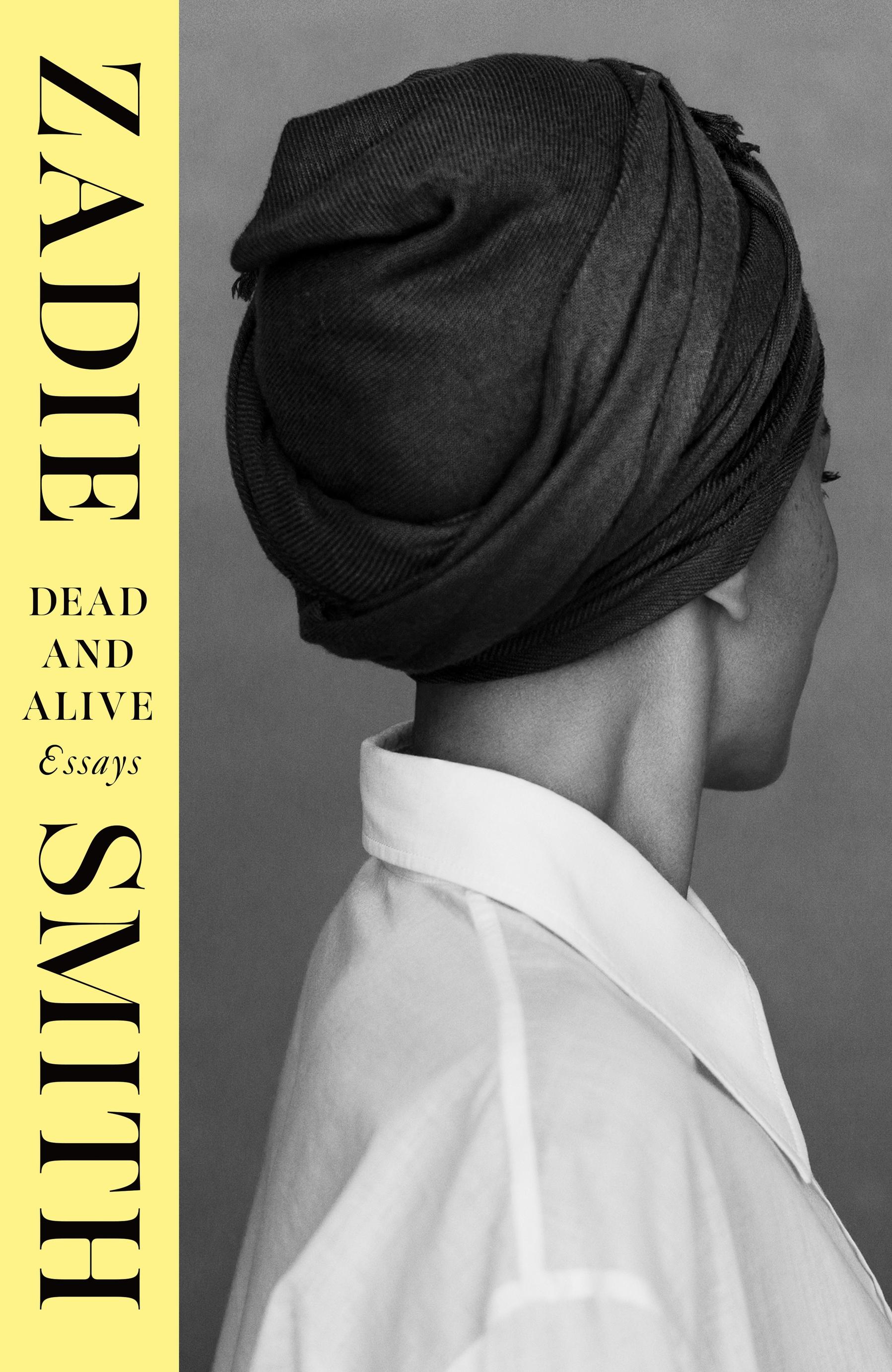

dead and alive

Essays

Zadie Smith

an imprint of

HAMISH HAMILTO N

HAMISH HAMILTON

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Hamish Hamilton is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW

penguin.co.uk

First published 2025 001

Copyright © Zadie Smith, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

The picture credits on page 311 and the permissions on pages 315–18 constitute an extension of this copyright page

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologizes for any errors or omissions and would be grateful to be notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future editions of this book

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception

Set in 12.5/16pt Fournier MT Std Typeset by Jouve (UK ), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

HARDBACK ISBN : 978– 0– 241– 72959– 5

TRADE PAPERBACK ISBN : 978– 0– 241– 72960– 1

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

These essays are dedicated to the memory of Sekeena Gavagan

Foreword: o n Hospitality

You have in your hands a book of essays on many different topics. A tricky proposition. Where to begin? You might start from the first page and just plough through. Or look for a subject that interests you in the Contents, and begin there. You could revisit one you’ve read before, and see how you feel about it now. Or seek out the one you’ve heard about, and see what you yourself make of it. Whichever route you choose, you are welcome. Feel free. Rereading these essays, I notice how many of them begin with me walking into real and/or conceptual spaces and basically encountering something. I arrive as a guest (of the gallery, the book, the movie, the country, the protest, the idea). But as I try to describe what I am looking at or thinking about, I end up being a kind of host, too. Which can also be tricky. In life – as we all know – sometimes it is pleasant to be shown around by your host and sometimes it is annoying or oppressive. As they guide you round, they will inevitably influence the way you experience whatever-it-is, and sometimes you don’t want to be influenced: you want to look at the painting or song or situation through your own lens. But this is where books come into their own. For no one will be surveilling you as you enter this book, nor notice when you leave. On this particular guided tour, I won’t spot you hovering on the edge of the group, annoyed by the guide with her little flag and digressive way of talking and thinking. This book cannot scrub its history as the ground shifts beneath it, nor can it be everything, everywhere, all at once. It

Foreword: On Hospitality

is not being written by an infinite and eternally unscrolling artificial intelligence, but by a human being in a particular moment; one who will never know how eager you were to move on to the next location. Which is all to say: within the covers of this book, you have freedom of movement, and this freedom is absolute.

Another thing people sometimes fear about essays is that they will be too academic, or full of obscure references, which can make a reader feel like she is on the outside of something, or as if she is not welcome. (I experienced that a lot myself as a young reader, especially before the age of the search engine.) With this in mind, I have employed footnotes, introductory notes and postscripts as a necessary evil, but feel free to ignore them if you’re the type of person fortunate enough to already know most of everything. I leave the doors to these essays as wide open as possible, by using language that is, for the most part, as clear as I can make it. The house of an essay may sometimes be strangely shaped or have a complicated floor plan – but the door is open.

Finally, if you are wondering why this foreword is called ‘On Hospitality’, well, that is a nod to one of my favourite philosophers, Jacques Derrida, who wrote a great book with the same title, in which he thinks about how we humans might make space for each other, ideally, in this world.* It is also a very good practical description of the relationship between writers and readers:

Absolute hospitality requires that I open up my home and that I give not only to the foreigner (provided with a family name, with

* Actually, a collection of seminars that Derrida delivered towards the end of his life, in which he considers the question of the ‘foreigner’, and what an ‘unconditional hospitality’ might look like.

x

Foreword: On Hospitality

the social status of being a foreigner, etc.), but to the absolute, unknown, anonymous other, and that I give place to them, that I let them come, that I let them arrive, and take place in the place I offer them, without asking of them either reciprocity (entering into a pact) or even their names.

Reader, I do not know your name – but you are welcome.

Zadie Smith

North-West London

March 2025

European Family

Sometime around 2013, in the middle of a stage interview, a literary critic had an interesting question for me. Why had I begun to write more about the visual arts? And less about books? Answering his own query, he began to muse about the visual turn in the culture, the emergence of the black body as a site of enquiry, the rejection of the white male gaze . . . And kept talking. I nodded and smiled, doing my best to follow, though I hadn’t slept properly in a while and he was using a lot of jargon. Later that evening, much later – whilst propping myself up against a wall with one hand and swinging a Moses basket with the other – I thought: there should be a more

practical arm of literary theory, one that takes into account the realities of women’s lives . . .

I had my first child in 2009. It didn’t take long to figure out that looking at art requires neither both your hands nor silence. That it can be done swiftly, between playground and naptime, and that you can be very tired, looking at art. Sometimes a fugue state even helps! Whereas, if you are trying to breastfeed your baby to sleep, any attempt at simultaneous page-turning will wake them. Even if you transition to a silent Kindle, the contrast between the piecemeal, necessarily time-consuming practice of reading, and the all-encompassing, instantaneous moment of looking, will be stark. All of that is over now, though. No more playgrounds, no more naptimes. And no more teaching. No more marking essays on the soft-top of a buggy. But I still retain the old habit of dashing in and out of galleries like a criminal, especially, for some reason, the Musée du Luxembourg. I love that museum. Small enough to walk around in an hour, even with a screaming child strapped to your torso. I used to teach in Paris, every summer, and each time I dashed in and out of the Luxembourg I would emerge with an idea for an essay. Even if, in the final analysis, I never got round to writing it.

Fast forward, many years. Finding myself in Paris once again, not teaching – and temporarily childless – I hurried from the gardens into the gallery, then reminded myself that the emergency is over: take your time. The show was called Miroir du Monde. It consisted of about a hundred paintings and objets d’art from Dresden’s legendary Cabinet of Curiosities, or Kunstkammer. Collected over two centuries – by the Prince-Elects of what was once Saxony – the Kunstkammer can be thought of as a kind of one-stop-shop, intended to bring together in one place representative examples of the many

and Alive 4

European Family

art treasures to be found upon this earth. A mirror of the world, exactly. At this point you may be thinking (as I did), but surely it all went up in flames, with the rest of Dresden ? In fact, the Kunstkammer was mostly relocated to a fortress on a hill for the duration of the war, and the bulk of it has survived. Now here were some of its marvels right in front of me, magnificent to behold, and yet also somewhat penned in – like one’s true thoughts during a literary interview – by the banal framing of somebody else’s words. In this case, a curatorial description:

This exhibition places an emphasis on the artistic quality and provenance of the works which not only reflect the many global relationships and cultural exchanges, but also the Eurocentric world view they embody. A few historical objects are arranged so as to mirror works by contemporary artists, putting these historic collections into perspective through the key issues of our time.

The key issues of our time turned out to be basically the one issue, that pesky white male gaze once again, a critique impossible to argue with – as far as it went. Take, for example, Moor with Emerald Cluster by Balthasar Permoser, circa 1724. About fifteen inches high, he is a muscled youth, a noble savage type, and therefore, yes, for sure a familiar Eurocentric cliché. Carved from pear wood, lacquered a very dark brown, he is depicted half-naked, multiply tattooed, wearing gold cuffs, gold necklace, a feathered and bejewelled headdress, and holding a platter of emeralds – all while grinning like a figure from the commedia dell’arte. The museum had helpfully put him under a spotlight in his own corner, presumably so that we might all focus our Eurocentric gazes upon him, and dutifully note what a perfect example of exoticization he was, and

and Alive

fetishization of same. Still, he was beautiful.* Far more egregious were two laughing ‘Chinese’ porcelain busts, 1732, produced by the Meissen factory. These gargoyles managed to combine the physical clichés of Asian physiognomy – as caricatured by European artists† – with a wild, near total ignorance of traditional Chinese dress, as if the artist did not even know enough of the truth to satirize it. The woman – who seemed to be kitted out like a Dutch milkmaid – wore a fantastical hat that turned up at each end and featured a lot of incongruous bobbles and tassels, while the man’s hat looked no more Chinese than the baseball cap upon my own head. Fictional creations, these two, from a nowhere place called ‘Foreign’. Looking at them I realized I felt a little sorry for the much vaunted, much dreaded, ‘Eurocentric world view’. Supposedly allpowerful, and yet so incredibly ignorant! It does not know what it does not know. It conjures up a beautiful Moor – carrying emeralds stolen from the New World, to be presented to the Old‡ – but then dresses him incongruously, borrowing his costume from a series of contemporary images of sixteenth-century America.§ That’s how he ends up tattooed like the Native Americans of Florida, and in their ceremonial costume, too. His feathered headdress meanwhile

* None of his features being especially exaggerated or satiric, I guiltily bought him in the giftshop, in postcard form, to admire later, alone and in private. He’s on my desk as I write this.

† In this case very long and undulating ears. A racist trope perhaps common among eighteenth-century Germans, but obscure to me.

‡ Moor with Emerald Cluster was a gift for King Rudolf II .

§ The New World by Theodore de Bry, 1590. Within which there are engravings illustrating episodes from the failed French settlement in Florida. The tattoos on the Moor are copied from those on the body of Saturioua, a formidable Native American Floridian king.

European

Family

is drawn from an even stranger source: Montezuma II , the ninth Aztec emperor of Mexico. Eurocentric. The word itself began to feel a little too self-regarding. Euro-blindness? And besides, shouldn’t there be another, more specific word to describe the act of plunder and purchase, into which category at least a third of the objects in the Kunstkammer truly belong? Such objects embody no ‘Eurocentric world view’ – how could they? They are not the product of Europe at all. And how dazzling!

An engraved ivory horn from Senegal.

A painted Japanese teapot.

An Iranian scimitar, encrusted with precious jewels.

All exotic from the perspective of Saxony, but never exotic in and of themselves. Rather, they sit at the very centre of their own worlds, conceived and constructed by master craftsmen, whose skills and materials were – like Chinese porcelain – sometimes copied and poached by Europeans, but whose roots lay elsewhere. And yet, of course, once contact is made, and those ‘cultural exchanges’ noted by the curators occur – between Old World and New, ‘indigenous’ and ‘civilized’ – at that very moment, an impure and ungovernable channel of influence inevitably opens up, through which ideas will pass back and forth, until the category of ‘exotic’ begins to look like a moveable feast. For who, exactly, is exotic to whom?

In the Luxembourg Museum there was only one possible answer to that question. It was as if the curators, in their wisdom, had decided to take power – especially colonial power – at its own word. That is, as all-conquering. As eternally and uniquely capable of labelling and locating the exotic ‘other’ in the colonized, the subjected, the indigenous. As not only militarily and economically triumphant but also aesthetically and psychologically. In fact, by some perverse circularity of logic, the ‘Eurocentric world view’ was basically being

Dead and Alive

re-presented to me in more or less the same terms in which it had once fondly thought of itself, nearly three hundred years ago. This self-belief in Europe’s own prepotency is, of course, a part of the Kunstkammer ’s history – a large part. But it is not and can never be the whole story. Power dominates, but art proliferates – and not always along the lines that power dictates. For art, unlike power, can never be wholly unidirectional, artists themselves being at once too voracious and impure in their methods. Whether members of dominant or subjected communities, they will prove capable of appropriation, hybridization, adaptation. To put it another way: while the master isn’t looking, many interesting things will be made with his tools. As for his notorious gaze – however powerful it might be – it can never completely stop him from being seen, by others, for what he really is. Even colonial subjects have eyes.

I left my spotlit Moor where he was – patiently holding his tray of gems, awaiting the fresh pity and ready-made critique of another busload of European tourists – and walked on. Onwards, into the second room, where I spotted an object that stopped me in my tracks. It was far less spectacular than the Chinese heads or the Moor, and sat half-ignored under Perspex, poorly illuminated, easily missed. Just a little piece of Chinese porcelain called European Family – but it made me laugh out loud. I couldn’t help but think of the Chinese artist who had made it. Was it a commission or simple curiosity that had led him to his subject? Had he* ever seen a European family? Perhaps he had seen the many portraits of them and wondered at

* It would be interesting to discover how many artworks in the Kunstkammer were crafted by a woman’s hands. I’m going to guess zero? That’s one thing the Old World and the New World had in common: women’s hands were filled with babies.

them, there being much to wonder at. Why, for example, did they tend to depict themselves in such a pitiful, meagre, nuclear fashion: father, mother, kids? Where were their ancestors? Where were their dead ? And why so many mangy dogs? Were dogs more important to European families than ancestors ? Sometimes they even brought in a monkey and depicted him as a funny little thing – as a pet! As if a monkey were not a god! Also: what is with the headwear? Very large and yet also sort of non-functional? Like literally what is the point of it? Does it keep off the sun or the rain? Feels like it would instead direct rain through a funnel back into your face? And is it the Spanish ladies that wear the dome-like veil things? Or is that the English? The Catholics or the other ones? Does it matter? Are there, like, even any important differences between the Spanish and the English? Not really?

He may not be quite clear on all the local details, but I really like the things our Chinese artist has correctly surmised about the ‘Other’, and sees fit to include in his idiosyncratic vision. The weirdly vulgar way, for example, that European man likes to man-spread, lifting one leg at a right angle to the other, exposing his genital area, and thereby using twice the lateral space that sitting with his legs neatly together would have taken up. Also, the fact that, within a European family, people can often seem quite distant the one from the other, to the point that sometimes, in their portraits, it looks as though they have never really even met. Their food looks – how to put this? – unappetizing. And maybe not that flavoursome? A boiled chicken leg. Some cabbage. And why are their dogs allowed so close to the food ? That doesn’t seem right. And oh boy do these Europeans love buttons. Chinese buttons are also a thing of course but the artist might be forgiven for feeling that the buttons of his own people are more functional and discreet. Here we have just

and Alive

so many buttons on everything. Big shiny metal buttons that seem more for show than for use, and also there’s the silky neckerchiefs and cravats, and stockings and garters, and just a surprising amount of florid and apparently unnecessary decoration on these European men who, in other realms of life, seem to take themselves so very seriously. Finally, European families drink. A lot. Drink seems to be central to the whole escapade of being a European family. Unclear why. Maybe it’s the only way to survive one? Look how they grasp their goblets with a strange tenacity, as if it is very important to them to keep the beer and/or wine or whatever it is they drink flowing and on hand at all times, perhaps because it muddles the mind, calms dark thoughts, eases guilt, renders one forgetful and selfaggrandizing, and lets you go to sleep as soon as your head hits the feathered pillow, like a man with a clear conscience.

The Muse at Her Easel: Celia Paul’s Self-Portrait

This essay concerns a book called Self-Portrait by the British painter Celia Paul, which is an autobiographical account of her development as an artist. You can find reproductions of a few of her paintings in the picture inset.

The word museography properly refers to the systematic description of objects in museums, but it might also do for the culture and ideology surrounding that dusty old figure of legend, the artist’s ‘muse’. If her aura is fading now, anyone educated during the twentieth century remembers when she played no small part in our curricula, both formal and informal. (The male muse, back then, existed only in the homosexual realm.) To avoid her, you had to spend a lot of time in libraries seeking evidence of her opposite: not the sitter but the painter; not the character but the author; not the song but the singer. And a few women did appear to have avoided the state of muse-dom: Virginia Woolf, Gertrude Stein, Zora Neale Hurston, Patti Smith. In fact, such women could be said to have acquired muses themselves, or to have been involved in a mutually beneficial muse-ology with other artists (Vita Sackville-West, Alice B. Toklas, Langston Hughes, Robert Mapplethorpe). But it was slim pickings.

Meanwhile, in the annals of museography, you could discover a

Dead and Alive

celebrated parade of handmaids to the genii, ‘legendary beauties’, ladies with salons, chic ladies, witty ladies, ladies with inspiring ankles, faces, breasts, voices, clothes, attitudes, houses and inheritances; women whose brilliant conversation had been entombed in various novels; women whose personal style had prompted whole fashion houses into production; women whose tenure as girlfriend or wife usefully demarcated the various artistic ‘periods’ of the male artists with whom they’d been involved, even when those women were also, themselves, artists. The Yoko Years. The Decade of Dora. Accounts of the muse–artist relation were anchored in the idea of male cultural production as a special category, one with particular needs – usually sexual – that the muse had been there to fulfil, perhaps even to the point of exploitation, but without whom we would have missed the opportunity to enjoy this or that beloved cultural artefact. The art wants what the art wants. Revisionary biographies of overlooked women – which began to appear with some regularity in the eighties – were off-putting in a different way (at least to me). Unhinged in tone, by turns furious, defensive, melancholy and tragic, their very intensity kept the muse in her place, orbiting the great man.

Celia Paul’s memoir, Self-Portrait, is a different animal altogether. Lucian Freud, whose muse and lover she was, is rendered here – and acutely – but as Paul puts it, with typical simplicity and clarity, ‘Lucian . . . is made part of my story rather than, as is usually the case, me being portrayed as part of his.’ Her story is striking. It is not, as has been assumed, the tale of a muse who later became a painter, but an account of a painter who, for ten years of her early life, found herself mistaken for a muse, by a man who did that a lot. Her book is about many things besides Freud: her mother, her childhood, her sisters, her paintings. But she neither rejects her past with Freud nor rewrites it, placing present ideas and feelings alongside diary entries and letters

The Muse at Her Easel: Celia Paul’s Self-Portrait

she wrote as a young woman, a generous, vulnerable strategy that avoids the usual triumphalism of memoir. For Paul, the self is continuous (‘I have always been, and I remain at nearly sixty, the same person I was as a teenager . . . This simple realization seems to me to be complex and profoundly liberating’), and equal weight is given to ‘the vividness of the past and the measured detachment of the present’. You sense both qualities in her first glimpse of Freud, in 1978:

His face was very white, with the texture of wax. It had an eerie glow as if it was lit from within, like a candle inside a turnip. His gestures were camp. He stood with one leg bent and his toes, in their expensive shoes, were pointed outwards. He sucked in his cheeks in a selfconscious way and opened his eyes wide until I looked at him, and then his pupils, which were hard points in his pale lizard-green irises, slid under his eyelids and I could only see the whites of his eyes.

In the head of the muse were the eyes of a painter. At the time, she was at her easel, watching Freud enter the basement life-drawing class at the Slade School of Fine Art, where he was a visiting tutor. He liked to make a dramatic entrance. In Paul’s case, it all happened with unseemly speed. In a moment he is beside her; she shows him some drawings she has done of her mother; a painting of her father. He touches her back, suggests they go for tea, and after that tea, they get in his car:

As we drove west the low autumn sun was blinding. He took my hair and wound it around his fingers and started stroking my throat with a soft rotating movement. I felt his knuckles on my throat through my hair. He stared at me fixedly and told me I looked so sad. He asked me for my phone number.

At his flat, more tea:

As I was drinking it, he came and stood behind me. He lifted up my hair and buried his face in it . . . He pulled me gently but insistently into a standing position. I watched him kissing me and my mouth was unresponsive. I saw the whites of his eyes and he looked blind. His head felt very small and light as eggshell. I was frightened. I asked him what he thought of my work. He said that it was ‘like walking into a honey-pot’.

Talk about Freudian! Though I wonder if they’re thinking of the same honey-pot? For a muse, the sweet temptation is validation: you want to know what the great man thinks of your work, even if the great man wants something else first:

He started to kiss me again, but I was insistent that I had to go back now. I told him that I had arranged to meet up with a life model, who I hoped would be able to sit for me privately.

In museography, art and sex struggle with each other, intertwine, become finally indivisible. But when the muse happens also to be an artist, the struggle is existential, because to submit entirely to musedom, to being seen rather than seeing, would be to lose art itself:

As I was leaving I noticed a beautiful unfinished painting by him . . . It was of a woman with her head resting on one side in a dreamy reverie. Her mouth was half-open. The image was full of love. When I was halfway down the stairs I heard him calling after me in a gentle voice, ‘Thanks awfully.’

The Muse at Her Easel: Celia Paul’s Self-Portrait

Paul, young or old, does not scorn the idea that gratitude can exist between muse and artist, and move in two directions: love lessons becoming art lessons, and vice versa. But she does not romanticize the price of entry, and from the start knew to be cautious. Rather than meet Freud the following week, she avoids the Slade, preferring to stay at home, drawing. He starts calling. She agrees to meet him in Regent’s Park, where he spontaneously begins kissing her waist (‘I felt very sad, also unnerved’). She meets him the following day, at his insistence. The moment she arrives at his door he presses her against the wall and starts kissing her again. In an attempt at ‘winsome prevarication’, she tries reciting Yeats’s ‘He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven’, but he ‘seemed rather irritated’ by it and soon leads her to bed. ‘I felt that I had sinned and that something had been irreparably lost. I felt guilty and powerful. I felt that I’d stepped into a limitless and dangerous world.’ She was eighteen. Freud was fifty-five. Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.

So ends the section called ‘Lucian’ that opens the book. It is directly followed by ‘Linda’, a chapter concerning the artist as a young girl, and within which Paul makes clear that it was her own childhood – rather than her encounter with Freud – that made her a painter. Inspired primarily by the Devon landscape in which she was raised – ‘I found objects on my walks through the woods and on the beach . . . and I arranged them to form still-lifes. I painted obsessively’ – a little later she had a creatively significant ‘intense relationship’ with a girl at her boarding school. Her name was Linda Brandon.*

* The non-chronological location of this ‘Linda’ chapter – which would place a man’s effect on a woman above her own formative experiences – is interesting, and perhaps related to the effects of musedom on the editorial departments of publishing houses.

Dead and Alive

Their relationship was non- sexual, urgently creative, extremely competitive, and centred around the art room of their school, to which both girls had been given a key by their art teacher. Each worked secretly, separately, late at night, inspired by envy of the work left behind by the other. Paul was ‘astonished’ by Linda’s drawings, experiencing surges of jealousy so sickening ‘I thought I was going to pass out’. They match each other picture for picture, until, after one summer holiday, Paul comes back with a ‘huge amount of work’, while Linda has completed only one ‘half- finished drawing done in heavy black pencil of a dried sunflower head . . . I sensed, with relief, that her passion for painting was beginning to fade.’ Linda, vanquished – although still loved – takes up a place at a normal sixth- form college. Paul is put forward for the Slade. Lawrence Gowing, a professor there (and friend of Freud’s), took one look at her portfolio and immediately approved her application, even going so far as to write an encouraging letter to her ‘reluctant’ father. (Including the memorable line ‘Pictures unpainted make the heart sick.’) If this chapter reads like a foundational myth of female ‘becoming’, ripped from the pages of Charlotte Brontë or Elena Ferrante, it’s no surprise. Girlhood seems to be one of the few periods of a woman’s life where her creativity can exist wholly without shame: unbound, feverish, selfish. In adulthood, things change. Female creativity finds itself in conflict with traditional feminine responsibilities:

One of the main challenges I have faced as a woman artist is the conflict I feel about caring for someone, loving someone, yet remaining dedicated to my art in an undivided way . . . It was a conflict of

The Muse at Her Easel: Celia Paul’s Self-Portrait

desire that I suffered at first with Lucian . . . He spoke admiringly to me of Gwen John, who had stopped painting when she was most passionately involved with Rodin, so that she could give herself fully to the experience. I felt that there was a hidden reproach to me in his words.

Not so hidden.

There is a tension between seeing and being seen. When the young Celia Paul first sits for Freud, she is ‘very self-conscious, and the positions I assumed for him were awkward and uncharacteristic of the way I usually lay down. I was never naked normally.’ She ends up covering her face with one hand and cupping one breast with the other. (‘ “That’s it!” he said. I knew that it was the way the skin of my breast rumpled under the touch of my hand that had attracted him.’) It’s when he paints her breasts that she’s most aware of taking on the role of object: ‘I felt his scrutiny intensify. I felt exposed and hated the feeling. I cried throughout these sessions.’ The painting is Naked Girl with Egg, because Paul’s breasts reminded Freud of eggs. He also painted an actual egg cut into two halves in the foreground of the picture – in case, perhaps, the connection was obscure. One effect of the egg is to emphasize how much the flesh looks like meat beside it, and the material under Paul like a tablecloth, as if she herself is part of the meal. By contrast, when it’s Paul’s turn to do the seeing, consciousness of objectification and its consequences became part of her process. Her first satisfying life-drawing experience is with an Italian model called Lucia, with whom she feels a special connection, because, ‘unlike the other life models who never showed their feelings’, Lucia weeps, and describes feeling degraded by the filthy mattress at the

Dead and Alive

Slade, by the students who never speak to her. Paul began to develop a different understanding of what it means to see and be seen:

I couldn’t understand the principle of life drawing. It seemed so artificial to me to draw a person one didn’t know or have any involvement with . . . I needed to work from someone who mattered to me. The person who mattered most to me was my mother.

Throughout her career, Paul has painted only people and places she knows well: her son, her four sisters, her father, and especially her mother, over and over again, using her own emotional relation to them as an aesthetic principle: the portraits ‘were necessary because I loved [my mother]. Their necessity gave them their force.’ In her view, ‘the act of sitting is not a passive one’, and can be noticeably different for women and men:

I have noticed that the men I have worked from are interested in the process of painting and in the act of sitting. The silence, when I am working from men, is less interior. Women, in my experience, find it easier to sit still and think their own thoughts, and they often hardly seem to be aware that I’m there in the same room. For this reason I usually feel more peaceful when I’m working from a woman, and more free.

In the case of her mother, who was religious (Paul’s father was a bishop), this stillness had the added dimension of faith, for she was often silently praying during the many hours she sat for her daughter:

She entered into the silence with her soul. Her face assumed a rapt expression. My painting was raised to a higher level, too, because of

The Muse at Her Easel: Celia Paul’s Self-Portrait

her elevated state. The air was charged with prayer. She was always ecstatic if she felt she had sat well.

With his own sitters, Freud liked to talk and be listened to. Paul records some of this conversation in a letter she wrote home:

He said much more, like how the Greek sun seems to preserve the colour in cloth and furniture so that a regency chair is startling but that women start to go downhill at an avalanche pace from the age of sixteen etc. etc.

Freud painted the visible: flesh, breasts, eggs. Paul’s work is a visionary account of ineffable qualities, like love, faith, silence, empathy. All of which can be made out in what she calls her ‘first real painting’, Family Group. Gowing called it the best painting done by a Slade student. Freud admired it, too, as Paul does not omit to mention:

He said, ‘I’m thinking of your painting.’ He started to think about doing a big painting involving several sitters, and he ordered his biggest canvas yet to be stretched . . . On this canvas he was to conjure up ‘Interior W11: After Watteau’.

One of the subtle methods of this crafty book is insinuation, creating new feminist genealogies and hierarchies by implication. Is Interior W11, for which Paul posed, after Watteau – or after Paul? There are the similarities in the composition: the resting hand, the averted eyes, the cramped space, and the rectangular escape-hatch – for Paul a mirror, for Freud a door, but in both cases opening onto a different view, like a release valve from the intensity of family life.

Dead

and Alive

But to imply a mutual influence between these painters is also to highlight the differences in approach. In Paul’s painting, wavelike brushstrokes surround the family and seem to connect them, like auras, radiating most intensely around their heads, as if the mental conception of familial love were a sacred substance itself, that paint might render visible. (Paul is present in the mirror’s reflection, thin and spectral, a benign spirit watching over her clan.) ‘The whole composition,’ Paul writes, ‘is lit with an inward glow.’

In Freud’s painting, Paul – the new lover, at far left – must contend with her lover’s children and stepchildren, as well as the ex-lover, Suzy Boyt, who had four children with Freud after also meeting him at the Slade, twenty-five years before Paul. This improvised family group sits together in a room of little warmth – rusting pipes, peeling paintwork, half-rotten greenery – against which they are each sharply outlined, like anatomical examples of their kind. Under their skin, Freud uncovers his familiar butcher-shop pinks, his blues and greys – suggestive of veins, arteries and organs – which are then echoed in the meaty shades of the exposed walls, and likewise make the case for inevitable decay.

‘The forms grew bigger as he progressed,’ writes Paul of the construction of Freud’s painting:

So that we appear to be squashing up next to each other. Despite the physical proximity, each figure seems locked into her or his private world and there is no emotional empathy between us. We look lost and isolated, like sheep huddled together in a storm.

The storm, of course, was Freud himself, father of fourteen acknowledged children with six women. Traditionally, museography has considered critiques of such arrangements tediously puritan.

The Muse at Her Easel: Celia Paul’s Self-Portrait

(Although, by the time Freud died, in 2011, a grudging shift was taking place. You can hear it in some of the posthumous profiles: ‘As raffishly bohemian as these arrangements may sound, it was no easy road for the women and children involved.’) Interior W11 aestheticizes the complex family romance Freud liked to cultivate around himself. (He seemed to require, Paul delicately suggests, an ‘undercurrent of jealousy . . . as a stimulus to his own affairs’.) It’s less a group portrait than a staged drama about power, depicting five atomized people tethered to a central figure not pictured. They are all there for Lucian, only for him. Of course, this is true of all portraits – the sitters always appear at the artist’s bidding – but few painters have put as much emphasis on sitting-as-subjection. (The youngest child looks less like a child reclining than a rag doll, destined to remain wherever you drop her.)

A year into their relationship, Paul discovered that Freud had several young lovers at the Slade. Devastated, she cautiously expressed her pain to Gowing, he of the kind letter about unpainted paintings. But by now, Celia was a muse, so a different kind of advice was in order:

He says that he has known Lucian since he was sixteen and knows that he just doesn’t commit himself to one single person – not through unconcern but just because this was the stony cold mode of living that his art flourished on.

Paul records her subsequent suicide attempt with surreal British restraint, in five sentences, never to be mentioned again:

Everyone at the Slade was gossiping about Lucian, and they delighted in telling me about all the people he was having affairs

Dead and Alive

with. I became severely depressed. One night I swallowed a packet of Veganin [a painkiller], washed down by a bottle of whisky. This landed me in hospital. I went home to recover.

After this she remains with him. Anyone who has ever waited for a text or an email from a lover – but never known the pain of the landline or the postal service – will marvel at the old ways, when a woman could find herself constrained to the house for days, awaiting a sign. And he remains promiscuous. Sometimes he gaslights her about it (‘You’re crazy’). Sometimes he defends it (‘It doesn’t alter what I feel for you’). Sometimes he claims the bohemian’s licence (‘I don’t know if it’s right and I don’t know if it’s wrong’). Sometimes he forgets what he said before and has to adapt:

‘You lied to me.’

‘When did I actually lie to you?’ He is very gentle to me.

‘When I asked you if you were going with anyone else you said – of course not.’

‘Oh yes,’ he murmurs. ‘You know I almost always tell you the truth.’

Sometimes her teenage diary displays the same cool insight that distinguishes Self-Portrait as a whole: ‘He does not love me.’ More often, she proved a child at sea, caught in the eye of Storm Freud:

His mood is brittle gentleness. I say one careless foolish word and he flings a hundred back at me, so angrily, so full of hatred, and then the ice-cold kindness seals the crack again and I am left feeling completely humiliated. Soon I lose my voice, my thoughts are covered in mist.