British voyages that changed the world forever – and the rebels who resisted

Illustrated by Jen Khatun

Also by Sathnam Sanghera

Stolen History

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Puffin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

www.penguin.co.uk www.puffin.co.uk www.ladybird.co.uk

First published 2025 001

Text copyright © Sathnam Sanghera, 2025 Illustrations copyright © Jen Khatun, 2025

The moral right of the author and illustrator has been asserted

The brands mentioned in this book are trademarks belonging to third parties

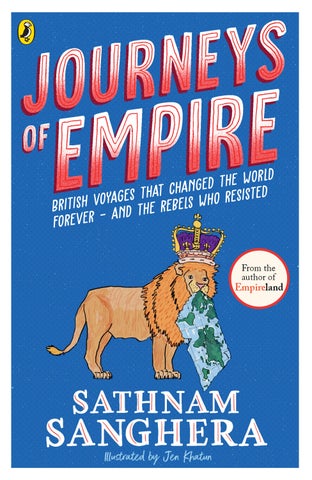

The map on pages vi–vii includes data from Dimitrios licensed from AdobeStock (under licence number 565858264).

The diagram on page 48 includes data from Archivist licensed from AdobeStock (under licence number 162386071).

The illustration on page 158 includes material from Archivist licensed from AdobeStock (under licence number 247743419).

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Set in 10.5/17pt Sabon LT Std Typeset by Six Red Marbles UK, Thetford, Norfolk Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978– 0– 241– 74141– 2

All correspondence to:

Puffin Books, Penguin Random House Children’s One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW

Penguin Random Hous e is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. is book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

My thanks to Jessica Bullock, Sarah Chalfant, Phoebe Jascourt, Alan Lester, Lottie Moggach, Catherine Phipps, Michael Taylor and Kate Teltscher.

INTRODUCTION

Think of something really, really big, and I bet that the British Empire was bigger. Russia? Not a bad place to start: it’s the largest country in the modern world. It covers a staggering 6.3 million square miles and about eleven per cent of the world’s land surface. But no, it isn’t bigger than the British Empire was. The British Empire covered nearly 14 million square miles, or a quarter of the planet’s land surface, at its height in 1923 – this is more than twice the area that Russia covers today.

What about Pluto? I assume you mean the dwarf planet rather than the cartoon dog? Funny you should suggest it, because Pluto’s surface area is roughly the same size as Russia. So again, the British Empire, when it reached its height, on Saturday 29 September 1923, was more than twice as big as this entire dwarf planet.

The moon? OK , you might have got me there. But only just. The surface area of the moon is about 14.6 million square miles, which is slightly bigger than the British Empire at its height. BUT only just. AND if you counted all the countries that had ever been part of the British Empire, it would cover a larger area than the surface of the moon.

In fact, the British Empire was involved with countries beginning with nearly every letter of the alphabet! The British Empire was massive! Bigger than

a Big Mac. Bigger than Big Ben and Bigfoot. Bigger than the Notorious B.I.G. By 1923, 460 million people were living in the British Empire, or one fifth of the world’s population at the time, and, covering some 14 million square miles, it was 150 times the size of Great Britain!

Let’s face it, the British Empire is the biggest thing we ever did as a country. Bigger than winning both world wars, bigger than winning any number of World Cups in any number of sports, bigger than inventing James Bond, Harry Potter, Paddington Bear, Peppa Pig and The Lord of the Rings combined. Yet we don’t talk about it much. It only gets a small mention on the national curriculum, which guides schools on what to teach. And there aren’t many films and novels that tell us the story of the British Empire, compared to all the films that have been made about the First and Second World War (and approximately twenty-seven James Bond films, eleven Harry Potter films, six Lord of the Rings films, four Peppa Pig films and three Paddington Bear films).

You might be thinking, I get it. The empire was big and sounds pretty impressive. But what was it exactly?! And why should we be talking about it? Well, an empire is a collection of nations under the control of another nation or government. Usually the more nations you invade and conquer and ‘colonize’ (meaning taking over

a place to control it), the more powerful you become. Many leaders throughout history have wanted to create an empire. The Roman Empire, which started in 27 bc and lasted for approximately 500 years, was one of the best known. During this time, the Romans conquered Britain and many other regions in Europe and beyond.

Most people agree that Britain’s empire started in about 1600 when Elizabeth I ruled. At the time, Britain ruled over a large portion of Ireland, and lots of seafaring explorers became interested in visiting other countries in search of valuable goods and materials. Britain’s empire lasted for some 400 years, and other European nations, including France, Portugal, Spain and the Netherlands (also known as Holland), too had empires around the same time. However, Britain’s empire was the largest in history. It was seven times larger than the powerful Roman Empire.

The British ended up colonizing lots of different countries, for lots of different reasons. Sometimes it was to trade in food, spices, cloth and other goods; at other times it was to take British prisoners abroad and leave them in another country. The British also gained control of these nations in lots of different ways. There were times they got control through trade and business, but there were also times they did this

through violence. Sometimes they used both methods at the same time.

The British Empire also benefited from the evils of the transatlantic slave trade for a very long time (which I discuss in Chapter 3). If you want to know more about how this all happened, there is further information in my first book on empire for children, Stolen History.

So why don’t we talk about it very much? Well, I’ve thought about it a lot, and I think one reason is because the British Empire is now largely gone. Apart from fourteen small British-run areas, including Gibraltar in the Mediterranean, the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic Ocean, and Bermuda in the North Atlantic Ocean, it doesn’t really exist. And it’s very easy to forget about something that you can no longer see. Like the socks I dropped behind my bed the other day. Or my old collection of Paddington Bear toys.

It might also be because people who are teachers now weren’t taught about the British Empire when they were at school, so they don’t know how to teach it to children today. I mean, you’d struggle to tell people about how algebra and contour lines worked if you’d not studied them in maths and geography, right?

But I think the main reason we don’t talk about the British Empire enough is because it was so complicated.

INTRODUCTION

And as you’ll know from facing any difficult work at school, the easiest thing to do in the face of complicated things is to talk about something else instead. Believe me, I’ve been tempted. I have written several books about the British Empire and sometimes I wish I had chosen to write about Peppa Pig instead.

But we need to understand it and talk about it. Because the British Empire explains a lot of things about the world and Britain. It explains how entire countries like Nigeria and Pakistan came into existence. It explains why many British charities do so much work abroad. It explains some of the racism we see around the world. It explains why Jamaicans eat breadfruit and why Indians drink so much tea. And it partly explains why so many people speak English across the planet.

But how do we even begin to tell this massive story? Almost all the adult books on the topic are incredibly long. Jan Morris, a Welsh historian and author, wrote three books on this subject called Pax Britannica, and they come to well over 1,500 pages in total. My two adult books, Empireland and Empireworld, run for nearly 800 pages combined.

Luckily for you, this one won’t be quite as long. In this book I want to tell you all about what happened through the stories of people travelling through the British

Empire at different times. The journeys I’ll talk about are all very different. Sometimes they involved sailing for hundreds or thousands of miles; sometimes they involved walking for hundreds or thousands of miles. Sometimes the people chose to go on their adventures; at others they were forced or tricked into doing so. Sometimes the journeys were taken by people trying to expand the British Empire; sometimes they were trying to stop it in its tracks. Sometimes I’ll be describing just one imporant journey that a certain person went on; at other times I’ll be describing the many journeys that a particular person went on during their lifetime.

As we go along, I’ll also give you examples of things in our modern world that have their roots in the British Empire – foods, places, countries that wouldn’t exist at all, or would exist in a different form, if the largest empire in history hadn’t happened.

Are you ready to take a trip through the monumental journeys of the British Empire? We’ll be travelling both with a king and queen in luxury to India, and a young enslaved man on one of the most brutal journeys in history, on a boat across the Atlantic Ocean. We’ll be climbing mountains that had not been climbed before, and visiting lands that people in the West didn’t realize even existed. We’ll be seeing London through the eyes of an Indigenous

American whose people knew very little about England, and experiencing Tibet through the hostile eyes of some of its first-ever foreign visitors. The one thing all the journeys have in common, though, is that they shaped the British Empire and the future of the world.

CHAPTER 1

In the twenty-first century it doesn’t take long to get from London to Dublin in Ireland: by plane it’s a journey of just one hour and twenty minutes. Before the invention of air travel, however, it would take quite a lot longer; a steamship and train in the 1900s would make the journey ten to twelve hours long. Before this, in the 1600s, when people had to travel by sailing ships, and when Ireland was the site of England’s first ‘colony’, it could take an enormous amount of time, between five and fourteen days. And you’d have a lot more to worry about than simply losing your passport, or not being able to recharge your iPad or running out of M&Ms on the plane.

The Irish Sea had a reputation for storms and rough waters. ‘As unquiet as the Irish sea’ was a common English saying. This was more serious than a touch of seasickness. Ships could get caught in storms; in 1606

Sir Thomas Ridgeway spent two days stranded at sea, as his ship was tossed around by the waves during a perilous storm. Or crew and passengers could even be shipwrecked, with their boat shattering to pieces against rocks, and the people falling overboard.

And then there was the risk of pirates storming the ship, robbing it and perhaps leaving their victims for dead. English, Welsh, Scottish and Irish pirates operated

in the Irish Sea, using boats called galleys, which descended from Viking longboats. These boats had both a sail and oars, with two or three men on each oar. Sometimes they captured fishermen and forced them to become pirates themselves.

Now, when I mention pirates, you probably have an image in your mind. After all, they’re everywhere, in films like Pirates of the Caribbean , in books like Treasure Island , in video games like Assassin’s Creed IV . There’s Captain Jack Sparrow. Captain Hook. Long John Silver. Blackbeard. And then there’s the infamous pirate who reportedly buried a lot of fabulous treasure that has never been found, and who was hanged and his body left rotting over the River Thames as a warning to others not to follow his path. His name was Captain Kidd.

What these pirates have in common – whether they are real or from books and films – is that they are typically seen as rebels and crooks. And, of course, they are all men. The fact is, though, that not all pirates who attacked and robbed ships at sea were rebels. So-called ‘privateers’ did the same kind of thieving but with the permission of the authorities. Often the only difference between a privateer and a pirate was a piece of paper, a letter from a king, for example, giving them permission