The Cultural Tutor

Forty-nine Lessons You Wish You’d

Learned at School

Sheehan Quirke

VIKING

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Viking is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published 2025 001

Copyright © Sheehan Quirke, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception

Set in 12/16.32pt Garamond Premier Pro Typeset by Six Red Marbles UK , Thetford, Norfolk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978–0–241–74285–3

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

For all the people I never met

II.

III. e Language of the World

VI.

Prelude

As I write these words I am looking at a mountain – a hill, really – and it is raining. The time is eleven thirty at night. And I ask myself, ‘What is the right way to start a book?’ You can tell that I’m struggling. Everyone knows the advice: say something to hook your reader. Well, I’m afraid I have no hook. But there are some things I want to tell you, and I think you will find them interesting.

This book is about art, architecture, history, literature, poetry, philosophy, war, technology, and love. That sounds like a lot, but they can all be summed up in a single word: culture. Yes, this book is about culture, the story of what we human beings have done. It started millennia ago and is still being told now, with every passing moment. You are part of this story – and this book is your introduction to it.

Culture is like a language. It can be learned, and anybody can learn it. And, just as learning a language opens up new possibilities, learning about culture changes how you see and interact with the world. There is wonder all around us, endless wonder and fathomless beauty, a hundred million fascinating stories behind every mundane detail of life. With this book I want to help you discover all of that, to help you see the world in a richer and more vivid way.

So this book isn’t just about culture as a thing to be studied. The value of art isn’t ‘knowing about’ art; the value of art is how it reveals to you parts of yourself you did not know were there. Literature will give you solace in your darkest moments; philosophy will help you make better decisions; and history will clarify the problems of the present day. This is the real purpose of education – not knowing for

the sake of knowing but knowing in order to live well and do right, to understand both yourself and the world better. Learning about architecture, for example, has turned every journey I take – be that visiting a new country or going to the dentist’s – into an adventure. Each street – every corbel and cornice – tells myriad tales, and understanding architecture lets you read them. There is more around us, more than we ever quite realise, and culture is what gives us the eyes to see it.

Although these things have always interested me, just a few years ago I knew very little about them. I was curious about the buildings that surrounded me – why did they look like that? I kept hearing about ancient Greece and Rome in books or films but had no idea which came first. Art seemed intriguing, but I thought you needed expert knowledge to ‘get’ it.

Well, three years ago I started exploring culture more deeply and wrote about this journey online. I quit my job and created an X account called ‘The Cultural Tutor’. Soon I had 1 million followers and it became clear that it wasn’t just me who wanted to know more about culture. People really do want to learn about art, history, architecture, and all the rest of it – they just don’t know where to begin. And the internet is, though a potentially fabulous place, too often a tornado of gruelling political arguments, depressing newsflashes, unceasing gibberish, and people trying to sell you stuff. Cultural enrichment is an alternative. It is a place of joy and intrigue, of that ‘something more’ we are always searching out. The popularity of my online writing is testament to the fact that people are, indeed, looking for something – and that in culture we can find it. e Cultural Tutor is the culmination of that work, and of all the things I have learned; it is my attempt to create an introduction to culture, not as a list of factoids or as a product, nor as an academic

treatise or guide to impressing people, but as a way of seeing and understanding the world.

What I have written for you is the book I would like to have read before I began my journey, a book which introduces the different pillars of culture, explaining each in its own way and showing how they are connected. e Cultural Tutor will not tell you everything you need or want to know of course, because the things I’m writing about are illimitable in scope. It is a place of departure, not arrival. And we will travel far together, even through time. Gothic architecture, air conditioning, Lionel Messi, alarm clocks, Socrates, spelling, dying, Kinkaku-ji, and Ragnarök – these, and much else besides, we will glance at. So think of this book, above all, as a cultural primer. It is mainly, though far from exclusively, about what we usually call the West. And so I hope it will serve as a useful primer for anybody interested in Western culture, wherever you are from. But, more importantly than that, its themes and approaches – embracing culture as a way of life – are universal.

It’s hard to know where to begin with subjects like art or philosophy, and even once you do begin there seem to be numberless books to read and multitudinous angles to be studied. This is intimidating and time-consuming. e Cultural Tutor is my attempt to do that work for you, to give you some foundational understanding and provide the knowledge you need to journey further. I have spent my time leafing through battered old books, investigating the shadowy corners of ruined buildings, and staring into the faded pigments of forgotten paintings – now I bring all that to you. Because you can teach yourself about these things, and in the internet age this is more readily possible than ever before. So you don’t need to know anything about the Annals of Tacitus or the differences between Impressionism and Expressionism to read this book; it is your

starting point. Though, even if you do know a thing or two about these subjects, there is plenty in here that will surprise you.

My aim with this book is also to share cultural education more widely. Too often culture is either compressed into thirty-second soundbites, reduced to trivia, or described in a needlessly complicated way. e Cultural Tutor represents a different approach. Because culture is more than trivia and more than a field for experts – it is the water we are all swimming in, and it is something we should all know about. Art, for example, isn’t just for people who have studied art, and it isn’t just for the elite. Art is – always has been and always must be – for everybody. An individual painting or sculpture can seem incomprehensible or ridiculous, but that is usually because it has been presented in the wrong way. The purpose of this book is to sweep away the nonsense that sometimes surrounds culture and give you culture as it really exists, in all its glory and catastrophe, as it relates to you and shapes the world we are living in.

I also wanted to write about things that are not being given the attention they deserve, things that have been sidelined in our age of self- optimisation, be it the origins of how we measure time or the best ways to write love poetry. Because ours is a wide and fantastical world, an awful and miraculous place. More and more I believe a little wonder is what we are missing in our everyday lives. Not mere factoid-wonder but a deep and magical awe. Culture gives us that. And now, more than ever, we need it to remind us that human beings have imaginations and hearts, not just bank accounts and schedules. Remember: culture is the story of everything we have done, and you are part of this story. To help you feel this depth, to live with a sense of perspective, place, and profundity – that is the ambition of e Cultural Tutor.

So here we are. You the reader. Me the writer. Our Earth is turning. Time rushes on. Are you standing in a bookshop? Reading an online preview? Who are you? What did you dream of last night? The only thing I can say for now is that, if you read this wad of paper printed with symbols called letters, glued and bound together, you may find it useful. And we will get to know each other somewhat, even have a laugh along the way!

e Cultural Tutor has been divided into seven pillars. I could have called them sections, I suppose, but that is a brutally boring word. And the metaphor is accurate: each of the pillars that support a building may be beautiful, but they only work through their unity.

The first pillar is about history; the second is about the forces that have shaped that history; the third is about the world we have built, our architecture; the fourth is about those things we inevitably make, our art; the fifth is about thinking, speaking, and writing; the sixth is about ways of living; and the seventh is about our present day.

Each of these pillars has been divided into seven short chapters, making forty-nine in total. You can read them in any order. Some are directly informative and others are more vagrant. There is overlap in places, but it could not be any other way – all these subjects are fundamentally inseparable. To give just one example, you can’t talk about architecture without talking about history, and you can’t understand history without understanding architecture. So certain ideas and themes reoccur, but every time in a different light.

Two more things I should mention.

First: there are lots of quotations in this book. Why? Far more useful to have these voices talking directly to you than me barging in with attempts at summarisation. And, more importantly, I want you to meet first-hand the cast of heroes and villains who have played their part in this great drama called humankind. These quotations also serve as recommendations along the way for further reading.

Second: the world is not limited to the places or people mentioned in these pages. Would I had written of more! But I trust you

to think for yourself. Whatever I have mentioned are examples, not ideals.

All things now said, all preliminary caveating done, any more chance of an introductory thought swift melting away . . . for good or bad, I give you e Cultural Tutor.

The First Pillar of The Cultural Tutor

How Did We Get Here?

Skeuomorphs †

For whatsoever from one place doth fall Is with the tide unto another brought: For there is nothing lost, that may be found if sought.

– Edmund Spenser, e Faerie Queene

In 1889 an archaeologist called Henry Colley March was studying ancient pottery. He came across some clay jars with decorations that looked like twisted ropes. Why did they look that way? People had used woven baskets before pottery. And when they started to make jars with clay, March realised, they imitated the appearance of those baskets. Weaving does make a pretty pattern, but with the baskets it had been necessary. With the clay jars, however, the pattern became purely decorative. March coined a new word to describe this phenomenon: ‘skeuomorph’. Skeuos means ‘tool’ in ancient Greek and morphe means ‘shape’; together they mean ‘in the shape of a tool’. So a skeuomorph is any new invention designed to look like what it replaced, even though it doesn’t need to. But skeuomorphs are not unique to ancient pottery – they are all around us. If you use Microsoft Word I urge you to look in the upper-left corner, at the ‘save’ button. What is it? A floppy disk – even though they became obsolete twenty years ago. Digital phone cameras don’t

have mechanical shutters, but they do make a clicking sound – like physical cameras. Th e Gmail logo imitates an envelope despite neither paper nor postage being involved. I could go on: the desktop recycle bin, the visual paper texture of eBooks, hubcaps that evoke spokes. What is the point of skeuomorphs? There’s no intrinsic need for websites to have a ‘shopping trolley’ represented by a small image of a physical trolley, but when it looks that way we intuitively understand what it is. So skeuomorphs make new technology easier to understand. That being said, sometimes they are purely aesthetic. Cooling vents are only needed for cars with combustion engines, but because a car without a grille looks odd designers have retained them for electric cars.

Eventually we forget where our skeuomorphs came from and they simply become ‘the way things are’. Look at the White House in Washington DC , for example. Look closer, at the columns on its north front. Notice that each of them has decorative swirls. These are called volutes.

Why are they there? Thousands of years ago, Greek temples – which inspired the Neoclassical architecture of the White House – were made with wood, and their columns were timbers. These columns were sometimes decorated with the curved horns of male

sheep. When the Greeks started building with stone they carried across all the original features of the wooden temples – including the spiralling horns, which became volutes in marble. Several thousand years later these petrified horns adorn the house of the President of the United States of America. Curious!

I hope you can see why I have chosen skeuomorphs as our starting point – because they are a supreme reminder of how the past shapes the present, of history. As the poet-historian Thomas Carlyle wrote: ‘The poorest Day that passes over us is the conflux of two Eternities; it is made up of currents that issue from the remotest Past, and flows onwards into the remotest Future.’1

We did not build the world we are living in. Everything we say, think, and do (plus everything we are able or unable to do) has been shaped by people who are no longer alive. Why are there 365 days in a year, 30 (or 31, or 29, or 28) days in a month, 7 days in a week, 24 hours in a day, and 60 seconds in a minute? That’s quite a mess. We can thank Mesopotamians, Egyptians, Julius Caesar, Indian mathematicians, Hebrew scholars, Greek astronomers, and Pope Gregory XIII for it. We are steeped in inherited ideas and systems which we have accepted, unthinkingly, as we found them. Even these words you are reading were created by long- gone generations. And who built the roads you walk along, decided they should be in that particular place, go in that particular direction? More often than not we walk the same roads people walked centuries ago simply because a shepherd decided to build his cottage there or a caravan found it the easiest route to follow on its trade journey. Look at what things are called and you will learn a lot. July, named after Julius Caesar; Wednesday, a corruption of Odin’s Day. The clues to the past are in the present; the past is the present. Maybe you’re sceptical about what I’m saying. ‘The iPhone,’ you

might ask, ‘is that not entirely new?’ But without transistors the iPhone would not work, and the transistor was invented in 1947. And the transistor could not have been invented without silicon, first isolated by Jöns Jacob Berzelius in 1824. Berzelius was only able to do that because of the chemical theories of the Frenchman Antoine Lavoisier, published four decades earlier. Still, Lavoisier would never have formulated them without the pioneering experiments of the Scottish chemist Joseph Black. And Black conducted his experiments with alchemical equipment made of, among other things, glass, invented 4,000 years ago in ancient Mesopotamia, possibly by accident. But glassmaking was made possible only because of the heat produced by metalworking, which was undertaken for the first time by humankind some 10,000 years ago or more. Metalworking itself would have been impossible without fire, mastered long ago in a way that will always remain a mystery. In short: the iPhone in your hand would not exist if our ancestors had not made all these innovations across these many millennia. And that’s not to mention everything else that was needed for these discoveries to occur: law, maths, organised labour, paper, translation, international shipping, and so on. Steve Jobs said as much:

I speak a language I did not invent or refine. I did not discover the mathematics I use . . . I am protected by freedoms and laws I did not conceive of or legislate, and do not enforce or adjudicate . . . I did not invent the transistor, the microprocessor, object-oriented programming, or most of the technology I work with.2

This baggage of history – the things we have inherited, from whole political systems to individual words, which necessarily restrict us – is precisely why some people have tried to start over again. During the French Revolution, for example, the old calendar was replaced

by one with ten-day weeks, plus new names for the months and days. This change didn’t stick – but others, like the introduction of metres and grams, did. Such is the story of civilisation. We can never truly start again, but we can choose how we react to and deal with our past, slowly adding to or removing from what we have inherited. So history matters because we have no choice in the matter; it is with us whether we like it or not. The past seeps interminably into the present. It is not only the story of things that have happened but the story of things that are happening. And so, even if we wish to disregard history, we should at least know what we are disregarding. To quote the Roman statesman Cicero, writing in the first century bce : ‘To be ignorant of what occurred before you were born is to remain always a child.’3

Let us see what history is about, then – let us hang like the Norse god Odin from the Cosmos-tree Yggdrasil, its roots stretching below the earth and its branches into the heavens, to see what we can perceive in the darkness of ages past. The lights go down, the curtains go up, and we begin our journey through time and space . . .

Queries Regarding Postal Permits

Go thou to Rome,—at once the Paradise, The grave, the city, and the wilderness.

–

Percy Shelley, Adonais

We arrive in the fifth century bce . Much is happening. The world is hot-blooded and young. A strange awakening is at work. Siddhartha Gautama is preaching in the hills of northern India; Confucius is teaching in the mountains of Shandong; Hindu poets are composing the Upanishads in the forests of the upper Ganges; Hebrew scribes are giving Genesis its final form; a man called Socrates is wandering Athens. Yes, strange as it sounds, all these things are happening at a similar time – an older age of humankind is drawing to a close, melting like wax before the blaze of something new. Foundations of a different age are being laid, foundations on which our modern world rests.

But where had civilisation come from in the first place? A solemn mystery! Suffice to say it was a long time coming. Homo sapiens had already been walking the Earth for 300,000 years before our ancestors in the Middle East stopped living purely by hunting and gathering and started farming. This was a process that had started, very roughly, in 10,000 bce . But another 6,000 years passed before

full-blown civilisation burst into life. We settled. We built towns. With a town comes a population, law, craft, trade, and politics – civilisation was stirring in the hearts of humankind. Th e flame was first lit during the fourth millennium bce in Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. That was when recorded history started – thanks to the invention of writing. Soon afterwards civilisations arose independently in Egypt, in the valley of the Indus River, in China, on the Gulf of Mexico, and on the coast of Peru.

So, before either Greek or Roman had so much as carved a volute, the Mesopotamians had invented writing and the wheel, the Egyptians had thrown up their Pyramids, and far off flourished the vigorous civilisations of India and China. Why, then, are we always thinking about Greece and Rome? Because history is (usually) written by the victors, and their culture – for good or bad – has been victorious: their ideas, laws, art, literature, and language. ‘Democracy’: the word and concept are Greek; ‘Republic’ is Latin – the language of the Romans – and the names of our planets also. Look any way you will, you cannot but find Greco-Roman fingerprints all over the twenty-first century. And so, perhaps because Greece and Rome permeate our culture – including popular culture: films like Troy or the two Gladiators, plus countless novels, video games, and TV shows – there is an unspoken assumption that everybody knows the basic facts. But I don’t think that’s true. I, for example, once had no idea whether Greeks or Romans came first.

My purpose in this chapter is to give solid form to any vague illusions you may have regarding these two societies which we cannot stop talking about. It will, I hope, help you make sense of various things you perhaps already know or have heard about, and help you put some names to faces and dates to places.

We begin with a word: classical. ‘Classical’, ‘the classics’, or

‘antiquity’ refers to the period from about 500 bce to 500 ce , a thousand-year stretch when Greco-Roman civilisation flourished. First came the Greeks. Their origins lay much further back in time, but by 500 bce they had matured into the society we generally think of today when we talk about ‘ancient Greece’. Crucially, this ‘ancient Greece’ was not a country. It was a collection of independent and oft en- warring cities around the Mediterranean, many along the coast of modern- day Turkey, others in Sicily, France, Egypt, and Lebanon, and around the Black Sea in Ukraine and Bulgaria. These cities were linked by heritage, language, religion, and (perhaps surprisingly) sport. Our modern Olympics were resurrected from the original Greek Olympics, which was the most important of the four Panhellenic Games, to which wrestlers, discus throwers, sprinters, and boxers journeyed from afar to win glory for their city, receive the ribbons of victory, and have their likeness carved in marble or cast in bronze. Greek scholars even dated their history by ‘olympiads’, four- year intervals measured from the first Olympics, instituted by mythical Herakles himself in 776 bce.

The city – the polis – was the basic unit of Greek society. These were distinct cities with their own political systems: some were ruled

by kings, others by aristocracies, and some by assemblies. In 490 bce these cities united against the invading Persian (or Achaemenid) Empire. The Persians had built history’s first true empire, a vast and sophisticated state that stretched from India to the Balkans – but even with all their wealth and power they could not overcome Greece. The Greeks united again in 480 bce to fight off another Persian invasion, and after various legendary battles (including the Battle of Thermopylae, portrayed in the 2006 film 300 ) were victorious. Athens became the most powerful of Greek cities and, with a statesman called Pericles steering its democracy, enjoyed a Golden Age of art, literature, and philosophy. This Athenian zenith is best symbolised by the Parthenon, completed in 432 bce , that temple you have likely seen plastered all over tourist brochures advertising holidays in Greece.

But the Athenian Golden Age did not last. The intra- Greek Peloponnesian War concluded with Athenian democracy toppled and Sparta – Athens’ great rival, a city with a famously militaristic culture – triumphant. Then another city, Thebes, rose to crush Sparta; Thebes crumbled in turn. The polis, even if fertile ground for science and philosophy, was incompatible with political unity.

Somebody else would have to do the unifying for them . . . and did: King Philip of Macedon, whose kingdom lay just to the north. By 337 bce he had made himself ruler of Greece. But Philip was assassinated by a fame- seeking bodyguard, and so it was his son, Alexander (later the Great), who set out to realise both his father’s ultimate dream and the dream of all Greeks. Within a decade he had smashed the Persian Empire and led his armies to the Hindu Kush. But in 323 bce , after a hard night’s boozing, Alexander the Great died. His empire then splintered into kingdoms ruled by his generals.

These conquests ushered in the ‘Hellenistic Age’* – a period when Greek culture was dominant from Egypt to Afghanistan.

What about Rome? Legend says it was founded in 753 bce by wolf-suckled Romulus, a descendant of Aeneas, the prince who fled Troy when it was besieged by the Greeks with their wooden horse.† Well, be that myth or truth, Rome’s early days are explained succinctly enough by Tacitus, a Roman historian who lived in the first century ce . This is the first line of his Annals: Rome at the beginning was ruled by kings.4

Yes, there were seven kings of Rome! But in 509 bce a man called Brutus led a revolt and established the Roman Republic. During the great Greco-Persian Wars it would have been laughable to suggest that this piddling Italian city would eclipse them both . . . but that is what happened. Rome conquered the Italian Peninsula and then went to war with the Carthaginians, an ancient kingdom centred on what is now Tunisia. It was in the second of these wars that Hannibal of Carthage travelled with his elephants through Spain, along the French coast, over the Alps, and into Italy, where he terrorised for a decade. In the end these invaders were pushed back to Carthage and defeated. That was in 202 bce . Sixty years later the Romans had also conquered Greece and Macedonia. In short: this republic was no longer just a city.

So, perhaps inevitably, by the first century bce Rome had grown too large for its republican constitution. Ceaseless strife ensued. Julius Caesar conquered Gaul, modern- day France, and a rival

* So called because the Greeks referred to their broader nation as ‘Hellas’ and to themselves as ‘Hellenes’.

† This quasi-mythical Trojan War is purported to have taken place in about 1200 bce , long before the rise of classical culture.

general called Pompey extended Roman territory into the Middle East. These men could not share the republic and so they fought for it. Caesar won and became ‘dictator for life’. In 44 bce the last dregs of republican spirit were channelled in a man called Brutus, descended from that very Brutus who first established the republic. He joined a group conspiring against the dictator – and Caesar was assassinated. Arise Octavian, Caesar’s heir, who won his own civil wars and rebuilt the republic around himself. There was no king in the Roman constitution, but Octavian, in 27 bce proclaimed Augustus by the Senate, had effectively become an emperor.

Then followed the Pax Romana, or ‘Roman peace’, when Rome was a single state stretching from Spain to Saudi Arabia, with its famous legions along the borders. Every province was connected by extensive and well-maintained roads. Bridges spanned onceimpassable chasms, aqueducts brought fresh water into cities, and villas had underfloor heating. There were public baths, theatres, and stadiums in every town. New hairstyles became fashionable and bookshops were stocked with the latest poetry. There were fire brigades, a postal service, traffic regulations, building codes, annual budgets, tax incentives, and citizenship rights. Laws were consistent across thousands of miles and architecture was the same on three continents. There was even a welfare state, with thousands of citizens living on the ‘grain dole’. That little city had come a long way.

But, if Rome ended up politically dominant, why do we say ‘Greco-Roman’? Because the Greeks conquered their conquerors with culture. Every educated Roman spoke Greek and admired Hellenic art and literature. Just two examples of how extensively ‘Greekness’ permeated Rome are that the emperor Marcus Aurelius wrote his famous Meditations in Greek, not Latin, and that its very philosophy of Stoicism also originated in Greece. So the rustic

France Syria Jordan

Tunisia

Lebanon

Turkey Portugal

Italy Spain

e same Roman architecture on three continents.

Romans had been Hellenised. And in the end they were Christianised too. Although the followers of a certain Galilean upstart called Jesus were at first persecuted by the Roman regime, the Christian faith eventually won the war of ideas. In 380 ce Christianity became the state religion of the empire and the temples of the pagan gods were closed down.

Enough! That was a lot of information – dates, names, and places – in quick succession. I have given you facts, but what of feelings ? I think we should look at the story of a man born near Lake Como in 61 ce , raised by his mother and educated by his uncle. His

name was Pliny the Younger. In Rome he studied under the great rhetorician Quintilian and (after witnessing the eruption of Mount Vesuvius) embarked on a career in inheritance law, though he also prosecuted corrupt officials before the Roman courts. He also helped out at the treasury and even ended up as governor of a province called Bithynia, in the north of modern Turkey. But Pliny is not remarkable for his career. It is through his letters (published in his lifetime) that we remember him. Epic poetry, great deeds, and sombre statues can make the classics seem distant. But Rome comes to life with Pliny – because we see it through the eyes of somebody simply living there.5

Chiding a friend, Fabius Justus, for ghosting him:

I have not heard from you for a long time, and you can’t say you have nothing to write about because you can at least write that.

Complaining about sports fans to Calvisius Rufus:

The Races were on, a type of spectacle which has never had the slightest attraction for me. I can find nothing new or different in them: once seen is enough, so it surprises me all the more that so many thousands of adult men should have such a childish passion for it.

Telling his wife, Calpurnia, he misses her:

I, too, am always reading your letters, and returning to them again and again as if they were new to me – but this only fans the fire of my longing for you.

Or, to the emperor Trajan, trying to figure out the postal service:

Are permits to use the Imperial Post valid after their date has expired, and, if so, for how long?

He was not one of the poets, philosophers, or warriors who dominate talk of Greece and Rome. Pliny was just a man – pragmatic, tender, and hopeful. As he wrote to Valerius Paulinus:

So we must work at our profession and not make anyone else’s idleness an excuse for our own. There is no lack of readers and listeners; it is for us to produce something worth being written and heard.

In some ways, then, cosmopolitan Rome is startlingly familiar to us. Another example is sport. Not long ago the French footballer Kylian Mbappé turned down a potential $1 billion deal that would have seen him play for the Saudi Arabian football team Al-Hilal – but this would not have made him the highest-paid athlete in history. That was Gaius Appuleius Diocles, a charioteer from the province of Lusitania, modern-day Portugal. There were four factiones, or teams, in Roman chariot-racing: Green, Red, White, and Blue. These were professional organisations with their own stables, managers, breeders, racers, and raucous fans. At the age of eighteen Gaius debuted with the Whites. Seven years and a pitiful spell with the Greens later, he joined the Reds. There he remained for fifteen years, winning over a thousand races and retiring at the age of forty-two. Where did Gaius race? At the Circus Maximus in Rome, now a ruin but once a stadium that held at least 150,000 spectators. Two monuments erected in his honour record the statistics of his career – 4,257 starts and 1,463 victories – and his total prize money: 35,863,120 sesterces (which one estimate puts at the equivalent of about $15 billion today). What does it say about Roman society that regular people had enough time, and that there was enough money in the system, to support such a huge sporting scene? The Colosseum held 80,000 spectators, which even by today’s standards makes it a major venue, and it was just one of several

hundred Roman arenas all around Europe. This culture of mass entertainment is not so dissimilar from our own.

As for what they watched in these arenas . . . therein lies some diff erence: men and beasts fi ghting to the death. Th e Romans’ fascination with oracles and augurs is also strange to us – priests studying the skies for instructions and examining sheep guts to make military decisions. And we cannot forget that slavery was ubiquitous in the Greco-Roman world,* along with legally permitted brutalities of the sort we would rather not imagine. Just take this little piece of Roman legislation, enshrined in the Laws of the Twelve Tables of 449 bce : ‘A notably deformed child shall be killed immediately.’6

What happened to the Roman Empire in the end? A Roman citizen in the time of Pax Romana would surely have presumed (as many of us tend to think about our own today) that their civilisation would last forever. But, through a mixture of decadence, political atrophy, mass migration, war, economic downturn, and the death throes of civil war, it started to go wrong. The civilisation of Rome did not ‘fall’ overnight – it bled to death as books ceased to be written, the Senate stopped meeting, chisels fell quiet, and outposts fell, all until the final Western Roman emperor, by fate-twist called Romulus, was deposed in 476 ce .† A thousand years of Greece and Rome had breathed their last . . . for a while.

Because nobody forgot Rome. After all, even today there is not

* Though, that being said, a Roman slave could change their legal status. Pallas, a ‘freedman’ (as former slaves were called), became one of the richest men in Rome under Emperor Claudius. Yes, there was even social mobility – several emperors were the sons of peasants! † The empire had been split in two and its eastern half survived for another thousand years as the ‘Byzantine Empire’. They did not call themselves the Byzantines, however. That name is an invention by later scholars. It came from the old name of their capital city, Constantinople, which had once been called Byzantium – and which now goes by a third name: Istanbul. The Byzantines, meanwhile, called themselves Romans.

a twenty-mile stretch in Europe without some Roman road, bridge, viaduct, sewer, or temple, and beneath the barley a broken marble torso, in the seaweed a fist of bronze. Rome lingered as a backdrop to the Middle Ages: its systems morphed into the Catholic Church, the Dark Age king Charlemagne declared himself ‘Holy Roman Emperor’, and ancient philosophy underpinned medieval scholarship. Eventually ‘pure’ Greco-Roman culture was consciously resurrected during the Renaissance, beginning in the fifteenth century. Then, in the centuries following, the foundations of our modern world – among them the Scientific Revolution, the Enlightenment, and the Industrial Revolution – were laid.

But who am I to talk? The garrulous Greeks and gossipy Romans will tell you about themselves: fragments of Sappho, odes of Pindar, epics of Homer and Virgil, mythologies of Ovid, letters of Seneca, geographies of Strabo, travelogues of Pausanias, philosophy-poetry of Lucretius, love-poetry of Catullus, speeches of Cicero, dialogues of Plato, histories of Herodotus and Thucydides, of Polybius and Livy, biographies of Plutarch and Suetonius, diaries of Caesar . . . it’s all there, some glorious, some tedious, some too filthy to reprint. Want to know about the Greeks and Romans? Ask – and they will answer.

e Sixth Age

Although we read that wine is never for monks, in our times it is impossible to persuade monks of this.

– from the letters of Saint Benedict

Antiquity melts and another thousand-year epoch arises, vast in scope and half inscrutable: the Middle Ages. We still cannot make up our minds about them. Were they a grim and plague-ridden whirlpool of illiterate tyranny? Or were they a glittering age of knights, chivalry, and Robin Hoods? There was something of both in those long centuries. But understanding the Middle Ages – even surrounded as we are by their remnants, the cathedrals and castles and abbeys looming up from what seems like a lost civilisation – can be strange and difficult work. First of all, I think there are some common myths about the Middle Ages that should be dispelled. Four, in particular. First: medievals did not think the world was flat. That is nineteenthcentury American propaganda. Second: they were not the drab people depicted in films or on television. The Middle Ages were, as surviving clothes and art attest, a time perhaps more colourful than our own. Third: the frequent and crude definition of the Renaissance as a ‘rediscovery’ of classical civilisation is inaccurate. Medieval writers knew all about the classics; they just thought of

them differently. Fourth: although many a peasant never strayed beyond their parish borders, many a monk, mason, composer, and soldier did . One letter written by Abbot Cuthbert in northern England to the Archbishop of Mainz in Germany in 758 ce , in the darkest of those so-called ‘Dark Ages’, illustrates this: If there is any man in your diocese who knows how to make glass vessels well, when a suitable occasion presents itself, kindly send him to me . . . It would please me also to have a zither-player . . . for I have a zither and do not know how to play it.*7

Enough myth-busting. If we are to make up our minds about the Middle Ages we must figure out what they were. And the best way to do this is by trying to discern the medieval worldview. So here is our point of departure: a little gargoyle carved upon the walls of a church, a bawdy ‘work of art’ in a sacred place. It is confusing to us now that ribaldry and sanctity went so readily hand in hand. But by looking at this strange object we grasp just how much our ways of thinking have changed. Time to investigate.

We in the twenty-first century consider other people our equals, differentiated from us only by changeable things like the job they happen to do. There is nothing (according to the prevailing philosophy

* A diocese is the area over which a bishop has authority and a zither is a type of stringed instrument.

of our democratic-consumerist-capitalist system, at least) that you or I would be able to do that anybody else could not also do. We choose who rules us – we can even enter politics and be elected ourselves. To understand the Middle Ages you must forget all of this. In those days people were mostly part of a fixed, hierarchical order. A lord was your lord and that was that; no such thing as a vote. With some exceptions (and admittedly more than we might suspect) you were allotted your position in life at birth and got on with your designated duties. So, where we are bound to other people by general laws and by whatever contracts we have chosen to enter, the medievals were bound to other people by the mutual responsibilities and obligations of their status.

That may sound like tyranny or chaos to us, but a thirteenthcentury encyclopaedia compiled by Bartholomew Anglicus, e Properties of ings, tells us how and why this system worked:

A rightful lord, by way of rightful law, heareth and determineth causes, pleas, and strifes, that be between his subjects . . . putteth forth his shield of righteousness, to defend innocents against evil doers, and delivereth small children and such as be fatherless, and motherless, and widows, of them that overset them. And he pursueth robbers and rievers, thieves, and other evil doers.8

Medieval aristocracy was not like aristocracy as it still exists in parts of the world today, largely as a historical relic; Medieval lords were governors, soldiers, and judges on whom thousands relied for peace and their livelihood.

Intermingled with all this was the Church, headquartered in Rome. One way to think of it – and it’s not wholly wrong – is like the European Union: a colossal organisation with officials and establishments in every corner of the continent, creating multinational regulations and constantly in tension with local governments. That

being said, we risk garbling the past by seeing it through the lens of the present. In our secular and rationalistic world, the Church – and all medieval religion – makes no sense. Just as you would not ask somebody, ‘Do you breathe oxygen?’, a person in the twelfth century would not have asked, ‘Are you religious?’ Christianity permeated everything. It was not part of culture; it was culture. And people took their religion very seriously. Consider what a knight called Sir Jean de Joinville wrote about the Fourth Crusade, which began in 1202:

A little later the Pope sent one of his cardinals, Monsignore Pietro de Capua . . . to proclaim on his Holiness’ behalf: All those who take the Cross and remain for one year in the service of God in the army shall obtain remission of any sins they have committed, provided they have confessed them. The hearts of the people were greatly moved by the generous terms of this indulgence, and many, on that account, were moved to take the cross.9

Would you crusade for the promise of the remission of your sins? No. But you might for money. What to us is financial gain was in medieval times salvation, and this is something we struggle to grasp. People were also motivated by money or power in those days, of course, and in their own writings they make it very clear how frequently. But trying to understand the workings of the Middle Ages through money or politics alone will leave us forever scratching our heads. Then again, we will never grasp anything about the Middle Ages unless we first remember that medieval people did not think of themselves as living in the ‘Middle Ages’. Those words were invented by Renaissance scholars who sought to bring back the culture of Greece and Rome. What to call those ten dingy centuries of ignorance between the creation and the revival of classical culture? The ‘middle’ ages, of course. Medieval people, meanwhile, thought they

were living in the Sixth and Final Age, one that had dawned with Christ and would conclude with Judgement Day.

Nor did they have any concept of ‘progress’ as we understand it; they did not share our general view of the human story as a steady and certain process of improvement. They did not worship humankind as we do now, as Greeks and Romans did. They were eagerly awaiting Doomsday, the end of the world. Material progress makes no sense when it is spiritual preparation for the Final Judgement that matters most. As Thomas à Kempis, a fifteenth-century priest, wrote in a wildly popular book called e Imitation of Christ :

Keep thyself as a stranger and a pilgrim upon the earth, to whom the things of the world appertain not. Keep thine heart free, and lifted up towards God, for here have we no continuing city . . . If it is a fearful thing to die, it may be perchance a yet more fearful thing to live long.10

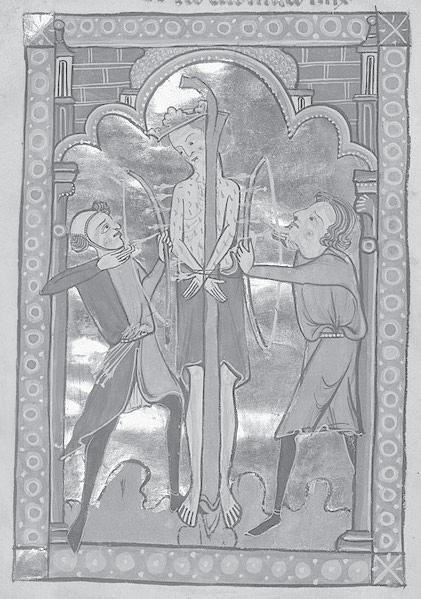

Classical statues of athletes tell us how highly the Greeks and Romans thought of humankind, how they revered our might and beauty; medieval art gives a somewhat different impression.

Medieval people did not think of the universe in the way we do: scientifically. A bird was not an evolved biological machine of respiratory and digestive systems – it was the freedom to which a human soul might aspire. When you see a flower, what do you see ? Something to be purchased? A type of plant? Something pretty? This is what Beatrice saw in Dante’s Divine Comedy, an epic fourteenth- century poem charting one man’s journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven:

. . . here is the rose,

Wherein the word divine was made incarnate; And here the lilies, by whose odour known The way of life was follow’d. 11

Medieval people had a much more symbolical worldview than we do, and so they loved allegory – stories where every ‘thing’ was a symbol for some vice or virtue. Their stories often took place in dreams, as in the fourteenth-century poem Piers Plowman, whose protagonist repeatedly falls asleep and has visions of the end of the world. What is real and what is a symbol? All was intertwined. Consider this fifteenth-century Flemish tapestry: a fair lady between a unicorn and

a lion, surrounded by fruits, flowers, trees, birds, goats, and rabbits. Is it supposed to be a real garden? I suspect we are already losing when we ask that question.

The people of the Middle Ages also had a peculiar sense of humour and readily mixed sacred with obscene, deathly with satirical, beauty with ugliness. We see this humour in the marginalia of manuscripts, created by monks, which so often featured strange drawings of (for example) horse-riding rabbits in armour shoving lances up priestly buttocks. Hard to say what was going on. But the key to the medieval worldview lies in their art, as does the worldview of any age. Look at the gargoyles on church towers, or the misericords (carved seats in choir-stalls), where we find angels and drunkards, prophets and monsters, crowded together. Here medieval aesthetics – whereby the scatological, fanciful, affectionate, and nightmarish were equally welcomed into sacred spaces – is revealed most clearly.

Th is explains why the medieval imagination feels fundamentally diff erent to ours. Because, although they could be darkly

comic and hair-raisingly ribald, in their stained- glass windows we also fi nd an astonishing purity of spirit and depth of devotion. Th ese windows were expensive, and workers’ guilds would club together to pay for them. Would we club together to pay for such things? It seems the medievals neither took themselves too seriously nor looked on humankind with malice. Th ey walked a ‘via media’, a middle way, encompassing all, at once pious and profane, ever revolving around the fulcrum of religion.

And yet, however hard we must work to recognise that the Middle Ages were incredibly different, we would be wrong to think its people were entirely unlike us. There are many voices I could call on, but nobody speaks to us with such timeless clarity as Héloïse d’Argenteuil. She was a brilliant woman, erudite and tender, involved in a love story for the ages, more bittersweet by far than any Romeo and Juliet. I cannot recount in full the tale of her tragic affair with Peter Abelard, the radical celebrity-philosopher of twelfth-century France. All I can do is implore you to read their letters and discover it yourself.

The pleasures of lovers which we shared have been too sweet – they can never displease me, and can scarcely be banished from my thoughts . . . Even during the celebration of the Mass, when our prayers should be purer, lewd visions of those pleasures take such a hold upon my unhappy soul . . . Men call me chaste; they do not know the hypocrite I am.12

You see, then, that their times were different, but they were not. Is there anything incomprehensible in what Héloïse said? Let us not be afraid to look these medieval people in the eyes and ask, ‘Who are you?’ There is no shortage of chroniclers, bards, poets, scribblers,

painters, and historians who can speak to us directly, even in our digital age.*

Why did the Middle Ages end? The Renaissance. An intellectual fire was lit in the fifteenth century that burned up the medieval world, and within a century or two it was turned to ash: status, fealty, freemen, wandering masons, travelling troubadours, dreamallegories, gargoyles . . . their time in our world was done.

Th is chapter has painted a somewhat rosy picture. There was a lot of trouble, a lot of awfulness, in those times. Even medieval chroniclers themselves do not hesitate to describe the brutalities and darknesses they witnessed; the Fourth Crusade in which Sir Jean de Joinville took part, for example, culminated in a carnival of violence and desecration. I will say more about these miseries and hypocrisies later in this book. For now, at least, only remember that those thousands who were burned at the stake or slaughtered in sieges, that uncountable mass of forgotten and ordinary folk who were exploited and ground into dust, these and thousands more must stand between us and any medieval romanticising. My hope has simply been to shed a little light on the Middle Ages, to redeem from the total condemnation of barbarism an age that also had in it beauty, love, and joy.

And before we leave them another caveat should be addressed: referring to the ‘Middle Ages’ is a European way of organising history, and so it is ill-suited to classifying the past of other places.

* Some were garrulous and others were thriftier of word. In the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, steadily maintained for six centuries, we find that all somebody thought worth mentioning of the entire year of 773 ce was this! ‘In this year a red cross appeared in the sky after sunset. This same year the Mercians and the Kentishmen fought at Oxford, and strange adders were seen in Sussex.’

While things were going on in Europe – which has been the broad focus of this chapter – a lot was going on elsewhere. Tsar Simeon raised up the First Bulgarian Empire and nearby the Byzantines reigned in Constantinople. Far away, though linked by trade, Mansa Musa reigned in Mali; meanwhile, in Ethiopia, a king called Gebre Meskel was busy creating his own version of Jerusalem. For a time the Mongols ruled half the world, though they eventually splintered into dynasties like the Ilkhanates and Timurids in Central Asia, and the Yuan in China. Between all lay India, the eighth continent. From Arabia rose the Rashidun caliphate, followed by Umayyad, Abbasid, Mamluk, and a dozen more great Islamic societies stretching from Córdoba to Cairo. We could go on. My point is that there were also Ottomans, Georgians, Khmers, Kievan Rus’, Maya, and a hundred more civilisations that thrived during what Western Europeans have called the Middle Ages.

Dreaming when Dawn’s Left Hand was in the Sky I heard a Voice within the Tavern cry, ‘Awake, my Little ones, and fill the Cup Before Life’s Liquor in its Cup be dry.’

– Omar Khayyam, e Rubaiyat

How did people wake up before alarm clocks? How would you wake up tomorrow if you couldn’t set an alarm on your phone? Solutions in the past weren’t always elegant – in the nineteenth century there were ‘knocker-uppers’ paid to hit your window with a stick.

But the first question, of course, is how people kept track of time at all. For millennia it was through observation: the movement of the Sun by day and the Moon and stars by night. So it makes sense that the first devices for measuring time were sundials. After sundials came more complex inventions. In both Greece and China water clocks were used, which relied on the carefully calibrated flow of water from one vessel into another. Plato is said to have combined one with a water organ and created a rudimentary alarm clock. Later, in the Middle Ages, came church bells and the adhan, the Islamic call to prayer. Both sounded at regular times throughout the day to mark hours of worship and gathering. So bells and muezzins