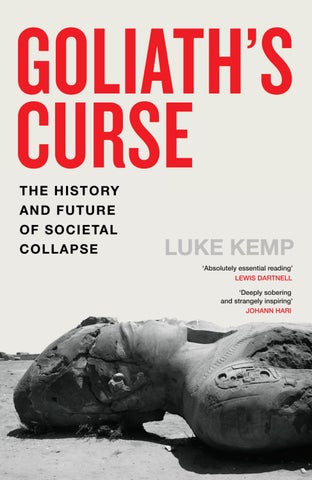

‘Absolutely essential reading’ LEWIS DARTNELL

‘Deeply sobering and strangely inspiring’ JOHANN HARI

‘Absolutely essential reading’ LEWIS DARTNELL

‘Deeply sobering and strangely inspiring’ JOHANN HARI

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Viking is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published 2025 001

Copyright © Luke Kemp, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception

Set in 10.5/14pt Sabon LT Std Typeset by Jouve (UK ), Milton Keynes Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

HARDBACK ISBN : 978–0–241–74123–8

TRADE PAPERBACK ISBN : 978–0–241–74124–5

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

For my brother David

Unravelling History Through Collapse – Goliath’s Curse – Our Fragile Future – A Blessing in Disguise – A 1 per cent View of History – Is History Relevant for the Future? – A Historical Autopsy

Unravelling History Through Collapse

Human history is the story of a power struggle. Power comes in four different forms: control of decision-making, including by setting up a centralized government; control of the resources that others depend on, such as the wheat and rice that most people eat every day; control through threats and violence; and control of information to understand and manipulate others, whether by a bureaucracy, a priesthood, or a big tech company. Then there is the great amplifier: power depends on who you are controlling – the size, skills, and health of the population.1

Each of these power structures can fall apart. When a government – whether in ancient Rome or modern-day Somalia – falls apart, we call it a state collapse or ‘state failure’. When the economy breaks down, as with the Great Depression in the 1930s, we call it an economic collapse. When a large number of people die, we call it a ‘bust’ or population collapse. When all these power systems crumble together in a relatively rapid and enduring manner we call it a societal collapse.2 Societal collapse has shaped our history and will determine our future.

Around 500 kilometres south-west of modern-day Chicago, a city of flat-topped earthen pyramids rises above the Mississippi River. At one stage there were almost 200 of these mounds covering around thirteen square kilometres. The largest pyramid – Monk’s Mound – stands at almost thirty metres, making it taller than the White House. These flat-topped pyramids were made by hand. Villagers would dig up the rich soil, transport it with baskets, and layer it carefully to form miniature mountains. They surrounded a grand plaza 490 metres long and 265 metres wide. The layout was eerily similar to those found over 2,000 kilometres south-west, in the pyramid cities of Mesoamerica.3

This is Cahokia, the first true city of the US (Figure 1).4 Around 1,000 years ago (1050–1100 ce ), the settlement grew into a city of 10,000–15,000 people.5 Just a century or so earlier in 900 ce corn had been introduced to the area. The boom in agriculture, construction, and population was accompanied by more disturbing practices. Within the abandoned pyramids lie the remains of hundreds of men and women. One of the mounds (Mound 72) contains 272 burials, many of which were ritual sacrifices. They were killed and then tossed into graves as part of an elite funeral.

One burial site alone has the skeletons of fifty-three women, all of which are of reproducing age: fifty-two are fifteen to twenty-five years old and one was around thirty-five. The women may have been virgins, or a harem of slaves. Another pit contains four men with their heads and hands cut off. Other victims kept their hands but suffered slower deaths, with their fingerbones left digging into the sand as they tried to claw their way out. At the top of the burial are two men who were buried lavishly, with one sporting a 5cm-thick blanket of 20,000 shell beads. Cahokia had become unequal and centralized, with a priestly ruling class who used human sacrifice to legitimize their reign. It was on course to become the first state of North America centuries before Europeans would arrive.6

A few decades later, the first signs of instability emerged. A farming complex supplying the city with grain was abandoned, a palisade was erected around the central settlement, and people began to exit the city. Within fifty years its population had halved. Just over a century after that, the entire site, and the area extending hundreds of kilometres to the south-east of Cahokia – once full of similar pyramid-centred towns – had been abandoned. It became known as ‘the Vacant Quarter’, a vast tract of swampy land that was avoided by the indigenous

people. Remarkably, the Native Americans of the area have no stories or oral traditions about Cahokia. It was as if they had intentionally forgotten it. This pioneering civilization-building project was over and would never be resurrected.7

Over 8,000 kilometres away, across the Atlantic, lies the city of Rome. It was once the beating heart of Europe’s largest, most enduring empire. While relatively few know of or visit the ruins of Cahokia, millions flock to see the remains of Rome: the stone and marble skeletons of the Forum and the Colosseum. Rome collapsed, the western half of the empire fragmented, and the population of the city shrank from around 1 million people to 30,000. Unlike Cahokia, Rome was never entirely abandoned. It remains a thriving metropolis of 2.8 million people. And unlike Cahokia, the legacy of Rome would be kept alive by dozens of later kingdoms and empires, including the British. Cahokia’s collapse was terminal, while the city of Rome, its culture and institutions, and the eastern half of its empire headquartered in Constantinople (now modern-day Istanbul) lived on.

Both Rome and Cahokia collapsed. How they fell and the legacy they left varies dramatically. Rome was revered, while Cahokia was left as a bad memory to rot in the swamps of the Mississippi.

To understand the similarities and differences of Rome and Cahokia we need to unravel some of the biggest questions of history. Why did people build these states and civilizations? Why did some of these

introduction: a people’s history of collapse first attempts to build great power structures fall apart? Why was Rome replaced by dozens of imitators while Cahokia’s collapse was seemingly permanent? What did these systems of power mean for the health and wealth of the people living in them? What do these past collapses mean for us in the modern world? Once you pull on the thread of collapse, the entire tapestry of history begins to unravel.

A state is a set of centralized institutions that imposes rules on and extracts resources from a population in a territory, whether that be ancient Egypt or the US today.8 All states throughout history have eventually ended. The average lifespan of a state is 326 years. The largest states – mega-empires covering over a million square kilometres – are more fragile, lasting on average just 155 years. But these averages obscure a staggering range, from the fleeting four-year reign of the Later Han Dynasty in China to the Byzantine Empire of the Mediterranean, which lasted over 1,000 years. While all states have ended, most did not end in societal collapse. Societal collapse is a rarer phenomenon. A phenomenon that afflicts not only states but also broader power structures. Structures that many would call ‘civilization’.9

When most people speak of civilization they are referring to a few basic ingredients: hierarchy (government, bureaucracy), the capture and use of great amounts of energy (agriculture and monuments), and dense populations living in close quarters (cities and urbanism). Collapse involves a rapid and enduring loss of each of these ingredients of civilization.

Yet civilization seems to be a wholly inappropriate term for what we see in Cahokia and Rome. It is derived from the Latin civilitas, which implies restraint, moderation, and good political conduct. Slavery, war, patriarchy, sacrificing teenage girls as the priests of Cahokia did, punishing slaves with crucifixion as in Rome, or dropping atomic bombs on cities as the US did less than a century ago, are not what most of us would consider civilized conduct. Orchestrating mass sacrifices or building bombs that vaporize cities does not require altruism, civility, or democracy. It requires top-down obedience enforced through the threat of violence.

While the term ‘civilization’ is still commonly used, scholars have

introduction: a people’s history of collapse

always struggled to agree on a sensible definition. Some suggestions include an advanced culture (an idea as vague as it is prejudiced against indigenous peoples), or a random checklist of factors such as writing (which neither Cahokia nor the Incan Empire had) and long-distance trade (which essentially all hunter-gatherers conducted). The problem is that most of us are uncomfortable in recognizing the most common element of civilization: rule through domination.

A more apt label for these systems of violence is ‘Goliath’. A Goliath is a collection of hierarchies in which some individuals dominate others to control energy and labour. Goliath refers to a figure from the Old Testament (1 Samuel 17), a towering Bronze Age warrior who tormented the Israelites. Despite his size he was eventually brought down by David, the future King of Israel, who slung one smooth stone directly between his eyes. Similarly, Goliath societies began in the Bronze Age, are imposing in size, rely on violence, and can often be surprisingly fragile.

It was Goliath, not civilizations, that we saw arise in places such as Egypt, China, and Cahokia thousands of years ago. ‘Goliath’ is a far more useful term since it pinpoints what exactly changed in the lands around the Nile, the Yellow River Valley, and the Mississippi. It was a move towards human societies organizing, like many of our chimp cousins do, as a dominance hierarchy. That is, a social-ranking system in which one group or individual is placed above others owing to their ability to impose penalties, including violence. It was the emergence of Goliath.

A Goliath is not just a state. While the Roman Empire was the political heart of the Roman Goliath, there were other hierarchies that preceded it: rich and poor, master and slave, man and woman. A Goliath is a collection of dominance hierarchies organized primarily through authority and violence.

We can use the term ‘Goliath’ in a similar way to civilization. We use civilization to refer both to a general way of organizing society and to specific societies. We speak of ‘the rise of civilization’, or of the ‘global civilization’ of today, yet we also refer to specific civilizations, such as China and Egypt. I’ll be using Goliath in a similar manner. Goliath can mean a general template of organizing society into dominance hierarchies that control people and energy. It can also mean a specific set of dominance hierarchies that often coincide with an empire, such as Rome or China.

Goliaths contain the seeds of their own demise: they are cursed. This is why they have collapsed repeatedly throughout history. Sometimes it is not just a single Goliath that is toppled, but an entire group of them. Approximately three millennia ago, the Mediterranean and Near East were ruled by a network of Bronze Age empires and states. This Late Bronze Age world-system (around 1700–1200 bce ) included the Egyptians, the Mycenaeans in ancient Greece, the Minoans in Crete, and the Assyrians and Babylonians of Mesopotamia. In about 1200 bce this entire system began to unravel.

Around a millennium later, Europe and Asia were dominated by two empires: the Roman Empire in western Europe and the Han Dynasty in China. Each at their peak ruled over some 5–6 million square kilometres of land and 60–70 million people.10

Collapses can be abrupt and unforeseen. The Han faced a small popular uprising that snowballed into the capture of the capital and the end of their dynasty within five years. It took under a century for Rome to go from rule by a single emperor to being a fractured chessboard of competing kingdoms. The fall of the Bronze Age system also took under a hundred years to unfold. Even the most entrenched power structures can be torn apart quickly and unpredictably.

As far as we can tell, no one living at the time anticipated the demise of these empires. Apart from individual disasters, famines, and sacked cities, they likely did not know they were living through a collapse. While a historian may see collapse as a graph of falling population or territory, the first-hand experience is far different. People living through collapse tasted the fear on their tongue while fleeing a city, they felt the heady rush of anger while raiding a granary, and they heard the screams of conflict coming closer. But we can see clearly only when looking back. Collapse may be invisible until after it has occurred. We may be today living through a collapse that is for now slow and imperceptible.

Gazing up at the faded marble columns of Rome or the abandoned granite bones of Machu Picchu often brings a sense of tragic inevitability. A reminder that death comes not just for every individual, but also for every great power structure. Percy Shelley caught that feeling in his sonnet ‘Ozymandias’:

And on the pedestal, these words appear: ‘My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings,

introduction: a people’s history of collapse

Look on my Works ye Mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

Both Ozymandias and real-world examples, such as ancient Rome, evoke a certain ominous uncertainty. Will we face the same fate? Collapse is the spectre that haunts the victors of history.

Collapses throughout history can offer an insight into how and why different power structures unravel, and whether there are any patterns across the millennia. History is a vast database we can learn from, but it must be done soberly. Bear in mind that Shelley’s Ozymandias was modelled on the Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses II (Ozymandias was the Greek version of his name) and it was not a lament for pharaohs or for lost civilizations. Shelley was a staunch believer in republican rule, and the poem was a reminder about the ephemeral nature of tyrants such as Ramesses II .

Historical collapses are neither uniform nor apocalyptic. Many historians and archaeologists now prefer to speak of ‘transformation’ rather than collapse. While some were quick, others were protracted, taking entire centuries to play out. Cahokia lost half its population in half a century, while the fall of the Western Roman Empire took multiple generations. The effects also varied depending on who and where you were. A woman born in Roman Britain in 360 ce could have grown up in a prosperous market town using currency, speaking Latin, seeing columns of Roman soldiers, and glimpsing the bathhouses of the elite. If she lived to sixty, she would have inhabited a Britain with no large towns, no currency, no Roman soldiers or administrators, abandoned bathhouses and monuments, and surrounded by pagan immigrants who didn’t speak a word of Latin. By contrast, an aristocrat in southern France during the same period would have experienced little change, apart from who they paid their taxes to. To a historian, the fall of Rome may look like an obvious event in global history. To a peasant in Spain, it may have barely been perceptible. Collapse is partly in the eye of the beholder.11

The people and culture of collapsed states often persist after the fall. The language, customs, and culture of Rome lived on through new Germanic rulers, and the empire itself persisted for another millennium through the Eastern Roman Empire. The US Senate was inspired

introduction: a people’s history of collapse by Rome, and the Roman language of Latin is still used in institutions today. The Incan language of Quechua is still spoken by around 10 million people today in Peru and surrounding areas. Much of the Mississippian culture that Cahokia pioneered lived on in future Native American communities for centuries, even if the experiment with cities and rulers was forgotten.12 Collapse reveals the fragility of empires, but also the resilience of culture and communities. Collapse doesn’t just change across space, but also over time. And the future of collapse looks far grimmer than the past.

We live in a uniquely dangerous time. Our world is scarred by a pandemic, beset by unprecedented global heating, riven by inequality, dizzied by rapid technological change, and living under the shadow of around 10,000 stockpiled nuclear warheads. Since the invention of the atom bomb the world has come frighteningly close to nuclear war at least a dozen times. The climate change we face is an order of magnitude (ten- fold) faster than the heating that triggered the world’s greatest mass extinction event, the Great Permian Dying, which wiped away 80– 90 per cent of life on earth 252 million years ago. Viruses can now spread at the speed of a jet plane, and computer viruses at the speed of an internet connection. 13

The better-known and more deeply studied threats of nuclear war and climate change are joined by new, more hypothetical technological terrors. In 2023, hundreds of AI scientists and other luminaries (strangely including the CEO s of the main companies building these new AI systems, such as Sam Altman of OpenAI and Demis Hassabis of Google DeepMind) released a statement warning against the risk of human extinction from AI . They fear that an uncontrolled, ultra-intelligent machine whose interests are not aligned with those of humanity (or at least most of us) will either destroy or enslave us. Other scholars, including biological scientists, have warned of advances in bioengineering that could create doomsday diseases – far more contagious and deadly than anything that has ever existed. And those are just the present threats. Who knows what new hazards rapid technological change

introduction: a people’s history of collapse

could conjure in the coming decades. The confluence of these different threats has led some to call our current predicament the ‘metacrisis’, ‘the precipice’, or a ‘global polycrisis’.14

Such apocalyptic angst is not new. Every age has its doomsayers and extinction panics. In the 1920s Winston Churchill warned that humankind was in the unprecedented situation of being able to ‘unfailingly accomplish its own extermination’ in the morbidly titled essay ‘Shall We All Commit Suicide?’ The Czech play R.U.R. (which coined the term ‘robot’, derived from the Slavonic robota, meaning servitude or forced labour) told the story of an uprising of intelligent machines that wiped out their human masters. This occurred in the 1920s, a time still reeling from a global pandemic, the First World War, and rapid industrialization. This doesn’t mean that either current concerns, or those from a century ago, are invalid. It means that we need a reliable way to put the current threats we face into perspective.15

The history of collapse is the most relevant historical phenomenon we can learn from. The present is an extension of the past. The past can tell us how catastrophes have unfolded, how people have proved resilient to them, and why we find ourselves in our own acutely dangerous predicament. Looking at collapse also forces us to confront how societies can destroy each other, as well as produce threats that undo themselves. Collapse isn’t just about how great power structures die, but also about how they kill.16

History can also help us understand the origins of the risk we are facing today. Studies of current global risk tend to become a checklist of different threats: nuclear weapons, climate change, pandemics, and AI . Focusing on each in isolation and looking for technical solutions – such as building benevolent, controllable AI systems – is useful yet short-termist. In 1950 there was only one well-known global risk: nuclear weapons. Diplomatic efforts in the 1980s to reduce nuclear stockpiles by around 80 per cent were welcome, yet they haven’t stopped the world from spiralling into new arms races with algorithms or killer drones, or stockpiles mushrooming again. If we don’t find a way to address the underlying drivers of arms races, then we are doomed in the long term. We need to reverse the root causes of global risk, not just build new technology to cope with the symptoms. Competing companies and countries didn’t just appear overnight;

introduction: a people’s history of collapse

they have a history that can be traced back to human psychology. Fundamental psychological factors and the environmental changes that allowed them to shape the world are the root causes.17 Excavating these root causes can help us determine what we can do next to safely navigate the coming decades and centuries. This excavation of root causes will take us all the way back to 300,000 years ago, when we first developed as a species.

Yet while a future clouded by threats such as nuclear weapons, climate change, and uncontrolled technological change may seem dire, collapse has not always been a bad thing. Throughout history it has been a blessing for many.

Somalia is often used as an example of a modern-day collapse. In 1991, the small sub-Saharan African country fell into civil war. It had been ruled by the brutal dictator Mohamed Siad Barre since a bloodless coup in 1969 put him in power. Armed rebel groups began to surface in the 1980s, before overthrowing the Barre regime. Centralized government was lost, a power vacuum opened, and Somalia became what many would call a ‘failed state’, or even a collapsed one.

But the loss of the Somali state was a blessing for its citizens. A decade later almost every indicator of welfare and development had improved compared to life under the Barre regime. The number of mothers dying during childbirth had decreased by 30 per cent, infant mortality had been reduced by 24 per cent, and extreme poverty had dropped by almost 20 per cent.

Many difficult-to-measure aspects of life also flourished. Under the Barre regime, media was censored, foreign travel restricted, and many forms of free speech (including ‘gossip’) and free association could be punished by death. After the state collapsed, people spoke more openly and moved freely across borders, while numerous media outlets thrived.

Yet these advances cannot be explained purely by the collapse of the brutal Barre government. Somalis’ lives improved in most development indicators even relative to their more stable neighbours in

introduction: a people’s history of collapse

Kenya, Djibouti, and Ethiopia. The only areas of life that got worse were school enrolment and adult literacy, mainly because Western donors withdrew their aid from education programmes. Local militias and governments proved to be more responsive and less extractive than the UN -recognized (and US -backed) reign of Barre. Somalia was better off stateless.18

Somalia’s experience is not unique.19 Many historical cases of collapse may have been a net benefit for many citizens. This should not be too surprising: most states of the past were predatory constructs not dissimilar to Barre’s government.

Despite their splendid ruins, we need to keep in mind the ugly reality of past empires. Rome was an autocratic machine for turning grain into swords. Between 410 and 101 bce the Roman Republic was at war for well over 90 per cent of the time.20 The Roman Empire was the largest slave system ever to have existed, enslaving around 100–200 million people during its reign.21 The Incan Empire was an ethnic pyramid scheme with the ruling Sapa Inca regularly and forcibly displacing hundreds of thousands of people (perhaps up to a third of the empire’s population).22 The different Egyptian kingdoms were national economies organized around a royal burial cult. Much of the workforce was mobilized to build grand cemetery monuments, such as pyramids, to ensure a few leaders’ safe passage into the afterlife. Today, many look at the Great Wall of China as an impressive achievement, a wonder of the world. It’s easy to forget that it was built by prisoners and slave labour, and was intended not just to keep mounted raiders out but to keep citizens in.23

Most empires strove to be endless. The poet Virgil wrote of how the god Jupiter gifted to Romulus, the founder of Rome, an ‘empire without end’. The Nazi regime dreamed of a thousand-year Reich. We should be grateful that such quests for imperial immortality have been repeatedly unsuccessful.

The collapse of a Goliath is not always a largely beneficial affair, as it was with Somalia. It can involve mass displacement, the breakdown of long-distance trade and communication, an end to government services, increased violence, the abandonment of writing and loss of some technologies, and large-scale loss of life. The more typical view of collapse as a historical tragedy is not entirely unwarranted. Collapse is a process that has costs and benefits, winners and losers.

This more complicated picture is often missing in popular depictions of collapse. The experience of Somalia and the blessings of collapse may seem unexpected because the entire idea of collapse is shrouded in myth. It is rooted in deep beliefs about human nature and our apparent need for hierarchy. The most popular image of collapse is that, in the absence of a powerful authority, chaos and disorder reign; people turn to violence in a panicked scramble for resources. Hence, the misguided doomsday ‘prepper’ strategy of gathering guns, ammunition, and tinned foods into remote bunkers. Such myths inform how we think about history. It’s common to envision the past as a series of rises into golden ages during the peak of an empire and falls into post-collapse dark ages. These stories are the hallmarks of disaster movies, fictional post-apocalyptic stories, and bestselling non-fiction books. And these stories persist because the history we have is, of course, not an objective account of the past. It was written on parchment and engraved in stone by the conquerors and slave-owners of the past.

‘The whole of Upper Egypt died of hunger and each individual had reached such a state of hunger that he ate his own children.’ This inscription comes from the autobiography of Ankhtifi, a southern provincial governor of Egypt during the end of the Old Egyptian Kingdom c. 2181–2055 bce . The story etched into his tomb depicts an almost cosmic breakdown of law and order.

Ankhtifi was not alone in describing the loss of the Old Egyptian Kingdom as a tragedy. The Admonitions of Ipuwer, a collection of poems written on papyrus scrolls decades later, also paints an ugly picture. It is a typical example of what historians call ‘lamentation literature’, which gazes mournfully back at a fallen empire and lists a series of evils that befell it, ranging from civil war to famine. The Admonitions of Ipuwer described what is known in Egyptian history as the ‘first intermediate period’, or what most of us know as a dark age.24

Yet the fall of the Old Egyptian Kingdom, as told through Ankhtifi’s autobiography, was deceptive. It seems that there was a drought, but there is little evidence of mass death, starvation, or cannibalism

introduction: a people’s history of collapse as reported in his inscription. The pharaoh lost power, and there does appear to have been increased conflict, but it was not a complete catastrophe. Instead, non-elite tombs became richer and more common. Grave goods, monuments, and amuletic symbols that had previously been used only by an elite became more widely available. Egyptologists refer to it as a ‘democratization of religion’. Government decentralized to provincial levels. Nobles became more impoverished, while commoners appear to have become richer and more socially mobile.25

The Admonitions of Ipuwer confirms this. Most of the text is a tirade against the empowerment of the peasants and an inversion of the social order:

The corn of Egypt is common property . . . Indeed, the poor man has attained to the state of the Nine Gods, he who could not make a sarcophagus for himself is now the possessor of a tomb . . . Behold, noble ladies are now on rafts, and magnates are in the labour establishment, while he who could not sleep even on walls is now the possessor of a bed.

Servants spoke freely. The nobles lamented. And the poor rejoiced.26

The horror of servants gaining free speech and the collective ownership of collectively produced food is not usually what comes to mind when one thinks of collapse. Though clearly it was for the writers of the Admonitions of Ipuwer. The poems expend far more energy fretting about this reversal of fortunes than on war and starvation.

Many people benefited from the fall of the pharaoh and the Old Egyptian Kingdom. As a nomarch (provincial governor) of Upper Egypt, Ankhtifi himself may have been a beneficiary. When the authority of the pharaoh disappeared, nomarchs took on more power. Ankhtifi was buried in a lavishly decorated tomb, which portrays him as a great saviour during this period of instability. His autobiography was mainly an exercise in self-aggrandizement.

Ankhtifi and lamentation literature more generally are emblematic of a key problem: the 1 per cent view of history. Most of the archaeological evidence we have – palaces, pyramids, and written records – is all from the smallest, wealthiest class.

We judge historical collapse based on what archaeologists have dug up. The easiest remains to find are monumental structures such as

introduction: a people’s history of collapse palaces, temples, and fortresses, as well as grand burials with a few prized individuals buried with their weapons and jewellery. In short, the more stuff you produced and left behind, the larger your entry in the archaeological record. Unfortunately, the vast majority of people in the past left faint, biodegradable fingerprints. For over 99 per cent of humanity’s time on earth people have not lived in cities but as foragers or as peasant farmers.27 Even at the height of the Roman Empire around 90 per cent of the population were rural farmers. And yet, we know most about what happened to a few palaces and city centres, not the thousands of farms and villages.28

This leads to problems when studying ancient collapses. Did the fall of the Classic Lowland Maya and the Western Roman Empire lead to large-scale losses of life or mass displacement? People who leave cities and move back to the land leave behind fewer traces. They become archaeologically invisible. This migration from urban to rural areas can make it difficult to tell whether much of the populace perished or simply moved away. It can also make it difficult to know how their lifestyles changed, giving us a skewed picture of how collapse unfolded.29

The elite bias is most evident in writing. Writing and other forms of documentation were an exclusive art for government bureaucrats and aristocratic representatives up until the invention of the printing press. The earliest forms of fully fledged writing, dating back to around 3000 bce in Mesopotamia, were not letters or poems but tax records, administrative documents, and government propaganda. The first writer was probably an accountant.

Writing, for most of human history, has not been a widespread practice. Most people in the world couldn’t read or write until the nineteenth or twentieth century. This was because the average individual faced numerous impediments to literacy. Writing materials were expensive and hard to procure, writing is often difficult to learn (it takes years of training for children even today), there were frequently restrictions (particularly for women) on who could learn, and there was usually little to no benefit if you were a farmer or peasant. Before the advent of the printing press, writing was dominated by a small, select number of scribes employed by rulers and the richest families.30

Records are also mainly penned by the victors of history. We have a

introduction: a people’s history of collapse

deep insight into the lives of the Roman elite, but little knowledge of the non-state peoples who covered most of the world.31

Most of our sources tend to show collapse through the eyes of its greatest victims: enriched elites. ‘Elite’ does not mean individuals who are particularly skilled or high-performing, but rather the top 1–10 per cent of decision-makers and wealth-holders in a society. We need to go beyond the elite view and provide a more realistic analysis of history and collapse. What did it mean for the health and wealth of the slaves, peasants, and farmers?32 We need something closer to a people’s history of collapse.

A common question is whether the history of crisis and collapse in agricultural empires can provide lessons for the modern, globalized, and industrialized world. While many factors distinguish the modern world from ancient history, they don’t make collapse less relevant. In each of the key dimensions of collapse – energy capture, population density, and hierarchy – the modern world is simply an intensification of the past. The study of collapse is more relevant than ever.

Globalized society is dependent on unfathomable amounts of energy. In just the last 200 years energy consumption has risen ten-fold.33 The surge in energy use can also be seen in how much energy is ‘captured’ per person. That is, how much energy – calculated in terms of calories – is taken from the environment and used by humans, whether that be for food, heating, electricity, or construction. The average ice-age hunter-gatherer in Europe would have captured about 4,000 calories per day. The average European now uses around 230,000 calories.34

While fossil fuels are a new source of energy, we are still dependent on the same few types of grains to feed almost the entire world. About two-thirds of the world’s food energy intake comes from three staple grasses: wheat, rice, and maize. Wheat alone provides about one-fifth of global dietary calories. We are still agrarian in our tastes, even if we now rely on fossil-fuel-devouring production.35

Collapse tended to hit urban areas far harder than rural ones. Today we also live in an unprecedentedly urban age. For most of

introduction: a people’s history of collapse

human history, the majority of humanity has lived in rural settings. It was not until 2007–8 that over half of the global population resided in urban areas. By 2050, around two-thirds of the global population (6 billion) are expected to live in urban areas.36

Societal collapse is mainly about the fall of great power structures. The world is dominated not just by cities, but by hierarchy. It is covered by a single political type: political states. If you are reading this, you are almost certainly a citizen of one of the 205 states that cover the world. Modern nation-states have their roots in far more ancient institutions. The first state was the First Dynasty of Egypt (around 3100 bce ). Now, almost every square inch of habitable land is under sovereign rule. Previously, large states shaped how people and disease spilled across the land. Now, they can unleash nuclear war across continents and change the global climate.

Perhaps most importantly, the basic human psychology that has driven war and collapse throughout human history has not changed. Modern technology may seem like a saviour, but it also brings unprecedented threats, whether it be nuclear weapons or fossil-fuel-driven climate disruption. Remember that it was innovations in gunpowder, steel, and navigation that provided the basis for the transatlantic slave trade.

We’ll examine dozens of cases of collapse, from the first cities to modern state failure, as well as a novel database of over 300 states spanning the past 5,000 years. This is the Mortality of States (MOROS ) dataset, named after the Greek god of doom. It also includes the leading work of others, such as the Seshat Global History Databank (named after the Egyptian goddess of knowledge), the world’s largest dataset on global history, maintained by a group of archaeologists, historians, and others.

This broad-sweeping approach diverges from how others have analysed collapse. Most popular books on collapse have tended to focus on a few select examples. Jared Diamond’s well-known Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Survive covers five historical cases: the Pitcairn and Henderson Islands, the Rapa Nui, the Greenland Norse,

introduction: a people’s history of collapse the Anasazi, and the Lowland Maya. Four of these are small, isolated communities and three were islands. The Lowland Maya were a collection of competing city-states with a common culture living in a unique environment with a tropical climate and a fragile topsoil. While these are helpful as isolated examples, they are not necessarily the most instructive cases for the globalized, interconnected world of the twenty-first century.

Eric Cline’s magisterial 1177 b .c .: The Year Civilization Collapsed surveys a more relevant case: the Late Bronze Age (1200–1150). The Late Bronze Age was, in many ways, a Mediterranean microcosm of our contemporary world: a group of diverse empires, kingdoms, and cities with close political and trade ties. The splintering of the Bronze Age world is informative, but there are still thousands of years and hundreds of other cases that need to be considered. We can’t discern any general patterns, and absorb their lessons, without taking a broader view across time and space, one that reaches back to our very beginning as a species.37 Part One examines collapse from the dawn of our species to the emergence of the first states. Part Two surveys the rise and fall of empires over the past five millennia. Part Three concludes by looking at the future and the prospect of a modern global societal collapse.

Collapsing Back into Human Nature – Fluid Civilizations – Neither Nasty nor Brutish – The Myth of Mass Panic – Egalitarian Origins – Killing in the Name of Equality – Status Competition

Our views of human nature and collapse have been profoundly shaped by one seventeenth-century philosopher: Thomas Hobbes. Hobbes’s mother reportedly entered labour in 1588 when she heard that a Spanish armada was approaching the English coast. Later Hobbes remarked that ‘my mother gave birth to twins: myself and fear’, and Hobbes’s life was scarred with fear and insecurity. He lived through repeated periods of political turmoil, including the English Civil War, during which he was exiled for eleven years to France. His pessimistic philosophy about human nature reflected the chaotic life he endured.

Hobbes’s most lasting idea was the ‘social contract’: a political bargain in which citizens give up some liberty to a supreme ruler who can provide them with security. The monarch protects the people from each other. Hobbes saw ‘the state of nature’ – life without a central political authority – as one of perpetual war of all against all. In a much-quoted passage Hobbes decries how this ‘state of nature’ would entail no navigation, no industry, and ‘no commodious building; no instruments of moving, and removing, such things as require much force; no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of

dawns and ends all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.’ Without government, chaos would rule instead.1

Hobbes had no access to archaeological finds, psychological experiments, or anthropological ethnographies to verify these theories. So instead, he constructed a list of assumptions about human psychology and used them to paint a dark picture of life without rulers. People lived in the deadly and destitute ‘state of nature’ until they managed to agree on a social contract and appoint a sovereign ruler to keep them from each other’s throats.

His views are also representative of why so many people fear collapse: once the social contract breaks, the state of nature re-emerges with dire consequences. This bleak vision is known as veneer theory: ‘a thin veneer hiding an otherwise selfish and brutish nature’. Once civilization is peeled away, chaos spreads like brushfire. Whether it be in post-apocalyptic fiction, disaster movies, or popular history books, collapse is often portrayed as a Hobbesian nightmare.2

None of this originated with Hobbes. The story of kings rising up to tame a primordial chaos is thousands of years old. One of the foundational documents of Hinduism, the Mahabharata of the first millennium bce , has a warrior reflect, ‘We have learned that peoples without kings have vanished in the past, devouring each other, the way fishes in the water eat the smaller ones.’ The Buddhist scriptures known as the Dīgha Nikāya recount how during a mythical time of discord and theft a group of people went to the one ‘who was most handsome and good-looking, most charismatic, and with the greatest authority’ and gifted them the powers of a ruler such as the ability to accuse and banish others. In exchange, the people offered a portion of rice to their new leader: an early, edible tax. Similar fables of mutual dependence between the rabble and a necessary ruler are retold in literature throughout the ages, from Aristotle’s writings about an ‘elected dictator’ through to Zhou-era songs in China. Hobbes merely gave the best-known philosophical articulation to a story that has been told for thousands of years.3

Hobbes’s ideas weren’t even novel for his own time. They reflected the Puritan Christian belief that the natural state of humanity was one of perpetual war against each other, God, and all creation. It was only through God’s grace that they could be peaceful with each other

and eventually reach heaven. Hobbes’s contemporary John Milton claimed that states were formed ‘to avoid the discord and violence that sprang from Adam’s transgression’. Earlier leaders of the Church had similarly used the supposed sinfulness of man since the fall of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden to justify the establishment of governments. Church and state became an extension of the heavenly hierarchy on earth. Hobbes borrowed an idea from theology and applied it to political philosophy.4

The Hobbesian worldview is closely entwined with another collapse-related stereotype: mass panic. The story goes that as soon as a crisis hits, whether it be a war, pandemic, earthquake, volcanic eruption, asteroid strike, or a plague of zombies, people will react with a selfish and irrational rush for resources. This is related to what some call ‘civil disorder’. Disasters bring out the worst in people, leading to rioting, looting, robbery, and violence.5 Scenes of mass panic can be seen in almost every disaster film, including Independence Day, Armageddon, and Contagion. One survey of 448 UK citizens and emergency-response professionals suggests that this assumption about mass discord is common.6 The Hobbesian nightmare of panic, disorder, and bloodshed colours how we think people act in crises.

This Hobbesian nightmare of violence and mass panic is a theory not just about life outside government but also about human nature. Hobbes built his image of humanity on a mythical ‘state of nature’, a time before government. This is a kind of fictional, primordial situation when true human nature shone through. There is, of course, a non-fictional parallel we can draw on, the period from around 300,000 years ago when humans evolved in a world without governments or great power structures. This is commonly called the ‘Palaeolithic’ (see Table 1; I’ll be using ‘Palaeolithic’ or ‘ice age’ throughout the rest of the book), a time before the unusually warm and stable climate known as the ‘Holocene’ began 12,000 years ago. When scholars claim that humans are innately violent or antisocial it is built on how humans evolved during this stateless time. The Palaeolithic can indeed help us see our evolutionary inclinations (what is usually referred to as human nature). That is, the innate behaviours we tend to adopt unless culture strongly compels us not to.7

Table 1: Human epochs (BP = Before Present)

Everyone has assumptions about our evolutionary inclinations, Hobbesian or otherwise. With so many blank pieces in the puzzle of history, we fall back on our view of innate human drives to fill in the gaps. Even the most careful historian will still end up stitching together any loose threads using their own unspoken assumptions about humanity. Rather than silent assumptions or old philosophers, we are better off relying on evolutionary biology, studies of modern foragers, and the thousands of archaeological sites and artefacts from the Palaeolithic to construct a picture of how human societies organized during the ice age.8 That can give us an idea of our evolutionary inclinations: the behaviours that shape the causes of collapse and our response to disaster. The picture that is emerging is far more interesting, and hopeful, than a Hobbesian chaos.

The Palaeolithic was a challenging time to survive. The world went through a period of glacial cycles. During the coldest periods global temperatures were around 5°C lower than today and glaciers covered up to 30 per cent of the earth’s surface. This would have made prolonged, intensive agriculture impossible.9 Africa was far drier than today and littered with around eighty-six active volcanoes.10

During this time our ancestors wandered out of Africa into the wider world in sociable, well-connected, egalitarian, nomadic bands. This was no random choice of social structure: it was a winning strategy to survive the ice age.11

These egalitarian bands were cosmopolitan and varied in size. The

average was likely to have been small, around twenty to forty individuals, but may have ranged up to 150–200 people. They were not restricted to family members. Recent genetic evidence suggests that in many hunter-gatherer groups less than 10 per cent of individuals in a band were closely related.12 Each group drew on a wider pool of non-genetically close individuals, often from far-flung territories, who may not have even spoken the same mother tongue.13 These unrelated friends are vital. Studies of the Agta hunter-gatherers of the Philippines and the Bayaka of central Africa show that some types of knowledge, such as information about plants, are more commonly shared among close friends than family members. When it comes to keeping groups together and progressing culture, friendship is as thick as blood.14

This almost certainly held true for our ice-age ancestors. Without webs of friendships, we also wouldn’t have seen new stone tools and rituals develop and spread. Without intermarriage across groups to encourage genetic diversity, we would have fallen prey to inbreeding and other genetic problems.

Our Palaeolithic ancestors were intensely social. Not just among their bands, but also across far broader networks. For a long time, people believed that close human connections had a ceiling of roughly 150 people. This is called Dunbar’s number and crops up in areas ranging from the size of church congregations to Facebook groups.15 Dunbar estimated this by looking at the size of the neocortex (a part of the brain responsible for higher cognitive functions) of primates relative to the size of their groups and then extrapolating this to humans. Whether this extends to humans is questionable, and numerous studies using updated data and multiple methods have tended to come up with larger numbers across a wider range, the estimates varying from 2 to 520. There is no easy, clear ceiling to our social connections.16 It is also a little misleading. While we might have a flexible cap on how many people we can closely know at a given time, this doesn’t stop us from frequently changing and updating our connections to create a far larger web. Hunter-gatherer groups of today have fluid, flexible social networks with thousands of connections. Individuals are constantly mobile and moving between groups, picking up new friends, family, and sometimes partners along the way. They are more like a city dweller than an isolated family in the countryside. There is no easily numbered ceiling on human social group size.17

Our Palaeolithic predecessors were never antisocial loners focused solely on their families and distrustful of strangers. They were welltravelled, well-connected socialites who usually lived in vast societies. We inherited their innate sociability. There is a good reason why solitary confinement is the worst punishment that can be handed out, even in prisons. Our love of other people led to vast webs of shared culture and trade.

Our ancestors constructed a regional microcosm of the current globalized world. They were a people on the move who traded raw materials and shell beads over distances of about 200 kilometres per year (as egalitarian hunter-gatherers do today). Many of these networks are truly ancient. Obsidian – a black, volcanic glass that can be used as a tool, decoration, or blade – was traded over 160 kilometres around 200,000 years ago while ostrich eggs were exchanged across eastern and southern Africa at least 50,000 years ago. Much of this was built on gift-giving and reciprocity: the impulse to give back whenever we receive, whether that be gifts, help, or favours.18

These trade networks could overlap to spin webs of shared culture and technology. Across the world we see that Palaeolithic foragers crafted large, continent-spanning zones of common tools, and rituals. We may have the African Union today, but 120,000 years ago huntergatherers were exchanging genes, tools and musical instruments from one side of the continent to the other.19 Around 43,000–28,000 years ago, across Europe and Asia, from Siberia to France, people left similarly crafted tools, weapons, figurines, and even artwork in what archaeologists have called the ‘Aurignacian’ cultural tradition. It was a zone of common culture that surpassed the European Union in size. Similarly, people across North America 13,050–12,750 years ago all used the same ‘Clovis’ tipped projectiles, stone blades, bone rods, and other tools. Mobility was the connective tissue of these giant cultural bodies.20 As the Cambridge anthropologist Cecilia Padilla-Iglesias observed, ‘movement was never just a means of finding food, but of finding one another across entire continents’.21 Think of these as fluid civilizations: networks of cooperation built on foot by people moving and intermixing (Figure 2).22

The lives of those within these fluid civilizations were not poor, unhealthy, or doomed to be ‘short’ and ‘nasty’. Ice-age foragers were taller and in better health than the farmers who took over the world.

Low to Mid Density

High Density

Low Density

Mid Density

High Density

Excavated Archaeological Sites

Top is the Aurignacian Culture (41,000–26,000 bce ) and bottom is the Clovis Culture (around 11,000–10,800 bce ). For both, heavier shading shows key areas of dense and intense occupation, while lighter shading shows the general reach of the cultural zone.

Today, foragers are less likely to face famine than non-industrial farmers.23 The modern forager-horticulturalist Tsimané of the Bolivian Amazon have the lowest rate of atherosclerosis (hardening and thickening of the arteries, a key precursor to stroke and heart disease) of any recorded group. The Tsimané also experience less brain atrophy than their industrial counterparts. They lose 70 per cent less brain volume as they age than their peers in Europe and the US . 24 The Tsimané are not an outlier. Reviews of hunter-gatherer populations have found that they have exceptional health, with low rates of obesity, diabetes, cancer, stroke, heart disease, and other cardiovascular and metabolic health problems.25 These findings are even more impressive given that modern foragers are often marginalized groups.26

The working hours of foragers also compare favourably to both agriculturalists and modern workers. One study compared the Agta foragers of the Philippines to an Agta group that had been paid by governments to settle and take up rice farming. The foragers had about ten hours more leisure time per week than their farming neighbours. While estimates vary, most studies suggest that huntergatherers work around forty hours (with a range of approximately twenty to fifty) per week. This ‘work’ includes hunting, fishing, gardening, foraging, cooking, and walking through natural landscapes. Most people would not necessarily consider this work and go hiking or hunting for holidays. Many of these studies also classify walking, childcare, and domestic chores as work. If we applied that same definition to the average American, they would spend around fifty-five to seventy-seven hours a week working.27

There is a vast difference between spending your days following orders in an office or factory, and fishing with friends. Critically, the average person in the world today is also not a middle-class worker in Australia or Norway with paid holiday leave. Instead, they are more like poor farmers or sweatshop workers in India or China.

The lives of both our prehistoric ancestors and non-state foragers were still far from ideal. Roughly a quarter of children died before reaching the age of one, and only half made it to puberty. Literacy was non-existent, and many tasks involved hard labour. There are reasons to pick being a citizen of modern Denmark over being a Palaeolithic forager.

Still, hunter-gatherers who made it past childhood generally led healthy, happy, relatively long, and deeply social lives. A centralized authority was not necessary to ensure coordination or prevent deprivation. Instead, our mobility and sociality allowed us to create great webs of shared culture and technology. All of that would have been difficult if humans had been trapped in a state of perpetual war against each other.

The key to the Hobbesian story about human nature and collapse is violence. Without an overseer, people allegedly turn on each other. An orgy of disorder and bloodshed is not conducive to trade, constructing buildings, or doing anything else that involves cooperation. It is worth pausing here to specify what we mean by violence. In this case we can focus narrowly on direct acts of lethal aggression. This includes both interpersonal violence (between individuals) and warfare (between groups). Just how violent are stateless foragers?28

Foragers without a government in the modern world vary dramatically in their rates of violence. One study across fifteen hunter-gatherer groups found homicide rates per 100,000 person-years of life ranging from 1 (in the Batek of Malaysia) to 1,018 (in the Hiwi of Venezuela and Colombia). In other words, for a population of 100,000, every year there would be one murder among the Batek and 1,018 among the Hiwi. Another found a spectrum from the peaceable Bakairi (of Brazil) who had 0 per cent of deaths from violent causes to the Ache (of Paraguay) who had a chilling 55.5 per cent. We thus have a range from the safest people on earth to people whose daily existence is more dangerous than in most war zones. Rates of violence can also change substantially over time.29

Looking across all modern foragers isn’t always the most reliable method, since these groups have been shaped by their interactions with farmers and colonizers, including invasions and confrontations. These rates of lethal violence among non-state peoples also misleadingly include massacres and murders inflicted by farmers, miners, and other intruders. This makes the high estimates of violence among

foragers entirely misleading. For instance, all the cases of large numbers of Ache being killed (often mistakenly reported as war-deaths) were due to slave-traders and Paraguayan frontiersmen. Similarly, many of the instances of lethal violence among the Hiwi (and all reported war-deaths) were caused by invading ranchers.30 These statistics also include homicides fuelled by alcohol or drugs, which were usually introduced by colonizers. Many of the deaths are better attributed to colonization than to our immutable ancient instincts.31

Rather than just looking at living examples of stateless hunter-gatherers, we can turn to archaeological evidence. In 2013, the anthropologists Jonathan Haas and Matthew Piscitelli of Chicago’s Field Museum conducted the most comprehensive analysis of violence in pre-history. They looked at almost 3,000 skeletons from over 400 sites before 10,000 bce . They concluded that interpersonal violence in the Palaeolithic was rare and warfare absent. Only six sites contained any indications of violence at all. One was a triple burial in the Czech Republic, although none of the skeletons bore any of the telltale signs of a grisly death. Four more sites had one or more individuals with projectile points embedded into their bones. However, these could have been accidents, perhaps a mishap while hunting. The only legitimate site that indisputably shows interpersonal violence is as famous (at least among archaeologists) as it is exceptional: Jebel Sahaba in Sudan. At this site, fifty-eight skeletons were buried, twenty-four of which had signs of violence etched into their remains. Yet the injuries seemed to be repetitive, and some were healed. This may suggest occasional raids and ambushes rather than a single bloody war. The site also dates to 12,000–10,000 bce , at the very end of the Palaeolithic during a time of environmental upheaval when the planet warmed and exited the ice age.32

Another systematic study produced similar results to Haas and Piscitelli: the observed deaths in the archaeological record equate to a 1.3 per cent violent death rate. In other words, about one in every hundred people died due to some form of physical violence, whether that be a hunting accident or interpersonal conflict. This makes the Palaeolithic more or less as peaceful as the modern world. Today, about 0.9 per cent of deaths globally are due to homicides or war. Another 1.3 per cent are today due to suicide, putting total violent deaths at 2.2 per cent.33

These numbers may seem surprising. Many famous accounts

suggest that the Palaeolithic was a war zone with homicide rates of 15–25 per cent. Perhaps the most well-known is Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of Our Nature, which estimates a Palaeolithic violence rate of 15 per cent. These numbers don’t stand up to scrutiny. The anthropologist Brian Ferguson has shredded the list of twenty-one archaeological sites that Pinker draws from: three are duplicates, three have only one case of violent death (no reliable indication of war), and another has no war fatalities at all. Of the remaining twothirds, only one case dates to the Stone Age. The systematic studies of Hass, Piscitelli, and others, which found a much lower rate, are a far better guide to violence before the Holocene.34

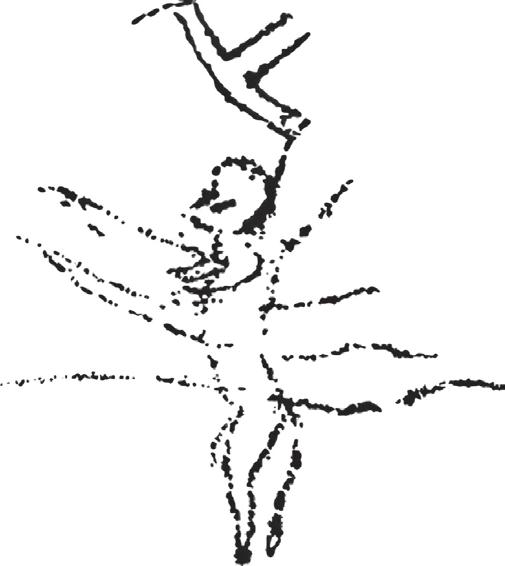

The skeletal record of low rates of violence is reinforced by the history of cave art. Before 8000 BCE , there are thousands of depictions of humans hunting and butchering animals. There are only three caves with art that can be interpreted as depicting human-on-human killing. Cosquer, Cougnac, and Pech Merle in France collectively contain four images that could be construed as a figure punctured with spears. Yet even that reading seems suspect: two of the figures have tails (see Figure 3) and the other two more closely resemble a goat antelope frequently drawn in other caves.35

Phylogenetic evidence (studying the evolutionary relationships between

Figure 3: Human or horse?

The figure on the left is from Cougnac cave and the one on the right is from Pech Merle cave, both in France. Both have been interpreted by some as humans riddled with spears and arrows. Ask yourself, do these look like unfortunate victims of war, or a successfully hunted horse, buffalo, or antelope goat, complete with tail?

species using genetics) can also shed light on our proclivities for both war and peace. One study surveyed the rates of violence within species for 1,024 mammalian species to predict how violent humans should be. Species that are genetically closer to us, such as chimpanzees, should be a better predictor than mammals generally of how murderous humans are. Their analysis suggests that prehistoric hunter-gatherers have an interpersonal kill rate of about 2 per cent, similar to other great apes. In other words, for every hundred ancient foragers, two would have died from a lethal attack from another human. That is hardly evidence of a belligerent nature or of Palaeolithic war. And it is ten times or so lower than the 15–25 per cent kill rates that more pessimistic scholars have claimed. There is also evidence that we are less violent than some of our primate relatives.36

Scholars frequently cite examples of warfare and fighting among chimpanzees as evidence that we are genetically predisposed towards violence. Yet chimps and humans are quite different. Chimpanzees have developed several genetic changes that allow them to endure more pain, heal more rapidly, and stay calm during high levels of stress. These are adaptations to higher levels of interpersonal violence. They were also all genetic changes that appeared to have happened after humans and chimpanzees diverged from a common ancestor.37 This is evidence of our relative peacefulness, not aggression. And those few examples of chimp ‘warfare’? Most of them seem to be caused by human interference, whether that be the destruction of chimpanzee habitats causing territorial conflicts or anthropologists feeding chimps.38 It’s important to bear in mind that chimpanzees are just one of our primate relatives which is often cherry-picked to cast humans in a bloody light. We have other relatives, such as bonobos, among whom violence between groups is virtually absent.

Perhaps the most compelling proof of our relative pacifism comes from our simple reluctance to hurt each other. Interviews with soldiers, examinations of weapons, analysis of combat photos, and re-enactments of battles all suggest that in past conflicts weapons were often unused by well over half the combatants, and that soldiers often misaimed intentionally to avoid hurting their enemies.39

It wasn’t until the Vietnam War that the US developed more immersive training experiences to overcome this squeamishness and brainwash men into being better fighters.40 The truth is that most of us are not

hardwired to hurt or kill each other. We need to be programmed to commit murder.

This doesn’t match the Hobbesian story. If our deep past was marked by persistent battles, then shouldn’t we be aggressive killers? The pacifists and peaceniks would have been killed off before they could reproduce. Soldiers today shouldn’t need so much training and moulding. They certainly shouldn’t be psychologically scarred by being on the battlefield.

This scenario of pre-history as a war zone also doesn’t fit with the presence of fluid civilizations. If there were such high rates of violence, especially between groups, then long-distance trade and constant migration across groups would have been offputtingly risky. No one wants to walk across a war zone. Yet we see ample evidence of trade, intermingling, and the sharing of culture and technologies across vast areas of the world. None of this is to say that there wasn’t competition between groups or that violence didn’t exist in the Palaeolithic. Rather, lethal conflict was muted with a maximum of around two out of every hundred people dying owing to interpersonal violence (if the genetic evidence proves reliable). That makes the Palaeolithic a little safer than the modern world (if we include suicide) and far safer than most other historical periods. Small-scale war may still have existed, but we simply have no evidence for it.41

Palaeolithic violence was probably highly personal. With little inequality, there would have been few material rewards for killing others. One study of 148 deaths in modern nomadic huntergatherers found that 55 per cent were caused by violence between individuals. Two-thirds were due to interfamily disputes, accidents, in-group executions (usually of an aspiring tyrant or violent individual), and sexual jealousy.42 We should take evidence from more recent hunter-gatherers with a dose of scepticism, but in this case it is limited to nomadic groups who have lifestyles and foodgathering strategies similar to those of our Palaeolithic ancestors. It is also simply logical that violence in the Palaeolithic would be similarly personal, given the lack of wealth to fight over. Crimes of passion will be as old as human emotions; war, however, is a modern phenomenon.

At this point a sceptic might still argue that, while we can cooperate, our true violent, disorderly tendencies emerge during a time of

scarcity and crisis. Disasters reveal our true nature. Palaeolithic foragers may overturn Hobbes’s view of human nature in general, but what about during a collapse?

Scholars of modern disasters refer to the idea of ‘mass panic’ as a myth. Groups panicking and devolving into a directionless rabble is ubiquitous in Hollywood films and the warnings of politicians but is rarely spotted among actual crises. Instead, people rapidly self-organize to provide medical care, support, and essential services.43 Fifty years of sociological, psychological, and documentary evidence has converged on this simple yet profound finding. It has been reported in study after study, including earthquakes, hurricanes, terrorist attacks such as 9/11, and the mass bombings of cities.44 The world crumbles away, often revealing the best in us – our cooperative, civil side.45

People not only tend to respond quickly, creating alternative arrangements for services that may have been disrupted, but they also tend to remember these moments of disruption with fondness. They describe a peak experience where the fabric of reality split open and revealed not chaos, but the possibility of a more intimate and meaningful community. Rebecca Solnit explores this beautifully in A Paradise Built in Hell, showing that, whether it be 9/11 or the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, people usually respond with empathy, generosity, and resourcefulness.46

It makes sense when we think of this from an evolutionary perspective. The winning strategy to surviving in the Palaeolithic was to use our mobility, extreme sociality, and broad connections to our advantage during calamity. If there was extreme weather in one area, rather than panic, you could migrate to a set of friends or relatives elsewhere as a social safety net. We still see this among the nomadic Ju/’hoansi of South Africa today. They maintain long-distance gift-giving and sharing relationships (Hxaro exchange partnerships) up to 200 kilometres away as a kind of insurance policy. When disaster strikes, they can rely on these distant friends for shelter, food, and companionship. Many other egalitarian foragers have similar arrangements. This is

logical: individuals who could rely on their social networks during disaster were more likely to survive and pass on their genes (as were their friends whom they would have supported as well).

That same evolutionary logic also applies to groups. If a Palaeolithic group of hunter-gatherers were hit by a drought, a storm, or a volcanic eruption, then responding with panic would have only made things worse. Groups who reacted with disorder would have been less capable of an effective emergency response, such as sharing food and migrating to friends, while those who worked together would have survived and passed their genes and culture on.

The prevalence of cultures of hospitality towards guests may even be a relic of this ancient approach to handling disasters. The Greeks and Romans had the idea of hospitium, the divine duty of the host to help, entertain, and even give gifts to guests. Hospitium was underpinned by cautionary tales of the god Zeus disguising himself as a beggar to punish those who abused their guests and reward the hospitable hosts. The Norse too had an emphasis on guest rites with similar stories of Odin dressing as a traveller to test different households; the Indian Upanishads advise Atithi Devo Bhava: the guest is akin to god. Being kind to visitors and strangers in need is perhaps the lingering memory of how we helped each other through the ice age.

Fluid civilizations may have even been partly driven by this friendly solution to managing disasters. Treating guests with great kindness would have encouraged mobility and sharing, especially when faced with disasters. That, of course, wouldn’t have happened if mass panic had been our automatic response.

It would be strange if people’s response to historical collapse was contrary to both modern behaviour and evolutionary logic. Rather, historians see the same displays of communal resilience and solidarity throughout cases of societal collapse from antiquity to the modern world.47 Collapse is not a matter of reverting to instinctual violence and civil disorder. Whether it be the sack of Rome, or famine in Egypt, or Covid-19, the response of most people is not mass hysteria, selfish struggle, or pervasive conflict. It is instead often fairly egalitarian altruism.

For the vast majority of human history there were no chiefs, commanders, or aristocrats. There were none of the usual signs of disparities in power, whether that be unequally sized dwellings or an individual or group buried with especially extravagant goods. These indicators didn’t unambiguously appear until around 11,000 years ago, once we exited the ice age. Our Palaeolithic ancestors were egalitarian.

Part of this was simply due to the environment they lived in. In a world of volatile weather and scarce resources, being constantly on the move was a necessity. That mobility also meant that few resources could be carried around or hoarded. This prevented the build-up of economic inequality. Human numbers were also incredibly low and widely dispersed. By the Late Palaeolithic, the combined populations of Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia totalled roughly half a million people. That’s about the population of a small city such as Bristol in the UK or Atlanta in the US . It would have been easy to escape anyone who tried to dominate a group.

Yet this egalitarianism was not a passive condition but an active choice. Modern egalitarian foragers have an array of customs and traditions to strictly enforce sharing. The Ju/’hoansi swap arrows before a hunt and it is the original owner of the arrow – not the hunter who fires it – who allocates the meat from a kill. Thus no single hunter is ever able to amass a resource surplus over the rest of the group. Such food sharing is common across egalitarian foragers where any refusal to share food or resources is met with opprobrium (there is evidence of meat sharing from Palaeolithic carcasses too).48 This makes good evolutionary sense: no individual could rely on being the most successful hunter or gatherer every day. Sharing was both an insurance mechanism and a bonding method. That love of sharing is deeply ingrained in us. For most of us, the best activities are ones that are shared, whether food, jokes, beds, or lives.49

Sharing also meant sharing political power. Democracy comes from the Greek words demos (‘people’) and kratos (‘power’). Democracy is people power: how equally shared is the ability to govern and make decisions. It is a spectrum of (more or less) equal and inclusive political practices. Any endeavours that require collective decision-making

can be democratic, whether it be workplaces, families, or organizations. Across the board, hunter-gatherers tended to be deliberative and inclusive, often more so than even modern democracies.50

In many modern forager communities, decisions are made either by individuals or by consensus. Many foragers, from the Huron peoples of North America to foragers in central, southern and eastern Africa, regularly practise small-scale consensus deliberations. There are no permanent chiefs or commanders. When leaders do appear – individuals who are more outspoken, persuasive, or respected and heeded by the community – they are shackled by expectations. They are expected to be modest, generous, and egalitarian, and are kept politically toothless. The anthropologist Robert H. Lowie in his studies of numerous huntergatherer groups across the Americas, such as the Ojibwa, the Dakota, and the Nambikuára, found that chiefs had no power to impose decisions on others. They were more like unpaid facilitators. Again, while we can’t easily extrapolate from present hunter-gatherers to ancient ones, the evidence suggests that a similar model was followed in the Palaeolithic. We have no signs of enduring inequality or hierarchy, and modern nomadic-egalitarian groups who have the lifestyles closest to our deep past are especially democratic.

Today, we often make the mistake of thinking that democracy is a Western invention and simply a form of representative government using elected officials. This is just one recent, elitist model of democracy. It can first be seen in the parliaments of bishops, warrior aristocrats, and the rich organized by Alfonso IX in León, Spain, around 1188 ce to achieve support for increased taxes. Britain later adopted a similar parliamentary system, which it exported throughout the world during colonization.

Democracy goes far deeper than this. It can be direct democracy, like an assembly of citizens collectively deciding on whether to go to war or what to build. We see signs of these in ancient Africa, China, and Mesopotamia. It can be sortition, where citizens are randomly selected to represent their peers. Ancient Athenian democracy (from about 508 until 322 bce ) was a combination of both assemblies of free men and magistrates selected randomly by lottery. The democracy of hunter-gatherers, with major decisions decided on by a group of equals, is even more intensely democratic than the Greek version, which was restricted to free adult men. All evidence suggests that

political power was widely shared in the Palaeolithic and group decisions were made democratically. Democracy is humanity’s default political system.51

When we think of this in terms of power, each form (political, economic, violent, and information) was evenly distributed. Perhaps a particularly skilled shaman or warrior may have temporarily gained an advantage over a group, but we have no signs that this ever resulted in a lasting hierarchy. We had a division of labour but this never resulted in a large, lasting division of power. There is also a compelling evolutionary reason behind our democratic-egalitarian origins. One written in blood.52

Those who didn’t share, or tried to bully others, were met with harsh sanctions. These ‘counter-dominance’ strategies were originally documented by the anthropologist Christopher Boehm, for a wide variety of foragers. Such strategies to keep would-be dominators in check included teasing, gossiping, shaming, ridicule, and even expulsion from the group. The most severe cases could result in death. Among the modern Ju/’hoansi there was a skilled hunter named /Twa who was causing problems. He was impulsive and brutal, having killed three others. The Ju/’hoansi took matters into their own hands: ‘All the men fired at him with poisoned arrows’ until, one informant recalled, ‘he looked like a porcupine’. Then, after he was dead, all the men and women stabbed him with spears. It was a symbolic way to share responsibility for his death. /Twa’s attempt to dominate his peers cost him his life. The fate of /Twa might explain the few skeletons marked by lethal violence in the Palaeolithic.

This violent edge to egalitarianism began around 2 million years ago. Anatomical changes in our shoulder joint around this time allowed for accurate throwing, whether that be of rocks or spears. (Other primates can, of course, throw objects, but humans can do so with transformative power and precision.)

These physical changes had momentous political implications. Projectiles levelled the playing field, allowing for a single individual or small coalition to easily defeat an aspiring alpha male (as David did Goliath). Even the largest, most imposing fighter could easily be killed

by a spear or poison arrow during an ambush or while they slept. Around the same time, there occurred a significant growth in brain size, with Homo erectus toting a cranium with twice the capacity of a chimp. This growing brain seems to have evolved largely for navigating more complex social environments, helping our ancestors to build coalitions against any single individual who wanted to dominate. Together, these were the evolutionary cornerstones of counter-dominance. They led to the ‘first great levelling in human history’.53