Whereas if Mum had been alive, we’d have had to get on with our studies and get to university and get a decent job. So there it is. Just lads. Our Kid [Paul] in one room, me in the other, learning photography. My brother in the other room learning music. That was a fascinating reality of a Scouse house, hearing songs being formed. It’s wonderful how God works in mysterious ways.

SEAN ONO LENNON: It went beyond just two people who were best friends, or had a nice friendship or something. It feels like, looking back, that their relationship was so vital that it didn’t

even matter if they did want to be friends. It seemed like they had to work together. There was some kind of force or magnetism, they needed each other, and it was inevitable. They couldn’t avoid each other, even when they wanted to, during later periods in The Beatles. They complemented each other like a plus and minus on a magnet. There was an artistic, intellectual connection that transcended mere mortal friendships, or even brotherhood and family relationships. It was something beyond that.

STEVE JOBS [ founder of Apple Inc.] : My model for business is The Beatles. They were four guys that kept each others’ negative tendencies in check; they balanced each other. And the total was greater than the sum of the parts.

MICHAEL M c CARTNEY: We were simply going nowhere. We lived up north in a place called Liverpool. The country was divided by the class system, and the money and the power lived in London. Anything north of Watford was hinterland. It was jungle. It didn’t exist. So it’s only when Our Kid kept practising, got Johnny to come round, then George, and then Ritchie [Ringo]. They went down to London and took over London, then Europe, then America, and then the world. When we started out, there was no chance, no hope for us. So you think of the resilience in them. That was such a powerful explosion of the world’s consciousness.

SEAN ONO LENNON: It was something that feels almost not of this world. I don’t even know if I believe in the supernatural, but let’s put it this way: When we look at the relationship of John Lennon and Paul McCartney, it’s an argument for the cosmic. It’s an argument for fate. It’s an argument for some kind of divine order, because it’s just hard to believe that it just happened by accident that they all met. And it’s not just the two of them, but the four of them. There’s a chemistry to that, for some, that feels like there was some kind of divine hand that intervened.

TIMOTHY LEARY [ psychologist and advocate of psychedelic drugs] : I declare that The Beatles are mutants. Prototypes of evolutionary agents sent by God, with a mysterious power to create a new species - a young race of laughing freemen.

BRIAN WILSON [ The Beach Boys] : We were, of course, very jealous of The Beatles.

SEAN ONO LENNON: They were pioneers in a hundred ways that weren’t even just the music. It’s really hard to explain to young music fans who are getting into The Beatles on their Spotify playlist. It’s hard to explain to them how singular The Beatles phenomenon was.

LEONARD BERNSTEIN [ conductor and composer ] : [Lennon and McCartney] made a pair embodying a creativity mostly unmatched during that fateful decade. Ringo – a lovely performer. George – a mystical, unrealised talent. But John and Paul, Saints John and Paul, were, and made and aureoled and beatified and eternalised the concept that shall always be known, remembered and deeply loved as The Beatles. And yet the two were merely something – the four were It.

SEAN ONO LENNON: I’ve heard Quincy Jones say that you always have to leave room for God to walk through the room. Meaning you can’t try to control every bit of the creative process. That’s why The Beatles’ music feels so magical. Because the four of their relationships, but especially Paul and my dad’s relationship, pushed them beyond themselves. Beyond their limitations as individuals. What makes the music so special is the sound of people being pushed beyond themselves and beyond their basic abilities. I think that’s what they gave each other.

MICK JAGGER: They were always bigger than life. They were so all-encompassing and huge. It was a complete craze. We haven’t seen anything like it since.

2 JAN The Beatles begin a combined concert and TV project at Twickenham Film Studios, eventually to result in the film Let It Be and the documentary Get Back

13 JAN The Beatles release Yellow Submarine

13 JAN Elvis Presley begins a series of recording sessions at American Studios in Memphis that will yield latecareer hits, including ‘In the Ghetto’, ‘Suspicious Minds’ and ‘Kentucky Rain’

21 JAN Richard Nixon is sworn in as the thirty-seventh president of the United States

21 JAN Apple release Post Card by Mary Hopkin. The album is produced by Paul McCartney

22 JAN The Beatles’ sessions move from Twickenham to the basement of the Apple offices at 3 Savile Row

30 JAN The Beatles perform on the roof of Apple offices

17 FEB Apple release the eponymous debut album by James Taylor, featuring Paul playing bass on ‘Carolina in My Mind’

2 MAR John Lennon performs with Yoko Ono in an improvisatory concert at Lady Mitchell Hall, Cambridge University

12 MAR Paul McCartney marries Linda Eastman at Marylebone Registry Office in London; on the same day, police raid the Esher home of George and Pattie Harrison

18 MAR Operation Breakfast, the secret bombing of Cambodia, begins

20 MAR John Lennon marries Yoko Ono at the British Consulate Office in Gibraltar

25–31 MAR John Lennon and Yoko Ono host a ‘Bed-In’ in the presidential suite of the Amsterdam Hilton, to protest for peace

28 MAR Mary Hopkin releases the single ‘Goodbye’ written by Paul McCartney. It reaches number 2 in the UK singles chart, held off the top spot by ‘Get Back’ by The Beatles

11 APR The Beatles release ‘Get Back’

14 APR John Lennon and Paul McCartney record ‘The Ballad of John and Yoko’

22 APR John changes his name from John Winston Lennon to John Ono Lennon

30 APR The number of US troops in Vietnam reaches its peak –543,482

9 MAY John Lennon and Yoko Ono release Unfinished Music No. 2: Life With the Lions

9 MAY George Harrison releases Electronic Sound

26 MAY John Lennon and Yoko Ono begin an eight-day ‘Bed-In’ for peace in suite 1742 of the Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montreal

30 MAY The Beatles release ‘The Ballad of John and Yoko’

1 JUN John Lennon and Yoko Ono record ‘Give Peace a Chance’ inside their crowded hotel room in Montreal

2 JUN Elvis Presley releases From Elvis in Memphis

22 JUN The Cuyahoga River, covered with oil slicks, catches fire in Cleveland, helping to increase environmental awareness

28 JUN After New York police attempt to arrest several patrons at the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, a crowd of gay activists push back against the police and force a tense stand-off, now considered the beginning of the Gay Pride movement

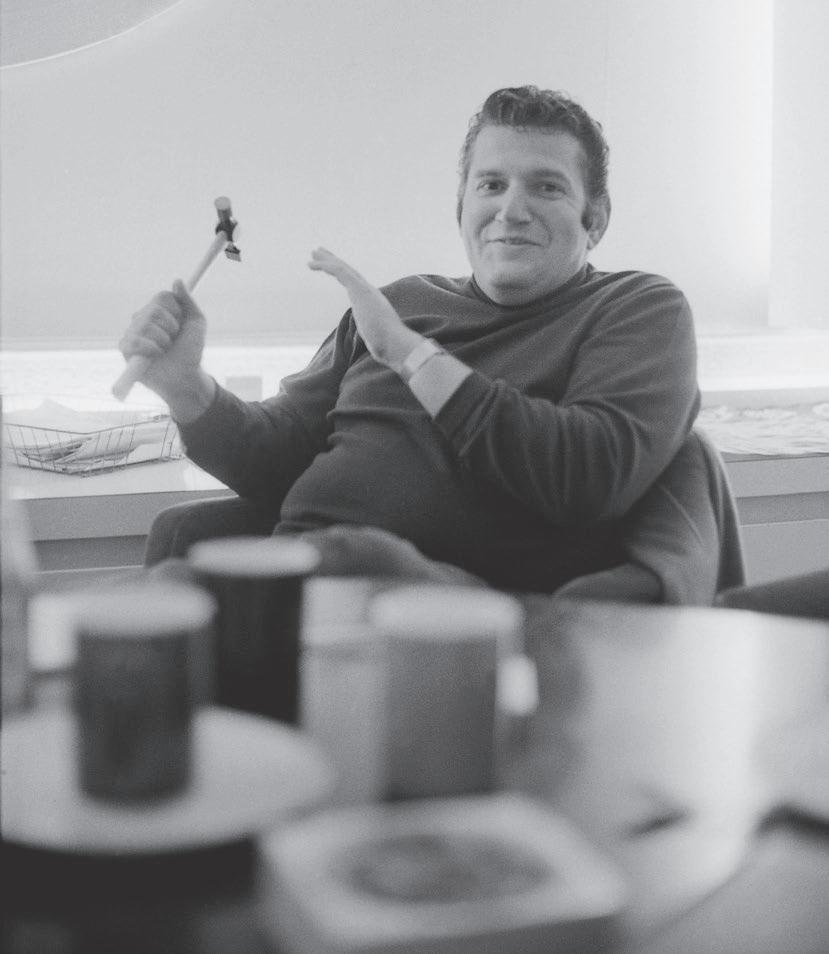

Allen Klein at Apple Corps. Savile Row, London, 1969

In Ernest Hemingway’s 1926 novel The Sun Also Rises, a character is asked how he went bankrupt, and he answers, ‘Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.’

That might describe the way in which The Beatles finally reached the end. Bankruptcy had something to do with it, as they realised just how much money they were losing through their quixotic business ventures.

That eventually led three of The Beatles to hire a former accountant, Allen Klein, over Paul’s objections. Klein, an abrasive New Yorker, had made a reputation for securing better deals for his clients, who included Bobby Darin, Sam Cooke and The Rolling Stones. But he also was known to feather his own nest.

Throughout 1969 a series of difficult legal and financial negotiations widened the divide between The Beatles. Although they kept making extraordinary music, the strain was palpable. George wrote song after song about his misery, including ‘I Me Mine’ and ‘All Things Must Pass’, which suggested that he was more than ready for a solo career. Paul was also finding solace in writing quiet songs, away from the noise.

KLAUS VOORMANN: It was impossible. They were really professional. If you think of the last LPs – like Abbey Road, it’s a great record, it’s very professional, it has great songs, it’s well played, but the band didn’t exist anymore.

John said, ‘Klaus, I want to put a band together, called the Plastic Ono Band. Do you want to play the bass?’ I didn’t know Yoko and I had no idea what they were going to do. Were they going to be in underpants on stage? What were we going to do? I had no idea. Maybe no pants at all! And he said, ‘No, no, no! I want to have a band that tours and records. Eric Clapton already said yes and now I’m asking you.’ So I said, ‘Yeah, OK, let’s do it.’

PAUL M c CARTNEY: The Beatles have left The Beatles, but no one wants to be the one to say the party’s over.

JOHN LENNON: Why should The Beatles give more? Didn’t they give everything on God’s Earth for ten years? Didn’t they give themselves? Didn’t they give all?

GEORGE HARRISON: I don’t regret really anything. That’s what happened and it was good. But it was also good to carry on and do something else. In fact it was a relief. Some people can’t understand that because Beatles was such a big deal, they can’t understand why we should actually enjoy splitting up. But there’s a time when people grow up and they leave home and they go through a change. And it was really time for a change.

RINGO STARR: Yoko’s taken a lot of shit, her and Linda, but The Beatles’ breakup wasn’t their fault. It was just that suddenly we were all thirty and married and changed.

PAUL M c CARTNEY: If my dream at the time was to get back to where we once belonged, John’s dream was to go beyond where we once belonged, to go somewhere we didn’t yet belong.

DEREK TAYLOR: Apple was an insane place then.

LINDA M c CARTNEY: It was weird times. Allen Klein was stirring it up something awful. They had John so spinning about Paul it was really quite heartbreaking. It reminded me of the Eisenstein movie Ivan the Terrible; they were all whispering.

PAUL M c CARTNEY: You can’t blame John for falling in love with Yoko any more than you can blame me for falling in love with Linda. We tried writing together a few more times, but I think we both decided it would be easier to work separately.

I told John on the phone that at the beginning of last year [1969] I was annoyed with him. I was jealous because of Yoko, and afraid about the breakup of a great musical partnership. It’s taken me a year to realise that they were in love. Just like Linda and me.

There’s so much happening during that time. Here’s my

diary. September 1969. I was only twenty-seven. ‘This is the day that John said, “I want a divorce.” ’ The day The Beatles broke up. We decided to keep it a secret. I just remember thinking to myself, ‘Oh, fuck!’

SEAN ONO LENNON: It’s because we love the music so much that we’re so obsessed. It’s like when you’re obsessed with The Lord of the Rings and you start to wonder, ‘What was Frodo feeling at this moment?’ People just obsess about, was Paul really the better songwriter? Was Dad really the more experimental one? But that stuff is just silly and meaningless, ultimately. Because together they made the greatest music of their generation.

CHRIS WELCH: It’s a tragedy, really, that they broke up when they did. Because I think if they’d carried on, they would have had better management, better PA systems, and they could have done incredible shows. The Beatles at Glastonbury would have been amazing. But their time had come. They had to go.

1 JUL The Investiture of Prince Charles as Prince of Wales is held in Caernarfon Castle in Wales

1 JUL John Lennon and Yoko Ono, travelling with John’s son Julian and Yoko’s daughter Kyoko, are involved in a car crash in Golspie, Scotland, requiring hospitalisation

3 JUL In a press release, Stanford University announces the creation of a network of interconnected computers around the country, a forerunner to the internet

4 JUL Using the name The Plastic Ono Band, John Lennon and Yoko Ono release the first solo single by a Beatle, ‘Give Peace a Chance’

5 JUL The Rolling Stones play a free concert at Hyde Park, London, and pay a tribute to founding member Brian Jones, who had died two days earlier. Paul McCartney is in attendance

16 JUL Apollo 11 lifts off from Cape Kennedy for the moon

21 JUL Neil Armstrong becomes the first human to walk on the lunar surface. Paul and Linda McCartney watch from their bed in London where the local time is 2:56 a.m

31 JUL Elvis Presley returns to performing concerts for the first time since 1961, in Las Vegas

8 AUG At 11.35 a.m., with a policeman holding up traffic, The Beatles are photographed by Iain MacMillan walking over the zebra crossing at Abbey Road

15 AUG The Woodstock Festival begins at Max Yasgur’s farm near Bethel, New York, lasting until the morning of 18 Aug

20 AUG All four Beatles attend a session at EMI Studios, Abbey Road, for the final time

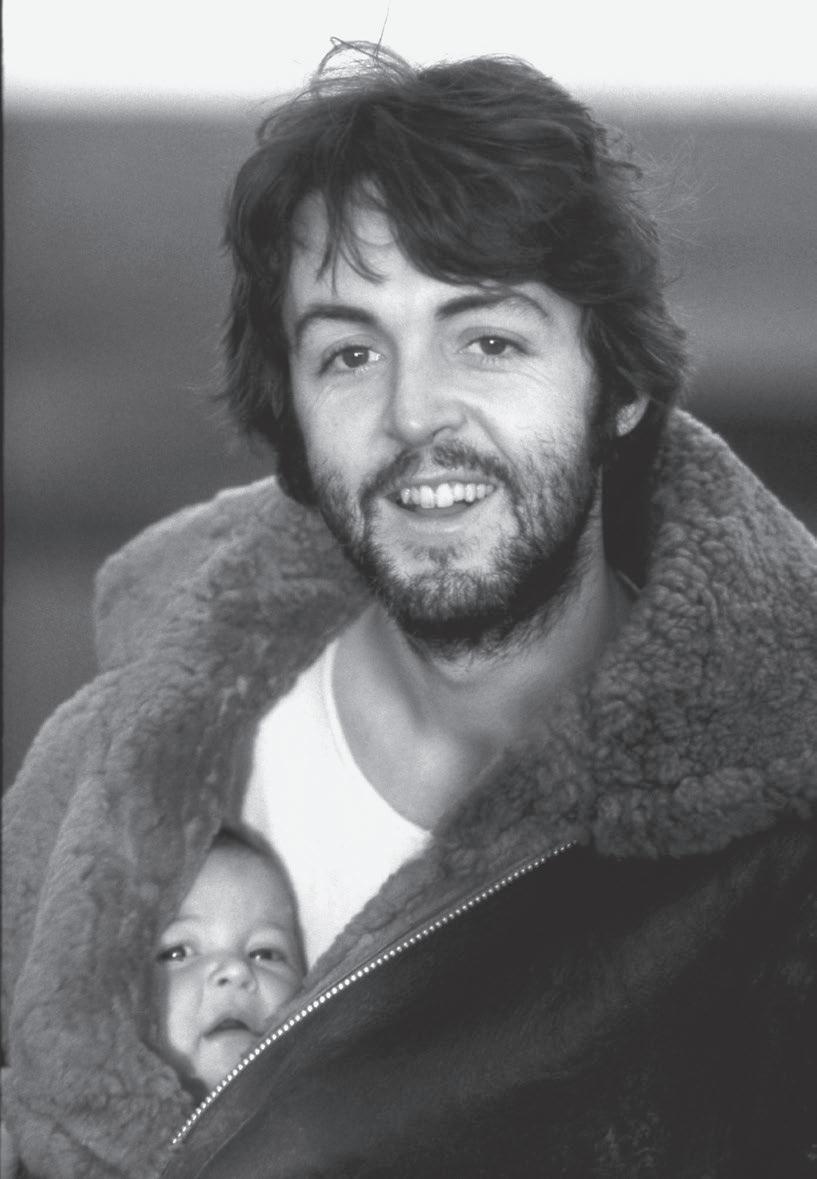

28 AUG Mary McCartney is born to Paul and Linda McCartney at Avenue Clinic, St John’s Wood, London

13 SEP John Lennon performs with The Plastic Ono Band at the Toronto Rock and Roll Revival

22 SEP John Lennon tells The Beatles he wants a ‘divorce’

26 SEP The Beatles release Abbey Road

5 OCT Monty Python’s Flying Circus premieres on the BBC

6 OCT The Beatles release ‘Something’/‘Come Together’

20 OCT The Plastic Ono Band release ‘Cold Turkey’/‘Don’t Worry Kyoko (Mummy’s Only Looking for a Hand in the Snow)’

20 OCT John Lennon and Yoko Ono release Wedding Album

1 NOV Paul and Linda McCartney are surprised at High Park Farm by a reporter, Dorothy Bacon, and a photographer, Terence Spencer, from Life magazine

7 NOV In the wake of the ‘Paul is dead’ rumours, Life features Paul McCartney, very much alive, on its cover

25 NOV John Lennon returns his MBE medal to the Queen, in protest against ‘Britain’s involvement in the Nigeria–Biafra thing, against our support of America in Vietnam, and against “Cold Turkey” slipping down the charts’

28 NOV The Rolling Stones release Let It Bleed

AUTUMN/ WINTER Paul McCartney begins recording at home for what would become his debut solo album, McCartney

6 DEC The Rolling Stones host a free concert at Altamont Speedway in California, attracting 300,000 people, but the event is marred by the death of four concertgoers

12 DEC John Lennon and The Plastic Ono Band release Live Peace in Toronto 1969

17 DEC In a speech to the American Geophysical Union, a scientist, Joseph O. Fletcher, warns that the Earth’s climate is warming because of human activity

UK The Best of the Seekers – The Seekers; The Sound of Music – Original Soundtrack Recording; His Orchestra, His Chorus, His Singers, His Sound – Ray Conniff; Abbey Road – The Beatles; At San Quentin – Johnny Cash; Oliver! – Original Soundtrack Recording; According to My Heart – Jim Reeves; Post Card – Mary Hopkin; Nashville Skyline – Bob Dylan; Diana Ross and The Supremes Join The Temptations – Diana Ross and The Supremes and The Temptations

US In-a-Gadda-Da-Vida – Iron Butterfly; Hair – Original Broadway Cast Recording; Blood, Sweat and Tears –Blood, Sweat and Tears; Bayou Country – Creedence Clearwater Revival; Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin; At San Quentin – Johnny Cash; Funny Girl – Original Soundtrack Recording Barbra Streisand; The Beatles –The Beatles; Donovan’s Greatest Hits – Donovan; And Then . . . Along Comes The Association – The Association

As painful as the business meetings were, and the feeling that he was outnumbered and outvoted on every issue by the other three Beatles, Paul was hardly alone. In important ways, he had never been less alone.

Linda Eastman had grown up in Scarsdale, outside New York City, in a home full of art and music. Her father, a lawyer, represented everyone from abstract expressionists to Broadway tunesmiths. One of them, a writer of show tunes named Jack Lawrence, wrote a song for his lawyer’s daughter when she was only a year old. ‘Linda’, recorded by Ray Noble and His Orchestra with Buddy Clark, went to number one on the Billboard charts in 1947.

But big band tunes were never going to be enough for Linda, and when rock and roll hit, she was an early convert. As the sixties progressed, she discovered photography, an art form of its own, which also gave her entrée into the concerts that she loved (including by The Jimi Hendrix Experience).

During a trip to London in May 1967, she met Paul, the last unmarried Beatle. Despite an ocean between them, their relationship grew more serious. Like Paul, she had lost her mother at a young age (in a plane crash). Their love of early rock and roll was another connection, and she could sing, hitting a difficult high note during the recording of ‘Let It Be’. That song, like so many, radiated a love of family. Linda, accompanied by six-year-old daughter Heather (by a previous marriage), moved to London, where she married Paul on 12 March 1969.

HEATHER M c CARTNEY: Linda was the most beautiful mum in the whole world.

PAUL M c CARTNEY: I’d got married to Linda, and our relationship offered some respite from the dreary infighting and the financial stuff. The lines ‘One sweet dream/Pick up the bags and get in the limousine’ [from ‘You Never Give Me Your Money’] were a reference to how Linda and I were still able to disappear for a weekend in the country. That saved me.

LAURA EASTMAN: My father, Lee Eastman, was a person who really loved culture. So, he would be listening to his classical music, and Linda’s bedroom was next to my parents’ bedroom. At a certain point, Elvis Presley came on the scene. And I remember this talk – ‘Oh, that’ll never last!’ Well, Linda got a little transistor radio. She would listen to the radio with her head under the pillow so she wouldn’t get in trouble with my parents. She just loved this new music, rock and roll. My father also represented [Jerry] Leiber and [Mike] Stoller, great Broadway writers,

Linda and Heather Eastman. Arizona, 1965

but they also wrote many great rock and roll songs eventually [including ‘Hound Dog’ and ‘Jailhouse Rock’, huge hits for Elvis Presley, and ‘Kansas City’, a hit for Little Richard, later covered by The Beatles].

In Linda’s apartment, which I eventually moved into when she and Paul went back to England, she had a collection of records. It showed her whole history of loving rock and roll. This huge collection of LPs.

MARY M c CARTNEY: She used to sneak out of her back window to go to the Apollo [the famous theatre in Harlem] to watch concerts.

LINDA M c CARTNEY: There’s a music tower where I went to high school, with a piano. I had two friends, we used to cut classes and go there, it was great. It was like being in an attic. We used to meet up there and sing ‘Blue Moon’ and things like that.

PAUL M c CARTNEY: Later, when I got to know [Paul Simon], I found out he and Linda were massive fans of doo-wop, because of the richness of it in New York. She and Paul, you couldn’t stop them. They would just be talking about The Penguins, obscure DJs, obscure stations. That’s what had set their lives afire.

LAURA EASTMAN: Linda went to the University of Arizona. She took a photography course. And then eventually she came back to New York and she got a job as the receptionist at the Town and Country magazine. And across her desk one day comes this invitation to go to a reception for The Rolling Stones, and it was on a boat on the river beside Manhattan. So she nicks it. She takes her camera, she goes, she takes photos and she sells them to the magazine, and that started her photography career with these rock and roll people. She liked to do photo sessions with these rockers in Central Park. One day, my father was walking down. She’s walking with this rocker with all this hair and a cape. He freaked out.

MARY M c CARTNEY: I spoke with Eddie Kramer, who was the engineer at Electric Lady [studio in New York]. He worked a lot with Jimi Hendrix, and he said, ‘Jimi wanted your mum in the studio.’ A lot of times they’d say, ‘Look, we don’t want these people in when we’re recording.’ But Mum was always someone that he welcomed, because he just loved having her around, and he loved her sensibility and the way she would take photographs, didn’t get in the way. I think also they inspired each other. She really had that about her.

CHRISSIE HYNDE: She was fun. She wasn’t at all pretentious. She was not at all a snob. She wasn’t a star fucker. She loved rock. She loved taking pictures. She loved pretty much all my heroes, and probably had photographed them all. Neil Young, Jimi Hendrix, obviously The Beatles. She didn’t like being in the limelight. She was the perfect person if you wanted to get away from all

that. And she could cook. She liked ordinary things. I can still remember seeing pictures of them in the studio, and there’d be a box of PG Tips. And you’d think, ‘Wow, they could get any kind of tea they want, but they’re getting the ordinary stuff from the supermarket.’

STELLA M c CARTNEY: All I know is that it was real and that it was raw, and it was something that lasted and would’ve lasted the length of a lifetime, had the course of history allowed it. He saw a jewel in the crowd. There would have been a mutual attraction, and a mutual respect, and a mutual true seeing of who that person is. From an informed point of view. From a place where they were ready.

MARY M c CARTNEY: She was just a complete individual. She’d wear odd socks. She loved cooking, and she loved bringing together people through food. That would often be American recipes, making brownies or things like that. This feeling of America back then, it was this feeling of anything is possible. Whereas us Brits can be a bit pessimistic. I think her attitude was ‘Why not?’ Similar to Dad. In my family, it’s like, ‘Please don’t tell any of us that you’re not allowed to do something, because then you’ll just see everybody’s eyes spark up and go, “That’s exactly what I want to do now.” ’

SEAN ONO LENNON: What distinguishes The Beatles from other bands, what generally makes them remarkable, is not just the music. It’s also that they were cultural leaders. They were on the leading edge of thought and politics and art and feminism and social justice, or whatever they call it now. They weren’t just rock stars who wanted to have a trophy wife, which they could have been. A lot of people are happy that way. But they were feminists, and they were on the edge of the evolution of what it meant to be successful men in the world. It’s interesting. It’s more than interesting. It reflects who they were

as people. They weren’t just your average narcissistic, selfindulgent rock star who wanted arm candy. They were deep thinkers. And I think that is another reason that their music is in its own class.

PAUL M c CARTNEY: One of the things about Linda, when you talk about how people seem at ease in her photos, is that it was her lifestyle. We’d say: ‘Let’s go out of London,’ so I’d just drive, we’d get out of London and I’d say: ‘Where do you want to go?’ She’d say: ‘Just anywhere.’ After a while, you’d end up in areas you didn’t know, going: ‘Ooh, I’m getting a bit lost here,’ and she’d say: ‘Great.’ You were in places you’d never been, you were seeing things you hadn’t intended to see, all of which was rich stuff for her photography. I remember I wrote the song ‘Two of Us’ about that – ‘Two of us riding nowhere - Spending someone’s hard-earned pay.’ That was one of those excursions, when we were first going out together, this great idea of getting lost. Until I met Linda, I panicked when I got lost.

‘Nowhere’ quickly turned into Somewhere. Specifically, Scotland, where Paul had bought a rural hideaway in 1966, on the advice of financial advisors. High Park Farm was a 183-acre sheep farm on the Kintyre Peninsula, in Argyllshire. Though it had belonged to the dukes of Argyll for centuries, it was in a dilapidated state, and difficult to reach, along roads that gave new meaning to the phrase ‘long and winding’. In other words, it was the perfect place for someone who wanted to hide away from the world.

In the autumn of 1969, Paul and Linda came here with their daughters Heather and Mary and settled in. It was a bleak time of year, but that may have added to the appeal, as Paul wrestled with depression. Shakespeare set Macbeth in Scotland because it offered a properly desolate setting. For a singer thought to be deceased, it might have felt like the right place to confront his mortality. ‘The dead man’s knell is there,’ Shakespeare wrote.

Campbeltown, Scotland, 1968

PAUL M c CARTNEY: Someone from the office rang me up and said, ‘Look, Paul, you’re dead.’ I said, ‘I don’t agree with you.’ And they said, ‘Look, what are you going to do about it? It’s a big thing breaking in America. You’re dead.’ So I said, ‘Leave it, just let them say it. It’ll probably be the best publicity we’ve ever had, and I won’t have to do a thing except stay alive.’ I managed to stay alive through it.

They fixed up the house and lived simply. Still, they were not entirely alone. One day, their privacy was breached by a writer and a photographer from Life magazine, wondering if Paul was still among the living. At first he was annoyed at the intrusion and was photographed throwing a bucket of slop at his unwelcomed visitors. But then he realised it was better to give a thoughtful interview, even shaving for the photos. To settle the question, Paul explained his perspective on The Beatles and their impending demise. Remarkably, no one noticed when he admitted, ‘The Beatles thing is over.’ But

Heather, Mary and Paul McCartney in Scotland. 1969

it was there in plain sight, when the interview was published, with Paul and his family on the cover. It would be a different story in a few months’ time.

Over time, Paul’s depression receded. Linda’s love never faltered, and something about Scotland healed him. There was no shortage of work on a farm, and there were few helpers to do it for him. Everything from sheep shearing to furniture building turned into a form of therapy. He was also hearing his muse again. When the family returned to London, he was working on a new song, about the love that had sustained him during his hour of darkness. From that song, others would follow, celebrating a newfound freedom.

PAUL M c CARTNEY: Leaving The Beatles, or having The Beatles leave me, whichever way you look at it, was very difficult because that was my life’s job. So, when it stopped, it was like, ‘Oh God, what do we do now?’ In truth, I didn’t have any idea. There were two options: either don’t do music and think of something else, or do music and figure out how you’re going to do that.

LINDA M c CARTNEY: I remember Paul saying, ‘Help me take some of this weight off my back,’ And I said, ‘Weight? What weight? You guys are the princes of the world. You’re The Beatles.’ But in truth Paul was not in great shape; he was drinking a lot, playing a lot and, while surrounded by women and fans, not very happy. We all thought, ‘Oh, The Beatles and flower power’ - but those guys had every parasite and vulture on their backs.

PAUL M c CARTNEY: I remember lying awake at night, shaking, which has not happened to me since. One night, I’d been asleep and awoke and I couldn’t lift my head off the pillow. My head was down in the pillow; I thought, ‘Jesus, if I don’t do this, I’ll suffocate.’ I remember hardly having the energy to pull myself up, but with a great struggle I pulled my head and lay on my back and thought, ‘That was a bit near!’

LINDA M c CARTNEY: Scotland was like nothing I’d ever lived in. It was the most beautiful land you have ever seen; it was way at the end of nowhere. To me, it was the first feeling I’d ever had of civilisation dropped away. I felt like it was in another era. It was so beautiful up there, clean, so different to all the hotels and limousines and the music business, so it was quite a relief, but it was very derelict.

PAUL M c CARTNEY: I went up there before I met Linda, and I didn’t really like it. I’d expected Scotland to be forests and mountains, and this was hills and virtually no trees. It was underwhelming. I met my neighbour there, an old guy named Ian McDougall. Ian was a real Highlander, you could barely understand what he was talking about. I worked out that I might try to catch the last word in the sentence. So he’d say something, and I’d hear ‘sheep’, and I’d go, ‘Aye, sheep! The clipping of the sheep!’ But I was a stranger there. Then, when I met Linda, she said, ‘Have you got a farm in Scotland? Can we go there?’ We went, and suddenly I saw it through her eyes. And she loved it. Going up to Scotland was real freedom for us. It was an

escape, our means of finding a new direction in life and having time to think about what we really wanted to do. It was pretty heavy down in London, and we were thinking, ‘Oh God, what’re we going to do?’ And then it was like, ‘Let’s escape.’

STELLA M c CARTNEY: When COVID came and everyone went into isolation, I’m like, ‘This doesn’t feel weird to me.’ My parents chose isolation. That was a choice that they made to get as far away from reality as possible. And they achieved it. The driveway coming off the road to the farm, I don’t even know how many miles long that is, but it’s pretty isolated. We had a standing stone [an ancient monolith] outside the kitchen window, for crying out loud. What? Like, that shit doesn’t happen, does it? It’s not normal.

MARY M c CARTNEY: I think they ran away, basically.

PAUL M c CARTNEY: When they ring up to say, ‘You’ve got a meeting on Thursday’ . . . ‘Sorry! We’re in Scotland!’

MARY M c CARTNEY: They just closed ranks. They were like, ‘We love each other.’ The only way to get through this is to get away from London, be really funky and just do the opposite of city life. Back to basics. Shearing sheep, picking potatoes, horse riding in the middle of nowhere, going to the beach with your kids, just being together. Sing, create music in your back room.

PAUL M c CARTNEY: We’d been plonked into this new life and we just had to figure it out.

STELLA M c CARTNEY: That American spirit that Mum had. Americans are a bit more positive, a bit more like ‘Come on, chirp up.’

PAUL M c CARTNEY: But all along, the person that didn’t go that way was Linda. She’s just that kind of woman, who could help me through that. Gradually we got it together.

Every year, the office had bought my Christmas tree. I remember thinking, ‘I’m going to go out and buy it myself.’ With The Beatles, it had all been done for me. Once you realise that’s the way you’re living, you suddenly think, ‘Yes, come on! Come on, life, come on, nature!’

STELLA M c CARTNEY: When I became a teenager, I hated going there. I was like, ‘Oh my God. This loch. This rock. Can I please just get to the Hamptons?’ And now, honestly, they’re the best memories for all of us, that really unify and bring us all to the same place. Our family is so respectful to nature. It’s such a big part of who we are. And it was in its rawest form out there in Scotland, with the streams and the tadpoles. And you truly saw the seasons, and the flowers, and getting bucked off our horses, and having to walk through bracken. And the senses, you know?

PAUL M c CARTNEY: We put our backs into it, tilling the fields, and grew all sorts in our vegetable garden. We had some seriously good turnips. I learned some tricks from my dad and his flowers in our garden at home, so put those to good use up in Scotland. And, to this day, it never ceases to amaze me: I put a seed in the ground, the rain comes to water it, the sun comes to shine on it, then something grows and you can eat it. That’s always something we can be grateful for.

We were back to nature, and the sky there is magnificent. There wasn’t much to spend our money on, and we didn’t have a lot of it then. But we were making do, and that was great, finding solutions to things. We didn’t have a bath. But next door to our little kitchen, there was a place where the farmers had cleaned the milking machinery. It was a tub that was three foot off the ground, a big galvanised tub. I said, ‘We should fill this with hot water, we can have a bath.’ It was that kind of thing.

MARY M c CARTNEY: Mum and Dad would have the vegetable patch. Me and Stella would go down and sort of steal sweet peas and eat them there, or Mum and Dad would come with a

turnip. And I remember Dad liked peeling a bit of a turnip and saying, ‘Taste some of this. It’s the most delicious turnip you’ve ever tasted.’ And we’d roll our eyes at him, going, ‘What the heck!’ But now I’ve got to the age myself where I fully appreciate it. They went back to appreciating what you might call the simpler things in life, but I would say the more important things in life.

STELLA M c CARTNEY: Scotland influenced so much. As children, it was the most peaceful place. The five of us – as James wasn’t quite born yet – were so isolated and we got to be a close-knit family. Mary and I bonded so much at that time because we were so close in age and we would horse-ride all day and get lost in the hills, get bucked off and have to walk home.

For me, the fashion influence from that period was what was on the farm! Being on the road with Wings was rock and roll. . . . It was just all so cool – sequins, velvets, rhinestones, platform boots, culottes, prints mashed up, airbrushing, graphic T-shirts. That style was just so iconic and was the absolute contrast of Scotland, which was the being in the fields and with family, in nature, and the sounds and the smells that came with that. All of the senses were just completely on overload in Scotland because there was so much space and time around everything. You could really feel everything that was happening around you.

On tour, everything was so chaotic. You went from a tour bus to a plane to the stage to your gig to backstage to whatever else. It was constant movement.

The two contrasts have been a massive, massive influence on how I design, and can still be felt in everything I do to this day. They’re in the images that I create for my ad campaigns and in my store design, where I have rocks from Scotland. I have all the textures, the colours, the sounds and the smells. There’s so much influence from those periods and places.

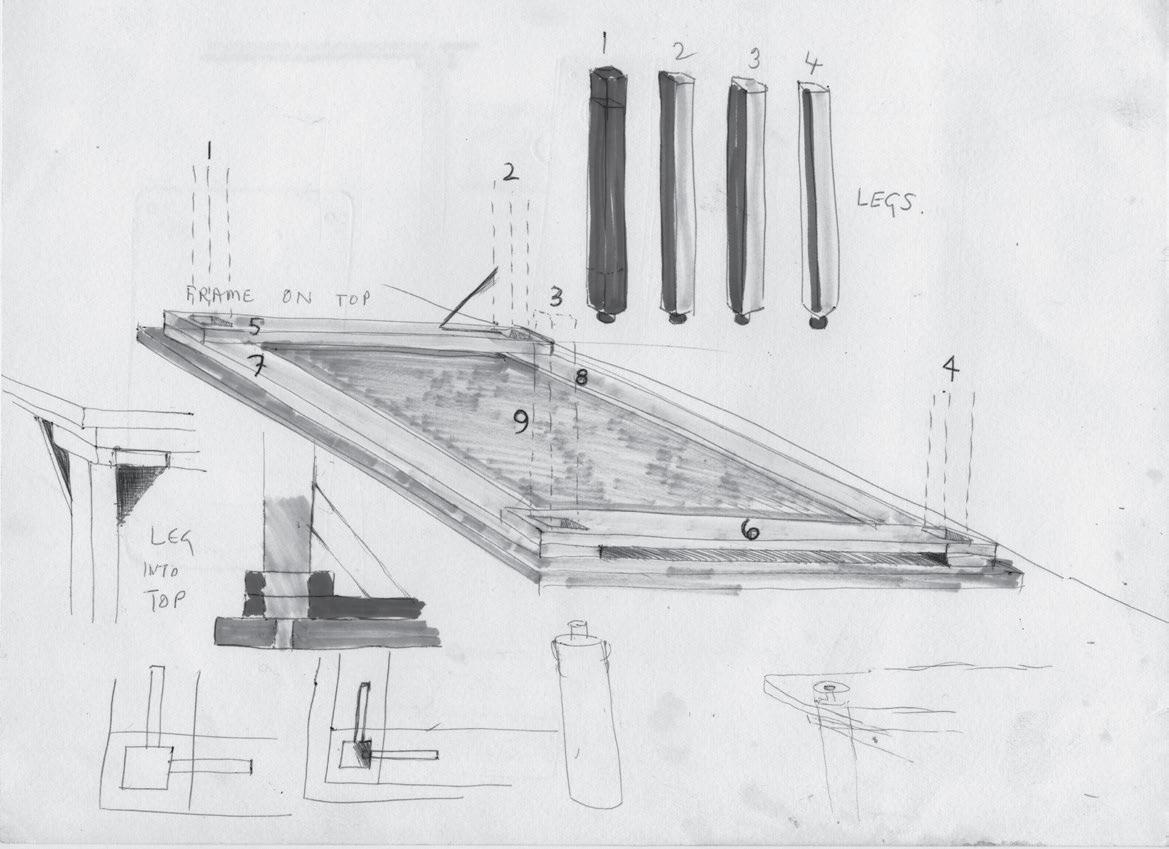

PAUL M c CARTNEY: I ended up making a table, which was so gratifying. I’d taken woodwork in school. You ask most kids from that era, and woodwork was a great favourite lesson.

I decided I was going to do it with no nails, just with glue. I drew the thing, got my little sketches of how wide it was to be and how the legs were going to fit in. When I’d been in school, at the Liverpool Institute, we had woodwork classes, which a lot of us guys liked. I remembered a couple things, how to make a dovetail joint. I thought, ‘I know how to do that.’ Over the next couple of months, I went into town and got myself a chisel and a hammer. So, I had the whole structure, but it was still planks of wood, sitting in the corner of the kitchen. I didn’t dare try and put it together. But I bought some woodworking glue, Evo-Stik, supposed to be adhesive strong. And the table’s still standing. It was Evo-Stik glue. One night, I just plucked up the courage and thought, ‘Here we go.’ Right at the end, under the table, there was a cross-truss that had to fit in. And I suddenly thought, ‘Oh my God, it doesn’t fit.’ But somehow I wangled it. I turned it upside down and then it fitted. I have an idea of how to do a thing, and then enough passion to follow it through.

CHRIS WELCH: Paul had two great allies when he returned from The Beatles and set off on his new musical career. One, of course, was Linda. And the other was the blank sheet of paper where

he could write down all the ideas for new songs. They were the forces behind Paul then: blank paper and Linda.

PAUL M c CARTNEY: It was weird starting all over again. But it wasn’t the world’s worst thing. It was sobering. It’s good to be knocked off your perch, to get your feet on the ground. There was a lot of that with Wings. Not only was I doing things for myself with the band, I was personally doing a lot of things for myself, living up in Scotland, mowing the field with my tractor. It started to get really nice, and we started to feel very free. I started making music again, because I had my guitar with me and I had a piano. And I built a little studio. I got a guy who’d done a great studio in London, Dick Swettenham, or as I used to call him, ‘Sweaty Dick’. He was fantastic and he set me up a four-track machine, which was how The Beatles had first recorded. So I could just do that on my own and start making little bits and pieces of music.

CHRIS WELCH: It was therapy, really.

PAUL M c CARTNEY: I hung on, wondering if The Beatles would ever come back together again, and hoping that John might come around and say, ‘All right, lads, I’m ready to go back to work.’ In the meantime, I began to look for something to do. Sit me down with a guitar and let me go. That’s my job.

MICHAEL M c CARTNEY: Loving your wife and then having children, there is another form of ‘Beatles’.

CHRIS WELCH: It was Linda who encouraged him to come back, make some music. And later form a band, Wings. He did the best thing possible, which was to write songs about things that appealed to him, whether it was silly love songs or rock and roll. He wanted to experiment and be free to do what took his fancy. Things in everyday life. Cooking. Making breakfast.

PAUL M c CARTNEY: Sometimes you manage just because you’ve got to.

From these modest beginnings, a larger plan began to hatch. After returning to London, Paul began to realise that he was working towards a solo album. To facilitate the work, he borrowed a Studer four-track machine from EMI Recording Studios at Abbey Road and moved it into his nearby home.

The album he was building was a simple, home-cooked affair, not unlike one of Linda’s meals. Paul plugged directly into the back of the Studer and simply estimated the levels. The songs came freely, easily. Now and then, he dropped into a studio – Abbey Road, or Morgan Studios in Willesden – for an enhancement.

The result was a DIY classic, as far from the studio wizardry of Abbey Road as it was possible to be. Paul played every instrument, and sang many of the songs sotto voce, as if speaking intimately to a loved one. Which, in fact, he was, since so many of the songs described the happy domestic life that had helped him through the past year. In every way, this was a family effort, with Linda’s photographs and harmonies adorning the final product.

The artwork included a striking portrait of Paul in Scotland, with his infant daughter, Mary, peeking out of his jacket. Another image, from their holiday in Antigua, revealed a wall covered with cherries. They had been set out to attract birds, an early indication that Wings might be on the horizon.

PAUL M c CARTNEY: I don’t think anyone was sure whether we’d get back together again. So in the meantime, for me it was, ‘Well, I like music. What am I going to do?’ So I got the four-track machine in the house. And just started doing bits and pieces. I would sit around the house with a guitar. From that, I started writing. Just making instrumental pieces. It’s something I still like to do to this day. That was how it started. Just me in the living room at home, with the machine. I wasn’t trying to aim for popular success. I was just doing this because it was fun to sit around the house and make some music. It meant I hadn’t given up. It was some kind of continuum. It was such fun to work that way. No control desk. No millions of wires going everywhere. Just a drum kit, and if I didn’t like the sound, I’d move the mic. Too much cymbal? Put the mic a bit further away, then. It was all lovely and logical and simple and innocent.

MICHAEL M c CARTNEY: He’d go to his house in London, in St John’s Wood, and all these machines would be all over the room, with these tapes going right across the room – these long tapes would go to another machine. He would be experimenting with sound. And he’d be listening to crazy Stockhausen [experimental German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen] and whoever else. Crazy sounds, because of that newfound freedom. You’re not restricted to producing the next number one, so that freedom goes into the mind. I was going to say ‘mindless’. But I mean ‘open’, ‘free’.

PAUL M c CARTNEY: I didn’t really think it was going to be an album. It was just me recording for the sake of it. I’d get up and think about breakfast and then wander into the living room to do a track. The spirit of the times was do it yourself, keep it simple,