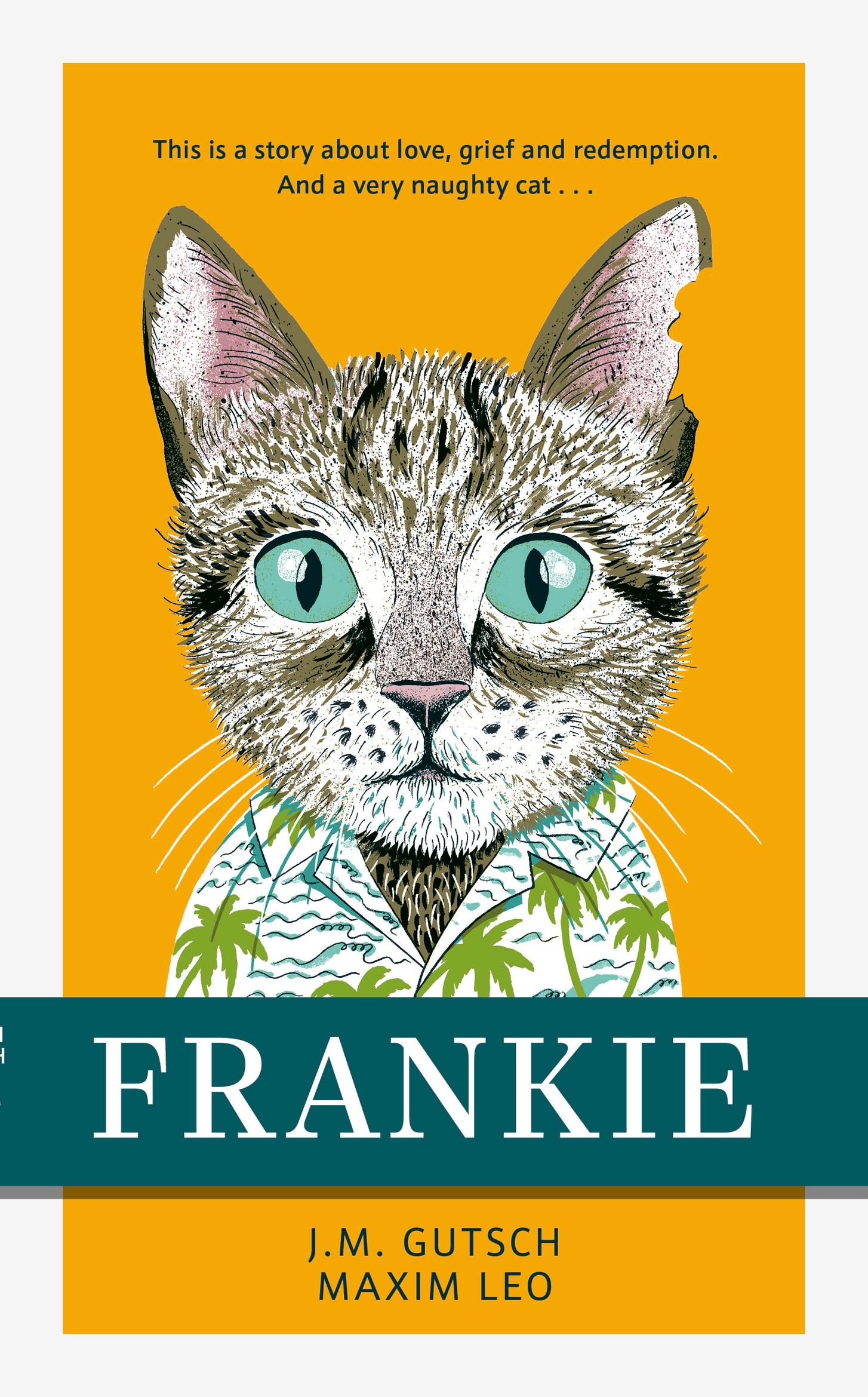

j. m. gutsch and maxim leo

Translated by Sharon Howe

PENGUIN MICHAEL JOSEPH

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Michael Joseph is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW

penguin.co.uk

First published by Penguin Michael Joseph, 2024 001

Copyright © Jochen Gutsch and Maxim Leo, 2024 English translation copyright © Sharon Howe, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Set in 12 5/14.75pt Garamond MT

Typeset by Falcon Oast Graphic Art Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn: 978–0–241–71268–9

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper

‘What makes life so difficult?’ ‘People?’

An Affair to Remember

1. The Piece of String

I’ve been told you should always tell a story starting from the top. Or the beginning. But being a tomcat, I know nothing of tops or beginnings. Humans have all sorts of rules for how life should be. They’ll order you about: ‘do this, do that!’ Sounds like a bit of a drag if you ask me. Too much like hard work, and hard work has never been my style. So I’m going to start any old where. It might just happen to be the top. Or the beginning. It was the nice time of the year, and by that I mean the time when the evenings were warm and long and bees were buzzing in the lime trees. On one of those evenings, I decided to pop over to the Professor’s. I’ll tell you more about who the Professor is later: he doesn’t make an appearance in our story for a while.

There I am, trotting along the Big Road that goes through the middle of the village. Past the lake, where the grass is high and I stop to eat a few grasshoppers. D’you know what I love about grasshoppers? They never complain when you eat them. Not like birds. Birds always make such a fuss. ‘Ooh, don’t eat me! I’m a mother, with ten babies in the nest!’ they’ll cry. So over the top. But it catches me out every time, old Muggins that I am. Really puts a dampener on your appetite. I’m left standing there with a mouthful of bird and – for

a moment or two – a guilty conscience. And then the moment passes.

So on I go, past the village church, past the ramshackle birdhouse, past Fatty Heinz the Rottweiler’s vile-smelling pee, past two compost heaps with nothing decent to eat on them, not even anything halfway decent. Just coffee grounds, eggshells, potato skins and apple peel. Humans, let me clue you in on a little secret. A compost heap made of nothing but peel makes you look cheap. On I go, past the big sandhill just before the wood begins and beyond which the world ends. I’m in good spirits, strutting along all cool and calm in the evening light. When I get to an old wooden fence, I slip through it and into the garden of the Deserted House. Everyone calls it the Deserted House because one day the people from the city who used to spend every summer there stopped coming.

All the windows are closed and the curtains drawn, and in winter the wind howls all around the house. Fatty Heinz (who’s a certified moron, by the way) has heard the noise and thinks there’s a pack of werewolves living there.

But something odd is afoot: I’m nearly past the Deserted House when I spot a man inside the house! Utterly spooked, I crouch behind a bush and hide. Talk about getting the heebie-jeebies! While I’m sat there, another thought crosses my mind: Well, shit, Frankie. What happens now?

I’m tempted to run straight back home and tell everyone I know the big news. But I also know the inevitable

inquisition that would follow. ‘What did the man look like, Frankie?’, ‘What did the man smell like, Frankie?’, ‘What’s the food like at the man’s place, Frankie?’, ‘Are you quite sure it wasn’t a werewolf, Frankie?’

When an empty house is suddenly no longer empty, all sorts of questions bubble to the surface. Everyone wants to know more. And if you can’t give them any details, you’re the one who ends up looking stupid.

So I do what any tomcat worth his salt would do in these trying circumstances: I stay put, and I peer out from behind my bush.

Listening. Looking. Listening. Looking.

(This went on for quite a while so I’m giving you the abridged version.)

Listening. Looking. And so on.

Then I creep closer – ever so softly – and when I’m within a few cats’ tails of the big window I peer in and begin to gather clues.

Clue 1: There really is a man in there.

Clue 2: The man is standing on a chair.

Clue 3: There is a string hanging from the ceiling.

Clue 4: The man is wearing the string around his neck.

Clue 5: Further to Clue 4, the string is very thick.

No kidding, I’ve never seen such a whopper! I’m a

string connoisseur, you see, so I would know. And I’m telling you, this string was the bee’s knees. When I lived with Old Mrs Berkowitz, we used to play with the stuff nearly every day. There was never a human on the end of it though, only a mouse sometimes – not a real one of course, just a woolly one. (Humans seem to think we cats are fooled by this, but for the record, we’re not. We’re not stupid.)

So when I see this beauty, I’m suddenly reminded of Old Mrs Berkowitz and the best time of my life . . . which sadly didn’t last very long. It ended when, one day, Old Mrs Berkowitz lay down abruptly in the garden and two men arrived soon after – all in white – bundling her into a big car with flashing lights on the roof. I never saw her again after that.

Remembering all this gives me a funny sort of ache in my heart, and I’m tempted to call out to the man: ‘Hey, you there! Playing with the string! That’s a beautiful specimen! Can I play too?’

But I know I mustn’t say anything.

Instead, I pluck up all my courage, jump on to the window ledge and peer inside. The man is standing on a chair with the string around his neck. Then he sees me, and looks surprised. He certainly doesn’t seem pleased to see me. He actually seems rather angry. He opens and closes his mouth like a carp, saying something to me, but I can’t make out what because – to state the obvious –he’s behind the windowpane and I’m in front of it.

So instead, I start my blinking routine. Humans, here’s another hot tip: when a cat blinks, it’s a bit like smiling.

Blinking translates as: hey there, amigo, everything’s cool. I’m good, you’re good. Wassup? I’m blinking manically at the man through the window, but he seems to have about as many brain cells to rub together as Fatty Heinz, and doesn’t catch my drift.

Instead, he waves his arms around in my general direction. I raise my right paw to say: Hey, no worries! I understand. I know better than most that it’s easy to get carried away when you’re playing with string. Though to be honest, the whole arm-waving business looked a little odd. I lick my privates for a bit to calm my frazzled nerves.

What happens next happens quickly. The man lets go of his string and jumps down off the chair, and within seconds, the door of the Deserted House flies open. He reaches for an object of some sort and hurls it at me. I skedaddle, but I’m in shock and my legs go all wobbly! I see a shadow approaching. Something’s chasing after me and pounces on my head.

I don’t remember anything else after that.

The next thing I know, the wind is whispering something to me. I strain to listen but can’t make out what it’s saying. I’m lying on the lawn in front of the Deserted House, worn out and motionless. I can hardly open my eyes. And the wind keeps on whispering, until I realize it isn’t the wind after all. It’s the man bending over and speaking to me. He nudges me with his foot, as if I’m a dead rat or something. ‘You all right?’ he asks. It’s a rather stupid question if you ask me, seeing as how I’m

very obviously not all right. I’m so exhausted that I fall right back to sleep.

When I come around again, I don’t know where I am at first. I’m feeling rather woozy, and I peer around warily. Then I spot that marvellous string hanging from the ceiling, and my memories come flooding back to me. I’m inside the Deserted House! On a couch, to be precise, with a newspaper spread under me and the man now sitting opposite me in an armchair. He’s holding a tiny telephone to his ear and is talking agitatedly to someone. I might have no idea who he’s talking to, but I can tell you what he’s talking about: yours truly.

Speaking into his telephone, the man says: ‘I’ve got a dead cat here. Can you drop by? Yes, she really does look very dead. But look, I’m no vet, so that’s why I’m calling. No, she’s not my cat! I’ve no clue who it belongs to. What does the cat look like? What does that matter? It’s a cat! Grey tabby coat, a bit mangy, with a lump out of one of its ears. No, I don’t know how she died! Yes, I found the cat in my garden. Listen . . . OK, my address is . . . No, the cat . . .’ ‘Ttmmcctt!’ I slur.

That was obviously a bad move. The Professor (who you’ll meet later) is always saying I should be a little savvier – more tactful – or else I’ll get myself into trouble one day.

But I was feeling pretty peeved, to be honest. First, I’m nearly clobbered to death. Then, to add insult to injury, this human keeps referring to me as a molly, even though I’m clearly a full-blooded tomcat!

‘What?’ the man asks.

‘Ttmmcctt!’

My Humanish is a bit . . . sluggish ? And whatever whacked my head has made me dizzy. I have to keep repeating the words over and over until finally I can say with perfect diction: ‘I’m a tomcat!’

The man gawps at me as if I’m some kind of alien.

In my experience, whenever a cat decides to speak, humans behave downright bizarrely. Every. Time. Without fail! That’s why I gave up speaking long ago. The last time I spoke was outside the village shop. Something fell out of this woman’s shopping bag, so I say, ‘Excuse me, madam, but are those your Hoover bags?’

And lo and behold, she took off screaming. I could hear her yelling all the way down the high street! Not the brightest spark, it seems.

Humanish is dead easy. The first word I ever said was snow. And then I picked up more and more. A lot of the animals at the shelter spoke Humanish, and so did Old Mrs Berkowitz, and so did her TV.

I used to speak Humanish better than Cattish.

Nowadays I can speak about ten languages. Which isn’t all that many. The Professor speaks twenty-seven, even Goatish, which almost no one speaks. Other than goats of course. As a cat, you’re basically stuffed if you don’t speak any foreign languages. Do you want to know why? Biodiversity! Wherever you go, you come across other animals with other languages, and not all animals are the kind you can eat, or tear in two, or torment to

death. So you have to resort to talking. It wasn’t my idea: that’s just the way it is. Say I’m walking through the woods for instance. There’s this giant owl there who spends his whole day sitting on a branch, with a face like a wet weekend. So I always like to strike up some friendly conversation in Owlish to lighten the mood.

‘Hey, Owl. How’s it hanging?’

‘Mustn’t grumble,’ Owl replies.

‘Yeah, mustn’t grumble.’ I nod. ‘Keep your pecker up!’

‘Right you are, Frankie!’

And just like that, you can exchange pleasantries with all sorts of animals, even with an owl who does nothing but sit on a branch all day long. Humans are the only ones who lose their minds when I speak.

Anyway, back to the man in the Deserted House.

There he is, still gawping at me, muzzle wide open. I can smell that he’s scared out of his wits, and I can see the cogs in his mind turning. Just keep your mouth shut, Frankie , I think to myself. Bide your time . That always freaks humans out. Because then they start to wonder whether they’re imagining things. ‘Did that cat really just speak?’ they ask themselves. ‘Is this real? Or am I losing my mind?’

The man stares at me for quite a while. Then, when nothing happens, and I say nothing, he leans back in his armchair with a sigh of relief and shuts his muzzle again. He shakes his head and exclaims with a smile, ‘What nonsense!’

‘Oh no, it’s not!’ I reply.

This time, the man really loses it. His face goes as white as a deer’s bum, which I must admit, I did enjoy a little. Well, more than a little if I’m being honest. It’s always better when a human understands what you’re capable of, or else you’re never safe from them. They might even kick you or throw things at you. Now, at the very least, I had earned this man’s respect.

A pause. Then in a flurry of confusion, the man yells, ‘YOU CAN TALK?’

Congratulations , I think. Top marks for observation. He then proceeds to speak to me very loudly and very slowly. I once watched a film with Old Mrs Berkowitz where one group of men was sitting around a fire talking to another group of men with painted faces and a collection of feathers on their heads. They did exactly the same thing. I mean, the first ones spoke to the feathered ones as if they were total dimwits.

Tapping himself on the chest, the man says, ‘ME. RICHARD. GOLD.’

This behaviour seemed pretty odd to me, but something about it was funny too. So I turn to the man and tap myself on the chest. ‘ME. FRANKIE.’

‘YOUR HEAD. HURT? OUCH?’ he asks.

‘YES. OUCH-OUCH!’ I reply.

‘ME. SORRY,’ he says.

We fall silent, and the man doesn’t seem to know what to say after that. Then he reaches out tentatively and lays his paw briefly on mine, saying ‘YOU. NO. WORRY.’

That’s a nice touch. And since he’s being nice, I figure

there’s no point beating around the bush. We might as well get down to business.

‘MUNCHY-MUNCHY? HUNGER!’ I tell him.

I point to my belly and my mouth.

Reassuring me, he replies, ‘MUNCHY-MUNCHY? YOU? I FETCH FOOD!’

And if you ask me, those were the first sensible words the man named Richard Gold had spoken.

2. Frankie Boy

Just so you know: from now on, I’m going to call the man named Richard Gold ‘Gold’ for short. It’s saves me time, which is just as well because this story’s a bit on the longer side and we still have a way to go. Plus, I don’t really like the name Richard. I know he can’t help being called that. But let’s face it, as names go, it’s a bit of a non-starter.

And believe me, I’ve known some crap names in my time. My mother named me Number 5, and my siblings were called Number 1, Number 2, Number 3, Number 4, Number 6 and Number 8.

There wasn’t a number 7, because my mother said it would bring bad luck. So Number 7 became Number 8, though he was officially the seventh sibling. Naturally, we nicknamed him 78 to add to the confusion.

Later, when I was living at the animal shelter, the humans there named me Milksop on account of my white chin. That all but ended any hopes I had of a respectable reputation. Oh the shame! The embarrassment!

All the other animals laughed at me. Even the miniature Pekinese in the next cage – who looked like a collage of animals that have long since gone extinct –joined in.

Eventually a family with children took me away and

gave me a new name: Herbert. Or sometimes Herr Bert. They thought it funny and – excuse me while I gag – cute.

But they were also cruel, and the children were the worst of all. They’d hold a lighter to my tail for a laugh, or would throw me back and forth to each other like a ball, shouting, ‘Fly, Herr Bert!’ One day, out of sheer terror, I clawed one of the children across their face. And then I did it again. It was a rather bloody affair. I wound up back at the shelter again after that.

And everyone knew me as Milksop once more.

But just when I started to think I’d be Milksop for the rest of my life, Old Mrs Berkowitz suddenly appeared in front of my cage. She looked at me, stroked my head and muttered, ‘Milksop? Well, isn’t that a shitty name!’ She was quite the lady, but her language was often less than ladylike.

So now you know: if my lingo is sometimes a little on the coarse side, it’s not my fault. Blame the educational deficiencies in my upbringing!

Then Old Mrs Berkowitz took me home with her and spent a few days thinking and listening to a lot of music. By a man from America who she called Frankie Boy Sinatra. Let me tell you, this Frankie Boy could really sing. Not a patch on a coal tit, mind. But he was pretty decent for a human. Anyway, Old Mrs Berkowitz says to me: ‘Frankie. How do you like that name?’ And I’m like: Wow. I was blown away. I went prancing through the village, calling out to everybody: ‘I’m Frankie! As in Frankie Boy from America!’