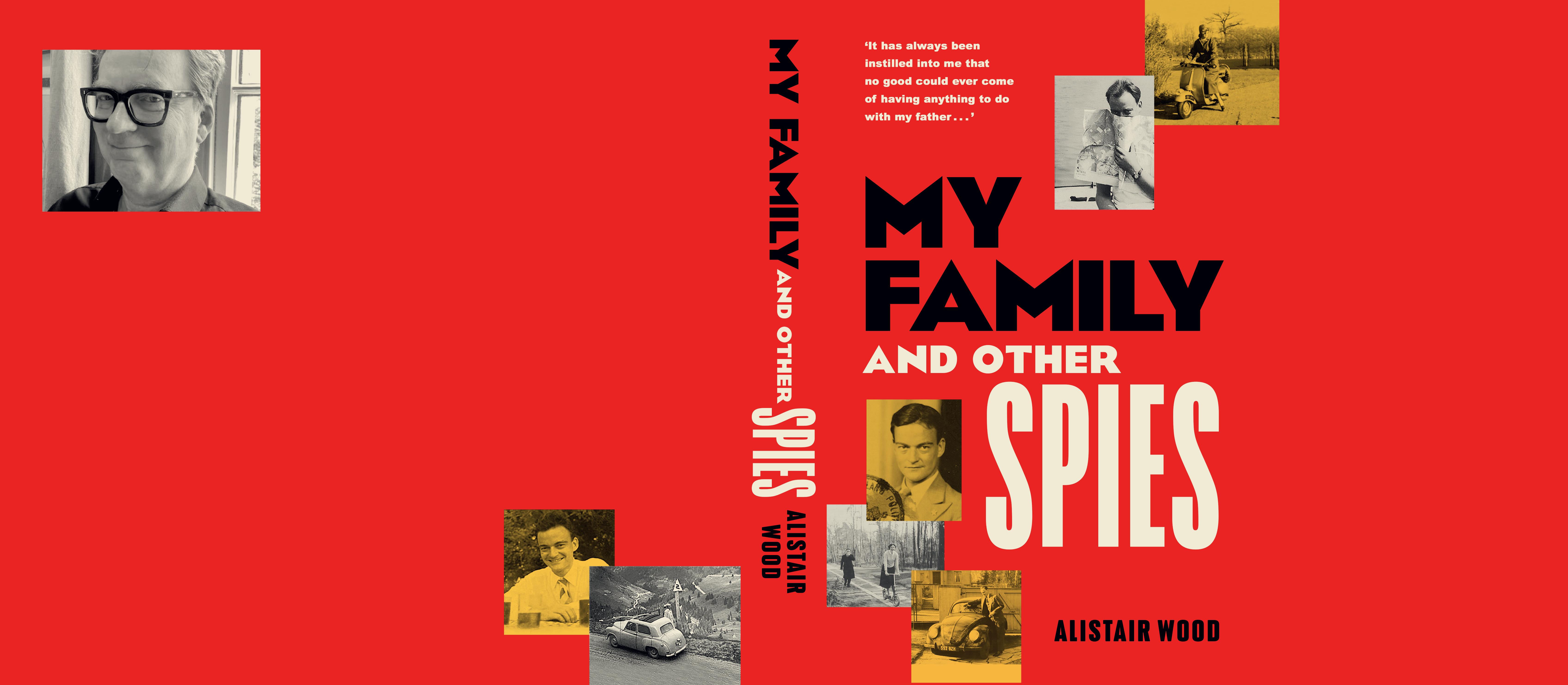

My Family and Other Spies

PENGUIN MICHAEL JOSEPH

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Michael Joseph is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London sw 11 7bw penguin.co.uk

First published 2025 001

Copyright © Alistair Wood, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception Set in 13.5/16pt Garamond MT Std Typeset by Jouve (UK ), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the eea is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d 02 yh 68

A cip catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library hardback isbn: 978–0–241–72635–8 trade paperback isbn: 978–0–241–72637–2

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

Blether. A Scottish word, meaning foolish talk, nonsense, exaggeration.

But in our family it meant quite the opposite.

It covered anything that was true but to outsiders would sound like foolish talk, nonsense or exaggeration.

This included any mention of where my mother worked, what she did for a living, even where we lived. And, heaven forbid, any mention whatsoever of my father.

Rest assured, what follows is pure, unadulterated blether.

Introduction

‘I don’t suppose we’ll ever really know the truth about J. B. Wood, will we?’

Harold Shergold, SIS Soviet Bloc controller 1954–71, to author

As far back as I can remember, once or twice a year my mother would drive us up to London to spend the day with ‘Shergy’ and his wife, Bevis, at their Richmond Park home. I have photographs of my brother and I feeding the deer, boating on the Pen Ponds, up to our knees among the reed beds. But of course I have no photographs of Shergold himself, long since weeded out, more likely never taken in the first place.

Close friends of my mother ever since she stepped off the train into the deep end of the so-called ‘Agentensumpf ’ or ‘agent-swamp’ that was Berlin in 1949, they remained so throughout her life – Shergy gave the eulogy at her funeral. In the years since, he kept in occasional touch, and every now and then I’d be press-ganged into dog-walking duties round Richmond Park, he and Bevis having spent their retirement years training guide dogs for the blind. So I was met with much excited tail-wagging by his latest recruits, Westley and Larry, when I arrived at his home, the ground-floor apartment of a flat-roofed, modernist house backing directly onto the park itself.

Shergy was by now well into his late eighties, and his health had begun to fail. His breathing was not good and he had a rota of (mostly Kiwi) carers ‘who keep an eye on me’, one of whom had prepared lunch for us, laid out ready on the dining-room sideboard. First things first, he insisted we head across the road to the Star & Garter Home, a residential care home for ex-servicemen and -women where Bevis had spent the last months of her life. He was keen to show me a glass-topped display case of her athletics medals (she competed in the shot put at the 1948 Olympics) installed on the first-floor landing in her memory. Our slow progress up the main staircase was not helped by a constant stream of people stopping to wish him well: anyone and everyone knew Shergy, it seemed. Later though, as he got his breath back and we peered down at Bevis’s various certificates and medals, he twinkled, ‘Of course, no one here knows who I am.’

During lunch he kept the conversation to everyday matters: his health, dogs past and present, family, what I was up to, after which he shuffled me through to the sitting room, motioning to two fraying armchairs. The room was much as I remembered: the heavy desk with the familiar black upright typewriter in one corner, the same two paintings of Venice and, behind me, the low bookcase with its well-worn school textbooks. My mother had once teasingly asked what job I thought Shergy did, and I can remember guessing that he might be a (rather genial) schoolmaster. As he had been once, only for the Second World War to map out an altogether different path for him.

Just two books referenced his second career. Battleground Berlin, jointly written by an ex-KGB officer and two of Shergold’s former CIA colleagues, told the story of Cold War

Berlin from both sides, but it contained little if anything that my mother and her Berlin friends used to ‘natter’ about. On the other hand, Tom Bower’s The Perfect English Spy did, and even included a distant, slightly blurred photograph of Shergold walking one of his dogs down to the ponds, a rare time he’d been caught on camera.

Normally anything to do with ‘the office’ – as Shergy and everyone in our family referred to the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS ) – would be held back until I had my coat on ready to leave, and even then it would be for perhaps a minute or two at most. Nor do I recall there ever being much mention of my father, a subject best avoided. But then not having been brought up by J. B. Wood, I had no great personal interest in the subject, as I was quick to point out. ‘No, of course not. Why would you? No. Why ever would you?’ Shergy agreed.

Perhaps this visit would have been no different had not fate intervened. One moment he was sat upright in his armchair, the next he was doubled over, struggling for breath. No expert, I hesitated (correctly, it turned out) to slap a frail eighty-something man on the back. It was touch and go – desperate stuff – before he finally managed to crane his neck into a position where he could gulp some air. A few moments to collect himself, then a wry smile: ‘Wouldn’t have looked good, would it?’ No need to decode: finding the son of an ex-employee of frankly ‘questionable loyalties’ standing over the still-warm body of the former head of SIS ’s Soviet Bloc operations might have raised a few eyebrows in certain quarters.

On the unspoken understanding that this might well be our last such meeting, with a series of nods, frowns, prompts, anecdotes and the occasional name, Shergy proceeded to run

xi

me through the facts about J. B. Wood as he knew them and steered me towards the truth as he understood it: their time together in Berlin, operations they’d worked on, the frustrations of working with him and, not least, the reasons for his summary dismissal from SIS . Only now I was hearing the true version of what exactly had led to this, rather than the ‘official’ version.

Driving home that evening I was aware that my visit had been less a spilling of beans, more a briefing. ‘I very much enjoyed your visit and the opportunity it gave me to reminisce and think of past events and former colleagues,’ Shergy wrote afterwards. ‘The older one gets, the more one tends to live in the past. I suppose that this particularly applies to those of us who live alone.’

For Shergy, it seemed, J. B. Wood remained unfinished business, and I was being asked to fill in the gaps – though quite how he expected me to succeed where the finer minds of SIS had come up short he gave no clue, other than to suggest that ‘these days I suppose you could always try the Russians’. More to the point, it had long been inculcated into me, not least by Shergy himself, that no good could ever come of having anything to do with my father.

Given the unlikely prospect of any relevant SIS files ever being released – if any still exist – in attempting to piece together something of my father’s story, I’ve had to resort to an additional, unexpected source: my own upbringing, the majority of which was spent ‘above the shop’, within the four (very high) walls of the SIS training camp. But for this most unusual, not to say impossibly unique head start, very little of what follows could have come to light. Nor, of course, would I have had ‘by a long

way the most important and influential officer of the postwar period’ to set me on my way.

A few months after our get-together Shergy sent a short note to say that Larry had died, leaving just Westley, the last of his dogs, and that ‘since I last saw you, I have had a further relapse health-wise and my breathing is very much worse than it was when you were here’. And then one evening, driving out of Richmond Park, I glanced back only to see a ‘For Sale’ sign across the road from the old Star & Garter Home.

There had been no notice in any newspaper, not a single obituary, not even – at his insistence, legend has it – a funeral.

part one

Staick House, Eardisland. Despite online posts lamenting its abandoned state, JBW’s cousin was still living there, August 2000.

Brother, mother and author reunited following brother’s kidnapping, April 1959.

1. Southampton Docks car park

‘We’re just going out for a loaf of bread. We might be a while.’

J. B. Wood, 23 July 1958

Given that one of the few things I – or anyone else for that matter – could say for certain about my father was his place of birth, this seemed as good a place as any to start.

The village of Eardisland, a picture-book cluster of half-timbered, ‘black and white’ medieval houses, features regularly in competitions such as Herefordshire in Bloom and Best Presented Village; presumably the judges of such competitions would be gently dissuaded from venturing over the small bridge at one end of the village, beyond which stands the fourteenth-century Staick House, until recently all but uninhabitable following several decades of neglect. It was here that my father spent the first four years of his life, and where his cousin Francis – known to everyone locally as Mush – was still living.

Despite various online posts lamenting the house’s abandoned state, the village shop were quick to reassure that despite appearances it was still very much inhabited. My first mistake was to approach the house by the front door, marking me out as a passing tourist at best. Only after

several attempts – I should keep trying, Mush keeps odd hours, they encouraged – did I detect signs of life, only to be told in no uncertain terms that no, he had no relatives, not even distant ones. Explaining who I was, or rather who my father was, seemed to register, though the door remained shut – permanently, as it turned out – and I was directed round to the back of the house.

If the front door was seldom if ever opened, the back kitchen door was rarely if ever closed, even in the depths of winter. Though Mush lived entirely alone (his mother, a noted beauty and fashion model in her time, had died in childbirth, leaving him to rattle around the house on his own for the best part of ninety years), he was no hermit, with a large blackened kettle kept permanently on the go for anyone who cared to drop by, and a hundred or so (unwashed) mugs crowded onto the kitchen table, amongst, around and through which a resident mouse happily went about its way – to which Mush paid no attention either then or on any of my subsequent visits. Washing up involved a flick of the wrist to dispatch any dregs through the open doorway, followed by a cursory wipe with a page of old newspaper – only for me, a privilege not extended to his own mug or anyone else’s.

The last time my father had been to the house would have been when he was at Cambridge, Mush seemed to think. Though just a boy at the time, he remembered how everything and anything electrical or mechanical had been got out ready for his cousin’s visit – ‘he could tell what was wrong just by looking at it’ – pointing to a primitive wooden wireless cabinet, presumably still left out in the hope that he might drop by again some day. Certainly his Eardisland relatives had always assumed that he would end up doing

something technical, become an engineer of some sort perhaps, given that he’d always been tinkering with wireless sets and suchlike from an early age. They thought that was what he was doing at Cambridge, so if anything they were disappointed to hear later that he’d ended up in ‘the Foreign Service’.

But he never did drop by again, leaving everything and anything electrical or mechanical to remain where it was gathering dust, and that was pretty much the last that his Herefordshire family heard of him. Worried that my trip had been a wasted one, Mush suggested I might want to see my father’s old bedroom before I left – though he doubted whether there was anything of his still in there, not that he’d been inside it for a while (Mush- speak for several years).

In the short time I’d been at the house I’d seen enough to suspect that the room was unlikely to be preserved Brontëlike exactly as was, but even so . . . Just finding my way to the staircase required negotiating decades of debris, all left lying where it fell. With no electricity, what little light there was came courtesy of mice having chewed through the curtains and the garden having long since broken and entered through the house’s mullioned windows: what in the half-light looked like ivy-patterned wallpaper turned out to be ivy-covered wallpaper. Additional random hazards included missing floorboards, a grandfather clock lying flat on its back with its innards spread out mid-autopsy, and a huge, menacing wooden propeller overhead (Mush had an aeronaut uncle famous for having been the first man in England to fly upside down). Only the full-size billiard table in the next room held out the possibility of ever being brought back to life, should anyone think to clear the ceiling from its surface.

Feeling my way up the windowless staircase – which wound its way around the pipes of, eccentrically, a church organ – I passed by Mush’s bedroom (not for the squeamish), then angled my way along a sloping corridor. Since doors had a habit of jamming, sometimes for years on end, he’d armed me with a hammer, though in the end a shoulder was all that was needed, opening up a small, square room unexpectedly filled with sunlight. But sunlight was all that it was filled with. No carpet, no furniture, not even wallpaper (mice again) – just a mound of yellowed newspapers and magazines gathered up bonfire-like in the centre of the room, out of which poked a few faded blue struts of a child’s cot.

And so I came away from Eardisland none the wiser. Back to where, for my part, this story really began: my own early childhood. Not that I had much to go on here either. Just a snip of blue ribbon and a tuft of downy hair, a dozen or so greetings cards (mostly storks carrying baby-bundles) and a My First Year album – in which my father noted that I looked like his own father – though My First Two Months would have been more apt, since the remaining months are all crossed out by a diagonal biro line. I also have several boxes of family photos, yet somehow just a single one of me as a baby.

Home was a rhododendron-lined street near Woking where we’d moved shortly before I was born, bringing with us the latest in a long line of duffle-coated au pairs, hired in the hope that they might spoon-feed my brother (and the soon-to-be me) a little of their German or, more recently, Finnish, depending on which country our father was being posted to. But his Helsinki posting had come to an abrupt

end, followed by an equally abrupt departure from the Foreign Office, or more exactly the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS). He’d taken a job in Belfast to tide him over, returning in time for my birth, but then one sunny July morning, as I lay on a blanket in the back garden, my mother stretched out on the grass beside me, he’d leant out of an upstairs window and called down to say that he was just going out for a loaf of bread and might be a while.

It would have been quicker to take the path through the woods at the back of the house, but since he’d various other bits and pieces to see to, in the end he decided to take the car. And my brother. And discreetly tucked two passports into the glove box. His route probably took him past the local bakery, but he didn’t stop, heading for, well, who knew where. The other passport was my mother’s, taken so she couldn’t follow.

The police advised that he had likely returned to Belfast, but as the days ticked by and with still no clue as to their whereabouts, she approached her former employers for help, taking the train up to Waterloo every few days to update them. But – officially at least – SIS was not in the business of tracking down ex-employees, still less interfering in their domestic affairs. Only when our pale-blue Vauxhall Wyvern turned up in Southampton Docks car park did anyone think to check through the various ships’ manifests, which duly revealed husband and son as having embarked on the SS Homeric , which had set sail for Montreal that same evening.

As it turned out, her desperate commutes up to town were not entirely wasted. On one such journey she’d found herself sitting next to the local conveyancing solicitor who’d overseen the purchase of her house, who agreed to

act on her behalf – and who eventually managed to track down her missing son. And with that off she set, replacement passport in hand.

A few months later and there I am, on that same blanket, on that same patch of grass, looking quizzically over at my new-found brother as he looks quizzically down at me. As well he might.

I, of course, knew nothing of all this. Nor would I, certainly for a good few years yet, and even then only the bare facts: it would take half a lifetime to fully unravel the events of that July morning. But then I had more than just family secrets to navigate.

‘Next week we are going sailing with the Shergolds.’ June 1964.

Mother’s (modest) SIS salary meant we could finally afford a new car. Which is to say, a very old car, August 1966.

Aunt A (Agnes Miller), c.1955, also ex-SIS.

2. Woking

‘I may be going back to “the office”. Don’t faint.’

Mother, letter to Aunt A (also ex-SIS ), March 1966

As luck would have it, our mother was not the only party to have taken an interest in the whereabouts of her errant husband. Unlike their fictional counterparts, the Russians went about their business with a refreshing lack of cloak or dagger, occasionally dialling the heavy black Bakelite phone in our front room, Woking 4786, and asking where he was. Apparently they had ‘an agreement’, which, true to form, he had not adhered to. Undaunted, my mother batted back their enquiries. She had no idea where he was, but should they have more success than she was having, perhaps they would be so kind as to pass on the relevant details?

Her own motives for tracking down her husband were rather more straightforward. Despite having been one of the Foreign Office’s ablest linguists, fluent in several languages, he had a curious blind spot, seemingly unable to master the word for ‘alimony’ in any tongue – leaving her to bring up two small boys single-handed, which along with the expense of retrieving my brother and endless legal fees (we were being made Wards of Court) had long since exhausted any

savings she may have had. A retired army brigadier and his wife across the road helped out with a little typing work here and there, but for us the make-do-and-mend years were set to last a while yet: ‘He has James’s vest and pants, J’s trousers and shirts, Timmy’s sweater, J’s coat and football boots, and a cap (too big) belonging to an old boy’ – supplemented by the occasional woollen jumper knitted by her aunt on the No. 14 bus up from Putney.

As soon as I was old enough for school she took a parttime job with a local engineering firm, the money welcome, the routine less so: ‘The work goes into the “In” bin, you bash it through and then fling it in the “Out” bin. Only four of us (out of fifteen) admit to shorthand, the others have more sense.’ But if her Woking existence was a far cry from her Berlin days, no one was any the wiser. ‘I made few friends, as it was all too difficult to explain.’

If anything, it was the house itself that shed a little light on her former life, and piece by piece, find by find, introduced us to our father, John Bryan Wood. Or JBW, as he was called by one and all, family included. The endless Russian, Finnish, Swedish, Norwegian, Spanish and German language books; the camera equipment stashed away under the eaves; stacks of coins on a high shelf which, much like a ‘Penny Falls’ arcade machine, would trickle down if nudged hard enough (though the bank wouldn’t change foreign coins, certainly not East German coins). Most obviously it was our garage, with his workbench still much as he’d left it, covered in mounds of sawdust caked to a hard crust. In icy weather we’d sprinkle some of the sawdust across the driveway, but as we dug deeper we came across shards of brown glass, the remains of dozens of lozenge-shaped radio valves, some still with their original

filament wires – hardly ideal gritting material – along with several biscuit-tin lids onto which clusters of metal components had been soldered: cup-shaped objects resembling the top half of a bicycle bell, with various wires and hollow cylinders, all coated white by corroded batteries. Above the garage was a small attic space which, as we grew taller, eventually came into reach: balancing on my brother’s shoulders, as he in turn stood on a chair, I’d hauled myself up into the darkness where, spreading myself flat to avoid falling through the joists, I uncovered two shotguns hidden under the thick strips of orange-yellow lagging. Our enthusiasm for such finds, a steady stream of which continued to turn up throughout our time in the house, was not shared by our mother – they were all promptly confiscated never to be seen again. Much like their original owner. Though out of sight he was not entirely out of contact, even managing the odd birthday present down the years, if nowhere near our actual birthdays: a five-dollar bill; a model Phantom jet airplane; a miniature chess set; even a gold Omega watch, housed in a smart pale-blue box – which I would need to take good care of, his handwritten note cautioned, as it had been handed down from his own father. All these would arrive in envelopes and parcels plastered with blocks of improbably exotic stamps from the likes of Hong Kong, Iraq, Indonesia, Canada, the US and Vietnam. Clearly, wherever our father was, and whatever he was doing, he was leading a rather more colourful existence than that of a parttime secretary in a local engineering firm. But that was about to change.

Ironically, the Russians had unwittingly done our mother a favour, their phone calls elevating her troubles above the

merely domestic and gradually ushering her back into the fold. As well as occasional lunches and sailing trips with Shergy and Bevis, every so often (thankfully not too often) her fellow ‘ex-Berliners’ would descend en masse to dispense gin and sympathy, their raucous laughter penetrating up through the floorboards. Summoned (a shrill whistle up the stairs) to put in an appearance – best to get it over with – I’d sidle in to where they were all sitting, my mother as usual slumped horizontally in her armchair, feet flat against the wall, skirt hitched up, holding forth as they took it in turns to ruffle my hair, after which I was free to escape back up to my room.

Eventually, word reached her that ‘Registry’ – where SIS stored all its files – were looking for people to help lighten the load. Given the nature of the material, the position was only open to ex-employees, on the basis that they had already proved themselves entirely trustworthy. Unfortunately her application suffered from her husband having been dismissed from SIS for being entirely untrustworthy. As a result, after the usual security checks ‘yet more security checks’ were needed, before eventually Tru in Personnel was able to confirm her return (a word or two from former boss Shergy likely seeing her over the line).

The job title would be Junior Executive, Tru cautioned, which my mother took to mean ‘another word for clerical no doubt, but anything will be a relief from engineering’ – and with that she was back with ‘the office’, which was now ‘a very different kettle of fish, new, hardly recognizable,’ she wrote to her aunt. SIS had moved from its rambling Broadway headquarters near St James’s Park to the suitably nondescript concrete and glass of Century House, a tenminute walk from Waterloo Station. ‘Not a patch on the

old rabbit warren, but nice to have a window.’ Her husband need never know. Nor, in all probability, did the then head of SIS , who a decade earlier had ordered her husband’s dismissal.

Registry had by this time become little more than a dumping ground, choked with an ever-mounting back catalogue of records, leads, reports and personnel files – which in those far-off, pre-digital days all had to be sorted, indexed and filed away by (entirely female) hand. ‘Twenty-odd – and I mean odd – women to check the work off. Vapours and moods on all sides,’ with a backlog of ‘hundreds of files, cupboards overflowing with work, and with just one doddery seventy-year-old to do it.’ Though likely as humdrum as it was hush-hush, the job was not without its perks – ‘I collect the scraps from the canteen for the cat. I think folk imagine I carry them home for the boys’ – while the salary, though modest, meant that she could finally afford a new car, which is to say a very old car, even the occasional luxury: ‘Went berserk – bought myself a new dress.’ On the last Friday of the month, payday, she’d head across Waterloo Bridge for dinner at the Savoy Grill with her ‘office’ chums, supplemented by the occasional outing a little higher up the SIS food chain: ‘The chief and his sidekick are going to be there so I hope to make an impact – if I can’t do it in tomato trousers I shall never do it.’

For the next five and a half years she took the 7.57 up to Waterloo, then walked down to Century House (‘office tel. 01 928 5600, x 498’). ‘I can relax and put my feet up in warmth and comfort, drink at the bar with civilized human beings, Communist or not, and eat meals which don’t have to be prepared or washed-up after. Bliss,’ she wrote to her aunt, before arranging to meet ‘for a proper natter over a sticky

bun behind Waterloo Station’ to update her with chest and arm measurements for my brother and me in time for our Christmas jumpers.

Theirs was a shared history: her aunt had introduced her into SIS the first time round. It was standard practice for the vast majority of secretarial staff (with rare exception, the only position open to women at the time) to be recruited via family, though unlike most, my mother and her aunt were not from the well-to-do home counties set or a senior armed forces family – far from it.

My mother was born in Glasgow, the daughter of a local insurance manager, and though they soon moved south she retained a little of the language, if not the accent: about was ‘aboot’, trousers were ‘breeks’, while in those more innocent, early days ‘blether’ simply referred to the tall tales and exaggerated stories that all young girls and boys like to tell. Home from the age of twelve was in the seaside town of Whitley Bay, a suburb of Newcastle, where she attended the local Monkseaton High. Like many girls of her background, her horizons didn’t extend much beyond the local secretarial college (opting against Durham University), somewhere along the way acquiring a young submariner boyfriend. But the safe if rather predictable path she was starting to tread came under intense pressure every summer with the visit of her Aunt Agnes. It was never quite clear exactly what her aunt did, still less how she had come to be doing whatever it was she did. All the family knew was that she had spent most of the war in Cairo, spoke a little Arabic, had learnt to ride (camels) and, when not knitting jumpers for the offspring of Embassy staffers stuck in draughty English

boarding schools back home, busied herself arranging travel permits for the likes of Freya Stark and, less enjoyably, dealing with the explorer St John Philby. Philby was renowned as the first European to have crossed the forbidding Empty Quarter; he was a Muslim convert, trusted adviser to Ibn Saud (the future ruler of Saudi Arabia) and by all accounts – including her own – a difficult man. No doubt she gave as good as she got. Aunt Agnes was an acquired taste, with the unfortunate combination of an independent mind lacking independent means, and had long since decided against sacrificing a life of adventure on any marriage altar, which would have meant giving up her job with the Foreign Office. Or, more accurately, with Middle Eastern Intelligence.

Auntie’s rescue mission saw my mother exchange Whitley Bay for a hostel on South Kensington’s Cromwell Road, the move made easier by the unexpected demise of her submariner boyfriend (someone having forgotten to close off a valve while his submarine was in dock). Despite the hostel being ‘supervised by an old dragon of an SIS matron who was supposed to keep them out of mischief’, it didn’t stop her enjoying the full merry-go-round of dinners and dances, likely a step up from Whitley Bay’s Rex Club. With the possibility of a foreign posting for the lucky few, she honed her Pitman shorthand and signed up for evening classes at the nearby Institut Français. Having been the only girl in the hostel who had never been to London, she now found she was one of the few who had never been to Paris. Nor would she. A few weeks later she was sitting up on deck crossing over to Hamburg, then heading down to the small spa town of Bad Salzuflen where, in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, SIS had set up its German headquarters.

After an all-too-brief induction course, the not-yet-twentyone-year-old Margaret Miller, very much the young ingénue, boarded the overnight train to Berlin with its blacked-out windows, arriving – after endless checkpoints – at the epicentre of the Cold War.

Quite how her aunt, Agnes Miller, had been recruited was always something of a mystery, but it was all the more surprising given her unpromising start in life, having been orphaned at a young age and packed off from her native Glasgow to live with a distant relative in South Africa. The Agnes that I knew as a boy (always referred to simply as Aunt A) was already well into her sixties and had long since left SIS , emerging unscathed but for a frozen (palsied) right hand, most likely from having had an ice-cold gin and tonic clamped to it for several decades. Her (meagre) pension meant that she was still putting in the hours as a part-time secretary in the BBC newsroom, invariably volunteering for the less popular slots – night shifts, bank holidays, Christmas Day – time-and-a-half money, which she would splurge on our annual outing to Leicester Square cinemas or the Bertram Mills Circus. ‘When the boys write their memoirs, I am sure Auntie’s treats will have a chapter to themselves . . .’

With her pleated skirts and heavy woollens, she must have cut an incongruous figure among the denim-clad, longhaired backroom staff of the 1970s BBC , but then she must have cut an equally incongruous figure in the Foreign Office of the 1930s, her accent more Clyde than Tweed, a thorn – or thistle – among debs. But a little night-school Arabic had been her passport to a wider world, even if it meant having to share a cabin with ‘Elizabeth C-B, a rather silly girl I travelled to Cairo with’.

‘Cairo at that time was truly a Paris of the East, and to me it was paradise. Perfect hot climate, a comfortable way of life, breathtaking women,’ wrote one of her (male) SIS contemporaries. It was paradise for Aunt A too, if for rather more aesthetic reasons, meeting the likes of Wilfred Thesiger, Freya Stark, Lawrence Durrell – and an inebriated Winston Churchill. As the war turned in the Allies’ favour, she moved up from Alexandria to Baghdad (paying to have Gertrude Bell’s gravestone cleaned) and then across to Tehran, enjoying – or enduring – an overnight bus trip sat alongside one Hossein Alā, future Prime Minister of Iran: ‘I knew more about day-to-day living, he knew more about the quirks of the English language. The night and day we spent together was one long horrid pun. He loved them.’ She ended up in Damascus at the end of the war, only to volunteer for the next conflict: ‘I was in Jerusalem in 1946–7 [. . .] the walls were lined with Palestinian Police with walkie-talkie sets and tommy-guns. I suppose it was the ugliest-looking precautions I saw in all my riots. I don’t like these tommygun things.’

Given the choice, she would have opted to stay in the Middle East, but soon enough she was criss-crossing the Iron Curtain, from Istanbul to Belgrade, running into Durrell again: ‘When we were in Belgrade he didn’t write much that I know of’; to Budapest, where the Embassy bar opened ‘promptly at 5.30 so that the staff could get together and bring a little brightness into their enclosed Iron Curtain lives’; to Vienna, ‘in a flat owned by a Countess who had done three years hard labour in Switzerland for spying for the British, but it hadn’t soured her apparently as she was always keen to let her flat to Embassy people. But cold, my God, how I suffered’; to Trieste, arriving in time for the 1953 Coronation

celebrations held in the Duino Castle overlooking the Adriatic, only to find herself being mistaken for an Italian, despite her platinum-blonde hair: ‘Kept being shepherded into the Italian groups at the party and had great difficulty in getting back to my buddies . . .’

And then there was Warsaw.

I have a letter posted to her from a ‘Room 9’, confirming that ‘some of your overseas service ranked as unhealthy service’. Nowhere more so than Warsaw. She’d been helping distribute food and clothing parcels via local Catholic churches – possibly hoping to pick up a little word-onthe-street low-level intelligence in the process – only for her contacts to be taken away one by one for questioning. Even in a country boasting 36,000 government agents, who in one (busy) night shift had arrested some 5,000 ‘suspects’, this seemed more than coincidental. Only when she stopped putting her expenses through the books, opting instead to use her own money, did the situation improve, prompting her to think the unthinkable: that someone within the Embassy might be a ‘fellow traveller’ (as she termed it). A slippery slope that, rightly or wrongly, began to imbue her with a distrust of the service itself. Rightly, as her diaries would later record, when not one but two of her former colleagues were unmasked as double agents. ‘I was in Beirut with [George] Blake and Warsaw with [Harry] Houghton and so help me I don’t remember either of them. I do know that a damn good clean-up is long overdue and the ones they don’t sack for fellow travelling they can sling out for inefficiency.’

‘The office’ posted her back to the Middle East, ‘lent as a gulf expert’, where she ran into Thesiger again as he headed into Oman, ‘though he didn’t get permission’, and dealt with

the eccentric – ‘E, the British representative in Bahrain, twice married. The first time during the war, a Belgian. This lasted nine days as he came home one night and found her in bed with a RAF type. Now spends most of his time and all his holidays with his second ex-wife and her new husband. Odd, but then E was odd’ – and the undesirable – ‘Sarraj was head of Syrian Intelligence in my time in Beirut and a very bad man he was too. Today we are calling his enemies rebels, but if they win they will become our dear, dear friends – and so it goes. Hope the rebels win.’

By way of a thank you her farewell posting was to her favourite watering hole, Beirut, a city she knew well – well enough to head up into the hills in high summer to estivate. Estivate? ‘To live in the hills above Beirut is to estivate. Had quite forgotten about estivation allowances until it caught my eye again.’ Of an evening they’d head down to the port, more often than not calling in at The Normandy or the St George’s Hotel, where she could always count on meeting familiar faces, few more familiar than St John Philby’s son Kim, then employed as Middle East correspondent for the Observer, having left ‘the office’ under a cloud. Perhaps she had more licence than most, having known him since he was a schoolboy, but after one too many (no doubt ferocious) gin and tonics, she’d sounded off, loudly accusing him of being one of her ‘damned fellow travellers’. Not the done thing. But all was soon forgiven and forgotten, a later diary entry noting that ‘Kim’s father has died. The Sunday Times obituary seems a little off the beam and the Observer I think is the better one as it was written by Kim. What will happen to his natural wife and children now? I suppose they’ll go back to S. Arabia to the old black tents. Poor Kim, he is alone now, wife having died. The old boy was fond of his grandchildren,

and, of course, cricket. Does his real wife go into mourning or does she just ignore the affair? No mention of the family is made in the obituary. No mention of Kim.’

Of course in the end even Kim let her down, though by then she was largely beyond caring. Her diary entry for 6 March 1963 notes: ‘What a week. Aunt Betty committed suicide and Kim Philby disappeared, the whole thing in the papers on the 4th; too soon to say if Kim has taken a slow train to Moscow, he may have been murdered. That would be better than another scandal. Odd that I don’t seem to care any more, but there it is I don’t. Only glad I got out in time. “ EH ” was right when she said to me one day: “What would you do if you suddenly found you had been working for Stalin all the time?” She spoke truer than she knew. Well “I ken noo.” Still, I wish it had been anybody but Kim.’

But by this time Cairo, Alexandria, Baghdad, even Philby himself were already ‘like something from a different life’. Certainly as far as anyone in Room 3051 of Broadcasting House knew she was simply ex-Foreign Office – and the nearest her diaries come to any mention of the Cold War is a walk up to the Soviet Embassy to catch a glimpse of Yuri Gagarin, the first man in space: ‘Much more handsome than his photographs. Just a shame he is Russian.’ There was still room for the occasional pasted-in obituaries of Foreign Office mandarins and Arabists she’d known, but even these tended to be sandwiched in among waspish observations on the drinking habits of the newsroom’s male presenters (‘John as drunk as a coot on the last night of the shift’) or the unsuitable marital choices of its female presenters (‘Pretty girl, small, smart and elegant, throwing herself away’). Where once she had splashed out on front

stalls seats in the opera houses of Vienna and Trieste, now she was reduced to traipsing down to Covent Garden at the end of a night shift to queue for rehearsal tickets, her salary just about enough to ‘keep a roof over my head, however leaky’. And though she remained in touch with one or two former ‘office’ colleagues, she avoided get-togethers and reunions, tarnished by her Warsaw experience, seemingly seeing her so-called fellow travellers everywhere she looked. Not least within her own family.