Introduction

‘There are only two ways to live your life. One is as though nothing is a miracle. The other is as though everything is a miracle.’

Albert Einstein

Do you remember a time you had a crappy day and got a hug from someone you love? Or perhaps when you saw that first tree in spring bursting with blossom? A moment when you shared a smile with a stranger without exchanging a word? When a baby fell asleep on you with its full, trusting weight? Or when a sunset peeking through the city horizon stopped you in your tracks? Do you remember how that moment made you feel?

If any of those moments feel familiar to you, or remind you of a similar experience, then you have experienced a glimmer. A glimmer is a tiny moment of joy and connection, which signals to your body that you feel safe. Your muscles soften, your jaw unclenches, your breathing deepens and slows. You feel present and connected. A glimmer can be unexpected – a

beautiful cloud formation seen on the way home from a long day, the happy surprise of your favourite song playing on the radio, someone lovingly taking your hand. Or a glimmer can be anticipated and planned for – the first cup of tea in the morning, spending time in nature, doing a good deed for someone. A glimmer often feels like a little moment of magic, but it’s actually a response that is rooted in your body’s nervous system.

If you haven’t heard of a glimmer before, then we expect you’ve heard of its opposite: a trigger. People are loving the word trigger these days. A trigger is a signal from your body to your nervous system that you don’t feel safe – your heart races, your breath becomes shallow and your muscles tense. Your body’s getting ready for danger: to fight or run away; or to freeze up and get really still so that no one knows you are there; or even to fawn, when you try to appease the threat by being as accommodating and self-effacing as possible. Everyone knows about triggers. Isn’t it funny that we’re all more familiar with the alert part of our nervous system rather than the part that soothes us?

If you’re already thinking, ‘What’s the nervous system?’, don’t worry, we’re going to keep it simple in this book. The easiest way to think of your nervous system is that it has two basic modes: one is ‘survive’ and the other is ‘rest’. Scientists call the ‘survive’ part the ‘sympathetic nervous system’. This is the mode that keeps you on high alert, looking out for threats, anticipating disaster: sound familiar? So many of us live our entire lives this way without even realizing it. The ‘rest’ part is the ‘parasympathetic nervous system’. This is the mode that tells you everything’s okay, when your body settles and rests

and moves into actions that can only happen when you’re calm, such as digesting food. The nervous system is much more complicated than just these two states, of course, but we’re aiming to keep things simple here. Guess which state is more likely to set off triggers, and which is connected to glimmers?

We hope this book will be a gentle guide towards recognizing and appreciating your daily glimmers and learning how to build more of them into your day. Multiple studies have shown that glimmers are something you can train yourself to notice. It’s so common for us to think that happiness in life comes from the big things, such as a beautiful home or a long-term relationship, or career success or financial security. But you can have all these and still have a nervous system that is wired for fear, rather than one that tells you the world is safe and full of connection and opportunity. You can be a multimillionaire, but still feel terrified that you don’t have enough. Or be committed to your dream partner, but full of fear they are going to leave you.

Studies have demonstrated again and again that small daily glimmers – those tiny moments in which we feel present, connected and safe – bring us more sustained happiness than any of these supposedly big and life-changing events. And the good thing is that you can learn to train your nervous system to have greater capacity and resilience, just as you train your muscles in the gym to get stronger. Learning to look out for glimmers and calm your nervous system is like setting your internal GPS to keep you going in the direction of safety, relaxation and spaciousness.

Our nervous systems are developing before we’re even

born and are shaped by our earliest environments and our relationships with our caregivers, as we’ll explain throughout this book. Those of us lucky enough to have loving, stable, consistent upbringings will be more likely to have nervous systems that are wired for connection and stability. Those of us who had more turbulent childhoods – as the two of us did, growing up together as sisters – will develop nervous systems that are more familiar with chaos and instability.

Ever since we were teenagers we’ve tried pretty much everything to ‘fix’ what we thought was broken in us from childhood. You name it, between us we’ve done it, from yoga practice and meditation to raw-food diets, therapy, breathwork, trauma release and magic-mushroom retreats! It’s taken us both a long time to understand that we were never broken in the first place.

We wrote a best-selling book about self-care some years ago, and working on the practices in that brought us to a new understanding of the nervous system. We knew that certain practices worked, such as meditation and breathwork, but we didn’t realize how deeply they affected the nervous system. It’s only in the last five years or so that we have begun to bring this understanding into our work. The pandemic was a crucial moment in helping us understand how we might regulate our emotional responses to ourselves and others. Since then, Nadia has progressed from her yoga teaching deeper into her study of breathwork, while Katia has undertaken somatic-experience training, as well as continuing her work as a TRE ® (Tension and Trauma Releasing Exercises) provider.

This nervous system work has been transformative in how

we live our lives, and it has brought us to a place where we are getting better at managing our triggers and recognizing our glimmers.

Nadia: My default from childhood was to do what others wanted or what I was told to do. I was in a constant state of survival or fawn, always thinking about what the other person wanted or how not to disappoint them, rather than what felt right to me. On a superficial level it meant saying yes to work when I was exhausted, or agreeing to go to a party when I had too much going on. On a deeper level I didn’t express my wants and needs to those close to me. When I go against myself to please others I feel resentful, closed off and defensive. Although I may seem smiling and friendly, there is a heat, a resentment and an anger on the inside. With greater awareness of my nervous system, I am getting better at deciding how and with whom I spend my time. I ask myself: will this deplete or nourish my nervous system? I have noticed that when I tend to my nervous system, I am tending to a deeper part of myself. It is still hard for me to feel like I am letting someone else down by not doing what they need or want, but it is becoming more natural to notice the difference when I choose myself. If I must do things I don’t want to do – and we all do at times – then I make sure I am regulating myself before and after.

Katia : Learning about my nervous system has been really liberating. Our nervous system response changes from

minute to minute, and it’s often rooted in historical patterns, rather than what is actually happening in that moment. For instance, I could be feeling really good and grounded and then walk into the house and totally lose my shit because the kids’ shoes are all over the floor, the coats are not in the right place, just mess everywhere. My heart starts racing, my body gets hot and I am screaming at everyone to put their belongings away. Like it’s life or death. It took me a long time to realize that as a child I lived in a house where I would have to be super-tidy and couldn’t make a lot of noise, so every time I entered my own house my nervous system remembered the past experience and triggered a fight-or-flight response. When I recognized this, I started to practise entering the house telling myself, ‘I am safe, nothing bad will happen to me if the kids have left a mess.’ The more I do this when I enter the house, the more I am retraining my inner guard dog – stroking it, patting it, letting it know it’s okay and can stand down from angry protection mode. This small act is teaching me how I can regulate my nervous system in all aspects of my life.

We aren’t scientists – neither of us even went to university – and this isn’t a science book, but we have included a little bit of explanation of the nervous system to help you understand how glimmers work. We’ve made it as straightforward as we can, because that’s how we understand it ourselves. But if you want to learn about the nervous system in greater depth, we’ve included some recommendations for further reading

from the brilliant psychologist Dr Stephen Porges and the clinician and author Deb Dana (who is credited with coining the term ‘glimmer’ in the first place), as well as Dr Nicole LePera, whose freely shared work online as @the.holistic.psychologist has been so helpful to us both.

We’ve found that when we teach clients and students exercises to regulate their nervous systems, most of them aren’t aware of the nervous system at all. One of Nadia’s clients recently told her, ‘I didn’t even know I had a nervous system until I met you!’ But once they get on board with the concept, they all ask where they can learn more in a way that isn’t intimidatingly scientific and academic. What we kept being asked for is ‘The Nervous System for Beginners’ or ‘Nervous System 101’. We couldn’t find that anywhere, so we have done our best to write the book that would have helped us, our clients and our students if we’d had it years ago.

Glimmers are the tiny moments that open a door to some transformative ways to regulate our nervous system and change our lives and behaviour for the better. And through glimmers we find the easiest and most accessible ways to feel that we can better handle whatever life throws at us.

Throughout the book we’re sharing glimmers that we’ve collected from all sorts of people, living all sorts of different lives. We’ve found it interesting that, although these individuals have diverse experiences of life, their glimmers are often very similar – relating to nature, to moments between people and to sensations of awe or joy. Some of the glimmers shared here will resonate with you, while others won’t. Rather than seeing

them as a set guide to what you should experience, we’d love you to view them as inspiration to notice whatever feels like a glimmer to you.

Working on this book, and the practices included here, has reinforced for us all over again how powerful it is to be aware of our nervous systems and the little moments of joy that sustain our feelings of safety and connection. This awareness and understanding of where some of our behaviour is coming from give us not only a feeling of peace and happiness, but confidence and an inner self- trust. Understanding how glimmers enhance our lives transforms everything from our life decisions to who we choose to be in our relationships and how we engage with the world around us.

A world in which we are able to experience more glimmers than triggers feels like one we’d all like to live in.

Your Nervous System

(the science bit)

The most important step in experiencing more glimmers is noticing them in the first place. Recently Nadia was sitting on the bus, headphones in, eyes glued to her phone. She hadn’t noticed a woman in front sitting with her baby. But Nadia happened to glance up and the baby was looking straight at her, trying to get her attention in that way curious babies do. When their eyes met, the baby beamed the biggest smile for no reason whatsoever. She was so happy to be noticed and seen. This tiny connection lit up not simply that moment, but the rest of Nadia’s day, and this instant of happy connection would most likely have done the same to that little baby, too.

And it was all to do with Nadia’s ventral vagal.

Nadia’s what ?

Okay, this is as science-y as we’re going to get, but stick with us as it’s essential to understanding how all the practices and exercises in the rest of the book work. We fully get the temptation to skip ahead to the practical advice and exercises in the following chapters, but doing this will mean you’re always reliant on the tools offered by someone else, rather

than understanding how to create your own tools to experience more glimmers . We want you to come away with the knowledge, rather than just the tools.

A practice such as yoga or breathwork or singing is calming to the nervous system – we’ll share why later – but we admit that you can experience the benefits without any knowledge as to why they’re happening. What we’ve found is that understanding how it all works allows you to create and refine the tools that work best for you, instead of relying on a yoga teacher or a massage therapist or a particular breathwork practice to restore balance to your body. Relying on others to provide your moments of calm and relaxation is not only unsustainable, but can get pretty expensive!

So let’s take the briefest of scientific journeys towards experiencing more glimmers in your life.

What is the nervous system?

The nervous system is, in the most basic terms, the control system of your body and brain. It regulates your heartbeat, your breathing, your digestion, your temperature, your emotions, your hunger and how you respond to the world around you. It controls movement, hormones, stress response and senses such as sight, touch and hearing. You get the picture: the nervous system dictates how we experience the world.

We’ve read so many descriptions suggesting that the nervous system is how the brain ‘commands’ the body, but

recent science is demonstrating that the truth is more complicated. All the major organs of the body are connected to the brain by a complex network of nerves, collectively known as the vagus nerve. The vagus nerve is like an information superhighway, sending messages from the body to the brain and from the brain to the body.

We were surprised to learn that, far from the nervous system being about the brain giving the body information, 80 per cent of the information that travels through the vagus nerve is going from the body to the brain! This means that your body is constantly giving your brain signals about how to interpret the world and whether you are safe or unsafe. Got a tummy ache? Your vagus nerve carried that signal from your gut to your brain. The vagus plays a key role in how your body senses and responds to internal signals – like digestion, inflammation or tension. But it’s not just about physical sensations. The brain uses this body-to-brain information to help shape your emotions, too, which is why a tummy ache can feel like anxiety, or a deep breath can help you calm down.

Think about when you’re hungry, for example. Your body is giving you a message that it’s time to eat. But you override that message because you are too busy, and then you start getting hangry and snappy and grumpy at people. So your experience of the world, and what your brain is telling you, is that everyone is making you angry, but it’s actually your hunger and dropping blood sugar causing everything to feel this way.

We’re about to give you the most basic explanation of how the nervous system works. It’s possible to go into a lot more

detail on the subject, but that’s outside the scope of this book (although we’ve added recommended reading at the end of the book if you’re interested to learn more). For our purposes we are mostly concerned with how the nervous system tells us either that we are safe or that we are in danger. In other words, are you being glimmered or triggered?

To understand how we might feel safe, we need to understand the three primary states of the nervous system. Deb Dana has a great way of describing these in her book Anchored. She defines the three states in terms of how our nervous system evolved, and we’ve based our explanations below on the hierarchy that she describes.

Dorsal vagal – aka ‘freeze’

This is the most ancient part of our nervous system, the first part to evolve. Think of an animal that finds itself in danger and has no other defence than to freeze. The animal does not exactly feel safe by freezing, but it believes it has no ability to help itself except by shutting down. When we’re in this part of the nervous system we become slower. Our behaviour looks like being closed off, collapsing, disappearing, dissociating, feeling hopeless or depressed. Others may interpret this as being rude or not engaging, which can make someone feel even more isolated. The true freeze state means being immobilized – rooted to the spot in terror, for example. A more common experience is functional freeze, which can feel like going through the motions of life without really feeling anything.

The dorsal vagal/functional freeze response in everyday life:

• Zoning out while staring at your phone

• Avoiding tasks or responsibilities, such as letting unopened emails or bills pile up because facing them feels impossible

• Overeating or skipping meals completely because you feel too checked out to decide what to eat

• Staying in bed for hours after waking up, even though you’re not physically tired, because getting up feels like too much

• Getting lost in thought or staring blankly into space instead of interacting with people or tasks around you.

Sympathetic – aka ‘fight-or-flight’

The next part of the nervous system to evolve in humans was the sympathetic, which is associated with speeding up and taking action. In the sympathetic nervous system state the animal is ready to fight for survival or to run away. The animal is afraid, but chooses action as a defence and responds with either aggression or escape. You may have heard this described as ‘fight-or-flight’. Some of the characteristic behaviours when acting from the sympathetic nervous system are anxiety, defensiveness, irritability, chaotic energy, overwhelm, intense control or a sense that everything feels alarming, catastrophic or threatening. This is very familiar when we’re wound

up about something. It can also be about action or excitement – sympathetic activation is not only negative.

An alternative to fight-or-flight is fawning, when rather than showing aggression we choose desperate people-pleasing as our route to safety – suppressing our own needs and wants for what feels like security. Rather than an animal response, fawning is a learned response, which is shaped by both the sympathetic and dorsal vagal. We have put it in this section because it is commonly referred to as a survival response.

The sympathetic response in everyday life:

• Feeling on edge, constantly ready to react when stressed or overwhelmed. A heightened state of stress

• Feeling irritated or impatient over small things such as waiting in a line or in traffic

• Feeling defensive and overly vulnerable, which can act out as aggression and defensiveness

• Having no boundaries for ourselves and putting everyone else’s needs first.

Ventral vagal – aka ‘in the flow’

The final part of the nervous system to evolve was the ventral vagal – hello, smiling baby on the bus! In this nervous system state the animal feels safety and security. It experiences connection and is able to go with the flow. When acting from the ventral vagal we feel safe, organized, calm, spacious and resourced. We

approach the world with curiosity and interest instead of fear, because we are acting from a belief that we are safe to explore and learn.

The ventral vagal in everyday life:

• Feeling more creative and inspired; when in a flow state – whether writing, painting or moving – you will feel more open, relaxed and imaginative

• Noticing more positive social cues, such as laughing, or smiling with others when you feel connected, safe and socially engaged

• Uplifting energy: you feel excited, eager and able to celebrate achievements

• Experiencing a sense of ease while enjoying moments like a cup of tea, listening to music or going for a walk

• Feeling grateful for all that you have

• Taking care of yourself, nourishing and caring for yourself or carving out time to do things that bring you joy.

It’s tempting to look at these definitions and think, ‘Oh, right, so ventral vagal = good and the others = bad’, but that’s not quite how it works. The truth is that everyone moves between these three different nervous system states all the time, and that’s completely normal and a part of being human. You need your system to be on high alert sometimes, whether that’s meeting a deadline or getting out of the way of a speeding car. And shutting down might be a good idea at times, too, if you’re

in an overwhelming environment or have just received some shocking news. It’s important to remember that your nervous system is always acting to protect you, not to hold you back. It wants to keep you safe.

The only issue is when we get stuck in one of these states for a long time – even ventral vagal can be overwhelming if you’re not used to that feeling of calm and safety! Your nervous system doesn’t always get things right. It tries to keep you safe by sticking to what is familiar, and that may not be in your best interests – for instance, shutting down may help you in the immediate moment of a crisis, but it’s not good for you in the long term. The stuckness is the problem, not the nervous system action.

Remember that it’s normal, and necessary, to fluctuate between nervous system states, and that each of these states is in itself a spectrum (so you might feel a little fight-or-flight or a lot, depending on the circumstances).

In essence we are aiming to build a larger ‘container’ for all our feelings, so that the nervous system has greater flexibility and resilience. Sometimes we’re told that the aim of regulating the nervous system is always to return to a calm state, but that’s not strictly true. Of course we want to feel calm and peaceful, but the true goal is to experience flexibility as we experience all the rich emotional states that come with being human.

The trick is to feel safe in order to experience all of this emotional flexibility, because it is when your body believes you are safe that you are most likely to experience glimmers, which reinforce this feeling of safety and bring you more joy and ease in your daily life.

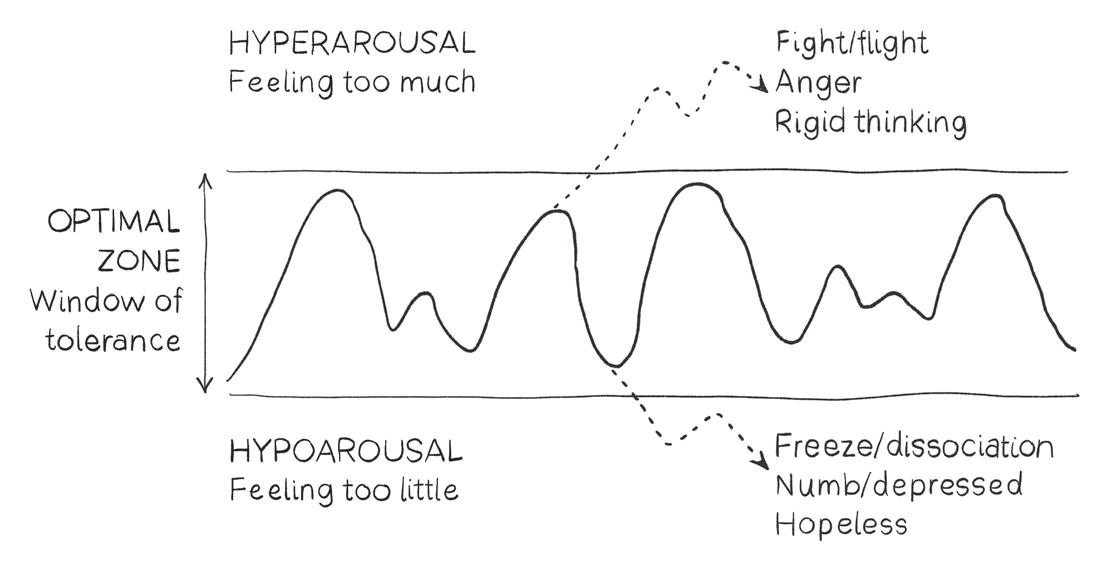

You can see in the diagram below that emotional flexibility means experiencing life’s ups and downs within our window of tolerance. Our goal is to widen that window of tolerance so that we are less likely to move into a state of hyperarousal or hypoarousal.

The body gives us some really clear signals when we are settling into our more regulated ventral-vagal nervous system state. As you slow down and relax you might experience some or all of the following:

• Sighing deeply

• Yawning

• Your shoulders dropping or your jaw unclenching as your muscles relax

• Your stomach rumbling as your rest-and-digest mode is activated

• Slowed breathing

• Slower heart rate (see below)

• Feeling physically present in your body.

You’ve most likely experienced all of these without recognizing that they were signals from your body that you were entering a more relaxed state. Nadia has seen how often people in yoga classes can’t help themselves from yawning – it took a while to understand this wasn’t out of boredom, but out of relaxation!

Trigger a yawn

A yawn might feel like something we have no control over, but in fact we can trigger one. Yawning helps bring the body into a more regulated state by sending the message from the body to the brain that all is well. This exercise looks a little weird, so you may want to do it somewhere you’re not going to be seen!

Open your mouth really wide, like you were about to take a huge bite out of an apple. Keeping your mouth open as wide as you can, take a full breath in and try to make an ‘R’ sound over and over, moving your lower jaw.

We find about six or seven repetitions of the openmouthed ‘R’ sound is usually enough to make yourself yawn at least once, if not more. Try it – we yawned just rereading this paragraph!

Because the brain takes its cues from the body (remember that 80 per cent of the information that passes through the vagus nerve is going from the body to the brain), we can help

ourselves feel more relaxed by consciously bringing ourselves into some of these states – slower breathing, a lower heart rate, relaxing our muscles, initiating a sigh or a yawn – and we’ll share some exercises to get you there.

And, of course, these physical signals can be indicators of when you are experiencing a glimmer: that feeling of security, well-being, connection or even awe.

We understand that the idea of nervous system states can feel a little hard to measure – of course relaxation is a spectrum, exactly as stress is, and there’s no set scale to track these things precisely. But there is one science- backed test that you can try, and here it is.

Resting heart-rate test

There is actually an interesting way that you can test whether your nervous system is in sympathetic (action) or parasympathetic (rest). We learned about this in an excellent book on the vagus nerve by Dr Kevin Tracey,

The Great Nerve. Your Resting Heart Rate (RHR ) is a good guide to whether you are anxious or calm – the lower your RHR , the more likely you are to be in your rest-and-digest relaxation state (lower resting heart rates are also correlated with longevity and a decreased risk of heart attacks, among many other health benefits, which is another reason to aim for a balanced nervous system).

You can test your RHR by first sitting down for a few minutes (you want to be as calm and relaxed as possible) and then locating your pulse with your index and middle finger – usually this is easiest to find inside your wrist. Using a stopwatch, count the beats of your pulse for twenty seconds, then multiply by three to get your RHR .

RHR s vary by age, gender and several other factors (for instance, your RHR will be higher if you’re sick, as your immune system fights off an infection), so we’re not sharing guidance here on what constitutes a ‘good’ RHR , instead we’d recommend that you check yours out at this link: www.medicinenet.com/what_is_a_good_resting_ heart_rate_by_age/article.htm

Most of us have had the experience of going out into the world when we’re in a great mood and seeing how that great mood gets reflected back to us by everyone we meet. And we’ve all had the opposite: a day when everyone we encounter seems mean or rude. And perhaps, if we have a little self-awareness, we might recognize that, on the days when it felt as if literally everyone was mean and rude, maybe we ourselves were going out into the world feeling irritable, defensive and controlling and that will have had an influence on how people responded to us. A good example of this is road rage. There are chilled-out driving days when you are singing along to the radio and letting

people into your lane with a smile while trying to traverse the traffic of the city, and other days when you forget to indicate, cut people up and are convinced that everyone else is a crap driver.

When we see this behaviour through the framing of the nervous system, we can recognize that in the first scenario we are in our ventral vagal: safe, regulated, secure. And in the second we’re in our sympathetic: snappish, chaotic, frustrated. It’s not hard to see how a glimmer is going to be much easier to spot when we are in our calm, safe, secure state rather than feeling as if we’re either shut down or battling for survival.

Katia: Through my TRE ® (Tension and Trauma Releasing Exercises) training I have learned the subtle changes in people’s bodies that communicate which part of the nervous system they are in. Have you ever experienced a friend on the phone telling you a story about a stressful experience? They start talking really fast and loud. This is an indication that they are in fight-or-flight, even though they’re merely describing the experience. At the other extreme, perhaps you have times when you just zone out on your phone or stare into space. This is a sign that you may be dissociating and numbing out. I often go into this space when I feel overwhelmed.

Nadia: As a yoga teacher, I have often talked about a person’s ‘energy’. Since learning more about the nervous system I