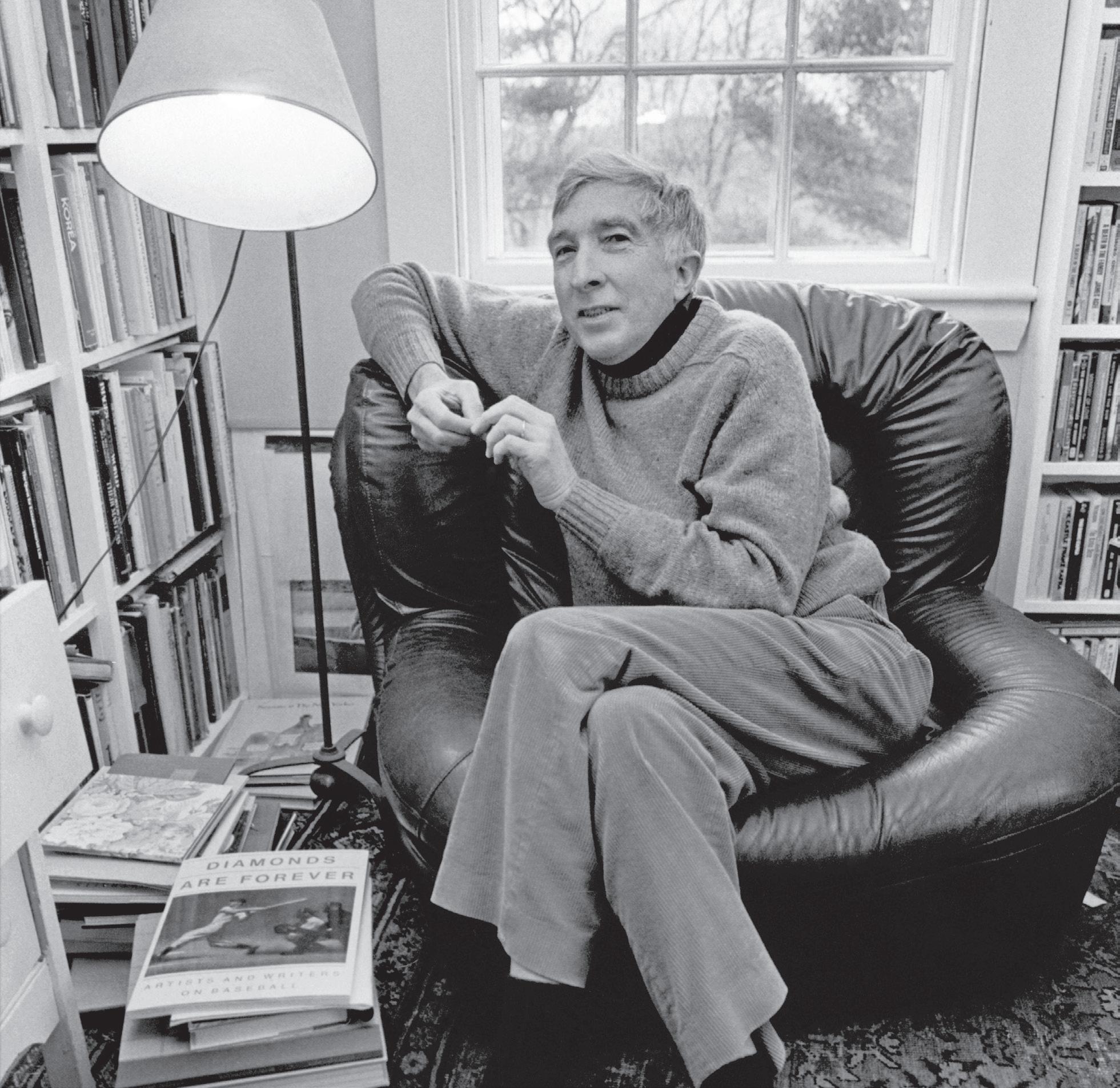

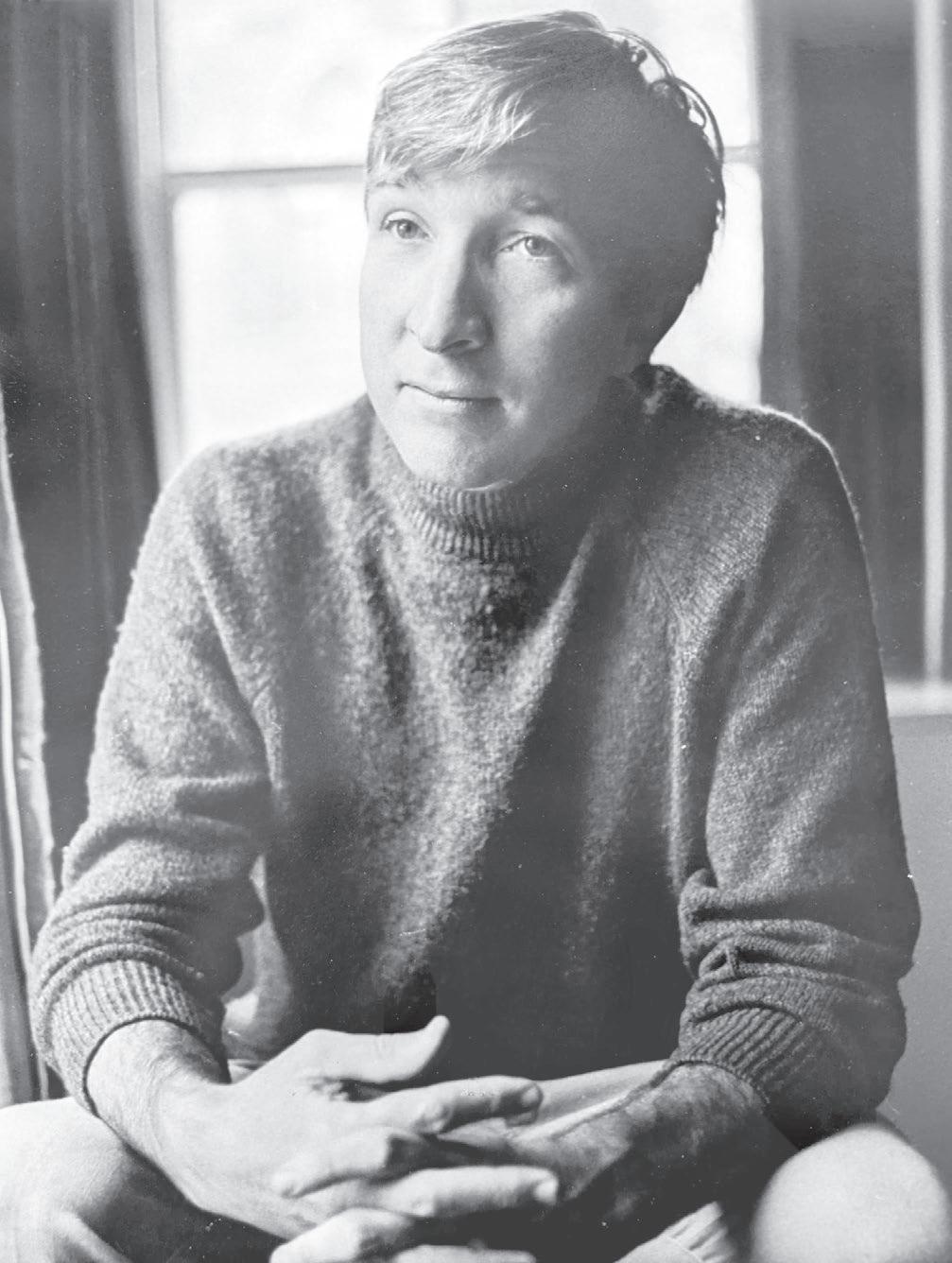

A Life in Letters John Updike

EDITED BY JAMES SCHIFF

HAMISH

HAMILTO N an imprint of

HAMISH HAMILTON

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Hamish Hamilton is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published in the United States of America as Selected Letters of John Updike by Alfred A. Knopf 2025

First published in Great Britain as A Life in Letters by Hamish Hamilton 2025 001

Copyright © John H. Updike Literary Trust, 2025 Introduction © James Schiff, 2025

The moral right of the copyright holders has been asserted Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978–0–241–70758–6

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

Introduction vii

Note on the Text xxiii A LIFE IN LETTERS 1

Chronology 823

Acknowledgments 835

Index 839

Introduction

BORN IN 1932, John Updike came of age when letter writing—not texting, email, Twitter, or telephone—was the primary means of communication. As an ambitious, artistic adolescent eager to publish his poems and cartoons, Updike, who was living in a remote farmhouse in Plowville, Pennsylvania, began sending submissions to magazines in 1945, when he was just thirteen. Around the same time, he was typing precocious, adulatory letters to cartoonists he revered, such as Milton Caniff, Harold Gray, and Saul Steinberg. “Your draughtsmanship is beyond reproach,” the fifteen-year-old Updike tells Gray, creator of Little Orphan Annie, before pivoting to his request: “All this well-deserved praise is leading up to something, of course, and the catch is a rather big favor I want you to do for me. I need a picture to alleviate the blankness of one of my bedroom walls.” No doubt flattered, the artists often obliged by sending a drawing or cartoon. And so, through these youthful fan letters and magazine submissions, Updike began his lifelong effort to connect himself and his artistic aspirations to the distant, romantic realm of print.

After spending his first eighteen years in Pennsylvania’s Berks County (thirteen years in the town of Shillington, followed by five on a family farm in rural Plowville), Updike departed, in 1950, for Harvard, to which he had won a scholarship. At the time, long-distance telephone calls were extravagantly expensive. The only way to communicate with family back in Plowville, who craved his news, was by post. During his four years in Cambridge, Updike sent his parents and maternal grandparents more than 150 letters, most of them witty, eloquent, and substantial. By the time the last of those four adults died (his mother, in 1989), he had written her approximately two thousand letters, notes, and postcards. A similar compulsion to put his thoughts to paper guided his life as a freelance writer. When, in 1954, Updike began publishing poems and short stories in The New Yorker, then

books with Alfred A. Knopf in 1959, business was conducted largely through letters, and over the next fifty years, he would compose thousands of them to editors and staff at both of those institutions. Thousands more went to literary friends and colleagues (John Barth, Muriel Spark, Joyce Carol Oates, Philip Roth, Ian McEwan, Edward Hoagland, and others); readers, fans, and aspiring writers; booksellers, collectors, and bibliographers; academics, critics, journalists, and students. Many of these people had written to him first and, like the thirteen-year-old Updike, were asking for something: an autograph or note, an interview, an essay, a public appearance, advice, assistance with their manuscript, a few paragraphs on Strindberg, Karl Barth, or Tiger Woods. One stranger offered to babysit Updike’s children and proofread his novels, another invited him to play basketball in East Boston, and yet another wanted him to judge the Miss USA Pageant. While Updike said yes many times, perhaps more than he should have, he more frequently said no, though usually with a kind and amusing note. And so, over the years, those letters, notes, and postcards accumulated.

The typewriter was Updike’s primary tool for correspondence—he even typed postcards—and occasionally he would comment in a letter on the feel of the keys or condition of the ribbon. With the advent of word processors, Updike purchased, in 1983, a Wang, which he used for his fiction, book reviews, and eventually his correspondence. A series of personal computers followed, together with printers and fax machines, but Updike resisted most other new technology. Unlike many of his peers, he never used email or owned a cell phone. As the planet, before and after the millennium, transitioned to cell phones, email, and texting, Updike remained committed, until his death in 2009, to both the traditional letter form and the practice of typing, whether on a computer keyboard or typewriter.

While being born in the 1930s has much to do with why Updike became a letter writer, one wonders what led him to be so prolific, authoring more than sixty books, nearly two thousand short stories, poems, essays, and reviews, and thousands of letters, postcards, and notes.* Such vast production

* Recognizing that readers may wish for a count of the number of letters Updike composed, I nevertheless feel incapable of producing a final tally, except in highly speculative terms. In addition to the thousands of letters Updike wrote to family, friends, and readers, each of his nearly two thousand published pieces generated multiple notes or letters, some as short as a sentence or two, others several pages. Occasionally, these communications are written on Post-it notes or newspaper clippings. Should they count as letters? The same question applies to the thousands of postcards Updike composed. Though some are brief and unexceptional, others are substantive. Further, while archives have preserved many of the most important Updike letters, thousands more are likely sitting in attics, basements, or drawers; others, no doubt, have been lost or destroyed. This is of course true of the correspondence of all writers, yet given his prolificacy, the number of lost or discarded Updike letters is probably quite large. If pushed, I would speculate that Updike wrote more than twenty-five thousand letters, postcards, and notes during his lifetime, though the number could be substantially higher.

suggests more than simple industriousness. For whatever reasons—lifelong graphophilia, his family’s limited means, close witness of his mother’s literary ambitions and father’s personal sacrifices, a desire both to see his name and work in print and to use art “as a method of riding a thin pencil line out of Shillington”—Updike needed to write the way the rest of us need to breathe or eat. Eventually, over six decades, he would express himself in written form as copiously and as elegantly as any American writer before him. This fullness of expression is evident not only in the magnitude of his outpouring but in his possession of a range of almost preternatural gifts and rhetorical skills, which allowed him to work successfully in many genres and to address, as if effortlessly, any topic. His letters display the intellectual finesse, wit, and eloquence found in his fiction and essays, and so his correspondence figures not as an adjunct to but rather an integral part of his astonishing literary output. Filled with comic observations, opinions, and news, his letters collectively chronicle, over more than half a century, his daily existence.

It’s hardly a surprise that Updike excelled at a genre which required, on occasion, just a few sentences. Even his harshest critics were quick to grant his stature as a major stylist, and so his letters, like his other writing, are striking for their verbal precision, intelligence, sharp eye, and humor. Even when conducting routine business, Updike’s letters were seldom boring or perfunctory. His intent seemingly was to provide pleasure, for both writer and reader, even when complaining about the recipient’s request. Humor was his default mode, through which he could delight, yet maintain distance. There is little tragedy, trauma, or pain in these letters—Updike had a good, accomplished, and satisfying life. However, there is drama, along with conflict and problems. But mostly there is watchfulness. The letters provide a lifelong record of someone who absorbed the world around him with a high degree of intelligence and alertness.

ANY ATTEMPT TO understand Updike as a writer should begin with his mother. An extraordinarily bright farm girl from Plowville, Linda Grace Hoyer skipped multiple grades, graduated from Ursinus College at nineteen, earned a master’s degree in English from Cornell in 1925 (the same year she married), and devoted much of her life to writing fiction. As Updike explained to me many years ago: “I can remember a moment in the front room in the house in Shillington . . . when I was sick in bed and had a lot to say to my mother, and she finally indicated—she was at her desk trying to write—that she wanted me to be quiet. I was an only child, and much indulged, and I’d never before been asked to be quiet, so I realized this was a very momentous activity she was engaged in.” Sitting in the front bedroom,

his mother typed her stories and sent them to popular magazines such as Collier’s, The Saturday Evening Post, Liberty, Cosmopolitan, and Redbook. As Updike recalled, “I was invited as a child, as a sympathetic child, to read these things, so at about the age of eight I became one of the youngest unpaid editors in the country.” Unfortunately, the brown envelopes containing her stories were always returned, though occasionally with a note of encouragement on the rejection slip. Thus, at an early age, Updike witnessed firsthand the life of an aspiring writer, who, he recalled, “was frustratingly close to being publishable. And I could feel, even as a child, the closeness, and I didn’t have it in me to boost her over that perilous edge into print.”

Updike’s mother prepared him for his career, passing down “her love of words, her love of the right word,” and a sense of “the devotion it takes and the solitude of the craft.” She also arranged for his art lessons and took him to the Reading Public Library, where he encountered “these towering walls of books,” which made a deep impression: “being one of those authors seemed to me like being an angel in heaven.” In addition, she was the driving force behind their unsettling move, when Updike was thirteen, from the town of Shillington to her farmhouse birthplace in the rural isolation of Plowville. Forced to leave his peers just before embarking on a high school experience that would have taken place almost literally in his backyard, Updike suddenly found himself displaced, living ten miles away on eighty acres in a tiny sandstone farmhouse with his parents and maternal grandparents. So small and tight was their living arrangement that his bedroom was not an actual room but rather the upstairs hallway, located between the grownups’ bedrooms—hardly an ideal situation for an adolescent. Yet in Plowville Updike had ample time to read, write, observe nature, and converse with four articulate adults, each of whom poured their love and hopes into him.

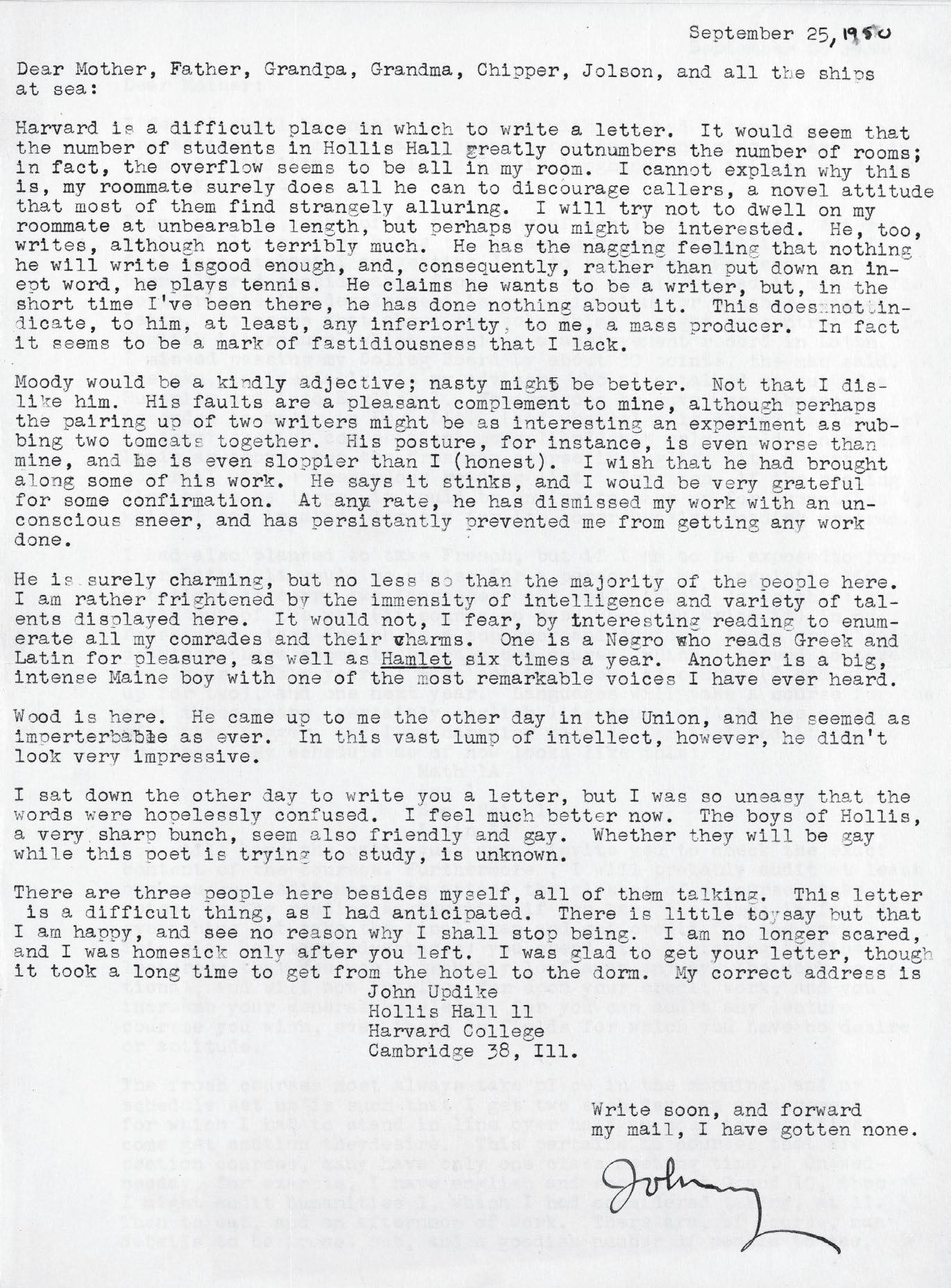

It’s hard to overstate the importance of his family during those early years, and it didn’t stop when he enrolled at Harvard. Within a few days after his arrival at Hollis Hall, his freshman dormitory, Updike became aware, if he hadn’t already anticipated it, that his primary correspondent, his verbal volleying partner, would be his mother. During a busy first year in which he studied hard, submitted writing and artwork to The Harvard Lampoon, and sought to assimilate into an unfamiliar and privileged environment, Updike composed fifty-four substantive letters to his family. Commonly addressed “Dear Plowvillians,” these letters were read not only by the four residents of the sandstone farmhouse but also by neighbors, friends, and relatives. They became a source of entertainment and were often reread; as his mother revealed, “We all read your letters six, or is it sixty, times.” Further, the letters were not the crabbed, laconic, dashed-off notes often composed by college students of that era to ask for money. Filled with news and observations,

considerable humor and wit, occasional anxiety, and much thoughtfulness and love, they are among the finest letters Updike wrote. What becomes apparent in Updike’s letters home is not only his mother’s influence but also her need to converse with her son. While his letters were addressed more broadly to his parents and grandparents, his mother was the one who wrote back; during that same freshman year, she sent him ninetyeight letters. Both mother and son kept a loose tally of their exchanges those first couple of years. When Updike fell behind, during the fall semester of his sophomore year, his mother, in a letter of October 25, 1951, comments, “I am drawn into a whirlpool of doubts concerning our correspondence . . . my pride will eventually prevent my writing three letters to your one.” Expressing curiosity about “the doings at the Salamanca of the twentieth century”— a suggestion that Harvard resembled the Spanish city that was once a leading cultural center of Europe—she writes: “all your social adjustments become very interesting to us who have not been as successful in these delicate matters as we would have liked.” Though sharp and intelligent, Linda felt herself less adept at certain forms of social interaction than her son or her husband. His mother goes on to list her recent adventures in Plowville: trying to run a neighbor off their farm, discovering that after a lifetime of high blood pressure she now has low blood pressure, and peering through a nearby open stable door at what appeared to be “wall-size tapestries.” She concludes with a series of questions: “Shall I file all of these strange and wonderful experiences away for some future use? The heart asks what use? What future? Wouldn’t it be better to spend them now, hoping that the smile they have brought will somehow be carried through the mails to another? Answer me, John.” His reply, dated three days later, is a three-page, single-spaced letter, both humorous and defensive, in which he questions her tabulations on the imbalance of their correspondence and laments how uninteresting his life currently is, posing as “a letter writer . . . Who Has Nothing to Say.” He also mentions his mother’s writing instructor (in 1949, Linda began a correspondence course, “Fundamentals of Fiction,” with Mr. Thomas H. Uzzell, a writer and former fiction editor), who claimed that “an author should strive for an emotional effect,” which Updike then declares his mother achieves in her letters, while “mine, it seems, bring about consternation.”

What these early letters reveal is his mother’s desire, despite several hundred miles between them, to sustain their conversation, along with their mutual interest in chronicling daily activities. Unlike letters from the battlefield or romantic correspondence between distant lovers, these familial exchanges revel in the mundane. Linda offers descriptions of the farm’s inhabitants, both human and animal; provides anecdotes about selling hay bales and planting strawberries; delivers updates on her writing struggles and

Updike’s high school girlfriend; and gives her son advice about his classes and health. In turn, Updike discusses, with characteristic self-deprecation, the challenges of his courses and professors, the behavior of his roommate and friends, and his success with placing writing and drawings in the Lampoon. Though his letters are by no means confessional or deeply emotional, they are remarkably mature and perceptive for a college student.

The Harvard letters also mark Updike’s rapid rise as both a writer and a socially adept adult, two things with which his mother struggled. The farmboy from Plowville, living on a tight budget, quickly acclimated to a cultured, elite realm. Though it was not necessarily a world Updike loved, he thrived at Harvard: making friends, finding a girlfriend, placing an extraordinary amount of his work in the Lampoon, and receiving feedback on his writing from well-known, knowledgeable professors, which Linda was eager to hear. While he was more talented and possessed better working habits, both mother and son were drawn to similar material, the domestic mundane, and there was clearly reciprocal influence. After reading one of her son’s pieces in the Lampoon in 1954, Linda wrote to say she was “flattered that you stooped to steal two of my favorite images”; Updike replied, “Mother, let my theft of the square bowl of sunshine in no way impede your continued use of that excellent image. And as to the people who dig their heels into things—I was sure that was all my idea.” When Linda, in 1960, sold her first story to The New Yorker, Updike’s editor, William Maxwell, told him, “It is so interesting to see the same quality of mind running through both of you,” which led Updike, in a congratulatory letter to his mother, to write, “I take [Maxwell’s comment] to mean that for the last six years now I have been freely pillaging my mother’s imagination and memories to make fictions, a theft I feel guilty about now that the original has found her voice.”

While Updike’s mother was his most frequent correspondent during those first semesters at Harvard, his life changes dramatically during his sophomore year when, in a medieval art class, he meets Mary Pennington, a bright and pretty Radcliffe woman two years his senior. In his courtship letters to Mary—written mostly over the ensuing summer, when he worked as a copy boy at the Reading Eagle—Updike’s voice finds a new register, becoming more unleashed and intimate as he confesses his love and shortcomings, all the while plotting their future together. These letters are bursting with creative energy. One takes the form of a playlet, depicting a lovelorn office boy lamenting, to a talking pencil and telephone, the absence of Miss Mary E. Pennington; another is a full-page cartoon of his slumped body with comic descriptions of various body parts above the caption “picture of a young man as seen by the parents of a young lady.” These letters to Mary

reveal how adept he could be at romancing a woman, and the speed of their courtship is testament to his skill: they would marry after his junior year.

Updike goes on to graduate among the top ten students in his class and wins a fellowship to study at the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art in Oxford, England. A month later, he places his first poem in The New Yorker, followed a few weeks later by a short story. Over the next fifty-five years, he will publish more than 750 short stories, poems, articles, and reviews in the magazine. While some may view his success as having come easily, a consequence of genius over sweat, that is not altogether accurate. Recall that Updike had been submitting creative material since he was thirteen, and claims to have received hundreds of rejections before that first major acceptance. Further, while many of his subsequent submissions are accepted, quite a few are not, leading him, in a 1954 letter to his first New Yorker editor, Katharine White, to explain his recent failures through this analogy about the creative process: “I once saw a movie in which a chimpanzee, let loose in a laboratory, proceeded to mix, by accident, with his elbows, some sort of highly potent elixir. I know now how he felt when they wanted him to stir up a second batch.” In these early New Yorker letters, Updike is respectful and modest with his editors, yet simultaneously firm and confident about how his writing should appear in print.

After their year in England, Updike and Mary, with their first daughter, Elizabeth, return to the States, where he takes a job at The New Yorker, writing “Talk of the Town” pieces. Though it had long been his dream to work at the magazine and live in the city, he soon discovers Manhattan is not the place to nurture his talent, and as he and Mary have more children, additional living space is required. So the Updikes, less than two years into their New York adventure, move to Ipswich, Massachusetts, a small town north of Boston where they spent their honeymoon. There they will remain together for nearly two decades. (With the exception of a year in London with family, and eighteen months solo in Boston, Updike will spend the rest of his life in small North Shore towns.) While his personal and professional life would continue to evolve, at this early point in his career the major strands of his letter writing were already established: weekly missives home to Plowville; daily professional letters and notes (concerning submissions, proofs, edits, and queries) to editors and staff at The New Yorker and Knopf; and occasional bursts of romantic expression, similar to the letters he had written to Mary during their courtship. Within a few years, as his reputation and fame spread, a fourth strand would emerge: responses to those requesting either his time, presence, opinion, or a piece of writing. Over time, the recipients of these four established strands would change and expand: letters home to

Plowville would eventually be replaced by letters to children and grandchildren; professional communications with The New Yorker and Knopf would be augmented by exchanges with other magazines as well as fellow writers and critics; and romantic letters to his first wife would be succeeded by those to lovers, including his second wife, Martha.

In Updike’s early professional correspondence, several things become apparent—first and foremost, his ability to write quickly. During a visit to the New Yorker offices on May 21, 1964, Updike leaves a note for the editor William Shawn that reads, “Being here for an hour this morning, I thought of coming to see you, but figured it would be more to our purpose if I spent the time writing a ‘Comment,’ which is attached.”* When Harper & Brothers rejects “Home,” the six-hundred-page novel manuscript he completed in 1957, Updike produces a second, briefer novel, The Poorhouse Fair, in just a few months—and accomplishes this while placing dozens of items in The New Yorker. On a five-week family vacation in Anguilla in January 1960, he not only spends time on the beach with his young children but also reads books, writes letters, and composes four New Yorker stories, including “Pigeon Feathers.” The speed at which Updike could generate polished writing is remarkable. One also sees in his early correspondence with book editors a painstaking attention to detail regarding his published work (from punctuation to typos), along with his involvement in every aspect of the production of the physical book: jacket design, flap copy, font and point size, headers, margin, and topstain.

The central drama that emerges in his early professional letters pertains to potential charges of both libel and obscenity. After Updike’s first New Yorker story, “Friends from Philadelphia,” appeared on October 30, 1954, a man from his hometown wrote to say that “your father told me that old man Venne was the ‘Father’ in your story.” In a subsequent letter to Plowville, Updike urged his father not to “spread around these identifications,” going on to assert that the story “is not strictly true. A person in a story is never really a real person, and Mr. Venne never said any of the things I make him say, though he did let me drive his new Buick.” The threat of libel becomes more imminent upon the publication of “Snowing in Greenwich Village,” Updike’s first story about Joan and Richard Maple, which appeared in the New Yorker of January 21, 1956, and for which he borrowed the character and anecdotes of a family friend, Gulielma “Gulie” White, who visited the Updikes in their Greenwich Village apartment in December 1955. The story was published quickly, only nineteen days after it was submitted, which

* A “Comment” was the topical lead piece for the magazine’s “Talk of the Town” section. This particular submission, in which Updike describes returning to New York City and witnessing its “palpable, audible atmosphere of love,” opened the May 30, 1964, issue.

means the interval between Gulie’s actual visit, which inspired the story, and its appearance in The New Yorker was no more than a month. In a letter to Plowville of January 22, 1956, Updike wrote: “Gulie called up from her bathtub audibly shaken; all she could say was, ‘It’s spooky’—spooky, that is, to read a NYer story in which the main character emerges as you.” As Updike explained in another letter to Plowville, dated three weeks later:

Max Krook, Gulie White’s off-and-on physicist boyfriend, berated me more or less steadily for writing “Snowing in Greenwich Village” . . . The incidental people in the story have been teasing Gulie . . . Barbara, the girl who lived with the boy, came back from a visit, picked up an old New Yorker, and called Gulie, bawling her out for gossiping about her.

In an earlier letter to Plowville, Updike wrote: “everything in the Greenwich Village story (except the general import) was true. So a lot of the details about peripheral characters . . . had to [be] changed—slightly, but this was one of those stories in which the value seems to lie in the literal truth of what is described, and our changes seemed, in comparison with the fact, either dull or fanciful.” The possibility of libel would recur with his novel Couples (1968), to the extent that he had to resituate the novel from Boston’s North to South Shore as well as change various details about the geography and his characters. What is most telling, though, is the degree to which he mined his own life for material, and his belief that what made his fiction successful was something literal about its truthfulness.

In spite of these legal concerns, Updike, for nearly the first half of his career, was generally free to write about whatever and whomever he wished. That changed in the mid-1970s when he separated from Mary, took an apartment in Boston’s Back Bay, and developed a relationship with Martha Bernhard, who would eventually become his second wife. In a letter to Mary of May 27, 1976, he explains of his story, “Killing,” recently submitted to Playboy: “I don’t think they’ll take it . . . but do you concur with me that the story, though intimate (indeed, it is about intimacy, if I could write it right), betrays no secrets, offends no children, etc.” When Mary objects, he is forced to pull the piece, which Playboy had already accepted and paid for. On December 16 of that same year, he publishes a story, “Domestic Life in America,” in The New Yorker, that draws a strong response from Alex Bernhard, Martha’s first husband. In a registered letter sent to The New Yorker, Bernhard, a Boston attorney, suggests the possibility of legal recourse if the magazine publishes another Updike story that invades his, or his children’s, privacy. Thereafter, Updike avoids writing explicitly about his stepchildren, with whom he was then living. Though never at a loss for material, he must have chafed at being

constrained in such a manner. Neither Mary nor his parents had ever stood in the way of his earlier work, and while it could not have been easy for Mary to see their unraveling marriage chronicled fictionally in The New Yorker, she had always been helpful to and supportive of his writing. Updike greatly valued her input as a reader, though as he explained in a letter, written just prior to their separation, “What you must realize is that once I begin a story you become a character, not a person; Monet’s haystacks didn’t complain that they weren’t really purple. A person is much better than a character in every respect except that he or she doesn’t fit into a story.”

The other issue that crops up early in his letters is concern over obscenity and sexuality. While Updike’s New Yorker stories were written so as to not challenge the magazine’s somewhat prudish conventions at the time, his novels were a different matter. Rabbit, Run (1960) included muted description of sexual acts, including fellatio. In addition, it deals with a character who generates considerable domestic chaos and is never truly punished for his actions. In December 1959, Updike sent the manuscript to his good friend Goldy Sherrill, rector of Ascension Memorial Church in Ipswich, after Mary expressed concerns as to whether Sherrill would be upset by his depiction of the novel’s minister, Jack Eccles. In his letter to the rector, Updike writes, “He doesn’t look like you, act much like you, play golf like you, have a wife or a parish like you”; however, he adds, “I know for a fact . . . that home-town folks . . . do read with an overavid eye for real-life counterparts.” While Sherrill did not object to Updike’s depiction of Reverend Eccles, he expressed such strong reservations and disappointment with the novel’s immorality that Updike, then vacationing in Anguilla, sent him two more letters attempting to explain himself: “I am uneasy in the robes of a would-be prophet and pornographer—it offends all my social instincts, against which I wage a constant battle. The Rabbit in me is a furtive creature who is easily scared, and who was given a nasty start by your wrathful letter.” He goes on to say, “I had not intended to reply at all . . . But I kept hearing your disappointed voice plucking at my side, and the vision of you joining my mother, my father, my wife, and the other dear friends who wonder why in my writing I am so ugly, so brutal, so unsympathetic, so un understanding, was too much to bear in silence.”

Several months later, Alfred Knopf has two of his lawyers read the manuscript of Rabbit, Run, then asks Updike to come to New York, where they can all sit down together and examine passages. Over the ensuing days, this leads to uncertainty about the novel’s future: Will it be published? Will offensive passages be edited, or replaced with asterisks? Could the author and publisher could go to jail? Eventually Updike makes changes to the text, and it is published to considerable attention and acclaim. Curiously, at the

same moment Rabbit, Run is being scrubbed of obscenities, Updike, as he explains in a letter to his parents, is teaching summer Bible school at his Ipswich church. A few months later he receives a missive from his motherin-law, Elizabeth Pennington, voicing her strong disapproval of the novel. His response, of October 27, 1960, is characteristically diplomatic. Thanking her for her letter, he writes, “Your reaction to Rabbit, while somewhat severe, is not inappropriate,” and explains that “trying to tell the truth is not really a welcome service, but I haven’t figured out any other way to go about my business.” Before ending his letter with the send-off “Love, Johnny,” he writes, “I’m sorry that through the accident of marriage you have been thrown into close familial conjunction with a writer you don’t really like; honestly, I don’t ask you to read me. I send you the books as a token of my esteem and affection.” What these exchanges reveal is the extent to which Updike, as a young writer, was under pressure, arousing considerable disapprobation from family and friends, leading him to explain in a 1960 letter to Sherrill, “I feel, in writing [Rabbit, Run], that I was working against the grain, although some scenes felt good. But if you are ever going to improve you must keep biting off more than maybe you can chew; otherwise, the bites get smaller and smaller and eventually all you have left is the taste of your own saliva.”

Updike of course was also working against the grain, drawing the censure of others, when he separated from Mary in 1974 and then, in 1977, married Martha. His letters to the two women during this turbulent period are memorable as well as strikingly dissimilar. Those to Martha, as they begin their affair in January 1974, are vibrant and intensely erotic, spilling over with joy and pleasure. Upon receiving a letter from her while in Australia, he immediately responds: “I walked down King William Road laughing out loud and had I been a rooster I would have crowed.” Feeling newly liberated by their affair, Updike writes to Martha several times a week that first year, extolling her virtues, celebrating their intimacy, and imagining a future together. At the same time, his letters to Mary, composed in a sadder key, are practical, patient, and thoughtful, as he seeks to mitigate the pain of their separation. Though it’s Updike who wishes to end the marriage, he strives to ensure that his wife and children, in spite of the distress he causes them, will be all right. The letters written to both women from 1974 to 1977 are among his most compelling, and collectively they chronicle his passage through one of several marital crises. The letters from this period reveal Updike navigating domestic turmoil, trying to reimagine his life amid painful circumstances. They also mark the end of his time in Ipswich, where he and Mary had been socially active, immersed in a “swim” of other couples, and where, he confesses, he had become “greedy for my quota of life’s pleasures.”

Following his divorce and remarriage, Updike’s domestic life calmed, leading to far fewer letters to both Mary and Martha. Although he continues to write to his mother until her death, the increasing ease of telephone contact made those letters less frequent. Thus, his letters from the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s are weighted more toward the professional. Many are to fellow writers. Updike is generous with praise not only to younger authors he admires, such as Nicholson Baker and Adam Gopnik, but to contemporaries like Donald Barthelme, as seen in this 1986 letter: “Thank you for the gift of Paradise . . . What sticks in my mind is the linoleum knife one of the girl’s boyfriends used on her, and the details of his having a skin cancer on his forehead removed, and the ‘hooking’ gesture one of the heroines uses in the moment of supreme intimacy . . . As usual, you make the rest of us look as though we’re shadow-boxing, or being nice nellies.” Updike can also be selfdeprecatingly funny, as in this 2005 letter to Ian McEwan: “It occurs to me that since you interviewed me that first time in a BBC studio you have risen to be generally called the best novelist of your generation whereas I have fallen to the status of an elderly duffer whose tales of suburban American sex are hopelessly yawnworthy period pieces.”

Among his late professional correspondence are letters pertaining to two ambitious, end-of-the-century editing projects Updike undertook: A Century of Arts and Letters (1998) and The Best American Short Stories of the Century (1999). In spearheading the former volume, which offers a history of the American Academy of Arts and Letters,* he solicited, guided, then edited the contributions of ten prominent aging writers, including Norman Mailer, Cynthia Ozick, and Arthur Schlesinger Jr. In a veritable comedy of correspondence, Updike is continually prompting his famous contributors to meet deadlines and respect contracts; when a problematic draft arrives on his desk, he must cajole the author with a mix of flattery and critical counsel. As he explains to an editor at Columbia University Press during an episode that threatened the project, “I’ll try to keep my unruly herd of immortals more in line, though it’s not easy.” While the work he did in these volumes is exemplary and a service to American literature, the question arises as to

* Located in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Upper Manhattan, the American Academy of Arts and Letters is a three-hundred-member honor society of artists, architects, composers, and writers committed to fostering the arts. The naming history of the institution is complicated. Established in 1898 as the National Institute of Arts and Letters, the organization was originally capped at two hundred and fifty members. In 1904, they established the American Academy of Arts and Letters, a prestigious inner body of fifty additional members, who could be elected only after having already been a member of the larger National Institute. Updike was elected to the National Institute in 1964 and the American Academy in 1976. The bicameral system of membership was phased out in 1993, with the National Institute dissolving and all members of both organizations becoming members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. The academy annually distributes awards, funds concerts and events, and hosts gatherings of its members.

Why? Why take on these tasks, which consumed considerable time and energy? Clearly, he enjoyed the editorial work, which kept him busy and productive during a period in which, his children and stepchildren grown and his personal life stable, he had more available time. In addition, by overseeing two retrospective projects late in his career, both of which sought to chronicle achievement in American literature and art during the twentieth century, he was able to shape the historical record to his tastes and perspective. Though he did not seek out these projects, they allowed him to preside as a literary arbiter of the writing and artistic history of his time, with the work contributing to his stature and legacy.

While Updike in his later years acknowledges that he is no longer at the vital center of his culture, and that his literary stature has diminished, his final letters and books reveal that he never slowed down. When he died in January 2009, Updike was actively working on five books, four of which were in production, the other his never-to-be-completed novel on the life of St. Paul. In between hospital visits to battle stage 4 lung cancer, he would write poems, read proofs, and compose farewell letters. In the final weeks of his life, when his health had greatly declined, he explained to a friend, Dick Purinton, that he could no longer write, and how devastating that was. Yet, as we see in the penultimate letter in this volume, concerning proofs of The Maples Stories, he was attempting until the end to find the right words.

HOW THESE LETTERS will alter our view of Updike is not clear. Some readers will be moved by, and wish to explore further, his unique and fluent correspondence with his mother. The thousands of letters the two exchanged will likely play a role in future Updike studies. Other readers may begin to question certain currently prevailing attitudes toward the author. For instance, a few critics, late in his career, labeled Updike a narcissist, lumping him together in this regard with Roth, Mailer, and Saul Bellow. However, the characteristics of a narcissist—grandiose self-importance, need for excessive admiration, sense of entitlement, lack of empathy, arrogance, and haughty behavior—don’t describe the author of the letters in this volume. Updike frequently sent notes of praise to fellow writers; he was diligent and generous in answering reader mail, sometimes even providing comments on unsolicited stories sent by strangers; he was attentive to his mother and continually shared news about his children; he was unusually modest and viewed himself as immensely fortunate in all that life had bestowed upon him. Further, his letters were largely written, as mentioned, to give pleasure, both to himself and others. Narcissism seems a term applicable only in the sense, perhaps, that all writers and artists are self-involved.

Readers will find much to admire in Updike’s letters: comic genius, glorious sentences, a remarkable ability to compartmentalize (in navigating the emotional chaos of a marital crisis and adulterous affair, he could still complete his writing and attend to family demands and chores). Yet it’s not entirely clear how much Updike valued them. Though these communications were an important part of his daily routine, he made no effort to preserve copies of his outgoing correspondence. Further, in 1970, he referred to his letters, in typical self-effacing fashion, as being “among the dullest perhaps in the world,” very unlike Vladimir Nabokov’s, which he called “fascinating.” While reviewing the letters of James Joyce, he remarked in a letter to Maxwell, “Mine suffer by the comparison. Until I can make jokes in Italian to you, and address the mayor of Zurich in German, I won’t be half a man.” Funny and self-mocking, the comment also reveals his familiar false modesty, as if secretly he is pleased to be a regular guy, one who cannot joke in Italian. Yet Updike’s letters are hardly dull, and they are funnier than those of Nabokov or Joyce. Perhaps a more clarifying remark comes in another letter to Maxwell, after a journalist has requested access to their correspondence: “All of us, had we known our mail would be investigated, would have written less freely as we worked away.” Although partly disingenuous—Updike was aware that his letters would be collected and published—there is truth in his having written freely, which is what makes the letters so appealing.

That said, readers who in the past have not been engaged by Updike may find reasons for resisting once more. Some may regard his thinking and language, whether on sexuality, gender, or sexual orientation, to be oldfashioned, problematic, even offensive. Others may view him as yet another privileged white male, the essence of American whiteness, who was overly concerned with himself and little interested in the world beyond (his reading and book reviews, on authors from six continents, would suggest otherwise). In addition, Updike’s life, as reflected in his letters, is clearly not as dramatic or as adventurous as that of, say, Ernest Hemingway or Mailer, nor as committed to social justice as that of James Baldwin or Toni Morrison. Updike instead followed Flaubert’s advice of adhering to the conventions of a bourgeois life so as to be creative and original in his work; as such, the middle-class mundane became the subject of not only his fiction but also his letters. What he accomplished with the quotidian resembles what Thoreau achieved in writing about Walden Pond and nature—that is, through watchfulness, precise description, and intelligent, eloquent prose, Updike was able to bestow vibrancy and meaning upon that which would otherwise seem ordinary, so that it resonates and hums. In so doing, he offers us a new way of seeing and knowing our daily lives. Though not grand in the way of American skyscrapers and national parks, Updike’s letters, in their under-

stated, comic fashion, nevertheless chronicle a grand American success story, in which the bookish adolescent from Plowville, armed with literary talent, a typewriter, and postage stamps, journeys from an unheated sandstone farmhouse to become one of the world’s major literary figures. While writers will continue—through emails and texts, blogs and direct messages, tweets and podcasts—to communicate with the world, it seems unlikely that America will produce another letter writer as adept and as prolific at the form as John Updike.

Note on the Text

GIVEN THAT UPDIKE was both meticulous and frank in his writing, every attempt has been made to preserve his letters as written. There is no censorship, no expunged passages.

Updike’s correspondence, though often typed quickly, was generally clear and correct, with few misspellings and punctuation errors, though minor ones crop up in most letters. Silent edits were made here to correct typos and misspellings. When the misspelling appears intentionally quirky or archaic (“razzberry,” “stomache,” “literatchoor”), or adheres to a preference for, say, the New Yorker style book (the doubling of consonants in words like “unravelled” and “marvellous”), it remains as written. Punctuation also remains largely as written; however, in the case of a clear omission (a missing period) or conspicuous error (a comma that makes no sense), an edit was made. In addition, I looked for overall patterns in Updike’s letter writing regarding his use of commas, and added them whenever appropriate. That said, I was cautious about overstepping, so resisted altering the text unless relatively certain. As letters, these compositions have a more hurried quality than Updike’s writing in other genres, with fewer pauses, and I wished for that to remain. In addition, trying to insert punctuation according to what I thought Updike would do felt like an impossible task, so I refrained, except when a passage would otherwise be confusing. On rare occasions, a sentence or phrase may appear odd in its syntax, grammar, or punctuation; if an obvious and simple solution was not apparent, the sentence remains as written. In cases where a word was added (usually a preposition) or a verb tense was altered, it is usually not noted. However, if the fix was less obvious, the added word appears in brackets. The titles of literary works (novels, short stories, poems) and films, which in some early letters were either underlined, written in caps, or not marked, have been standardized through either italics or quotation marks.

Updike’s language and thinking clearly reflect the time in which he wrote. Words, phrases, and attitudes, particularly related to gender and race, that were more commonplace in 1955 or 1986, may seem problematic today, even offensive. Because Updike was so candid in his fiction writing, the option of censoring words or passages in his letters seemed inherently wrong. Thus, the letters stand as written, with the acknowledgment that some terms and passages will prove vexing or unsettling.

While almost all of Updike’s letters are signed, some, particularly from his papers at Houghton Library, bear no signature. By and large, these are photocopies, or an extra copy from Updike’s printer, of letters that were subsequently, perhaps minutes later, signed and mailed. Martha Updike would sometimes make photocopies of what she thought were her husband’s more interesting letters. While the original was presumably signed before being placed in an envelope, the copy was typically made before the signature occurred. In these instances, Updike’s name, depending on his relationship to the recipient, is inserted as either “John” or “John Updike.” In a few personal letters, Updike does not close by signing his name, and in such instances, his name was not inserted. The positioning on the page of the closing phrase and signature varies greatly from one letter to the next, but here they are standardized and positioned on the far-right side of the page.

While Updike generally provided the day and month whenever writing a letter, he seldom included the year and almost never indicated the place or address from where he was writing. In nearly every instance, the precise year and his location could be determined through research, and so both have been inserted to standardize the headings, though they do not typically reflect the original (e.g., while Updike may have only written “March 2,” the letter is recorded here as “Lowell House E-51, Harvard College / March 2, 1950”). In a few instances, it was unclear as to whether a letter was composed in, say, 1974 or 1975, and in such cases, the year that made best sense was used, followed by a question mark.

Though Updike sometimes composed letters that stretched to two or three pages, he was mostly committed to the one-page, typed letter or postcard. When he had more to say but wished to confine himself to that single page, he would, perhaps two-thirds of the way down, reduce his line spacing so as to squeeze in more words. If he arrived at the bottom of the page and still had another sentence or two in mind, he would typically scroll back to the top and type his final sentences above the date and salutation.

Though an effort was made to locate the original version of all letters included in this volume, in various instances I found only a copy. While it seems likely the copy is identical or nearly identical to the original, such a determination cannot be certain.

Footnotes are offered to illuminate names, events, comments, and phrases in Updike’s letters that would otherwise be unclear. In some instances, these notes provide context, including, when available, direct quotation from the other side of the correspondence. This practice is most visible in his letters to his mother; given her importance, I felt the reader should hear her voice. Though an effort was made to keep footnotes to a minimum, so as not to interfere with the reading experience, the pressure to annotate was felt as a steady counterforce. And because Updike was highly attentive to the quotidian, minor details, at times, cried out for explanation. For those interested in going further, many unexplained names, events, and references can be googled. Other references, however, withstood my detective work and remain, alas, mysterious.

A Life in Letters

Dear Pop,

To W ESLEY U PDIKE , father

117 Philadelphia Avenue, Shillington, PA

June 3, 1941

I hope you’re feeling fine.* If you aren’t I feel sorry for you. I wish you hadn’t got that rupture. Cause, if you didn’t have it, you wouldn’t be where you are now. I’ll be glad when you are back home. How much do matches cost.† When I come to visit you on Sunday. . . . oh, skip it! Everything is fine back home. (I think.)

Yours truly, Your son, Who loves you very much, John Hoyer Updike (Johnny to you)

* Wesley Updike was at the U.S. Naval Hospital in Philadelphia for a hernia operation; his stay lasted three weeks. In an accompanying letter, Updike’s mother writes: “Johnny says everything he is writing to you sounds hollow. But that’s because we are hollow when you are away.”

† David Updike, John’s older son, views the matches as “a sly reference to smoking, and the hint that he will smuggle some matches into the hospital so that his ailing father can have a cigarette.”

To T HE E DITORS OF E LLERY Q UEEN ’ S M YSTERY M AGAZINE

Plowville, PA*

June 7 [1947?]

Sirs:

A copy of To the Queen’s Taste has found its way into my library and from there into my hands. I was impressed and surprised to find in it mystery stories by such writers as Marc Connelly, MacKinlay Kantor, Wilbur Steele, Jim Hilton, and Somerset Maugham, all of whom have made their reputations in other fields of literary endeavor.

James Thurber, one of the best of American humorists, wrote a very unfunny and rather terrifying story called “The Whip-Poor-Will,” a story that might very easily be used in your magazine. It appears in the book My World—And Welcome to It, published by Harcourt, Brace, and Company in 1944.

I hope that you will find time to look into it, for the story, in my opinion, would stand out anywhere, even in the company of the best available mystery writers.

Sincerely, John Updike R. D. #2

Elverson, Pa.†

Dear Mr. Caniff:

To M ILTON C ANIFF , American cartoonist

Plowville, PA September 6, 1947

For a long time, I was under the impression that Terry and the Pirates was the best comic strip in the United States. Imagine my dismay, then, when I heard that its creator, its mastermind, was going to desert Terry, leave it in the lurch, and wander off to some new interest, called Steve Canyon. Apprehensively I subscribed to the paper that carried Steve Canyon and waited for

* Updike moved, with his parents and maternal grandparents, from Shillington to Plowville on Halloween 1945. Though their house and farm were located in the unincorporated area of Plowville, the postal service recognized the borough of Elverson, seven miles south, as the official address.

† Until he left for college, Updike would close his letters in this manner, listing his address after his signature. Decades later, he would frequently use a blue ink rubber stamp to record his return address at the close of a letter. The address has been omitted in subsequent letters.

results. It didn’t take me long to discover that Steve Canyon was now the best comic strip in the United States. Obvious conclusion: Milton Caniff is the best cartoonist in the world.

I have never before expressed my appreciation to you for your work, but I feel that now is the time. I and my family are trying to make the upstairs look decent, and I am trying to find something to cover a blank wall in my bedroom. What, I reasoned, would be better than a sketch by my favorite cartoonist. This brings me to the point of my letter. Would you be kind enough to supply me with an original comic strip, or a sketch of Steve, or anything you would care to give me? I realize that you must be very busy, but any attention you pay me will be greatly appreciated. I promise that whatever you send me will be elegantly framed, hung, and treasured for a long, long time.

Sincerely,

John Updike

To H AROLD G RAY , American cartoonist

Plowville, PA

January 2, 1948

Dear Mr. Gray,

I don’t suppose that I am being original when I admit that Orphan Annie is, and has been for a long time, my favorite comic strip. There are many millions like me. The appeal of your comic strip is an American phenomenon that has affected the public for many years, and will, I hope, continue to do so for many more.

I admire the magnificent plotting of Annie’s adventures. They are just as adventure strips should be—fast moving, slightly macabre (witness Mr. Am), occasionally humorous, and above all, they show a great deal of the viciousness of human nature. I am very fond of the gossip-in-the-street scenes you frequently use. Contrary to comic-strip tradition, the people are not pleasantly benign, but gossiping, sadistic, and stupid, which is just as it really is. Your villains are completely black and Annie and crew are practically perfect, which is as it should be. To me there is nothing more annoying in a strip than to be in the dark as to who is the hero and who the villain. I like the methods in which you polish off your evil-doers. One of my happiest moments was spent in gloating over some hideous child (I forget his name) who had been annoying Annie [and then] toppled into the wet cement of a dam being constructed. I hate your villains to the point where I could rip

them from the paper. No other strip arouses me so. For instance, I thought Mumbles was cute.*

Your draughtsmanship is beyond reproach. The drawing is simple and clear, but extremely effective. You could tell just by looking at the faces who is the trouble maker and who isn’t, without any dialogue. The facial features, the big, blunt fingered hands, the way you handle light and shadows are all excellently done. Even the talk balloons are good, the lettering small and clean, the margins wide, and the connection between the speaker and his remark wiggles a little, all of which, to my eye, is as artistic as you can get.

All this well-deserved praise is leading up to something, of course, and the catch is a rather big favor I want you to do for me. I need a picture to alleviate the blankness of one of my bedroom walls, and there is nothing that I would like better than a little memento of the comic strip I have followed closely for over a decade. So—could you possibly send me a little autographed sketch of Annie that you have done yourself? I realize that you probably have some printed cards you send to people like me, but could you maybe do just a quick sketch by yourself? Nothing fancy, just what you have done yourself. If you cannot do this (and I really wouldn’t blame you) will you send me anything you like, perhaps an original comic strip? Whatever I get will be appreciated, framed, and hung.

Sincerely,

John Updike

Plowville, PA

March 21, 1949

Gentlemen:

I would like some information on those little filler drawings you publish, and, I presume, buy. What size should they be? Mounted or not? Are there any preferences as to subject matter, weight of cardboard, and technique?

I will appreciate any information you give me, for I would like to try my hand at it.†

Sincerely,

John Updike

* Mumbles, a recurring villain in Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy, made his debut in that comic strip in October 1947.

† At age thirteen, Updike began submitting poems, drawings, and other unsolicited pieces to various magazines, including The New Yorker. Few of these cover letters have survived.

To T HE E DITORS OF T HE N EW Y ORKER

To T HE U.S. D EPARTMENT OF THE A RMY /P ENTAGON

Plowville, PA March 27, 1949

Gentlemen:

I am hoping that this request, however vaguely addressed, will eventually find itself in the hands of the men who can supply me with some information and statistics on The Pentagon.

A rather playful geometry teacher of mine has assigned as a class project the preparation of a booklet on the construction of any building. So any pictures, booklets, etc., will be sincerely appreciated. I realize that this might cost, so just let me know and I will be glad to send you the amount required.

I am rather late in getting this letter off, so I would doubly appreciate prompt reply.

Sincerely, John Updike

To E ARL B. M ILLIETTE , director of the division of fine and industrial arts, Philadelphia Public Schools

Plowville, PA April 4, 1949

Dear Mr. Milliette:

Your interest in my work has made me, and Mr. Boyer,* very happy. Having heard that cartoonists bring about one dime per dozen on the market, my enthusiasm does not pile up. Last year’s award, however, helped me to believe that I might reach The New Yorker before I’m too old to enjoy it.

We appreciate your choice of a cartoon for the Pittsburgh exhibition. One of my boosters thinks it is the best thing I’ve done. But, with Mr. Boyer’s help and your encouragement, we may be able to send you something really spectacular next year. Until then, we thank you for the kind words and wish Harold Ross† were more sympathetic.

Sincerely, John Updike

* Carlton F. Boyer was Updike’s art teacher.

† Cofounder and editor in chief of The New Yorker.

To B ARNES & N OBLE , I NC ., New York booksellers Postcard

Plowville, PA June 15, 1949

Sirs:

Do you have available a copy of THE SEAL IN THE BEDROOM, by James Thurber, GOOD HUMOR MAN, by George Price, FELLOW CITIZENS, by Gluyas Williams, REJECTIONS, by Alan Dunn?*

If you have one or more of these, kindly hold them and notify me.

John Updike

To G ORDON W ILLIAMS , sports columnist of the Reading Times

Plowville, PA August 24, 1949

Dear Gord:

I think that the question aroused by the recently forfeited game† resolves itself not to pop bottles and tinhorn bettors but to the character of the Philadelphia baseball fan. One who has watched 30,000 of them tumble, snarling and snapping, from the ball park cannot help realizing that these are no ordinary fans, but a horde of vicious fault-finders who not only boo the visiting teams and the umpires but the home team as well. I have read several times that baseball umpires consider Philadelphia the worst town to umpire in the league, and each time I see a game I am amazed by the variety of things the Philadelphia rooter can boo.

He not only is annoyed by each visiting player, by the umpires, and by his own home team, but doesn’t seem to like the public announcements, the right field scoreboard, and the ground crew. The one thing that gives him

* All four books are collections of cartoons and drawings.

† The game between the Philadelphia Phillies and the New York Giants at Shibe Park on August 22, 1949, was forfeited by the Phillies after their fans, protesting a call, threw soda bottles and other objects onto the field, hitting several umpires.

pleasure is the sight of two or more middle-aged men fighting over a foul ball.

While I do not doubt the good intent of your column on Tuesday and the action of the Shibe Park officials in banning bottles, I believe that the fan will now fill his pockets with rocks, and, if that turns out to be impractical, will hurl himself on the field from the upper deck.

The solution is obvious. The Philadelphia games will have to be played on some isolated lot, high on a mountain or deep in the woods, safe from the fury of their fans, and a huge, damage-proof television screen installed in the field, at which the rooters can boo, hiss, and throw bottles to their heart’s content.

Sincerely,

John Updike

Updike’s letter was published, almost in its entirety, in Williams’s column, “In the Realm of Sports,” in the Reading Times on August 30, 1949. In a subsequent column that ran on September 9, 1949, a fan wrote to “disagree violently with Updike’s views, whether they were serious or not,” and offered his own suggestions.

To T HE E DITORS OF L IFE M AGAZINE

Plowville, PA August 29, 1949

Sirs:

I am surprised and dismayed that Life publishes the letters of cranks who think they are being both wise and witty when they compare an infant’s scrawlings or the dribblings on a garage door to the work of a sincere, unique painter like Jackson Pollock.*

John Updike

* Updike, at seventeen, was responding to several letters in the August 29, 1949, issue of Life that were prompted by an article of August 8, 1949: “Jackson Pollock: Is He the Greatest Living Painter in the United States?” One letter writer included a photograph of her son, “a 5½-year-old contemporary of the Pollock trend in art,” standing beside “his latest effort.” Another wrote: “I have an old garage door on which I have cleaned paint brushes for several years. It is rather similar to Pollock’s Number Seventeen. The first $1,500 takes it.”

To F. S. VON S TADE J R ., director of scholarships, Harvard College

Dear Mr. von Stade:

Plowville, PA

May 14, 1950

An award of five hundred dollars will make it possible for me to come to Harvard this year.* My parents and I are both grateful and pleased with the prospect. The reasons for wanting to graduate from Harvard are almost innumerable.

I am, however, one of several alternates on the national scholarship list of another school and believe that I should reduce my parents’ responsibility for my education to the greatest possible extent. Even without a personal acquaintance with my family and its financial difficulties, you must see how much the possibility of winning a national scholarship tempts me.

So, I hope there will be time for me to consider all sides of my really complex situation before the twenty-second of May. If necessary, may I withhold my decision until the end of the month?

With sincerest thanks for all the consideration you and Harvard alumni of Reading and Philadelphia have given to my problems, I am,

Sincerely yours,

John H. Updike

To R OBERT C. L EA J R ., Philadelphia attorney and Harvard alumnus who interviewed Updike in 1949 at the Harvard Club rooms at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel

Plowville, PA

May 24, 1950

Dear Mr. Lea:

Perhaps you already know (if you don’t, you will as soon as you complete this sentence) that I am going to Harvard.†

Now that all is over but going to the school, I should like to thank your committee for the time, consideration, and food they gave me, and thank you especially for your enthralling talks on Harvard, for the discussion we

* Updike has been accepted to both Harvard and Cornell, and rejected by Princeton.

† Though awarded the national scholarship to Cornell, Updike in the end chose Harvard, where he received a tuition scholarship.

had on that amazing magazine, The New Yorker, and for making me a lot less frightened about the who business of college.*

I hope I will not disappoint you; at any rate, I will keep you informed of my progress or regress at Harvard University.

Gratefully yours, John Updike

To C HARLES “J ACK ” H EMMIG , supervising principal of Shillington High School

Dear Mr. Hemmig:

Plowville, PA

August 7, 1950

In a way, my commencement speech† was an attempt to explain what you have called the enigma of my class. Realizing our need for maturity and freedom, we may have been over-zealous. But we are at the crossroads and the signposts are not easy to read. We wanted understanding and sympathy without knowing how to get it. We are, in short, on the verge of maturity and I, personally, believe my class has what it takes.

If you agree with me in this belief, is it not possible that a questionnaire‡ at this time might tend to destroy the satisfaction we feel in our graduation from the Shillington High School? We are grateful for the tolerance we enjoyed there and believe that we are adequately prepared to continue our educations wherever we go. So that a questionnaire might easily be more destructive than helpful. Of course that is only my answer to your question. I am not very well informed in the uses of questionnaires. You may find one very useful.

I thank you for the many happy privileges that I shared with my classmates at Shillington High, for your kind letter of August third, and all the encouragement you and my teachers have given me during the last twelve years.

Sincerely yours,

John H. Updike

* Though “whole business” would seem more likely and appropriate than “who business,” the latter is what he wrote, and given his clever opening, it seems possible that Lea had talked to Updike about the people of Harvard College.

† Updike was co-valedictorian of his class and delivered a commencement address on May 29, 1950.

‡ In a letter of August 3, 1950, Hemmig thanked Updike for the copy of his commencement speech and expressed a desire “to know in what respects the school failed” Updike’s class and whether a survey of seniors could be useful.

Mrs. Lewis:

To T HELMA L EWIS , teacher of English and German at Shillington High School and faculty adviser to the student newspaper Chatterbox

Plowville, PA September 5, 1950

Much (or is it many) thanks for the Songs of Youth. * My mother, who never did understand my apathy toward the American Poetry Society, was delighted at your kindness, and even I was once again stirred by the sight of my work in print.

It is indeed an interesting book. Perhaps the most interesting thing about it is the clever way the publishers, with the low cunning characteristic of those who print my stuff, obscured the entire point of my poem. By some exclusive process, they have hollowed out each punctuation mark until it is but a shadow of its former self. Since my little effort is dependent on the punctuation used, I suffer a good bit. The spacing is ingenious, too; it gives to the printed page the quality of a conversation between a chronic stutterer and a man trying to talk and remove bits of celery from between his teeth simultaneously.

I wonder how they did it. FM† was up here and saw it, but his inherent fastidiousness prevented him from commenting at length. For a second, however, I saw flicker across his face the expression characteristic of him before he got religion.

My father tells me you wish to see me before I depart for the second biggest atomic bomb target north of Wilmington. I am now in bed with a sinister combination of asthma, nasal congestion, and Updike’s Botch. As soon as I can prevail over my afflictions, I will hustle in to the Alma Mater (Latin for No Spitting, Please, Under Penalty of Fine And Prosecution).

Thank you once more for the surprising and welcome gift.

J. U.

* Updike’s poem, “Move Over, Dodo,” first published in Chatterbox in spring 1950, has been reprinted, with Lewis’s assistance, in an annual publication, Songs of Youth, by the American Poetry Society.

† Fred Muth, high school classmate and co-valedictorian who had been a close friend since first grade.

To B ENNETT C ERF , cofounder of Random House publishers

Plowville, PA

September 7, 1950

Dear Sir:

When, oh when, will Random House throw the palpitating public another New Yorker cartoon album? Nearly a decade has passed since the appearance of The New Yorker War Album, many changes have taken place. The two proponents of the captionless gag and the subtle series, Claude and Cobean, have become powers to be reckoned with.* The rise and fall of C. E. Martin occurred in the eight-year interval. Anatol Kovarsky zoomed out of nowhere to challenge Steinberg, and fail. Helen Hokinson has died; Mischa Richter has departed to the green fields of syndication; Richard Taylor has faded. Robert Day has switched from wash to a sloppy pen line. Newcomers like F. B. Modell and Dana Fradon flicker briefly. And all the time you twiddle your tomes, recording nothing of this.

Or look at the specialized anthologies. After Carl Rose, what? A book devoted to the superb wash work of Richard Decker or the skilled pen of Daniel Alain? No indeed, another one by Charles Addams. I might be shoving my neck out on this, perhaps Decker and Alain have been done by someone else. I am aware that Price (George and Garrett), Day (Chon), Hokinson, Steinberg, Arno, Dunn, Steig, Hoff, Rea, and (I think) Williams have fallen into the hands of lesser houses than yours, but that still leaves the two old stalwarts mentioned above, as well as the newer Claude Smith and Sam Cobean.

It has been some time since the public has been treated to a cartoon anthology. I have been told that they were (and possibly, still are) considered a drudge on the market. Yet the best of anything will always sell. Arno’s Sizzling Platter is almost impossible to get today. The New Yorker has achieved a new stature in these last eight years. People who once dismissed it as an adult comic book now respect its mature and well-thought-out editorials, its fine, impartial news coverage, its tempered criticism, its contribution to the prose arts, and the fact that its cartoons are a painless commentary and an ingenious analysis. I know little about the publicational world, but I feel that at this time, an anthology of the best cartoons in the world, in an attractive book, with (and this is important) a fetching dust jacket, should sell.

You can be sure, at any rate, that I’ll buy it.

Sincerely,

John Updike

* Claude Smith and Sam Cobean, cartoonists known for their work in The New Yorker. The many subsequent names mentioned in this letter were also New Yorker cartoonists.

First letter sent home from college, September 25, 1950

To P LOWVILLE *

11 Hollis Hall, Harvard College September 25, 1950

Dear Mother, Father, Grandpa, Grandma, Chipper, Jolson, and all the ships at sea:

Harvard is a difficult place in which to write a letter. It would seem that the number of students in Hollis Hall greatly outnumbers the number of rooms; in fact, the overflow seems to be all in my room. I cannot explain why this is, my roommate† surely does all he can to discourage callers, a novel attitude that most of them find strangely alluring. I will try not to dwell on my roommate at unbearable length, but perhaps you might be interested. He, too, writes, although not terribly much. He has the nagging feeling that nothing he will write is good enough, and, consequently, rather than put down an inept word, he plays tennis. He claims he wants to be a writer, but, in the short time I’ve been here, he has done nothing about it. This does not indicate, to him, at least, any inferiority to me, a mass producer. In fact, it seems to be a mark of fastidiousness that I lack.

Moody would be a kindly adjective; nasty might be better. Not that I dislike him. His faults are a pleasant complement to mine, although perhaps the pairing up of two writers might be as interesting an experiment as rubbing two tomcats together. His posture, for instance, is even worse than mine, and he is even sloppier than I (honest). I wish that he had brought along some of his work. He says it stinks, and I would be very grateful for some confirmation. At any rate, he has dismissed my work with an unconscious sneer, and has persistently prevented me from getting any work done.

He is surely charming, but no less so than the majority of the people here. I am rather frightened by the immensity of intelligence and variety of talents displayed here. It would not, I fear, be interesting reading to enumerate all my comrades and their charms. One is a Negro who reads Greek and Latin for pleasure, as well as Hamlet six times a year. Another is a big, intense Maine boy with one of the most remarkable voices I have ever heard.

Wood is here. He came up to me the other day in the Union, and he seemed as imperturbable as ever. In this vast lump of intellect, however, he didn’t look very impressive.

I sat down the other day to write you a letter, but I was so uneasy that the

* Updike employed various salutations in letters to his mother, father, maternal grandparents, and family pets (Chipper, Jolson—both dogs), who all resided in the sandstone farmhouse, on eighty acres, in Plowville, Pennsylvania.

† Robert Christopher “Kit” Lasch, a midwesterner (born in Omaha, Nebraska, and raised in a Chicago suburb) and the son of progressive intellectual parents.

words were hopelessly confused. I feel much better now. The boys of Hollis, a very sharp bunch, seem also friendly and gay. Whether they will be gay while this poet is trying to study, is unknown.

There are three people here besides myself, all of them talking. This letter is a difficult thing, as I had anticipated. There is little to say but that I am happy, and see no reason why I shall stop being. I am no longer scared, and I was homesick only after you left. I was glad to get your letter, though it took a long time to get from the hotel to the dorm.* My correct address is

John Updike

Hollis Hall 11 Harvard College Cambridge 38, I11.

Write soon, and forward my mail, I have gotten none.

Johnny

To P LOWVILLE

11 Hollis Hall, Harvard College Monday night [October 2, 1950]

Dear Mother, family, and Mrs. Benedict:†

Each day your letter finds a pleased, if disturbed, reader. I am at that stage when correspondence, hitherto only a medium of conversation with Bennett Cerf, has become an essential, as well as time-consuming, activity. It is difficult to imagine homesickness when one is home; now the prospect of three months in this cathedral to the rounded man is most unpleasant. The college itself has done nothing wrong; I am delighted by the way the Yard looks on a sunny day, and the way the front of Widener Library lights up at night. I revel in the abundance of food, of independence, of thought. And things seem to go well. My qualms about calculus may be refuted; I may be able to concentrate on my old foe, Latin; perhaps I can conquer the bitter feeling that each awakening brings. Even today I passed the Step Test,‡ an ordeal

* Updike was accompanied to Harvard by his mother and his aunt. His mother’s first letter, of September 21, 1950, was written on stationery from the Commander, a hotel located on the edge of the Harvard campus.

† Mrs. Hazel V. Benedict handled insurance and accounting work for the Updikes. It is not clear why he addresses her in this salutation, though likely for comic effect. In addition, now that he is at Harvard, where there are more expenses, communication with Mrs. Benedict regarding family finances has increased.

‡ A cardiac stress test.

imposed upon each freshman; and a physical test that my husky comrades were confident I could not meet. (How little they know how much their doubt spurred me on.) I paraded my scabby belly,* and received not even raised eyebrows, but courtesy and a blood-chilling disregard of my affliction. Even tonight I was told that of five poems I typed and three cartoons I inked in Sunday night, the Lampoon† was considering printing one (possibly two) of the former, and one of the latter. I seemed to be the brightest prospect in sight, as least in my sight.

And yet each new day brings new terror: tomorrow I take my first swimming lesson, tomorrow I confer for the last time with the adviser on my schedule, tomorrow I must canvas for Lampoon subscriptions. I have yet to have a section meeting, an exam, a grade, any indication of what sort of student I am. It is unfair to Harvard and to you to be anything but delighted at this wonderful place; no one (but my roommate, who thinks things are rotten) could find serious fault with anything. On each side you find recreation, advice, comfort, beauty, thought, stimulation. The people are all too kind; the big city throbs nearby; we move, casual, sure, laughing in a sheltered little world whose only impositions are upon a parent’s pocketbook and a poet’s tender temperament.

The week ago you mentioned seems like a month, the months ahead look like years. I am scared; and the most frightening thing is I have nothing to fear. I once said that I enjoyed beginnings and hated endings; I feel now that I don’t like either. I am liked, admired for my few talents (and how big they looked in Shillington); thus far I am a success. But the entire thing is too blank, too huge, to look forward to. (Pardon the construction; I’m tired.)

As to elbow rubbing: my time is so fully consumed by my worries and my studies that I have no urge to speak to anyone. I miss my ladies of Shillington; as yet, I seek no substitutes. Your son is much more passive than you would imagine.