Clive Cussler’s The Corsican Shadow (by Dirk Cussler)

Clive Cussler’s The Devil’s Sea (by Dirk Cussler)

Celtic Empire (with Dirk Cussler)

Odessa Sea (with Dirk Cussler)

Havana Storm (with Dirk Cussler)

Poseidon’s Arrow (with Dirk Cussler)

Crescent Dawn (with Dirk Cussler)

Arctic Drift (with Dirk Cussler)

Treasure of Khan (with Dirk Cussler)

Black Wind (with Dirk Cussler)

Trojan Odyssey

Valhalla Rising

Atlantis Found

Flood Tide

Shock Wave

Inca Gold

Sahara

Dragon

Treasure

Cyclops

Deep Six

Pacific Vortex!

Night Probe!

Vixen 03

Raise the Titanic!

Iceberg

The Mediterranean Caper

Wrath of Poseidon (with Robin Burcell)

The Oracle (with Robin Burcell)

The Gray Ghost (with Robin Burcell)

The Romanov Ransom (with Robin Burcell)

Pirate (with Robin Burcell)

The Solomon Curse (with Russell Blake)

The Eye of Heaven (with Russell Blake)

The Mayan Secrets (with Thomas Perry)

The Tombs (with Thomas Perry)

The Kingdom (with Grant Blackwood)

Lost Empire (with Grant Blackwood)

Spartan Gold (with Grant Blackwood)

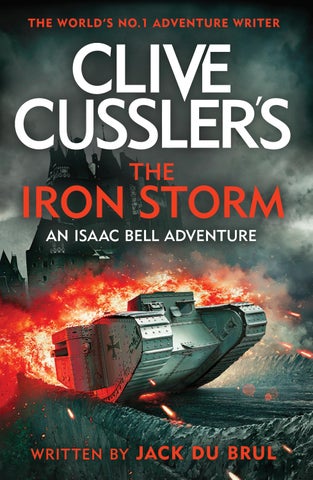

Clive Cussler’s The Iron Storm (by Jack Du Brul)

Clive Cussler’s The Heist (by Jack Du Brul)

Clive Cussler’s The Sea Wolves (by Jack Du Brul)

The Saboteurs (with Jack Du Brul)

The Titanic Secret (with Jack Du Brul)

The Cutthroat (with Justin Scott)

The Gangster (with Justin Scott)

The Assassin (with Justin Scott)

The Bootlegger (with Justin Scott)

The Striker (with Justin Scott)

The Thief (with Justin Scott)

The Race (with Justin Scott)

The Spy (with Justin Scott)

The Wrecker (with Justin Scott)

The Chase

Novels from the NUMA Files®

Clive Cussler’s Desolation Code (by Graham Brown)

Clive Cussler’s Condor’s Fury (by Graham Brown)

Clive Cussler’s Dark Vector (with Graham Brown)

Fast Ice (with Graham Brown)

Journey of the Pharaohs (with Graham Brown)

Sea of Greed (with Graham Brown)

The Rising Sea (with Graham Brown)

Nighthawk (with Graham Brown)

The Pharaoh’s Secret (with Graham Brown)

Ghost Ship (with Graham Brown)

Zero Hour (with Graham Brown)

The Storm (with Graham Brown)

Devil’s Gate (with Graham Brown)

Medusa (with Paul Kemprecos)

The Navigator (with Paul Kemprecos)

Polar Shift (with Paul Kemprecos)

Lost City (with Paul Kemprecos)

White Death (with Paul Kemprecos)

Fire Ice (with Paul Kemprecos)

Blue Gold (with Paul Kemprecos)

Serpent (with Paul Kemprecos)

The Adventures of Vin Fiz

The Adventures of Hotsy Totsy

Clive Cussler’s Ghost Soldier (by Mike Maden)

Clive Cussler’s Fire Strike (by Mike Maden)

Clive Cussler’s Hellburner (by Mike Maden)

Marauder (with Boyd Morrison)

Final Option (with Boyd Morrison)

Shadow Tyrants (with Boyd Morrison)

Typhoon Fury (with Boyd Morrison)

The Emperor’s Revenge (with Boyd Morrison)

Piranha (with Boyd Morrison)

Mirage (with Jack Du Brul)

The Jungle (with Jack Du Brul)

The Silent Sea (with Jack Du Brul)

Corsair (with Jack Du Brul)

Plague Ship (with Jack Du Brul)

Skeleton Coast (with Jack Du Brul)

Dark Watch (with Jack Du Brul)

Sacred Stone (with Craig Dirgo)

Golden Buddha (with Craig Dirgo)

Built for Adventure: The Classic Automobiles of Clive Cussler and Dirk Pitt

Built to Thrill: More Classic Automobiles from Clive Cussler and Dirk Pitt

The Sea Hunters (with Craig Dirgo)

The Sea Hunters II (with Craig Dirgo)

Clive Cussler and Dirk Pitt Revealed (with Craig Dirgo)

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Michael Joseph is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published in the United States of America by Putnam, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC 2025

First published in Great Britain by Penguin Michael Joseph 2025 001

Copyright © Sandecker RLLLP, 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

HARDBACK ISBN: 978–0–241–70810–1

TRADE PAPERBACK ISBN: 978–0–241–70811–8

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

In the midst of chaos, there is also opportunity.

— Sun Tzu, The Art of War

1March 1917

The Irish Sea

ENGLAND EMERGED FROM OVER THE MURKY HORIZON, THE line between earth and sky partially hidden by shifting bands of rain. The coast was dark and barren, but so very welcome after a stormy passage across the Atlantic that tested even Isaac Bell’s notoriously iron stomach. Technically he hadn’t spotted England but rather Anglesey Island, off the north Welsh coast, that helped mark the passage into the Mersey estuary and the port city of Liverpool.

Since the start of the war, the docks of Southampton on England’s south coast had become Military Embarkation Port No. 1 and were used exclusively for pouring men and matériel onto freighters and troopships bound for France and the front lines and for seeing the return of the countless wounded. As a result Liverpool had become the principal port for all transatlantic traffic.

Bell had been bound for Liverpool once before, but had never made it, as the Lusitania had been torpedoed as she turned northward around the southern tip of Ireland and the sheltered waters of

the Irish Sea. He reasoned that even with the Germans once again unleashing their wolf packs in the no-holds-barred doctrine of unrestricted submarine warfare, the odds of him being torpedoed twice in the same region were long enough to leave his mind at ease.

The ship he’d taken from New York was far from the luxurious Cunard liner he’d last sailed to England aboard. The Duke of Monmouth was barely five hundred feet in length and had sailed under many diff erent fl ags by even more diff erent owners in the two decades since her launching. She sported a single funnel amidships and had just four decks for passengers. The fi rst- class accommodations were on the top deck and were rumored to be adequate but dated.

For this mission, Bell was joined by Eddie Tobin, another Van Dorn detective. Like Bell, Tobin sailed on a second- class ticket in keeping with their cover. They presented themselves as the employees of an art dealer who was shipping paintings back to England for a client who’d originally sent them to America for safekeeping at the start of the war. In truth they were escorting five hundred pounds of gold bullion that had been donated by dozens of prominent New York and Boston families to help the Allied war eff ort. Once the crate landed on the pier in Liverpool their job was done.

Bell looked northward. A single British destroyer was on patrol, looking as lean and lethal as a stiletto. She seemed small and ineffective when compared to the mighty dreadnoughts the Admiralty had on hand to blockade Germany, but her four-inch deck guns and torpedo launchers were more than a match for any lurking U-boat.

A signalman on the warship’s bridge was working the handle of an Aldiss lamp, sending a coded signal to the Duke of Monmouth. Bell turned to look up toward the liner’s bridge and saw the blond woman. Like the other time he’d seen her on deck during the miserable crossing, he was struck by both her beauty and the graceful way

she carried herself, even now after enduring what must have been a week of mal de mer. She didn’t so much as look down. Bell allowed himself another moment to admire her profi le and turned back to the sea once again.

The tides on the Mersey estuary are among the highest in the British Isles and so it wasn’t too much later that the ship began to approach the river and the city of Liverpool. A black pall of coal smoke marked the distant city, far darker than the pewter sky that had enshrouded the Duke of Monmouth since leaving New York. Ship traffic on the water had noticeably increased as freighters and oilers from the United States awaited their turn to unload at the overtaxed port. More Navy ships were also present, mostly other destroyers or small armed launches that buzzed around the merchant flotilla like watchful sheepdogs attending to their flock.

After taking on a harbor pilot, the Duke of Monmouth entered the wide tidal estuary. On the left bank, the docks of Liverpool were total bedlam, with steam- powered cranes hauling pallets of cargo from countless ships’ holds and armies of stevedores trouping down gangways loaded with sacks of American grain or Indian rice or casks of Jamaican rum. Small coastal boats ducked in and around the bigger ships bringing supplies, while massive coal barges were kept in constant motion by tugs and towboats to feed the freighters’ voracious boilers.

Bell became concerned when his liner’s course kept it away from the city and along the river’s south shore. He was about to fi nd an officer to get an explanation when the chief purser appeared at his elbow. A few of the crew had been made aware of the Van Dorn detective’s mission if not the actual cargo. “Begging your pardon, Mr. Bell,” the veteran purser said with a courteous tip of his cap. “Captain Abernathey’s compliments.”

“What is it, Tony? Why are we here and not over there?” Bell asked, pointing to the busy port they were slowly steaming past.

“A freighter is still in our berth. There was a problem with a crane and it’s taking much longer to unload. Rather than have us wait, the harbormaster is diverting us to an open dock upriver a bit, near the Runcorn Gap. That’ll put us in the Manchester Ship Canal for some miles.”

Bell opened his mouth to ask a question, but the purser had an answer at the ready.

“Arrangements have been made to have your crate met just as if we’d docked in our original slot. You have nothing to worry about.”

Eddie Tobin appeared just then. Where Bell was tall and straight, with blond hair and handsome features, Eddie slouched in a poorly fitted suit and his bulging eyes and thick neck gave him the look of a frog. His head was more scalp than thin gray hair, adding to the illusion. He worked out of the Van Dorn New York offi ce, which had been Bell’s preferred station for a couple of years now, and specialized in the criminal activity in and around the city’s countless docks, piers, shipping terminals, and every other place seafarers and fi shermen could be found. Said to have salt water in his veins, he’d had little trouble stomaching the rough Atlantic passage.

“Any sign of foul play?” Eddie asked before Bell could.

“Foul play?” the purser said, cocking his head slightly.

“Sabotage of the crane at our assigned berth,” Bell clarified, “to force us to switch last-minute.”

The Englishman’s entire profession was predicated on keeping people happy and so it was clear by the look on his face that he didn’t know the answer to the question and hadn’t thought to ask it himself. “I, ah . . .”

“Doesn’t really matter, Isaac,” Eddie reminded his boss. “Our

job’s done when the crate’s off this tub. What happens to it here is on the local boys, not us.”

“Call it a professional courtesy,” Bell said.

“We’ve got some time,” Tony the purser said. “I’ll have the wireless operator signal the harbormaster again and fi nd out what exactly happened to that crane.”

Bell considered the offer and despite having no stake in the crate’s fate once on English soil, he agreed and sent the man off to the radio shack.

“You don’t ever quit, do you?” Eddie remarked, resting his arthritic hands on the rail.

“I don’t have it in me,” Bell agreed.

“And that’s why you’re old man Van Dorn’s chief detective and I’m still grubbing around the docks like some greenhorn.”

Bell chuckled.

At Eastham, a short distance upriver from Liverpool, the Duke of Monmouth entered the Manchester Ship Canal through a tightfitting set of locks. Such was the state of the tide that they needed to only be lifted a couple of feet before the water in the lock equalized with that of the canal, which, when it fi rst opened in 1894, made the city of Manchester an actual seaport, though it sat some thirty miles from the coast.

More fi rst- and second- class passengers were coming out to the decks to take in the sights now that the ship was no longer tossing them about. Many still looked a little sickly, but most had color returning to their cheeks and obvious relief in their voices as any threat of a submarine attack was well and truly over.

The canal hugged the southern bank of the Mersey River, which remained busy with the tide still up and the sandbars and shoals buried deep under the water. At low tide, much of the estuary was a

great mudfl at that, in the right conditions, could smell something awful. At points the canal was narrow enough that it seemed they were sailing through earthen fields rather than on water. Bell felt he could lean over the rail and pluck a skeletal branch from a tree growing on the berm separating the canal from the river.

A detective all his adult life, Bell relied as much on instinct as he did on intellect, both of which he honed to a keen edge with every opportunity. He loved what he did and was therefore very good at his job. His instincts were telling him something his intellect said was unlikely, but he listened to his gut all the same. He turned around and looked up to where the fi rst- class passengers were enjoying their superior view of the Lancashire countryside. He caught the blond woman watching him. He smiled as he saw a slight blush against her alabaster skin. Bell tipped his hat and she flustered for only a moment before regaining herself. She turned away with a look that managed to elevate her haughtiness to some form of high hauteur.

That brief exchange quickened his pulse the same as the fi rst time he’d seen her.

Quickly though, reality intruded as a noxious smell enveloped the liner in a cloud that sent multiple passengers back into the salons and reception areas.

“Lord, that’s awful,” Eddie remarked. This from a man who’d once sorted through several tons of rotten oysters to fi nd a gun used to kill a dockside security guard.

The Duke of Monmouth had passed around Weston Point and was approaching the docks at Runcorn. They were about nine miles from the sea. The air was heavy with coal smoke and the other odors of the industrial revolution, but atop it was the farm smell of animal

manure, which was somehow much worse, like the noisome discharge of a diseased herd already in the throes of death.

Another ship was tied to the dock that ran parallel to the canal. She fl ew the Canadian ensign, a predominantly red fl ag with the Union Jack in one corner and the Great Seal of Canada toward the center. She was an animal transporter about halfway fi nished unloading hundreds of horses destined for the front and hundreds more sheep destined for the soldiers’ mess. The passage had to have been even worse for the animals than it had been for the passengers aboard the Duke of Monmouth because the quay was awash in loose dung.

Men with hand-pumped hoses were washing the treacle into the canal, but that did little to alleviate the cloying stench. All the horses Bell could see stood with their heads low, their tails motionless, and their mien listless. The sheep that had already been unloaded and fenced inside temporary corrals bleated miserably, their once-white coats stained down almost to the skin.

The cowboys who’d tended the animals all the way from Halifax, sleeping near their stalls and keeping them fed and watered despite the rough seas, were struggling to keep their charges together. Only a few had mounts well enough to ride, leaving just a handful of the ranchers to coax the seasick animals into a semblance of a line so they could be herded to a nearby railhead. From there they would be transported to farms around the south of England, where they would be acclimated and then trained to become warhorses.

Bell had read somewhere that the British were losing around three hundred horses per day on the front. It was early March. He doubted any of the animals on the pier would see the summer.

The Monmouth slid past the livestock transporter and came up

against its pier, the harbor pilot working the ship’s rudder and engine to ease the liner up against the dock with barely a kiss. Below, workers with scarves tied over their noses and mouths because of the smell prepared to unload the ship.

Bell assumed that whatever cargo and passengers she’d return with to North America would be loaded at her regular slot back in Liverpool. Providing for a nation that was fi elding millions of men in a foreign country to fight a war no one really wanted was an exercise in precision timing and industrial might on a scale never seen in all of human history.

One group of men on the pier caught Bell’s eye. A couple were obviously dockworkers, but two looked different. They wore plain clothes but had the look of cops, sharp- eyed and situationally aware. They stood around an open back lorry with a canvas cover protecting the driver and passenger compartment. The stevedores smoked cigarettes while the two police guards scanned the ship. They knew he was coming in as a second- class passenger and so ignored the people on the top deck already getting ready to depart the ship via a long switchback set of gangways.

The second- and third- class passengers returning to Europe after working in America wouldn’t disembark until the premier passengers had all cleared customs and were on their way to London or wherever they were headed. Just by interpreting their body language, the British police recognized the two Van Dorn men slouched against the Monmouth’s railing. While other passengers gawked at the sights of the harbor and the canal traffi c still moving past or stared in fascination at the chaotic unloading of the horses, Bell and Eddie Tobin watched the cops.

The older of the two cops pointed in Bell’s direction. In turn Bell pulled a slender fl ashlight that was no bigger than a cigar and used

the nonstandard AA batteries from his overcoat pocket and fl ashed the Morse code of his initials: Dot, dot. Dash, dot, dot, dot.

The policeman acknowledged the gesture. Bell swung his gaze toward the Duke of Monmouth ’s bow. The forward hatch had already been knocked open and an operator was standing by the mast derrick. Near him was the ship’s third officer, as previously arranged when the assignment had been discussed with the ship’s owner and captain. Bell’s cargo would be the fi rst off the ship and the police in charge to receive it would be well on their way before anyone else cleared customs with their luggage.

As the crane hook vanished into the hold, Eddie nudged Bell and pointed at something happening on the dock. “Hey, boss man, what is that thing?” he asked.

Bell wasn’t sure. It was a wheeled tower made of metal struts with a ramp that spiraled down from the top all the way to the ground. The floor and outer wall of the helical were made of individual rollers that would spin freely if something were to pass over them or bump against them in the case of the outer wall.

“If I’d have to guess,” Bell said as the odd tower was wheeled closer to the ship, “it’s some Rube Goldbergian contraption for unloading steamer trunks. A guy on the ship sets a trunk on top and with a little shove it coils down and around the ramp until it reaches the bottom and another stevedore is there ready to heave it onto a waiting truck. If you notice, the struts can be jacked up or down depending on how high up on the ship the trunk storage compartments are.”

“Damned clever.”

“Necessity is the mother of invention,” Bell said. “The Brits are facing a massive labor shortage with all their men off in the trenches, so they need to get creative.”

Dockworkers pushed the unloading ramp toward the ship, while the crate Bell and Eddie had been hired to protect rose from the forward hold. It looked like a standard packing crate, maybe with thicker-than-average wood, but unremarkable in all respects. Once the crate was high enough to clear the ship’s rail, the boom was swung outward enough for it to lower the package directly onto the waiting truck. The two cops stepped back as the stevedores craned their necks back and reached up with their arms to guide the load into position.

As soon as the crate landed on the truck’s open bed, a carefully set trap was sprung.

THE TWO STEVEDORES TURNED ON THE POLICE OFFICERS, swinging leather cudgels with lead- shot heads, while a third supposed dockworker raced to the scene and leapt onto the truck’s bed to slash the knots securing the crate to the crane. Bell gave credit to the operator on board the Duke of Monmouth. He was quick on the controls, but when he spooled back the iron hook, the ropes had just parted and the crate remained on the dockside in the bed of the AEC Y- type lorry. The bobbies were laid out on the dock, dark stains around their heads where the coshes had likely cracked bone.

Bell’s mission had ended the moment the crate landed in the back of the truck, but that didn’t end his personal commitment. He could no more let the crime unfold before him than he could stop the sun rising in the east.

The gangway to unload passengers was two decks up and half the ship away. Out of the question, so Bell took the alternate route

off the Duke of Monmouth. With a startled grunt from Eddie Tobin, whose shoulder he used to climb onto the rail, Bell moved down the thin wooden rail with the agility of a cat and twice the cunning. As the loading derrick hook swung back around the side of the ship, Bell put on a burst of speed to launch himself at it, not thinking about the thirty- foot drop to the unforgiving concrete below.

He was weightless for only a moment before his hands wrapped around the cold steel hook with a sure grip. Momentum swung the line even farther out, like a penduluming weight at the end of a string. He arced back toward the ship right above the unloading trunk tower. He let go just before he was above the contraption and his body arrowed downward like a dart. He hit where the ramp met the wall, a blow hard enough to knock the air from his lungs in a painful whoosh. But there was no time to fi nd his bearings. The rollers were as fi nely made as the insides of a Swiss watch and he was soon being flung around the coiling spiral, dropping and accelerating until he reached the bottom and was tossed from the device with all but his dignity.

He rolled once, twice. The third time slowed him enough to get to his feet. The truck carrying off the safe was just pulling off the Duke of Monmouth’s relatively calm dockage and into the chaotic scene near the Canadian livestock transporter. Because that was a freighter and not a passenger liner, customs was handled far differently. There were no customs halls or immigration lines. It was all handled quickly and with minimal fuss so that the horses weren’t kept waiting unnecessarily. That meant that once the thieves passed the ship, they had an open lane between two brick warehouses and out into the town with nothing to stop them.

Few workers had paid much attention to what had just happened

and were thus startled when Bell tumbled off the unloading ramp. No one tried to stop him as he took off running after the truck, his Browning pistol already in hand.

With so many horses being moved from the Canadian ship, not to mention the mounted riders trying to keep them in a loose formation, the truck couldn’t make much more than walking speed as it crossed the quay, evoking the occasional curse from a cowboy whose horse they spooked with a blare of the vehicle’s horn.

Bell wasn’t making much better headway himself. He could dodge and weave around the horses, but there were so many of them milling about that it was like running through a roan- colored maze. Plus he had to be on constant alert because some of the more agitated horses bucked their back legs in explosive kicks powerful enough to stave in a man’s rib cage.

He kept losing sight of the truck and fi nally climbed up on a twohorse wagon loaded with a tightly bound wheel of hay that easily weighed a couple of tons. The thieves were far closer to the exit than he’d expected. With a quick motion he pulled the razor- sharp knife he kept strapped around his ankle and slashed the rope holding the eight- foot- diameter- round hay bale into the bed of the wagon. A snap on the rein jerked the wagon enough for the hay to fall off the back. It hit the dock with a thud and rolled only a couple of feet before its ponderous weight stopped it dead.

Bell snapped the rein again and the two horses hitched on either side of the disselboom put their shoulders into the chase. Unlike the truck or even Bell on foot, the unfettered horses heeded their herd instinct, and while they didn’t follow the charging wagon, they got out of its way.

In moments, he found that he’d closed the distance, but saw that they were nearing the narrow alley between the warehouses that led

out of the dockland. Once through, the truck would speed away and there was nothing he could do to stop them.

Bell was determined not to let that happen. The moment he’d hurled himself off the Duke of Monmouth, his professional reputation, not to mention his own sense of right and wrong, was on the line.

He’d holstered his pistol when he’d leapt onto the hay cart, but checked again that the automatic was secure under his left arm. He cracked the reins again to keep the horses after their target and stepped down off the wagon’s driver’s seat and onto the yoke pole between the two charging draft horses. The thunder of their hooves grew deafening now that he was standing just eighteen inches above the cobbled pier on a round length of wood no wider than his hand’s span.

The horses sensed him in the unfamiliar spot and immediately started sweating, waxy bubbles like sea foam forming under their leather tack. Bell moved like a tightrope walker on a swaying pole, inching himself forward without physically touching the horses because he didn’t know how they’d react. If he slipped he’d land under their rear hooves and then get run over by the wagon. Death would be preferable to the paralyzing injuries such a fall would likely produce.

He kept moving forward. The horses had caught up to the truck as it navigated the narrow alley, a darkened passage with just a trace of sunlight reaching down to the roadway. The animals’ chests were barely a foot behind the lorry’s tailgate. Bell could plainly see the stolen trunk in the bed, and he noted that neither man was looking at the vehicle’s side mirrors. They had no idea he was onto them.

Bell reached the end of the disselboom. While he was shimmying out, he’d been able to maintain his balance, but once he stopped he

started swaying dangerously. He assumed the left- hand horse was the leader of the pair and so he momentarily steadied himself against the animal’s seesawing neck with a light touch.

The horse wasn’t the leader of the two. England drove on the opposite side of the road and so it was the horse in the right trace that kept the team working as one. Bell’s presence on the cart pole had been troubling enough, but once his hand touched the subordinate horse’s neck, its eyes rolled into its head so that only the whites showed, its tongue tried to snake around the bit, and it broke its gait. The lead horse tried to keep up the pace, but it was no use. His partner was in a full panic, and if not for the straps and yokes holding him in place, he would have bolted with every ounce of his considerable strength.

Bell realized his mistake the moment he’d made it, but the damage was done. The fleeting window of opportunity to leap from the wagon onto the truck was lost as the team slowed and the lorry pulled away.

He held on to both horses, cajoling them to slow. “Easy, boys. It’s okay,” he kept repeating. “No need to bother now.”

They emerged from the alley. The thieves were halfway across a mostly empty parking lot. In another thirty seconds they’d reach an unmanned gatehouse and turn onto the road leading away from the Runcorn docks. Bell stepped down off the pole and came around the front of the horses to pet their noses and calm them further.

A cowboy in a fleece-trimmed shearling coat and a Stetson rode up just then, pulling back on the reins hard enough for his mount to rear up for a moment. He dropped the reins across the horse’s back, a signal for the animal to freeze, and produced a braided leather whip, which he uncoiled so that its tip fell to the ground.

“You’re gonna lose a fair amount of flesh for what you just done,” he said in a low growl. “Move away from them horses.”

He just started to curl his wrist and raise the whip when Bell drew his 9 millimeter and aimed it dead on the cowboy’s beaky nose. “Drop the whip or I drop you.”

The cowboy had a big revolver hanging from his hip in a holster fitted with loops for extra bullets. Bell could see the gears turning behind the man’s eyes, calculating if he could toss the whip at Bell to foul his aim and draw his own weapon for a kill shot.

“I’m a private detective,” Bell said, still unsure if he’d have to shoot the man. “I was chasing thieves who just stole several million dollars in gold.”

Just then, a car entered the alley from the far end, its engine keening and its driver squeezing the horn’s bulb for everything it was worth. The fast-approaching vehicle was enough of a distraction to defuse the situation. Bell saw the tension run out of the cowboy’s shoulders and whip arm.

The car braked almost as hard as the cowboy’s horse moments earlier and the beautiful blonde from fi rst class leaned out the window and said to Bell, “Get in. We still have a chance.”

Bell gave the cowboy an apologetic look and leapt for the car’s running board. The mission was offi cially over and he was off the clock, as they say, and so he no longer had to pretend his wife hadn’t been on the same steamer over from New York as he and Ed Tobin.

Marion Bell eased her foot off the clutch, over-revved the engine a bit, but got them rolling without stalling it. Forced to shift with her left hand in the right- hand- drive Austin 40, Marion had trouble synching the gears, but eventually meshed them with brute force and some unladylike oaths. Bell wrestled open the passenger door and

got himself seated as the car began putting on some speed. The truck was too far ahead to see, but for now there was only one way out of the port, so Marion drove with confidence they were going to catch their quarry.

“Where’s Eddie and where did you get this car?” Bell asked, unsurprised that she’d come to his rescue.

“Eddie was still trying to fi nd a way up to fi rst class so he could disembark and come after you himself. Remember, you heels in the lower- class cabins don’t get off the ship until us toff s are on our way.”

Bell cocked a dubious eyebrow. “You’ve been in England two minutes and you’re already using their slang?”

She threw him a cheeky smile. “I do love it here, you know. The car belongs to a Lord something pompous- sounding who was returning to England after meetings with the War Department. He was at the captain’s table the fi rst night out and blathered incessantly. Then the weather turned so dreadful. I made it to the dining room a couple of nights, but His Lard Fatness remained in his cabin for the rest of the trip. Oh, and wasn’t that just a dreadful crossing?” Marion’s delivery was a rapid-fi re staccato that was music to Bell’s ears.

“It was,” he agreed. “The car?”

“Car? Yes, the car. Well, the Earl of Too Many Sandwiches was on the pier arguing with the porters about his luggage and his driver was just standing around. I saw you steal that wagon, so I figured I might as well steal something a bit more practical.”

Bell laughed. “You are a marvel.”

“And don’t you forget it.”

All around them were warehouses and small industrial concerns with tall chimneys belching black smoke into the already hazy air. There were countless trucks and horse- drawn wagons and men

shouting orders. A heavy booming sound came from a foundry as massive trip-hammers fl attened cold-rolled iron. While the thieves could have turned off onto any one of the side roads crisscrossing the commercial area closest to the docks, there was only one major artery out of the maze, and logic dictated that the men would want to put as much distance as possible from the scene of the crime.

The area gave way to some open land and a proper road heading inland. Traffic was light.

“There,” Bell shouted, pointing. Up ahead was an open-backed truck moving faster than the rest of the cars on the road, passing where it had barely any room to maneuver.

“Hah!” Marion whooped and tried to sink her foot through the floorboard. The four- cylinder engine responded like a thoroughbred and they quickly started passing the cars that the truck had just rushed by.

As they turned slightly north, back toward the canal and the Mersey River, an odd structure appeared out of the haze. It was a bridge of some sort, but unlike anything Bell had ever seen before. It consisted of two towers nearly two hundred feet tall with a thousand-foot-long steel latticework truss lancing across the river about halfway up. The massive weight of the steel girders was supported by wires like a conventional suspension bridge from the tops of the towers. The span was eighty or so feet above the water, giving clear passage for all but the largest ships. Bell couldn’t understand how anything could cross the bridge. There were no ramps up to the truss like those used to access the Brooklyn Bridge back in New York.

Then he noticed a platform big enough for several trucks as well as hundreds of passengers dangling from the truss on a cableway system like an aerial tram. The passenger area was glassed in like a

greenhouse, but was as ornate as a decorative birdcage. Above it was a glass- enclosed cupola for the operator. The entire structure had the delicacy and industrial grace of Paris’s Eiffel Tower.

The cable car hung just a dozen or so feet above the water, so its trips across had to be timed to avoid ships headed toward Manchester or heading west back to the Irish Sea.

“It’s a transporter bridge,” Bell said as he suddenly recognized the hybrid structure. “Never seen one before. Not as efficient as a suspension bridge, but a hell of a lot cheaper and easier to build.”

“Judging by how slow that platform is moving, if we can’t make the same trip across as the thieves, they’re as good as gone.” Addressing her own concern, Marion fl ashed past a lorry loaded with bails of barbed wire, doing nearly twice its speed.

“Easy,” Bell cautioned. “They don’t know they’re being followed yet and I don’t want to lose that advantage. There’s a couple of them and only one me.”

“You’ve got me,” Marion said with a defi ant lift of her chin.

“I do, but I only have one gun.”

“What about the derringer you always carry?”

“Dropped it between two running horses,” he admitted.

“Nicely done, Keystone.”

The thieves’ truck started across the bridge’s access pier. Marion’s deft driving had managed to get them only a couple of cars back. They would make the crossing together.

“Shouldn’t you arrest them now?” Marion asked.

“Too many people,” Bell said. A large crowd was gathered next to the road, where they waited their turn to cross the Mersey River on the large cableway platform. “If those guys are armed it could turn into a massacre. Better we confront them in a less- crowded spot.”

The transporter reached the loading ramp. A worker was ready

to open the safety barrier, while behind him at least fi fty people had left the sheltered passenger compartment and waited to rush off the platform. Most were workers from the industrial sprawl on the far side of the river and at least half were boys barely in their teens, while the others were older men nearing retirement. It was a stark reminder that the young men of England were shoulder- deep in muddy trenches across the breadth of France.

The platform came to a stop with a slight slam of metal on metal that caused a few of the passengers to sway. The barrier came down and the throng of people rushed from the transporter, eager to get to their next destination. Then two trucks trundled off the platform followed by a wagon being pulled by a lone pony.

The worker made a hand gesture and the next set of passengers stampeded onto the transport, rushing for the enclosed area to get out of a misting rain that was intensifying. Bell could see ahead that the thieves were ordered onto the platform under the guidance of a worker, who wanted them to park at a specifi c set of marks.

Next aboard were two Austin sedans a few years older than the one Marion had lent herself. Then came a wagon pulled by a single horse, and fi nally it was their turn. Mindful that she was driving an unfamiliar car, Marion was easy on the clutch, inching the car onto the platform as if she had all the time in the world.

Without warning, the transporter lurched away from the loading ramp. It took just a second for the platform to pull itself from under their car’s front wheels. The bridge worker who directed traffic had a horrified look on his face at the disaster unfolding before his eyes. Marion didn’t have time to react. The transport platform slid out from under their Austin and the car’s nose fell so that the chassis just behind the engine hit the loading ramp and the vehicle began to teeter

over the edge, balanced as if on a knife’s edge. The engine stalled and the dying vibration set the car rocking in ever larger arcs.

The sudden drop had slammed Marion into the steering wheel, and had Bell not braced himself at the last instant, he would have likely been launched through the windshield. Their view out the windscreen was of the green waves of the Mersey at ebb tide rushing past at a ferocious speed.

The car continued to rock like a child’s teeter-totter. The transport platform was already a few yards away, the worker still standing in shocked awe with a couple of passengers at his shoulder staring in horror at what was about to happen.

Keeping his left arm braced against the dash, Bell used his right hand to grab the back of Marion’s coat and pull her back so she was pressed into her seat.

“Don’t move. Don’t even breathe hard,” he cautioned in a whisper. “We’re one toot away from toppling into the river.”

Bell took a second to study the operator’s perch atop the mobile platform. As he’d guessed, there were two men up there now and one looked like he had a knife pointed at the uniformed crewman. The thieves had spotted their tail and forced the operator to try and kill them by pulling away when they were only half aboard.

He cursed, but then set himself the task of saving their lives.

Like a momma cat moving her kittens, Bell kept his right hand clamped onto the scruff of Marion’s coat and began lifting her up and over the back of her seat. Had they been in America, and seated on the right, he wouldn’t have had the strength, but here he could unleash the full power of his dominant arm. He had little leverage, other than what he could generate by tightening the bands of muscles across his lean belly.

A groan escaped his lips as her backside formed a supple speed

bump over the headrest. Finally he managed to deposit her in the back seat. The Austin teetered for a few seconds more and then its rear tires kissed the road once again, though only with a few pounds of pressure. People suddenly swarmed the car, pressing against its back bumper to keep it from going over the edge. They were the workers who’d just gotten off the transporter and must have sensed something was wrong and returned.

The Austin was now fi rmly planted on the deck. The rear doors were opened, and Marion was pulled to safety. The crowd roared their approval when she emerged from the back seat and Bell was encouraged to climb over into the passenger seats after her.

“Hold it tight,” Bell said as he climbed from the car. “It still might—”

No one listened. As soon as he was clear, the men and boys weighing down the back bumper let go as one. The car’s rear lifted a few inches, fell back, bounced and lifted again, until it passed a point of no return. The Austin tumbled off the access ramp. It was a fi fteen-foot fall into the swiftly flowing river, and by the time Bell reached the edge of the ramp to look down, the sedan was already half sunk and a good twenty yards downstream.

“Think that’ll buff out?” Marion quipped.

KNOWING MARION WAS NONE THE WORSE FOR THEIR CLOSE call if she could crack a joke, Bell bulled his way through the celebrating throng and raced for the bridge support tower. There was a set of spiral stairs that coiled their way up to the overhead truss within the spindly structure. It was closed off by a padlocked iron gate. Bell had his gun in hand when he reached the gate.

It proved to be a stubborn lock that took two bullets before it fell away. Bell barreled into the gate, crashing it back against its stops before he took the curving steps two at a time. It was an eight- story climb to the level of the suspended box truss that spanned the river and Bell was breathing heavily, but by no means winded. The slowmoving transporter platform was about halfway across, with the fi fty- foot- long scaff old dangling just a dozen or so feet above the river.

From this height, it looked smaller than Bell would have thought.

Apart from the great girders that made up the enormous truss, there were two thick cables that pulled the trolley back and forth across the Mersey and a narrow path for maintenance workers to safely traverse the span. Bell took off at a run, mindful that the steel was slick with rainwater and his shoes more befi tting of an ocean liner crossing than a high-wire act.

Because of the way the structure was held together, with innumerable cross braces, Bell couldn’t see what was happening on the platform below. He imagined the abrupt departure had rattled the passengers, but he didn’t know how they would react. He hoped that they stayed together in the enclosed lounge because he was determined not to let the transporter dock at the far side.

He ran at almost twice the speed of the moving platform, but he’d lost so much time in the Austin and then climbing the tower that he had only a few seconds before the thieves would be on the opposite bank. He reached the slowly trundling trolley and its dozens of cables that suspended the platform above the water. There was no easy access because there was no need for anyone to attempt what he was about to do.

Bell double- checked that the Browning pistol was strapped in his shoulder holster as he stripped off his suit jacket. No one down below had spotted him high above the platform, and for that he was grateful. The cables supporting the transporter were as thick around as his wrist and made of countless braided wires. Though the bridge was only a decade old, rust had turned the outer wires scaly, with hundreds of burrs sharp enough to peel the skin from his hands. Bending low to wrap his jacket around the cable, Bell tightened his grip as hard as he could and let himself fall, controlling his descent by yanking at the sleeves of his jacket as though it were a garrote. He plummeted the seventy feet in just a couple of seconds, but slow

enough that when he hit the deck and shoulder-rolled away from the cable, he could immediately bounce up onto his feet.

His sudden appearance made the few people standing outside gasp and point in surprise. The thief high above in the operator’s cab saw him land as well. He shouted something that was muffled by the glass and he redoubled his threats of violence to the bridge worker. There were two more thieves. One was in the cab of the truck, while the other stood in the back of the lorry guarding their prize.

Bell had always known that guns were hard to come by in England even for seasoned criminals. That was why none had been used in the hijacking back on the dock and why the transporter operator had a knife to his throat rather than a gun to his head. Bell knew he had the advantage when he pulled the 9-millimeter automatic from his shoulder rig and pointed it at the truck.

“Shut off the engine and step down with your hands up,” he shouted in his most authoritative voice. It was the type of command he rarely had to give twice.

It didn’t have the desired effect.

With a swirl of his waterproof mackintosh, the thief in the back of the truck pulled out a sawed- off shotgun from under his coat. Bell wanted to dive to his right, behind a piece of structural steel that gave the platform rigidity, but it would put the greenhouse-like passenger gondola between him and the shooter. Instead he dove left, fi nding scant cover behind a high- sprung wagon fi lled with winter potatoes.

He edged around to the side of the wooden wagon, aware that if the gunman jumped down from his truck he could send a spray of buckshot under the carriage that would tear his legs to shreds.

A female passenger, already on edge because of the odd departure from the canal side of the river, noticed the shotgun and let out a

bloodcurdling scream that sent an electric jolt of panic through the rest of the riders. People pushed and shoved in a vague attempt to get away, even though they were all trapped on the platform, which was still several yards from reaching the far bank. Glass shattered as bodies were shoved against the gondola’s delicate walls, and soon blood began to flow as people were sliced open by the shards.

Bell understood that the panic would soon morph into a fullblown frenzy, the kind of melee where people were killed for being in the way of someone bigger and stronger than themselves. With little regard for his own safety, he stepped up onto the hub of one of the wagon’s wheels. The gunman in the truck had a rough sense of where he was, but needed a second to swing the shotgun a couple of degrees for it to center on his target.

For his part, Bell knew exactly where the shooter was standing and had a bead on him as soon as he emerged over the cart’s high side. Pop, pop. Two to the chest so tightly grouped it looked like a single hole. The impact drove the man against the truck’s bed and he pinwheeled out of the back and over the side of the platform. His corpse hit the water hard enough to sink below the surface and wouldn’t pop up again until it was a half mile downriver.

Bell whirled to draw a bead on the knife-wielding thief up in the control cupola, but with the ironwork frames and all the glass windows, it was impossible to take a safe shot that wouldn’t hit the operator.

Just then came the painful crack of a Webley revolver fi ring in Bell’s direction. The thieves might have acquired fi rearms, but they’d had little practice with them. The shot whizzed by several feet wide and overhead. The shooter had been in the cab. He’d taken the shot while standing on the truck’s running board and the recoil had lifted his arm, and the heavy top-break revolver, high into the air. So ill-

trained in armed combat, the man hadn’t bothered to duck back behind the truck’s cab.

Bell fi red just as the moving platform hit the loading ramp on the far side of the river. The impact threw his aim off and so the round missed. Now the driver ducked back into the cab. The engine had been left running and he wasn’t about to wait for his partner up in the cupola to make his way down to the main deck. He gunned the motor as he jammed it into gear.

Knowing he had only one chance, Bell vaulted up to the wagon’s seat. The horses must have been used to gunfi re because neither of them paused at nibbling from the canvas feed bags the wagoner had tied around their noses. The truck was just starting to move. Bell put a round through the truck’s rear window and knew he’d hit the driver when the windshield was suddenly a red dripping curtain. The truck veered slightly, hit a guardrail, and ground to a stop.

Bell swiveled his aim up to the control cupola once again. This time he didn’t need to worry about hitting anyone. The third thief had dropped his knife and stood with his hands up. Apparently he believed a few years in prison was better than a lifetime in a casket.

Despite the efforts of the crewman tasked with securing the platform to the ramp, passengers were rushing from the scene en masse. Those waiting on the ramp hadn’t been close enough to see exactly what had happened and waited like a flock of nervous sheep.

The wagon’s owner, a raw-boned farmer with just a monk’s tonsure of white hair, approached, hat in hand. He was clearly more concerned with his animals’ welfare than his own safety.

“I’m a private detective,” Bell stated, making fl icking motions with his Browning’s barrel that told the thief to exit the cupola and join him on the main deck. “Those men stole cargo off a ship unloading a ways down the road.”

“American?” the man asked.

“Yes.”

“Never met one before.” He paused, considering something, and then asked, “Why aren’t you helping us with this war?”

To Bell it sounded more like an accusation than a question. “For the same reason we didn’t get involved the last time the French and Germans had at each other. This is a European problem.”

The thief approached, his hands still held aloft. Bell asked the farmer if he had any rope, which the man found after rummaging under the wagon’s bench seat. Bell had the thief sit and tied his hands to one of the cable anchors.

“You know this war’s different.”

Bell did know, but said nothing. The two men regarded each other for a few seconds and then the farmer turned away to lead his team and their load of potatoes off the transporter.

It took twenty minutes for some senior police detectives to arrive and another two hours of interrogations before they were satisfi ed they had all the details sorted out. The cops and government agents who’d been jumped at the docks had helped smooth the proceedings and had taken possession of the truck for its eventual transport down to London. By then the shotgun-wielding thief had been fi shed out of the river and the lone survivor had been carted off to a jail cell in Liverpool.

Marion fi nally joined him on the transporter’s fi rst run after its continued operation had been authorized by the police. The few broken glass panes had been replaced with bits of canvas and the shards swept over the side. Buckets of water had sluiced any blood from lacerated passengers into the river.

She pressed herself hard against his body and kissed him long enough for some of the men milling about to turn away in embar-

rassment. “It’s a good thing I don’t watch you take foolish chances very often. My heart was pounding the whole time.”

“Mine, too,” he admitted. “And just so you know, that wasn’t a foolish chance, but rather a calculated risk.”

“Pish.” She dismissed him with a wave and a flash of her Caribbean-blue eyes.

“We’ve missed our train to London, I’m afraid,” he told her.

“No matter. We can spend the night here and head down tomorrow.” A sudden thought struck her and her excitement was infectious. “We can get a room at the Adelphi. We always sail out of Southampton, so we’ve never stayed here in Liverpool. Friends have said the Adelphi is lovely, and everyone is absolutely mad for their turtle soup.”

Bell considered the idea for a moment. “Turtle soup it is. I can telegraph the London office from the hotel and tell them we’ve been delayed a day, as well as notify the Savoy so we don’t lose our suite. The police offered me a ride back to the docks now that we’re done here and I’m sure the steamship line is holding our baggage.”

She threaded an arm through his and said with mock innocence, “If they don’t, I won’t have a single thing to wear to bed tonight.”

THE MEETING WAS HELD IN THE WHITE HOUSE, BUT PRESIDENT Wilson didn’t attend. He let one of his chief advisers, Colonel Edward House, handle the discussion. House was a Texan who’d made his money in railroads and banking and had transplanted to New York in 1911, where he soon became a close confidant of then New Jersey governor Woodrow Wilson. He was of average build, tending toward leanness with a tall forehead, prominent white mustache, and jug-handled ears.

He sat at the head of a conference table while the secretary of war, Newton Baker, sat at the other end. Between them sat the secretary of the Navy as well as all three men’s chief assistants. For Josephus Daniels, the Navy secretary, this was a young, patrician- looking New Yorker named Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He had a long face, stylish wire-framed glasses, and a quick and inquisitive mind.

There was some fi nal rustling of papers and lighting of cigarettes before the meeting got underway.